Abstract

Understanding and identifying new ways of mounting an effective CD8+ T cell immune response is important for eliminating infectious pathogens. Although upregulated programmed death-1 (PD1) in chronic infections (such as HIV-1 and tuberculosis) impedes T cell responses, blocking this PD1/PD-L pathway could functionally rescue the “exhausted” T cells. However, there exists a number of PD1 spliced variants with unknown biological function. Here, we identified a new isoform of human PD1 (Δ42PD1) that contains a 42-nucleotide in-frame deletion located at exon 2 domain found expressed in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Δ42PD1 appears to function distinctly from PD1, as it does not engage PD-L1/PD-L2 but its recombinant form could induce proinflammatory cytokines. We utilized Δ42PD1 as an intramolecular adjuvant to develop a fusion DNA vaccine with HIV-1 Gag p24 antigen to immunize mice, which elicited a significantly enhanced level of anti-p24 IgG1/IgG2a antibody titers, and important p24-specific and tetramer+CD8+ T cells responses that lasted for ≥7.5 months. Furthermore, p24-specific CD8+ T cells remain functionally improved in proliferative and cytolytic capacities. Importantly, the enhanced antigen-specific immunity protected mice against pathogenic viral challenge and tumor growth. Thus, this newly identified PD1 variant (Δ42PD1) amplifies the generation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cell immunity when used in a DNA vaccine.

Introduction

Programmed death-1 (PD1, CD279) is a member of the CD28 superfamily that negatively regulates the function of T cells through interaction with its two native ligands PD-L1 (CD274) and PD-L2 (CD273).1,2 PD1 is constitutively expressed at low levels on resting T cells and is upregulated on T cells, natural killer T (NKT) cells, B cells, and macrophages upon activation.3,4 However, the absence of PD1 in mice provided significant resistance against bacterial infection through innate immunity,5 further demonstrating the importance of the regulatory role of PD1 against pathogenic infections. In addition, PD1 plays significant roles in a number of autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis.6,7 In recent years, the PD1/PD-L pathway has been characterized extensively, particularly in chronic infections (Mycobacterium tuberculosis, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, HIV-1, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus) where the high expression of PD1 on pathogen-specific CD8+ T cells results in these cells being functionally “exhausted”, leading to the failure of clearing persistent infections.8 Furthermore, blockade of the PD1/PD-L1 pathway in vitro and in vivo with antibody or the soluble form (i.e., only containing extracellular domain) of PD1 is able to rescue the function of these exhausted HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells by restoring cytokine production, cell proliferation, and cytolysis.9,10

To date, four PD1 isoforms have been reported from alternatively spliced PD1 mRNA.11 Apart from one of these variants encoding a soluble form of PD1,12 the other three spliced variants have yet any function attributed to them. However, their highly induced expression following stimulation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) likely suggests an immunoregulatory function, which has been shown for variants of the other CD28 family molecules, such as CTLA-4 and CD28. One isoform of CTLA-4 (1/4CTLA-4) could exacerbate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis diseases in mice, with significantly increased level of CD4+ T cell proliferation and cytokine production compared with wild-type CTLA-4.13 Interestingly, overexpression of this variant resulted in the downregulation of wild-type CTLA-4 on CD4+ T cells. For CD28, four spliced variants were identified from human T cells with differential expression.14,15 The CD28i isoform was found expressed on the cell surface where it could associate with CD28 to enhance the costimulation capacity via CD28,15 further illustrating that apart from the conventional identified forms, spliced variants of the CD28 receptor family members could also encode immunoregulatory functions.

In this study, we identified and characterized from human healthy PBMC donors a new isoform of PD1 that lacks 42-nucleotide region from exon 2, which we named Δ42PD1. This isoform is distinct from PD1 that it does not bind to PD-L1 or PD-L2 or is not recognized by PD1-specific monoclonal antibodies. Like PD1, Δ42PD1 mRNA was found expressed in various immune-related cells. Using both soluble and membrane-bound forms of recombinant Δ42PD1, we found that Δ42PD1 could induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines from human PBMCs and murine dendritic cells (DCs). Furthermore, when used in conjunction to DNA immunization in mice against HIV-1 Gag p24 antigen as a fusion vaccine, a markedly increased level of antigen-specific B and T cell immunity was observed in vivo, with enhanced functional CD8+ T cells and provided protection against viral challenge and inhibition of tumor growth in mice.

Results

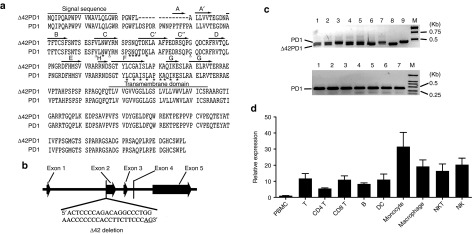

Discovery of a novel PD1 isoform

To investigate the polymorphism of PD1 gene, we examined mRNA transcripts from PBMCs of 25 human healthy donors. In one representative donor with seven clones, reverse transcription-PCR and sequence analysis showed that six clones harbored an identical variant of PD1, which consists of a 42-base pairs deletion from the start of exon 2 that is equivalent to a 14 amino acid in-frame deletion (DSPDRPWNPPTFFP) (Figure 1a,b). Hence, we named this PD1 variant as Δ42PD1. To verify that this deletion is not due to intrinsic genomic defect from multiple donors, we performed PCR using primers that flank the deleted region. As a control, genomic DNA only detected wild-type PD1 (Figure 1c, lanes 1–7, lower gel), whereas both wild-type PD1 and Δ42PD1 transcripts were readily detected from cDNA generated from five out of seven donor PBMCs (Figure 1c, lanes 1–7, upper gel), which were confirmed by sequence analysis. Hence, this transcript variant is likely due to alternative splicing, and not mutation on the chromosomal level. Alternative splicing of pre-mRNA is usually found in mammalian cells under two conditions: mutation of the junction site between introns and exons, or alternative selection of splicing sites.16 For the latter, an AG dinucleotide splicing donor is often required,17 and indeed, there exists an alternative AG splicing donor at the 3′ terminus of the deletion region of exon 2 that probably leads to the formation of the Δ42PD1 mRNA (Figure 1b). In total, 24 out of 25 donors harbored the Δ42PD1 variant. Next, we wanted to determine the expression profile of Δ42PD1 among immune cells found in PBMCs. Since a monoclonal antibody directed against Δ42PD1 is unavailable, we performed quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR using specific primers to measure the mRNA expression of Δ42PD1 in different cell types. For this purpose, cell subpopulations were sorted from PBMCs from five independent healthy donors according to various cell markers: NK cells (CD3−CD56+), T cells (CD3+), CD3+CD4+ T and CD3+CD8+ T cells, B cells (CD3−CD19+), NKT cells (CD3+CD56+), monocytes (CD3−CD11c−CD14+), macrophages (CD3−CD11c−CD68+), and DCs (CD3−CD11c+). As shown in Figure 1d, the relative expression of Δ42PD1 was found highest among monocytes, macrophages, NK and NKT cells, and to a lesser extent on B cells, T cells (CD4 or CD8), and DCs.

Figure 1.

Identification of a novel PD1 isoform. (a) Amino acid sequence alignment of Δ42PD1 and PD1 (GenBank accession no.: NM_005018) identified from a representative healthy human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) donor. Dashed line represents the 14-amino acid deletion found in Δ42PD1. Signal sequence and the transmembrane region are indicated. IgV domain including the front A′GFCC′C′′ β-sheet and the back ABED sheet are highlighted by the arrows. Asterisks show the putative amino acids for ligand interaction. (b) Schematic genomic structure of PD1 with the highlighted location of the exact 42-nucleotide deletion in exon 2. (c) Δ42PD1 and PD1 PCR products were amplified from cDNA clones (upper gel) or PD1 alone from the genomic DNA (lower gel) generated from healthy human PBMCs. Lanes 1–7 in both the gels represent PCR results from seven human donors. Lanes 8 and 9 are Δ42PD1 and PD1-positive controls, respectively. Lane M represents DNA molecular weight marker. (d) Relative mRNA expression of Δ42PD1 from subpopulations of PBMCs sorted from five independent healthy blood donors, normalized to housekeeping gene gapdh and total PBMC samples. B, B cell; DC, dendritic cell; NK, natural killer cell; NKT, natural killer T cell; T, T cell.

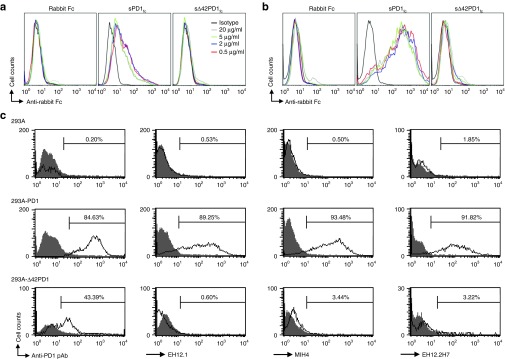

Δ42PD1 is distinct from PD1 and does not interact with PD-L1/L2

To gain a better understanding of the possible function of Δ42PD1, we generated DNA plasmid vectors to express soluble forms of PD1 or Δ42PD1 protein tagged to rabbit Fc, denoted as sPD1fc and sΔ42PD1fc, respectively, that encodes only the extracellular regions and the former has been used to characterize the function of PD1 previously.12 In addition, to account for tertiary structural disruptions with the deleted 14 amino acids, we substituted back 14 alanines to generate s14APD1fc. Purified proteins of sPD1fc, sΔ42PD1fc, and s14APD1fc were generated by transient transfection of 293T cells with subsequent purification from culture supernatants. The purity of these proteins was checked by coomassie blue-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Supplementary Figure S1). First, to determine whether these proteins could bind to PD1 ligands, they were used to treat 293T cells transiently transfected with human PD-L1 or PD-L2 at different concentrations, and signals from binding were detected by anti-rabbit Fc antibody using flow cytometry (Figure 2a,b). As expected, sPD1fc was bound to both PD-L1 and PD-L2, but not sΔ42PD1fc or s14APD1fc (data not shown). These findings illustrate that the protein encoded by the Δ42PD1 isoform is unlikely to interact with PD1 ligands and the 14 alanines were insufficient to restore the binding. Second, to further demonstrate that Δ42PD1 and PD1 are distinct molecules, we expressed their full-length membrane-bound form by stable transfection of 293A cell line (293A-PD1 and 293A-Δ42PD1) and used commercial antibodies for detection by flow cytometry. PD1-specific monoclonal antibodies (clones EH12.1, MIH4, and EH12.2H7) detected PD1 but were unable to detect Δ42PD1 (Figure 2c). As these commercial antibodies bind to the PD1/PD-L interacting moieties, these results further reinforce that Δ42PD1 differs from PD1 structurally at the PD-L–binding interface. However, commercial polyclonal anti-PD1 antibody could detect both PD1 and Δ42PD1 (Figure 2c), suggesting that Δ42PD1 could still be recognized, likely through a region conserved between PD1 and the Δ42PD1 isoform outside the PD-L–binding interface. These results indicate that the conformation of this Δ42PD1 isoform differs from PD1 primarily at the domain of PD-L1/L2 interaction, and led us to further examine the possible structure of Δ42PD1 in silico. As the 14-amino acid deletion partially exists in the published PD1 crystal structure,18 we remodeled human PD1 and included the initial 14-amino acids in the structure in the β-strand A of human PD1 (Supplementary Figure S2; highlighted red). Based on the model, the deletion of the N-terminal β-strand A that extensively interacts with the core structure, may result in a conformation that is distinct from the correct folding of wild-type PD1, and thus renders Δ42PD1 unable to bind to PD-L1/L2.

Figure 2.

Characterization of the function of Δ42PD1 isoform. 293T cells transiently transfected to express human (a) PD-L1 or (b) PD-L2, and treated with purified recombinant proteins at series of concentrations–0.5, 2, 5, and 20 μg/ml to investigate binding affinity. Results were analyzed by flow cytometry using a detection antibody against rabbit Fc (shaded) or isotype control (solid line). (c) Plasmids encoding PD1 or Δ42PD1 were stably transfected or untransfected 293A cells, and the detection was determined by flow cytometry with a polyclonal anti-PD1 antibody or three monoclonal anti-PD1 antibodies with clone names indicated on the x-axes. Percentage of cells with positive staining (solid line) is shown with corresponding antibodies and isotype control (shaded). Data is representative of three independent experiments. pAb, polyclonal antibody.

Δ42PD1 induces the production of proinflammatory cytokines in human PBMCs

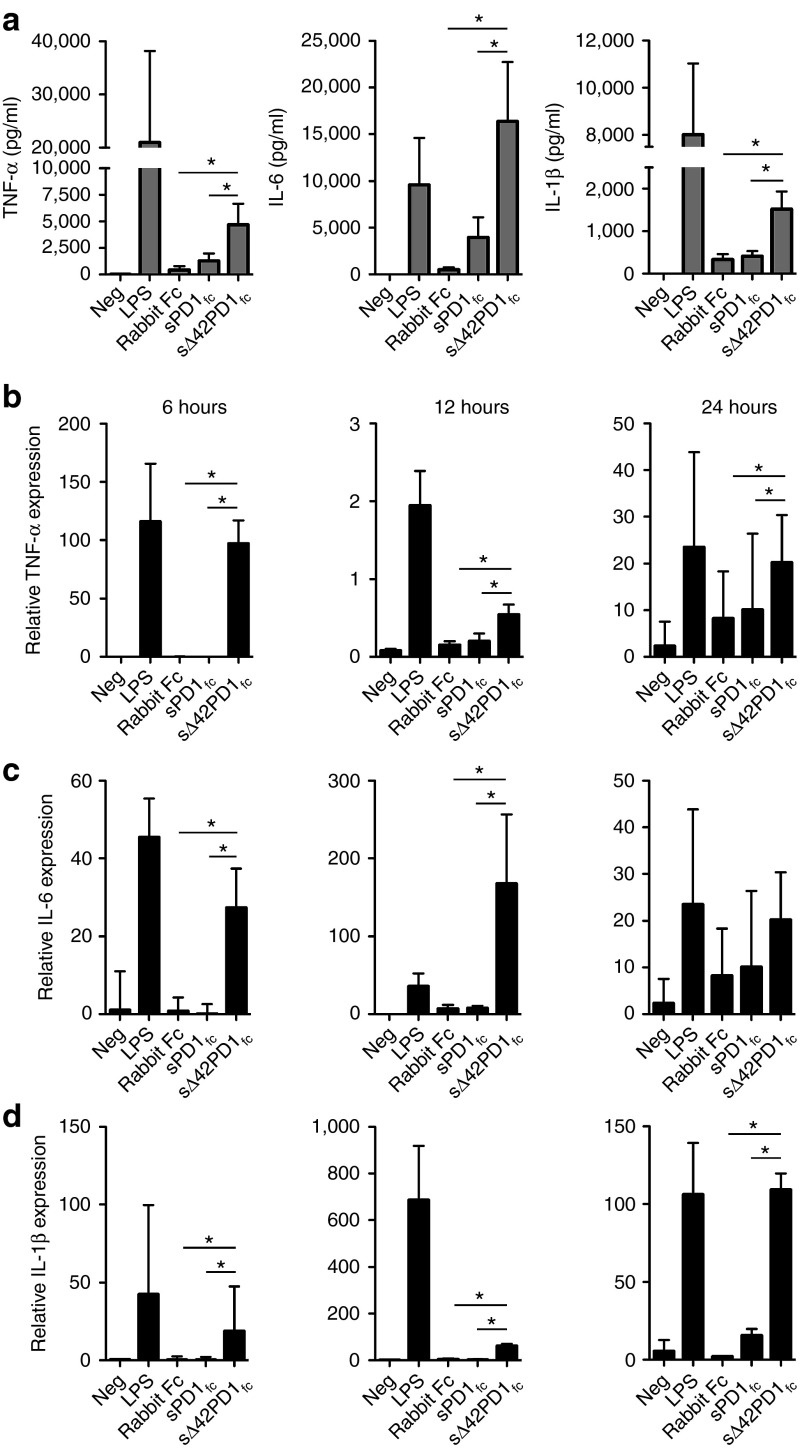

We next searched for the function of Δ42PD1 using the purified sΔ42PD1fc proteins to treat human PBMCs and measured the production of cytokines. PBMCs were treated with purified sPD1fc, sΔ42PD1fc or rabbit Fc recombinant proteins for 24 hours, and supernatants were collected to determine the cytokine release profile by a multiplex assay. Untreated cells or lipopolysaccharide served as negative and positive controls, respectively. As shown in Figure 3a, PBMCs treated with sΔ42PD1fc had significantly higher levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-1β cytokine production compared with sPD1fc or rabbit Fc. Other cytokines interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, and TNF-β were not detected following treatment by these recombinant proteins (data not shown). For verification, quantitative real-time PCR was performed at 6, 12, and 24 hours post-treatment of PBMCs, and relative mRNA expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β was also found significantly increased with sΔ42PD1fc protein treatment compared with sPD1fc that remained at levels similar to rabbit Fc (Figure 3b–d). In addition, to confirm that not only the soluble form can induce such effects, we also examined cytokine induction using γ-irradiated 293A cells stably expressing surface PD1 or Δ42PD1 and cocultured with PBMCs, and the same trend as with using the soluble form of proteins at least for the 6-hour timepoint after treatment was observed (Supplementary Figure S3). Collectively, these data indicate that both soluble and membrane-bound Δ42PD1 could induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines.

Figure 3.

Functional analysis of human sΔ42PD1 in vitro. (a) Cytokine release profile of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) culture supernatants treated with purified proteins of rabbit Fc, sPD1fc or sΔ42PD1fc for 24 hours. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR analysis of human PBMCs after protein treatment for 6, 12, and 24 hours, for (b) tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), (c) interleukin-6 (IL-6), and (d) IL-1β mRNA expression normalized to gapdh. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) served as positive control. Data represents mean ± SEM of five independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

Δ42PD1 fused to antigen promotes specific adaptive immunity in vivo

As TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β have cooperative and key roles in the generation of adaptive immunity,19 we next sought to determine whether Δ42PD1 can perform this function in vivo. For this purpose, we generated a fusion DNA vaccine construct comprised of HIV-1 Gag p24 as the target immunogen with human sΔ42PD1 tagged to rabbit Fc (sΔ42PD1-p24fc; Supplementary Figure S4a); with DNA encoding for p24fc as control. The rabbit Fc used contains only the CH2-CH3 domain and thus does not bind to rabbit Fcγ receptor. The tPA-leader was fused with the leader sequence of PD1 to increase protein release, whereas the signal peptide cleavage of Δ42PD1 remains the same as wild-type PD1. Expression of their encoded protein was confirmed by western blotting (Supplementary Figure S4b). Subsequently, we delivered these DNA (20 μg/shot) to Balb/c mice intramuscularly with electroporation (EP)20 according to our previously used immunization regimen (Supplementary Figure S4c). As shown in Supplementary Figure S4d, antibody responses detected in mice sera by ELISA for both IgG2a (Th1; 1.5-fold) and IgG1 (Th2; sevenfold) raised against p24 were significantly higher (P < 0.05) in mice immunized with sΔ42PD1-p24fc than p24fc. For T cell responses, IFN-γ–producing cells were measured using ELISPOT assay against Gag peptides specific for CD4+ (gag26) and CD8+ (gagAI) T cells. Almost tenfold greater number of IFN-γ+ elispots for gagAI-specific CD8+ T cells were detected in splenocytes of sΔ42PD1-p24fc–immunized mice compared with p24fc-immunized group (P < 0.001) or placebo (phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)). However, gag26-specific CD4+ elispots remained low and there were no differences between the two immunized groups or placebo (Supplementary Figure S4e). Clearly, immunization with human sΔ42PD1 fused to p24fc elicited a substantial level of CD8+ T cell response and modest antibody responses against p24, suggesting a functional role of human sΔ42PD1 in DNA vaccination in mice. Considering that human sΔ42PD1 might be immunogenic in mice due to sequence diversity, we examined whether immune recognition and response have been directed against human sΔ42PD1. Indeed, mouse serum from sΔ42PD1-p24fc–immunized mice recognized Δ42PD1-GST purified protein by western blotting (Supplementary Figure S4f), suggesting that anti-human Δ42PD1 immunity may have interfered with the generation of anti-p24 immune response.

Murine sΔ42PD1 fusion DNA vaccine elicited an enhanced level of antigen-specific CD8+ T cell immunity in mice

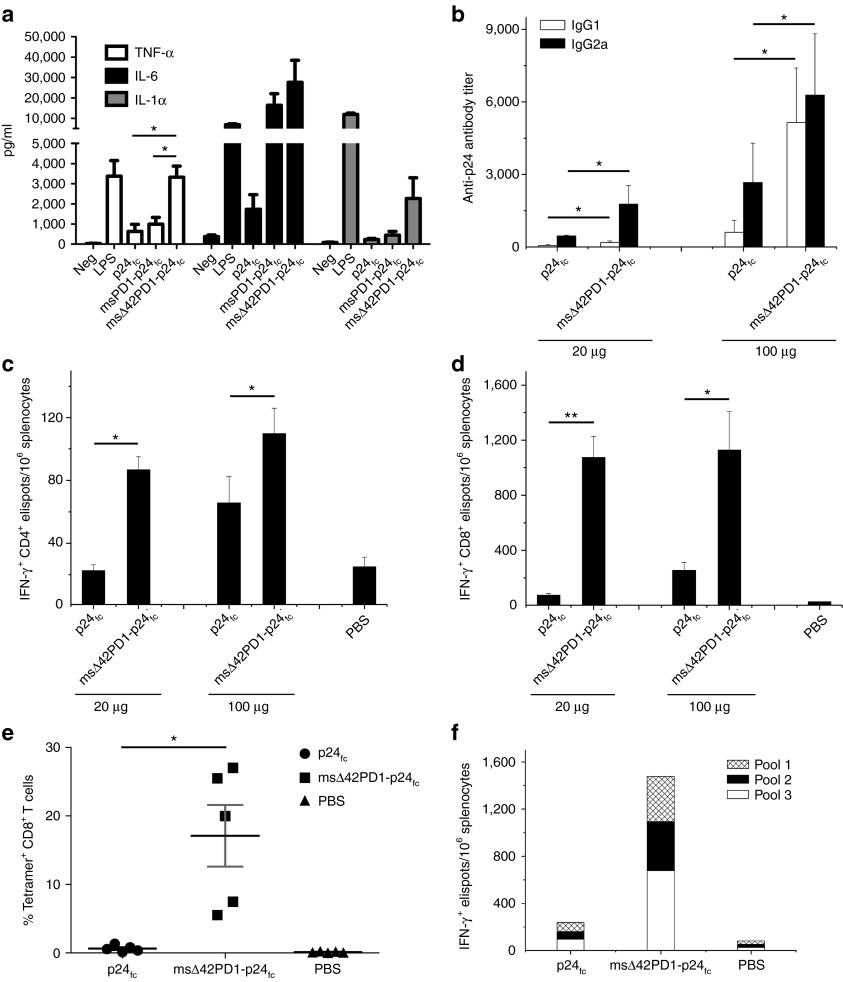

We consequently generated the murine version of fusion DNA constructs by substituting human sΔ42PD1 with murine (m)sΔ42PD1 with deletions at the same nucleotide positions to generate msΔ42PD1-p24fc. Although the native Δ42PD1 isoform was not detected in splenocytes of Balb/c or C57BL6/N mice by reverse transcription-PCR and sequencing (data not shown), we aimed to use the equivalent (m)sΔ42PD1 isoform to study the efficacy of our DNA fusion vaccine strategy in mice. To verify the function of murine counterparts, we first generated recombinant msΔ42PD1-p24fc proteins and tested for binding to PD-L1/L2 expressed on transiently transfected 293T cells (Supplementary Figure S5). Expectedly, msΔ42PD1-p24fc or p24fc did not bind to either human or murine PD1 ligands. We also tested whether the recombinant msΔ42PD1-p24fc protein could induce proinflammatory cytokines. Splenocytes from Balb/c mice were treated with purified proteins msΔ42PD1-p24fc or p24fc, and an increased level (approximately twofold) of mRNA expression of TNF-α from 12 and 24 hours post-treatment was significantly induced by msΔ42PD1-p24fc protein compared with p24fc (P < 0.05; Supplementary Figure S6a). Although for IL-6 and IL-1α, a modest but statistically significant elevated level of gene expression was detected at 6 hours (~1.3-fold; P < 0.05) and 24 hours (~1.6-fold; P < 0.05) (Supplementary Figure S6b,c). However, the release of these cytokines 24 hours post-treatment did not reach any significant differences compared with control (data not shown). Given the heterogeneity of splenocytes, we isolated and cultured bone marrow-derived DCs to perform the same experiment, and as shown in Figure 4a, higher level of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α (approximately threefold), IL-6 (~1.5-fold), and IL-1α (approximately fivefold) were produced by msΔ42PD1-p24fc–treated bone marrow-derived DCs compared with p24fc. Therefore, consistent to human sΔ42PD1fc, msΔ42PD1-p24fc can also stimulate the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and that the p24 antigen was not a contributing factor for this induction.

Figure 4.

Enhanced antigen-specific immunogenicity of msΔ42PD1-p24fc DNA/electroporation in mice. (a) Purified CD11c+ bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BM-DCs) from Balb/c mice were treated by purified protein msΔ42PD1-p24fc, p24fc or positive control lipopolysaccharide for 24 hours. Supernatants were collected to analyze cytokine releasing of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-1α. Data represents mean ± SEM of six independent experiments. *P < 0.05. Balb/c mice were vaccinated using fusion DNA plasmids (20 or 100 μg dose), and p24-specific immune responses generated were measured by (b) ELISA for antibody responses, (c) ELISPOT assay for CD4-specific epitope gag26, (d) CD8-specific epitope gagAI IFN-γ+ responses, and (e) H-2Kd p24 tetramer staining for specific CD8+ T cell response from splenocytes displayed as scatter plot (n = 5). (f) ELISPOT assay was performed on splenocytes using three non-overlapping p24 peptide pools. Data represents means ± SEM of at least two independent experiments of three mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. IFN, interferon; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Next, we performed in vivo vaccination experiments to determine whether a higher level of antigen-specific immunity could be achieved compared with the human sΔ42PD1 counterpart using the same immunization regimen (Supplementary Figure S4c), but with two different doses (20 and 100 μg DNA/shot). Antibody responses show significantly higher level of IgG1 (Th2) and IgG2a (Th1) in sera of mice vaccinated with 20 μg of msΔ42PD1-p24fc compared with p24fc (three- and fourfold, respectively; P < 0.05; Figure 4b), which was further amplified at the 100 μg dose. Unlike human sΔ42PD1-p24fc, no immune response was raised against the msΔ42PD1 portion of the fusion molecule msΔ42PD1-p24fc, as immunized mouse serum did not detect msΔ42PD1 protein by western blotting (Supplementary Figure S7). Meanwhile, IFN-γ ELISPOT assay detected a significantly increased level of p24-specific CD4+ T cell responses (~100 elispots/106 splenocytes; ~3.5-fold) and CD8+ (~1,000 elispots/106 splenocytes; ~15-fold) from mice vaccinated with 20 μg dose msΔ42PD1-p24fc compared with p24fc or placebo (Figure 4c,d). However, no significant improvement was found in mice vaccinated at 100 μg dosage, which suggests that a low dose of msΔ42PD1-p24fc was sufficient to achieve this level of IFN-γ+ T cell response. When we examined the antigen specificity of CD8+ T cells from mice vaccinated (20 μg dose) with msΔ42PD1-p24fc, we found a greater frequency of p24-specific tetramer+CD8+ T cells at an average of 17% compared with those in p24fc group (>11-fold; P < 0.05; Figure 4e). In addition, epitopic breadth was enhanced in splenocytes detected using three non-overlapping p24 peptide pools (Figure 4f).

Long-term memory CD8+ T cells immune responses is sustained in msΔ42PD1-p24fc–immunized mice

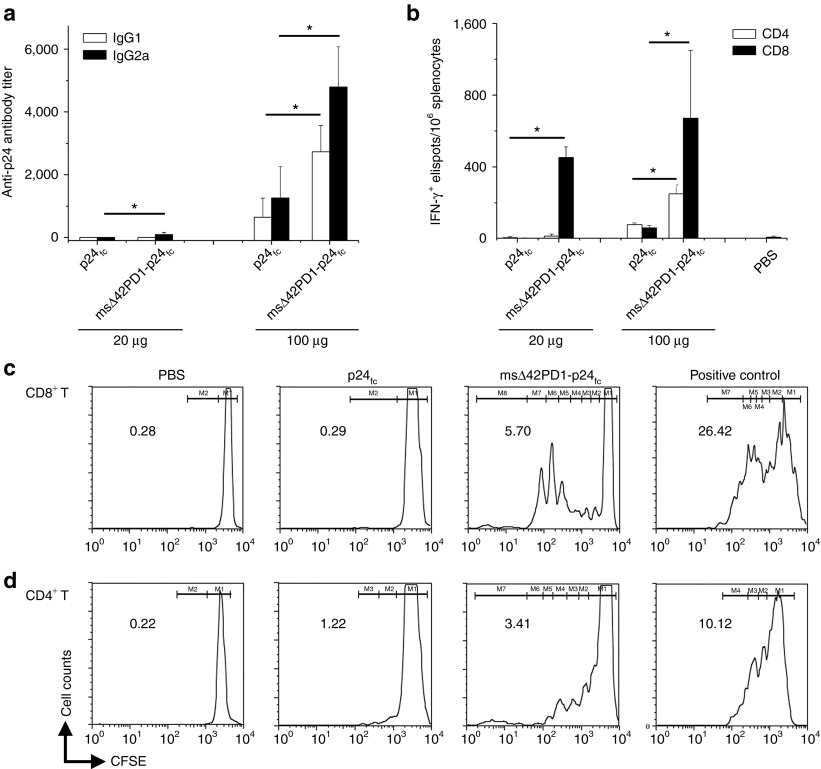

To determine whether long-term memory responses can be achieved with msΔ42PD1-p24fc, we further analyzed p24-specific cell-mediated immunity 30 weeks (7.5 months) post-vaccination. Anti-p24 antibody titers were retained at 100 μg groups, with IgG1 and IgG2a responses being higher for msΔ42PD1-p24fc compared with p24fc; however, at 20 μg dose, antibody responses of both groups remained relatively low (Figure 5a). Although memory CD4+ IFN-γ+ elispots was not apparent unless a higher dose of 100 μg DNA vaccine was used (approximately twofold; P < 0.05; Figure 5b), CD8+ T cell immunity appears to be long-lived, as a significant level of CD8+ IFN-γ+ elispots could still be detected 30 weeks after msΔ42PD1-p24fc DNA vaccination in two doses (Figure 5b). Furthermore, we evaluated proliferative memory T cells by carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) assay for both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in splenocytes isolated from 30 weeks post-vaccinated mice. The data showed that both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from msΔ42PD1-p24fc–vaccinated mice (at 100 μg dose) were proliferative upon stimulation, being ~2.8-fold and 20-fold greater than p24fc control group, respectively (Figure 5c,d). Overall, the use of msΔ42PD1 as an intramolecular adjuvant in the DNA vaccine vastly improved the elucidation of the levels of antigen-specific long-lived B and T cell immunity, especially CD8+ T cell immune responses compared with antigen alone.

Figure 5.

Long-term memory responses induced by msΔ42PD1-p24fc vaccination. Thirty weeks after immunization, mice were sacrificed to assess long-lived memory response for (a) anti-p24 antibody and (b) CD4 and CD8 IFN-γ+ elispots. Data represents means ± SEM of two independent experiments of three mice per group. *P < 0.05. CFSE proliferation assay was performed on (c) CD8+ T and (d) CD4+ T cells from splenocytes of 30 weeks post-vaccinated mice for 5 days of stimulation with bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BM-DCs) (ratio, 1 DC:10 T) and p24 peptide pool plus anti-CD28. Anti-CD3/anti-CD28 stimulation served as positive control. Numbers represent percentage of dividing cells calculated using each division gate (M). CFSE, carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester; IFN, interferon; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; T, T cell.

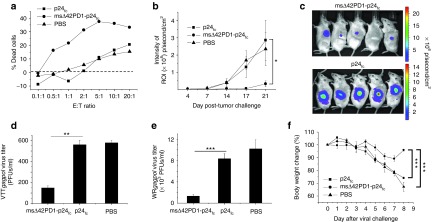

The efficacy of msΔ42PD1-p24fc DNA vaccine in mice

To further assess the efficacy of our fusion DNA vaccine, we next sought to determine whether these CD8+ T cells are cytolytic and provide protection. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) assay was performed using a modified mesothelioma cell line (AB1)21 to express HIV-1 Gag with luciferase as target cells (AB1-HIV-1-Gag) that we constructed. Splenocytes isolated from vaccinated mice (2 weeks post-vaccination) were cocultured at various ratios with AB1-HIV-1-Gag target cells and measured the frequency of dead target cells. Compared with p24fc or placebo groups, splenocytes isolated from msΔ42PD1-p24fc–immunized mice were able to kill efficiently even at a ratio of one effector T cell to two target cells (Figure 6a). To evaluate whether msΔ42PD1-p24fc protects vaccinated mice from tumor challenge, we immunized mice with 100 μg msΔ42PD1-p24fc and p24fc intramuscularly with EP according to our regimen (Supplementary Figure S4c). Three weeks after the last boost, mice were challenged subcutaneously using 5 × 105 AB1-HIV-1-Gag tumor cells, and in vivo imaging was performed twice a week up to 3 weeks. Results in Figure 6b,c showed that the tumor growth in msΔ42PD1-p24fc–vaccinated mice was inhibited up to 17 days compared with p24fc and PBS control, illustrating that msΔ42PD1-p24fc vaccination conferred protective immunity against tumor growth systematically.

Figure 6.

Efficacy of msΔ42PD1-p24fc vaccination in mice. (a) Effector splenocytes (2 weeks post-vaccination) were used for cytotoxicity assay against p24-expressing target AB1-HIV-1-Gag cells at various ratios. Percentage of dead cells was calculated and the dashed line showed the background signal of target cells alone. (b) Immunized mice were challenged subcutaneously by 5 × 105 AB1-HIV-1-Gag cells 3 weeks post-vaccination, (c) tumor image were taken twice a week to detect luciferase intensity and representative images at day 17 post-challenge is shown. Protection of immunized mice against intranasal virus challenge 3 weeks after the final immunization with (d) VTTgagpol and (e) virulent WRgagpol. Virus titer was measured from lung homogenates from mice sacrificed 8 days post-challenge on Vero cell plaque formation. (f) Body weight was measured daily over time and calculated as percentages compared with day 0 of WRgagpol challenge. Functional assay results show the representative data from two independent experiments. Protection studies were performed from at least five mice in each group and data represent the means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. E:T ratio, effector:target ratio; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PFU, plaque-forming unit; ROI, region of interest.

Furthermore, we assessed protection of vaccinated mice against virus infection. Here, msΔ42PD1-p24fc–, p24fc-, and PBS-vaccinated mice were challenged (at 3 weeks post-vaccination) by either vaccinia virus strain TianTan (VTTgagpol) (for 20 μg dose vaccinated mice) or virulent strain Western Reserve (WRgagpol) (for 100 μg dose vaccinated mice) that we constructed. Significantly less virus titer was found in lung homogenates of msΔ42PD1-p24fc group compared with p24fc or placebo groups (Figure 6d,e), and significantly reduced body weight loss (Figure 6f). Taken together, these data further illustrates the immunogenic advantage of msΔ42PD1-p24fc in eliciting p24-specific protective immunity.

Discussion

In this study, we report a new technique to potentiate antigen-specific antibody and particularly CD8+ T cell immune responses, based on our discovery of an alternatively spliced isoform of PD1, Δ42PD1 (Figure 1). As the Δ42 deletion results in the loss of the β-strand A of human PD1 (Supplementary Figure S2) renders this molecule unable to bind PD-L1/L2 or specific PD1-blocking monoclonal antibodies (Figure 2). Δ42PD1-mediated enhancement of antigen-specific immunity is unlikely through PD-L1/L2 interaction with DCs but rather through a distinct mechanism. Our finding of stimulating proinflammatory cytokines by Δ42PD1 may at least partially contribute to the overall T cell immunity enhanced by our Δ42PD1-based fusion DNA vaccine. In particular, since the enhanced antigen-specific CD8+ T cell immunity confers functional and long-lasting effects in vivo, our findings suggest that Δ42PD1-based fusion DNA vaccine offers new opportunities to improve vaccine and immunotherapy efficacy against pathogens and cancers.

Δ42PD1 is a newly discovered PD1 isoform, which may induce proinflammatory cytokines for function. This isoform was found among healthy Chinese blood donors whose PBMCs expresses a PD1 transcript with an identical 42-nucleotide deletion at the beginning of exon 2 (Figure 1), which differs from other alternatively spliced PD1 variants as reported previously.11 Interestingly, Δ42PD1 mRNA is preferentially expressed in monocytes, macrophages, NKT, and NK cells as compared with DCs, B cells, and T cells (Figure 1d). This phenomenon has not been reported for PD1 or spliced variants of other CD28 family members such as CTLA-4 and CD28.14,15,22 Whether this has any biological relevance is yet to be determined. Unlike in human, Δ42PD1 was not detected in mouse splenocytes. Our study, however, using the equivalent deletion region in murine PD1-replicated human Δ42PD1 data in vitro also induced higher expression of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1α). Given that soluble forms of PD1, CD28, CD80, CD86, and CTLA-4 can be found in sera of patients suffering from autoimmune diseases such as Sjogren's syndrome,7,23 systemic lupus erythematosus,24 multiple sclerosis,25 neuromyelitis optica,25 and rheumatoid arthritis,12 we have yet the required specific antibody to detect naturally occurring sΔ42PD1 in diseases or infections. Nonetheless, Δ42PD1 appears to be distinct from PD1: first, it does not bind to PD-L1/L2, and second, recombinant soluble or membrane-bound Δ42PD1 (but not PD1) can induce the expression of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β. Therefore, we believe that this PD1 variant has distinct immunoregulatory functions that could influence the stimulation of adaptive immune response. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of a function attributed to a PD1 spliced variant resulted from a partial exon deletion.

Eliciting high levels of adaptive CD8+ T cell immunity is one of the important determinants of an effective vaccine against intracellular pathogens and cancer.26 Thus, we utilized Δ42PD1 as an intramolecular adjuvant in our fusion DNA vaccine strategy, and elicited remarkably enhanced functional CD8+ T cell immunity against HIV-1 Gag p24 in vivo (Figure 4d,e). At a dose of 20 μg of DNA in Balb/c mice, msΔ42PD1-p24fc/EP vaccination could achieve robust p24-specific CD8+ (~1,000 elispots/106 splenocytes; ~20-fold greater than p24fc), which are markedly different from those using either three doses of 1 mg of gene-optimized ADVAX DNA vaccine or two doses of 106 TCID50 vaccinia-vectored ADMVA vaccine that only induced 200–250 spot-forming units/106 splenocytes against the identical GagAI epitope.27 Meantime, an average 17% of tetramer+CD8+ T cells from our DNA vaccination was similar to those elicited by rAd5-Gag vaccination with three dosages of 1010 virus particles, or by a DC-SIGN–targeted lentivirus-Gag with two doses of 5 × 106 transduction units.28,29 The immunogenicity of our novel fusion DNA/EP vaccine strategy, therefore, is potent for eliciting anti-HIV CD8+ T cell immunity. Furthermore, as long-lasting CD8+ T cell-mediated immunity to a particular intracellular pathogen requires the establishment of a memory cell pool that proliferates rapidly in response to antigen re-encounter, Δ42PD1 fusion DNA induced higher frequencies of not only IFN-γ producing but proliferating p24-specific CD8+ T cells 7.5 months after immunization (Figure 5b,d). Most importantly, msΔ42PD1-p24fc vaccination significantly inhibited tumor growth in vivo (Figure 6b,c) in line with more effective cytotoxic T cells capable of eliminating AB1-HIV-1-Gag tumor cells in vitro (Figure 6a). In addition, mice vaccinated with msΔ42PD1-p24fc were protected against both attenuated (VTTgagpol) and virulent (WRgagpol) vaccinia viruses from mucosal challenges (Figure 6d,e) with minimal body weight loss (Figure 6f). Here, since neither neutralizing antibodies nor T cell immunity against the backbone vaccinia viruses were generated, the observed protection was also primarily due to the significantly enhanced T cell immunity directed at HIV-1 Gag p24.

One possible mechanism of the success of msΔ42PD1 fusion DNA vaccine in mice may be contributed by the ability of msΔ42PD1 to induce the expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1α/β. These cytokines may play active roles in the generation of antigen-specific adaptive immunity by acting on antigen-presenting cells, such as DCs. TNF-α can induce the maturation of professional antigen-presenting DCs and increase the expression of major histocompatibility complex and costimulatory molecules,30,31 and migration to draining lymph nodes to prime naive T cells.30 With the addition of IL-1α/β, these matured DCs become more potent at promoting the differentiation of IFN-γ–producing T cells in a Th1 manner.32 While synergistically, TNF-α and IL-6 can provide costimulatory cytokine signals to induce the proliferation of T cells.33 IL-6 has also been found to inhibit the activity of regulatory T cells to ensure the production of IFN-γ by CD4+ T cells.34 As elevated levels of cytokines were not detected systemically in mice sera (Supplementary Table S3), we therefore, speculate that the high level of functional B and T cell immunity elicited by our sΔ42PD1-based DNA fusion vaccine may be contributed by the induction of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1α/β at the site of vaccination. Other DNA vaccine studies have also shown that T cell responses were elicited by coadministering plasmids encoding HIV-1 Env and CD86 adjuvant35,36 to enable non-bone marrow–derived cells to prime CD8+ T cells at the site of injection assisted by a proinflammatory environment that can enhance antigen presentation.37 Interestingly, wild-type sPD1 did not significantly induce TNF-α, IL-6 or IL-1α/β (Figures 3 and 4a), but vaccination in mice using a similar fusion construct (msPD1-p24fc) also elicited high level of CD8+ T cell immunity (Supplementary Figure S8b,c), suggesting that msPD1-p24fc might employ a different mechanism as compared with msΔ42PD1-p24fc. Indeed, while msPD1-p24fc is targeted to DCs mainly via PD-L1/L2 expressed on DCs,38 the receptor/ligand for sΔ42PD1 remains unknown. Since sΔ42PD1 binds to DCs weakly (Supplementary Figure S8a), it is necessary to identify this receptor/ligand in future studies because difference in antigen targeting via various DC surface proteins (such as DC-SIGN, CTLA-4, Clec9A, DEC-205) may shape distinct adaptive immune responses.39,40,41,42,43 As for the weak CD4+ but strong CD8+ T cell responses observed, other cytokine signals such as IL-1244 or type I IFN45 may play a role in favoring naive CD8+ T cell activation. It has also been reported that IL-15 alone can substitute for CD4+ T helper cell in stimulating CD8+ T cell activation and expansion.46 Our preliminary results showed that IFN-β, IL-12, and IL-15 transcripts were increased in PBMCs treated with sΔ42PD1fc after 12 hours (Supplementary Figure S9). In addition, the induction of IL-1α/β and IL-6 by sΔ42PD1fc may also contribute to CD8+ T cell response by inhibiting activation-induced cell death.47 We, however, cannot exclude other mechanisms in potentiating CD8+ T cells such as antigen cross-presentation engaged by antigen-presenting cells without the necessity of CD4+ T helper cells.46,48 The detailed underlying mechanism by which Δ42PD1 performs its function remains to be investigated relies on the identification of the ligand/receptor. Taken together, our data presents this novel PD1 isoform (Δ42PD1) as a potential intramolecular adjuvant for vaccine development to induce high level of functional and long-lived antigen-specific CD8+ T immunity not only against pathogens such as HIV-1 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis but also cancers.

Materials and Methods

All primer sequences and antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

Cell isolation and gene cloning. PBMCs were freshly isolated from buffy coats of anonymous healthy human blood donors using Ficoll-Hypaque (GE Healthcare, San Francisco, CA). Human full-length PD1, PD-L1, and PD-L2 genes were amplified from PBMCs with respective primer pairs: PD1 forward/PD1 reverse, PD-L1 forward/PD-L1 reverse, and PD-L2 forward/PD-L2 reverse.

PCR analysis of PD1 and Δ42PD1. Cellular genomic DNA was extracted from human PBMCs using the QIAamp DNA Blood Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). PD1 amplification from genomic DNA amplification used primer pair PD-1D forward/PD-1D reverse. Another primer pair (nPD-1 forward/nPD-1 reverse) flanks the deletion region to detect both PD1 and Δ42PD1 cDNA samples by PCR. All PCR products were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gel.

Quantitative real-time PCR of Δ42PD1 transcript expression. cDNA templates were generated using Superscript VILO Master Mix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) from total RNA extracted using RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio, Madison, WI), followed by real-time PCR reactions performed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara Bio) with specific primer pairs (listed in Supplementary Table S1) in the ViiA 7 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and analyzed with ViiA7 RUO software (Applied Biosystems) normalized to gapdh (for human) or β-actin (for murine) and untreated negative control.

DNA plasmids and fusion proteins. PD-L1 and PD-L2 genes were amplified from cDNA of human PBMC using primer pairs EL1 forward/EL1 reverse and EL2 forward/EL2 reverse, respectively. The extracellular domains (i.e., soluble forms) of PD1 and Δ42PD1 were amplified from the PD1 and Δ42PD1 genes using primer pair ED1 forward/ED1 reverse. The amplified ectodomains of PD1 and Δ42PD1, and PD-L1 and PD-L2 were inserted into the expression vector pVAX fused with the CH2-CH3 domain of rabbit IgG (Fc) in one open-reading frame to generate sPD1fc, sΔ42PD1fc, PD-L1fc, and PD-L2fc, respectively. The 14APD1 mutant was generated by an overlapping PCR-based technique to introduce a run of 14 alanines into the deletion region using the primer pair 14aPD-1 forward/14aPD-1 reverse. Fusion DNA vaccine plasmids with HIV-1 Gag p24 insert alone or linked to human or murine sΔ42PD1 contain the cytomegalovirus promoter and transcription led by the tPA signal sequence, which improves the adaptive immunogenicity of encoded antigen by DNA vaccines likely due to increased protein expression. PD1 signal sequence is still intact in the construct, thus cleavage for protein translation does affect the overall fusion protein composition. To increase the flexibility of the fusion protein, a linker GGGGSGGGG (nucleotide sequence: GGTGGTGGTTCAGGAGGAGGA) was applied between the sPD1 and HIV-1 p24 gene. Recombinant fusion proteins were produced by transient transfection of 293T cells using polyethylenimine for 72 hours and purified with protein-G agarose (Invitrogen), and quantified using a Micro BCA protein kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Endotoxin contamination was not detected in all protein preparations as tested by the E-TOXATE kit (sensitivity 0.03 endotoxin unit/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Recombinant proteins was detected by western blotting with specific antibodies and analyzed with Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, St Lincoln, NE).

Molecular modeling. The model of human Δ42PD1 complex was built from the original PD1 crystal structure18 (PDB:3B1K) using the INSIGHTII (Molecular Simulations, San Diego, CA), with the Δ42 deletion and β-strands being highlighted.

Quantification of cytokines. 1 × 106 PBMCs were treated with purified proteins of sPD1fc, sΔ42PD1fc or rabbit Fc (20 μg/ml) or 1 × 106 mouse splenocytes treated with msΔ42PD1-p24fc, msPD1-p24fc or p24fc (20 μg/ml) or lipopolysaccharide (100 ng/ml). The concentration of 20 μg/ml is close to 6.7 μg/ml of sPD1 and 25 μg/ml of polyclonal anti-PD1 antibody to achieve their required in vivo effects.49 Supernatants were then harvested for analysis of cytokine release using the Human or Mouse Th1/Th2 FlowCytomix multiplex kit (Bender MedSystems, Burlingame, CA). Data was generated using FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and analyzed by FlowCytomixPro software (Bender MedSystems).

Binding characteristics of sPD1 fusion proteins. 293T cells transiently expressing human or murine PD-L1 and PD-L2 were incubated with 20 μg/ml of purified sPD1fc, sΔ42PD1fc, rabbit Fc, msPD1-p24fc, msΔ42PD1-p24fc or p24fc proteins, and detected with anti-rabbit Fc-conjugated antibody by flow cytometry.

Vaccination of mice. All animal experiments received approval from the Committee on the Use of Live Animals in Teaching and Research, Laboratory Animal Unit, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China. Female Balb/c mice of 5–8 weeks old were used for DNA immunization (or placebo PBS) by intramuscular injection with EP given every 3 weeks at a dose of 20 or 100 μg in 100 μl volume PBS per mouse for three times (Supplementary Figure S4c). Injection of 100 μl PBS alone served as the placebo group. Two weeks after the final immunization, mice were sacrificed, and sera and splenocytes were collected for immune response analysis. Each group contained three to five individual mice with independent immunization studies performed at least twice.

Antibody responses. Specific antibody responses were assessed by ELISA. Briefly, high-affinity protein-binding ELISA plates (BD Biosciences) were coated with HIV-1 p24 protein (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and serially diluted mice sera were added, and antibodies were quantified by goat-horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse IgG1 or IgG2a antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). Data acquired using VICTOR3 1420 Multilabel Counter (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) >2 optical density over control was used for analysis.

Evaluation of HIV-1 Gag p24-specific T cell responses. ELISPOT kit (U-Cytech Biosciences, CM Utrecht, The Netherlands) was used to assess IFN-γ–producing T cells. Briefly, peptide gagAI (AMQMLKDTI; specific for CD8+ T cells) and peptide gag26 (TSNPPIPVGDIYKRWIILGL; specific for CD4+ T cells) were used to stimulate cells for 20 hours and added to IFN-γ ELISPOT plates, with PMA (500 ng/ml) and calcium ionocycin (1 μg/ml) as positive control, or media only as negative control. Peptide pool consisting of 59 members of Gag p24 libraries (each peptide contains 15 amino acids with 10 amino acids overlap) were divided into three pools of 19–20 peptides that span from amino acids 1–87 (pool 1), 77–167 (pool 2), and 157–231 (pool 3) and used to assess epitopic breadth of T cell response. Elispots were identified by an immunospot reader and image analyzer (Thermo Scientific). Major histocompatibility complex class I H2-Kd-AMQMLKDTI (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) tetramer was used to identify p24-specific CD8+ T cell population. Flow cytometric data was acquired and analyzed on a BD Aria III flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

T cell proliferation. Splenocytes were isolated from immunized mice 30 weeks post-immunization, labeled with CFSE (5 μmol/l; Invitrogen), and stimulated with p24 peptide pool (2 μg/ml; donated by National Institutes of Health, catalog: 8117), anti-CD28 antibody (2 μg/ml; eBioscience, San Diego, CA), in the presence of bone marrow-derived DCs at a ratio of 1 DC:10 splenocytes for 5 days. Positive control included anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 antibodies (2 μg/ml). Surface staining occurred for CD3/CD4/CD8 T cell markers, and flow cytometry with FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) was used to acquire CFSE signals on T cells. Percentage of dividing cells were determined as previously described50 and calculated based on the events in each peak (M gates) using the Proliferation tool in FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Cytotoxicity assay. Splenocytes isolated from mice 2 weeks after the last vaccination served as effector cells. Effector cells were stimulated with p24 peptide pool (2 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 antibody (2 μg/ml; eBioscience) for 16 hours before used. AB1 cell line (CellBank Australia, Sydney, Australia) transduced to express HIV-1 Gag served as target cells. A luciferase reporter was also introduced to this AB1-HIV-1-Gag cells. Assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions using the LIVE/DEAD Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity Kit (Invitrogen). Briefly, target cells were pre-stained with DiOC and cocultured with effector cells at varying ratios for 2 hours before all cells were stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentage of dead cells was calculated by subtracting the percentage of propidium iodide+ target only cells for each test sample.

Tumor challenge. Mice were subcutaneously challenged with 5 × 105 AB1-HIV-1-Gag cells. Briefly, a transfer vector pBABE-HIVgag/Luc was inserted with a cytomegalovirus promoter and cotransfected with pCL packaging vector into 293T cells to produce virus particules. Retrovirus-containing supernatants were used to infect AB1 mesothelioma cells21 with puromycin selection and single clones were expanded. Following tumor challenge, in vivo image were taken twice a week to detect the intensity of luciferase on the flank of mice by Xenogen IVIS 100 in vivo imaging system (Xenogen, Alameda, CA).

Virus challenge and plaque assay. Mice 3 weeks post-vaccination were intranasally challenged using modified vaccinia virus that expresses HIV-1 gag and pol genes from attenuated strain TianTan (VTTgagpol) (for 20 μg dose mice group) or virulent strain Western Reserve (WRgagpol) (for 100 μg dose mice group) at 4 × 107 and 2 × 106 plaque-forming units, respectively. Mice were sacrificed 8 days post-challenge to determine virus titers in the lung homogenates, prepared by physical disruption, and cultured on Vero cell monolayer to monitor cytopathic effect over time. Body weight of WRgagpol-infected mice were monitored daily for 8 days before killing.

Statistical analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using the paired two-tailed Student's t-test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were presented as mean values ± SEM of at least two independent experiments (and ≥3 mice per group per experiment) unless indicated.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Purity of recombinant proteins. Figure S2. Schematic representation of Δ42 deletion on human PD1 in complex with PD-L2. Figure S3. Membrane-bound Δ42PD1 can induce proinflammatory cytokines from PBMCs. Figure S4. Vaccination using human sΔ42PD1-p24fc fusion DNA elicited greater immune response. Figure S5. Murine sΔ42PD1 does not interact with PD-L1/L2. Figure S6. msΔ42PD1-p24fc recombinant protein can induce proinflammatory cytokines from murine splenocytes. Figure S7. Antibody response against msΔ42PD1 was not found in mice immunized with msΔ42PD1-p24fc. Figure S8. Comparison of wild-type murine sPD1- and sΔ42PD1-based fusion vaccine in mice. Figure S9. Induction of T cell-activating cytokines by sΔ42PD1fc in PBMCs. Table S1. Primer sequences used. Table S2. Antibodies used. Table S3. Cytokine detection in immunized mice sera.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shanghai TERESA Healthcare Sci-Tech Co., Ltd for providing the electroporation machine, Cecilia Cheng-Mayer, Kwok-Yung Yuen, and David D. Ho for scientific discussion. We thank Faye K.W. Cheung for technical assistance with γ-irradiation. This work was supported by Hong Kong Research Grant Council RGC762209 and RGC762811, Pneumoconiosis Compensation Fund Board grant (to Z.C.), University Development Fund of the University of Hong Kong to AIDS Institute, and by the National Science and Technology Major Project 2012ZX10001-009. The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, Bourque K, Chernova T, Nishimura H, et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1027–1034. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latchman Y, Wood CR, Chernova T, Chaudhary D, Borde M, Chernova I, et al. PD-L2 is a second ligand for PD-1 and inhibits T cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:261–268. doi: 10.1038/85330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:515–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki T, Honjo T. The PD-1-PD-L pathway in immunological tolerance. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao S, Wang S, Zhu Y, Luo L, Zhu G, Flies S, et al. PD-1 on dendritic cells impedes innate immunity against bacterial infection. Blood. 2009;113:5811–5818. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokunina L, Castillejo-López C, Oberg F, Gunnarsson I, Berg L, Magnusson V, et al. A regulatory polymorphism in PDCD1 is associated with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in humans. Nat Genet. 2002;32:666–669. doi: 10.1038/ng1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SC, Yen JH, Tsai JJ, Tsai WC, Ou TT, Liu HW, et al. Association of a programmed death 1 gene polymorphism with the development of rheumatoid arthritis, but not systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:770–775. doi: 10.1002/art.20040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurado JO, Alvarez IB, Pasquinelli V, Martínez GJ, Quiroga MF, Abbate E, et al. Programmed death (PD)-1:PD-ligand 1/PD-ligand 2 pathway inhibits T cell effector functions during human tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2008;181:116–125. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day CL, Kaufmann DE, Kiepiela P, Brown JA, Moodley ES, Reddy S, et al. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature. 2006;443:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature05115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbani S, Amadei B, Tola D, Massari M, Schivazappa S, Missale G, et al. PD-1 expression in acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is associated with HCV-specific CD8 exhaustion. J Virol. 2006;80:11398–11403. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01177-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen C, Ohm-Laursen L, Barington T, Husby S, Lillevang ST. Alternative splice variants of the human PD-1 gene. Cell Immunol. 2005;235:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan B, Nie H, Liu A, Feng G, He D, Xu R, et al. Aberrant regulation of synovial T cell activation by soluble costimulatory molecules in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 2006;177:8844–8850. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SM, Sutherland AP, Zhang Z, Rainbow DB, Quintana FJ, Paterson AM, et al. Overexpression of the Ctla-4 isoform lacking exons 2 and 3 causes autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2012;188:155–162. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistrelli G, Jeannin P, Elson G, Gauchat JF, Nguyen TN, Bonnefoy JY, et al. Identification of three alternatively spliced variants of human CD28 mRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;259:34–37. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanawa H, Ma Y, Mikolajczak SA, Charles ML, Yoshida T, Yoshida R, et al. A novel costimulatory signaling in human T lymphocytes by a splice variant of CD28. Blood. 2002;99:2138–2145. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlin AJ, Clark F, Smith CW. Understanding alternative splicing: towards a cellular code. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:386–398. doi: 10.1038/nrm1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanaraj TA, Clark F. Human GC-AG alternative intron isoforms with weak donor sites show enhanced consensus at acceptor exon positions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2581–2593. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.12.2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lázár-Molnár E, Yan Q, Cao E, Ramagopal U, Nathenson SG, Almo SC. Crystal structure of the complex between programmed death-1 (PD-1) and its ligand PD-L2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10483–10488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804453105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffre O, Nolte MA, Spörri R, Reis e Sousa C. Inflammatory signals in dendritic cell activation and the induction of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:234–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aihara H, Miyazaki J. Gene transfer into muscle by electroporation in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:867–870. doi: 10.1038/nbt0998-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MR, Manning LS, Whitaker D, Garlepp MJ, Robinson BW. Establishment of a murine model of malignant mesothelioma. Int J Cancer. 1992;52:881–886. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorelli M, Livrea P, Defazio G, Ricchiuti F, Pagano E, Trojano M. IFN-beta1a modulates the expression of CTLA-4 and CD28 splice variants in human mononuclear cells: induction of soluble isoforms. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2001;21:809–812. doi: 10.1089/107999001753238042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebbar M, Jeannin P, Magistrelli G, Hatron PY, Hachulla E, Devulder B, et al. Detection of circulating soluble CD28 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, primary Sjögren's syndrome and systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:388–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02427.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CK, Lit LC, Tam LS, Li EK, Lam CW. Aberrant production of soluble costimulatory molecules CTLA-4, CD28, CD80 and CD86 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:989–994. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Wang K, Zhong X, Dai Y, Wu A, Li Y, et al. Plasma sCD28, sCTLA-4 levels in neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis during relapse. J Neuroimmunol. 2012;243:52–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koup RA, Douek DC. Vaccine design for CD8 T lymphocyte responses. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1:a007252. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Huang Y, Zhao X, Ba L, Zhang W, Ho DD. Design, construction, and characterization of a multigenic modified vaccinia Ankara candidate vaccine against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C/B'. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:412–421. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181651bb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhang M, Zhou C, Zhao X, Iijima N, Frankel FR. Novel vaccination protocol with two live mucosal vectors elicits strong cell-mediated immunity in the vagina and protects against vaginal virus challenge. J Immunol. 2008;180:2504–2513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai B, Yang L, Yang H, Hu B, Baltimore D, Wang P. HIV-1 Gag-specific immunity induced by a lentivector-based vaccine directed to dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20382–20387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911742106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roake JA, Rao AS, Morris PJ, Larsen CP, Hankins DF, Austyn JM. Dendritic cell loss from nonlymphoid tissues after systemic administration of lipopolysaccharide, tumor necrosis factor, and interleukin 1. J Exp Med. 1995;181:2237–2247. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevejo JM, Marino MW, Philpott N, Josien R, Richards EC, Elkon KB, et al. TNF-alpha -dependent maturation of local dendritic cells is critical for activating the adaptive immune response to virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12162–12167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211423598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong EC, Vieira PL, Kalinski P, Schuitemaker JH, Tanaka Y, Wierenga EA, et al. Microbial compounds selectively induce Th1 cell-promoting or Th2 cell-promoting dendritic cells in vitro with diverse th cell-polarizing signals. J Immunol. 2002;168:1704–1709. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhweide R, Van Damme J, Ceuppens JL. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin 6 synergistically induce T cell growth. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:1019–1025. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detournay O, Mazouz N, Goldman M, Toungouz M. IL-6 produced by type I IFN DC controls IFN-gamma production by regulating the suppressive effect of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Ayyavoo V, Bagarazzi ML, Chattergoon M, Boyer JD, Wang B, et al. Development of a multicomponent candidate vaccine for HIV-1. Vaccine. 1997;15:879–883. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanyan MG, Kim JJ, Trivedi N, Wilson DM, Monzavi-Karbassi B, Morrison LD, et al. CD86 (B7-2) can function to drive MHC-restricted antigen-specific CTL responses in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;162:3417–3427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shedlock DJ, Weiner DB. DNA vaccination: antigen presentation and the induction of immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68:793–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Cheung AK, Tan Z, Wang H, Yu W, Du Y, et al. 2013PD1-based DNA vaccine amplifies HIV-1 CD8+ T cells in mice. J Clin Investin the press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Trumpfheller C, Finke JS, López CB, Moran TM, Moltedo B, Soares H, et al. Intensified and protective CD4+ T cell immunity in mice with anti-dendritic cell HIV gag fusion antibody vaccine. J Exp Med. 2006;203:607–617. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idoyaga J, Lubkin A, Fiorese C, Lahoud MH, Caminschi I, Huang Y, et al. Comparable T helper 1 (Th1) and CD8 T-cell immunity by targeting HIV gag p24 to CD8 dendritic cells within antibodies to Langerin, DEC205, and Clec9A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2384–2389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019547108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho D, Mourão-Sá D, Joffre OP, Schulz O, Rogers NC, Pennington DJ, et al. Tumor therapy in mice via antigen targeting to a novel, DC-restricted C-type lectin. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2098–2110. doi: 10.1172/JCI34584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Wu C, Song J, Wang J, Zhang E, Liu H, et al. DNA immunization with fusion of CTLA-4 to hepatitis B virus (HBV) core protein enhanced Th2 type responses and cleared HBV with an accelerated kinetic. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeituni AE, Jotwani R, Carrion J, Cutler CW. Targeting of DC-SIGN on human dendritic cells by minor fimbriated Porphyromonas gingivalis strains elicits a distinct effector T cell response. J Immunol. 2009;183:5694–5704. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao LA, Wu L, Khan AS, Hokey DA, Yan J, Dai A, et al. Combined effects of IL-12 and electroporation enhances the potency of DNA vaccination in macaques. Vaccine. 2008;26:3112–3120. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontiveros F, Wilson EB, Livingstone AM. Type I interferon supports primary CD8+ T-cell responses to peptide-pulsed dendritic cells in the absence of CD4+ T-cell help. Immunology. 2011;132:549–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S, Perera LP, Terabe M, Ni L, Waldmann TA, Berzofsky JA. IL-15 as a mediator of CD4+ help for CD8+ T cell longevity and avoidance of TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5201–5206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801003105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Rossum A, Krall R, Escalante NK, Choy JC. Inflammatory cytokines determine the susceptibility of human CD8 T cells to Fas-mediated activation-induced cell death through modulation of FasL and c-FLIP(S) expression. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:21137–21144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.197657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuthrich M, Filutowicz HI, Warner T, Deepe GS, Jr, Klein BS. Vaccine immunity to pathogenic fungi overcomes the requirement for CD4 help in exogenous antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells: implications for vaccine development in immune-deficient hosts. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1405–1416. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onlamoon N, Rogers K, Mayne AE, Pattanapanyasat K, Mori K, Villinger F, et al. Soluble PD-1 rescues the proliferative response of simian immunodeficiency virus-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells during chronic infection. Immunology. 2008;124:277–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons AB. Analysing cell division in vivo and in vitro using flow cytometric measurement of CFSE dye dilution. J Immunol Methods. 2000;243:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.