Abstract

Pathological inclusions containing transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43) are common in several neurodegenerative diseases including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). TDP-43 normally localizes predominantly to the nucleus, but during disease progression, it mislocalizes to the cytoplasm. We expressed TDP-43 in rats by an adeno-associated virus (AAV9) gene transfer method that transduces neurons throughout the central nervous system (CNS). To mimic the aberrant cytoplasmic TDP-43 found in disease, we expressed a form of TDP-43 with mutations in the nuclear localization signal sequence (TDP-NLS). The TDP-NLS was detected in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus of transduced neurons. Unlike wild-type TDP-43, expression of TDP-NLS did not induce mortality. However, the TDP-NLS induced disease-relevant motor impairments over 24 weeks. We compared the TDP-NLS to a 25 kDa C-terminal proaggregatory fragment of TDP-43 (TDP-25). The clinical phenotype of forelimb impairment was pronounced with the TDP-25 form, supporting a role of this C-terminal fragment in pathogenesis. The results advance previous rodent models by inducing cytoplasmic expression of TDP-43 in the spinal cord, and the non-lethal phenotype enabled long-term study. Approaching a more relevant disease state in an animal model that more closely mimics underlying mechanisms in human disease could unlock our ability to develop therapeutics.

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases are an important problem since current medications have either limited efficacy or do not even exist. The theory behind this work is that approaching more human-like models may unlock underlying mechanisms that are missed in other systems and thus permit drug development. Animal models that better recapitulate the mechanisms in human disease will be important for validations of targets derived from lower species models and potentially for drug discovery as well. We attempted to improve upon the relevance of existing animal models for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) by expressing transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43) in the cytoplasm of spinal cord neurons, which occurs in ALS, and by inducing an overall behavioral symptomatology in rats that is more consistent with ALS. Neurodegenerative diseases are characterized and determined by both symptomatology and postmortem neuropathology. TDP-43 is a common neuropathological marker in frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) and ALS.1,2 TDP-43 is an RNA-binding and RNA-processing protein found predominantly in the nucleus, however, in FTLD and ALS, it is aberrantly found in the cytoplasm, hyperphosphorylated in ubiquitinated aggregates.1,2,3,4,5 Interestingly, the vast majority of ALS cases harbor some degree of TDP-43 pathology, in both sporadic and familial disease forms,2 so studying TDP-43 is relevant to the main form of the disease. TDP-43 pathology is also germane to a substantial fraction of the Alzheimer's disease population and other conditions such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy.4,5,6,7

There are a lot of animal models to study the role of TDP-43 in neurodegeneration (reviewed in ref. 8). Most of them are based on wild-type or mutant forms of TDP-43 that express mainly in the nucleus. One strategy that has been used to mimic the TDP-43 mislocalization to the cytoplasm that occurs in disease is to delete or mutate TDP-43's nuclear localization signal (NLS) sequence.9,10,11,12,13 We previously expressed human wild-type TDP-43 in the spinal cord of rats with a viral vector, in which case the recombinant protein was detected in the nucleus of spinal motor neurons, and severe paralysis and mortality resulted.14 In this study, we hypothesized that a form of TDP-43 with mutations in the NLS would produce ectopic expression in the cytoplasm of spinal motor neurons, based on the rationale that mimicry of relevant neuropathology will be advantageous towards approaching a more selective motor disease state relative to the overall morbidity and mortality produced by wild-type TDP-43.14 Expressing wild-type TDP-43 in transgenic mice can be embryonic lethal,15 and expressing wild-type TDP-43 with a vector in rats also led to rapid mortality in young subjects, so a longer term model with more human-like neuropathology and symptoms could provide a more relevant mechanism for research and development.

In addition to mislocalization of TDP-43 in the cytoplasm in FTLD and ALS, smaller forms of TDP-43 have been detected in disease samples including a 25 kDa species,1,3,5,10,16 which led to the theory that abnormal proteolytic cleavage of TDP-43 is involved in disease pathogenesis. The C-terminal region of TDP-43 contains a glycine-rich region that may mediate protein–protein interactions, and perhaps self-aggregation, and even prion-like spread activity during disease.17,18,19 Cell culture studies have expressed C-terminal fragments of TDP-43, which resulted in the formation of pathological inclusions,10,20,21,22,23 consistent with a role for this TDP-43 fragment in the neuropathology of the disease. We conducted a proof-of-principle study in the spinal cord of rats, hypothesizing that the TDP-25 fragment confers a specific pathogenic effect relative to the full-length TDP-43 expressed in the cytoplasm (TDP-NLS), in terms of motor deficits and aggregatory neuropathology. Rodent models are particularly germane to ALS because they encompass the anatomy of the tissues affected in ALS, the spinal cord, brainstem, and brain, and the muscles, and the functional progressive paresis to paralysis of ALS can be relevantly mimicked. We expressed several forms of TDP-43 by intravenous administration of an adeno-associated virus (AAV9) vector to newborn subjects, a method that provides consistent transduction throughout the spinal cord of mice or rats.14,24,25 Vector dose-dependence and distinguishing differences between TDP-43 isoforms in this study indicated a consistent assay.

Results

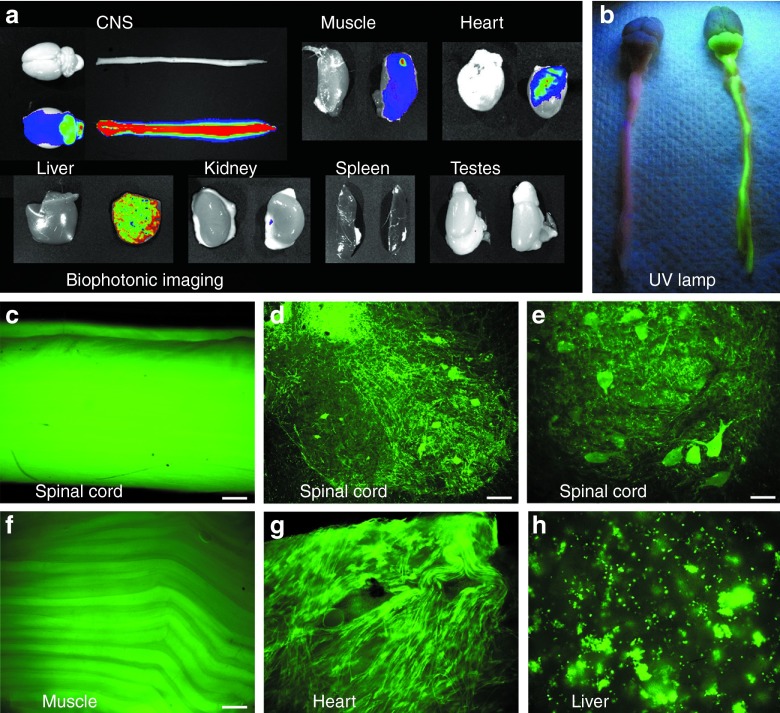

GFP expression in the control group

The AAV9 green fluorescent protein (GFP) vector used the cytomegalovirus/chicken β-actin hybrid promoter and the woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element (WPRE) for robust expression.26 The vector doses used were 2 × 1012 vector genomes (vg) or 6 × 1012 vg (high dose = 1 × 1015 vg/kg). Both doses yielded consistent transduction in several organs after intravenous vector delivery to newborn rats. Results from the high dose at 12 and 24 weeks are shown in Figure 1. The spinal cord and cerebellum are strongly transduced permitting visualization with a hand-held ultraviolet lamp (Figure 1b). The high density of GFP in the dorsal spinal cord in Figure 1a–c can largely be attributed to expression in dorsal root ganglia. Other sites of notably strong expression include muscle, heart, and liver (Figure 1). Tissues that had little to no GFP fluorescence by comparison were kidneys, spleen, testes (Figure 1), lungs, and small intestine (data not shown). We previously estimated a high transduction rate of 78% of spinal motor neurons after intravenous injections with an AAV9 GFP vector,14 and similar consistent transduction of spinal motor neurons resulted in this study (Figure 1d,e), though the visualization of the motor neurons is partially obfuscated by heavy neuropil expression. There were instances of morbidity and mortality in this experiment (described in Materials and Methods), but there was no mortality in any of the GFP rats between 2 days and their 12- or 24-week endpoints (N = 13). The growth curves for GFP rats were similar to historical data for this strain and species, and GFP rats could perform all of the motor tasks normally (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression derived from intravenous administration of an adeno-associated virus (AAV9) vector. (a) Biophotonic imaging. For each tissue shown, there is an age-matched blank control rat and a GFP rat. In the central nervous system (CNS), there is intense and uniform GFP expression in the spinal cord, with apparently less GFP in the brain. With this promoter system, there is strong expression in the muscle, heart, and liver (as shown in f–h). (b) Imaging of a GFP and control rat's spinal cord and brain by a small hand-held ultraviolet (UV) lamp. (c) View of intact dissected spinal cord from fluorescent microscope. (d,e) Lumbar spinal cord showing expression in large motor neurons in the ventral horn. a–c,f,g, 24 weeks; d,e,h, 12 weeks. Bars: in c = 536 μm; in d = 134 μm; in e = 84 μm; in f = 268 μm, in f–h same magnification.

Figure 2.

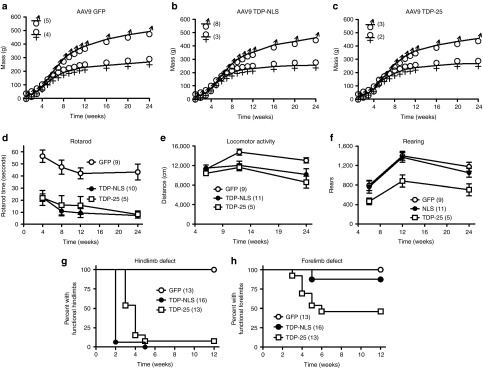

Longitudinal studies of green fluorescent protein (GFP), TDP-NLS, and TDP-25 rats over 24 weeks. One TDP-43 construct bears mutations in the nuclear localization sequence (TDP-NLS) and the other is a 25 kDa C-terminal fragment (TDP-25). (a–c) Weight gain appeared normal in the GFP group, but there were subtle effects on weight gain in the TDP-NLS and TDP-25 rats (see Results). (d) Both TDP-NLS and TDP-25 rats were impaired for the rotarod. (e) Total locomotor activity was affected in TDP-NLS and TDP-25 rats progressively over time. (f) In contrast, the rearing behavior was selectively affected in TDP-25 rats. (g,h) Observations of limb impairments. All of the TDP-NLS rats were impaired in their hindlimbs by 5 weeks, though forelimb impairment was more frequent in TDP-25 rats (7/13) versus TDP-NLS (2/16). NLS, nuclear localization signal.

Vector dose optimization for AAV9 TDP-NLS and lack of mortality

In this study, we used a stronger expression system than used previously to express wild-type TDP-43 in rats14 by including the WPRE, which boosts expression by five to tenfold.26 Thus not surprisingly, one rat injected with a dose of 2 × 1012 vg of the wild-type AAV9 TDP-43 (WPRE) showed the typical signs of TDP-43 gene transfer by 1 week: deficient growth and paralysis.14 Due to the phenotype of frozen paralysis in which breathing is barely detectable, imminent death can be predicted based on experience. This wild-type TDP-43 rat was euthanized at 13 days and recombinant TDP-43 expression in the spinal cord was confirmed by western blot (of note, in lumbar spinal cord, the specific bands for the recombinant human TDP-43 were found at 43 kDa and also 35 kDa, demonstrating the presence of smaller TDP-43 fragments when TDP-43 is overexpressed). When expressing TDP-NLS AAV9 (WPRE) at the low dose (2 × 1012 vg), weight gain was unaffected and only minor signs of limb impairments were observed in two of eight subjects by 5 weeks. Rotarod performance was unaffected by the low-dose TDP-NLS relative to dose-matched GFP rats at 4 and 8 weeks (N = 5/group, data not shown). To increase motor deficits with the TDP-NLS, we increased the vector dose to 6 × 1012 vg, which then resulted in all of the subjects in the TDP-NLS group displaying hindlimb and rotarod impairments. These data suggest that a threshold expression level was achieved at the high dose. The TDP-25 WPRE vector was run at a dose of 4.5 × 1012 vg, which only approximated the high dose, because we were limited by the titer we could achieve for this construct. Interestingly, behavioral outcomes were exacerbated in the TDP-25 subjects relative to TDP-NLS, despite using a lower dose of the AAV9 TDP-25.

In contrast to wild-type TDP-43, which induced significant mortality within 4 weeks,14 there was no mortality in the TDP-NLS group up to the 12- or 24-week endpoints (N = 16), and only one TDP-25 subject (of 13) died before its 12- or 24-week endpoint. In contrast to wild-type TDP-43, which reduced weight gain within 4 weeks,14 weight gain curves were more subtly affected by the cytoplasmic TDP-43 vectors relative to high-dose GFP controls. For example, in comparing the males from Figure 2a–c by repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), there is a main effect of vector group (F2, 28 = 22.31, P < 0.0001) but no specific timepoint differences in the Bonferroni multiple comparison tests. At 12 weeks, for which we had a larger N, there was an effect of vector group with the males by ANOVA (P < 0.05), and in the post-test, there was a difference between the GFP males and the TDP-25 males (GFP = 391 ± 9 g, N = 7; TDP-25 = 340 ± 22 g, N = 6; P < 0.05), but there was no difference with the TDP-NLS males (362 ± 8 g, N = 10) compared with either GFP or TDP-25. There was no vector group effect with the females at 12 weeks (N = 5–7/group). For both of the cytoplasmic forms of TDP-43, based on using this vector dosage and the WPRE, it is safe to say that wild-type TDP-43 is more potently toxic in terms of weight loss and mortality.14 The NLS-TDP and TDP-25 did not induce mortality like wild-type TDP-43, thus permitting long-term study.

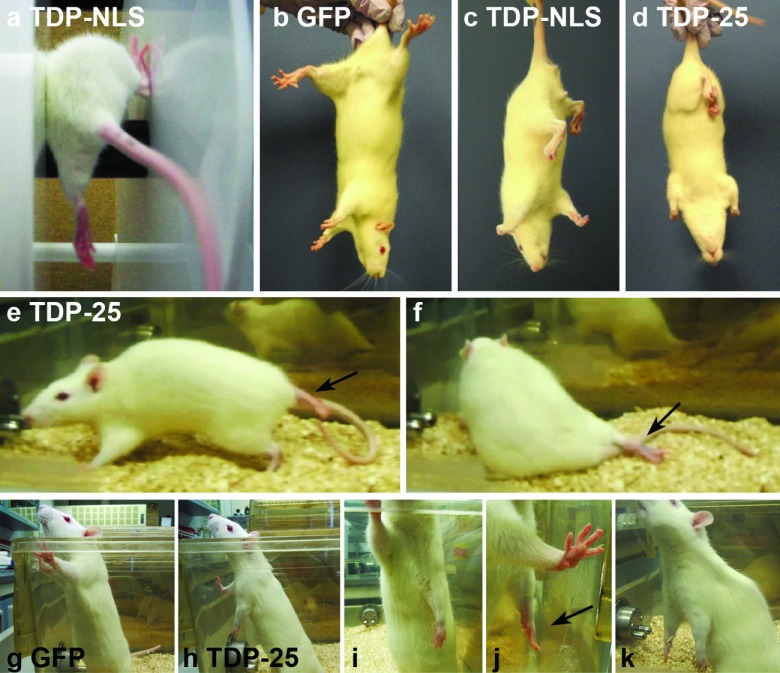

Motor impairments in TDP-NLS and TDP-25 rats

Despite the sufficient weight gain and lack of mortality, both forms of the cytoplasmic TDP-43 vectors induced consistent phenotypes of motor impairment starting as early as 2–4 weeks (Figures 2 and 3). Although no noticeable impairments were observed in the high-dose GFP controls relative to untreated rats in terms of locomotion and rearing in their cages, the NLS-TDP and TDP-25 rats displayed a variety of obvious changes in locomotion, and in the case of the TDP-25, in rearing. The dysfunction of the hindlimbs was obvious when picking up the animals by their tails and observing the escape reflex. A normal rat will extend its hindlimbs outward (Figure 3b, Supplementary Video S1). In contrast to wild-type TDP-43, which was more likely to produce total hindlimb flaccidity,14 the TDP-NLS and TDP-25 rats had better preservation of muscle tone and displayed spasticity/clonus.27 In both the TDP vector groups, the hindlimbs would abnormally clench toward the midline and often begin to spasm (Figure 3c,d, Supplementary Video S2). Interestingly, some of the animals also had obvious forelimb disability when picked up by their tail: instead of reaching outward, the forelimbs/paws would clench and spasm (Figure 3c,d, Supplementary Video S3). There were some obvious abnormal traits that were only observed in the in TDP-25 rats: gaits with the hindlimb stretching up medially over the tail (Figure 3e,f, Supplementary Videos S4 and S5), attempted rearing without the use of one or both forelimbs (Figure 3g–k), and forelimbs/paws/digits extended downward with stiff muscle tone (Figure 3j, Supplementary Video S6).

Figure 3.

Limb dysfunction after gene delivery of two forms of the transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43). (a) Loss of proper hindlimb function in a TDP-NLS rat on the rotarod task. (b–d) When briefly hanging an animal upside down, the green fluorescent protein (GFP) rat shows the normal extension response, but the TDP-NLS and TDP-25 rats are impaired. (e,f) Abnormal gait in a TDP-25 rat with the hindlimb reaching across the tail (arrows). Forelimb defects were more frequently observed in TDP-25 rats. (g) Normal rearing in a GFP rat with both forepaws touching the wall. (h–k) In contrast, TDP-25 rats would attempt to rear using one or neither forepaw. Aberrant extension and spasticity of one of the forepaws/digits shown in j (arrow). In a, 4 weeks; in b–k, 12 weeks. NLS, nuclear localization signal.

Rotarod was used to quantify overall motor function of the limbs (Figure 2d). There was obvious impairment in both the TDP-NLS (Figure 3a) and the TDP-25 groups. Animals were tested at 4, 8, 12, and 24 weeks. Data from animals run up to 24 weeks (Figure 2d, N = 5–10/group) were analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA. There was an effect of vector group (F2, 84 = 57.08, P < 0.0001) and an effect of time interval (F 3, 84 = 4.14, P < 0.01) with no interaction. The Bonferroni post-tests from the repeated-measures ANOVA yielded differences between the GFP control group and either of the TDP-43 groups at each interval (P < 0.01–0.001), and no differences between TDP-NLS and TDP-25. We also collected data from additional subjects from 4 to 12 weeks (Supplementary Table S1a, N = 11–16/interval/vector group). At each interval there was a significant effect of vector group by ANOVA with P < 0.0001, and in Bonferroni multiple comparison tests at each interval, there was a difference between the GFP control group and either of the TDP-43 vector groups with P < 0.001. Both the TDP-NLS and TDP-25 groups were greatly impaired for rotarod performance at all intervals tested.

Total locomotor activity was measured from 6 to 24 weeks, and the data analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA (Figure 2e, N = 5–11/group). There was an effect of vector group (F2, 66 = 8.01, P < 0.001) and an effect of time interval (F2, 66 = 5.33, P < 0.01) with no interaction. In the post-tests, there was difference between GFP and TDP-NLS at 12 and 24 weeks (P < 0.05), a difference between GFP and TDP-25 at 24 weeks (P < 0.01), and no differences between TDP-NLS and TDP-25. Data incorporating additional subjects at 6–12 weeks are analyzed in Supplementary Table S1b, which yielded a difference between the GFP and TDP-25 groups at 12 weeks (P < 0.01).

Rearing activity was measured from 6 to 24 weeks, and the data analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA (Figure 2f, N = 5–11/group). There was an effect of vector group (F2, 66 = 13.10, P < 0.0001) and an effect of time interval (F2, 66 = 17.34, P < 0.0001) with no interaction. In contrast to the locomotor activity, in the post-tests, there were no differences between GFP and TDP-NLS, while there were differences between GFP and TDP-25 at 12 and 24 weeks (P < 0.05), and a difference between TDP-NLS and TDP-25 at 12 weeks (P < 0.05). Data incorporating additional subjects at 6–12 weeks are analyzed in Supplementary Table S1c, which yielded more robust P values at 12 weeks (P < 0.001). The rearing data were thus able to distinguish behavioral effects of TDP-NLS and TDP-25 relative both to GFP and to each other. As mentioned, we observed obviously deficient forelimb use in the TDP-25 rats when rearing in their home cages (Figure 3g–k), which likely impacted the vertical movements in the rearing scores.

We also compared the TDP-NLS and TDP-25 groups to each other in terms of the probability and timing of the appearance of hindlimb and forelimb defects with 13–16 animals per group over 12 weeks (Figure 2g,h). Limb defects never occurred in the GFP control group. Hindlimb defects were found in all 16 TDP-NLS rats by 5 weeks, whereas 12 of 13 TDP-25 rats had a hindlimb defect by 5 weeks (the one TDP-25 rat where a hindlimb defect was not recorded was still impaired for rotarod). Log-rank analysis of the two survival curves yielded a significant difference (P < 0.05) suggesting a more rapid rate of hindlimb functional loss in the TDP-NLS rats. However, there were forelimb defects in only 2 of 16 TDP-NLS rats by 12 weeks, yet in 7 of 13 TDP-25 rats by 6 weeks. The two survival curves were different (P < 0.05) suggesting greater probability of a forelimb effect in the TDP-25 rats.

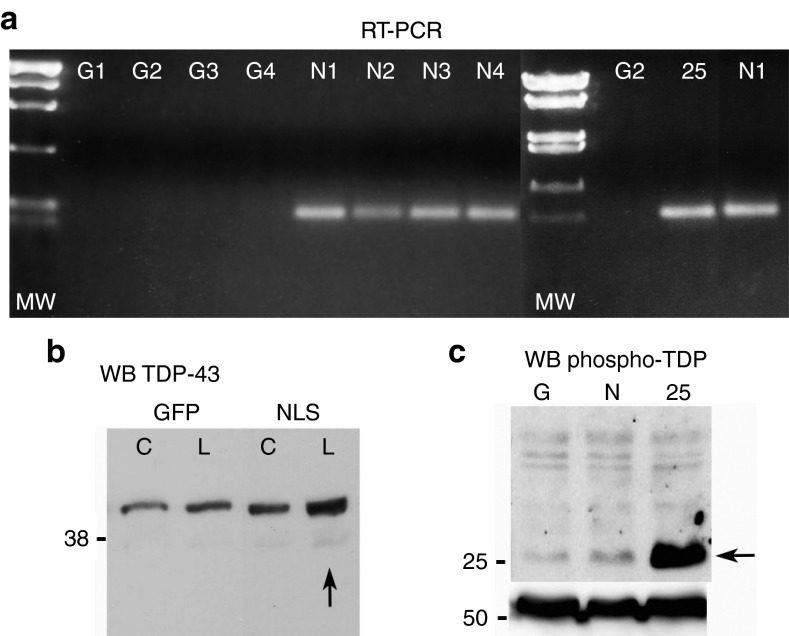

Human TDP-43 expression and cytoplasmic pathology

Before the intravenous gene transfer, TDP constructs were tested in transfected human embryonic kidney 293 cells. In stark contrast to wild-type TDP-43 which produces nuclear expression, TDP-43 immunoreactivity in the perikarya was obvious in cells transfected with the TDP-NLS DNA (Supplementary Figure S1b,c), and TDP-25 transfection caused a distinct punctate pattern (Supplementary Figure S1d). The punctuate pattern with TDP-25 is consistent with its reported proaggregatory properties.10,20,21,22,23 As expected, TDP-NLS and TDP-25 were distinguished by size on western blots using TDP-43 antibodies, a C-terminal conformational epitope antibody,10 and detection of the myc tag that was attached to the TDP-NLS. As a next step, the AAV9 constructs were injected into the rat brain, which facilitates transgene detection in a focal area, compared with the more diffuse expression from intravenous gene delivery. For the TDP-NLS AAV9, specific expression of immunoreactivity was confirmed with immunohistochemistry with antibodies against human-specific TDP-43, phospho-TDP-43, a C-terminal TDP-43 fragment,10 or the myc tag after stereotaxic injections into either the hippocampus or substantia nigra. In contrast to results with wild-type TDP-43, the TDP-NLS produced frequent cytoplasmic expression in neuronal perikarya. However, the specific TDP-NLS immunoreactivity was also prevalent in neuronal nuclei, similar to results in transgenic mice expressing a NLS deletion form of TDP-43 in the brain.12 We confirmed TDP-25 expression in vivo after stereotaxic injections by western blot and by immunohistochemistry both using the antibody against C-terminal TDP-43.10

For the intravenous injections, we used a reverse transcription-PCR method for sensitive detection of the gene transfer because the density of expression is more diffuse compared with intraparenchymal injections. RNA was isolated from the lumbar region of the spinal cord, was reverse transcribed, and the cDNA was analyzed for a human-specific TDP-43 sequence (Figure 4). GFP subjects were negative, whereas TDP-NLS and TDP-25 subjects contained the target band of the expected size. Spinal cord samples were tested for TDP-43 expression by western blot. Using a non-species–specific TDP-43 antibody that recognizes both rat and human TDP-43, we observed a consistent increase in the predicted 43–44 kDa band (Figure 4b). From two GFP subjects and two TDP-NLS subjects, we estimated a 64 and 94% elevation of TDP-43 levels with the TDP-NLS in the cervical and lumbar spinal cord, respectively. Equal protein loading was confirmed by immunoblot for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (data not shown). To attempt to determine whether the expressed TDP-NLS was phosphorylated and if smaller TDP-43 fragments were present, we used antibodies for phospho-TDP-43 and C-terminal TDP-43. We did observe several faint bands specifically in TDP-NLS samples compared with GFP controls with these antibodies (at 15, 20, 25, 43, and 80 kDa), although detection of these bands was inconsistent. Elevated expression of a 25 kDa TDP band was unequivocal in the TDP-25 group relative to GFP and TDP-NLS using a phospho-TDP antibody (Figure 4c), supporting TDP-25 hyperphosphorylation. This TDP-43 fragment has been shown to be phosphorylated in cell culture experiments previously,10 and this post-translational modification is thought to be a contributing mechanism in disease.28

Figure 4.

TDP-NLS and TDP-25 transgene expression. (a) RNA was extracted from lumbar spinal cord and probed for a sequence specific to the C-terminus of human TDP-43 mRNA. Four green fluorescent protein (GFP) rats (G1-4) were blank for the human TDP-43 sequence, and four TDP-NLS rats (N1-4) expressed the target band. The target sequence is also within the TDP-25 sequence and was detected in a TDP-25 rat (25). Different molecular weight (MW) markers were used in the two panels. (b) Western blot for TDP-43 with a non-species–specific antibody. There was a consistent one- to twofold upregulation in the TDP-NLS group in the cervical (C) and lumbar (L, arrow) spinal cord for 12 weeks. (c) The TDP-25 fragment could be selectively expressed and detected using a phospho-specific TDP-43 antibody (from M.A.G.). An immunoblot for tubulin below confirms similar protein loading. GFP and TDP-NLS, 12 weeks; TDP-25, 6 weeks. NLS, nuclear localization signal; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-PCR.

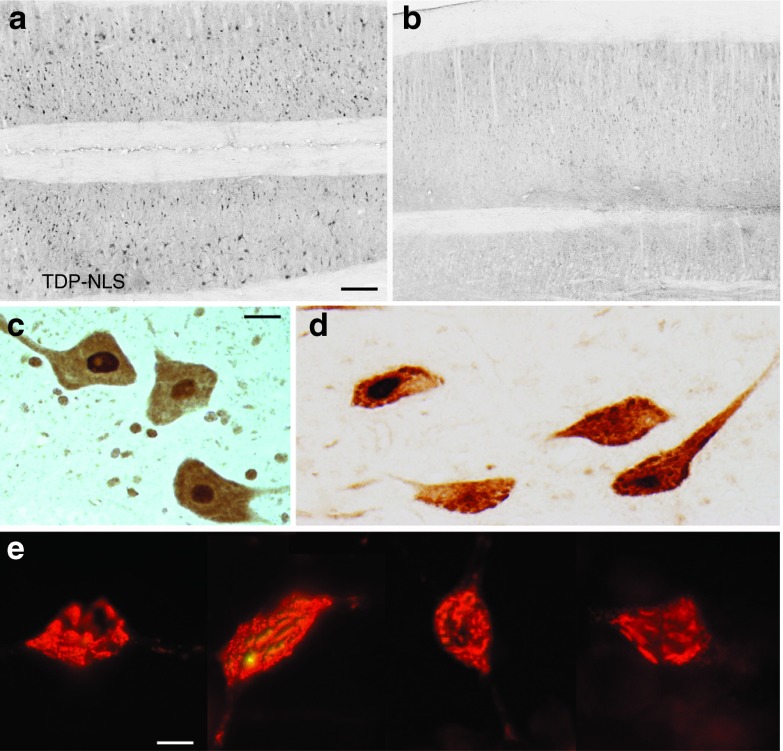

Consistent with the reverse transcription-PCR and western blot expression data, we detected TDP-43 immunoreactivity in neuronal perikarya in the TDP-NLS group using a human-specific TDP-43 antibody. An example of efficient expression in the spinal cord is shown in Figure 5a. We achieved widespread expression in the spinal cord, but noted that the human TDP-NLS also expresses in neuronal nuclei (Figure 5c,d), as we found with stereotaxic brain injections of the AAV9 TDP-NLS. Since the wild-type TDP-43 produces little to no cytoplasmic expression, the TDP-NLS is clearly successful in increasing cytoplasmic expression, though not exclusive to the cytoplasm. Specific immunoreactivity was also evident in spinal neurons in the TDP-NLS groups using antibodies against phospho-TDP-43 or a C-terminal TDP-43 fragment.

Figure 5.

Human-specific TDP-43 expression in the spinal cord with the TDP-NLS AAV9. (a) Widespread expression of cytoplasmic TDP-43 immunoreactivity was successfully achieved, demonstrated on this horizontal section of the ventral horn of the lumbar region at a 24-week interval. (b) Background staining from a matching green fluorescent protein control sample stained with the human TDP-43–specific antibody. (c,d) Twelve- and 24-week samples of spinal motor neurons expressing the human TDP-43 in the cytoplasm. There was a trend towards a more granular staining pattern at the later interval. (e) Examples of hippocampal neurons in the brain expressing the human TDP-43, after a stereotaxic injection of the TDP-NLS AAV9, 2 weeks earlier (immunofluorescence). Some of the transduced neurons had punctuate and dystrophic staining patterns consistent with aggregation. Bars: in a = 335 μm, in a,b = same magnification; in c = 20 μm, in c,d = same magnification; in e = 9 μm. AAV, adeno-associated virus; NLS, nuclear localization signal.

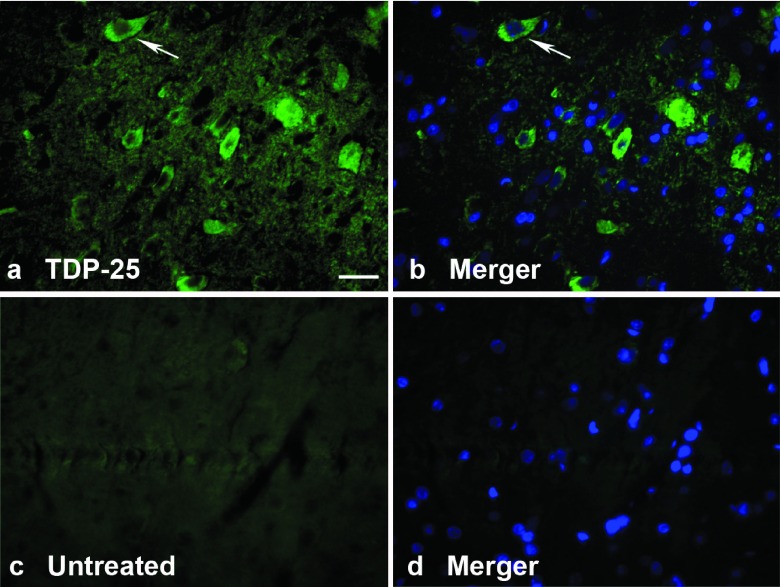

One of the main goals was to mimic human-like TDP-43 aggregates in the cytoplasm. TDP-43 staining appeared diffuse within the perikarya of lumbar lower motor neurons at 12 weeks, but there was a trend of a shift toward a more granular, punctuate staining pattern by 24 weeks (Figure 5c,d). To demonstrate human-like aggregates,29 we attempted staining with antibodies for ubiquitin and p62, but were unable to discern any evidence of ubiquitin or p62 immunopositive cytoplasmic aggregates in TDP-NLS or TDP-25 samples relative to controls. Therefore, we cannot conclude that TDP-43 aggregates were prevalent or even formed at all in the spinal cord after intravenous gene delivery. However, with the more concentrated stereotaxic brain injections, some TDP-43 aggregates can be induced with the AAV9 TDP-NLS (Figure 5e). Despite robust evidence of phospho-TDP-25 expression by western blot (Figure 4), immunohistochemical detection was more difficult, both after intravenous and stereotaxic injections. An example of specific immunoreactivity in the lumbar spinal cord from the TDP-25 group is shown in Figure 6 using a phospho-TDP-43 antibody. Interestingly, unlike the TDP-NLS, the immunoreactivity appears to be limited to the cytoplasm, but as with the TDP-NLS, we cannot conclude that TDP-25 aggregates were formed.

Figure 6.

Cytoplasmic TDP-25 expression. (a) Specific immunoreactivity for a phospho-TDP-43 antibody (green) in the cytoplasm of neurons in the lumbar spinal cord in a TDP-25 rat at 6 weeks. (b) Merger with a nuclear counterstain (DAPI, blue) demonstrates that the phospho-TDP-43 immunoreactivity is not expressed in the nucleus, arrows. (c,d) Background staining with this antibody from an untreated control imaged under matching conditions to a,b. Bars: in a = 34 μm, a–d = same magnification. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

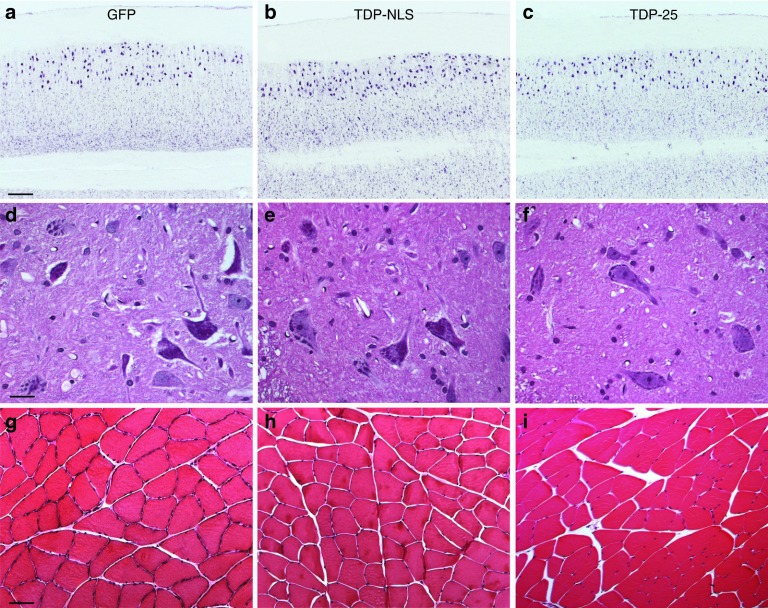

To help explain the cause of the behavioral phenotypes, we examined spinal neurons from the lumbar region and samples from the medial gastrocnemius muscle, but no obvious loss of motor neurons or muscle wasting was found (Figure 7). For motoneurons, we stained for Nissl substance (Figure 7a–c) and discriminated them by size with an imaging program, but did not find differences by ANOVA in the number of lumbar motoneurons (GFP = 220 ± 11; TDP-NLS = 199 ± 6; TDP-25 = 237 ± 14) or their size (GFP = 765 ± 24 μm2; TDP-NLS = 807 ± 13 μm2; TDP-25 = 847 ± 26 μm2) with five subjects per group at 24 weeks. Consistent with these findings, large ventral horn motor neurons appeared normal across groups (Figure 7d–f). The muscle samples also appeared basically normal across groups at 24 weeks (Figure 7g–i).

Figure 7.

Lack of neuronal loss or severe muscle atrophy at 24 weeks. (a–c) Horizontal sections of green fluorescent protein (GFP), TDP-NLS, and TDP-25 samples of the ventral part of the lumbar spinal cord stained for Nissl substance. The large motor neurons are preserved in the TDP-NLS and TDP-25 groups. (d–f) Ventral horn including motor neurons from each group stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). (g–i) Gastrocnemius muscle from each group stained with H&E. The sample from the TDP-NLS group suggested slight angulation of muscle fibers. Bars: in a = 335 μm, a–c = same magnification; in d = 21 μm, d–f = same magnification; in g = 67 μm, g–i = same magnification. NLS, nuclear localization signal.

Discussion

Expressing TDP-43 in the nucleus is toxic in terms of causing rapid weight loss and mortality. With two forms of TDP-43 that produce expression in the cytoplasm, TDP-NLS or TDP-25, a long-term model of limb paralysis manifested. A more moderate model is an improvement because there will be more restorative capacity to study long-term interventions compared with when wild-type TDP-43 or TDP-43 point mutations are expressed mainly in the nucleus. Both TDP-NLS and TDP-25 rats showed obvious rotarod deficit, hindlimb paresis to paralysis with progressive effects on locomotor scores from 6 to 24 weeks, yet these subjects were able to gain weight and persist into adulthood, thus permitting a long-term motor phenotype, which is relevant to an adult onset motor disease such as ALS. Not only were we able to discern a difference between nuclear and cytoplasmic TDP-43 expression, the smaller TDP-25 fragment exacerbated the disease state relative to the full-length TDP-NLS, which further implicates the significance of this specific TDP-43 fragment in disease pathogenesis and progression in vivo.10,20,21,30 Since the more intense deficits occurred despite using a lower vector dose, we were convinced of a specific effect of the TDP-25. The ability to achieve consistent expression levels within groups, to observe a clear dose-dependence over a threefold range for the TDP-NLS group in terms of rotarod effects, and to quantify several vector group differences behaviorally convinced us that the vector-based method to model a spinal cord disease, while somewhat technical, is a powerful approach to address hypotheses about protein structure-function in a mammalian system.

Some phenotypic aspects of ALS such as spasticity and clonus27,31,32 were manifested in TDP-NLS and TDP-25 rats that were not observed wild-type TDP-43 rats, which were more likely to show limb weakness and flaccidity in our previous study. The clonus suggests upper motor neuron involvement.27 Overall the hindlimbs were more likely to be affected in either TDP group in this study, which is consistent with other animal models of ALS32 as well as our previous study.14 We observed distinct movement disorders in TDP-25 rats relative to TDP-NLS in terms of aberrant locomotor activity within their home cages and deficient forelimb use during rearing. TDP-25 rats would extend their forelimbs, paws, and digits downward during their rears. This was never observed in TDP-NLS rats, which were able to reach their forelimbs out and upward more normally during rearing. Phenotypic differences between TDP-NLS and TDP-25 were quantified for rearing and the appearance of forelimb effects. The TDP-25 approach could therefore be advantageous for a model with consistent ALS-relevant forelimb effects over an extended period versus only at the end stage. However, rotarod and locomotor distance scores in monitoring sessions were affected similarly in both the TDP-NLS and TDP-25 groups. The hindlimb deficits appeared earlier with the TDP-NLS group, and forelimb deficits and clonus did manifest in some of the members of this group (Figure 2, Supplementary Video S3). It remains unclear whether the TDP-25 confers a unique disease state as we hypothesize, or if the pronounced effects with TDP-25 are due to a slight increase in potency for inducing symptoms. The augmented effects with the TDP-25 are consistent with the theory that effects of the TDP-NLS could be mediated by processing to the TDP-25 form.

Widespread expression of TDP-NLS in the cytoplasm of spinal motor neurons was one of the main goals of the study that was achieved. However, some of the recombinant protein was also detected in neuronal nuclei. A mixture of both nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions may be found in forms of FTLD,1,2,12,30 so the mixed cytoplasmic and nuclear expression could have disease relevance. However, when wild-type TDP-43 was expressed previously by intravenous injections, it only expressed in the nucleus. Thus expressing the TDP-NLS in the cytoplasm affected the outcome, though we cannot fully rule out contributing effects of the TDP-NLS expressed in the nucleus in this study. Despite successfully achieving cytoplasmic expression of TDP-43 with the NLS mutations, we were neither able to demonstrate clear ubiquitin- or p62-positive inclusions nor was there obvious loss of lower motor neurons or muscle atrophy. While the degree of human-like TDP-43 neuropathology was therefore limited, we can conclude that TDP-43 inclusions, neuronal loss, and muscle atrophy are not necessary in causing the hindlimb and forelimb dysfunction, and that soluble TDP-43 expression in the cytoplasm does not induce neuronal loss under these experimental conditions. Without neuronal loss and muscle atrophy and clear TDP-43 inclusions, we can conclude that the spectrum of ALS was not comprehensively mimicked. However, the TDP-25 approach was advantageous for inducing pronounced behavioral effects and appeared to produce expression exclusively in the cytoplasm, and thus suggests pathogenic effects in the cytoplasm. The robust motor deficits without motor neuron loss could potentially be mediated by defects at the neuromuscular junction, which we did not analyze. While the intravenous gene delivery provides widespread expression in the CNS and a motor phenotype when TDP-43 isoforms are expressed, direct intraparenchymal injections to the CNS33 may be required to study more robust neuropathology and neuronal loss than observed here.

The extent to which transgene expression outside the CNS plays a role in the disease states remains unclear, with strong expression in muscle, heart, and liver in this system. Restricting expression to one tissue will require design changes such as promoter, AAV serotype, or route of administration, or other methods to suppress expression in specific tissues to fully delineate where the expression is necessary to induce symptoms. We believe expression in the spinal cord is critical however from pilot studies with a Tet-off inducible promoter from Haberman et al.34 Using the same gene transfer methods as in this study, in the unsuppressed state, this promoter drove expression strongly in the liver with no detectable spinal cord expression, and with wild-type TDP-43 AAV9 gene transfer in this promoter system (N = 3), there were no behavioral symptoms or weight loss, supporting that the spinal cord expression is required for the motor phenotype. Consistent with our previous study,14 the transduction pattern in the CNS was predominantly neuronal when injecting neonatal rats. A shift to more astroglial expression occurs when injecting older subjects,24 which could be significant for ALS as a way to study non-neuronal pathophysiology mechanisms.2,8,24,25

Exploring functions of TDP-43 isoforms in the cytoplasm of spinal cord neurons in vivo is an important direction given the prevalence of cytoplasmic TDP-43 pathology in ALS. The rapid nature of this vector model system can facilitate the investigation of newly discovered pathological proteins, specific pathological protein isoforms (e.g., point mutations, cleavage products, or post-transcriptionally modified), and specific co-pathologies as they continue to emerge. Our results demonstrate the utility of this approach for delineating small phenotypic differences after expressing gene variants. To address hypotheses with a variety of constructs, a vector-based system can be higher throughput than transgenic mice for valid systematic comparisons, without the constant need to produce, maintain, and genotype genetic lines and progeny. A vector approach is far more feasible than transgenics for improving disease relevance in nonhuman primates.35 In terms of inducing TDP-43 inclusions to form in future studies, a stronger expression system could be used such as self-complementary AAV vectors.36 However, early mortality could result with higher expression levels than used here, as occurs with wild-type TDP-43, which may be due to a developmental defect rather than a neurodegenerative disease state. An inducible expression system could potentially overcome confounding developmental effects. Another advantage of a vector-modeling system is the facility to combine transgenes. For example, we hypothesize TDP-43 inclusion formation could be increased by co-expressing one of the other pathological proteins found in ALS inclusions such as ubiquilin 2 or p62, that like TDP-43, may be mutated in familial forms of the disease.29,37

Expressing different forms of TDP-43 led to unique, consistent behavioral impairments, and cytoplasmic expression enabled a long-term model that is amenable for testing palliatives against either hindlimb or forelimb symptoms. The cytoplasmic TDP-43 expression appeared soluble in this study, but future approaches could induce aggregation in situ. Studying the formation of TDP-43 inclusions in the cytoplasm could help address if inclusions are necessary for neuronal loss in mammalian systems and help to develop strategies to block inclusions from forming. Relative to transgenic mice, these consistent data support that a vector-based approach can expedite hypothesis testing for a variety of protein isoform constructs.

Materials and Methods

DNAs and AAVs. The transgene expression cassette included the AAV2 terminal repeats, the hybrid cytomegalovirus/chicken β-actin promoter, the WPRE, and the bovine growth hormone polyadenylation sequence (-TR2-CBA-WPRE-pA-TR2-).26 There were separate constructs with DNA inserts for GFP, human wild-type TDP-43,33 human TDP-43 with mutations in the NLS (K82A, R83A, K84A),10 a C-terminal myc epitope tag, and a C-terminal fragment of human TDP-43 (amino acids 220-414).10 The helper and AAV9 capsid plasmids to make AAV9 were from James Wilson (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania).38 The GFP, TDP-NLS, or TDP-25 DNAs were individually packaged into AAV9 using a previously described method.39 The final stocks were sterilized by Millipore (Billerica, MA) Millex-GV syringe filters, aliquoted, and stored frozen. Encapsidated genome copies were titered by dot-blot, with all preps containing over 3 × 1013 vg/ml. Equal dose comparisons were made by normalizing titers with the diluent, Lactated Ringer's solution (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL). Over the course of the study, two batches of the GFP control, two batches of the NLS TDP-43, and four batches of the TDP-25 AAV9 vectors were tested, which yielded consistent results across batches.

Animals, timeline, dosing, vector injections. Animal use totaled 82 subjects across eight litters of Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN). Gene transfer occurred at postnatal day 1, and the animals were studied for up to 24 weeks as indicated. Both genders were used in the study. Wild-type TDP-43 AAV9 (N = 1) was run at a dose of 2 × 1012 vg. The GFP AAV9 and the NLS TDP-43 AAV9 were run at two doses: 2 × 1012 vg (8–11 rats injected/group) and 6 × 1012 vg (14–17 rats injected/group). For the high dose, this is equivalent to 1 × 1015/kg since the newborn rats typically weigh 6 g. The TDP-25 AAV9 was run at a dose of 4.5 × 1012 vg (16 rats injected), because we were limited by the titer of our TDP-25 AAV9 preps, so the high dose was only approximated in the TDP-25 group. Intravenous injections to neonatal rats were performed by a veterinarian with extensive experience (E.A.O.). A total of 100 μl of AAV9 was loaded into a 1 ml syringe coupled to a 30 gauge needle. Using a lighted magnifying glass, the temporal vein of the rat was centered between the left thumb and forefinger of the veterinarian. The syringe was aligned and bridged to the table with the right hand of the veterinarian. A proper injection causes a visible blanching of the temporal vein without any swelling (blebbing) of any tissue. Based on experience, the injection procedure is highly consistent, as are the gene transfer results upon reaching the endpoint.14 Tattoo ink (Spaulding Color, Voorheesville, NY) was gently injected into the paws by the veterinarian for identification. The pups were placed on a heating pad and under a lamp to recover before being returned to the mother cage. Weaning was at 3 weeks. All animal procedures followed protocols approved by our institutional Animal Care and Use Committee as well as the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

We experienced animal morbidity in this study using newborn animals with injections into the temporal vein. A total of eight rats died within the first 1–2 days after injection, which we attributed largely to the injection technique itself (versus a specific gene), because they were spread across dose/vector groups (2 low-dose GFP, 1 high-dose GFP, 3 low-dose TDP-NLS, 2 TDP-25), and because the motor behavior signs of TDP-43 gene transfer are not detected soon. Some degree of attrition unrelated to treatment is expected in this strain/species between birth and weaning. In addition, we observed a stubbed tail (1 low-dose GFP, 1 high-dose GFP high dose) or stubbed tail and stubbed hind digits (2 high-dose GFP, 1 high-dose TDP-NLS) in five rats, which was typically observed early on from 1 to 4 weeks and would recover. Two rats developed a subcutaneous mass on the side of their body, one at 12 weeks (TDP-25) and one at 24 weeks (high-dose TDP-NLS).

Five rats (male, 300 g) received stereotaxic injections of AAV9 vectors into the brain by previously described methods.33,39 Injections were into either the hippocampus or the substantia nigra with vector doses from 3 × 1010 to 1 × 1011 vg and with expression intervals of 2 or 3 weeks.

Behaviors. Animals were assessed for performance on several motor-related behaviors: hindlimb escape reflex, rotarod, and open field. For the hindlimb escape reflex, rats were gently raised by their tail to observe the normal outward extension of the limbs for up to 10 seconds. This was viewed during weighings from 2 to 24 weeks after gene transfer. Rotarod (Rota-rod/RS; Letica Scientific Instruments, Barcelona, Spain) testing was at 4, 8, 12, and 24 weeks. The rats were initially trained on the rotarod for 1 minute at 4 rpm. Sessions involved an accelerating rotarod from 4 to 40 rpm over 2 minutes. The time spent on the wheel before falling was averaged from three trials. Rats were tested for locomotor and rearing behaviors in a photobeam activity monitoring system (Truscan 2.0; Coulbourn Instruments, Whitehall, PA) at 6, 12, and 24 weeks after gene transfer. Trials were for 30 minutes in a dark room.

Biophotonic imaging. Rats were anesthetized with a cocktail of 3 ml xylazine (20 mg/ml; Butler, Columbus, OH), 3 ml ketamine (100 mg/ml; Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA), and 1 ml acepromazine (10 mg/ml; Boerhinger Ingelheim, St Joseph, MO) administered intramuscularly at a dose of 1 ml/kg, and then perfused with 100 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Tissues were then extracted and stored in PBS. Within 30 minutes, the brains were placed in the Xenogen IVIS 100/XFO-12 apparatus (Xenogen, Alameda, CA) and imaged with the GFP filter set.

Reverse transcription-PCR. Tissues were dissected and frozen on dry ice. Later, they were stored in 1 ml of RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX) overnight at 4 °C. Then, the tissue was homogenized in 1 ml RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX). RNA was extracted with chloroform/isopropanol, washed with ethanol, and dissolved in RNase-free water (Ambion). RNA was then further purified using the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and stored at −80 °C. The RNA concentration was measured using a spectrophotometer and the integrity was assessed by electrophoresis on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). cDNA was transcribed from 1 μg of RNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and stored at −20 °C. PCR was performed using the SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix with a CFX96 PCR Detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Cycling parameters were 50 °C for 2 minutes, 95 °C for 10 minutes, and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds followed by 60 °C for 1 minute. Reactions were run in triplicate in a 96-well fast optical plate (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and contained 20 ng of cDNA. Human-specific TDP-43 primers were chosen from a sequence in the C-terminal that is nonhomologous to rat TDP-43: sense, TAATAACCAAAACCAAGG and antisense, AGAAGACTTAGAATCCAT (purchased from Eurofins MWG Operon, Hunstville, AL). The primers target a 178 bp sequence that is present in both the NLS-TDP and TDP-25 DNAs.

Western blots. Tissues were dissected and frozen on dry ice. Later, the samples were put in RIPA buffer (1% Nonidet-P40/0.5% sodium deoxycholate/0.1% SDS/PBS) with protease inhibitors (Halt protease inhibitor cocktail kit from Pierce, Rockford, IL) and the soluble fraction was prepared by Dounce homogenization and centrifugation. Protein content was determined by Bradford assay reagents (Bio-Rad) and subjected to 12% SDS/polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad), with each gel loaded with equal protein in each lane (20–80 μg depending on the gel). The primary antibodies for immunoblots (all at 1:2,000) were TDP-43 (ProteinTech, Chicago, IL), human-specific TDP-43 antibody (Abnova, Taipei City, Taiwan), phospho-TDP-43 epitope (developed by L.P. to recognize phospho-serines 409/410), phospho-TDP-43 epitope (developed by M.A.G. to recognize phosphorylated serines 409/410 of TDP-43), C-terminal TDP conformational epitope (M2085 developed by L.P. against TDP-43 residues 220-227),10 glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Ambion), and tubulin (E7 monoclonal antibody developed by Michael Klymkowsky from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA). Secondary antibody and ECL reagents were from Amersham (Buckinghamshire, UK).

Histology/immunohistochemistry. Animals were anesthetized as above and perfused with PBS, followed by cold 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Tissues were removed and immersed in fixative overnight at 4 °C. Some of the spinal cord tissues were paraffin-embedded and coronal sections were cut (5 μm thick) by microtome and immunostained using an automated system (Biogenex I6000; Biogenex, San Ramon, CA). Other spinal cord tissues were equilibrated in a cryoprotectant solution of 30% sucrose/PBS at 4 °C, and horizontal sections (50 μm thick) were cut on a sliding microtome with a freezing stage. Primary antibodies included: human-specific TDP-43 antibody (Abnova; 1:250), phospho-TDP-43 epitope (from L.P., 1:2,000), phospho-TDP-43 epitope (from M.A.G., 1:2,000), C-terminal TDP conformational epitope (from L.P., 1:1,000), and GFP (Invitrogen; 1:500). Secondary antibodies included biotinylated antibodies from DAKO Cytomation (Carpinteria, CA; 1:2,000) and Alexa Fluor 488- or Cy3-conjugated antibodies (Invitrogen or Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, respectively; 1:300). Nissl and hematoxylin and eosin staining followed standard methods. Nissl-stained spinal lower motor neurons could be discriminated by their size using the Scion Imaging program (Scion, Fredericksburg, MD). On horizontal sections of the ventral horn in the lumbar enlargement, four non-overlapping 10X fields were analyzed per animal to estimate the number of lower motor neurons and their sizes, by an observer who was blind with respect to the treatment groups. Approximately 200 cells per animal were analyzed.

Statistics. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical tests included ANOVA or repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison post-tests, or Mantel–Cox log-rank test, as indicated.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Distinct localization patterns after transfection of wild-type TDP-43, TDP-NLS, or TDP-25. Table S1. Rotarod, locomotor, and rearing behaviors from 4 to 12 weeks. Video S1. A control GFP rat displays normal hindlimb extension and muscle tone when raised by its tail (6 weeks). Video S2. In a TDP-NLS rat, the hindlimbs do not extend properly and there is spasm in the hindlimbs (6 weeks). Video S3. In another TDP-NLS rat, the hindlimbs are dysfunctional and there is spasm in one of the forelimbs (6 weeks). Video S4. Normal walking and rearing of a GFP rat (12 weeks). Video S5. Abnormal hindlimb gait in a TDP-25 rat (12 weeks). Video S6. Abnormal rearing in a TDP-25 rat (12 weeks).

Acknowledgments

Hayley Peters, Gary Bernard, Andrew Thomas, Natalia Aladyshkina, Niki Gill, and Joseph Jones provided technical assistance. Tammy Dugas, Valeria Hebert, Yafei Xu, and Li-Ru Zhao provided technical advice. Blas Catalani, Michael Franklin, Robert Hermann, Richard Zweig, and Robert Schwendimann provided interpretation of clinical significance. The Biomedical Research Foundation of Northwest Louisiana and the Fidelity Biosciences Research Initiative supported the project. The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie IR, Bigio EH, Ince PG, Geser F, Neumann M, Cairns NJ, et al. Pathological TDP-43 distinguishes sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with SOD1 mutations. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:427–434. doi: 10.1002/ana.21147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai T, Hasegawa M, Akiyama H, Ikeda K, Nonaka T, Mori H, et al. TDP-43 is a component of ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:602–611. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai T, Mackenzie IR, Hasegawa M, Nonoka T, Niizato K, Tsuchiya K, et al. Phosphorylated TDP-43 in Alzheimer's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:125–136. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0480-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igaz LM, Kwong LK, Xu Y, Truax AC, Uryu K, Neumann M, et al. Enrichment of C-terminal fragments in TAR DNA-binding protein-43 cytoplasmic inclusions in brain but not in spinal cord of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:182–194. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amador-Ortiz C, Lin WL, Ahmed Z, Personett D, Davies P, Duara R, et al. TDP-43 immunoreactivity in hippocampal sclerosis and Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:435–445. doi: 10.1002/ana.21154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee AC, Gavett BE, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, Kowall NW, et al. TDP-43 proteinopathy and motor neuron disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:918–929. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181ee7d85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DB, Gitcho MA, Kraemer BC, Klein RL. Genetic strategies to study TDP-43 in rodents and to develop preclinical therapeutics for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;34:1179–1188. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winton MJ, Igaz LM, Wong MM, Kwong LK, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Disturbance of nuclear and cytoplasmic TAR DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) induces disease-like redistribution, sequestration, and aggregate formation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13302–13309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800342200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YJ, Xu YF, Cook C, Gendron TF, Roettges P, Link CD, et al. Aberrant cleavage of TDP-43 enhances aggregation and cellular toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7607–7612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900688106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmada SJ, Skibinski G, Korb E, Rao EJ, Wu JY, Finkbeiner S. Cytoplasmic mislocalization of TDP-43 is toxic to neurons and enhanced by a mutation associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:639–649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4988-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igaz LM, Kwong LK, Lee EB, Chen-Plotkin A, Swanson E, Unger T, et al. Dysregulation of the ALS-associated gene TDP-43 leads to neuronal death and degeneration in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:726–738. doi: 10.1172/JCI44867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel L, Frébourg T, Campion D, Lecourtois M. Both cytoplasmic and nuclear accumulations of the protein are neurotoxic in Drosophila models of TDP-43 proteinopathies. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;41:398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DB, Dayton RD, Henning PP, Cain CD, Zhao LR, Schrott LM, et al. Expansive gene transfer to the rat CNS and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis relevant sequelae when TDP-43 is overexpressed. Mol Ther. 2010;18:2062–2074. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegorzewska I, Bell S, Cairns NJ, Miller TM, Baloh RH. TDP-43 mutant transgenic mice develop features of ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18809–18814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908767106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns NJ, Neumann M, Bigio EH, Holm IE, Troost D, Hatanpaa KJ, et al. TDP-43 in familial and sporadic frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin inclusions. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:227–240. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba RA, Udan M, Bell S, Wegorzewska I, Shao J, Diamond MI, et al. Interaction with polyglutamine aggregates reveals a Q/N-rich domain in TDP-43. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26304–26314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.125039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budini M, Buratti E, Stuani C, Guarnaccia C, Romano V, De Conti L, et al. Cellular model of TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) aggregation based on its C-terminal Gln/Asn-rich region. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:7512–7525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.288720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udan M, Baloh RH. Implications of the prion-related Q/N domains in TDP-43 and FUS. Prion. 2011;5:1–5. doi: 10.4161/pri.5.1.14265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igaz LM, Kwong LK, Chen-Plotkin A, Winton MJ, Unger TL, Xu Y, et al. Expression of TDP-43 C-terminal fragments in vitro recapitulates pathological features of TDP-43 proteinopathies. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8516–8524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809462200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka T, Kametani F, Arai T, Akiyama H, Hasegawa M. Truncation and pathogenic mutations facilitate the formation of intracellular aggregates of TDP-43. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3353–3364. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccamo A, Majumder S, Deng JJ, Bai Y, Thornton FB, Oddo S. Rapamycin rescues TDP-43 mislocalization and the associated low molecular mass neurofilament instability. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27416–27424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.031278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai T, Hasegawa M, Nonoka T, Kametani F, Yamashita M, Hosokawa M, et al. Phosphorylated and cleaved TDP-43 in ALS, FTLD and other neurodegenerative disorders and in cellular models of TDP-43 proteinopathy. Neuropathology. 2010;30:170–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2009.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust KD, Nurre E, Montgomery CL, Hernandez A, Chan CM, Kaspar BK. Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton RD, Wang DB, Klein RL. The advent of AAV9 expands applications for brain and spinal cord gene delivery. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12:757–766. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.681463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RL, Hamby ME, Gong Y, Hirko AC, Wang S, Hughes JA, et al. Dose and promoter effects of adeno-associated viral vector for green fluorescent protein expression in the rat brain. Exp Neurol. 2002;176:66–74. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheean G. The pathophysiology of spasticity. Eur J Neurol. 2002;9 suppl. 1:3–9; dicussion 53. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.0090s1003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YJ, Gendron TF, Xu YF, Ko LW, Yen SH, Petrucelli L. Phosphorylation regulates proteasomal-mediated degradation and solubility of TAR DNA binding protein-43 C-terminal fragments. Mol Neurodegener. 2010;5:33. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecto F, Siddique T. UBQLN2/P62 cellular recycling pathways in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Muscle Nerve. 2012;45:157–162. doi: 10.1002/mus.23278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccamo A, Majumder S, Oddo S. Cognitive decline typical of frontotemporal lobar degeneration in transgenic mice expressing the 25-kDa C-terminal fragment of TDP-43. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms MM, Miller TM, Baloh RH.2009TARDBP-related amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP.eds). GeneReviews™ [Internet] University of Washington: Seattle, WA; 1993–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wils H, Kleinberger G, Janssens J, Pereson S, Joris G, Cuijt I, et al. TDP-43 transgenic mice develop spastic paralysis and neuronal inclusions characteristic of ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3858–3863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912417107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatom JB, Wang DB, Dayton RD, Skalli O, Hutton ML, Dickson DW, et al. Mimicking aspects of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Lou Gehrig's disease in rats via TDP-43 overexpression. Mol Ther. 2009;17:607–613. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberman RP, McCown TJ, Samulski RJ. Inducible long-term gene expression in brain with adeno-associated virus gene transfer. Gene Ther. 1998;5:1604–1611. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida A, Sasaguri H, Kimura N, Tajiri M, Ohkubo T, Ono F, et al. Non-human primate model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with cytoplasmic mislocalization of TDP-43. Brain. 2012;135 Pt 3:833–846. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty DM, Monahan PE, Samulski RJ. Self-complementary recombinant adeno-associated virus (scAAV) vectors promote efficient transduction independently of DNA synthesis. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1248–1254. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal J, Ström AL, Kilty R, Zhang F, Zhu H. p62 accumulates and enhances aggregate formation in model systems of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11068–11077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Vandenberghe LH, Alvira MR, Lu Y, Calcedo R, Zhou X, et al. Clades of adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J Virol. 2004;78:6381–6388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6381-6388.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton RD, Wang DB, Cain CD, Schrott LM, Ramirez JJ, King MA, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration related proteins induce only subtle memory-related deficits when bilaterally overexpressed in the hippocampus. Exp Neurol. 2012;224:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.