Abstract

The action of the environmental toxic Pb2+ on photosynthetic electron transport was studied in thylakoid membranes isolated from spinach leaves. Fluorescence and thermoluminescence techniques were performed in order to determine the mode of Pb2+ action in photosystem II (PSII). The invariance of fluorescence characteristics of chlorophyll a (Chl a) and magnesium tetraphenylporphyrin (MgTPP), a molecule structurally analogous to Chl a, in the presence of Pb2+ confirms that Pb cation does not interact directly with chlorophyll molecules in PSII. The results show that Pb interacts with the water oxidation complex thus perturbing charge recombination between the quinone acceptors of PSII and the S2 state of the Mn4Ca cluster. Electron transfer between the quinone acceptors QA and QB is also greatly retarded in the presence of Pb2+. This is proposed to be owing to a transmembrane modification of the acceptor side of the photosystem.

Introduction

Heavy metals play essential cofactor roles as structural and catalytic components of enzymes in many physiological processes required for the normal development of plants. Over the course of evolution, plants have developed different mechanisms that control and respond to the intake and accumulation of both essential and nonessential heavy metals. However, some heavy metals such as lead can be highly toxic to cells and cell organelle functions even at very low concentrations. Although the influence of excessive dose of heavy metals on the photosynthetic activity of plants has been studied in many cultivated species (1–3), the mechanism of heavy metal toxicity on photosynthesis is still a matter of great debate. Some evidence points to their involvement as inhibitors of electron transport in light reactions (4–5) and in the inhibition of enzyme activity in dark reactions by the direct blocking of protein functions or displacement of endogenous metals (6–7).

Lead, found in the environment, comes from both natural and anthropogenic sources. The metal is present in the soil, but also in all other environmental compartments: water, air and even living beings (8). The toxicity of a metal depends on its chemical state as well as on environmental factors (9–10). In soil, Pb can be found in ionic form, or bound to the soil particles (11). It has two oxidation states, namely 2+ and 4+. The tetravalent state is a strong oxidant but is not abundant in the environment. The divalent state, on the other hand, is more stable and prominent in the environment (12). The accumulation of Pb from atmospheric deposition or contaminated waste is largely stored in the soil, mainly in the surface layers and, more specifically, in the organic-rich layers (13). However, a small fraction of the metal is also absorbed by living organisms (micro-and meso-organisms, plants …etc.).

The photosystem II (PSII) complex is one of the two membrane-bound large multisubunit chlorophyll–protein complexes (PSII and PSI) of plants, algae and cyanobacteria embedded in the thylakoid membranes. PSII collects light energy, converts it into electro-chemical energy and drives electron transfer from water to PSI. On its acceptor side, PS II electron transport involves two acceptor quinones, QA and QB that are arranged around a non-heme iron. This non-heme iron is hexacoordinated by four histidines and two remaining ligand positions are taken by the oxygen atoms of bicarbonate as bidentate ligand (14–15). Further, the study of the effect of bicarbonate has suggested that the non-heme iron plays a role of an electron- transport regulator on the acceptor side of PSII. Although the precise mechanism of this process needs more study, the depletion of bicarbonate results in a decelerating of the electron transfer rate between QA and QB (16–20). The water oxidation complex (WOC) is located on the donor side of PSII. It is composed of a Mn4Ca cluster where the successive absorption of four quanta by PSII results in the advancement of the S-states cycle from S0 → S1 → S2 → S3 → (S4) → S0. The S4-state decays to the S0-state after the 4th flash with the concurrent oxygen evolution. The electrons are passed from the WOC to the reaction center P680+ through the secondary electron donor, TyrZ (Tyrosine 161 of D1 subunit) (21).

At present, there are only a few reports regarding the adverse action of Pb2+ on the photosynthetic apparatus (22 and references therein). A decline of the photochemical quantum yield of PSII was observed in isolated thylakoid membranes from spinach (23). It was proposed that Pb2+ affects oxygen evolution by removing extrinsic polypeptides and/or Ca2+ or Cl− ions associated with the water oxidizing complex of PSII (5, 24). Lead cation was also recently shown to affect PSI electron transport presumably due to binding near or at plastocyanin (25).

In this study, we have further investigated the mechanism of the action of Pb2+ in thylakoid membranes. The effects of the metal ion on the electron transport were studied using thermoluminescence and fluorescence spectroscopic techniques. Functional assays were used to determine the site of action and consequences of metal ion interaction in the thylakoid membranes and to explore the mode of action of the metal that causes the loss of photosystem II functions.

Materials and Methods

Thylakoid Membranes Isolation

Thylakoid membranes were prepared from fresh market spinach leaves (Spinacia oleracea L.) as described elsewhere (26), and were stored in the dark in 50 mM Hepes NaOH (pH 7.6), 0.33 M sorbitol, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM NaCl, and 10 mM KCl.

Chlorophyll Fluorescence Induction

Chlorophyll a fluorescence induction (FI) measurements were performed at room temperature using the Plant Efficiency Analyser (Hansatech, King’ Lynn, Norfolk, UK). The assay medium consisted of 50 mM Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.6), 0.33 M sorbitol, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, 10 mM KCl, and 10 mM NaCl with a final Chl concentration of 25 µg mL−1 for thylakoid membranes. Red excitation light peaking at 655 nm with an intensity of 1800 µmol m−2 s−1 was obtained from six light emitting diodes. As the fluorescence signal during the first 40 µs is ascribed to artifacts due to a delay in response time of the instrument, these data were not included in the analysis of FI traces.

Thermoluminescence

Measurements of thermoluminescence were performed using home-built equipment. The complete description of the design and functional aspects are described elsewhere (27–28). Thylakoid membranes were diluted to a final Chl concentration of 200 µg mL−1 in a medium containing 50 mM Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.6), 0.33 M sorbitol, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, 10 mM KCl, and 10 mM NaCl. About 300 µL of the suspension was added to the sample compartment (15 mm diameter) positioned just above Peltier plate and covered with a Hellma 202-OS disc window. The sample chamber was closed with a holder bearing the light guide connected to the photomultiplier. The sequence of incubation periods and flash illumination was as follows. The samples were pre-incubated for 120 s at 20°C. Then the temperature was brought down to 2°C within 36 s and kept for 60 s. Two actinic single turn-over saturating white flashes of about 2 µs pulse width (setting 10, XE-STC, Walz, Germany) were then applied to initiate charge separation in PSII. Finally, a linear warming (0.5°C s−1) of the samples in total darkness activated the recombination of PSII charge pairs that can be detected by the appearance of emission bands with characteristic temperature optima (27–28).

Fluorescence Measurements

Fluorometric experiments were carried out at room temperature 24°C with a Perkin Elmer LS55 Spectrometer equipped with a red-sensitive photomultiplier R928. Samples were excited at 434 nm and fluorescence emission spectra were measured from 600 to 800 nm as described by Rajagopal et al (2003) (29). The excitation and emission spectral widths were fixed at 5 and 2.5 nm, respectively, and emission spectra were corrected according to the photomultiplier sensitivity using the correction factor spectrum provided by Perkin-Elmer.

Flash-induced Fluorescence Decay Kinetics

In order to examine the reduction and oxidation kinetics of QA, Chl fluorescence rise and its relaxation in the dark were measured with FL3500 Fluorometer (Photon Systems Instruments, Brno, Czech Republic) as described previously (30–31). Thylakoid membranes (Chl concentration of 25 µg ml−1) were incubated for 3 min at room temperature in complete darkness without or with 50 µM of DCMU before initiating the fluorescence measurements. Samples were excited with a 20 µs red actinic flash from a LED peaking at 625 nm and prompt fluorescence was measured for 1 min. The first measurement was taken 20 µs after the flash was given. The traces were averaged to estimate the half-life times and amplitudes of the fluorescence decay components using the following three exponential functions:

| (1) |

where F(t) is the fluorescence value at time t, kn is the rate constant, An is the amplitude of the fluorescence relaxation phase, and F′ is the stable minimal fluorescence at the end of the decay.

Results

Chlorophyll Fluorescence Induction

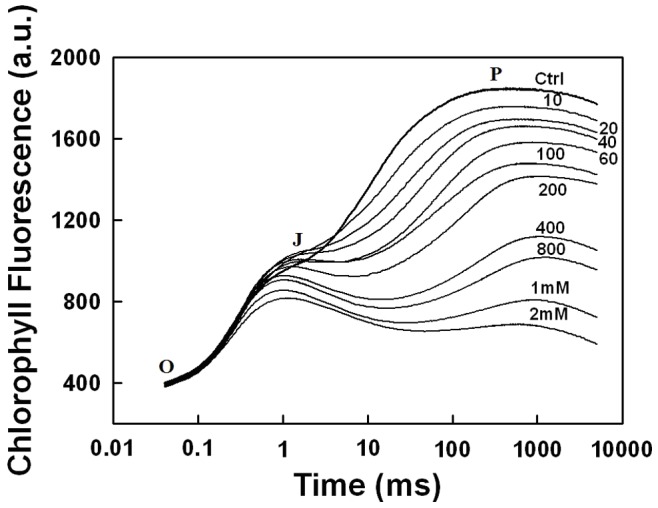

The kinetic curves of the fast Chl fluorescence rise were measured in isolated thylakoid membranes both untreated and those treated with various concentrations of PbCl2 as shown in Fig. 1. The FI traces, normalized at minimal values (F0), are characterized by a series of inflections in the rate of rise in the fluorescence intensity termed as OJIP transient (32–33). In isolated thylakoid membranes, the I step of the OJIP fluorescence, as observed by Bukhov et al 2003 (34), cannot be resolved visually due to the significant overlap between JI and IP phases (Fig. 1, Ctrl). However, Pospisil and Dau 2002 (35) and Boisvert et al 2006 (36) have decomposed the OJIP traces by fitting the experimental curves with a sum of three mono-exponential components. This method showed a good fit of the OJIP traces with the three components OJ, JI and IP, even though the inflection step I was absent (36). The I step can be restored by the addition of some different exogenous electron acceptors at the QB site of PSII (37). The treatment with different concentrations (10–400 µM) of lead increased the relative fluorescence intensity at J step while the rise towards the P step was retarded and the fluorescence intensity at P declined (Fig. 1). This suggests that the electron transfer between QA − and QB was slowed down with the increasing Pb2+ concentration. However, at Pb2+ concentrations greater than 400 µM, the OJ phase also began to decrease and the overall fluorescence induction was strongly damped (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the intensity of JIP phase also diminished with increased concentration of Pb cation. In other words, one observed a quenching of Chl fluorescence as the concentration of PbCl2 increased.

Figure 1. Typical traces of Chl a fluorescence rise in isolated thylakoid membranes in the absence (Ctrl) or in the presence of PbCl2 added in various concentrations (µM, unless specified in mM) as indicated by numbers adjacent to traces.

See Materials and methods for details.

Fluorescence of Chl a and MgTPP

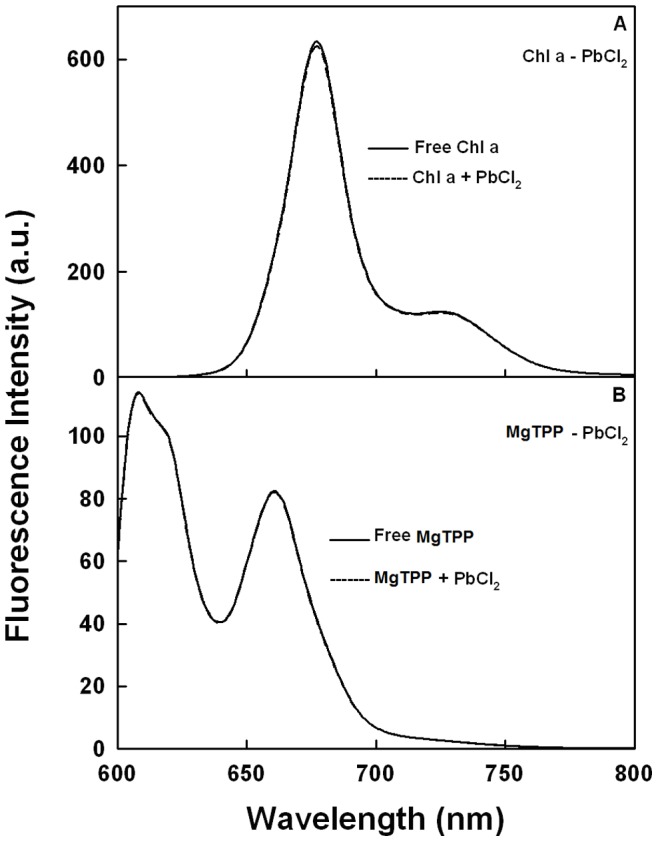

The observed Chl fluorescence quenching (Fig. 1) may be the result of the direct interaction of PbCl2 with the excited states of Chl of PSII thereby altering its radiative characteristics. Therefore, in order to verify this possibility, the fluorescence of Chl a in ethanolic solution was studied in absence and presence of PbCl2 (Fig. 2A). The fluorescence of Chl a in this solution exhibits a maximum at 675 nm, which is characteristic of monomeric Chl a (38). As seen from the figure, the fluorescence properties of Chl a practically remained unchanged upon addition of PbCl2. This suggests that PbCl2 has no direct effect on the excited singlet states of Chl a, and thus on its radiative properties. To further confirm this observation, fluorescence studies of MgTPP were performed in the presence of Pb2+ (Fig. 2B). The use of MgTPP is due to its structural analogy with Chl a as it is composed of the same porphyrin macrocycle with central Mg. In addition, the added advantage of using MgTPP is that it does not contain the phytol chain as is present in Chl a, and, as a result, can be more easily accessible to the additives. It is shown in Fig. 2B that PbCl2 had no effect on the fluorescence properties of MgTPP thus confirming the results obtained with Chl a.

Figure 2. Fluorescence emission spectra of: (A) ethanolic solution of Chl a (2.5 µM) alone (−) and in presence of 1 mM PbCl2 (–); (B) ethanolic solution of MgTPP (2.5 µM) alone (−) and in presence of 1 mM PbCl2 (–).

In both cases, the excitation wavelength was 433 nm.

Chlorophyll Fluorescence Induction Parameters

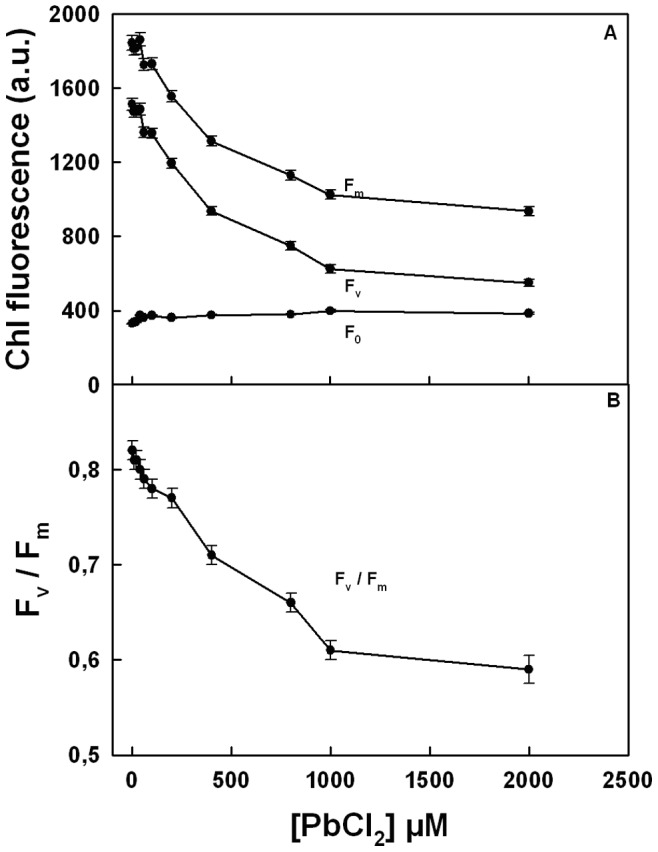

The Chl fluorescence properties of thylakoid membranes in the presence of Pb2+ were further subjected to the comprehensive analysis of fluorescence induction kinetics (Fig. 3). The initial fluorescence F0 (O-level), which describes the functional state of PSII reaction centers in terms of its openness in the dark-adapted state (39), remained virtually unchanged by the addition of Pb cations (Fig. 3A). However, in order to assess the effect of PbCl2 on the maximum quantum yield of the primary photochemistry of PSII in thylakoid membranes, the changes in the maximal fluorescence observed in dark adapted samples, Fm, when the excitons have been trapped and all the reaction centers of PSII are in closed state (40), were also examined. As seen from Fig. 3A, Fm greatly diminished as Pb2+ concentration increased. This decline in Fm leads to a decrease in the variable fluorescence Fv (Fv = Fm - F0) and, consequently, Fv/Fm, the maximal PSII photochemical quantum yield, also decreased (Fig. 3B). This decrease in Fv/Fm brings about a simultaneous decline in Fv/F0 (result not shown), a parameter that accounts for the simultaneous variations in Fm and F0 for the determination of the maximum photochemical quantum yield of PSII (41). Since, as noted in Fig. 3A, F 0 remains practically invariant with increasing Pb concentrations, the inhibitory effect of Pb2+ on the quantum yield of PSII photochemistry is, therefore, principally related to the changes in Fm.

Figure 3. Effect of various concentration of PbCl2 on Chl fluorescence induction parameters in thylakoids membranes.

(A) Fm, Fv and F0, vs PbCl2 (B) Fv/Fm vs PbCl2. Each point is the average of nine experiments.

Flash-induced Chl Fluorescence Decay Kinetics

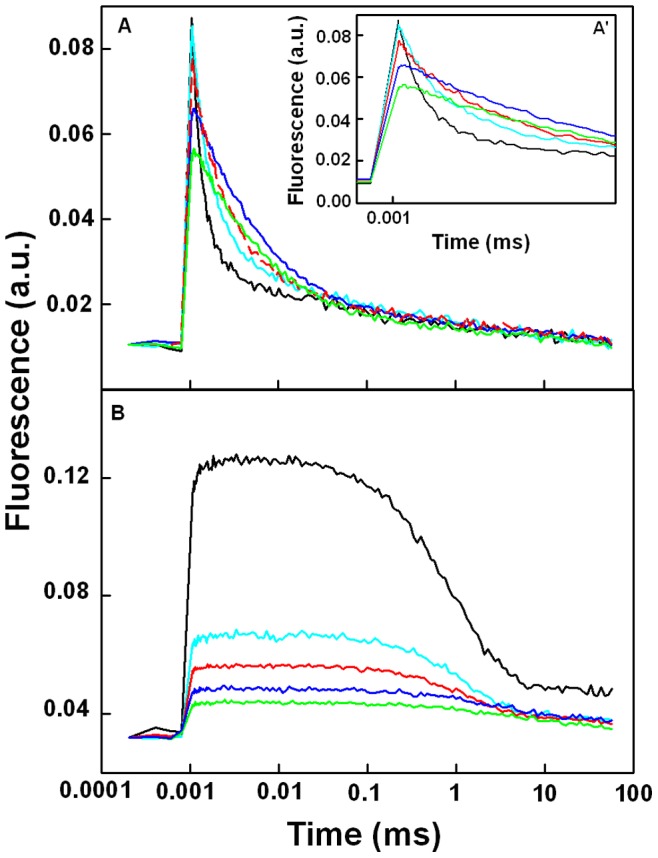

The fluorescence induction traces (Fig. 1) indicated that the reoxidation of QA was affected in the presence of PbCl2. This observation was further verified using the fluorescence properties of dark adapted isolated thylakoid membranes submitted to a single turnover flash and normalized at minimal values (Fig. 4A). The fluorescence rise induced by the flash is due to the reduction of QA, the primary quinone acceptor of PSII, and the decay thereafter in the dark is related to the reoxidation of QA − and consists of several kinetic phases. The amplitude of the fluorescence rise greatly decreased when the concentration of PbCl2 increased, especially at concentrations above 100 µM. In order to characterize quantitatively the fluorescence decay kinetics, the dark decay was fitted with three exponential components (Table 1). The fast component is attributed to the reoxidation of QA − by QB (42–43), the middle component is ascribed to the QA − reoxidation in PSII centers with an empty QB site and is limited by the diffusion time of PQ to the QB binding site. The slow phase is associated with the reoxidation of QA − through charge recombination with the S2 and/or S3 states of the Mn4Ca cluster (42–43). The amplitudes and the half-life times of the components are shown in Table 1. The amplitude of the fast phase greatly decreased with increasing amounts of PbCl2, this was accompanied by a strong increase in the half-life time of all three components of the decay kinetics (Table 1).

Figure 4. Effect of PbCl2 on the relaxation of single turnover flash-induced Chl fluorescence yields in thylakoids membranes with different lead concentrations: 0 (black), 10 (sky blue), 100 (red), 1000 (blue) and 2000 µM (green).

The measurements were performed in the absence (A) or in the presence (B) of 50 µM DCMU and all the traces were normalized. Each trace is the average of ten experiments.

Table 1. Effect of PbCl2 on the relative amplitude (A) and half-life time (t1/2) of the exponential decay components of Chl a fluorescence yield after a single turnover flash measured in thylakoid membranes in the absence and in the presence of 50 µM DCMU.

| Without DCMUPbCl2 (µM) | Fast Phase | Middle Phase | Slow Phase | |||

| t1/2 (±10 µs) | A (±5%) | t1/2 (±0.3 ms) | A (±3%) | t1/2 (0.4 s) | A (±2%) | |

| 0 | 430 | 69 | 6.1 | 22 | 5.9 | 9 |

| 10 | 690 | 61 | 7.5 | 26 | 7.1 | 13 |

| 100 | 987 | 45 | 11.3 | 35 | 12.1 | 20 |

| 1000 | 1440 | 28 | 16.8 | 43 | 15.6 | 29 |

| 2000 | 1590 | 19 | 18.2 | 46 | 17.2 | 35 |

| With DCMU PbCl2 (µM) | Fast Phase | Middle Phase | Slow Phase | |||

| t1/2 (±5 ms) | A (±4%) | t1/2 (±0.03 s) | A (±3%) | t1/2 (±0.3 s) | A (±2%) | |

| 0 | 298 | 41 | 1.79 | 47 | 18.5 | 12 |

| 10 | 1130 | 26 | 1.92 | 53 | 22.1 | 21 |

| 100 | 1560 | 19 | 2.25 | 58 | 23.6 | 23 |

| 1000 | – | – | 4.35 | 68 | 31.2 | 32 |

| 2000 | – | – | 4.86 | 69 | 31.9 | 31 |

The decay was also measured in the presence of DCMU that blocks electron transfer between QA − and QB (Fig. 4B). In this case, the reoxidation of QA − is owing to its charge recombination with the donor side of PSII. The fluorescence decay in the presence of DCMU can also be fitted with three exponential components (44–45). The fast component is due to the charge recombination with partially active Mn4Ca clusters, the middle component arise from the recombination of S2QB − charge pairs. The slowest component is associated with PSII with an oxygen evolving center in the S0 state before the flash was applied. The amplitudes of the middle and slow components increased with PbCl2 at the expense of the fast component and their half-life times increased (Table 1).

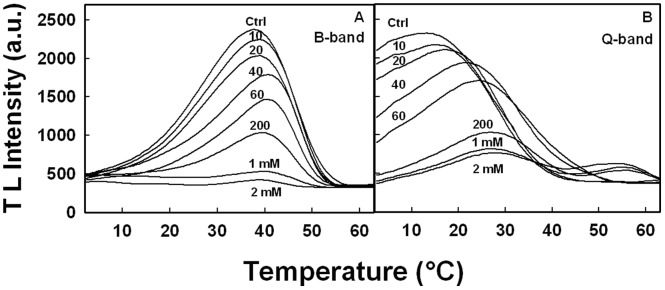

Thermoluminescence

Thermoluminescence was used to further explore the effects of PbCl2 on charge recombination between donor and acceptor sides of PSII. The TL glow curves for untreated (Ctrl) and Pb2+-treated thylakoid membranes following two single turn-over white flashes are displayed in Fig. 5A. The TL signal (Fig. 5A, Ctrl) attained its maximal intensity at the temperature of 38°C, characteristic of the temperature optimum for the B band appearing in the range between 30 and 40°C, as previously reported for this type of material (46–47). The B band is attributed to the charge recombination of S2/S3QB − pairs produced by linear electron transport in PSII (48–51). The intensity of the B band progressively diminished as the concentration of PbCl2 increased (Fig. 5A). The addition of 20 µM PbCl2 produced 13% decrease in TL intensity, and in the presence of 2 mM PbCl2, the TL intensity was suppressed completely. Also, the decline of the band was accompanied by an upshift of the maximal temperature (Tm) from 38°C to 41°C.

Figure 5. Thermoluminescence spectra measured in isolated thylakoid membranes in the absence (A) or presence of 50 µM DCMU.

PbCl2 was added in various concentrations (µM, unless specified in mM) as indicated by numbers adjacent to traces.

The changes in the amplitude and Tm of the B band could be related to changes in the properties of the Sn states of the Mn4Ca cluster and/or to modification of the QB binding site in the presence of PbCl2. In order to elucidate the site of action of PbCl2 in the electron transport chain, the TL glow curves were recorded following two single turn-over white flashes in the presence of 50 µM of PSII inhibitor DCMU, known to block the electron flow beyond QA. DCMU eliminated the B band with a simultaneous appearance of Q band with a maximum at 17°C, attributed to the back-flow of electrons from QA − to the S2-state (48–51) (Fig. 5B). The reason for the absence of B band is that since DCMU stops the electron flow past QA, the formation of QB − and state S3 is not realized (49). The addition of 20 µM PbCl2 already suppressed 12% of the Q band intensity. A progressive decrease of the Q band was observed when the concentration of PbCl2 was further increased. The addition of 2 mM PbCl2 caused the loss of more than 90% of Q band intensity. This loss was accompanied by a strong upshift of Tm from 17°C to 27°C.

Discussion

The negative action of Pb2+ on PSII photochemistry and electron transport, uninfluenced by PSI activity, was studied in thylakoid membranes using various approaches specific for PSII. Chlorophyll fluorescence induction kinetics measurements (Fig. 1) have shown that the fluorescence was greatly quenched when PbCl2 was added. Several authors postulated that damage caused by heavy metal ions (such as Zn2+, Cu2+, and Pb2+) to plants was due to the substitution of the central Mg from the Chl a molecules thus causing fluorescence quenching (52–54, 22). However, measurements of pure Chl a or MgTPP fluorescence in ethanolic solution (Fig. 2) have demonstrated that the addition of PbCl2 has no effect on the excited states of Chl a and the structure of the pigment remains intact. The fluorescence quenching observed during Chl fluorescence induction is, therefore, related to the modifications in the photochemical activity of PSII.

The OJIP traces constitute an essential tool to study the activity and integrity of the photosynthetic apparatus under different stress conditions, providing the information on PSII photochemistry such as the electron transport on both donor and acceptor sides of the photosystem (32–33, 55). The IP step of the Chl fluorescence induction has been correlated with the photoreduction of the PQ pool (56–57). Thus, the observed decline in IP phase indicates a strong inhibition of the accumulation of reduced PQ especially at Pb2+ concentrations above 400 µM (Fig. 1). This coincided with a decrease in the Fv/Fm values due to a decrease in Fm (Fig. 3) (23). This part of the induction is known to be more sensitive to the unfavourable treatments in comparison with the photochemical phase (OJI) (58). Indeed, the perturbation in the structure-function relations of the WOC has been shown to correlate with the quenching of the IP fluorescence rise that results in a decline of Fm (36, 58). The above is in line with the previous reports showing that Pb2+ causes the release of extrinsic polypeptides associated with the WOC together with the Ca2+ and Cl− required as cofactors (5, 25). Therefore, the inhibition of JIP rise and the more significant damping of the whole fluorescence induction kinetics above 400 µM Pb2+ are the result of the disorganization of the WOC causing the lack of electron flow towards the acceptor side of PSII. The damage of the Mn4Ca cluster is also supported by the decline of both Q and B thermoluminescence bands. Such inhibition of both S2QA − and S2QB − charge recombination (Q and B band, respectively) shows that the S2 state of the WOC becomes unavailable as the common recombination partner with increasing concentrations of PbCl2 and indicates a dysfunction of the WOC.

On the other hand, the OJ phase is related to the reduction state of QA (56, 59). The relative increase of OJ in the presence of low concentrations of PbCl2 (Fig. 1) is strongly indicative of a delayed electron transfer from QA − to QB. This was indeed verified using the measurements of Chl fluorescence decay kinetics following a single turn-over flash (Fig. 4). The fluorescence decay was greatly retarded with the life-time of all three components being significantly increased even at concentrations below 400 µM PbCl2 (Table 1). The amplitude of the fast component, attributed to electron transfer from QA − to QB, diminished with a concurrent increase of the other components. Also, the decreased rate of QA − reoxidation resulted in an increased amplitude of the slow component attributed to the back reactions with the S2 state of the Mn4Ca cluster (42–43). This corresponds with the increased amplitude of the middle component of the decay measured in the presence of DCMU (Table 1), a component also attributed to S2/QA − recombination (44–45). Therefore, the population of PSII centers with a reduced QA that is reoxidized through S2/QA − recombination is increased but the rate of this reoxidation is strongly declined most likely due to the stabilization of the S2 state of the WOC (see below).

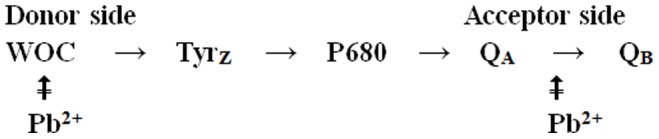

The delayed reoxidation of QA − maybe interpreted in terms of an active site of Pb2+ being near QA or QB. Indeed, similar data were previously used to conclude that an inhibitory site of various metal cations was located between QA and QB (Fig. 6) (60–62). However, the destabilization of the WOC discussed above may also cause the delayed QA − reoxidation. It was indeed shown that the removal of the extrinsic polypeptides or Ca2+ from the WOC can cause the diminished rate of QA − reoxidation through a transmembrane conformational effect (42). Removal of Ca2+ from the WOC also produces a modification in the mid-point potential of QA thus altering the electron transfer process between QA and QB (63, 43). It can be postulated that this conformational change modifies the bicarbonate binding that is required for proper electron transfer from QA − to QB (17, 18). Therefore, it is plausible that the action of Pb2+ at the WOC would cause this same transmembrane effect as was also proposed for the inhibitory action of Ni2+ and polyamines (64–65). This view is supported by the strong progressive upshift of the Tm of Q and B thermoluminescence bands with increasing concentrations of Pb2+ (Fig. 5). Such large increase in thermoluminescence temperature was previously associated with the stabilization of the S2 state of the WOC due to the modification in the ligand environment of the Mn4Ca complex following the depletion in Cl− or in 33 kDa extrinsic polypeptide (66–67). Therefore, the shift of Tm towards higher temperatures may be due to a change in the population of PSII centers with a stabilized S2 state owing to the action of Pb2+ causing a retarded QA − reoxidation at low Pb2+ concentrations. This may represent an intermediate step in the inhibition of the WOC that precedes the serious damping of the fluorescence induction observed at high Pb2+ concentrations (Fig. 1).

Figure 6. Schematic representation of the proposed inhibitory sites of Pb2+ in PSII.

Although an active site of Pb2+ at or near QB cannot be fully excluded, the negative action of Pb2+ is postulated to proceed in two steps. During the intermediate step, the environment of the Mn4Ca complex is disorganized and the S2 state of the WOC is stabilized which consequently affects QA − reoxidation and increases S2/QA − charge recombination (though the recombination proceeds at a slower rate compared to the control). During the final phase, the WOC is damaged more seriously leading to a loss of charge recombination and of PQ reduction.

Funding Statement

This work is supported by a grant from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Prasad MNV, Strzałka S (1999) Impact of heavy metals on photosynthesis. In: Heavy Metal Stress in Plants, from Molecules to Ecosystems. Prasad MNV, Hagemeyer J, editors. Berlin: Springer. 117p. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaffer M (2001) Waste lands: the threat of toxic fertilizer. California’s Advocate for the Public Interest Los Angeles CA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker AJM, Walker PL (1990) Ecophysiology of metal uptake by tolerant plants, heavy metal tolerance in Plants. In: Shaw AJ. Evolutionary Aspects. CRC Press Boca Raton. 155–177. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giardi MT, Masojidek J, Godde D (1997) Discussion on the stresses affecting the turnover of the D1 reaction center II protein. Plant Physiol 101: 635–642. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rashid A, Camm EL, Ekramoddoullah KM (1994) Molecular mechanism of action of Pb2+ and Zn2+ on water oxidizing complex of photosystem II. FEBS Lett 350: 296–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chugh LK, Sawhney SK (1999) Photosynthetic activities of Pisum sativum seedlings grown in presence of cadmium. Plant Physiol Biochem 37: 297–303. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Van Assche F, Clijsters H (1990) Effects of metals on enzyme activity in plants. Plant Cell Environ 13: 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morlot M (1996) Aspects analytiques du plomb dans l’environnement, édition Lavoisier TEC&DOC.

- 9. Babich H, Stotzky G (1980) Environmental factors that influence the toxicity of heavy metals and gaseous pollutants to microorganisms. Crit Rev Microbiol 8: 99–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wani PA, Khan MS, Zaidi A (2007) Chromium reduction, plant growth-promoting potentials and metal solubilization by Bacillus sp. isolated from alluvial soil. Curr Microbiol 54: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raskin I, Ensley BD (2000) Phytoremediation of toxic metals; using plants to clean up the environment. John Wiley and Sons New York.

- 12.Callender E (2003) Heavy Metals in the Environment-Historical Trends. In: Lollar BS, editors. Environmental Geochemistry. Treatise on Geochemistry. Elservier-Pergamon, Oxford. 67–105.

- 13. Sterckeman T, Douay F, Proix N, Fourrier H (2000) Vertical distribution of Cd, Pb and Zn in soils near smelters in the North of France. Environ Pollut 107: 377–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrouleas V, Crofts AR (2005) The iron-quinone acceptor complex. In: Photosystem II. The light-driven water:plastoquinone oxidoreductase. Wydrzynski T Satoh K, editors. Springer Dordrecht The Netherlands. 177–206.

- 15. Guskov A, Kern J, Gabdulkhakov A, Broser M, Zouni A, et al. (2009) Cyanobacterial photosystem II at 2.9-angstrom resolution and the role of quinones, lipids, channels and chloride. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16: 334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jursinic P, Warden J (1976) Govindjee (1976) Major site of bicarbonate effect in system-II reaction evidence from ESR signal-IIvf, fast fluorescence yield changes and delayed light-emission. Biochim Biophys Acta 440: 322–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robinson HH, Eaton-Rye JJ, van Rensen S (1984) Govindjee (1984) The effects of bicarbonate depletion and formate incubation on the kinetics of oxidationreduction reactions of the Photosystem II quinone acceptor complex. Z Naturforsch C 39: 382–385. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eaton-Rye JJ (1988) Govindjee (1988) Electron-transfer through the quinone acceptor complex of Photosystem-II after one or 2 actinic flashes in bicarbonate-depleted spinach thylakoid membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta 935: 248–257. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farineau J, Mathis P (1983) Effect of bicarbonate on electron transfer between plastoquinones in Photosystem II. In: Inoue Y, Crofts AR, Govindjee, Murata N, Renger G, Satoh K, editors. The oxygen evolving system of photosynthesis. Academic Press Inc. 317–325.

- 20. Van Rensen JJS, Tonk WJM, Debruijn SM (1988) Involvement of bicarbonate in the protonation of the secondaryquinone electron-acceptor of Photosystem II via the nonheme iron of the quinone–iron acceptor complex. FEBS Lett 226: 347–351. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Renger G (2011) Light induced oxidative water splitting in photosynthesis: Energetics, kinetics and mechanism. J Photochem Photobiol B 104: 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qufei L, Fashui H (2009) Effects of Pb2+ on the structure and function of photosystem II of Spirodela polyrrhiza. Biol Trace Element Res 129: 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boucher N, Carpentier R (1999) Hg2+, Cu2+, and Pb2+-induced changes in photosystem II photochemical yield and energy storage in isolated thylakoid membranes: A study using simultaneous fluorescence and photoacoustic measurements. Photosynth Res 59: 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rashid A, Popovic R (1990) Protective role of CaCl2 against Pb2+ inhibition in Photosystem II. FEBS Lett 271: 181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belatik A, Hotchandani S, Tajmir-Riahi HA, Carpentier R (2013) Alteration of the structure and function of photosystem I by Pb2+. J Photochem Photobiol B In Press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26. Joly D, Bigras C, Harnois J, Govindachary S, Carpentier R (2005) Kinetic analyses of the OJIP chlorophyll fluorescence rise in thylakoid membranes. Photosynth Res 84: 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ducruet JM (2003) Chlorophyll thermoluminescence of leaf discs: simple instruments and progress in signal in interpretation open the way to new ecophysiological indicators. J Exp Bot 54: 2419–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gauthier A, Govindachary S, Harnois J, Carpentier R (2006) Interaction of N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine with photosystem II as revealed by thermoluminescence: reduction of the higher oxidation states of the Mn cluster and displacement of plastoquinone from the QB niche. Biochim Biophys Acta 1757 1547–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rajagopal S, Egorova EA, Bukhov NG, Carpentier R (2003) Quenching of excited states of chlorophyll molecules in submembrane fractions of photosystem I by exogenous quinones. Biochim Biophys Acta 1606: 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Putrenko II, Vasiliev S, Bruce D (1999) Modulation of flash-induced photosystem II fluorescence by events occurring at the water oxidizing complex. Biochemistry 38: 10632–10641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ono TA, Noguchi T, Nakajima Y (1995) Characteristic changes of function and structure of photosystem II during strong light photoinhibition under aerobic conditions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1229: 239–248. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strasser RJ, Govindjee (1992) On the O–J–I–P fluorescence transients in leaves and D1 mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. In: Murata N, editors. Research in Photosynthesis, Kluwer Academic Publishers Dordrecht The Netherlands. 23–32.

- 33. Strasser RJ, Srivastava A (1995) Govindjee (1995) Polyphasic chlorophyll a fluorescence transient in plants and cyanobacteria. Photochem Photobiol 61: 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bukhov NG, Egorova EA, Govindachary S, Carpentier R (2004) Changes in polyphasic chlorophyll a fluorescence induction curve upon inhibition of donor or acceptor side of photosystem II in isolated thylakoids. Biochim Biophys Acta 1657: 121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pospisil P, Dau H (2002) Valinomycin sensitivity proves that light-induced thylakoid voltages result in millisecond phase of chlorophyll fluorescence transients. Biochim Biophys Acta 1554: 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boisvert S, Joly D, Carpentier R (2006) Quantitative analysis of the experimental O–J–I–P chlorophyll fluorescence induction kinetic apparent activation energy and origin of each kinetic step. FEBS J 273: 4770–4777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Joly D, Carpentier R (2007) The oxidation/reduction kinetics of the plastoquinone pool controls the appearance of the I-peak in the O–J–I–P chlorophyll fluorescence rise: Effects of various electron acceptors. J Photochem Photobiol B 88: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barazzouk S, Kamat P, Hotchandani S (2005) Photoinduced electron transfer between chlorophyll a and gold nanoparticles. J Phys Chem 109: 716–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Anderson JM, Park YI, Soon WS (1998) Unifying model for the photoinactivation of Photosystem II in vivo under steady-state photosynthesis. Photosynth Res 56: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lazar D (2006) The polyphasic chlorophyll a fluorescence rise measured under high intensity of exciting light Funct Plant Biol. 33: 9–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Babani F, Lichtenthaler HK (1996) Light-induced and age-dependent development of chloroplasts in etiolated barley leaves as visualized by determination of photosynthetic pigments, CO2 assimilation rates and different kinds of chlorophyll fluorescence ratios. J Plant Physiol 148: 555–566. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Putrenko II, Vasiliev S, Bruce D (1999) Modulation of flash-induced photosystem II fluorescence by events occurring at the water oxidizing complex. Biochemistry 38: 10632–10641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pospisil P, Tyystjärvi E (1999) Molecular mechanism of high temperature-induced inhibition of acceptor side of photosystem II. Photosynth Res 62: 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mamedov F, Stefanson H, Albersson PA, Styring S (2000) Photosystem II in different parts of the thylakoid membrane: a functional comparison between different domains. Biochemistry 39: 10478–10486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mamedov F, Rintamaïki E, Aro EM, Andersson B, Styring S (2002) Influence of protein phosphorylation on the electron-transport properties of Photosystem II. Photosynth Res 74: 61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vass I (1996) Govindjee (1996) Thermoluminescence from the photosynthetic apparatus. Photosynth Res 48: 117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sane PV (2004) Thermoluminescence: a Technique for Probing Photosystem II. In: Carpentier R, editors. Photosynthesis Research Protocols Humana Press. Totova New Jersey USA. 229–248. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48. Rutherford AW, Crofts AR, Inoue Y (1982) Thermoluminescence as a probe of photosystem II photochemistry the origin of the flash-induced glow peaks. Biochim Biophys Acta 682: 457–165. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Belatik A, Essemine J, Hotchandani S, Carpentier R (2012) Afterglow thermoluminescence band measured in isolated chloroplasts. Photochem Photobiol 88: 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ducruet JM, Roman M, Ortega JM, Janda T (2005) Role of the oxidized secondary acceptor QB of photosystem II in the delayed afterglow chlorophyll luminescence. Photosynth Res 84: 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Demeter S, Vass I (1984) Charge accumulation and recombinaition in photosystem II studied by thermoluminscence. Participation of the primary acceptor Q and secondary B in the generation of thermoluminescence in chloroplasts. Biochim Biophys Acta 764: 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rebeiz CA, Castelfranco PA (1973) Protochlorophyll and chlorophyll biosynthesis in cell-free systems from higher plants. Ann Rev Plant Physiol 24: 129–72. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wu JT, Lorenzen H (1984) Effect of copper on photosynthesis in synchronous Chlorella cells. Bot Bull Acad Sinica 25: 125–32. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wu X, Liau C, Chunxiang Q, Hao H, Xianqing L, et al. (2008) Effects of lead on activities of photochemical reaction and key enzymes of carbon assimilation in spinach chloroplast. Biol Trace Element Res 126: 269–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kruger GHJ, Tsimilli-Michael M, Strasser RJ (1997) Light stress provokes plastic and elastic modifications in structure and function of Photosystem II in camellia leaves. Plant Physiol 101: 265–277. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Boisvert S, Joly D, Carpentier R (2006) Quantitative analysis of the experimental O-J-I-P chlorophyll fluorescence induction kinetics: Apparent activation energy and origin of each kinetic step. FEBS J 273: 4770–4777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Joly D, Carpentier R (2007) The oxidation/reduction kinetics of the plastoquinone pool controls the appearance of the I-peak in the O-J-I-P chlorophyll fluorescence rise: Effects of various electron acceptors. J Photochem Photobiol B 88: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schmidt W, Neubauer C, Kolbowski J, Schreiber U, Urbach W (1990) Comparaison of effects of ar pollutants (SO2, O3, NO2) on intact leaves by measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence and P700 absorbance changes. Photosynth Res 25: 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gauthier A, Joly D, Boisvert S, Carpentier R (2010) Period-four modulation of photosystem II primary quinone acceptor (QA) reduction/oxidation kinetics in thylakoid membranes. Photochem Photobiol 86: 1064–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mohanty N, Vass I, Demeter S (1989) Impairment of photosystem II activity at the level of secondary quinone electron acceptor in chloroplasts treated with cobalt, nickel and zinc ions. Physiol Plant 76: 386–390. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yruela I, Gatzen G, Picorel R, Holzwarth AR (1996) Cu(II)-inhibitory effect on Photosystem II from higher plants. A picoseconds time-resolved fluorescence study. Biochemistry 35: 9469–9474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sigfridsson KGV, Bernat G, Mamedov F, Styring S (2004) Molecular interference of Cd2+ with photosystem II. Biochim Biophys Acta 1659: 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Krieger A, Weis E, Demeter S (1993) Low pH-induced Ca2+ ion release in the water-splitting system is accompanied by a shift in the midpoint redox potential of the primary quinone acceptor QA . Biochim Biophys Acta 1144: 411–418. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Boisvert S, Joly D, Leclerc S, Govindachary S, Harnois J, et al. (2007) Inhibition of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II and depletion of extrinsic polypeptides by nickel. Biometals 20: 879–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Beauchemin R, Gauthier A, Harnois J, Boisvert S, Govindachary S, et al. (2007) Spermine and Spermidine inhibition of photosystem II: Disassembly of the oxygen evolving complex and consequent perturbation in electron donation from Tyrz to P680+ and the quinone acceptors QA − to QB . Biochim Biophys Acta 1767: 905–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Homann PH, Madabusi LV (1993) Modification of the thermoluminescence properties of Ca2+ depleted photosystem II membranes by the 23 kDa extrinsic polypeptide and by oligocarboxylic acids. Photosynth Res 35: 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vass I, Ono T, Inoue Y (1987) Stability and oscillation properties of thermoluminescent charge pairs in the O2-evolving system depleted of Cl− or the 33 kDa extrinsic protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 892: 224–235. [Google Scholar]