Abstract

Background:

Comorbidity in bipolar disorder (BP) is common, of which anxiety disorder (AD) comorbidity has received recent attention. The aim of the present study was to find the prevalence of (current and lifetime) ADs in BP I with recent episode mania, its effect on illness severity and its treatment implications. This is unlike the convention of associating “anxiety” with depression. Here, the hierarchical diagnostic criterion of the DSM IV-TR was suspended for heuristic purpose.

Materials and Methods:

Consecutively admitted 102 consenting in-patients of bipolar mania were evaluated on Young Mania Rating Scale, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, and Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety, at baseline and after 45 days. When the patient became cooperative, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia - the lifetime version interview AD section, was conducted. Protocol for management of current acute state was kept flexible and naturalistic. All treatment details, historical bipolar illness and socio-demographic variables were collected from case record file and unstructured interview with patient and caregiver.

Results:

High prevalence of lifetime (70.2 percent) and moderate levels of current (29.6 percent) comorbid ADs were found. Comorbid lifetime AD was associated with more severe BP course (more past depressive episodes (P<0.001), less inter-episode recovery (P<0.01), and poorer response to acute phase treatment). Comorbid AD group needed more number of mood stabilizers for acute management (P<0.05).

Conclusion:

Findings illustrate the importance of this comorbidity having implications for psychiatric diagnostic systems.

Keywords: Anxiety disorder comorbidity, bipolar disorder comorbidity, prevalence of anxiety disorders

INTRODUCTION

Among axis-I psychiatric disorders coexisting with bipolar disorder (BP), anxiety disorders (AD) hold a prominent place in line with their high co-occurrence.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10] Kraepelin[11] was among the first to include anxiety as a symptom of mania. A review reveals that the prevalence of all comorbid ADs in BP is as high as 79%.[4]

The prevalence rates of comorbid lifetime ADs have varied widely between studies, from 12.5[12] to 92.9%.[13,14] Despite conflicting results in prevalence and frequency order of individual ADs, most commonly observed comorbid ADs in BP are generalized AD, panic disorder, phobias and obsessive-compulsive disorder.[3,5,6,7,15,16] The presence of comorbid anxiety has importance in terms of BP severity, prognosis, and treatment.[8,4,17] This is even more complicated by the frequent presence of more than one AD comorbidity.[2,3,18] Considering these preliminary findings, anxiety as a correlate of response to BPs has not been well studied.[19] Moreover, studies have always given greater importance of anxiety in the depressive phase of BP.[1,10,12,17,20] The current comorbid AD rates have not been evaluated in the manic phase of BP.

The present study was undertaken with the aim to investigate the prevalence of ADs (panic, generalized anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and phobic disorders), both current and lifetime, in BP I with most recent episode mania, its effect on illness severity (defined in terms of age of onset, number and type of past episodes, number of hospitalizations, inter-episode functioning, severity of current episode) and their treatment implications. A hierarchy-free application of diagnostic criteria was used (suspending the hierarchical criteria of the DSM-IV-TR) for heuristic purpose. This strategy has proved fruitful in previous studies.[5,6,21,22]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Consecutively admitted 102 consenting in-patients of bipolar mania who were drug free (i.e., not taken any antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, antidepressants, or anxiolytics within the last 4 weeks and depot injections within the last 12 weeks), between the ages 18 to 60 years of either gender were evaluated on Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), and Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A), at baseline and after 45 days. At the end of the study, when the patient became co-operative, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-the lifetime version (SADS-L) interview AD section, was conducted. Patients with mixed/depressive episode, or other comorbid axis I (other than bipolar or anxiety) disorders or axis II disorders, or with mental retardation, chronic medical, or neurological illnesses or those treated with electro-convulsive therapy were excluded.

Concerning management the choice and dosing of mood stabilizers were left to the discretion of treating team. Additional medication allowed were injection and oral haloperidol to manage psychosis and acute excitement and injection promethazine and oral trihexyphenidyl for patients developing extrapyramidal symptoms. No ratings were done within 6 h of receiving injection promethazine. For patients who developed severe and limiting side effects to injection or oral haloperidol were changed to oral olanzapine. All treatment details were documented in the patient's case record files (which is part of a regular practice). Treatment allowed, in short, was kept as naturalistic as possible. All details of current and past treatment, historical bipolar illness, and socio-demographic variables were collected from case record file and unstructured interview with patient and caregiver. All ratings, interviews, and data collection were done by (a single rater) the author. The protocol for the study had undergone necessary ethical clearance from the institutional ethical board.

Directional working hypothesis guided the study, i.e., appreciable proportion was assumed to have comorbid ADs, suffering more severe form of bipolar illness, and would differ in terms of treatment required.

Descriptive statistics was used for summarizing socio-demographic and clinical data. Independent sample t-test (for continuous data) and Chi-squared test (for categorical data) were performed for comparison between groups of bipolar patients with and without, lifetime and current ADs. Due to the small sample size of the individual AD groups, they were not assessed separately.

RESULTS

Of the total sample 84 patients were included in the analysis. Eighteen patients were dropped either because they opted out of the study or were started on ECT. All the patients were in a psychotic episode of mania.

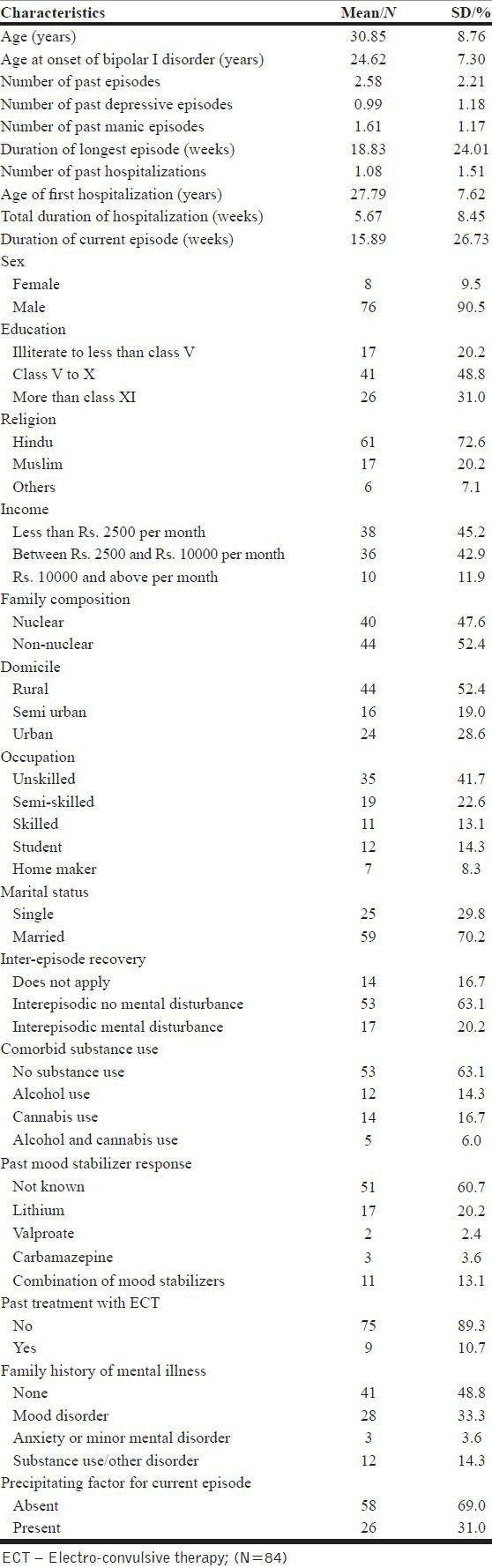

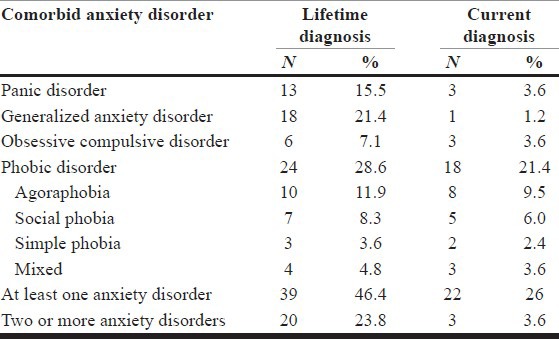

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic pattern of the sample. The prevalence of lifetime and current ADs are shown in Table 2. The most prevalent AD in bipolar I patients were phobic disorder (28.6% lifetime and 21.4% current).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

Table 2.

Prevalence of lifetime and current anxiety disorder in bipolar I patients

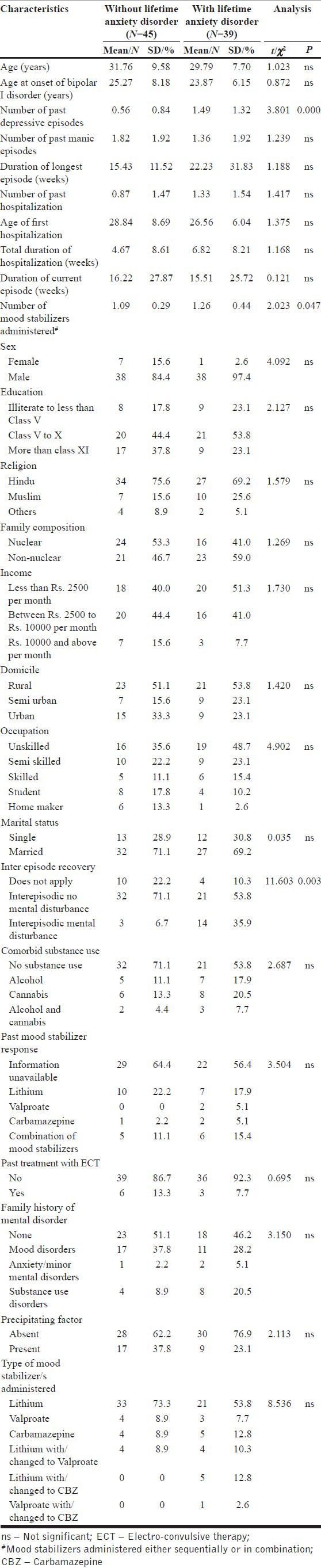

Table 3 shows the comparison of socio-demographic, past and current clinical, and treatment variables, family history of mental disorders between bipolar I patients with and without lifetime AD.

Table 3.

Comparison of demographic, historical illness and treatment variables in bipolar I patients with and without lifetime anxiety disorder

Though the group with lifetime ADs did not differ from those without lifetime ADs on socio-demographic variables, the former had significantly greater mean number of past depressive episodes (P<0.001), more persistent interepisodic mental disturbance (P<0.01), required more number of mood stabilizers (administered either sequentially or in combination) for current treatment (P<0.05).

In a similar analysis between groups of BP with and without current AD shows that patients with current AD had a significantly greater number of past depressive episodes (P<0.01) and past hospitalization (P<0.05) and had more interepisodic mental disturbance (P<0.05) as compared to bipolar patients without current AD. (Details are available on request to the corresponding author).

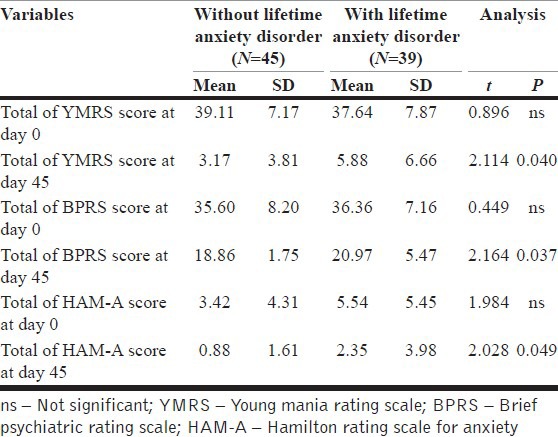

Comparison of ratings on YMRS, BPRS, and HAM-A between bipolar I patients with and without lifetime AD is summarized in Table 4. Though both the groups were similar at baseline, at day 45 the comorbid group had significantly more mean scores in all of the psychopathology scales.

Table 4.

Comparison of ratings on YMRS, BPRS and HAM-A rating scale in bipolar I patients with and without lifetime anxiety disorders

DISCUSSION

The study intended to evaluate ADs in 84 cases of bipolar I mania. Though many studies have linked anxiety with the depressive phase of the illness, the current study was the first to determine the prevalence of AD in bipolar population in the manic phase of illness. It excluded patients with comorbid diagnosis of substance dependence for two reasons: i) to exclude the potential confounds of substance induced AD, and ii) as previous related studies differed in its findings probably due to the difference in prevalence of comorbid substance use disorder in their sample.

The sociodemographic and the clinical characteristics of the sample were comparable to that of samples of other published studies from India (such as the age distribution of the sample,[23] marital status,[24,25] religious affiliation,[25] income status,[26] family set up,[24] prevalence of stress precipitating mood episodes,[27] and age of illness onset,[28,29,30] etc.). The apparent anomalous distribution of gender partly can be explained by the setting of the study site, i.e., inpatient of a mental hospital where admission rates are much lower in women than men, as evidenced from previous epidemiological research from the same site.[31]

The lifetime prevalence rates of ADs in our study were quite similar to the results of previous studies, reporting a high rate of lifetime ADs in BP I.[4,14,21] Some variation can be explained by the difference in methodology (e.g., inclusion of bipolar II group, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in the ADs). This high prevalence rate of comorbid ADs among bipolar I patients in their manic phase of illness indicate that the practice of assigning affective diagnosis only is, in most cases, inadequate to convey a typical patient's overall level of psychopathology.

The present study also evaluated the prevalence of current AD in bipolar patients presenting with mania. Previous studies have evaluated this prevalence either in depressive phase,[1,10,12] remission phase,[32] or did not mention specifically about the current status of BP.[5,17,33,34] Thus, it is difficult to compare the results. Considering that about one-third of the sample had current one or more ADs, it is a significant finding.

The two groups with and without lifetime ADs were similar in terms of current age and other socio-demographic variables. The two groups had similar age at onset of BP, number of past episodes, number of hospitalizations, age at first hospitalization, total duration of hospitalization, comorbid substance use history, and family history of mental disorders. These corroborate with the findings of previous studies.[32,33,35] However, in a NIMH, STEP-BD study, it was found that age at onset of BP was significantly lower for patients with any lifetime AD than in patients without comorbid anxiety.[15] Another study found that BP with comorbid Axis I disorders (including ADs) have earlier age at onset of BP and greater first degree relatives with alcohol and drug abuse as compared to patients without comorbid Axis I disorder.[17] A direct comparison with the later study is not possible as they considered other Axis I comorbidity along with ADs such as substance use and eating disorders. In addition, the presence of difference in the age at onset in the above two later mentioned studies may have been the effect of difficult to treat patients being included in their sample (as the studies were conducted in specialist centers). Whereas the center in which the current study was conducted caters to a mixed group of BP patients.

The lifetime comorbid AD group as compared to those without AD had significantly more number of past depressive episodes, while they did not differ in the number of past manic episodes. This corroborates with the findings of Frank, et al.[36] which found significantly more median number of depressive episodes in bipolar patients with high lifetime panic spectrum symptoms while the two groups did not differ in median number of manic episodes. Another study did not find any difference in number of depressive episodes in the two groups[32] though the authors explained this by the nature of their sample that had in general 3.7 times more manic than depressive episodes (which in the current study was 1.6). Interepisodic persistent mental disturbance was found to be more in the AD group as in similar other study.[15]

It was found that the number of mood stabilizers administered either sequentially or in combination were significantly more in the AD group, though there was no significant difference in the type of mood stabilizer administered. There are no studies to compare this result as none has investigated the treatment differences in these two subgroups in the acute manic phase of illness. A study by Feske, et al.[9] did note that anxiety symptoms or panic attacks in bipolar patients irrespective of the phase of acute illness need more number of medications, either sequentially or in combination to achieve remission. When medications were individually assessed in the above mentioned study, no difference was found in the number of mood stabilizers administered and this difference was mainly contributed by the larger number of antidepressant trials in depressed patients. Since participants in the present study were treated according to the treating team's discretion and not according to a definite protocol, the prescribing practices were inclined toward early symptom control to cut short the duration of hospitalization. Findings thus illustrate more difficult to control manic symptoms in the AD group.

There was no significant difference in the total baseline ratings of the two BP subgroups in YMRS, BPRS, or HAM-A scores, while at day 45; scores on all the three scales were significantly higher in the AD group. The absence of difference at baseline between the two groups may have been due to the nature of the sample consisting of severely ill patients. The AD group reached lower levels of control of manic symptom at day 45 indicating more severe mania. These findings have some similarity with a study that noted that current and past anxiety symptoms (and not disorder) were associated with significantly longer time to remission in mania.[9] Though a direct comparison with this study is not possible, it remains to be corroborated. While when the overriding manic and psychotic symptoms were partially controlled (at day 45), presumably the inherent difference of anxiety symptoms between the two groups had become prominent, resulting in the significant difference.

In summary, the study shows a significant prevalence of comorbid ADs in BP I. This comorbidity has significant influence on BP course and severity, resulting in treatment variation.

In considering the above study a more important aspect is the implications for the diagnostic systems. Mood disorders, more often depression was assumed to be associated with states and experiences of anxiety. Mania (/BP) too as implicated from the study has high association with anxiety. This more than by chance association of mood problems (/disorders) with anxiety (symptoms/disorders) brings to us certain limitations of the diagnostic system. Winokur (1990),[37] writes that, “comorbidity, as it is used in psychiatry, is in fact describing multiformity of disease or the existence of two syndromes in the same individual, which is an aspect of multiformity.” He goes on to write, “there are more etiologies than there clinical syndromes and the appropriate term for multiformity could be cosyndromal.” To summarize, the heuristic axiom in the classificatory system though allows diagnostic simplicity, it may have compromised our understanding of BPs.

Several limitations of this study should be borne in mind while interpreting the results. There was a lack of a normal control group, another psychiatrically ill group or an epidemiological sample for comparison of the findings. The participants usually were severely ill, admitted in a public hospital setting, who might be different from a setting where the typical patients are moderately ill. This may result in selection bias, as psychiatric comorbidity is especially common in tertiary care centers. Though, due to lesser availability of psychiatric care in our country this setting caters to a mixed population of patients. The statistical power of the study was limited by its moderately large sample size. Other limitations were problems of reporting biases in retrospective data collection procedure, biases arising due to the non blinded status of the rater to the treatment of the patients, inherent difficulty with evaluation of comorbidity prevalence due to inconsistent definition of the threshold for caseness, overlap of diagnostic criteria, and rates being dependent on the extension of time frame explored. A significant preponderance of males to females in the sample (90.5% vs. 9.5%) allows limited generalization to the bipolar population though allows better understanding of hospitalized patients. A temporal relationship of the onset of either disorder was not analyzed in the study. In future a longitudinal study evaluating this may help in better understanding of the comorbidity.

CONCLUSION

Barring the abovementioned limitations the present study allows to understand the nuances of diagnostic hierarchies and implications of comorbidity (of AD) in BP. The study reveals that lifetime and current AD are found to be present in a large number of BP patients hospitalized due to acute mania, and is found to be associated with more severe BP course and more difficult to treat mania. These findings illustrate the importance of comorbid AD in BP in clinical/hospital practice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was conducted at the Central Institute of Psychiatry, Kanke, Ranchi. Special thanks to Prof. Daya Ram.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pini S, Cassano GB, Simonini E, Savino M, Russo A, Montgomery SA. Prevalence of anxiety disorders comorbidity in bipolar depression, unipolar depression and dysthymia. J Affect Disord. 1997;42:145–53. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(96)01405-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassano GB, Pini S, Saettoni M, Dell’Osso L. Multiple anxiety disorder comorbidity in patients with mood spectrum disorders with psychotic disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:474–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cosoff SJ, Hafner RJ. The prevalence of comorbid anxiety in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;32:67–72. doi: 10.3109/00048679809062708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers JE, Thase ME. Anxiety in the patient with bipolar disorder: Recognition, significance, and approaches to treatment. Psychiatr Ann. 2000;30:456–64. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen YW, Dilsaver SC. Comorbidity of panic disorder in bipolar illness: Evidence from the epidemiologic catchment area survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:280–2. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen YW, Dilsaver SC. Comorbidity for obsessive-compulsive disorder in bipolar and unipolar disorders. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59:57–64. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02752-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savino M, Perugi G, Simonini E, Soriani A, Cassano GB, Akiskal HS. Affective comorbidity in panic disorder: Is there a bipolar connection? J Affect Disord. 1993;28:155–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90101-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young LT, Cooke RG, Robb JC, Levitt AJ, Joffe RT. Anxious and non-anxious bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 1993;29:49–52. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feske V, Frank E, Mallinger AG, Houck PR, Fagiolini A, Shear MK, et al. Anxiety as a correlate of response to the acute treatment of bipolar I disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:956–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kruger S, Cooke RG, Hasey GM, Jorna T, Persad E. Comorbidity of obsessive compulsive disorder in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 1995;34:117–20. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00008-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraepelin E. Manic-depressive insanity and paranoia. Edinburgh: E and S Livingstone; 1921. In: Carlson ET, editor. Dementia praecox and paraphrenia together with manic-depressive insanity and paranoia. Birmingham: Classics of Medicine Library; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rihmer Z, Szadoczky E, Furedi J, Kiss K, Papp Z. Anxiety disorders comorbidity in bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar major depression: Results from a population based study in Hungary. J Affect Disord. 2001;67:175–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC, Rubinow DR, Holmes C, Abelson JM, Zhao S. The epidemiology of DSM-III-R bipolar I disorder in a general population survey. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1079–89. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, Fossey M, Sagduyu K, Frank E, et al. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: Data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2222–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pini S, Dell’Osso L, Mastrocinque C, Marcacci G, Papasogli A, Vignoli S, et al. Axis I comorbidity in bipolar disorder with psychotic features. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:467–71. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.5.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McElroy SL, Altshuler L, Suppes T, Keck PE, Jr, Frye MA, Denicoff KD, et al. Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship with historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:420–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strakowski SM, Tohen M, Stoll A, Faedda GL, Goodwin DC. Comorbidity in mania at first hospitalization. Amw J Psychiatry. 1992;149:554–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman MP, Freeman SA, McElroy SL. The comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: Prevalence, psychobiology, and treatment issue. J Affect Disord. 2002;68:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dilsaver SC, Chen YW, Swann AC, Shoaib AM, Tsai-Dilsaver Y, Krajewski KJ. Suicidality, panic disorder and psychosis in bipolar depression, depressive-mania and pure-mania. Psychiatry Res. 1997;73:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyd JH, Burke JD, Gruenberg E, Holzer CE, 3rd, Rae DS, George LK, et al. Exclusion criteria of DSM III. A study of co-occurrence of hierarchy-free syndromes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:983–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790210065008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA. 1990;264:2511–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chatterjee S, Kulhara P. Symptomatology, symptom resolution and short-term course in mania. Indian J Psychiatry. 1989;31:213–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chakrabarty S, Gill S. Coping and its correlates among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder: A preliminary study. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4:50–60. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulhara P, Basu D, Mattoo SK, Sharan P, Chopra J. Lithium prophylaxis of recurrent bipolar affective disorder: Long-term outcome and its psychosocial correlates. J Affect Disord. 1999;54:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar D, Ram D. Negative symptoms in single episode and multiepisode mania and its relation to outcome. Dissertation submitted to Central Institute of Psychiatry, Ranchi University. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown AS, Varma VK, Malhotra S, Jiloha RE, Conover SA, Susser ES. Course of affective disorder in a developing country setting. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:207–13. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199804000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joyce PR. Epidemiology of mood disorders. In: Gelder MG, Lopez-Ibor JJ Jr, Andreasen NC, editors. New oxford textbook of psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 695–701. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith AL, Weissman MM. Epidemiology. In: Paykel ES, editor. Handbook of affective disorders. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1992. pp. 111–29. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bland RC, Newman SC, Orn H. Age of onset of psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;338(suppl):43–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb08546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khanna R, Gupta N, Shaker S. Course of bipolar disorder in eastern India. J Affect Disord. 1992;24:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(92)90058-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamam L, Ozpoyraz N. Comorbidity of anxiety disorder among patients with bipolar I disorder in remission. Psychopathology. 2002;35:203–9. doi: 10.1159/000063824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henry C, Van den Bulke D, Bellivier F, Etain B, Rouillon F, Leboyer M. Anxiety disorders in 318 bipolar patients: Prevalence and impact of illness severity and response to mood stabilizer. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yerevanian B, Koek RJ, Ramdev S. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in mood disorder subgroups: A data from mood disorder clinic. J Affect Disord. 2001;67:167–73. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perugi G, Frare F, Toni C, Mata B, Akiskal HS. Bipolar II and unipolar comorbidity in 153 outpatients with social phobia. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:375–81. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.26270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frank E, Cyranowski JM, Rucci P, Shear MK, Fagolini A, Thase ME, et al. Clinical significance of lifetime panic spectrum symptoms in the treatment of patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:905–11. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winokur G. Concept of secondary depression and its relationship to comorbidity. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1990;13:567–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]