Abstract

Background

Randomized controlled efficacy trials (RCTs), the scientific gold standard, are required for regulatory approval of Alzheimer's disease (AD) interventions, yet provide limited information regarding real-world therapeutic effectiveness. Objective: To compare the nature of evidence regarding the combination of approved AD treatments from RCTs versus long-term observational controlled studies (LTOCs).

Methods

Comparisons of strengths, limitations, and evidence level for monotherapy [cholinesterase inhibitor (ChEI) or memantine] and combination therapy (ChEI + memantine) in RCTs versus LTOCs.

Results

RCTs examined highly selected populations over months. LTOCs collected data across multiple AD stages in large populations over many years. RCTs and LTOCs show similar patterns favoring combination over monotherapy over placebo/no treatment. Long-term combination therapy compared to monotherapy reduced cognitive and functional decline and delayed time to nursing home admission. Persistent treatment was associated with slower decline. While LTOCs used control groups, adjusted for multiple covariates, had higher external validity, and favorable ethical, practical and cost considerations, their limitations included potential selection bias due to lack of placebo comparisons and randomization.

Conclusions

Naturalistic LTOCs provide complementary long-term level II evidence to complement level I evidence from short-term RCTs regarding therapeutic effectiveness in AD that may otherwise be unobtainable. A coordinated strategy/consortium to pool LTOC data from multiple centers to estimate long-term comparative effectiveness, risks/benefits, and costs of AD treatments is needed.

Key Words: Comparative effectiveness, Evidence grade, Dementia treatment, Donepezil, Galantamine, Rivastigmine, Memantine, Observational trial

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a chronic and progressive disease with a course of illness that spans many years, and in some individuals can stretch to more than a decade. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) serve as the scientific gold standard for therapeutic efficacy and are required for regulatory approval of AD interventions, but are not without limitations. RCTs are often short-term studies performed in leveraged populations that cannot adequately inform about the long-term safety, risk-benefit calculus, and comparative costs of real-world clinical treatments [1,2].

Long-term naturalistic observational cohort (LTOC) studies supply level II grade evidence and can provide critical information regarding effects of treating typical patients under conditions of usual clinical care; however, they are undervalued in AD for not providing randomized level I (RCT) grade evidence [3,4]. This dilemma in clinical medicine and health policy is neither new nor unique to AD, nor was it novel in 1967 when Schwartz and Lellouch [5] elegantly analyzed these approaches and stated that ‘most therapeutic trials are inadequately formulated, and this from their earliest stages of conception … in that the trials may be aimed at the solution of one or other of two radically different kinds of problem’. They made a distinction between two different and complementary conditions and approaches, the explanatory versus pragmatic trial. The former is performed under ‘equalized’ and ‘optimized’ laboratory conditions, while the latter is performed under ‘normal’ and ‘practical’ conditions. This brief paper presents an overview of the nature of evidence with respect to comparative strengths, limitations and evidence levels for RCTs versus LTOCs for the only FDA-approved treatments of AD, cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) and memantine.

Methods

We compared the evidentiary level for ChEI and/or memantine treatment studies including systematic database reviews/meta-analyses, RCTs, open-label extensions of RCTs (RCTOLEX) and observational cohort studies.

Results

RCTs across the AD severity spectrum provide level I (highest grade) evidence for 24- to 28-week on-label (FDA indication) stage-appropriate treatment efficacy and safety of ChEIs and memantine as mono- or combination therapy in AD. While the majority of these RCTs evaluated efficacy of ChEIs or memantine monotherapy [6,7,8,9,10,11,12], several have assessed efficacy of combination therapy (ChEI + memantine) [13,14]. Limitations of these RCTs include their performance under idealized conditions in highly selected samples with strict inclusion/exclusion, treatment adherence and monitoring criteria, and relatively short durations (approx. 6 months, except for two 52-week RCTs with donepezil [15,16]) relative to the course of AD dementia (approx. 5–15+ years). Despite providing further support for cognitive and functional benefits of sustained treatment with a ChEI over several years, a controversial community-based long-term RCT (AD 2000) [17] was hampered by design flaws (e.g. several on-off titrations, site-level dropout, high likelihood of selection bias, underpowered) and excessive attrition (>97% at year 3) making interpretation problematic, and the study failed to provide level I grade evidence. In response, the ongoing DOMINO-AD study [18], a long-term RCT, was launched. An important gap in the data that is to be assessed by the DOMINO-AD study is the comparison of combination therapy versus memantine alone (as well as vs. ChEI alone and vs. placebo); results from this landmark UK study are highly anticipated.

RCTOLEX studies provide level II-3 (level IIb/c) support for the benefits of sustained treatment with ChEIs for up to several years [19,20,21,22] and with memantine for 24 weeks [23]. RCTOLEX studies have additional limitations that include potential confounds due to possible effects of differential attrition, unblinding, and the absence of a control group for comparison during the open-label phase [24].

Several systematic reviews/meta-analyses, including from the Cochrane database, provide level I evidence for the short-term, on-label, and stage-appropriate efficacy of ChEIs and/or memantine in AD; these include evidence of the benefits of ChEIs [25,26] and memantine [27] in cognition, the benefits of memantine in global severity, cognition, function, and behavior [28], and quantification of small to medium standardized effect size estimates, Cohen's d of approximately 0.1–0.4, that favor ChEI treatment over placebo [29,30], and memantine or ChEI + memantine combination over placebo [28] in AD.

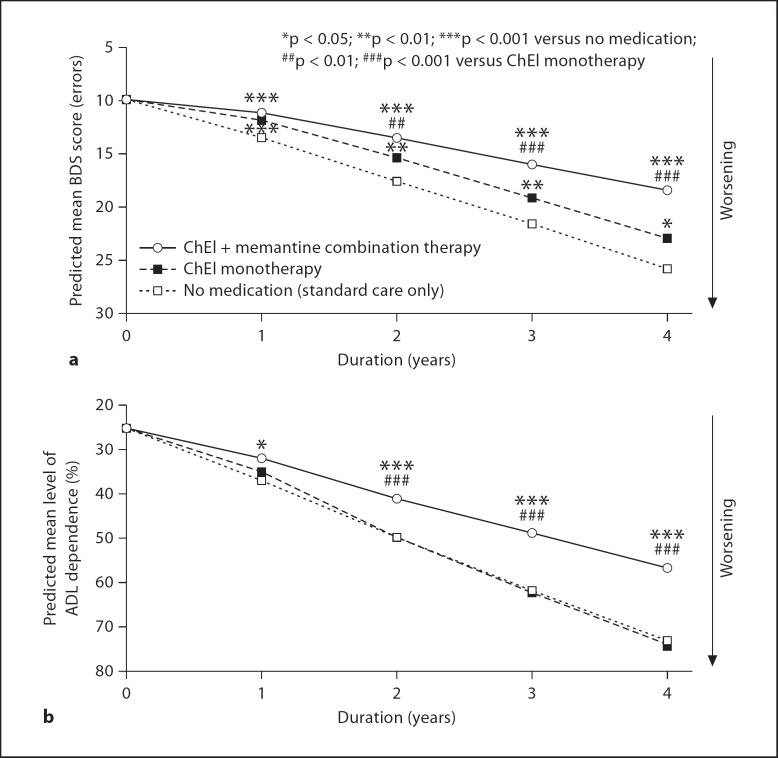

In comparison with data from the above studies, prospectively collected data from several naturalistic LTOC studies of patients with AD treated in the clinical setting provide level II-1/2 (level IIa/b) evidence for the effectiveness of ChEIs and combination therapy (ChEI + memantine) [31,35]. Relative to RTC populations, LTOC studies include subjects with significant comorbidities, greater concomitant and neuropsychoactive medications, and imperfect treatment adherence. Naturalistic LTOC studies also include larger populations (sample size of approx. 380–950), they have no strict inclusion/exclusion criteria (other than clinical criteria for AD), longer durations (mean follow-up of approx. 2.5–4 years), assessment of measures other than those required for regulatory approval, and gather data over multiple AD stages. Overall, these studies provide evidence for sustained clinical effectiveness of ChEIs [31,34,35] and combination therapy [31], with superiority of combination therapy over time in reducing decline in cognition (fig. 1a) and function (fig. 1b) [31], delaying time to nursing home placement [32], and providing more benefit with greater persistence in treatment [31,33]. Cohen's d effect size estimates for treatment benefits of combination therapy versus ChEI monotherapy range from 0.1 to 0.5 for cognition and from 0.2 to 0.7 for daily function and increase over 4 years [31]. Limitations of these LTOC data include lack of randomization, use of control cohorts without the same start/stop dates as treatment cohorts, and lack of memantine monotherapy cohorts.

Fig. 1.

Reduction of long-term cognitive and functional decline in AD patients on combination therapy with ChEI and memantine – evidence from a naturalistic LTOC study [31]. a Trajectory of decline predicted over 4 years for groups of patients with AD starting with 10 errors on the Blessed Dementia-Information Memory Concentration scale (BDS; MMSE score of approx. 22) is lowest in the ChEI + memantine combination therapy group. b Trajectory of decline predicted over 4 years for groups of patients with AD starting with 25% dependence on the Weintraub Activities of Daily Living Scale (ADL) is lowest in the combination therapy group.

Discussion

‘Most real problems contain both explanatory and pragmatic elements, for ethical reasons. Most trials hitherto have adopted the explanatory approach without question; the pragmatic approach would have often been more justifiable’ [5]. Naturalistic LTOC studies provide this type of useful pragmatic data to assess long-term treatment effects in AD. Naturalistic LTOC studies in AD provide level II grade evidence, have a high external, ecological, content and convergent validity, and support data from short-term RCTs that ChEI and memantine combination is superior to ChEI alone in reducing long-term cognitive and functional decline, and delaying nursing home admission. Furthermore, LTOC studies support that benefits of ChEIs and memantine increase with persistence in therapy and over time. While short-term explanatory RCTs in AD remain a gold standard, they are a means to drug approval, not the end of assessment and discussion regarding treatment benefits and safety. Ethical considerations must take precedence over trial design, practical considerations will follow; as such, LTOC studies provide important information that may otherwise be impractical to obtain.

LTOC data complement data from RCTs and can iteratively inform their design and implementation. Strengths of LTOC data relative to RCTs include high validity, lower cost, greater power (larger sample sizes and durations), better capacity to assess questions of practical importance, and ethical and practical favorability. Limitations of LTOC data include the fact that drug therapy is often not assigned randomly, so uncontrolled variables related to disease severity and/or duration of symptoms, perceived benefits from treatment, or other unmeasured factors may influence observed relationships between drug use and outcomes; that selection factors associated with long-term drug exposure cannot be ruled out as alternative explanations for findings, and that models can adjust for baseline differences and interactions of baseline variables with time, yet these adjustments may not fully control for potential confounding factors.

In summary, naturalistic LTOC studies are important, provide ancillary support, and should be utilized in the long-term process of therapeutic discovery and assessment including monitoring (pharmacovigilance) of long-term risk-benefit calculus to society. The integration of databases that can examine large cohorts of treated AD patients will provide invaluable information about the clinical trajectory of AD, improve prognostication, and inform clinical RCT design and therapeutic efforts in AD.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIA K23AG027171 (Atri) and NIA P50AG05133 (Lopez).

References

- 1.Godwin M, Ruhland L, Casson I, MacDonald S, Delva D, Birtwhistle R, Lam M, Seguin R. Pragmatic controlled clinical trials in primary care: the struggle between external and internal validity. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothwell PM. External validity of randomised controlled trials: ‘To whom do the results of this trial apply?’. Lancet. 2005;365:82–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17670-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Preventive Services Task Force . Guide to Clinical Preventive Services: Report of the US Preventive Services Task Force. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1989. p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Levels of Evidence. 2009, 2011.

- 5.Schwartz D, Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutical trials. J Chronic Dis. 1967;20:637–648. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(67)90041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosler M, Anand R, Cicin-Sain A, Gauthier S, Agid Y, Dal-Bianco P, Stahelin HB, Hartman R, Gharabawi M. Efficacy and safety of rivastigmine in patients with Alzheimer's disease: international randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1999;318:633–638. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7184.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peskind ER, Potkin SG, Pomara N, Ott BR, Graham SM, Olin JT, McDonald S. Memantine treatment in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: a 24-week randomized, controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:704–715. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000224350.82719.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reisberg B, Doody R, Stoffler A, Schmitt F, Ferris S, Mobius HJ. Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1333–1341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Dyck CH, Schmitt FA, Olin JT. A responder analysis of memantine treatment in patients with Alzheimer disease maintained on donepezil. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:428–437. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203151.17311.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakchine S, Loft H. Memantine treatment in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled 6-month study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;13:97–107. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-13110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers SL, Farlow MR, Doody RS, Mohs R, Friedhoff LT. A 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Donepezil Study Group. Neurology. 1998;50:136–145. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilcock GK, Lilienfeld S, Gaens E. Efficacy and safety of galantamine in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: multicentre randomised controlled trial. Galantamine International-1 Study Group. BMJ. 2000;321:1445–1449. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7274.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tariot PN, Farlow MR, Grossberg GT, Graham SM, McDonald S, Gergel I. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:317–324. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porsteinsson AP, Grossberg GT, Mintzer J, Olin JT. Memantine treatment in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease already receiving a cholinesterase inhibitor: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5:83–89. doi: 10.2174/156720508783884576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winblad B, Engedal K, Soininen H, Verhey F, Waldemar G, Wimo A, Wetterholm AL, Zhang R, Haglund A, Subbiah P. A 1-year, randomized, placebo-controlled study of donepezil in patients with mild to moderate AD. Neurology. 2001;57:489–495. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohs RC, Doody RS, Morris JC, Ieni JR, Rogers SL, Perdomo CA, Pratt RD. A 1-year, placebo-controlled preservation of function survival study of donepezil in AD patients. Neurology. 2001;57:481–488. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Courtney C, Farrell D, Gray R, Hills R, Lynch L, Sellwood E, Edwards S, Hardyman W, Raftery J, Crome P, Lendon C, Shaw H, Bentham P. Long-term donepezil treatment in 565 patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD2000): randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2105–2115. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16499-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones R, Sheehan B, Phillips P, Juszczak E, Adams J, Baldwin A, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Barber B, Bentham P, Brown R, Burns A, Dening T, Findlay D, Gray R, Griffin M, Holmes C, Hughes A, Jacoby R, Johnson T, Knapp M, Lindesay J, McKeith I, McShane R, Macharouthu A, O’Brien J, Onions C, Passmore P, Raftery J, Ritchie C, Howard R. DOMINO-AD protocol: donepezil and memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease – A multicentre RCT. Trials. 2009;10:57. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grossberg G, Irwin P, Satlin A, Mesenbrink P, Spiegel R. Rivastigmine in Alzheimer disease: efficacy over two years. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:420–431. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.4.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyketsos CG, Reichman WE, Kershaw P, Zhu Y. Long-term outcomes of galantamine treatment in patients with Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:473–482. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.5.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Truyen L, Kershaw P, Damaraju CV. The cognitive benefits of galantamine are sustained for at least 36 months: a long-term extension trial. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:252–256. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doody RS, Geldmacher DS, Gordon B, Perdomo CA, Pratt RD. Open-label, multicenter, phase 3 extension study of the safety and efficacy of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:427–433. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reisberg B, Doody R, Stoffler A, Schmitt F, Ferris S, Mobius HJ. A 24-week open-label extension study of memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:49–54. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khang P, Weintraub N, Espinoza RT. The use, benefits, and costs of cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's dementia in long-term care: are the data relevant and available? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5:249–255. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000131500.41375.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birks J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:CD005593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Jones RW, Schwam E, Wilkinson D, Waldemar G, Feldman HH, Zhang R, Albert K, Schindler R. Rates of cognitive change in Alzheimer disease: observations across a decade of placebo-controlled clinical trials with donepezil. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:357–364. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31819cd4be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McShane R, Areosa Sastre A, Minakaran N. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:CD003154. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Winblad B, Jones RW, Wirth Y, Stoffler A, Mobius HJ. Memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24:20–27. doi: 10.1159/000102568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Kaufer DI. Functional outcomes of drug treatment in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drugs Aging. 2007;24:155–167. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200724020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rockwood K, Black SE, Robillard A, Lussier I. Potential treatment effects of donepezil not detected in Alzheimer's disease clinical trials: a physician survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:954–960. doi: 10.1002/gps.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atri A, Shaughnessy LW, Locascio JJ, Growdon JH. Long-term course and effectiveness of combination therapy in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22:209–221. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31816653bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopez OL, Becker JT, Wahed AS, Saxton J, Sweet RA, Wolk DA, Klunk W, Dekosky ST. Long-term effects of the concomitant use of memantine with cholinesterase inhibition in Alzheimer disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:600–607. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.158964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rountree SD, Chan W, Pavlik VN, Darby EJ, Siddiqui S, Doody RS. Persistent treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors and/or memantine slows clinical progression of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2009;1:7. doi: 10.1186/alzrt7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wattmo C, Wallin AK, Londos E, Minthon L. Predictors of long-term cognitive outcome in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2011;3:23. doi: 10.1186/alzrt85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wattmo C, Wallin AK, Londos E, Minthon L. Long-term outcome and prediction models of activities of daily living in Alzheimer disease with cholinesterase inhibitor treatment. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25:63–72. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f5dd97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]