Abstract

Toxoplasma gondii is well-known to subvert normal immune responses, however, mechanisms are incompletely understood. In particular, its capacity to alter receptor-activated Ca2+-mediated signaling processes has not been well-characterized. In initial experiments, we found evidence that T. gondii infection inhibits Ca2+ responses to fMetLeuPhe in murine macrophages. To further characterize the mechanism of inhibition of Ca2+ mobilization by T. gondii, we used the well-studied RBL mast cell model to probe the capacity of T. gondii to modulate IgE receptor-activated signaling within the first hour of infection. Ca2+ mobilization that occurs via IgE/FcεRI signaling leads to granule exocytosis in mast cells. We found that T. gondii inhibits antigen-stimulated degranulation in infected cells in a strain-independent manner. Under these conditions, we found that cytoplasmic Ca2+ mobilization, particularly antigen-mediated Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, is significantly reduced. Furthermore, stimulation-dependent activation of Syk kinase leading to tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of phospholipase Cγ is inhibited by infection. Therefore, we conclude that inhibitory effects of infection are likely due to parasite-mediated inhibition of the tyrosine kinase signaling cascade that results in reduced hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Interestingly, inhibition of IgE/FcεRI signaling persists when tachyzoite invasion is arrested via cytochalasin D treatment, suggesting inhibition is mediated by a parasite-derived factor secreted into the cells during the invasion process. Our study provides direct evidence that immune subversion by T. gondii is initiated concurrently with invasion.

Keywords: IgE, FcεRI, Syk kinase

Introduction

The apicomplexan T. gondii has evolved to be an extremely successful obligate intracellular parasite. It parasitizes a multitude of mammalian and avian species as intermediate hosts. In felines, which serve as the definitive host, sexual reproduction results in shedding of highly infectious oocysts. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention estimates one fifth of the US. human population is latently infected with T. gondii. In most hosts, infection is long-lived but asymptomatic. Nevertheless, under certain conditions, such as in immuno-compromised individuals, acute toxoplasmosis poses serious health risks (Dubey, 1998).

T. gondii infects host cells through a process of active invasion and establishment of a parasitophorous vacuole that resists fusion with the phago-lysosomal system (Sibley, 2004). One of the probable reasons for the success of Toxoplasma as an intracellular pathogen is its development of immuno-modulatory mechanisms to evade and control the host response to infection (Laliberte and Carruthers, 2008; Leng et al., 2009a). In vivo infection results in a strong IFN-γ-mediated protective immune response that is necessary for host survival, and, as a result, for parasite survival (Lambert and Barragan, 2010). At the same time, infection actively suppresses production of many pro-inflammatory cytokines (Leng et al., 2009a). Virulence factors such as ROP16 and ROP18 are secreted from parasite rhoptries and act to directly modulate host cell signaling and interfere with host antimicrobial function (Butcher et al., 2005; Saeij et al., 2006; Taylor et al., 2006; Yamamoto et al., 2009, 2011). Ca2+ mobilization is a key regulator of many signaling pathways in immune cells, including those that control granule exocytosis, chemotaxis, and gene transcription and expression (Putney, 2009). A recent study demonstrated Toxoplasma alteration of Ca2+ signaling in neurons during chronic infections (Haroon et al., 2012). Studies of T. gondii invasion in the context of a well-established immune model in which Ca2+ signaling triggers a rapid response, such as mast cell degranulation, are useful to understand mechanisms by which Toxoplasma can modulate Ca2+ signaling.

While there is evidence that peritoneal mast cells mount an immune response to Toxoplasma infection (Ferreira et al., 2004; Sawesi et al., 2010), mast cells have not been determined to be reservoirs for T. gondii in vivo. However, other immune cell types, such as macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils, are known targets of T. gondii infection (Bierly et al., 2008; Lambert and Barragan, 2010). In all of these cell types, Ca2+-dependent signaling is involved in crucial cellular functions. For example, Ca2+-mediated signaling pathways are involved in FcRγ-mediated phagocytosis, inflammation, and nitric oxide synthesis in macrophages (Jongstra-Bilen et al., 2008; Braun et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2012), and C-type lectin signaling in dendritic cells relies on phospholipase C (PLC)γ2 (Xu et al., 2009). In response to N-formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl-L-phenylalanine (fMLP), Ca2+ mobilization by neutrophils is activated via PLCβ (Andersson et al., 1986; Ferretti et al., 2001).

Mast cells express FcεRI, the high affinity receptor for IgE, and they are primary mediators of the allergic response (Metcalfe et al., 1997). Crosslinking of IgE-FcεRI complexes on the cell surface by oligovalent antigen is the first step in the cascade of signaling events that results in the exocytosis of preformed mediators, such as histamine and serine proteases, with a time course of minutes (Metcalfe et al., 1997). FcεRI belongs to the family of multichain immune recognition receptors (MIRRs) that also include B-cell and T-cell receptors (Cambier, 1995). Signal transduction through FcεRI has been extensively studied by us and others (Holowka et al., 2005; Rivera and Gilfillan, 2006) and involves PLCγ1 and PLCγ2 activation leading to Ca2+ mobilization and protein kinase C (PKC) activation, both of which are necessary for stimulated granule exocytosis (Ma and Beaven, 2009; Holowka et al., 2012).

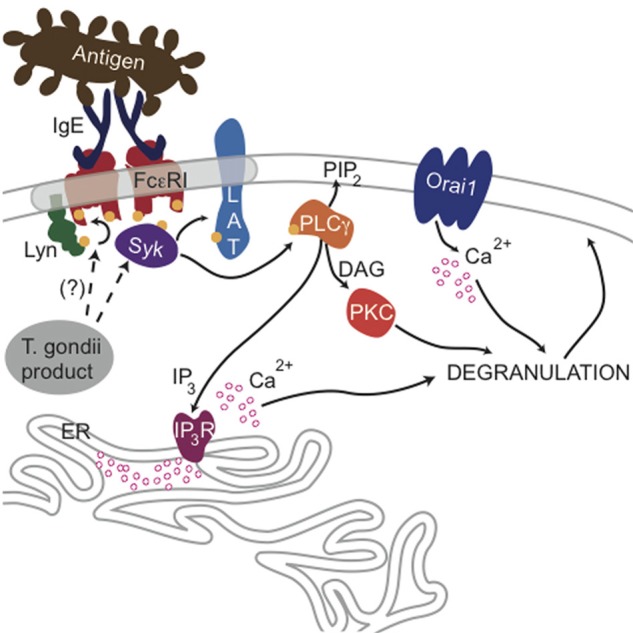

In the present study we demonstrate that Ca2+ responses are altered in Toxoplasma-infected primary neutrophils, and we utilize the well-established RBL mast cell model system to characterize the mechanism by which Toxoplasma rapidly modulates Ca2+-mediated immune cell signaling. We find that, within an hour of infection, parasites significantly inhibit antigen-mediated degranulation, primarily by inhibition of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)-dependent Ca2+ mobilization. Additional experiments revealed that PLCγ activation by Syk tyrosine kinase is inhibited by Toxoplasma infection. Finally, we found that inhibition of degranulation prevails under conditions in which inhibition of actin polymerization prevents parasite invasion. Collectively, these results support a model in which T. gondii inhibits FcεRI receptor signaling during invasion by releasing a factor that inhibits Syk mediated activation of PLCγ, and thus interferes with hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to produce the second messengers IP3 and diacylglycerol (DAG) important for Ca2+ mobilization and degranulation.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Indo-1-AM and Fluo-4-AM were purchased from Invitrogen Corp. 4-methylumbelliferyl-N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide, cytochalasin D, FITC-dextran, and thapsigargin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Unless otherwise noted, all other tissue culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen, and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-DNP IgE was purified as described previously (Posner et al., 1992). Multivalent antigen, DNP-BSA, was prepared as described previously (Weetall et al., 1993).

Cells and parasites

RBL-2H3 mast cells

RBL-2H3 mast cells were maintained in monolayer culture through weekly passage as described previously (Gidwani et al., 2003). For stimulation, cells were sensitized with 1 μg/ml anti-DNP IgE for 4–24 h.

Mouse neutrophils

Female C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks of age) were purchased from either The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) or Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY) and were maintained in the Transgenic Mouse Core Facility at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, accredited by American Association of Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Mouse neutrophils were isolated by percoll gradient purification as described previously (Abi Abdallah et al., 2011).

The experiments in this study were performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Cornell University (permit number 1995-0057). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering during the course of these studies.

Parasites

RH, PTG, CTG, Veg, and RH-tomato strains of parasites were used in this study. The RH-tomato strain, stably expressing tomato fluorescent protein, was generated by Dr. B. Striepen [University of Georgia; kindly provided by Dr. E. Robey (University of California, Berkeley)]. All tachyzoites were maintained in vitro via passage through human foreskin fibroblast cultures in DMEM with FCS (1%), penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (Fibroblast media). For experiments, tachyzoites were harvested and passed through a 3 μm track-etched membrane filter (Whatman) to remove fibroblast debris. Infections were performed at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1 unless otherwise indicated and were synchronized by brief centrifugation (200 × g for 4 min).

Degranulation

β-Hexosaminidase release

Cells were sensitized and plated in triplicate at a density of 5 × 105/well and incubated overnight. The next day, cells were washed with fibroblast media and parasites were introduced as described above. For some experiments, 1 μM cytochalasin D was added during infection to prevent invasion. Following infection, cells were washed three times with buffered saline solution (BSS: 135 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 5.6 mM glucose, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 1 mg/ml BSA) and β-hexosaminidase release in response to DNP-BSA was assessed as described previously (Naal et al., 2004).

Live cell degranulation imaging

Live cell degranulation imaging experiments were carried out as described previously (Cohen et al., 2012). Briefly, sensitized cells were plated overnight in 35 mm glass bottom dishes (MatTek) in the presence of FITC-dextran (1 mg/ml) and 5-HT serotonin (0.2 mM). The next day, cells were washed with fibroblast media and infected with RH-tomato tachyzoites as described above. Following 1 h of infection, cells were washed three times with BSS. Imaging was conducted at 37°C on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope at an image acquisition rate of 1.7 Hz. Cells were monitored for 1 min prior to addition of multivalent antigen, DNP-BSA (10 ng/ml), then monitored for an additional 9 min.

Western blotting

Sensitized, adherent cells were infected as described above. Following infection, cells were stimulated for 0–20 min, and whole cell western blotting samples were prepared and blotted as described previously (Young et al., 2005). Samples were run on Tris-glycine gels under reducing conditions. For assessment of phosphorylation, anti-phosphotyrosine (clone 4G10) (Millipore) was used, and pp72 was identified based on molecular weight. To assess sample loading, blots were reprobed with anti-actin (clone ACTN05; Neomarkers). Antibodies against PLCγ1 (Santa Cruz), PLCγ1-pY783, PLCγ2, and PLCγ2-pY1217 (Cell Signaling Technology) were used to assess PLCγ activity. To determine relative intensity, the normalized ratio of phosphorylated band intensity to loading control was calculated, and all values were then normalized as compared to the intensity of the control sample at 20 min post-stimulation.

Intracellular Ca2+ measurements

Fluorimetry

Measurement of intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in response to antigen (10 ng/ml DNP-BSA), 200 nM thapsigargin or 10 μM fMLP was carried out in tachyzoite infected cells using indo-1 as a Ca2+ indicator dye as described previously (Smith et al., 2010). Time-integrated responses were determined as the area under the stimulated time course minus the baseline over 400 s, normalized to the maximal response in Triton X-100 lysed cells (Field et al., 2000).

Live cell Ca2+ imaging

Single cell Ca2+ measurements in infected and control cells were conducted using Fluo-4 AM as described previously (Gadi et al., 2011) on the Leica SP5 confocal system with an image acquisition rate of 0.5 Hz.

Analysis of Ca2+ oscillations in individual cells was performed using Matlab software (Mathworks). Briefly, code was written to track the location and average fluorescence intensity of the green channel (Fluo-4) within a circular region of interest (ROI) in the cytoplasm of each cell. These measurements were plotted with respect to time, and the number of oscillations for each ROI, reflected by increases in fluorescence intensity, were enumerated.

Measurements of phosphoinositide (PIP2 and PIP3) localization

Cells were sparsely plated (1−3 × 105/ml) on # 1.5 coverslips or in 35 mm glass bottom dishes (MatTek). After overnight culture, cells were transfected with either PH- PLCδ-EGFP (Varnai and Balla, 1998) or PH-Akt-EGFP (Srinivasan et al., 2003) using 2 μg DNA and 8 μl Fugene HD (Roche Diagnostics) in 1 ml OptiMEM for 1 h before addition of 1 ng/ml phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate for 3–5 h to enhance DNA uptake (Gosse et al., 2005). Samples were then washed into full media and cultured for 16–24 h to allow for protein expression.

Transfected cells were infected for 1–2 h with RH-tomato parasites followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min at room temperature. Excess fixative was quenched by 10 mg/ml BSA in PBS with 0.01% sodium azide. Fixed cells were imaged on a Leica SP2 confocal system. Line scan analysis of equatorial cross sections using ImageJ (NIH) was performed using average fluorescence values to determine the ratio of the PH domain at the plasma membrane to that in the cytoplasm (Smith et al., 2010).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed with Prism software (Graphpad). All bar graphs display mean ± SEM unless otherwise noted. Statistical significance was determined by One-Way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) followed by Tukey's post test. Level of significance is denoted as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001.

Results

Ca2+ responses are reduced in T. gondii-infected neutrophils

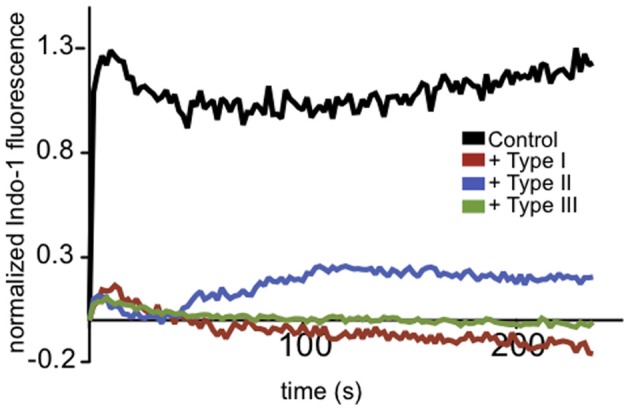

T. gondii is known to actively modulate signaling in the immune cells it infects (Laliberte and Carruthers, 2008). Ca2+ mobilization is central to many aspects of immune signaling, so we examined the effects of parasite infection on neutrophil Ca2+ responses to the bacterial chemotactic factor, fMLP. Freshly purified mouse neutrophils were isolated, purified and labeled with indo-1 to monitor Ca2+ mobilization stimulated by fMLP following infection by T. gondii. As shown in Figure 1, we found that the neutrophil response to fMLP was inhibited by infection with all types of T. gondii. These data provided initial evidence that Ca2+ signaling in an immune cell type that is an established host target for T. gondii is altered by parasite infection.

Figure 1.

T. gondii-infected neutrophils exhibit reduced Ca2+ responses to fMLP. Representative indo-1 fluorescence measurements of Ca2+ responses to 10 μM fMLP, added at t = 0, in control (black), Type I (red), Type II (blue), or Type III (green) infected cells (MOI 10:1).

Live microscopy is a powerful tool to probe the mechanistic aspects of Ca2+ responses, but our attempts to use this approach in neutrophils was hampered by their relatively short lifespan ex vivo and our findings that neutrophil adhesion on poly-L-lysine-coated glass, necessary for imaging, triggered spontaneous activation, including neutrophil extracellular trap formation (Abi Abdallah, unpublished observations; Abi Abdallah et al., 2012). To overcome these technical limitations, we utilized RBL mast cells as a model system more amenable for investigation of signaling mechanisms important for immune cell-mediated Ca2+ responses in the context of Toxoplasma infection. Mast cell signaling through the IgE receptor, FcεRI, is a well-studied immune signaling process that occurs on the time scale of minutes. An end result of this signaling is granule fusion and release of histamine, serine proteases and proteoglycans in a process termed degranulation (Blank and Rivera, 2004).

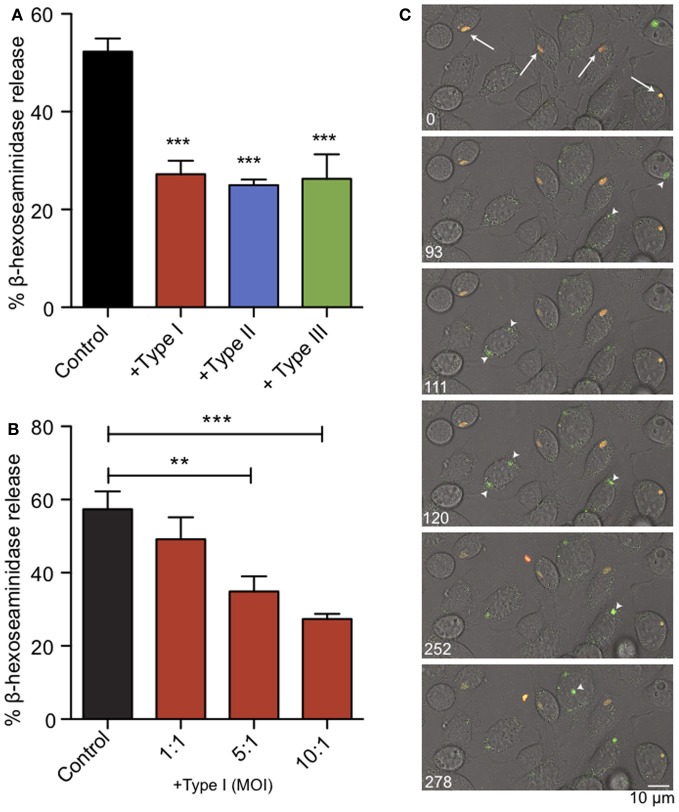

T. gondii infection rapidly inhibits antigen-mediated mast cell degranulation

We infected RBL-2H3 mast cells with Toxoplasma type I (RH), II (PTG), or III (CTG or VEG) tachyzoites. After 1 h we assessed the capacity of the infected cells to degranulate in response to multivalent antigen, DNP-BSA. In a bulk assay we found that acute T. gondii infection reduced degranulation by approximately 50%, irrespective of the genotype of parasite used (Figure 2A). Under these conditions, infection rates were between 50 and 70% and FcεRI receptor expression on the mast cell surface remained unchanged (N.L. Smith, data not shown). This inhibition directly correlated with multiplicity of infection (MOI), suggesting that inhibition is dependent on infection levels (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Acute T. gondii infection inhibits antigen-mediated mast cell degranulation. (A) RBL mast cells were infected with type I (RH, red), type II (PTG, blue) or type III (CTG or VEG, green) tachyzoites for 1 h at an MOI of 10:1 (resulting in 50–70% infection), and degranulation stimulated by antigen (1 ng/ml DNP-BSA) was assessed by β-hexosaminindase release. Results summarize an average of 5–7 experiments, and error bars represent SEM (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 compared to control uninfected cells). (B) A representative experiment showing inhibition of degranulation increases with increasing MOI. (C) Individual frames taken from live fluorescence confocal microscopy of degranulation events monitored by FITC-dextran bursts (green) in RBL cells infected with RH-tomato tachyzoites (red) and uninfected RBL cells in the same field. White arrows (timepoint 0) indicate infected cells. Arrowheads highlight degranulation events in uninfected cells (frames taken from supporting movie M1).

We used RH-tomato parasites in live imaging experiments to assess degranulation by FITC-dextran release (Figure 2C, movie M1). In these experiments, FITC-dextran is taken up into the granules of RBL mast cells. FITC fluorescence is pH sensitive and remains quenched in the acidic environment of the granules. Upon stimulation, granules fuse with the plasma membrane, their contents are exposed to a higher pH and local bursts of FITC-dextran fluorescence are detected (Cohen et al., 2012). We found that infected cells are defective in their response to antigen crosslinking and showed delayed exocytosis. Neighboring uninfected cells responded robustly to antigen as seen by bursts of FITC-dextran fluorescence from granules (Figure 2C, arrow heads) and apparent flattening and ruffling of the cells (movie M1). Taken together, these results indicate that T. gondii inhibits mast cell degranulation, and this inhibition directly correlates with infection.

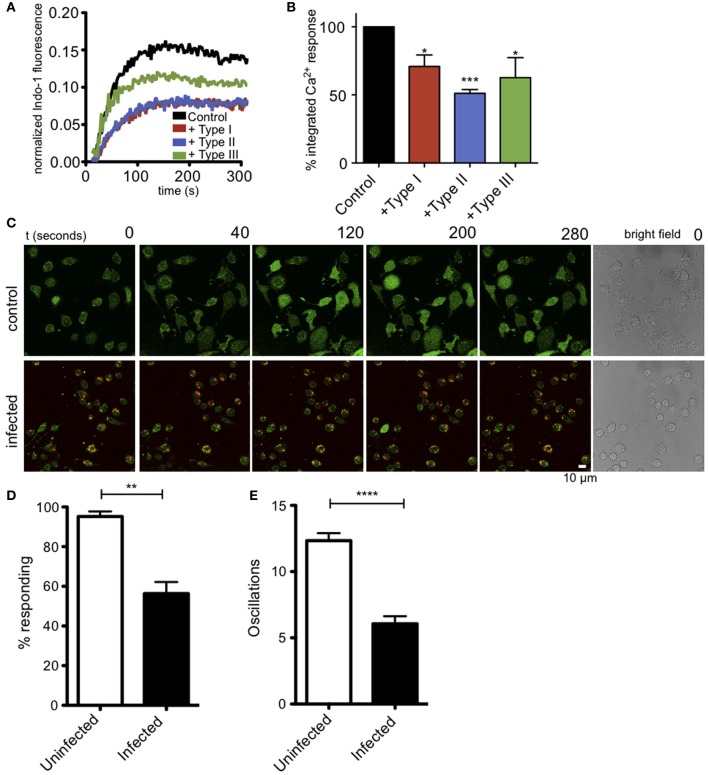

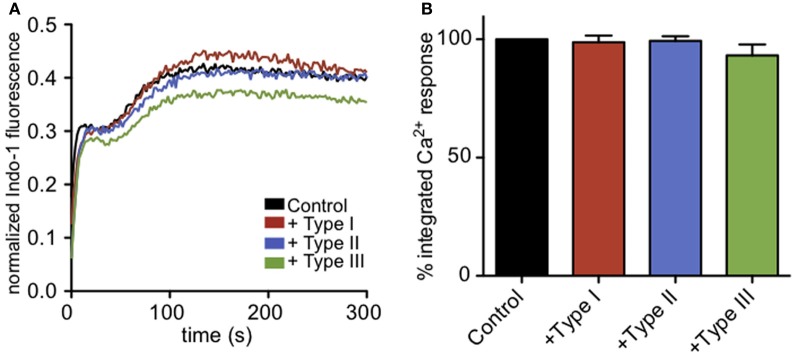

Ca2+ mobilization in response to antigen is reduced in Toxoplasma-infected RBL-2H3 mast cells

Ca2+ release from ER stores is mediated by binding of IP3 to its receptors in the ER membrane. This event triggers coupling of the ER-localized Ca2+ sensor, STIM1, and the plasma membrane Ca2+ channel Orai1, resulting in additional Ca2+ influx from extracellular space, a process known as store operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE). These events are important downstream steps in the pathway that leads to degranulation in mast cells (Di Capite and Parekh, 2009; Holowka et al., 2012). Measurement of intracellular Ca2+ in suspended RBL cells reveals that infection by T. gondii significantly reduces the Ca2+ response to antigen (Figure 3A). Integration of Ca2+ responses over 5 min shows a 39% reduction in Ca2+ mobilization in 3–5 independent experiments, averaged over all parasite types (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

T. gondii infection reduces antigen-mediated Ca2+ responses in RBL mast cells. (A) Representative indo-1 fluorescence measurements of Ca2+ responses to multivalent antigen (10 ng/ml DNP-BSA) in control uninfected (black), Type I-infected (red), Type II-infected (blue) or Type III-infected (green) infected cells (MOI 10:1). (B) Integrated Ca2+ responses over 300 s of stimulation as a percentage of control Ca2+ response. Histogram shows averages for 3–5 independent experiments. (C) Live Fluo-4 (green) Ca2+ imaging in uninfected or RH-tomato (red) infected RBL-cells. (see supporting movies M2 and M3). Quantification of the percentage of responding cells (D) or average number of Ca2+ oscillations per cell in 10 min (E) in live Ca2+ imaging experiments (n = 174 cells over 3 experiments). Error bars represent SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 relative to uninfected cells).

In these bulk population measurements, it is difficult to evaluate what percent of infected cells are inhibited. We directly addressed this question by conducting live cell imaging experiments to evaluate Ca2+ responses in individual cells. Figure 3C, top panel, and movie M2 show that control, uninfected cells exhibit robust Ca2+ signaling in response to antigen, with 94% of the cells responding with an average of 12 oscillations during a 10-min period. In contrast, as shown in Figure 3C, bottom, and movie M3, the RH-tomato infected cells are much less responsive, such that only 58% of cells containing one or more parasites respond, typically with a slower onset and with an average of 6 oscillations over the same time period. These parameters are compared in Figures 3D,E.

It is known that intracellular parasites interact extensively with the ER (Sinai and Joiner, 1997), and one possibility is that these interactions somehow block the exit of Ca2+ from the ER during antigen-stimulated, IP3-dependent depletion of ER Ca2+. Receptor-mediated, IP3-dependent release of Ca2+ from ER stores can be bypassed by treating cells with thapsigargin, a SERCA pump inhibitor, resulting in passive leakage of Ca2+ from the ER that activates SOCE. Under these conditions, cells infected with all types of T. gondii have Ca2+ responses comparable to uninfected cells (Figures 4A,B), showing that T. gondii is not directly blocking SOCE. These results contrast with those of Haroon and colleagues, who showed reduced thapsigargin-mediated Ca2+ responses in Toxoplasma-infected mouse neurons (Haroon et al., 2012). Collectively, our results indicate that a common factor, shared by the three genotypes of parasite, inhibits granule exocytosis via a mechanism that inhibits Ca2+ mobilization upstream of SOCE.

Figure 4.

Infection does not affect Ca2+ responses to ER store release by thapsigargin. (A) Representative indo-1 fluorescence measurements of Ca2+ responses to 200 nM thapsigargin in control (black), Type I (red), Type II (blue), or Type III (green) infected cells (MOI 10:1). (B) Integrated Ca2+ responses over 300 s of stimulation as a percentage of control Ca2+ response. Bars show average of 3–5 independent experiments. Error bars represent SEM.

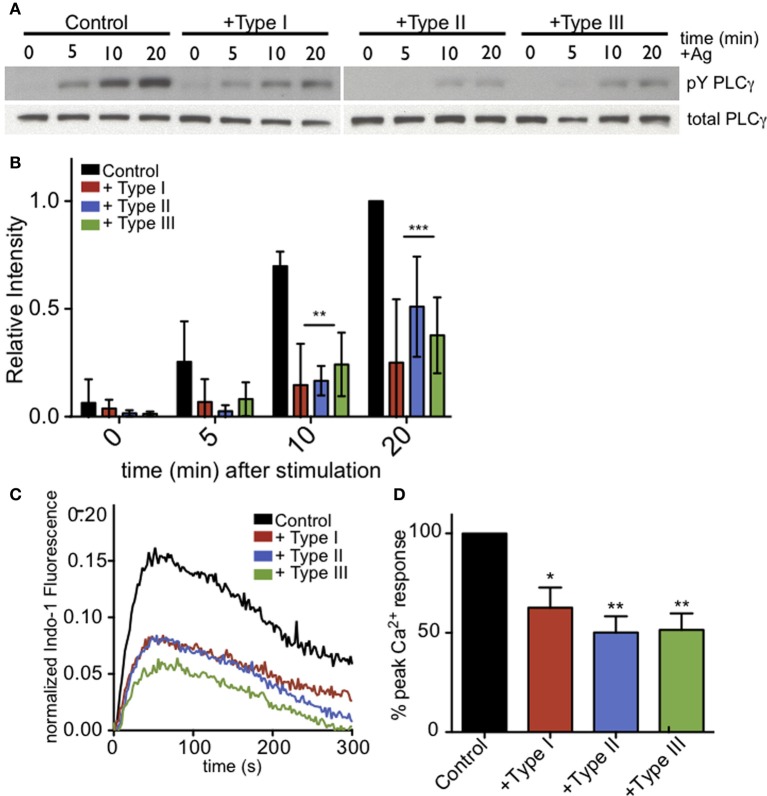

PLCγ activation is reduced in Toxoplasma-infected RBL-2H3 cells

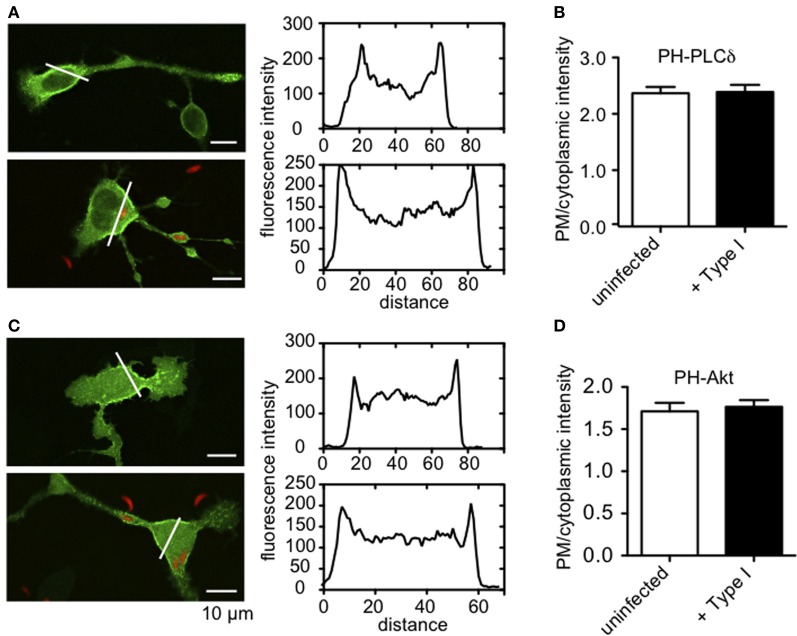

Antigen stimulation of FcεRI activates phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ), resulting in hydrolysis of PIP2 to DAG and IP3. This, in turn, triggers Ca2+ release from ER stores via IP3 receptors at the ER. One possible mechanism of inhibition of this process is that intracellular parasites might sequester PIP2, such that it is no longer available as a substrate for PLCγ. To address this possibility, we assessed whether infection by Toxoplasma alters the plasma membrane association of GFP-tagged PH-PLCδ that is highly specific for PIP2 (Ferguson et al., 1995). We found no appreciable differences in the abundance of PIP2 availability at the plasma membrane under these conditions (Figures A1A,B).

As phosphoinositide availability at the plasma membrane does not appear to be significantly changed in infected RBL cells, we next asked whether the parasite-mediated inhibition is due to a defect in PLCγ activation. For PLCγ to enzymatically cleave PIP2, it must be recruited to the plasma membrane and phosphorylated at specific tyrosine residues. Western blotting with anti-pY1217-PLCγ2 shows that antigen-stimulated phosphorylation at this residue is reduced in all infected samples (Figure 5A). At 10 min post-stimulation in the presence of types I, II and III parasites, Y1217-PLCγ2 phosphorylation is reduced by >65% in at least 3 independent experiments (Figure 5B). PLCγ1, like PLCγ2, shows reduced phosphorylation at its activating tyrosine, Y783 (N.L. Smith, data not shown).

Figure 5.

PLCγ2 activity is reduced in T. gondii-infected RBL-2H3 cells. (A) Representative western blot of phospho-PLCγ2 (top) or total PLCγ2 (bottom) in control or type I-,II- or III-infected (MOI 10:1, 1 h) cells lysed at 0, 5, 10, or 20 min after addition of multivalent antigen (10 ng/ml DNP-BSA). (B) Quantification of phospho-PLCγ2 analysis as shown in (A). Error bars represent SD of 4 independent experiments (**P < 0.01,***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 relative to uninfected cells). (C) Representative indo-1 fluorescence measurements of Ca2+ responses to 10 ng/ml DNP-BSA in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ in control uninfected (black), Type I-infected (red), Type II-infected (blue) or Type III-infected (green) cells (MOI 10:1). (D) Peak Ca2+ responses in infected cells as a percentage of control Ca2+ response of uninfected cells in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. Histogram shows averages of 3 independent experiments. Error bars represent SEM (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 relative to control cells).

To further assess the activity of PLCγ, we asked if antigen-mediated IP3 generation was reduced in T. gondii infected RBL cells. Specifically, we examined Ca2+ mobilization in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ as a measure of PLCγ-dependent Ca2+ release from ER stores. Figure 5C is a representative experiment that shows all parasite types significantly reduce the amount of Ca2+ released from ER stores in response to antigen. Over multiple experiments, parasite infection reduced the Ca2+ release from ER stores by 37, 50, and 49% for Types I, II, and III, respectively (Figure 5D).

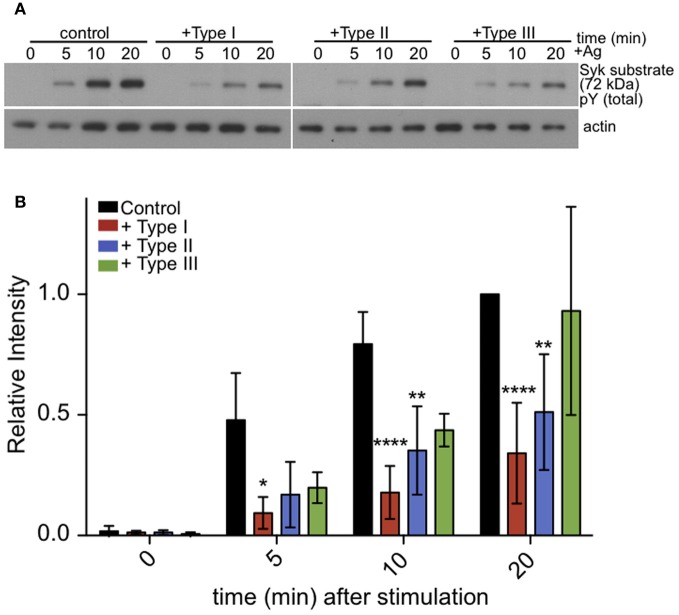

Syk kinase activity is reduced by T. gondii infection

Following crosslinking of IgE/FcεRI complexes by multivalent antigen, tyrosine residues within ITAMs are phosphorylated in the cytoplasmic segments of the β and γ subunits of FcεRI. This, in turn, recruits and activates Syk tyrosine kinase. Syk kinase has a number of downstream targets, including PLCγ. Therefore, we asked if antigen stimulation of the phosphorylation of additional Syk substrates, detected as pp72 (Benhamou et al., 1993), is altered in infected cells. As we saw for PLCγ, stimulated phosphorylation of Syk substrate pp72 is also reduced in infected cells (Figures 6A,B). These results suggest that inhibition of PLCγ-mediated hydrolysis of PIP2 is due to reduction in the activation of Syk kinase.

Figure 6.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of pp72 Syk substrate is reduced in T. gondii infected cells. IgE-sensitized RBL cells were infected for 1 h with Type I, II or III tachyzoites as indicated. Antigen-stimulated cells were lysed at 0, 5, or 10 min after addition of multivalent antigen (10 ng/ml DNP-BSA). (A) Representative blot: Top panel shows phosphorylation of pp72 Syk substrate. Bottom panel shows loading control (α-tubulin) (B) Quantification of Syk substrate band intensity. Error bars represent SD of 4 independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 0.0001 relative to uninfected cells).

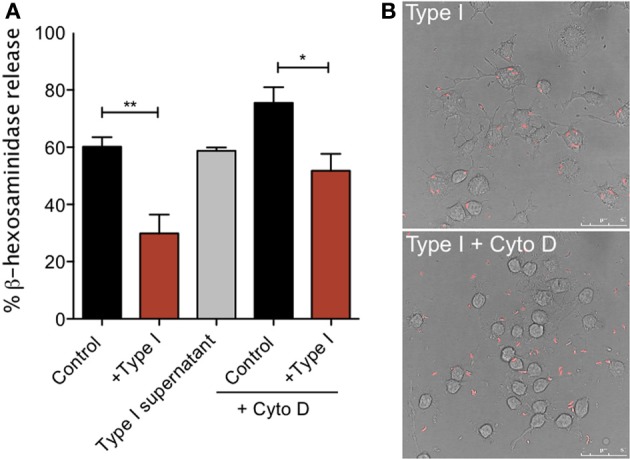

Inhibition of mast cell signaling by T. gondii requires parasite attachment, but not entry

Our single cell Ca2+ and degranulation measurements indicate that the inhibitory action of T. gondii requires direct contact between the host cell and parasite and possibly parasite entry. To more directly address these issues, we compared degranulation responses in RBL cells infected with the Type I parasites to responses to cells that were incubated with the supernatant from an equivalent number of parasites (Type I supernatant). As shown in Figure 7A, RH supernatant did not inhibit antigen-stimulated degranulation under conditions in which infection by intact parasites was effective (+ Type I vs. Type I supernatant). Additionally, degranulation is not inhibited by heat-killed parasites, fixed parasites or by supernatants from infected fibroblasts (N.L. Smith, data not shown).

Figure 7.

Tachyzoite attachment, but not invasion, is necessary for inhibition of degranulation. (A) RBL-2H3 cells were incubated with parasites (Type I) in the presence or absence of cytochalasin D or with supernatants from parasites (Type I supernatant). Degranulation stimulated by multivalent antigen (10 ng/ml DNP-BSA) was assessed by β-hexosaminindase release after 1 h of infection as described in Materials and Methods. For Control, + Type I, Control + Cyto D and + Type I + Cyto D error bars represent SEM (n = 4) (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 relative to control cells); for Type I supernatant, error bar represents range (n = 2). (B) Representative confocal microscopy of RBL cells infected with RH tomato parasites in the presence (bottom panel) or absence (top panel) of cytochalasin D.

Parasite entry depends primarily on the parasite actin cytoskeleton (Dobrowolski and Sibley, 1996; Hakansson et al., 2001). Therefore, infections carried out in the presence of the inhibitor of actin polymerization, cytochalasin D, result in a frustrated state where parasites attach and secrete proteins into the host cell but do not complete invasion (Hakansson et al., 2001). Cytochalasin D is known to enhance degranulation responses of RBL cells to antigen (Frigeri and Apgar, 1999), and, as expected, we see robust stimulated degranulation under these conditions (Figure 7A, Control + Cyto D). However, degranulation in the presence of cytochalasin D and parasites is still significantly reduced compared to cytochalasin D treatment alone (Figure 7A). The average inhibition over three independent experiments is 32%. Microscopic observations under these conditions confirmed that infection rates in the presence of cytochalasin D were extremely low: 4% in cytochalasin D treated samples compared to approximately 70% under control conditions (Figure 7B). These results indicate that inhibition under these conditions is due to attached, but not intracellular parasites. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that the attached parasite directly inhibits the host's tyrosine kinase activity without entering the cell, it is more likely that the agent responsible for mediating inhibition of mast cell signaling is secreted into the cell at the initiation of the invasion process.

Discussion

Based on its global prevalence and its capacity to infect a multitude of hosts, T. gondii is regarded as one of the world's most successful parasites. It now appears that the success of this parasite is due, in part, to the arsenal of immune-modulatory mechanisms it employs. For example, this parasite blocks macrophage and dendritic cell responses to IFN-γ and LPS signaling. In part, this appears to be due to exploitation of STAT signaling as well as interference with chromatin remodeling (Leng and Denkers, 2009; Leng et al., 2009b). Our current study uncovers another mechanistic target of parasite interference, namely PLCγ-mediated Ca2+ mobilization.

In vivo, T. gondii is known to preferentially infect immune effector cells, including neutrophils, macrophages and dendritic cells (Denkers and Butcher, 2005; Bierly et al., 2008). Accordingly, we found that this infection suppresses receptor-mediated Ca2+ mobilization in murine neutrophils (Figure 1). To further characterize the mechanism of such effects, we chose the well-studied immune signaling model, FcεRI in mast cells, to address the molecular basis of T. gondii effects on acute immune signaling events that rely on Ca2+ signaling. FcεRI-triggered degranulation in mast cells begins within minutes of stimulation and continues over several tens of minutes. Intracellular Ca2+ levels are tightly regulated, and elevation of intracellular Ca2+ is critical in immune responses in multiple cell types and contexts (Andersson et al., 1986; Penner and Neher, 1988; Putney, 2009). Host Ca2+ responses in macrophages have been implicated in regulating the initial recognition of T. gondii that results in MAPK activity leading to IL-12 production (Masek et al., 2006). Furthermore, intracellular parasites are sensitive to host Ca2+ responses, and exogenous stimulation Ca2+ influx by treatment with Ca2+ ionophore triggers tachyzoite egress (Caldas et al., 2007).

Ca2+ mobilization is a central and well-studied aspect of IgE/FcεRI-mediated signaling in mast cells, including its role in granule exocytosis and cytokine production (Holowka et al., 2012). Our initial experiments revealed that parasite infection suppresses degranulation responses in RBL cells (Figure 2), and thus its inhibition of Ca2+ mobilization was a likely suspect. We showed that parasite infection blocks antigen-triggered, but not thapsigargin-triggered Ca2+ elevation (Figures 3, 4), indicating that infection acts upstream of Ca2+ release from stores. Inhibition of Ca2+ mobilization by T. gondii in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ further supports this explanation (Figure 5). Hydrolysis of PIP2 mediated by PLCγ to produce IP3 and DAG is critically important in Ca2+ mobilization by antigen in mast cells. One possible mechanism to account for decreased Ca2+ store release in response to antigen is that the parasite alters the amount or availability of PLCγ's substrate, PIP2, at the plasma membrane. However, our results are inconsistent with this explanation, as we detect no significant change in PIP2 levels at the plasma membrane due to infection by T. gondii. We do, however, observe a reduction in the level of activating tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ during infection (Figure 5), suggesting that Toxoplasma is reducing the host's capacity to hydrolyze PIP2.

PLCγ1 activity in mast cells is regulated by PI3-kinase-mediated production of PIP3 (Barker et al., 1998), but our results indicate that the parasite does not significantly change the level of PIP3 in infected cells (Figures A1C,D). Rather, our findings that phosphorylation of Syk substrates pp72, as well as PLCγ, are reduced in infected RBL cells, point to inhibition of the tyrosine kinase signaling cascade that culminates in PIP2 hydrolysis as the most immediate consequence of T. gondii infection. The earliest target in this cascade is not yet clear, as T. gondii infection caused some reduction in FcεRI ITAM phosphorylation by Lyn kinase that was not statistically significant (N.L. Smith, unpublished observations). Our data collectively suggest a model in which one or more T. gondii-derived proteins act directly to reduce the activity of PLCγ by inhibiting Syk activation, thereby reducing the levels of IP3 and inhibiting subsequent signaling steps (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Ca2+-mediated signaling through FcεRI is blocked by a T. gondii-secreted product. Crosslinking of IgE/FcεRI complexes by multivalent antigen leads to phosphorylation of FcεRI subunits by Lyn kinase and subsequent recruitment and activation of Syk, which can then phosphorylate the adaptor protein LAT and other substrates. Consequent activation of PLCγ produces DAG and IP3, and IP3 activates IP3 receptors at the endoplasmic reticulum, causing Ca2+ release from ER stores and additional influx through Orai1 channels at the plasma membrane surface. Ca2+ mobilization and activation of PKC via DAG production is necessary for maximal degranulation of secretory lysosomes. The data presented here suggest that a secreted product of T. gondii blocks this signaling at the level of Syk phosphorylation leading to PLCγ activation.

Furthermore, our results suggest that a secreted product from T. gondii mediates this inhibition at an early step during the invasion process. Previous work determined that invasion is a multi-step process (Carruthers and Boothroyd, 2007), and, in early steps, parasites attach to the host plasma membrane and release the contents of the rhoptries into the cell (Hakansson et al., 2001). Quantitative trait locus analysis revealed that rhoptry proteins, including ROP16 and ROP18, which are secreted during invasion, are key virulence factors in T. gondii infection (Saeij et al., 2006; Taylor et al., 2006). Recently, ROP16 has been shown to directly phosphorylate STAT molecules (Yamamoto et al., 2009; Ong et al., 2010). However, lack of parasite strain specificity argues against a role for ROP16 and ROP18 in the effects reported here, as there are documented differences in the activity of these ROP proteins in the three types of parasites evaluated (Saeij et al., 2006; Taylor et al., 2006; Boyle et al., 2008). Furthermore, we tested ROP16 null parasites and found them equally capable of blocking Ca2+ responses (N.L. Smith, unpublished observations). Nevertheless, ROP protein early release, relation to virulence, and immunomodulatory capabilities make these proteins attractive candidates for the Toxoplasma secreted factor responsible for the reduction in Ca2+ mobilization (Ong et al., 2010; Butcher et al., 2011). Future work will focus on identifying which parasite-derived protein(s) are responsible for the inhibition we observe.

We also note that while our results indicate that Toxoplasma inhibits mast cell immune responses, this is not contradictory to reports that mast cell responses contribute to the primary host response to Toxoplasma in vivo (Ferreira et al., 2004; Sawesi et al., 2010). Our data show that PLCγ-mediated responses are reduced by Toxoplasma infection in vitro. Furthermore, our findings that PLCβ-mediated neutrophil responses are inhibited by Toxoplasma infection (Figure 1), as are voltage-gated neuronal Ca2+ responses (Haroon et al., 2012), indicate that there are likely multiple mechanisms employed by T. gondii to subvert normal Ca2+ signaling. In future studies it will be important to assess whether inhibition of Ca2+ signaling is manifest in other immune cells infected by T. gondii, as well as the mechanisms utilized. Collectively, our results indicate that T. gondii targets Syk-dependent PLCγ activation as one mechanism to interfere with immune signaling that depends on Ca2+ mobilization.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carol Bayles for maintaining the Cornell Microscopy and Imaging Facility and Rodman Getchell for maintaining the SP5 Leica Confocal system. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [Grant R01AI022449] and R01AI50617 (Eric Y. Denkers).

Appendix

Figure A1.

PIP2 and PIP3 levels at the plasma membrane are not altered by T. gondii infection. (A) Representative images showing uninfected (top) or RH-tomato infected (bottom) RBL cells transiently transfected with PH-PLCδ-EGFP. Accompanying fluorescence intensity profiles are taken along the white lines indicated in each image. (B) Ratio of plasma membrane to cytoplasmic PH-PLCδ-EGFP fluorescence [given by intensity profiles as shown in (A)] as a relative measure of PIP2 at the plasma membrane. (C) Representative images showing uninfected (top) or RH-tomato infected (bottom) RBL cells transiently transfected with PH-Akt-EGFP. Accompanying fluorescence intensity profiles are taken along the white lines indicated in each image. (D) Ratio of plasma membrane to cytoplasmic PH-Akt-EGFP fluorescence as a relative measure of PIP3 at the plasma membrane. Data in (B) and (D) represent at least 30 cells for each condition collected over 3 experiments. Error bars indicate SEM.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/Microbial_Immunology/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00179/abstract

Live Imaging of RBL cell degranulation shows reduced responses in RH-tomato (red) infected cells compared to neighboring uninfected cells. Images were acquired at a rate of 1.7 Hz. Multivalent antigen (10 ng/ml DNP-BSA) was added when indicated in movie and degranulation events are observed as FITC-dextran bursts (green). Movie plays at 10 × speed.

Live Ca2+ imaging in uninfected RBL cells shows robust response to antigen. RBL cells were loaded with fluo-4 (green) and imaged at a rate of 0.5 Hz. Multivalent antigen (10 ng/ml DNP-BSA) was added when indicated in movie. Movie plays at 12 × speed.

Live Ca2+ imaging in RH-tomato (red) infected RBL cells show reduced response to antigen. RBL cells were loaded with fluo-4 (green) and imaged at a rate of 0.5 Hz. Multivalent antigen (10 ng/ml DNP-BSA) was added when indicated in movie. Movie plays at 12 × speed.

References

- Abi Abdallah D. S., Egan C. E., Butcher B. A., Denkers E. Y. (2011). Mouse neutrophils are professional antigen-presenting cells programmed to instruct Th1 and Th17 T-cell differentiation. Int. Immunol. 23, 317–326 10.1093/intimm/dxr007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abi Abdallah D. S., Lin C., Ball C. J., King M. R., Duhamel G. E., Denkers E. Y. (2012). Toxoplasma gondii triggers release of human and mouse neutrophil extracellular traps. Infect. Immun. 80, 768–777 10.1128/IAI.05730-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson T., Dahlgren C., Pozzan T., Stendahl O., Lew P. D. (1986). Characterization of fMet-Leu-Phe receptor-mediated Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane of human neutrophils. Mol. Pharmacol. 30, 437–443 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker S. A., Caldwell K. K., Pfeiffer J. R., Wilson B. S. (1998). Wortmannin-sensitive phosphorylation, translocation, and activation of PLCgamma1, but not PLCgamma2, in antigen-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 483–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhamou M., Ryba N. J., Kihara H., Nishikata H., Siraganian R. P. (1993). Protein-tyrosine kinase p72syk in high affinity IgE receptor signaling. Identification as a component of pp72 and association with the receptor gamma chain after receptor aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 23318–23324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierly A. L., Shufesky W. J., Sukhumavasi W., Morelli A. E., Denkers E. Y. (2008). Dendritic cells expressing plasmacytoid marker PDCA-1 are Trojan horses during Toxoplasma gondii infection. J. Immunol. 181, 8485–8491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank U., Rivera J. (2004). The ins and outs of IgE-dependent mast-cell exocytosis. Trends Immunol. 25, 266–273 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle J. P., Saeij J. P., Harada S. Y., Ajioka J. W., Boothroyd J. C. (2008). Expression quantitative trait locus mapping of toxoplasma genes reveals multiple mechanisms for strain-specific differences in gene expression. Eukaryot. Cell 7, 1403–1414 10.1128/EC.00073-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun A., Gessner J. E., Varga-Szabo D., Syed S. N., Konrad S., Stegner D., et al. (2009). STIM1 is essential for Fcgamma receptor activation and autoimmune inflammation. Blood 113, 1097–1104 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher B. A., Fox B. A., Rommereim L. M., Kim S. G., Maurer K. J., Yarovinsky F., et al. (2011). Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry kinase ROP16 activates STAT3 and STAT6 resulting in cytokine inhibition and arginase-1-dependent growth control. PLoS Pathog. 7: e1002236 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher B. A., Kim L., Panopoulos A. D., Watowich S. S., Murray P. J., Denkers E. Y. (2005). IL-10-independent STAT3 activation by Toxoplasma gondii mediates suppression of IL-12 and TNF-alpha in host macrophages. J. Immunol. 174, 3148–3152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldas L. A., de Souza W., Attias M. (2007). Calcium ionophore-induced egress of Toxoplasma gondii shortly after host cell invasion. Vet. Parasitol. 147, 210–220 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambier J. C. (1995). Antigen and Fc receptor signaling. The awesome power of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM). J. Immunol. 155, 3281–3285 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers V., Boothroyd J. C. (2007). Pulling together: an integrated model of Toxoplasma cell invasion. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 83–89 10.1016/j.mib.2006.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R., Corwith K., Holowka D., Baird B. (2012). Spatiotemporal resolution of mast cell granule exocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 125, 2986–2994 10.1242/jcs.102632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denkers E. Y., Butcher B. A. (2005). Sabotage and exploitation in macrophages parasitized by intracellular protozoans. Trends Parasitol. 21, 35–41 10.1016/j.pt.2004.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Capite J., Parekh A. B. (2009). CRAC channels and Ca2+ signaling in mast cells. Immunol. Rev. 231, 45–58 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00808.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrowolski J. M., Sibley L. D. (1996). Toxoplasma invasion of mammalian cells is powered by the actin cytoskeleton of the parasite. Cell 84, 933–939 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81071-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey J. P. (1998). Advances in the life cycle of Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 28, 1019–1024 10.1016/S0020-7519(98)00023-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson K. M., Lemmon M. A., Sigler P. B., Schlessinger J. (1995). Scratching the surface with the PH domain. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2, 715–718 10.1038/nsb0995-715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti M. E., Nalli M., Biondi C., Colamussi M. L., Pavan B., Traniello S., et al. (2001). Modulation of neutrophil phospholipase C activity and cyclic AMP levels by fMLP-OMe analogues. Cell Signal 13, 233–240 10.1016/S0898-6568(01)00140-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira G. L. S., Mineo J. R., Oliveira J. G., Ferro V. E. A. Souza M. A. Santos A. A. D. (2004). Toxoplasma gondii and mast cell interactions in vivo and in vitro: experimental infection approaches in Calomys callosus (Rodentia, Cricetidae). Microbes. Infect. 6, 172–181 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field K. A., Apgar J. R., Hong-Geller E., Siraganian R. P., Baird B., Holowka D. (2000). Mutant RBL mast cells defective in Fc epsilon RI signaling and lipid raft biosynthesis are reconstituted by activated Rho-family GTPases. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 3661–3673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigeri L., Apgar J. R. (1999). The role of actin microfilaments in the down-regulation of the degranulation response in RBL-2H3 mast cells. J. Immunol. 162, 2243–2250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadi D., Wagenknecht-Wiesner A., Holowka D., Baird B. (2011). Sequestration of phosphoinositides by mutated MARCKS effector domain inhibits stimulated Ca(2+) mobilization and degranulation in mast cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 4908–4917 10.1091/mbc.E11-07-0614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidwani A., Brown H. A., Holowka D., Baird B. (2003). Disruption of lipid order by short-chain ceramides correlates with inhibition of phospholipase D and downstream signaling by FcepsilonRI. J. Cell Sci. 116, 3177–3187 10.1242/jcs.00621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosse J. A., Wagenknecht-Wiesner A., Holowka D., Baird B. (2005). Transmembrane sequences are determinants of immunoreceptor signaling. J. Immunol. 175, 2123–2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakansson S., Charron A. J., Sibley L. D. (2001). Toxoplasma evacuoles: a two-step process of secretion and fusion forms the parasitophorous vacuole. EMBO J. 20, 3132–3144 10.1093/emboj/20.12.3132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon F., Handel U., Angenstein F., Goldschmidt J., Kreutzmann P., Lison H., et al. (2012). Toxoplasma gondii actively inhibits neuronal function in chronically infected mice. PLoS ONE 7:e35516 10.1371/journal.pone.0035516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holowka D., Calloway N., Cohen R., Gadi D., Lee J., Smith N. L., et al. (2012). Roles for Ca2+ mobilization in mast cell functions. Front. Immunol. 3:104 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holowka D., Gosse J. A., Hammond A. T., Han X., Sengupta P., Smith N. L., et al. (2005). Lipid segregation and IgE receptor signaling: a decade of progress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1746, 252–259 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Hoffmann F. W., Fay J. D., Hashimoto A. C., Chapagain M. L., Kaufusi P. H., et al. (2012). Stimulation of unprimed macrophages with immune complexes triggers a low output of nitric oxide by calcium-dependent neuronal nitric-oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 4492–4502 10.1074/jbc.M111.315598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongstra-Bilen J., Puig Cano A., Hasija M., Xiao H., Smith C. I., Cybulsky M. I. (2008). Dual functions of Bruton's tyrosine kinase and Tec kinase during Fcgamma receptor-induced signaling and phagocytosis. J. Immunol. 181, 288–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laliberte J., Carruthers V. B. (2008). Host cell manipulation by the human pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 65, 1900–1915 10.1007/s00018-008-7556-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert H., Barragan A. (2010). Modelling parasite dissemination: host cell subversion and immune evasion by Toxoplasma gondii. Cell Microbiol. 12, 292–300 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01417.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng J., Butcher B. A., Denkers E. Y. (2009a). Dysregulation of macrophage signal transduction by Toxoplasma gondii: past progress and recent advances. Parasite Immunol. 31, 717–728 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2009.01122.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng J., Butcher B. A., Egan C. E., Abdallah D. S., Denkers E. Y. (2009b). Toxoplasma gondii prevents chromatin remodeling initiated by TLR-triggered macrophage activation. J. Immunol. 182, 489–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng J., Denkers E. Y. (2009). Toxoplasma gondii inhibits covalent modification of histone H3 at the IL-10 promoter in infected macrophages. PLoS ONE 4:e7589 10.1371/journal.pone.0007589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H. T., Beaven M. A. (2009). Regulation of Ca2+ signaling with particular focus on mast cells. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 29, 155–186 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v29.i2.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masek K. S., Fiore J., Leitges M., Yan S. F., Freedman B. D., Hunter C. A. (2006). Host cell Ca2+ and protein kinase C regulate innate recognition of Toxoplasma gondii. J. Cell Sci. 119, 4565–4573 10.1242/jcs.03206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe D. D., Baram D., Mekori Y. A. (1997). Mast cells. Physiol. Rev. 77, 1033–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naal R. M., Tabb J., Holowka D., Baird B. (2004). In situ measurement of degranulation as a biosensor based on RBL-2H3 mast cells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 20, 791–796 10.1016/j.bios.2004.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong Y. C., Reese M. L., Boothroyd J. C. (2010). Toxoplasma rhoptry protein 16 (ROP16) subverts host function by direct tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT6. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 28731–28740 10.1074/jbc.M110.112359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner R., Neher E. (1988). Secretory responses of rat peritoneal mast cells to high intracellular calcium. FEBS Lett. 226, 307–313 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81445-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner R. G., Lee B., Conrad D. H., Holowka D., Baird B., Goldstein B. (1992). Aggregation of IgE-receptor complexes on rat basophilic leukemia cells does not change the intrinsic affinity but can alter the kinetics of the ligand-IgE interaction. Biochemistry 31, 5350–5356 10.1021/bi00138a015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney J. W. (2009). Capacitative calcium entry: from concept to molecules. Immunol. Rev. 231, 10–22 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00810.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera J., Gilfillan A. M. (2006). Molecular regulation of mast cell activation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 117, 1214–1225, quiz 1226. 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeij J. P., Boyle J. P., Coller S., Taylor S., Sibley L. D., Brooke-Powell E. T., et al. (2006). Polymorphic secreted kinases are key virulence factors in toxoplasmosis. Science 314, 1780–1783 10.1126/science.1133690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawesi O., Spillmann D., Lunden A., Wernersson S., Abrink M. (2010). Serglycin-independent release of active mast cell proteases in response to Toxoplasma gondii infection. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 38005–38013 10.1074/jbc.M110.118471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley L. D. (2004). Intracellular parasite invasion strategies. Science 304, 248–253 10.1126/science.1094717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinai A. P., Joiner K. A. (1997). Safe haven: the cell biology of nonfusogenic pathogen vacuoles. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51, 415–462 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N. L., Hammond S., Gadi D., Wagenknecht-Wiesner A., Baird B., Holowka D. (2010). Sphingosine derivatives inhibit cell signaling by electrostatically neutralizing polyphosphoinositides at the plasma membrane. Self Nonself 1, 133–143 10.4161/self.1.2.11672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S., Wang F., Glavas S., Ott A., Hofmann F., Aktories K., et al. (2003). Rac and Cdc42 play distinct roles in regulating PI(3,4,5)P3 and polarity during neutrophil chemotaxis. J. Cell Biol. 160, 375–385 10.1083/jcb.200208179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S., Barragan A., Su C., Fux B., Fentress S. J., Tang K., et al. (2006). A secreted serine-threonine kinase determines virulence in the eukaryotic pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Science 314, 1776–1780 10.1126/science.1133643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnai P., Balla T. (1998). Visualization of phosphoinositides that bind pleckstrin homology domains: calcium- and agonist-induced dynamic changes and relationship to myo-[3H]inositol-labeled phosphoinositide pools. J. Cell Biol. 143, 501–510 10.1083/jcb.143.2.501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weetall M., Holowka D., Baird B. (1993). Heterologous desensitization of the high affinity receptor for IgE (Fc epsilon R1) on RBL cells. J. Immunol. 150, 4072–4083 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Huo J., Lee K. G., Kurosaki T., Lam K. P. (2009). Phospholipase Cgamma2 is critical for Dectin-1-mediated Ca2+ flux and cytokine production in dendritic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 7038–7046 10.1074/jbc.M806650200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M., Ma J. S., Mueller C., Kamiyama N., Saiga H., Kubo E., et al. (2011). ATF6beta is a host cellular target of the Toxoplasma gondii virulence factor ROP18. J. Exp. Med. 208, 1533–1546 10.1084/jem.20101660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M., Standley D. M., Takashima S., Saiga H., Okuyama M., Kayama H., et al. (2009). A single polymorphic amino acid on Toxoplasma gondii kinase ROP16 determines the direct and strain-specific activation of Stat3. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2747–2760 10.1084/jem.20091703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R. M., Zheng X., Holowka D., Baird B. (2005). Reconstitution of regulated phosphorylation of FcepsilonRI by a lipid raft-excluded protein-tyrosine phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 1230–1235 10.1074/jbc.M408339200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Live Imaging of RBL cell degranulation shows reduced responses in RH-tomato (red) infected cells compared to neighboring uninfected cells. Images were acquired at a rate of 1.7 Hz. Multivalent antigen (10 ng/ml DNP-BSA) was added when indicated in movie and degranulation events are observed as FITC-dextran bursts (green). Movie plays at 10 × speed.

Live Ca2+ imaging in uninfected RBL cells shows robust response to antigen. RBL cells were loaded with fluo-4 (green) and imaged at a rate of 0.5 Hz. Multivalent antigen (10 ng/ml DNP-BSA) was added when indicated in movie. Movie plays at 12 × speed.

Live Ca2+ imaging in RH-tomato (red) infected RBL cells show reduced response to antigen. RBL cells were loaded with fluo-4 (green) and imaged at a rate of 0.5 Hz. Multivalent antigen (10 ng/ml DNP-BSA) was added when indicated in movie. Movie plays at 12 × speed.