Abstract

Introduction

Endometriosis is defined as overgrowth of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity. Endometriosis may be asymptomatic or associated with dysmenorrheal symptoms, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, abnormal uterine bleeding and infertility. The aim of this study was to explore the risk factors related to endometriosis among infertile Iranian women.

Material and methods

In this case control study, infertile women referred for laparoscopy and infertility workup to two referral infertility clinics in Tehran, Iran were studied. According to the laparoscopy findings, women were divided into case (women who had pelvic endometriosis) and control (women with normal pelvis) groups. The case group was divided into two subgroups: stage I and II of endometriosis were considered as mild while stage III and IV were categorized as severe endometriosis. A questionnaire was completed for each patient.

Results

Logistic regression showed that age, duration of infertility, body mass index (BMI), duration of menstrual cycle, abortion history, dyspareunia, pelvic pain and family history of endometriosis are independent predictive factors for any type of endometriosis. In addition, it was shown that education, duration of infertility, BMI, amount and duration of menstrual bleeding, menstrual pattern, dyspareunia, pelvic pain and family history of endometriosis are independent predictive factors of severe endometriosis. The AUCs for these models were 0.781 (0.735-0.827) and 0.855 (0.810-0.901) for any type of endometriosis and severe endometriosis, respectively.

Conclusions

It seems that any type of endometriosis and severe ones could be predicted according to demographic, menstrual and reproductive characteristics of infertile women.

Keywords: endometriosis, infertility, risk factors, laparoscopy, severe endometriosis

Introduction

Endometriosis is a common gynecological disorder in which endometrial tissue (glandular epithelium and stroma) is found outside the uterine cavity [1]. It has been estimated to affect 2.5-3.3% of women of childbearing age [2]. Clinical presentations of endometriosis varied from asymptomatic to signs and symptoms including dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, abnormal menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia and/or metrorrhagia), subfertility and infertility [3, 4].

Although the pathogenesis of endometriosis is still unknown, the most common etiology is believed to involve retrograde menstruation. Almost all women have some menstrual effluent that passes through the fallopian tubes during menstruation, but only a minority develops endometriosis due to the fact that those cells can be cleared by peritoneal macrophages [5].

One of the most important complications of endometriosis is reduced fertility and infertility. Although endometriosis affects approximately 5% of the general population, its prevalence may be as high as 30% in infertile women [6].

One of the challenging subjects in endometriosis is lack of non-invasive tests by which accurate diagnosis can be made [5]. Endometriosis is always finally diagnosed by visualizing the lesions, cysts, implants, and nodules by laparoscopy. Nevertheless, there are accompanying symptoms that may be indicative such as pelvic pain, adnexal masses, and dyspareunia [7] or some biochemical markers which are useful in detecting and monitoring endometriosis such as cancer antigen-125 (CA-125) [8].

In order to facilitate diagnosis of endometriosis by non-invasive methods, it is very important to know the risk factors which make women susceptible to endometriosis. By knowing the risk factors, women who may be at a high risk of developing endometriosis may be rapidly diagnosed so that serious complications of endometriosis such as infertility can be prevented by diagnosis and treatment of women suffering from endometriosis in earlier stages (I and II).

Several studies have surveyed these risk factors. Missmer et al. showed that age, race, body mass index (BMI), alcohol usage, and cigarette smoking were associated with the incidence of endometriosis in the USA. They also indicated that some of these associations may differ by infertility status at the time of laparoscopic diagnosis [9]. Calhaz-Jorge et al. found that prevalence of endometriosis in subfertile women was related to race, BMI, irregular menstrual cycles, intensity of menstrual flow, dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, obstetrics history, oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) use, and smoking habits [10]. According to these controversies about risk factors associated with endometriosis and the effect of race and infertility in this regard, we planned this study to survey the relation between endometriosis and these suggested risk factors and establish a practical model in infertile Iranian women referred to Royan Institute and the infertility clinic of Arash Women's Hospital, two of the major referral centers of infertility in Tehran, Iran. As it was shown, the spatial incidence of endometriosis in some regions may be different due to environmental risk and presence of chemical pollutants [11]; therefore we selected studied women from these referral infertility centers in Tehran, the capital of Iran.

Material and methods

This case control study was performed on infertile women referred for laparoscopy and infertility workup. This study was carried out at Royan Institute and Arash Women's Hospital, two referral infertility clinics in Tehran, Iran, between April 2009 and March 2010. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Royan Institute. All patients signed an informed consent form. The total number of infertile women who underwent diagnostic laparoscopy during the period of the study was 520. Women who had abnormalities other than endometriosis at laparoscopy were excluded from the study (117 women). Four hundred and three women were included in the study and were divided, according to laparoscopy findings, into two groups: a case group, consisting of women with pelvic endometriosis, and a control group including women with a normal pelvis.

Endometriotic lesions were classified according to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) [12]. Histological confirmation was made by pathologists. The case group (endometriotic patients) was divided into two subgroups: stage I and II of endometriosis were considered as mild endometriosis while stage III and IV were categorized as severe endometriosis. A questionnaire was completed after interview with patients and according to their medical records. The questionnaire consists of demographic data (age, education, weight, height, occupation, smoking history, exercise), menstrual and reproductive characteristics (age at menarche, menstrual pattern, duration of menstruation, dysmenorrhea, amount of menstrual bleeding, length of menstrual cycle, spotting and duration of spotting, age at first intercourse, dyspareunia, history of sexually transmitted disease [STD] and contraceptive use, age at first pregnancy and first delivery, history of live birth, ectopic pregnancy and abortion, and type and duration of infertility), abdominal mass, family history of endometriosis, pelvic pain and findings of laparoscopy.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated according to studied variables and based on the “rule of thumb” method. We considered at least 10 samples per variable; therefore sample size was estimated as 400 infertile women [13, 14]. For prevention of bias, all questionnaires were completed by the same midwife. For comparing continuous data between three groups (control, mild endometriosis and severe ones), analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied. Tukey HSD post-hoc test was used for pairwise comparison between the groups, and also χ2 test was used for qualitative data. Univariate logistic regression was performed in order to estimate the crude odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

In order to evaluate whether clinical data could predict the presence of endometriosis at laparoscopy, we used multiple logistic regression analysis. We repeated multiple logistic regression twice. First we used logistic regression to predict any type of endometriosis and then we assessed the prediction capacity of the logistic regression in order to predict patients with severe endometriosis.

We used backward logistic regression in which a p-value of 0.1 was used as the entry criterion whereas a p-value of 0.05 was considered as the threshold for a variable in order to stay in the model.

The performance of the model was assessed with the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC). An AUC of 0.5 indicates no discriminative performance, whereas an AUC of 1.0 indicates perfect discrimination.

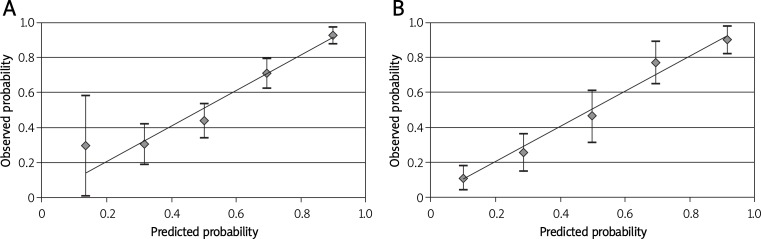

Calibration of the model was assessed by comparing the predicted probability in each category of patients with the observed percentage of endometriosis in that category. We categorized the predicted probability in 5 categories (0-20%, 20-40%, 40-60%, 60-80%, 80-100%) and in each category we compared the mean predicted probability with the observed probability in that category.

Value of p less than 0.05 was considered as significant. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or percentage.

Results

In this study, 403 infertile women who had inclusion criteria were studied. Among them, 250 subjects (62%) had endometriosis (case group) and 153 women (38%) were considered as the control group (normal pelvis). Among women with endometriosis, 52 (20.8%) were at stage I, 70 (28%) at stage II, 82 (32.8%) at stage III, and 46 (18.4%) at stage IV. Finally, according to presence and severity of endometriosis, subjects were allocated to three groups as the control group (normal pelvis) (38%), mild group (stage I or II) (30.3%), and severe endometriosis group (stage III or IV) (31.7%). There were significant differences in regard to duration of infertility, BMI, duration of menstrual bleeding, duration of menstrual cycle, duration of spotting, and age at first intercourse between these three groups by using ANOVA analysis. Chi-square analysis revealed that education status, occupational status, menstrual pattern, severity of dysmenorrheal, amount of menstrual bleeding, spotting, dyspareunia, contraceptive use, pelvic pain, abdominal mass, and family history of endometriosis were significantly different between the three groups (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences between the three groups in regard to age, type of infertility, smoking, age at menarche, dysmenorrhea, exercise, age at first pregnancy and first delivery, history of live birth, history of ectopic pregnancy, previous history of abortion, type of abortion, and history of curettage (Tables I and II). Among studied women, only 2 women had a history of STD.

Table I.

Comparison of demographic factors between case and control groups

| Variable | Levels | Control group (n = 153) | Stage I/II endometriosis (n = 122) | Stage III/IV endometriosis (n = 128) | Value of p | Crude OR* (95% CI) Any stage | Crude OR** (95% CI) Stage III/IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 30.18 ±4.37 | 30.85 ±4.53 | 31.37 ±4.79 | 0.093 | 1.047 (1.001, 1.095) | 1.059 (1.005-1.115) | |

| Type of infertility | Primary | 145 (39.0%) | 113 (30.4%) | 114 (30.6%) | 0.176 | 1† | 1† |

| Secondary | 8 (26.7%) | 8 (26.7%) | 14 (46.7%) | 1.757 (0.762-4.051) | 2.226 (0.903-5.489) | ||

| Duration of infertility [years] | 8.24 ±4.68a | 7.05 ±4.64ab | 5.96 ±4.65b | < 0.001 | 0.926 (0.886-0.967) | 0.897 (0.848-0.948) | |

| Education status [years] | < 12 | 50 (53.8%) | 27 (29.0%) | 16 (17.2%) | < 0.001 | 1† | 1† |

| 12 | 59 (39.6%) | 42 (28.2%) | 48 (32.2%) | 1.774 (1.051-2.994) | 2.542 (1.288-5.017) | ||

| > 12 | 44 (27.3%) | 53 (32.9%) | 64 (39.8%) | 3.092 (1.811-5.28) | 4.545 (2.300-8.984) | ||

| Occupational status | Housekeeper | 111 (40.7%) | 87 (31.9%) | 75 (27.5%) | 0.027 | 1† | 1† |

| Employee | 42 (32.3%) | 35 (26.9%) | 53 (40.8%) | 1.436 (0.925-2.229) | 1.868 (1.133-3.078) | ||

| BMI [kg/m2] | 26.21 ±4.20a | 24.70 ±3.87b | 23.58 ±3.62b | < 0.001 | 0.877 (0.831-0.925) | 0.830 (0.771-0.893) | |

| Smoking | Yes | 149 (37.5%) | 121 (30.5%) | 127 (32.0%) | 0.388 | 1† | 1† |

| No | 4 (66.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0.300 (0.054-1.66) | 0.293 (0.032-2.658) | ||

| Exercise | No | 108 (36.7%) | 92 (31.3%) | 94 (32.0%) | 0.663 | 1† | 1† |

| Yes | 45 (41.3%) | 30 (27.5%) | 34 (31.2%) | 0.826 (0.527-1.294) | 0.868 (0.514-1.466) | ||

| Family history of endometriosis | No | 152 (39.3%) | 121 (31.3%) | 114 (29.4%) | < 0.001 | 1† | 1† |

| Yes | 1 (6.25%) | 1 (6.25%) | 14 (87.5%) | 9.702 (1.269-74.206) | 18.667 (2.419-144.024) |

Odds ratio for comparing any type of endometriosis with control group

Odds ratio for comparing severe endometriosis patients with control group

The same letters indicate no statistical significance based on the Tukey HSD multiple comparison procedure

Reference category

Table II.

Comparison of menstrual and reproductive factors between case and control groups

| Variable | Levels | Control group (n = 153) | Stage I/II endometriosis (n = 122) | Stage III/IV endometriosis (n = 128) | Value of p | Crude OR* (95% CI) Any stage | Crude OR** (95% CI) Stage III/IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at menarche [years] | 13.42 ±1.42 | 13.62 ±1.54 | 13.22 ±1.39 | 0.089 | 0.998 (0.870-1.147) | 0.903 (0.763-1.069) | |

| Menstrual pattern | Regular | 108 (34.5%) | 97 (31.0%) | 108 (34.5%) | 0.019 | 1† | 1† |

| Irregular | 45 (50.0%) | 25 (27.8%) | 20 (22.2%) | 0.527 (0.328-0.847) | 0.444 (0.246-0.802) | ||

| Duration of menstrual bleeding [days] | 5.99 ±1.49a | 5.97 ±1.37a | 6.63 ±2.75b | 0.009 | 1.099 (0.975-1.238) | 1.178 (1.026-1.351) | |

| Dysmenorrhea | Absent | 12 (54.5%) | 3 (13.6%) | 7 (31.8%) | 0.149 | 1† | 1† |

| Present | 141 (37.0%) | 119 (31.2%) | 121 (31.8%) | 2.043 (0.86-4.849) | 1.471 (0.561-3.855) | ||

| Severity of dysmenorrhea | No pain | 12 (54.5%) | 3 (13.6%) | 7 (31.8%) | 0.031 | 1† | 1† |

| Mild | 69 (42.3%) | 54 (33.1%) | 40 (24.5%) | 1.635 (0.668-4.000) | 0.994 (0.362-2.729) | ||

| Moderate | 41 (38.0%) | 32 (29.6%) | 35 (32.4%) | 1.961 (0.778-4.944) | 1.463 (0.520-4.122) | ||

| Severe | 31 (28.2%) | 33 (30.0%) | 46 (41.8%) | 3.058 (1.199-7.800) | 2.544 (0.901-7.179) | ||

| Amount of menstrual bleeding | Low | 13 (26.5%) | 15 (30.6%) | 21 (42.9%) | 0.001 | – | – |

| Intermediate | 120 (44.9%) | 70 (26.2%) | 77 (28.8%) | 0.442 (0.224-0.872) | 0.397 (0.188-0.840) | ||

| High | 20 (23.3%) | 37 (43.0%) | 29 (33.7%) | 1.192 (0.531-2.673) | 0.898 (0.366-2.199) | ||

| Duration of menstrual cycle [days] | 29.80 ±8.83a | 28.43 ±3.56ab | 27.87 ±5.65b | 0.043 | 0.963 (0.933-0.994) | 0.963 (0.928-0.999) | |

| Spotting | No | 105 (41.2%) | 80 (31.4%) | 70 (27.5%) | 0.044 | 1† | 1† |

| Yes | 48 (32.4%) | 42 (28.4%) | 58 (39.2%) | 1.458 (0.953-2.231) | 1.812 (1.113-2.951) | ||

| Duration of spotting [days] | 0.74 ±1.37a | 0.84 ±1.36ab | 1.19 ±1.64b | 0.031 | 1.149 (0.992-1.331) | 1.222 (1.040-1.437) | |

| Age at first intercourse [years] | 20.90 ±3.91a | 22.21 ±3.93b | 23.25 ±5.48b | < 0.001 | 1.103 (1.049-1.159) | 1.114 (1.055-1.176) | |

| Dyspareunia | No | 103 (44.4%) | 63 (27.2%) | 66 (28.4%) | 0.008 | 1† | 1† |

| Yes | 50 (29.2%) | 59 (34.5%) | 62 (36.3%) | 1.932 (1.271-2.938) | 1.935 (1.193-3.140) | ||

| Contraceptive use | No | 94 (47.0%) | 57 (28.5%) | 49 (24.5%) | < 0.001 | 1† | 1† |

| Yes | 59 (29.1%) | 65 (32.0%) | 79 (38.9%) | 2.164 (1.435-3.264) | 2.569 (1.585-4.162) | ||

| Age at first pregnancy [years] | 24.25 ±4.86 | 26.48 ±4.99 | 24.84 ±5.45 | 0.227 | 1.059 (0.961-1.168) | 1.023 (0.921-1.137) | |

| History of live birth | No | 145 (38.8%) | 114 (30.5%) | 115 (30.7%) | 0.267 | 1† | 1† |

| Yes | 8 (27.6%) | 8 (27.6%) | 13 (44.8%) | 1.662 (0.717-3.852) | 2.049 (0.821-5.111) | ||

| Age at first delivery [years] | 22.5 ±5.18 | 25.75 ±3.85 | 23.0 ±4.06 | 0.274 | 1.091 (0.894-1.331) | 1.028 (0.835-1.266) | |

| Previous abortion | No | 136 (40.5%) | 96 (28.6%) | 104 (31.0%) | 0.058 | 1† | 1† |

| Yes | 17 (25.4%) | 26 (38.8%) | 24 (35.8%) | 2.000 (1.107-3.615) | 1.846 (0.943-3.614) | ||

| Type of abortion | Spontaneous | 15 (25.4%) | 23 (39.0%) | 21 (35.6%) | 1.000 | 1† | 1† |

| Induced | 2 (25.0%) | 3 (37.5%) | 3 (37.5%) | 1.023 (0.186-5.622) | 1.071 (0.159-7.221) | ||

| History of curettage | No | 145 (39.2%) | 107 (28.9%) | 118 (31.9%) | 0.065 | 1† | 1† |

| Yes | 7 (21.9%) | 15 (46.9%) | 10 (31.3%) | 2.302 (0.970-5.459) | 1.755 (0.648-4.753) | ||

| Ectopic pregnancy | No | 152 (38.5%) | 117 (29.6%) | 126 (31.9%) | 0.116 | 1† | 1† |

| Yes | 1 (12.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 2 (25.0%) | 4.379 (0.533-35.938) | 2.413 (0.216-26.918) | ||

| Pelvic pain | No | 151 (41.5%) | 108 (29.7%) | 105 (28.8%) | < 0.001 | 1† | 1† |

| Yes | 2 (5.1%) | 14 (35.9%) | 23 (59.0%) | 13.115 (3.113-55.247) | 16.538 (3.817-71.656) | ||

| Feeling of abdominal mass | No | 153 (39.6%) | 113 (29.3%) | 120 (31.1%) | 0.004 | 1† | 1† |

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (52.9%) | 8 (47.1%) | 23.009 (1.373-385.45)‡ | 21.66 (1.24-378.96)‡ |

Odds ratio for comparing any type of endometriosis with control group

Odds ratio for comparing severe endometriosis patients with control group

The same letters indicate no statistical significance based on the Tukey HSD multiple comparison procedure

Reference category

Adjusted OR for zero cell count was calculated using Agresti (2007) method [23]

Logistic regression analysis revealed that age, duration of infertility, BMI, duration of menstrual cycle, abortion history, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and family history of endometriosis are independent predictive factors for any type of endometriosis while age, education, duration of infertility, BMI, amount of menstrual bleeding, duration of menstrual bleeding, menstrual pattern, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and family history of endometriosis are independent predictive factors of severe endometriosis (Table III).

Table III.

Findings of logistic regression analysis

| Variables | Levels | Value of p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) Any stage* | Value of p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) Stage III/IV ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | – | 0.006 | 1.092 (1.026-1.0162) | 0.013 | 1.104 (1.021-1.193) |

| Education status | < 12 | – | – | – | 1† |

| 12 | – | – | 0.04 | 2.664 (1.046-6.785) | |

| > 12 | – | – | 0.051 | 2.682 (0.994-7.234) | |

| Duration of infertility [years] | – | 0.002 | 0.913 (0.861-0.968) | 0.010 | 0.900 (0.831-0.975) |

| BMI [kg/m2] | – | < 0.001 | 0.897 (0.844-0.953) | < 0.001 | 0.844 (0.772-0.925) |

| Duration of menstrual cycle [days] | – | 0.045 | 0.964 (0.931-0.999) | – | – |

| Duration of menstrual bleeding [days] | – | – | – | 0.022 | 1.196 (1.026-1.394) |

| Menstrual pattern | Regular | – | – | – | 1† |

| Irregular | – | – | 0.025 | 0.416 (0.193-0.896) | |

| Dyspareunia | No | – | 1† | – | 1† |

| Yes | 0.046 | 1.636 (1.008-2.655) | 0.038 | 1.96 (1.040-3.694) | |

| Previous abortion | No | – | 1† | – | – |

| Yes | 0.023 | 2.381 (1.130-5.017) | – | – | |

| Pelvic pain | No | – | 1† | – | 1† |

| Yes | 0.003 | 9.331 (2.131-40.352) | < 0.001 | 17.885 (3.777-84.693) | |

| Family history of endometriosis | No | – | 1† | – | 1† |

| Yes | 0.039 | 9.403 (1.125-78.633) | 0.013 | 18.563 (1.861-185.166) | |

| Amount of bleeding | Low | – | 1† | – | 1† |

| Moderate | 0.060 | 0.475 (0.219-1.031) | 0.003 | 0.210 (0.075-0.585) | |

| High | 0.879 | 1.074 (0.431-2.672) | 0.086 | 0.340 (0.090-1.167) | |

| AUC = 0.781 (0.735-0.827) | AUC = 0.855 (0.810-0.901) | ||||

Results of logistic regression for comparing any type of endometriosis with control group

Results of logistic regression for comparing severe endometriosis patients with control group

Reference category

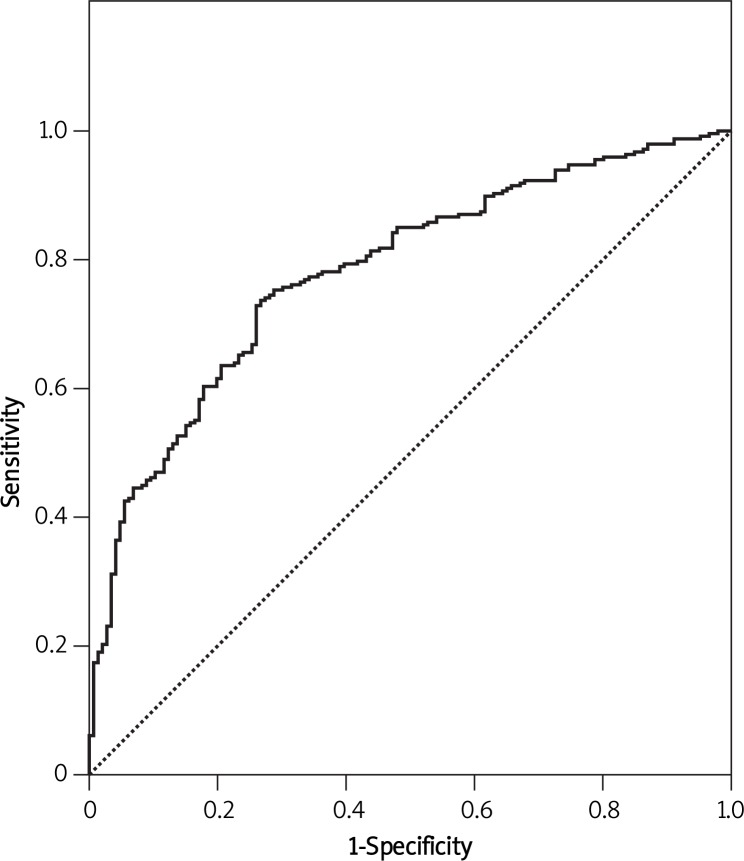

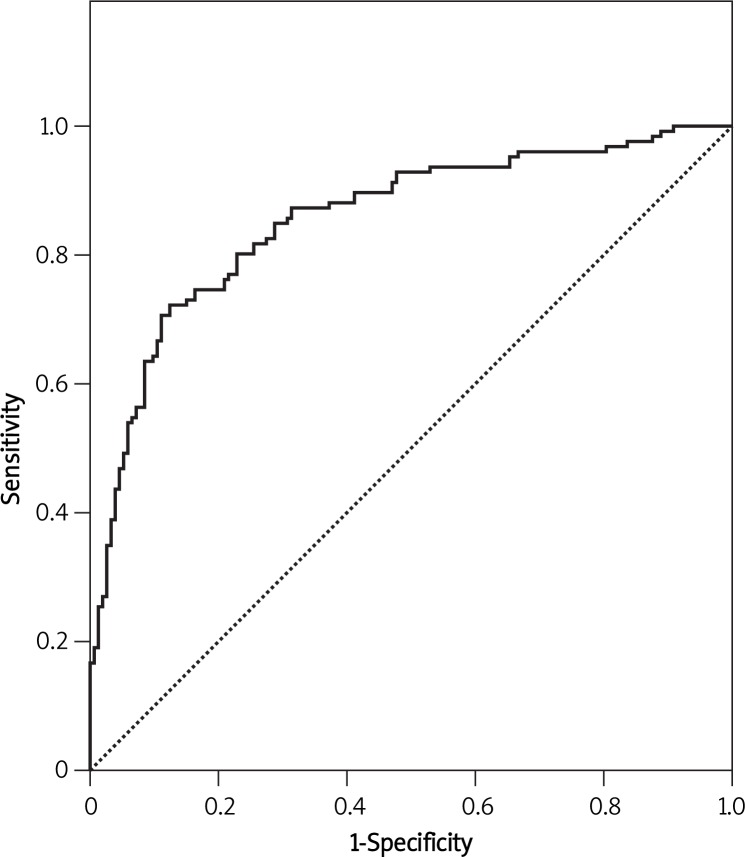

The model revealed an AUC of 0.781 with 95% CI (0.735-0.827) for predicting any type of endometriosis (Figure 1) and an AUC of 0.855 with 95% CI (0.810-0.901) for the prediction of severe endometriosis (Figure 2), both of them showing an acceptable performance. Figure 3 shows the calibration plots for any type of endometriosis and severe ones. Since the predicted probabilities and the observed rates were similar in each category, the calibration of the models is good.

Figure 1.

ROC curve of the prediction model for endometriosis

Figure 2.

ROC curve of the prediction model for severe endometriosis

Figure 3.

Calibration plot showing the association between predicted and observed probability for any type of endometriosis (A) and severe endometriosis (B)

Discussion

Several epidemiological studies have addressed biologic, reproductive and socioeconomic factors associated with endometriosis. To explore the importance of these factors in the Iranian infertile population, the present study was conducted.

Overall, the present study revealed that among studied factors, age, duration of infertility, BMI, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and family history of endometriosis could be considered as predictive factors not only for any type of endometriosis but also for severe ones. In addition, it was shown that the duration of menstrual cycle and history of abortion were affecting factors in the prediction model for any type of endometriosis while the amount and duration of menstrual bleeding, menstrual pattern and education were suggested as predictive factors for severe endometriosis.

The AUC of these prediction models was 0.781 and 0.855 for predicting any type of endometriosis and severe ones, respectively.

BMI showed an inverse correlation with endometriosis as infertile obese women were at lower risk for endometriosis (p < 0.001). This finding agreed with studies by Missmer et al. [9], Calhaz-Jorge et al. [10], an Italian group [15], Hediger et al. [16], and Bérubé et al. [17]. In addition, in the present study lower BMI was significantly associated with severity of endometriosis, which was similar to the Yi et al. [18] study. In contrast, Hemmings et al. [19] did not find any significant correlation between BMI and endometriosis. One potential explanation for this inverse relation may be the fact that an anovulatory and irregular menstrual cycle secondary to high estrogen level in obese women can lead to a reduction in retrograde bleeding.

In the present study, the duration of menstrual cycle was inversely associated with the risk of endometriosis while irregular menstrual cycle, duration, and amount of menstrual bleeding were only associated with severe endometriosis. Irregular menstrual cycle was inversely correlated while duration of bleeding was directly associated with severe endometriosis. These findings can be explained by the retrograde bleeding hypothesis as lower menstrual cycle's length and heavier bleeding could potentially increase the risk of retrograde bleeding.

Matalliotakis et al. showed that shorter cycle length and heavier menstrual cycles were associated with increasing risk of endometriosis [5]. Also other groups of researchers such as Arumugam and Lim [20], Cramer and Missmer [21] and Bérubé et al. [17] revealed that women with a menstrual cycle shorter than 27-28 days had higher risk of developing endometriosis. On the other hand, Calhaz-Jorge et al. [10], Hemmings et al. [19] and Parazzini et al. [22] did not find any significant correlation between shorter menstrual cycle and endometriosis. In addition, Mamduoh et al. [24] found that women with irregular cycles were three times more likely to develop endometriosis than women with regular cycles, which is inconsistent with our finding.

In regard to amount of bleeding, the logistic regression revealed that amount of bleeding did not have a significant association with any type of endometriosis, which was inconsistent with Calhaz-Jorge et al. [10], who reported that women with moderate to severe bleeding flow showed an increase in the risk of endometriosis as compared with women with a mild flow. One of the interesting findings in the present study was the type of relation between amount of bleeding and severe endometriosis. The model reveals that a moderate amount of bleeding (not a low amount) had the lowest risk of developing severe endometriosis, although as expected a high amount of bleeding had higher risk than moderate bleeding. One explanation of this finding may be that the amount of bleeding was categorized according to each woman's opinion in this regard and no objective measurement for menstrual blood flow was used.

In this study, age of infertile women had a direct association with any type of endometriosis and severe ones. It could be explained by the finding of Vessey et al. that endometriosis rates increased sharply from the age group 25-29 years to 40-44 and then began to fall [25]. In addition, Eskenazi and Warner found that age is the only sociodemographic characteristic which is positively correlated with endometriosis [26].

Education was the only socioeconomic factor that was found to be correlated with severe endometriosis in the present study, although this association was not found in any type of endometriosis. In agreement, an Italian group [15] and Berube et al. [17] found no relation between education and presence of endometriosis. One potential explanation for this finding may be that women with a higher educational level usually have higher socioeconomic status and higher knowledge so they pay more attention to their health and refer more and earlier than uneducated women for medical evaluation, so their disease would be diagnosed sooner and more frequently.

In the present study, family history of endometriosis was another independent factor which was directly associated with any type of endometriosis and severe one. These findings were consistent with Mamdouh et al. [24], Matalliotakis et al. [27] and Kashima et al. [28]. Cramer and Missmer, in their review article, stated that there is good evidence showing that family history increases the risk of developing endometriosis [21]. In the present study, positive family history increased the risk of developing endometriosis by 9.7 times while Mamdouh et al. found that women who had one or more relatives with endometriosis were 1.2 times more likely to develop endometriosis [24].

The present study revealed that 48.4% of women suffering from endometriosis had dyspareunia, as was previously reported (40%) by Salehpour et al. [29] in Iran. Also logistic regression analysis revealed that dyspareunia was another risk factor that had an association with any type of endometriosis and severe ones. Matalliotakis et al. [27] found that pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and dyspareunia were statistically significantly higher in women with endometriosis in comparison with infertile women without endometriosis. Calhaz-Jorge et al. [10] observed this association at a non-significant level.

Endometriosis is linked with chronic pelvic pain and infertility. The relationship between chronic pelvic pain symptoms and endometriosis is unclear because painful symptoms are frequent in women without this pathology, and because asymptomatic forms of endometriosis exist [30]. The mechanisms suggested for pain include local inflammation, adhesions, and prostaglandin production by endometriosis [31]. In the present study, 14.8% of women with endometriosis had pelvic pain, which was similar to the frequency (13.3%) reported by Salehpour et al. [29], while Matalliotakis et al. [5] reported its frequency as high as 79.1%. In addition, we found a direct relationship between pelvic pain and presence of endometriosis, which was consistent with Calhaz-Jorge et al. [10], who observed this significant association.

The present study showed that duration of infertility was inversely associated with any type of endometriosis and severe ones. This finding seems reasonable as endometriosis is a symptomatic disease with significant symptoms such as pain that forces women to refer for medical care so they will be recognized sooner.

In this study, we applied an ROC curve to assess the predictive ability of the logistic regression models. The AUCs of these prediction models were comparable with findings of the Calhaz-Jorge et al. models [10]. The AUC obtained from our models for predicting any type of endometriosis (0.781) and severe ones (0.855) showed better performance than the AUC of their models (0.71 and 0.74, respectively). The better performance of our models in infertile women may be due to the difference in the number of investigated factors and race of women.

In conclusion, according to the obtained AUCs and calibration plots in the present study, it seems that we can predict any type of endometriosis and especially severe ones by using the presented logistic regression models.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all patients enrolled in the study. We gratefully thank Dr Sedigheh Mohammadi and Dr Akram Seifollahi for their assistance.

References

- 1.Hart R. Unexplained infertility, endometriosis and fibroids. BMJ. 2003;327:721–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7417.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Houston DE, Noller KL, Melton LJ, 3rd, Selwyn BJ, Hardy RJ. Incidence of pelvic endometriosis in Rochester, Minnesota, 1970-1979. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;125:959–69. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marino JL, Holt VL, Chen C, Davis S. Life time occupational history and risk of endometriosis. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009;35:233–40. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhillon PK, Holt VL. Recreational physical activity and endometrioma risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:156–64. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matalliotakis IM, Cakmak H, Fragouli YG, Goumenou AG, Mahutte NG, Arici A. Epidemiological characteristics in women with and without endometriosis in the Yale series. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277:389–93. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witz CA, Burns WN. Endometriosis and infertility: is there a cause and effect relationshps? Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2002;53(suppl 1):2–11. doi: 10.1159/000049418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melis GB, Ajossa S, Guerriero S, et al. Epidemiology and diagnosis of endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;734:352–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb21765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szubert M, Suzin J, Wierzbowski T, Kowalczyk-Amico K. CA-125 concentration in serum and peritoneal fluid in patients with endometriosis – preliminary results. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8:504–8. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.29407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Marshall LM, Hunter DJ. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784–96. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calhaz-Jorge C, Mol BW, Nunes J, Costa AP. Clinical predictive factors for endometriosis in a Portuguese infertile population. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2126–31. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Migliaretti G, Deltetto F, Delpiano EM, et al. Spatial analysis of the distribution of endometriosis in northwestern Italy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2012;73:135–40. doi: 10.1159/000332367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berek JS. Berek & Novak's Gynecology. In: D'Hooghe TM, Hill JA, editors. Endometriosis. USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 1138–73. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1373–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vittinghoff E, Relaxing CE. The rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:710–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio dell’ endometriosi Risk factors for pelvic endometriosis in women with pelvic pain or infertility. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;83:195–9. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00332-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hediger ML, Hartnett HJ, Louis GM. Association of endometriosis with body size and figure. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1366–74. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bérubé S, Marcoux S, Maheux R. Characteristics related to the prevalence of minimal or mild endometriosis in infertile women. Canadian Collaborative Group on Endometriosis. Epidemiology. 1998;9:504–10. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199809000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yi KW, Shin JH, Park MS, Kim T, Kim SH, Hur JY. Association of body mass index with severity of endometriosis in Korean women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;105:39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemmings R, Rivard M, Olive DL, et al. Evaluation of risk factors associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:1513–21. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arumugam K, Lim JM. Menstrual characteristics associated with endometriosis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:948–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb14357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cramer DW, Missmer SA. The epidemiology of endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;955:11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parazzini F, Di Cintio E, Chatenoud L, Moroni S, Mezzanotte C, Crosignani PG. Oral contraceptive use and risk of endometriosis. Italian Endometriosis Study Group. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:695–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agresti A. An introduction to categorical data analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mamdouh HM, Mortada MM, Kharboush IF, Abd-Elateef HA. Epidemiologic determinants of endometriosis among Egyptian women: a hospital-based case-control study. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2011;86:21–6. doi: 10.1097/01.EPX.0000395322.91912.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vessey MP, Villard-Mackintosh L, Painter R. Epidemiology of endometriosis in women attending family planning clinics. BMJ. 1993;306:182–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6871.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eskenazi B, Warner ML. Epidemiology of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1997;24:235–58. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matalliotakis IM, Arici A, Cakmak H, Goumenou AG, Koumantakis G, Mahutte NG. Familial aggregation of endometriosis in the Yale Series. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:507–11. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0644-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kashima K, Ishimaru T, Okamura H, et al. Familial risk among Japanese patients with endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;84:61–4. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(03)00340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salehpour S, Zhaam H, Hakimifard M, Khalili L, Azar Gashb Y. Evaluation of diagnostic visual findings at laparoscopy in endometriosis. Iran J Fertil Steril. 2007;1:123–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fauconnier A, Chapron C. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: epidemiological evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11:595–606. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Małgorzata S, Tkaczuk-Wlach J, Jakiel G. Endometriosis and pain. Prz Menopauzalny. 2012;16:60–4. [Google Scholar]