Abstract

Background

We examined the possibility that CXCL16 recruits endothelial cells (ECs) to developing neovasculature in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) synovium.

Methods

We utilized the RA synovial tissue (ST) severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse chimera system to examine human dermal microvascular endothelial cell (HMVEC) and human endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) recruitment into engrafted human synovium injected intragraft with RA synovial fluid (SF) immunodepleted of CXCL16. CXCR6 deficient (CXCR6−/−) and wild-type (Wt) C57BL/6 mice were primed to develop K/BxN serum induced arthritis and evaluated for angiogenesis. HMVECs and EPCs from human cord blood were also examined for CXCR6 expression by immunofluorescence and signaling activity for CXCL16.

Results

We found that CXCR6 is prominently expressed on human EPCs and HMVECs and can be upregulated by interleukin-1β (IL-1β). SCID mice injected intragraft with RA SF immunodepleted of CXCL16 showed a significant reduction in EPC recruitment. Using the K/BxN serum induced inflammatory arthritis model, CXCR6−/− mice showed profound reductions in hemoglobin (Hb) levels that correlated with reductions in monocyte and T-cell recruitment to arthritic joint tissue in CXCR6−/− compared to wildtype (Wt) mice. We also found that HMVECs and EPCs respond to CXCL16 stimulation but have unique signal transduction pathways and homing properties.

Conclusion

These results indicate that CXCL16 and its receptor CXCR6 may be a central ligand-receptor pair that can be highly correlated with EPC recruitment and blood vessel formation in the RA joint.

Keywords: CXCL16, CXCR6, endothelial progenitor cells, vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, rheumatoid arthritis, chemotaxis

Introduction

RA is a debilitating inflammatory joint disorder affecting approximately 2% of the population worldwide (1). Autoimmune mediated inflammation has long been known to be the primary mechanistic component of the cartilage and bone destruction observed in RA joints (2). Growth of new blood vessels (i.e., neovascularization) in the joint lining (synovium) is characteristic of this inflammatory response and is observed early in RA pathogenesis (3). Synovial neovascularization is of pivotal importance in the progression of RA by creating a direct conduit for the entrance into the joint of circulating leukocytes that exacerbate inflammation. Neovascularization occurs by one of two mechanisms: angiogenesis, the replication and reorganization of preexisting microvascular ECs (4), or by vasculogenesis, the recruitment of EPCs that subsequently incorporate into the existent tissues and differentiate into mature functional ECs (5).

Chemokines are small soluble molecules that recruit destructive pro-inflammatory immune cells to the RA synovium. Some “CXC” chemokines show angiogenic activity (6–10). Although characterizing chemokine function has defined many in vitro functions, there continues to be a need for information regarding the specific role of chemokines in animal models of RA. Interestingly, a recent study reported high percentages (96 ± 2%; mean ± SEM) of primary BM derived murine mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) expressing CXCR6, the only known receptor for CXCL16, on their cell surface. Notably, CXCR6 was also expressed on a high proportion (95 ± 1%) of human BM derived MSCs (11). Considering the known function of this receptor in relation to recruitment and homing of immune cells (12), it is reasonable to hypothesize that CXCR6 may also be involved in the recruitment and homing of MSCs to inflamed tissues, likely for the purposes of tissue regeneration and/or vasculogenesis (11).

Growing evidence has suggested that EPCs contribute to the homeostasis of the physiologic vascular network (13), as well as contribute to vascular remodeling of RA synovium by recruiting BM derived circulating EPCs (14). Our data shows a distinct role for CXCL16 as an important EC angiogenic and EPC recruitment factor to human synovium in vivo. We have previously shown that RA synovial fluid (SF) contains very highly elevated concentrations of soluble CXCL16 compared to other chemokines (12), and herein, that both HMVECs and EPCs express CXCR6. We also show that HMVECs upregulate CXCR6 in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli. For these reasons, we believe that selective regulation of EC mediated migration may be a viable therapeutic strategy for limiting vasculogenesis in the RA synovium.

Materials and Methods

Rodents

Animal care at the Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine at the University of Michigan is supervised by a veterinarian and operates in accordance with federal regulations. SCID mice were obtained from National Cancer Institute (NCI). K/BxN Wt and CXCR6−/− knockout mice were bred in house according to the guidelines of the University Committee on the Use and Care of Animals. All rodents were given food and water ad libidum throughout the entire study and were housed in sterile rodent micro-isolator caging with filtered cage tops in a specific pathogen-free environment to prevent infection. All efforts were made to reduce stress or discomfort to all animals.

Isolation of EPC CD34+ cells from cord blood

Human EPCs were isolated from cord blood from granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) mobilized leukopheresis samples on the basis of CD133 expression, using an antibody coupled magnetic bead cell isolation system (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Human umbilical cord blood was collected by the method of Moore et al. (15), as previously described (14). To confirm purity of the EPCs, isolated cell populations were subjected to flow cytometry analysis as described previously (16), (17). EPCs with appropriate cell markers (CD34+, CD133+, CD14−) were used in chimeras and related in vitro studies.

Fluorescence microscopy of ECs

HMVECs (passage 9 or less) were plated at 20,000/well in 8-well Labtek chamber slides in 0.1 % bovine serum albumen (BSA) endothelial basal medium (EBM) without antibiotics. Some HMVECs were stimulated with interleukin-1β (IL-1β) for 24 hours. The next day, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% formalin for 30 minutes at room temperature, washed again with PBS, and fixed with cold acetone for 20 minutes. EPCs were also plated at 20,000/well in 8-well Labtek chamber slides in Stem-span and fixed similarly. For staining, HMVECs and EPCs were blocked with 20% fetal bovine serum and 5% donkey serum for 1 hour at 37°C. Mouse anti-human CXCR6 antibody (R&D Systems) or mouse anti-human vWF antibody (DAKO) were used as primary antibody. Fluorescent conjugated secondary antibody was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR), and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used to stain cell nuclei.

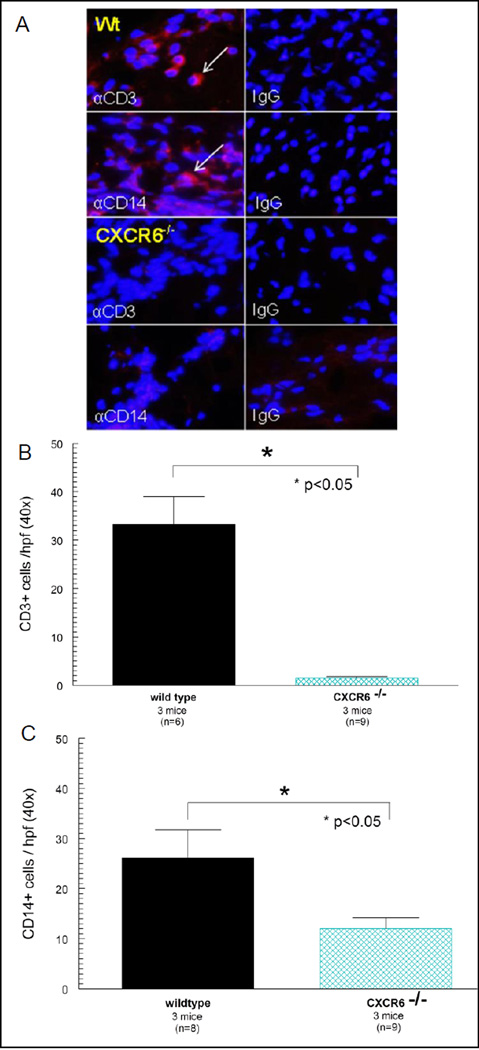

Immunofluorescence for leukocytes

Immunofluorescence histology was performed as previously described (12). Briefly, rat anti-mouse CD3 or CD14 antibodies (final concentration 10µg/ml; both from BD Biosciences) were added as primary antibodies and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Rat IgG served as the respective negative control. After washing twice with PBS, Alexa 488–labeled goat anti-rat antibody was added and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. After washing with PBS, nuclei were counterstained with 4-,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and coverslipped. Serial sections were examined with a BX51 Fluorescence Microscope System using DP Manager imaging software (Olympus America, Melville, NY). Photographs were merged, and CD3+ or CD14+ macrophages were identified by fluorescence microscopy.

CXCL16 induces HMVEC chemotaxis

HMVECs (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) were maintained in growth factor complete EBM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were between passages 7 and 10, and did not display discernable phenotypic changes when observed before each assay. Cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. HMVEC migration in vitro was tested using a modified 48-well Boyden chemotaxis chamber (Neuroprobe, Cabin John, MD) as described previously (18). Data are expressed as the number of cells migrating per well.

In vitro capillary morphogenesis assay shows that CXCL16 is angiogenic in vitro

HMVECs were suspended in EBM medium with 0.1% FBS and seeded in Labtek chamber slides on growth factor reduced Matrigel (Becton Dickinson, Bedford, MA) at a density of 1.6 x104 cells per chamber. Cells were treated with recombinant human (rhu) CXCL16 (100 ng/ml), 4-phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 50 nmol/l), or dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) immediately after plating (note that PMA is dissolved in DMSO so it is included as a control). PMA and DMSO served as positive and negative controls, respectively. After 18 hours, capillary morphogenesis was examined under a phase-contrast microscope and node formation evaluated by an investigator blinded to the experimental setup. Capillary formation was defined as the induction of a minimum of three separate capillary events by HMVECs in growth factor reduced Matrigel as previously described (18).

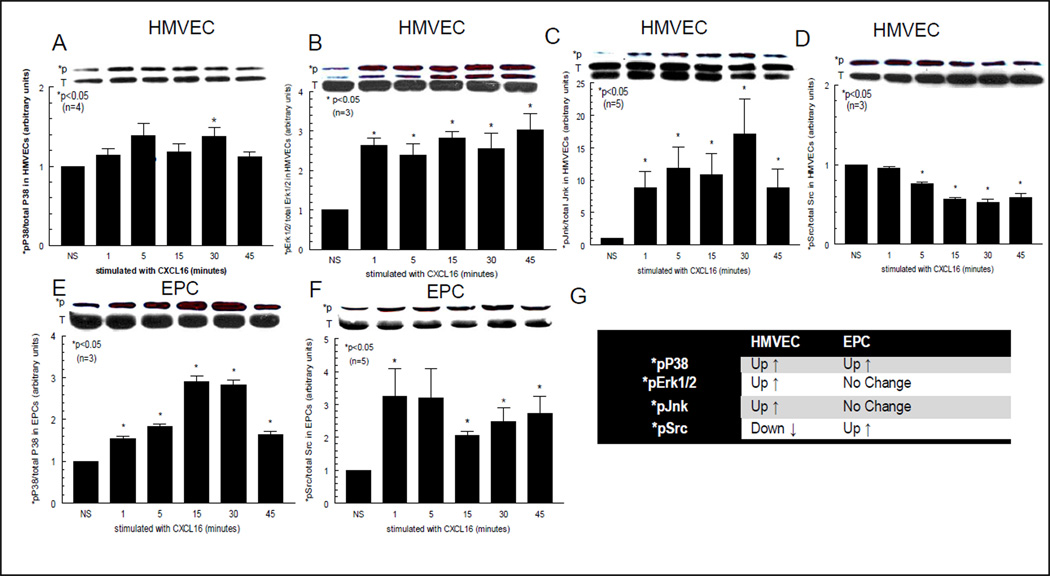

Western blotting and cell signaling in HMVECs and EPCs

Western blotting on ECs was done as previously described (12, 19). HMVECs and EPCs were plated at 1x105 in 0.1% FBS/EBM (HMVECs) or Stem-spam media (EPCs), and stimulated with CXCL16 (80ng/ml). Blots were probed using rabbit antibodies to selected phosphorylated (*p) signaling molecules (all from Cell Signaling Technology): anti-*p-P38, anti-*p-Erk1/2, anti-*p-Jnk and anti-*p-Src. The immunoblots were stripped and reprobed with rabbit antibody to the total amount of each signaling molecule (containing phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of the same molecule) to verify equal loading. The upper band for each respective blot show the phosphorylated signaling molecule only. The lower band shows the total (T) amount of the signaling molecule containing phosphorylated (*p) and unphosphoylated forms of each molecule. Therefore, the upper blot is an indication of the amount of phosphorylated protein contained in the lower band for each signaling molecule. For some studies, HMVECs and EPCs were probed for CXCR6 expression with and without IL-1β stimulation. The immunoreactive protein bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Densitometric analysis of the bands was performed using Un-Scan-It software, version 5.1 (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT).

RA SF neutralization studies

For neutralization of CXCL16, diluted SF (1:300 with PBS) was pre-incubated with a neutralizing polyclonal goat anti-human CXCL16 antibody (catalog no. AF976; R&D Systems) at a concentration of 135 ng/100µl diluted SF (from undiluted SF samples containing ~45ng/ml CXCL16). Control (sham-depleted) SF samples were incubated in a similar manner but with a corresponding control nonspecific antibody (goat IgG; R&D Systems), as recommended by the vendor and as previously described in experiments using RA SF (20).

K/BxN serum induced arthritis model

To generate arthritic K/BxN mice, K/B positive mice were crossed with NOD/LTj mice as previously described (21). Naïve mice at the age of 5–7 weeks were injected with 150µl of K/BxN serum i.p., and this was considered to be day 0 of arthritis. Another injection of 150µl of K/BxN serum followed on day 2. Robust arthritis with severe swelling of the joints typically developed on day 5. Articular index (AI) scores and joint circumferences were determined starting on day 0 and scored at least every other day up to day 23 after arthritis induction of arthritis as described previously for rat adjuvant induced arthritis (22). Mouse ankles were harvested for histology or made into tissue homogenates.

Clinical assessment of K/BxN serum induced arthritis

Clinical parameters of arthritic mice were assessed starting on day 0 up to day 23 after arthritis induction. Clinical scoring for arthritis was performed using a 0–4 AI scale, where 0 = no swelling or erythema, 1 = slight swelling and/or erythema, 2 = low-to-moderate edema, 3 = pronounced edema with limited use of the joint, and 4 = excessive edema with joint rigidity. Ankle circumferences were determined as previously described for rat AIA (22). Two perpendicular diameters of the joint were measured with a caliper (Lange Caliper; Cambridge Scientific Industries, Cambridge, MA, USA), and ankle circumference was determined by using the geometric formula: circumference = 2 π (√(a2 + b2/2)), where a is the laterolateral diameter, and b is the anteroposterior diameter. Mean circumferences of all ankle joints (4 per mouse) were averaged. Data are depicted as an increase in joint circumference with ankle thickness on day 0 (before serum injection) considered as the baseline value. All measurements were taken by observers blinded to the experimental conditions.

Determination of Hb concentrations in K/BxN ankle homogenates

For Hb analysis, mouse joints were homogenized as described previously (23). Hb levels were measured by adding 25µl of homogenate mixed with 25µl of 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) reagent to 96-well plates. Samples incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes. Absorbance was read with a Microplate Manager ELISA reader at 450nm. Hb concentration was determined by comparison with a standard curve in mg/ml. These values were normalized by dividing the Hb concentration by the amount of total protein (mg/ml) in the homogenate. Hb concentration is a reflection of the number of blood vessels in the tissue (18).

HMVEC and EPC migration to engrafted tissue in the ST SCID mouse chimera

SCID mice were grafted as described previously (12). We utilized the normal (NL) and RA ST SCID mouse chimeras to evaluate HMVEC and EPC trafficking from the PB to engrafted ST. Once grafts took, fluorescently dye-tagged (PKH26 dye) HMVECs or EPCs were injected i.v. into mice engrafted with either NL or RA ST. ECs were allowed to circulate for at least 48 (for HMVECs) to 72 (for EPCs) hours. The different incubation times for HMVECs and EPCs reflects the speed of incorporation of HMVECs compared to EPCs, as we found that mature HMVECs are recruited and integrated into the vasculature of engrafted synovium faster than EPCs.

mRNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

SCID mice grafts were snap-frozen and prepared for mRNA analysis. Total RNA was isolated from snap-frozen tissue using RNAeasy mini RNA isolation kits in conjunction with QIAshredders (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Following isolation, RNA was quantified and checked for purity using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). cDNA was then prepared using a Verso cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The primers used for human CXCL16 and GAPDH were the same as used previously (12). All samples were run in duplicate and using Eppendorf software.

Results

CXCR6 expression on ECs

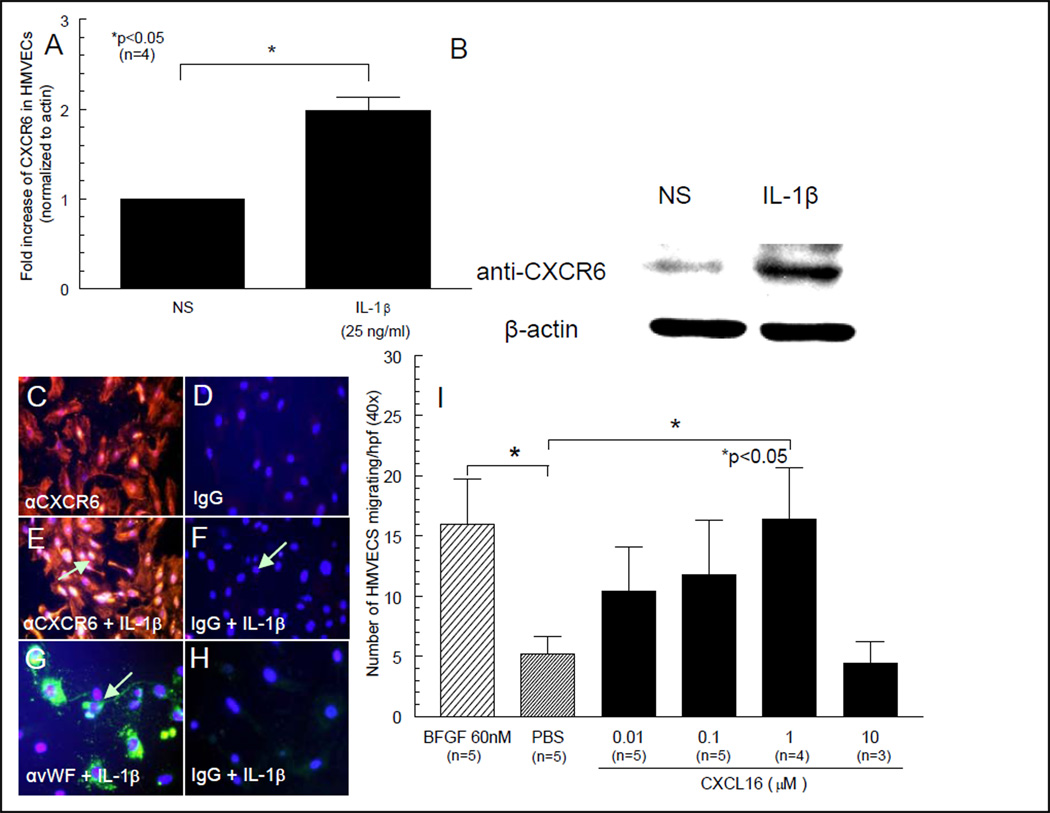

We show by Western blotting that HMVECs express CXCR6 and that CXCR6 can be upregulated by IL-1β (figures 1A and B). For immunofluorescence staining, anti-human CXCR6 was used as primary antibody for detection of CXCR6 expression on HMVECs (figure 1C) or human EPCs (figure 3A) respectively. We show that HMVECs express CXCR6 that is inducible with IL-1β (figures 1C and D). Control IgG staining is shown in figures 1D, F and H and control staining for EC specific vWF is shown in figure 1G. CXCR6 is also expressed on EPCs (figures 3A, C and D).

Figure 1. HMVECs express CXCR6 and are chemotactic for CXCL16.

We show by Western blotting that HMVECs express CXCR6 and can be upregulated by IL-1β (figures 1A and B). C) HMVEC expression of CXCR6 is shown by red fluorescence staining. D) Control IgG staining for HMVECs is also shown. E) Intense HMVEC CXCR6 staining in response to rhuIL-1β stimulation is clearly seen, showing that CXCR6 is inducible in ECs (see arrow). F) Control IgG staining in response to rhIL-1β stimulation does not show EC staining for CXCR6. G) HMVEC vWF staining in response to rhIL-1β stimulation is apparent. H) Control IgG staining for IL-1β induced vWF (all images 40X). I) HMVECs migrate towards CXCL16 in a dose-dependent manner. HMVECs are chemotactic for CXCL16 at 1µM, indicating CXCL16 functions as an EC chemotactic factor.

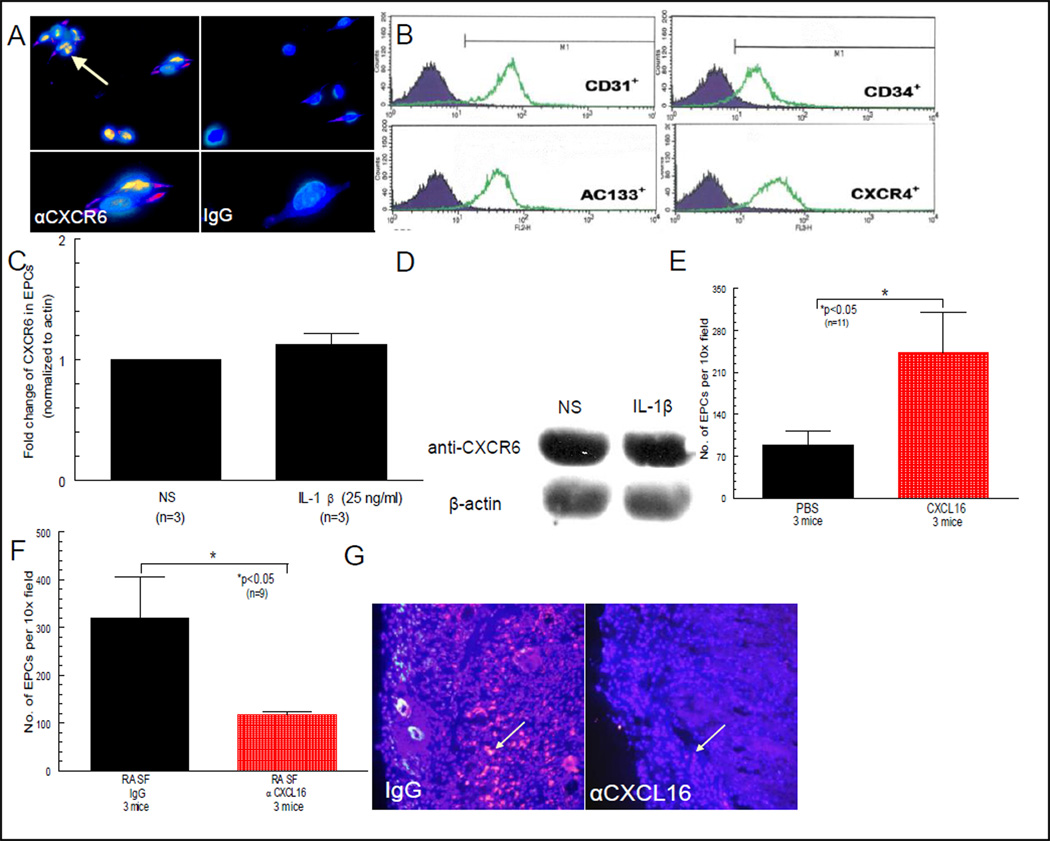

Figure 3. EPCs express CXCR6 and migrate to CXCL16 in vivo.

A) EPC expression of CXCR6 is shown by yellow/orange fluorescence staining (see beige arrow, 40X). B) EPCs express CD31 and can also be identified and sorted by CD34 expression, and found that >95% of these cells are AC133+ cells. The isolated cell population also expressed CXCR4, the receptor for SDF-1α/CXCL12, even without any external stimuli (e.g. cytokines, LPS, PMA, etc.). C and D) CXCR6 can be shown by Western blotting to be strongly expressed on EPCs, but not upregulated by IL-1β. E) SCID mice were engrafted with NL human synovium. Mice receiving intragraft injections of CXCL16 had approximately a 3 fold increase in EPC infiltration to engrafted tissue compared to mice receiving intragraft injections of PBS (n = no. of sections counted from 3 separate mice per group; 10X). F and G) NL synovium was engrafted into SCID mice and allowed several weeks to take. Mice injected with sham immunoneutralized RA SF showed robust recruitment of fluorescently dye-tagged EPCs, compared to mice injected with RA SF treated with anti-CXCL16 (see arrows; n = no. of sections evaluated from 3 different mice per group; 10X).

CXCL16 induces HMVEC chemotaxis

We tested the ability of CXCL16 to induce HMVEC migration in vitro. CXCL16 HMVEC chemotactic activity peaked at 1µM CXCL16 and fell off thereafter (figure 1I). The experiment was performed at least 3 times. Data are expressed as the number of cells migrating per well.

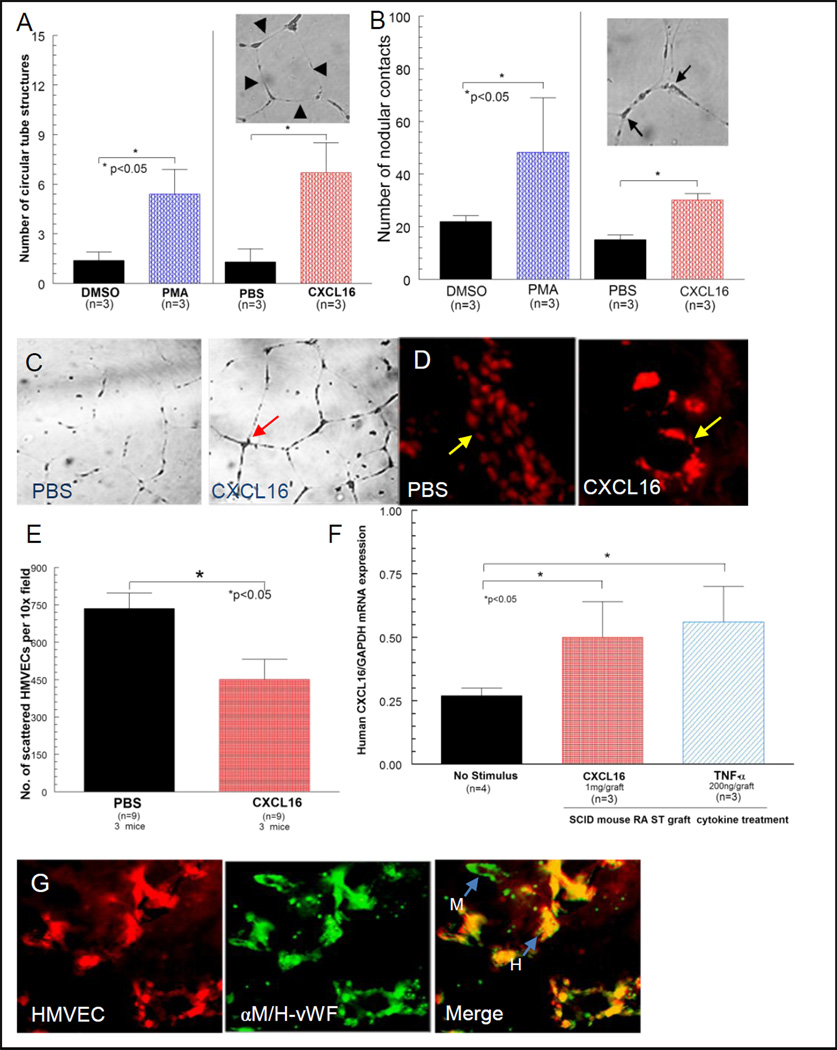

In vitro capillary morphogenesis assay shows that CXCL16 is angiogenic in vitro

Capillary tube formation was determined blindly by evaluating nodular contacts between at least 3 endothelial cell tubes, and the number of circular tube network formations was counted. Note that CXCL16 induced tube formation (see arrows), consistent with the chemotaxis results (figures 2A, B and C). Data are expressed as the absolute number of events in response to CXCL16. The assay was performed three times in triplicate. Data are expressed as the absolute number of events in response to CXCL16.

Figure 2. CXCL16 forms tubes in Matrigel and in the human ST SCID mouse chimera.

A, B and C) Capillary tube formation was determined blindly by evaluating circular tube networks and nodular contacts between at least 3 endothelial cell tubes. D) The left panel shows a representative NL ST section with scattered dye-tagged HMVECs migrating in response to PBS (see arrow in D). In the right panel, clearly organized migration of dye-tagged HMVECs is shown in response to intragraft administration of CXCL16 (40X). E) Fewer scattered HMVECs are observed in the RA ST SCID mouse chimera to CXCL16, likely due to HMVEC clumping. F) Intragraft injections of CXCL16 or TNF-α induced expression of CXCL16 mRNA in engrafted RA ST (n=number of mice). G) The far left panel shows a serial section of PKH26 dye-tagged HMVECs migrating into engrafted human ST. The middle panel shows a serial section taken from the same tissue stained with FITC labeled rabbit anti-human/mouse vWF (factor VIII). The right panel is a merger of panels. The green color shows mouse endothelium (arrow pointed at “M”), whereas the yellow color identifies human endothelium (arrow pointed at “H”) demonstrating the formation of a true chimera (40X).

HMVEC and EPC migration to engrafted tissue in the ST SCID mouse chimeras is due to CXCL16

Fewer scattered HMVECs appear to migrate towards CXCL16 in both the NL ST (figure 2D) and RA ST (figure 2E) SCID mouse chimeras. This can be explained by the finding of clumps of HMVECs apparently forming vasculature, thus having fewer scattered cells (figure 2D). We also found that TNF-α as well as CXCL16 upregulate CXCL16 expression in vivo. SCID mice grafts were snap-frozen and prepared for mRNA analysis, and as shown in figure 2F, both TNF-α and CXCL16 upregulate CXCL16 mRNA expression in the RA ST SCID mouse chimera system. Shown in figure 2G are merged images of HMVECs migrating into RA ST in the RA ST SCID mouse chimera. The first panel is red fluorescent HMVECs. The second panel is ST stained for both anti-mouse/human vWF (stains all ECs). The final panel is a merged image of the first two, showing mouse (green) and human (yellow) integrated into the developing vasculature, indicating the formation of a true vascular chimera.

Human CD34+ EPCs can be isolated and characterized from cord blood

Central to all of these studies is our ability to generate pure populations of human EPCs. Cells were sorted and purified as shown in figure 3B, and we confirmed that pure populations of cells could be successfully isolated by receptor expression. We also show by Western blotting that CXCR6 is highly expressed on EPCs but unlike HMVECs, is not upregulated by IL-1β (figures 3C and D). EPCs also migrate towards the chemotactic stimulus (i.e. CXCL16) as more fluorescently dye-tagged cells were found in the NL ST graft (figure 3E), not appearing to form clumps characteristic of HMVECs. Human cord blood preparations typically yield 1.5 to 2x106 CD133+ EPCs per preparation, with purities in excess of 95%.

EPC migration to engrafted tissue injected with RA SF depleted of CXCL16

Injecting RA SF allows for neutralization studies as a single chemokine can be neutralized from the RA SF before injection, for examination of its singular role in cellular recruitment and integration into the implanted tissue. Mice engrafted with NL ST receiving intragraft injections of RA SF depleted of CXCL16 (CXCL16 and sham neutralized RA SFs diluted 1:300 in PBS; injected intragraft 100µl/graft) showed a robust reduction of EPC migration compared to the sham depleted control group (figures 3F and G). This indicates that CXCL16 contained within the RA SF is directly responsible, in part, for EPC migration into NL human synovium (n=9 tissue sections from 3 different mice per group).

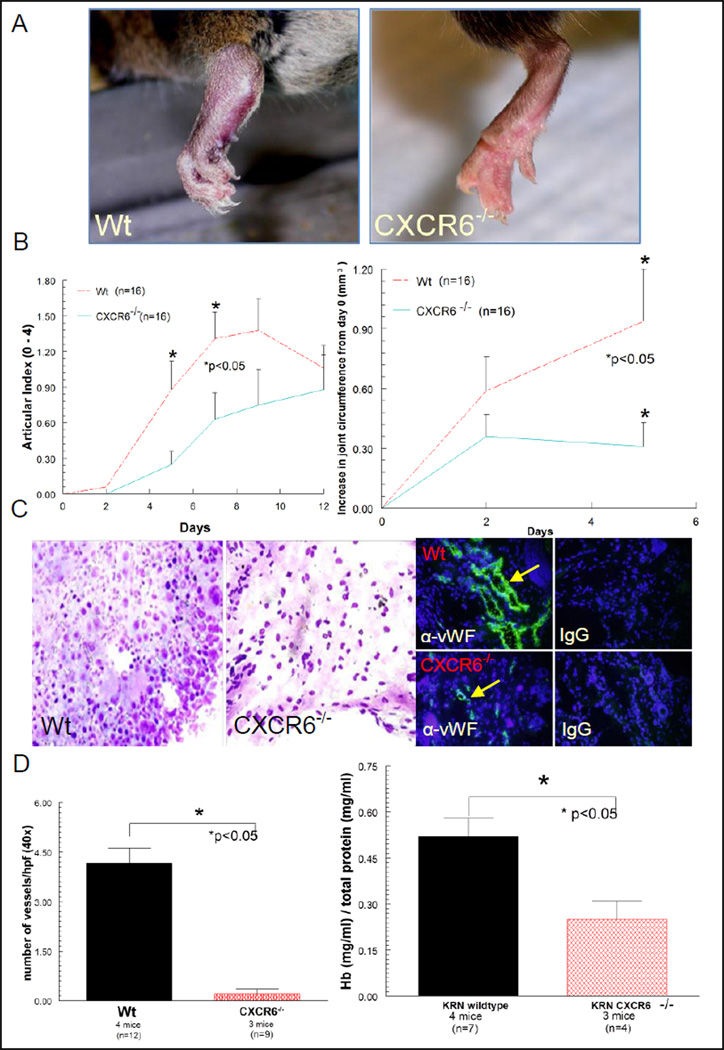

CXCR6−/− deficiency results in reduced joint swelling, pathology and vasculature following induction of K/BxN serum induced arthritis compared to Wt mice

Day 9 Wt K/BxN serum induced mice showed severe redness and swelling of joints, whereas CXCR6−/− mice did not (figure 4A). In addition, CXCR6−/− mice had statistically significant reductions in AI and joint swelling compared to Wt mice on day 5 (figure 4B). Mouse joint tissue sectioned from Wt and CXCR6−/− K/BxN serum induced arthritic mice were hematoxylin and eosin stained in order to evaluate joint pathology. As shown in figure 4C, day 9 K/BxN serum induced Wt mice show a significant enhancement of cellular infiltrate compared to K/BxN serum induced CXCR6−/− mice. We also evaluated the number of vessels from the same tissues identified by von Willebrand factor (vWF) expression using fluorescence immunohistology. We show that K/BxN mice lacking CXCR6 have a profound reduction in blood vessels (figures 4C and 4D). To validate these findings, we measured Hb concentrations, a measure of total joint vascularity, from joint homogenates taken from the same animals as described previously (18, 23). CXCR6−/− K/BxN serum induced arthritic mice had significantly less Hb (normalized to respective total protein) compared to arthritic Wt mice (figure 4D), confirming the histological findings of reduced vascularity in arthritic CXCR6−/− mouse joints.

Figure 4. CXCR6 deficiency reduces joint inflammation and vascularity in K/BxN serum induced arthritis.

A) Representative clinical images of inflamed joints revealed significant edema and inflammation in Wt, but not CXCR6−/− mice following arthritis induction with K/BxN serum. B) Mice lacking CXCR6 have significantly lower AI scores compared to Wt mice on days 5 and 7 of K/BxN serum induced arthritis [4 mice (16 joints) per group ± SEM]. Absolute increases in joint circumference after arthritis induction showed significantly less joint swelling in day 5 CXCR6−/− compared to Wt mice (p<0.05). C) In the left panel, joint histology of K/BxN serum induced day 9 Wt mice showed increased cellular infiltrate and severe tissue damage compared to CXCR6−/− mice (hematoxylin and eosin stain; 5µm, 40X). In the right panel, reduced vascular staining is also clearly seen in CXCR6−/− compared to Wt mice by immunofluorescence staining. D) The left graph shows the reduction in the number of blood vessels in CXCR6−/− joint tissue from the same mice (n corresponds to the number of tissue sections counted). Joint homogenates show significantly less Hb (normalized to total protein concentrations) in day 9 K/BxN serum induced CXCR6−/− compared to similarly treated Wt mice (right graph).

Western blotting shows that CXCR6 regulation and CXCL16 signaling pathways in HMVECs and EPCs are different

We have successfully utilized Western blotting to show that CXCL16 upregulates HMVEC *pP38, *pErk½ and *pJnk, in a time dependent manner (figures 5A, B and C), whereas *pSrc was downregulated by CXCL16 (figure 5D). We also show that EPCs signal through *pP38 (figure 5E) and *pSrc (figure 5F) in response to CXCL16. The signaling results are summarized in the table (figure 5G). The upper band for each respective blot shows the phosphorylated (*p) signaling molecule only. The lower band shows the total (T) amount of the signaling molecule containing phosphorylated (*p) and unphosphoylated forms of each molecule. Therefore, the upper blot is an indication of the amount of phosphorylated protein contained in the lower band for each signaling molecule. All *p blots (upper panel of bands) were normalized to blots of total P38, Erk½, Jnk, or Src (lower panel of bands) for all respective blots; representative blots from n=3 separate blots are shown above graphs).

Figure 5. Signaling data shows HMVECs and EPCs are activated by CXCL16.

Blots A, B, C and D show the signaling of CXCL16 in HMVECs. Blots E and F show signaling in EPCs. The upper band for each respective blot show the phosphorylated signaling molecule only. The lower band shows the total (T) amount of the signaling molecule containing phosphorylated (*p) and unphosphoylated forms of each molecule. Therefore, the upper blot is an indication of the amount of phosphorylated protein contained in the lower band for each signaling molecule. As shown, HMVEC *pP38, *pErk½ and *pJnk are activated by CXCL16, whereas *pSrc is downregulated. With respect to EPCs, *pP38 (E) and *pSrc (F) are activated in response to CXCL16. The table (G) lists all the signaling data for HMVECs and EPCs to CXCL16. Most interesting is the finding that both cell types signal through *pP38, indicating that CXCL16 angiogenic and/or vasculogenic activity can be targeted by *pP38 inhibition. All *p blots (upper panel of bands) were normalized to blots of total P38, Erk½, Jnk, or Src (lower panel of bands) for all respective blots; representative blots from n=3 separate blots are shown above graphs).

CXCR6−/− deficiency results in reduced leukocyte recruitment following induction of K/BxN serum induced arthritis when compared to Wt mice

Figure 6A (Wt mice) shows prominent CD3+ and CD14+ expression in Wt K/BxN serum induced mouse joints with the negative IgG control staining shown. We found profound reductions in both CD3+ (figure 6B) and CD14+ (figure 6C) expression in K/BxN serum induced mice lacking CXCR6.

Figure 6. CXCR6−/− deficiency results in reduced leukocyte recruitment to inflamed joint tissue.

Joints from day 9 CXCR6−/− and Wt mice induced with K/BxN serum were harvested and stained for CD3+ and CD14+ expression by immunofluorescence histology. A) Upper panel (Wt) shows prominent CD3+ and CD14+ expression in Wt K/BxN serum induced mice with the negative IgG control staining shown. In the lower panel (CXCR6−/−) of figure 6A, we found profound reductions in both CD3+ and CD14+ expressing cells in K/BxN serum induced mice lacking CXCR6 with the negative IgG control staining shown. The number of CD3+ (figure 6B) and CD14+ (figure 6C) expressing cells was significantly reduced in joints of arthritic mice deficient in CXCR6 (n = number of fields counted per mouse tissue section; taken from at least 3 different mice). Leukocyte recruitment was quantified by counting the number of fluorescing cells in a 40X field.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed using a student’s t-test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Discussion

RA is a debilitating inflammatory joint disease in which microvascular expansion in the joint lining (synovium) is a characteristic finding. Synovial neovascularization occurs presymptomatically, and is critical for disease progression (24). Studies in rodents have shown that inhibition of angiogenesis results in suppression of arthritis as well (25), however, there is limited data to quantitate the effectiveness of therapies targeted to potent angiogenic chemokines or chemokine receptors. Notably, RA patients show increased numbers of circulating EPCs that correlate with Disease Activity Scores using 28 joint counts (DAS28), signifying that EPCs are likely elevated and recruited to inflamed tissues for the purposes of synovial vasculogenesis (26). Previous studies showed that mice depleted of CXCL16 have reduced arthritis severity (27), and suggest that CXCR6 and its ligand CXCL16 may be important mediators of arthritis development. We believe that CXCL16 is central to this process because of the expression of CXCR6 on HMVECs and EPCs, and the highly elevated expression of CXCL16 in RA SF (12). Using a combined in vitro and in vivo approach, we examined possible environmental cues that might direct the migration, differentiation, and functional incorporation of HMVECs and EPCs into the microcirculatory system. Initially, we immunostained HMVECs and EPCs to validate their expression of CXCR6, and confirmed that we could upregulate HMVEC CXCR6 expression in response to a pro-inflammatory stimulus. Next, we examined the ability of CXCL16 to recruit HMVECs and form tubes in vitro. We found that HMVECs migrate to CXCL16 dose-dependently, using a modified Boyden chemotaxis system. We then showed that HMVECs respond to CXCL16 in Matrigel by forming tubes, in agreement with our chemotaxis findings.

To examine HMVEC behavior to CXCL16 in vivo, we injected CXCL16 intragraft into NL ST SCID mouse chimeras and found that well integrated HMVECs could be found in the engrafted synovium 48 hours post-injection, not as scattered cells, but as clumps of cells that appear to be forming vessels and chimeric nodes with the surrounding murine vasculature. EPCs also migrated in the SCID mouse chimera system, and we showed that by depleting RA SF of CXCL16, we could suppress EPC recruitment by approximately two thirds, confirming that CXCL16 contained within RA SF induces EPC migration from the peripheral blood directly into engrafted human ST. We also defined the signaling pathways for both types of ECs to CXCL16, and found interesting divergences between the mature phenotype (HMVECs) and EPCs. We found that both HMVECs and EPCs upregulate *pP38 expression in response to CXCL16, whereas *pSrc expression was upregulated in EPCs, but downregulated in HMVECs. In addition, HMVECs signaled in response to CXCL16 via *pErk½ and *pJnk, whereas EPCs did not. We surmised that ECs may signal differently to CXCL16 based primarily upon the maturity of the cell.

Although we found that HMVECs and EPCs readily migrated in the SCID mouse chimera, HMVECs integrated into the established vasculature at a much faster pace compared to EPCs, reminiscent of an angiogenic response. Conversely, EPCs appear to home much like mononuclear cells (12), and do not incorporate into existing vasculature as quickly, resembling a more vasculogenic response. These findings suggest that CXCL16 is a robust agonist of both angiogenesis (HMVEC migration and incorporation) and vasculogenesis (EPC migration), promoting both de novo blood vessel formation in RA synovium and expansion of the existing capillary network by two independent mechanisms. We found that CXCL16 as well as TNF-α upregulated CXCL16 mRNA expression in the SCID mouse chimera, defining an amplification step for the expression of CXCL16 in vivo. As a result of these findings, it is tempting to speculate that by inhibiting EC CXCL16 signaling via *pP38, both the angiogenic and vasculogenic processes stimulated by CXCL16 could be disrupted, perhaps identifying a legitimate target for inhibiting CXCL16 induced EC activity within the RA joint.

We further validated our findings by injecting K/BxN serum into CXCR6−/− mice. Our studies showed that mice lacking CXCR6 (obtained as a kind gift from Dr. Daniel R. Littman at New York University) have attenuated arthritis development compared to Wt mice. Indeed, while Wt mice clearly displayed a robust inflammatory phenotype including functional deficits following arthritis induction; their CXCR6−/− counterparts were comparatively only mildly affected, suggesting that CXCR6 is a critical mediator of arthritis development. This was supported by histologic findings showing that CXCR6−/− mice have a reduced inflammatory profile in their joint tissues in response to K/BxN serum. We also show that K/BxN treated CXCR6−/− mice have reduced Hb content in their joint homogenates, as well as profound reductions in vWF (EC marker), CD3 (T-cell marker) and CD14 (macrophage marker) expressing cells in joint tissues compared to similarly treated age and weight matched Wt mice.

It should be stated that CXCL16 can recruit other cells apart from ECs that may produce angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF). Indeed, our data demonstrates that CXCR6 deficiency results in profound reductions in monocytes known to produce VEGF. However, our data strongly argues for a direct role of CXCL16 to stimulate angiogenic activity including HMVEC chemotaxis and tube formation in Matrigel, both performed absent of other cell types. Although HMVECs are also capable of producing VEGF that may potentially confound our findings, it is important to point out that our controls using only PBS did not show substantial angiogenic activity in either the HMVEC migration or tube forming assays. We then confirmed these findings in vivo using both HMVECs and EPCs (both shown to express CXCR6, the only known CXCL16 receptor). These findings, when considered in total, lead us to the conclusion that CXCL16 functions as both an angiogenic mediator and potent leukocyte recruitment factor.

Because our findings show that CXCL16 is involved in blood vessel formation in arthritic joints, it is possible that the CXCL16-CXCR6 pathway may be a premiere pathway in the recruitment of EPCs from the bone marrow. This is supported by findings of very high percentages (>90%) of mesenchymal stem cells from both humans and mice shown to express CXCR6 (11). In agreement, we show that EPCs and HMVECs prominently express CXCR6, which might explain the significant reductions in vascularitiy in CXCR6−/− mice during arthritis development. Interestingly, we also discovered that HMVECs and EPCs regulate the expression of CXCR6 differently when stimulated with IL-1β, with HMVECs, but not EPCs, rapidly upregulating CXCR6 in response to IL-1β. Notably, we found that EPCs show robust expression of CXCR6 without a need for further stimulation. It is tempting to speculate that EPCs may require this receptor to navigate from the bone marrow to inflamed tissues such as the RA joint.

In lieu of our findings, it has been argued that EPCs may not be a viable target for RA therapy as these cells have not been found in appreciable numbers in inflamed synovium. However, these same findings also raised concerns as to whether the same EPC population is truly being monitored in vivo, and has imposed tremendous limitations on the assessment of the biological function of EPCs as well as their potential use as a therapeutic target (28). In support of a pro-inflammatory role for EPCs, it was previously demonstrated that human EPCs readily migrate to RA ST, compared to NL ST, in the SCID mouse chimera (14), and these findings are in complete agreement with our study using a similar chimera model system. Our most significant findings show that EPCs migrate toward RA SF in vivo, and that this effect can be abrogated with the removal of CXCL16. We also show that the EC signaling pathways to CXCL16 are different depending upon the maturity of ECs, and have indicated where the different pathways intersect that may be suitable targets for intervention strategies. Overall, we provide further evidence that CXCL16 is a central pro-inflammatory chemokine in the RA joint, promoting both vasculogenesis and angiogenesis and contributing to the expansion of the neovasculature in the RA synovium.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the pilot project of the University of Michigan Rheumatic Diseases Research Core Center (P30AR048310), and NIH grants AI40987, HL58694, AR48267, R01CA122031 and an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship grant AHA0423758Z. Additional support included the Frederick G.L. Huetwell and William D. Robinson, M.D. Professorship in Rheumatology. This work was also supported in part by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

Author’s contributions

TI performed the signaling and fluorescent staining studies, and CSH performed the in vitro angiogenesis studies. JHR, MAA and MDA performed the K/BxN and in vivo studies. ASA provided EPCs and assisted in the design of experiments using EPCs. AEK assisted with the design of the study and editing of the manuscript. JHR conceived and designed all aspects of the study and drafted the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Firestein GS. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2003;423(6937):356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature01661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corrigall VM, Panayi GS. Autoantigens and immune pathways in rheumatoid arthritis. Crit Rev Immunol. 2002;22(4):281–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paleolog EM. Angiogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2002;4(Suppl 3):S81–S90. doi: 10.1186/ar575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folkman J, Haudenschild C. Angiogenesis by capillary endothelial cells in culture. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1980;100(3):346–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masuda H, Asahara T. Post-natal endothelial progenitor cells for neovascularization in tissue regeneration. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58(2):390–398. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00785-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas CS, Amin MA, Ruth JH, Allen BL, Ahmed S, Pakozdi A, et al. In vivo inhibition of angiogenesis by interleukin-13 gene therapy in a rat model of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(8):2535–2548. doi: 10.1002/art.22823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volin MV, Woods JM, Amin MA, Connors MA, Harlow LA, Koch AE. Fractalkine: a novel angiogenic chemokine in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(4):1521–1530. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62537-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koch AE, Polverini PJ, Kunkel SL, Harlow LA, DiPietro LA, Elner VM, et al. Interleukin-8 as a macrophage-derived mediator of angiogenesis. Science. 1992;258(5089):1798–1801. doi: 10.1126/science.1281554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szekanecz Z, Koch AE. Angiogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. In: Hochberg M, editor. Rheumatology. 4th ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szekanecz Z, Koch AE. Chemokines and angiogenesis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13(3):202–208. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamberlain G, Wright K, Rot A, Ashton B, Middleton J. Murine mesenchymal stem cells exhibit a restricted repertoire of functional chemokine receptors: comparison with human. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(8):e2934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruth JH, Haas CS, Park CC, Amin MA, Martinez RJ, Haines GK, 3rd, et al. CXCL16-mediated cell recruitment to rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue and murine lymph nodes is dependent upon the MAPK pathway. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(3):765–778. doi: 10.1002/art.21662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Distler JH, Beyer C, Schett G, Luscher TF, Gay S, Distler O. Endothelial progenitor cells: novel players in the pathogenesis of rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(11):3168–3179. doi: 10.1002/art.24921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverman MD, Haas CS, Rad AM, Arbab AS, Koch AE. The role of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1/ very late activation antigen 4 in endothelial progenitor cell recruitment to rheumatoid arthritis synovium. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(6):1817–1826. doi: 10.1002/art.22706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore XL, Lu J, Sun L, Zhu CJ, Tan P, Wong MC. Endothelial progenitor cells' "homing" specificity to brain tumors. Gene therapy. 2004;11(10):811–818. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katschke KJ, Jr, Rottman JB, Ruth JH, Qin S, Wu L, LaRosa G, et al. Differential expression of chemokine receptors on peripheral blood, synovial fluid, and synovial tissue monocytes/macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(5):1022–1032. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1022::AID-ANR181>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruth JH, Rottman JB, Katschke KJJ, Qin S, Wu L, LaRosa G, et al. Selective lymphocyte chemokine receptor expression in the rheumatoid joint. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(12):2750–2760. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2750::aid-art462>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park CC, Morel JC, Amin MA, Connors MA, Harlow LA, Koch AE. Evidence of IL-18 as a novel angiogenic mediator. J Immunol. 2001;167(3):1644–1653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar P, Hosaka S, Koch AE. Soluble E-selectin induces monocyte chemotaxis through Src family tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21039–21045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruth JH, Volin MV, Haines GK, 3rd, Woodruff DC, Katschke KJ, Jr, Woods JM, et al. Fractalkine, a novel chemokine in rheumatoid arthritis and in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(7):1568–1581. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200107)44:7<1568::AID-ART280>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monach P, Hattori K, Huang H, Hyatt E, Morse J, Nguyen L, et al. The K/BxN mouse model of inflammatory arthritis: theory and practice. Methods Mol Med. 2007;136:269–282. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-402-5_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woods JM, Katschke KJ, Volin MV, Ruth JH, Woodruff DC, Amin MA, et al. IL-4 adenoviral gene therapy reduces inflammation, proinflammatory cytokines, vascularization, and bony destruction in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2001;166(2):1214–1222. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruth JH, Amin MA, Woods JM, He X, Samuel S, Yi N, et al. Accelerated development of arthritis in mice lacking endothelial selectins. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(5):R959–R970. doi: 10.1186/ar1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koch AE. Angiogenesis as a target in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(Suppl 2):ii60–ii67. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.suppl_2.ii60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peacock DJ, Banquerigo ML, Brahn E. Angiogenesis inhibition suppresses collagen arthritis. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1135–1138. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jodon de Villeroche V, Avouac J, Ponceau A, Ruiz B, Kahan A, Boileau C, et al. Enhanced late-outgrowth circulating endothelial progenitor cell levels in rheumatoid arthritis and correlation with disease activity. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(1):R27. doi: 10.1186/ar2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nanki T, Shimaoka T, Hayashida K, Taniguchi K, Yonehara S, Miyasaka N. Pathogenic role of the CXCL16-CXCR6 pathway in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(10):3004–3014. doi: 10.1002/art.21301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mellick AS, Plummer PN, Nolan DJ, Gao D, Bambino K, Hahn M, et al. Using the transcription factor inhibitor of DNA binding 1 to selectively target endothelial progenitor cells offers novel strategies to inhibit tumor angiogenesis and growth. Cancer Res. 2010;70(18):7273–7282. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]