Abstract

Mushrooms are commercially cultivated over the world and safe for human consumption, except in those with known allergies. Among the thousands of mushroom species identified, few are considered to be edible. Mushroom hunting has emerged as an adventure and recreational activity in recent decades. Wild forms of mushrooms are often poisonous and visually mimic the edible ones, thus leading to mistaken harvesting, consumption, and toxicities. In literature, various systemic toxic syndromes associated with mushroom poisoning have been described. We report four members of a family with muscarinic manifestations after accidental consumption of poisonous mushrooms. The Clitocybe species of mushrooms they consumed resulted in their muscarinic toxicity. Patients with muscarinic mushroom toxicity have early onset of symptoms and they respond well to atropine and symptomatic supportive care.

Keywords: Atropine, clitocybe, mushroom poisoning, muscarinic poisoning

INTRODUCTION

Mushrooms, the fleshy fruit bodies, are considered to be a delicacy among various ethnic groups over the world. Mushroom poisoning or mycetism occur from ingestion of toxins present in mushrooms. Most mushrooms other than the few edible species are poisonous for consumption. At times, poisonous mushrooms resembling edible mushrooms are consumed resulting in toxicity or poisoning. Various toxic syndromes associated with mushroom consumption have been described in literature.[1] We report four members of a family presenting with muscarinic manifestations after ingestion of poisonous mushrooms by mistaken identity. Although we were unable to collect the mushrooms, their description matched to that of Clitocybe species. The consumption of Clitocybe species of mushrooms is often associated with early onset muscarinic toxicity.[2]

CASE REPORT

We have this report on four members (three females and one male) of a family who reported to the emergency department in the evening with symptoms and signs of muscarinic toxicity. That afternoon they consumed mushrooms which were plucked by them that morning from their farmland. The mushrooms were found as fresh crops on a wooden log in their farm. After 2-3 hours of consuming the mushroom dish, they found themselves to be irritable, exhausted, with abdominal cramps, and diarrhea.

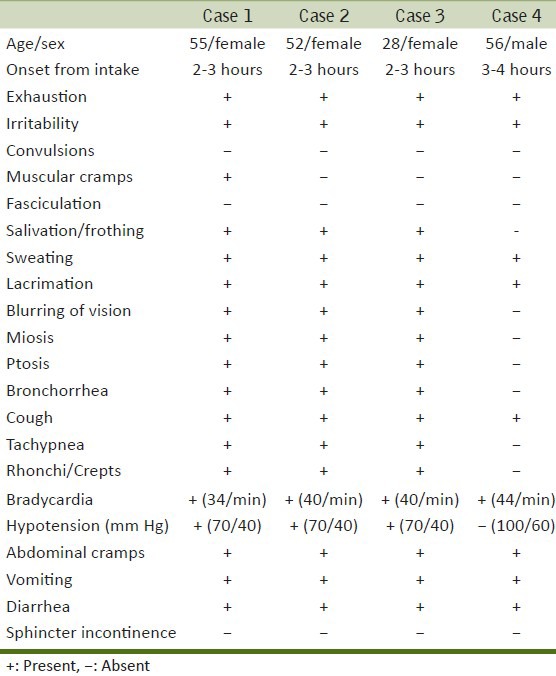

The female patients had severe muscarinic symptoms and signs. Systemic muscarinic manifestations such as exhaustion, irritability, muscular cramps, salivation, frothing from mouth, sweating, lacrimation, blurring of vision, miosis, ptosis, bronchorrhea, cough, wheeze, tachypnea, rhonchi, bradycardia, hypotension, abdominal cramps, vomiting, and diarrhea were observed in all of them. The male patient had milder muscarinic toxic symptoms and signs. The clinical symptoms and signs of these patients are represented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Symptoms and signs recorded in cases with mushroom poisoning

Patients with severe muscarinic manifestations were administered intravenous crystalline fluids and bolus injection of atropine (3 mg). As they continued to have muscarinic features and persistent bradycardia with hypotension, they were shifted to intensive care unit for further observation and treatment. Aggressive hemodynamic monitoring along with continuous infusion of atropine (0.5-1 mg/h) and fluid resuscitation were initiated. Over the next 8-10 h all of them were free of symptoms and medications were tapered off. Investigations showed mild leukocytosis, normal electrolyte, arterial blood gas levels, and renal and hepatic biochemistry; and bradycardia in electrocardiogram. After 48 h of observation they were discharged from the hospital. The patient with mild toxicity improved with crystalline fluids and was discharged within 6 h from hospital.

In this report, the typical muscarinic manifestations and history of mushroom intake clinched the diagnosis. We were unable to collect the actual mushrooms for identification, but the description given by the patients matched to Clitocybe species of mushrooms.

DISCUSSION

Mushroom poisoning or mycetism is caused by ingestion of toxins present in mushrooms. Among various species of mushrooms most are not edible due to the toxicities they produce.[1,2] In this report the patients presented with early onset muscarinic syndrome after mushroom ingestion. Three of them had severe muscarinic features and they responded well to symptomatic treatment with atropine and fluids. The poisoning resulted from consumption of mushrooms belonging to Clitiocybe species. Clitocybe species mushrooms are conical and mostly grow as crops on wooden pieces during rainy season.[1]

Muscarine, a water-soluble toxin was first isolated from the mushroom species Amanita muscaria. The muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) are named from M1-M5 belong to the family of G-protein-coupled receptors (‘G proteins’). They are involved with the various large autonomic physiological functions of the human body.[3] The usual symptoms and signs associated with muscarinic stimulation are exhaustion, irritability, muscular cramps, salivation, frothing, sweating, lacrimation, blurring of vision, miosis, ptosis, bronchorrhea, cough, tachypnea, bronchospasm, bradycardia, hypotension, abdominal cramps, vomiting, and diarrhea.[3,4]

Fatal muscarinic mushroom poisoning due to Clitocybe and Inocybe species have been described in literature.[4,5,6] Toxicities usually occur due to accidental consumption of toxic mushrooms by mistaken identity.

Based on the onset of presentation of clinical features, syndromes are classified as early onset, late onset and delayed onset syndromes. Early onset is of less than 6 h, late onset is between 6-24 h, and delayed onset is of more than 1 day.[2,7,8] Among early onset syndromes, four are neurotoxic, two are gastrointestinal, and two are allergic. The late onset syndromes are hepatotoxic, accelerated nephrotoxic, and erythromelalgia. The three delayed onset syndromes are delayed nephrotoxic, delayed neurotoxic, and rhabdomyolysis syndrome. Various toxic syndromes described in mushroom poisoning are phalloides syndrome, orellanus syndrome, gyromitra syndrome, muscarin syndrome, pantherina syndrome, psilocybin syndrome, gastrointestinal syndrome, paxillus syndrome, and coprine syndrome.[2,7,8]

There are no specific antidotes available for muscarinic mushroom toxicity. As in this report, patients with severe symptoms and signs may require atropine, hemodynamic monitoring and aggressive fluid management for the reversal of symptoms. Mild muscarinic toxicities do not require any specific treatment and adequate hydration is good enough in its management.[4,7,9,10]

CONCLUSIONS

Mushrooms are safe, nutritious, and delicious to consume. But consumption of poisonous mushrooms can result in severe fatal toxicities. Muscarinic mushroom toxicity has early onset of symptoms and respond well to atropine and symptomatic supportive care.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deshmukh SK, Natarajan K, Verekar SA. Poisonous and hallucinogenic mushrooms of India. Int J Med Mushr. 2006;8:251–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saviuc P, Danel V. New syndromes in mushroom poisoning. Toxicol Rev. 2006;25:199–209. doi: 10.2165/00139709-200625030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caulfield MP, Birdsall NJ. International union of pharmacology. XVII. Classification of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:279–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stallard D, Edes TE. Muscarinic poisoning from medications and mushrooms. A puzzling symptom complex. Postgrad Med. 1989;85:341–5. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1989.11700558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pauli JL, Foot CL. Fatal muscarinic syndrome after eating wild mushrooms. Med J Aust. 2005;182:294–5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lurie Y, Wasser SP, Taha M, Shehade H, Nijim J, Hoffmann Y, et al. Mushroom poisoning from species of genus Inocybe (fiber head mushroom): A case series with exact species identification. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2009;47:562–5. doi: 10.1080/15563650903008448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz JH. Syndromic diagnosis and management of confirmed mushroom poisonings. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:427–36. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000153531.69448.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chew KS, Mohidin MA, Ahmad MZ, Tuan Kamauzaman TH, Mohamad N. Early onset muscarinic manifestations after wild mushroom ingestion. Int J Emerg Med. 2008;1:205–8. doi: 10.1007/s12245-008-0054-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldfrank LR. Mushrooms. In: Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE, editors. Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011. pp. 1522–36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erguven M, Yilmaz O, Deveci M, Aksu N, Dursun F, Pelit M, et al. Mushroom poisoning. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:847–52. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]