Abstract

Objective

Nonobstetric surgery occurs in 1–2/1000 pregnancies. Appendectomy and cholecystectomy are the two most common nonobstetric surgeries performed in pregnant women. The objective of this retrospective cohort study was to utilize the data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program to estimate major postoperative morbidity after 1) appendectomy in pregnant compared with non-pregnant women and 2) cholecystectomy in pregnant compared with non-pregnant women.

Methods

We selected a cohort of reproductive aged women undergoing appendectomy and cholecystectomy between 2005 and 2009 from the data files of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Outcomes in pregnant women were compared to those in non-pregnant women. The primary outcome was composite 30-day major postoperative complications. Pregnancy-specific complications were not assessed and thus not addressed.

Results

Pregnant and non-pregnant women had similar composite 30-day major morbidity after appendectomy (3.9% vs. 3.1%, p=0.212) and cholecystectomy (1.8% vs. 1.8%, p=0.954). Pregnant women were more likely to have preoperative systemic infections before each procedure. In logistic regression analysis, pregnancy status was not predictive of increased postoperative morbidity for appendectomy (adjusted odds ratio 1.26, 95% confidence interval 0.87–1.82).

Conclusion

Pregnancy does not increase the occurrence of postoperative maternal morbidity related to appendectomy and cholecystectomy.

Keywords: antenatal surgery, appendectomy, cholecystectomy, pregnancy, surgical outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Nonobstetric surgery is performed during the antepartum period on 1–2 out of every 1000 pregnant women. (1–3) Appendectomy and cholecystectomy are the two most common nonobstetric surgeries performed in pregnant patients. (4)

Evidence on outcomes of nonobstetric surgery in pregnancy is limited primarily to fetal and pregnancy-related complications. A systematic review accumulating 54 articles and over 12,000 nonobstetric antenatal surgeries highlights the incidence of fetal loss, prematurity, and major birth defects reported in the literature. (5) Maternal surgical outcomes after these operations are rarely reported, however, and available literature is primarily from small patient cohorts. Even fewer studies have compared postoperative outcomes in pregnant patients to those in their non- pregnant counterparts. A recent American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee Opinion acknowledges that nonobstetric surgery on the pregnant patient is an important concern for physicians who care for women and that “there are no data to allow for specific recommendations”. (6) This highlights the need for further research into maternal complications of nonobstetric surgery. Improved data regarding surgical outcomes in pregnant patients would allow for better patient counseling and improved quality of care.

The objective of this study is to utilize the data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) to estimate major postoperative morbidity after 1) appendectomy in pregnant compared with non-pregnant women and 2) cholecystectomy in pregnant compared with non-pregnant women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We analyzed data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) participant use datasets (2005–2009) to perform a retrospective cohort study. The ACS NSQIP is a national program that collects data on preoperative patient characteristics, intraoperative variables, and postoperative complications with the primary goal of enhancing surgical quality and improving patient outcomes. Participating institutions gather data on more than 130 variables on a sample of individual surgeries. Every 8 days, the first 40 patients undergoing surgical cases at each participating institution are sampled. (7) The variables collected from these patients’ charts include patient demographic and preoperative characteristics, operative procedure information, and 30-day postoperative complications. ACS NSQIP data is collected by chart review by surgical clinical reviewers, who are trained nurses at each hospital. In 2009, over 400 community and academic hospitals voluntarily participated in the ACS NSQIP. The inter-rater reliability of variables in this dataset has been demonstrated to be 97–98%, and data audits are regularly conducted to ensure the quality of the data. (8) Additional information regarding the ACS NSQIP database is available online (http://www.acsnsqip.org). The time frame of 2005–2009 was selected because these were the only years for which datasets were available. As this study was a secondary analysis of a de-identified dataset, we received exemption status in writing from the institutional review board for the Yale University School of Medicine.

Appendectomy

Our first target population included all patients who underwent appendectomy, according to the Physicians’ Current Procedural Terminology Coding System, 4th edition (CPT-4) codes listed for their primary procedure. We included patients with the following CPT-4 codes: 44900, 44950, 44960, 44970, and 44979. Definitions of these CPT-4 codes are listed in Table 1. Patients were excluded for the following reasons: 1) male gender, 2) unknown pregnancy status, 3) age greater than or equal to 51 years old or 4) previous surgical procedure within 30 days of appendectomy. No cases of concomitant appendectomy with either cesarean or vaginal delivery were identified in the dataset. The ACS NSQIP dataset does not collect information on the procedure type or the CPT-4 code of the surgical procedures performed within 30 days prior to the index procedure.

Table 1.

CPT-4 codes for appendectomy and cholecystectomy

| CPT-4 code | Appendectomy | Pregnant (n = 857) | Non-pregnant (n=19,172) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44900 | Incision and drainage of appendiceal abscess; open | 0 | 6 (0.03) |

| 44950 | Appendectomy | 277 (32.3) | 2,637 (13.7) |

| 44960 | Appendectomy; for ruptured appendix with abscess or generalized peritonitis | 35 (4.1) | 531 (2.7) |

| 44970 | Laparoscopy, surgical, appendectomy | 544 (63.5) | 15,968 (83.3) |

| 44979 | Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, appendix | 1 (0.1) | 30 (0.2) |

| CPT-4 code | Cholecystectomy | Pregnant (n = 436) | Non-pregnant (n = 32,479) |

| 47480 | Cholecystotomy or cholecystostomy, open, with exploration, drainage, or removal of calculus | 1 (0.2) | 14 (0.04) |

| 47562 | Laparoscopy, surgical; cholecystectomy | 324 (74.3) | 23,414 (72.1) |

| 47563 | Laparoscopy, surgical; cholecystectomy with cholangiography | 61 (14.0) | 7,419 (22.8) |

| 47564 | Laparoscopy, surgical; cholecystectomy with exploration of common duct | 7 (1.6) | 160 (0.5) |

| 47570 | Laparoscopy, surgical; cholecystoenterostomy | 2 (0.4) | 13 (0.04) |

| 47600 | Cholecystectomy | 29 (6.7) | 1,075 (3.3) |

| 47605 | Cholecystectomy; with cholangiography | 7 (1.6) | 267 (0.8) |

| 47610 | Cholecystectomy with exploration of common duct | 5 (1.2) | 91 (0.3) |

| 47612 | Cholecystectomy with exploration of common duct; with choledochoenterostomy | 0 | 21 (0.06) |

| 47620 | Cholecystectomy with exploration of common duct; with transduodenal sphincterotomy or sphincteroplasty, with or without cholangiography | 0 | 5 (0.02) |

All values listed as n(%)

Cholecystectomy

Our second target population included all patients who underwent cholecystectomy according to the following CPT-4 codes: 47480, 47562, 47563, 47564, 47570, 47600, 47605, 47610, 47612, and 47620. Definitions of these codes are listed in Table 1. Patients were excluded for 1) male gender, 2) unknown pregnancy status, 3) age greater than or equal to 51 years old, or 4) previous surgical procedure within 30 days of cholecystectomy. No cases of concomitant and cholecystectomy with either cesarean or vaginal delivery were identified in the dataset.

Analysis

Because our primary comparison was between women who were listed as pregnant at the time of surgery and their reproductive aged non-pregnant counterparts, all women with age greater than or equal to 51 were excluded from this study. The ACS NSQIP does not include patients younger than 16.

We examined preoperative characteristics including age, race, and ethnicity. We also explored several preoperative risk factors, including preexisting medical diseases and functional status. These preoperative risk factors and preexisting medical diseases that were analyzed are listed in Table 2 for appendectomy and Table 5 for cholecystectomy. Functional status was reported as the fraction of women who were partially or totally dependent on another person for activities of daily living (bathing, feeding, dressing, toileting, and mobility). Intraoperative variables such as operative time, type of anesthesia, and surgical approach (open or laparoscopic) were also analyzed. Unfortunately, gestational age, trimester of pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes are not recorded in the dataset.

Table 2.

Univariable analysis of preoperative predictors for major morbidity for appendectomy (N = 20,029)

| Pregnant (n=857) | Non-pregnant (n=19,172) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 27.3 ± 6.1 | 32.0 ± 9.8 | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | 571 (66.6) | 13,758(71.8) | 0.001 |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 165 (19.3) | 2,368 (12.4) | 0.001 |

|

| |||

| Current smoker | 164 (19.1) | 4,105 (21.4) | 0.112 |

|

| |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 27.9 ± 6.4 | 27.1 ± 7.2 | 0.004 |

|

| |||

| Preoperative systemic infection | 340 (39.7) | 6,448 (33.6) | <0.001 |

| SIRS | 303 (35.7) | 5,784 (30.2) | 0.001 |

| Sepsis | 36 (4.2) | 642 (3.4) | 0.177 |

| Septic Shock | 1 (0.1) | 22 (0.1) | 0.634 |

|

| |||

| Current pneumonia | 0 | 10 (0.1) | 0.646 |

|

| |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 (1.1) | 489 (2.6) | 0.006 |

|

| |||

| Hypertension | 10 (1.2) | 1,225 (6.4) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Steroid use for chronic condition | 2 (0.2) | 144 (0.8) | 0.048 |

|

| |||

| Known bleeding disorder | 7 (0.8) | 125 (0.7) | 0.560 |

|

| |||

| New or exacerbated congestive heart failure | 0 | 4 (0.0) | 0.840 |

|

| |||

| Prior myocardial infarction within 6 months | 0 | 7 (0.0) | 0.736 |

|

| |||

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention | 0 | 32 (0.2) | 0.246 |

|

| |||

| Prior cardiac surgery | 2 (0.2) | 52 (0.3) | 0.591 |

|

| |||

| Angina within 30 days of surgery | 0 | 7 (0.0) | 0.736 |

|

| |||

| New York Heart Class III or IV | 4 (0.5) | 170 (0.9) | 0.129 |

|

| |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 0 | 46 (0.2) | 0.133 |

|

| |||

| Ventilator dependency | 0 | 3 (0.0) | 0.877 |

|

| |||

| Acute or chronic dialysis | 0 | 15 (0.1) | 0.519 |

|

| |||

| Acute or chronic renal failure | 0 | 5 (0.0) | 0.804 |

|

| |||

| Ascites | 4 (0.5) | 233 (1.2) | 0.024 |

|

| |||

| Esophageal varices | 0 | 2 (0.0) | 0.916 |

|

| |||

| Current cancer | |||

| Current radiation therapy within 30 days | 0 | 5 (0.0) | 0.804 |

| Current chemotherapy within 30 days | 0 | 29 (0.2) | 0.281 |

| Known CNS tumor | 0 | 5 (0.0) | 0.804 |

| Disseminated cancer | 0 | 23 (0.1) | 0.366 |

|

| |||

| Preoperative cerebrovascular disease | |||

| Prior transient ischemic attack | 1 (0.1) | 24 (0.1) | 0.710 |

| Prior CVA without neurologic deficit | 1 (0.1) | 22 (0.1) | 0.634 |

| Prior CVA with neurologic deficit | 1 (0.1) | 36 (0.2) | 0.526 |

| Hemiplegia | 1 (0.1) | 14 (0.1) | 0.481 |

|

| |||

| Spinal Cord Injury | 1 (0.1) | 19 (0.1) | 0.583 |

|

| |||

| Unintentional weight loss of > 10% in last 6 months | 2 (0.2) | 37 (0.2) | 0.502 |

|

| |||

| Functional status (dependent/partially dependent for ADLs) | 0 | 38 (0.2) | 0.190 |

|

| |||

| Preoperative blood transfusion > 4 units | 0 | 0 | |

|

| |||

| ASA | 0.300 | ||

| Class 1 or 2 | 802 (93.6) | 18,058 (94.2) | |

| Class 3 | 55 (6.4) | 1,063 (5.5) | |

| Class 4 | 0 | 48 (0.3) | |

| Class 5 | 0 | 3 (0.0) | |

|

| |||

| Emergency procedure | 706 (82.4) | 14,161 (73.9) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Operative time | 0.834 | ||

| < 1 hour | 632 (73.8) | 14,147 (73.8) | |

| 1–2 hours | 213 (24.9) | 4,625 (24.1) | |

| 2–3 hours | 11 (1.3) | 343 (1.8) | |

| 3–4 hours | 1 (0.1) | 42 (0.2) | |

| >4 hours | 0 | 15 (0.1) | |

|

| |||

| Type of anesthesia (general) | 808 (94.3) | 19,133 (99.8) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Wound class | <0.001 | ||

| 1-Clean | 1 (0.1) | 0 | |

| 2-Clean/contaminated | 360 (42.0) | 7,642 (39.9) | |

| 3-contaiminated | 324 (37.8) | 8,612 (44.9) | |

| 4-dirty | 172 (20.1) | 2,918 (15.2) | |

|

| |||

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | 2 (0.2) | 22 (0.1) | 0.274 |

|

| |||

| Open procedure | 312 (36.4) | 3,174 (16.6) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Laparoscopic procedure | 545 (63.6) | 15,998 (83.4) | <0.001 |

All values listed as n (%) unless otherwise specified

SD = standard deviation

ADLs = activities of daily living

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists

CVA = cerebrovascular accident

SIRS = systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Table 5.

Univariable analysis of predictors for major morbidity after cholecystectomy (N = 32,915)

| Pregnant (n=436) | Non-pregnant (n=32,479) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 27.8 ± 6.5 | 35.8 ± 9.4 | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | 288 (66.1) | 22,170 (68.3) | 0.326 |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 98 (22.5) | 4,841 (14.9) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Current smoker | 100 (22.9) | 7,892 (24.3) | 0.510 |

|

| |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 31.7 ± 7.5 | 31.5 ± 8.4 | 0.707 |

|

| |||

| Preoperative systemic infection | 52 (11.9) | 1,682 (5.2) | <0.001 |

| SIRS | 49 (11.2) | 1,554 (4.8) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 3 (0.7) | 117 (0.4) | 0.213 |

| Septic Shock | 0 | 11 (0.0) | .864 |

|

| |||

| Current pneumonia | 0 | 26 (0.1) | 0.707 |

|

| |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (1.8) | 1,543 (4.8) | 0.004 |

|

| |||

| Hypertension | 12 (2.8) | 4,465 (13.8) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Steroid use for chronic condition | 1 (0.2) | 333 (1.0) | 0.063 |

|

| |||

| Known bleeding disorder | 6 (1.4) | 130 (0.4) | 0.413 |

|

| |||

| New or exacerbated congestive heart failure | 0 | 28 (0.1) | 0.688 |

|

| |||

| Prior myocardial infarction within 6 months | 0 | 11 (0.0) | 0.864 |

|

| |||

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention | 0 | 98 (0.3) | 0.270 |

|

| |||

| Prior cardiac surgery | 0 | 150 (0.5) | 0.135 |

|

| |||

| Angina within 30 days of surgery | 0 | 63 (0.2) | 0.431 |

|

| |||

| New York Heart Class III or IV | 11 (2.5) | 1,246 (3.8) | 0.155 |

|

| |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 0 | 194 (0.6) | 0.075 |

|

| |||

| Ventilator dependency | 0 | 12 (0.0) | 0.852 |

|

| |||

| Acute or chronic dialysis | 1 (0.2) | 79 (0.2) | 0.714 |

|

| |||

| Acute or chronic renal failure | 0 | 13 (0.0) | 0.841 |

|

| |||

| Ascites | 2 (0.5) | 98 (0.3) | 0.383 |

|

| |||

| Esophageal varices | 0 | 11 (0.0) | 0.864 |

|

| |||

| Current cancer | |||

|

| |||

| Current radiation therapy within 30 days | 0 | 11 (0.0) | 0.864 |

| Current chemotherapy within 30 days | 0 | 46 (0.1) | 0.541 |

| Known CNS tumor | 0 | 17 (0.1) | 0.797 |

| Disseminated cancer | 0 | 58 (0.2) | 0.461 |

|

| |||

| Preoperative cerebrovascular disease | |||

| Prior transient ischemic attack | 0 | 112 (0.3) | 0.224 |

| Prior CVA without neurologic deficit | 0 | 105 (0.3) | 0.246 |

| Prior CVA with neurologic deficit | 0 | 98 (0.3) | 0.270 |

| Hemiplegia | 0 | 67 (0.2) | 0.409 |

|

| |||

| Spinal Cord Injury | 0 | 80 (0.3) | 0.344 |

|

| |||

| Unintentional weight loss of > 10% in last 6 months | 5 (1.2) | 288 (0.9) | 0.566 |

|

| |||

| Functional status (dependent/partially dependent for ADLs) | 0 | 196 (0.6) | 0.073 |

|

| |||

| Preoperative blood transfusion > 4 units | 0 | 4 (0.0) | 0.948 |

|

| |||

| ASA | 0.252 | ||

| Class 1 or 2 | 376 (86.2) | 28,294 (87.1) | |

| Class 3 | 60 (13.8) | 4,014 (12.4) | |

| Class 4 | 0 | 169 (0.5) | |

| Class 5 | 0 | 2 (0.0) | |

|

| |||

| Emergency procedure | 92 (21.1) | 2,674 (8.2) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Operative time | 0.286 | ||

| < 1 hour | 202 (46.3) | 16,366 (50.4) | |

| 1–2 hours | 200 (45.9) | 13,287 (40.9) | |

| 2–3 hours | 27 (6.2) | 2,147 (6.6) | |

| 3–4 hours | 4 (0.9) | 475 (1.5) | |

| >4 hours | 3 (0.7) | 204 (0.6) | |

|

| |||

| Type of anesthesia (general) | 434 (99.5) | 32,436 (99.9) | 0.067 |

|

| |||

| Wound class | 0.002 | ||

| 1-Clean | 0 | 8 (0.0) | |

| 2-Clean/contaminated | 340 (79.0) | 27,010 (83.2) | |

| 3-contaiminated | 84 (19.3) | 5,097 (15.7) | |

| 4-dirty | 12 (2.8) | 364 (1.1) | |

|

| |||

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | 2 (0.5) | 76 (0.2) | 0.277 |

|

| |||

| Open procedure | 42 (9.6) | 1,473 (4.5) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Laparoscopic procedure | 394 (90.4) | 31,006 (95.5) | <0.001 |

All values listed as n (%) unless otherwise specified

SD = standard deviation

ADLs = activities of daily living

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists

CVA = cerebrovascular accident

SIRS = systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Our primary outcome was composite 30-day major morbidity. This was a composite (not exclusive) outcome of all women experiencing postoperative mortality, cardiac arrest, acute myocardial infarction, postoperative coma greater than 24 hours, cerebrovascular accident with neurologic deficit, acute renal failure, progressive renal insufficiency, deep wound surgical site infection, organ-space surgical site infection, wound dehiscence, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, prolonged mechanical ventilation greater than 48 hours, unplanned reintubation, pneumonia, sepsis, septic shock, postoperative blood transfusion, or return to the surgical operating room. Urinary tract infections and superficial surgical site infections were not considered to be major morbidity and therefore were not included in the composite outcome. A 30-day postoperative time frame was used for our composite outcome because the ACS NSQIP collects data on complications up to 30 days postoperatively.

Continuous variables were compared between cohorts using the Student’s t-test, and categorical variables were analyzed with the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. To adjust for differences in preoperative characteristics between the pregnant and non-pregnant women, a logistic regression model was constructed. Variables were selected for inclusion in the model based on univariable analysis (p<0.1). Variables were added to the model in a step-wise fashion using forward and backward selection (p<0.05). Goodness of fit of the model was verified using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p<0.05). Variables included in the final logistic regression model were assessed for potential interactions. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), PASS 2008 (NCSS, Kaysville, UT) and SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Sample size calculation

Appendectomy

We estimated the prevalence of complications after open appendectomy to be 6.1% after excluding superficial SSI and UTI. (9) We assumed a clinically meaningful difference in the occurrence of postoperative complications to be a difference of 3.0% or an increase in the occurrence of postoperative complications to 9.1%. We were limited by a finite sample size of 857 pregnant women and 19,712 non-pregnant reproductive aged women available for analysis. Our analysis achieved 91% power to detect a difference of major postoperative complications of 3.0% with a significance level (α) of 0.05 (two-sided).

Cholecystectomy

We estimated the prevalence of complications after cholecystectomy to be 3.1%. (10) We assumed a clinically meaningful difference in the occurrence of postoperative complications to be a difference of 3.0% or an increase in the occurrence of postoperative complications to 6.1%. We were limited by a finite sample size of 436 pregnant women and 32,479 non-pregnant reproductive aged women available for analysis. Our analysis achieved 88% power to detect a difference of major postoperative complications of 3.0% with a significance level (α) of 0.05 (two-sided).

RESULTS

A total of 971,455 surgical cases were available for review in the combined 2005–2009 ACS NSQIP dataset. Of these, 1,969 (0.2%) were nonobstetric procedures performed on pregnant women.

Appendectomy

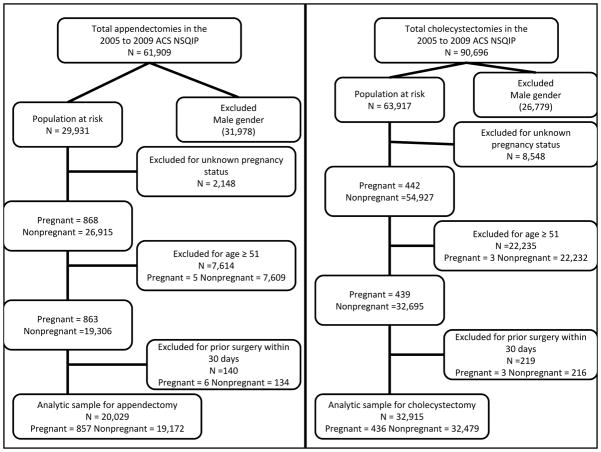

A total of 61,909 patients were identified as undergoing appendectomy based on CPT-4 coding, of which 31,978 patients were excluded for male gender. Women were excluded for the following reasons: 1) unknown pregnancy status (n=2,148), 2) age ≥51 years old (n= 7,614), and 3) prior surgical procedure within 30 days (n= 140). This left a total of 20,029 women included in our final analysis of appendectomy in women. (Figure 1) Of these cases, 857 (4.3%) involved pregnant women.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for women included in analysis of appendectomy and cholecystectomy

Results of the univariable analysis of preoperative characteristics in pregnant and non-pregnant women are presented in Table 2. Compared to non-pregnant women, pregnant women undergoing appendectomy were younger (27.3 ± 6.1 years vs. 32.0 ± 9.8 years, p<0.001), less frequently white (66.6% vs. 71.8%, p=0.001), and more frequently Hispanic (19.3% vs. 12.3%, p=0.001). The two groups were similar with respect to most preoperative medical conditions, however pregnant women had higher incidence of preoperative systemic infection (39.7% vs. 33.6%, p<0.001) and a lower incidence of diabetes mellitus (1.1% vs. 2.6%, p=0.006) and hypertension (1.2% vs. 6.4%, p<0.001) than non-pregnant women. Pregnant women underwent more emergency procedures (82.4% vs. 73.4%, p<0.001), were more likely to have types of anesthesia other than general anesthesia (5.8% vs. 0.02%, p<0.001), and more frequently had an open surgical approach compared to a laparoscopic approach (36.4% vs. 16.6%, p<0.001).

Postoperative complications in pregnant and non-pregnant women after appendectomy are presented in Table 3. Pregnant and non-pregnant women had similar composite 30-day major morbidity (3.9% vs. 3.1%, p=0.212). Additionally, the two groups had similar occurrences of all specific complications except pneumonia, which occurred more frequently in pregnant women (0.7% vs. 0.2%, p=0.004). All cases of postoperative pneumonia were observed in women who underwent general endotracheal anesthesia.

Table 3.

Major morbidity after appendectomy in pregnant and non-pregnant women (N = 20,029)

| Complication | Pregnant N = 857 | Non-Pregnant N = 19,172 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 0 | 6 (0.0) | 0.769 |

| Cardiac arrest | 0 | 0 | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 0 | 0 | |

| Postoperative coma > 24 hours | 0 | 0 | |

| Cerebrovascular accident with neurologic deficit | 0 | 0 | |

| Acute renal failure | 0 | 5 (0.0) | 0.804 |

| Progressive renal insufficiency | 1 (0.1) | 7 (0.0) | 0.295 |

| Deep wound surgical site infection | 4 (0.5) | 48 (0.3) | 0.182 |

| Organ space surgical site infection | 4 (0.5) | 235 (1.2) | 0.023 |

| Wound dehiscence | 3 (0.4) | 15 (0.1) | 0.039 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2 (0.2) | 8 (0.0) | 0.066 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 1 (0.1) | 19 (0.1) | 0.583 |

| Prolonged mechanical ventilation | 3 (0.4) | 20 (0.1) | 0.073 |

| Unplanned reintubation | 3 (0.4) | 12 (0.1) | 0.024 |

| Pneumonia | 6 (0.7) | 41 (0.2) | 0.004 |

| Sepsis | 10 (1.2) | 167 (0.9) | 0.365 |

| Septic Shock | 1 (0.1) | 19 (0.1) | 0.583 |

| Blood transfusion | 0 | 6 (0.0) | 0.769 |

| Return to the Operating Room | 14 (1.6) | 193 (1.0) | 0.076 |

| Composite Major Morbidity | 33 (3.9) | 593 (3.1) | 0.212 |

All values listed as n (%) unless otherwise specified

Blood transfusion includes the transfusion of packed red blood cells or whole blood cells within 72 hours of completion of surgery.

Return to the Operating Room includes a return to the surgical operating room for any reason within 30 days of surgery.

Superficial surgical site infections (cellulitis) and urinary tract infections were not considered as a part of composite 30-day major morbidity and not significantly different between pregnant and non-pregnant women. Superficial surgical site infections occurred in 1.52% of pregnant women and 1.36% of non-pregnant women undergoing appendectomy (p = .70). Urinary tract infections occurred in 0.7% of pregnant women and 0.71% of non-pregnant women undergoing appendectomy (p =. 98).

A logistic regression model was created incorporating preoperative characteristics as predictors of composite 30-day major morbidity. Pregnancy status was not associated with increased postoperative morbidity [Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) = 1.26 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.87–1.82)] after adjusting for age per 5 year increase [AOR = 1.17 (95% CI 1.12–1.22)], preoperative ascites [AOR = 2.31 (95% CI 1.42–3.76)], preoperative systemic infection [AOR = 2.21 (95% CI 1.88–2.60)], diabetes mellitus [AOR = 1.65 (95% CI 1.13–2.41)], and open procedure [AOR = 1.81 (95% CI 1.51–2.16)]. Results of the logistic regression model are listed in Table 4. We assessed our logistic regression model for interactions between variables. Interactions between age, ascites, and open procedures were not observed. An interaction between diabetes mellitus and preoperative systemic infection was observed with women who had diabetes mellitus more likely to have preoperative systemic infection.

Table 4.

Final logistic regression model for predictors of postoperative morbidity after appendectomy

| Adjusted OR | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy | 1.26 | (0.87, 1.82) |

| Age (per five year increase) | 1.17 | (1.12, 1.22) |

| Preoperative ascites | 2.31 | (1.42, 3.76) |

| Preoperative systemic infection | 2.21 | (1.88, 2.60) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.65 | (1.13, 2.41) |

| Open procedure | 1.81 | (1.51, 2.16) |

OR = odds ratio

Preoperative systemic infection includes 1) preoperative systemic inflammatory response syndrome, 2) preoperative sepsis, or 3) preoperative septic shock

Cholecystectomy

A total of 90,696 patients were identified as undergoing cholecystectomy based on CPT-4 coding, of which 26,779 patients were excluded for male gender. Women were excluded for the following reasons: 1) unknown pregnancy status (n = 8,548), 2) age ≥51 years old (n= 22,235), and 3) prior surgical procedure within 30 days (n= 219). This left a total of 32,915 women included in our final analysis of cholecystectomy in women. (Figure 1) Of these cases, 436 (1.3%) involved pregnant women.

Results of the univariable analysis of preoperative characteristics in pregnant and non-pregnant women are presented in Table 5. Compared to non-pregnant women, pregnant women undergoing cholecystectomy were younger (27.8 ± 6.5 years vs. 35.8 ± 9.6 years, p<0.001) and more frequently Hispanic (22.5% vs. 14.9%, p<0.001). The two groups were similar with respect to most preoperative medical conditions, however pregnant women had higher incidence of preoperative systemic infection (11.9% vs. 5.2%, p<0.001) and a lower incidence of both diabetes mellitus (1.8% vs. 4.8%, p=0.004) and hypertension (2.8% vs. 13.8%, p<0.001). Pregnant women underwent more emergency procedures (21.1% vs. 8.2%, p<0.001) and more frequently had an open surgical approach (9.6% vs. 4.5%, p<0.001).

Postoperative complications in pregnant and non-pregnant women after cholecystectomy are presented in Table 6. Pregnant and non-pregnant women had similar composite 30-day major morbidity (1.8% vs. 1.8%, p=0.954). Additionally, the two groups had similar occurrences of all specific complications. Minor complications of superficial surgical site infections and urinary tract infections were not considered as a part of the composite 30-day major morbidity and were not significantly different between pregnant and non-pregnant women. Superficial surgical site infections occurred in 1.4% of pregnant women and 1.0% of non-pregnant women undergoing cholecystectomy (p = .32). Urinary tract infections occurred in 0.9% of pregnant women and 0.6% of non-pregnant women undergoing cholecystectomy (p =. 39).

Table 6.

30 day major morbidity after cholecystectomy in pregnant and non-pregnant women (N = 32,915)

| Complication | Pregnant N = 436 | Non-Pregnant N = 32,479 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 0 | 23 (0.1) | 0.736 |

| Cardiac arrest | 0 | 14 (0.0) | 0.830 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 0 | 5 (0.0) | 0.935 |

| Postoperative coma > 24 hours | 0 | 4 (0.0) | 0.948 |

| Cerebrovascular accident with neurologic deficit | 0 | 10 (0.0) | 0.875 |

| Acute renal failure | 0 | 16 (0.0) | 0.808 |

| Progressive renal insufficiency | 0 | 10 (0.0) | 0.875 |

| Deep wound surgical site infection | 0 | 24 (0.1) | 0.726 |

| Organ space surgical site infection | 0 | 74 (0.2) | 0.372 |

| Wound dehiscence | 0 | 19 (0.1) | 0.776 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (0.2) | 25 (0.1) | 0.293 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0 | 31 (0.1) | 0.661 |

| Prolonged mechanical ventilation | 0 | 34 (0.1) | 0.635 |

| Unplanned reintubation | 0 | 45 (0.1) | 0.549 |

| Pneumonia | 0 | 64 (0.2) | 0.426 |

| Sepsis | 2 (0.5) | 111 (0.3) | 0.443 |

| Septic Shock | 0 | 42 (0.1) | 0.571 |

| Blood transfusion | 0 | 18 (0.1) | 0.787 |

| Return to the Operating Room | 6 (1.4) | 276 (0.8) | 0.236 |

| Composite Major Morbidity | 8 (1.8) | 584 (1.8) | 0.954 |

All values listed as n (%) unless otherwise specified

Blood transfusion includes the transfusion of packed red blood cells or whole blood cells within 72 hours of completion of surgery.

Return to the Operating Room includes a return to the surgical operating room for any reason within 30 days of surgery.

We were unable to conduct logistic regression exploring the effect of preoperative characteristics in pregnant and non-pregnant women on major postoperative complications after cholecystectomy due to the low frequency of pregnant women with postoperative complications. (11)

DISCUSSION

Major postoperative complications are rare in pregnant women after both appendectomy and cholecystectomy. Rates of postoperative complications among the women in this study were similar to previously reported postoperative complication rates for appendectomy (12–14) and cholecystectomy (4,10,15,16) in general populations. Additionally, our analysis indicates that the occurrence of major postoperative morbidity is similar among pregnant and non-pregnant reproductive aged women. This suggests that pregnancy alone does not significantly increase the risk of major surgical morbidity after these two procedures.

Pregnant women were significantly more likely than their non-pregnant counterparts to be diagnosed with systemic infection prior to both appendectomy and cholecystectomy. This may simply reflect that a pregnant woman’s physiologic leukocytosis, increased heart rate, and respiratory alkalosis make her more likely to meet clinical criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome than a non-pregnant woman. However, it is also possible that that the increase in preoperative systemic infection is due to a delayed diagnosis of acute appendicitis or acute cholecystitis in pregnant women due to the challenges presented by the anatomic and physiologic changes of pregnancy (17,18) combined with a reluctance to operate on pregnant women until the diagnosis is certain. Emergency procedures were significantly more common among pregnant women undergoing both appendectomy and cholecystectomy, suggesting that some degree of delayed diagnosis was present in the pregnant women studied. The higher rate of emergent cholecystectomies in the pregnant population also may be due to attempts to manage cases expectantly without surgery and defer elective procedures until after pregnancy.

We also found that pregnant women underwent more open procedures compared with non-pregnant patients. This increase in open procedures may have been due to delayed diagnosis or increased disease severity. Alternatively, the open approach may have been due to surgeons’ reluctance to perform laparoscopic procedures in pregnant women. Because neither gestational age nor specific hospital and surgeon data are available from the ACS NSQIP participant use dataset, we were unable to determine if the open approach for appendectomy and cholecystectomy was selected more often for advanced gestations or by specific providers. The increased rate of open procedures in the pregnant population did not appear to increase the risk of postoperative complications.

Kuy, et al. also compared maternal postoperative outcomes to those in non-pregnant women. This case-control analysis of cholecystectomy patients used a population-based dataset built from medical coding data, the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project-Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), to compare immediate postsurgical outcomes between 8,933 pregnant and 53,598 non-pregnant women. In multivariate analysis, pregnancy was not found to be an independent predictor for surgical complications following cholecystectomy. (4) In our analysis of the ACS NSQIP data, we similarly found no difference in major morbidity after cholecystectomy in pregnant compared to non-pregnant patients. Our study builds on that by Kuy, et al. in several important ways. First, our report adds data on appendectomy in pregnancy, aggregating information for the two most commonly performed nonobstetric antenatal surgeries. Second, by focusing on maternal morbidity rather than an array of outcomes, we were able to present an extensive list of individual complication rates for each procedure in addition to our primary outcome of composite morbidity. Finally, the database we used for our study was amassed from a comprehensive, standardized, and validated chart review process rather than from medical coding data. A systematic chart review process, by which the data used in this report were gathered, has been shown to be the most sensitive and accurate method for accruing perioperative complication data (19,20) and avoids some of the problems encountered in analyses of administrative datasets like that by Kuy, et al. (21) As demonstrated by Heisler et al., postoperative complications are much more likely to be identified through a formal chart review process, like the ACS NSQIP process, than by collecting coding data from medical billing, which substantially underestimates postoperative morbidity. (19) The comprehensive nature of the ACS NSQIP database allowed us to incorporate nineteen postoperative complications involving multiple organ systems into our composite outcome measurement. There was a non-statistically significant increase in return to the operating room in within 30 days in pregnant vs. non-pregnant women undergoing appendectomy (1.6% vs. 1.0%, p = .07) and pregnant vs. non-pregnant women undergoing cholecystectomy (1.4% vs. 0.8%, p = .24). Unfortunately, we do not have information on the CPT-4 codes of the procedures performed during the return to the operating room, therefore we cannot determine whether these follow-up procedures were for cesarean delivery.

The primary limitation of this study is that it is a secondary review of an existing dataset, and as such it is constrained by the breadth of information available. A few relevant pieces of data—specifically gestational age, pregnancy outcome, fetal wellbeing, and hospital and surgeon data—are not available in the ACS NSQIP database for analysis. Therefore we were not able to stratify by gestational age or report pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. We also were unable to account for the effect of clustering of observations within centers, though others have previously demonstrated that the clustering effect from the ACS NSQIP is minimal and does not change overall adjusted outcomes. (22,23) Additionally, due to the fact that the ACS NSQIP exclusively uses CPT-4 codes to identify patients, there is a possibility that some cases with incorrect coding were missed, and the sampling of only the first 40 patients in each 8-day cycle implies that not every case at each hospital is included in the dataset. Participation in the ACS NSQIP is voluntary, and many hospitals choose not to participate. Therefore, data from ACS NSQIP cannot be considered a representative sample of the entire United States. However, current ACS NSQIP participation includes over 400 hospitals with a wide range of both community based care facilities and tertiary care centers. This represents a steady increase of participation from 37 hospitals in 2005 to 230 hospitals in 2008 as the ACS NSQIP program continues to grow.(22) By analyzing hundreds of pregnant women undergoing appendectomy and cholecystectomy at participating centers, we were able to make a meaningful comparison of complication rates between pregnant and non-pregnant women. Our composite outcome by its nature includes postoperative complications with a wide range of severity and long-term health implications, which limits its direct clinical relevance. Given the paucity of pregnant women undergoing appendectomy and cholecystectomy, however, and given the rarity of complications after these procedures, using a composite outcome allowed an important comparison to be made with non-pregnant women. Additionally, by presenting a composite outcome that included all of the major postoperative complications included in the ACS NSQIP, we were able to present an assessment of the overall surgical morbidity of these procedures in the antenatal period.

In conclusion, we found that maternal postoperative complications are similar in pregnant and non-pregnant women after appendectomy and cholecystectomy. This study provides important information on the maternal safety of both appendectomy and cholecystectomy during pregnancy for both obstetricians and consulting surgeons caring for these women.

Acknowledgments

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the hospitals participating in the ACS NSQIP are the source of the data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

No reprints available

References

- 1.Mazze RI, Kallen B. Reproductive outcome after anesthesia and operation during pregnancy: a registry study of 5405 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161(5):1178–85. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90659-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenkins TM, Mackey SF, Benzoni EM, et al. Non-obstetric surgery during gestation: risk factors for lower birthweight. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43(1):27–31. doi: 10.1046/j.0004-8666.2003.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and use of laparoscopy for surgical problems during pregnancy. [Accessed February 8, 2011];Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) web site. 2011 Available from: http://www.sages.org/publication/id/23/

- 4.Kuy S, Roman SA, Desai R, et al. Outcomes following cholecystectomy in pregnant and nonpregnant women. Surgery. 2009;146(2):358–66. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen-Kerem R, Railton C, Oren D, et al. Pregnancy outcome following non-obstetric surgical intervention. Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):467–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 474. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:420–1. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820eede9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhungel B, Diggs BS, Hunter JG, et al. Patient and peri-operative predictors of morbidity and mortality after esophagectomy: American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP), 2005–2008. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(10):1492–501. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiloach M, Frencher SK, Jr, Steeger JE, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(1):6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page AG, Pollock JD, Perez S, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: an analysis of outcomes in 17,199 patients using ACS/NSQIP. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(12):1955–62. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingraham AM, Cohen ME, Ko CY, et al. A current profile and assessment of north american cholecystectomy: results from the american college of surgeons national surgical quality improvement program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(2):176–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, et al. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1373–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guller U, Hervey S, Purves H, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: outcomes comparison based on a large administrative database. Ann Surg. 2004;239(1):43–52. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000103071.35986.c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingraham AM, Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY. Comparison of outcomes after laparoscopic versus open appendectomy for acute appendicitis at 222 ACS NSQIP hospitals. Surgery. 2010;148(4):625–35. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen NT, Zainabadi K, Mavandadi S, et al. Trends in utilization and outcomes of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy. Am J Surg. 2004;188(6):813–20. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carbonell AM, Lincourt AE, Kercher KW, et al. Do patient or hospital demographics predict cholecystectomy outcomes? A nationwide study of 93,578 patients. Surg Endosc. 2005;19(6):767–73. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8945-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shea JA, Healey MJ, Berlin JA, et al. Mortality and complications associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 1996;224(5):609–20. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199611000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tracey M, Fletcher HS. Appendicitis in pregnancy. Am Surg. 2000;66(6):555–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Augustin G, Majerovic M. Non-obstetrical acute abdomen during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;131(1):4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heisler CA, Melton LJ, Weaver AL, et al. Determining perioperative complications associated with vaginal hysterectomy: code classification versus chart review. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209(1):119–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell PG, Malone J, Yadla S, et al. Comparison of ICD-9-based, retrospective, and prospective assessments of perioperative complications: assessment of accuracy in reporting. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14(1):16–22. doi: 10.3171/2010.9.SPINE10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grimes DA. Epidemiologic research using administrative databases: garbage in, garbage out. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1018–20. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f98300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson WG, Daley J. Design and statistical methodology of the national surgical quality improvement program: Why is it what it is? Am J Surg. 2009;198(5 Suppl):S19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen M, Dimick J, Bilimoria K, Ko C, Richards K, Hall B. Risk adjustment in the american college of surgeons national surgical quality improvement program: A comparison of logistic versus hierarchical modeling. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209(6):687–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]