Abstract

Background

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is considered the most common liver disease affecting 15–25% of the general population.

Aims

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of NAFLD and the relationship between insulin sensitivity and NAFLD in grade III high and very high cardiovascular additional risk essential hypertensive patients according to the circadian blood pressure (BP) rhythm.

Method

This four-year prospective study was conducted at the Department of Internal Medicine at Cluj-Napoca’s Diagnosis and Treatment Centre in Romania. The study included grade III essential hypertensive patients. Hypertensive patients were divided into four groups according to the diurnal index (DI) from ABPM monitoring: dipper (D), non-dipper (ND), reverse-dipper (RD), and extreme-dipper (ED). All hypertensive patients underwent 24 ABPM, blood tests and abdominal ultrasonography for the diagnosis of fatty liver disease.

Results

Thirty-five hypertensive patients were included in the study, with 31.42% ND, 11.43% RD, 8.57% ED and 48.57% D. The prevalence of NAFLD was significantly higher in ND, RD and ED when compared to D. When compared to the dipper group of hypertensive patients a statistically significantly higher level of plasma insulin was observed: in non-dipper [86.3±17.9pmol/l vs. 62.2±203pmol/l, p<0.05], in reverse dipper [88.3±18.6pmol/l vs. 62.2±20.3pmol/l] and in extreme-dippers [86.7±16.88pmol/l vs. 62.2±20.3 pmol/l, p<0.05].

Conclusion

The altered dipping status (ND, RD, ED) of hypertension associated with a higher insulin resistance could be the pathogenetic link between the NAFLD and altered blood pressure status. Altered BP status could be a marker of NAFLD in hypertensive patients.

Keywords: Essential hypertension, primary non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD, circadian blood pressure rhythm, insulin resistance

What this study adds:

Little is know about this subject

The altered dipping status of hypertension associated with a higher insulin resistance could be the pathogenetic link between the NAFLD and altered blood pressure status.

Altered BP status could be a marker of NAFLD in hypertensive patients.

Background

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) represents a spectrum starting from fatty liver, fatty liver and inflammation to evidence of damage to hepatocytes and can progress to cirrhosis or in the most extreme form of NAFLD can progress to hepatocellular carcinoma or liver failure.1 Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is considered the most common liver disease affecting 15–25% of the general population.2 Primary NAFLD results from insulin resistance and NAFLD is considered as part of the metabolic syndrome.3-6 Essential hypertension is considered an insulin resistant state7,8 and through the basis of insulin resistance mechanisms, recent studies consider NAFLD as an early mediator of atherosclerosis9,10 and an increased cardiovascular risk factor.11

The aim of the present study was to investigate the prevalence of NAFLD in grade III high and very high cardiovascular additional risk hypertensive patients according to circadian BP rhythm and to investigate the relationship between insulin sensitivity and NAFLD in essential hypertensive patients according to the circadian BP rhythm.

Method

Study population

From November 2005 to December 2009 a prospective study was conducted. The study included consecutive eligible adult hypertensive patients admitted to the Department of Internal Medicine at Cluj-Napoca’s Diagnosis and Treatment Centre.

The study included patients of either sex with grade III essential hypertension and additional high and very high global cardiovascular risk. Essential hypertension was defined according to the ESC/ESH 2007 guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of European Society of Cardiology Guidelines Committee12 as office sitting systolic BP [SBP] of ≥180 mmHg and/or office diastolic BP [DBP] ≥110mmHg measured by mercury sphygmomanometer, at rest in a sitting position in at least three separate casual measurements within the last month.

Patients with mild or moderate essential hypertension or suspected secondary hypertension were excluded. Also patients with chronic alcoholism, diabetic mellitus, evidence of cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, hepatic disease, and patients with previous drug-induced fatty liver treatment (corticoids, chronic salicylates, tricyclic antidepressants, tamoxifen, tetracyclines, synthetic oestrogens and amiodarone)13,14 were excluded from the study.

Thirty-five hypertensive patients gave their informed consent before taking part in the study, completed the inclusion criteria and were therefore enrolled in the study.

All hypertensive patients underwent 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) (for systolic and diastolic BP evaluation), blood tests and abdominal ultrasonography.

The ABPM was performed with ABPM-04, 99/BP411 - Medibase. Before the beginning of ABPM, BP was measured with a mercury sphygmomanometer, with the patient seated for at least 10 minutes. The arm with higher BP values at sphygmomanometer evaluation was chosen for ABPM. In order to reduce errors during the day all patients were asked to ensure that the arm was always parallel to the trunk when the cuff was inflated. Readings were obtained automatically at 15 minute intervals from 7:00 am to 22:00 pm and 30-minute intervals from 22:00 pm to 7:00 am. All the measurements were performed by the same investigator, using the same equipment, both at the beginning of the study and during the follow-up.

Hypertensive patients were divided into four groups according to the diurnal index (DI) from ABPM monitoring: dipper (D), non-dipper (ND), reverse-dipper (RD), and extreme-dipper (ED). The diurnal index = 100 X (the average of the diurnal values – the average of the night values)/the average of the diurnal values (N >10%). Dipper patients were defined as 10%≤DI<20%, non-dipper defined as 0 ≤DI<10%, extreme-dipper defined as DI≥20%, reversedipper defined as DI<0.15

The diagnosis of fatty liver, was established using the noninvasive method of abdominal ultrasound followed by the exclusion of the secondary causes of hepatic steatosis: a history of another known liver disease, alcohol intake of 30g/day or more for males and 20g/day or more for females, a positive serology for hepatitis B or C virus or ingestion of drugs known to produce hepatic steatosis. The liver ultrasonography scanning was performed by standard criteria16,17 by the same investigator, in all patients in the morning , after overnight fasting, using the same equipment (ESAOTE My Lab, with a 3.5-MHz transducer). The presence of liver steatosis was graded semi-quantitatively according to a previously reported scale:18 0 - absent, 1 - mild, 2 - moderate and 3 - severe steatosis.

In all hypertensive patients who fasted overnight for biochemical and metabolic profile, blood samples were evaluated by standardised routine laboratory techniques.

Serum triglycerides, total, and HDL cholesterol, glucose, insulin, alanine amino transferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels were measured, using routine automated assay methods. Reference range of values, are 0–40 IU/l for ALT, 0–37 IU/l for AST, 6–20 mIU/ml for insulinaemia, 0–50 IU/l for cGT, 70–170 mg/dl for triglycerides, 60–110 mg/dl for glucose, and up to 200 mg/dl for total cholesterol.

Insulin resistance was calculated by the homeostasis monitoring assessment (HOMA) formula. The HOMA index was calculated as the product of the fasting plasma insulin level (μU/mL) and the fasting plasma glucose level (mmol/L), divided by 22.5.19,20

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means, SD, ranges and percentages, were used to characterise the study subjects. Statistical significance between groups was assessed by a Student‘s t test in normally distributed for independent samples. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17 and the Statistica 8 program.

Results

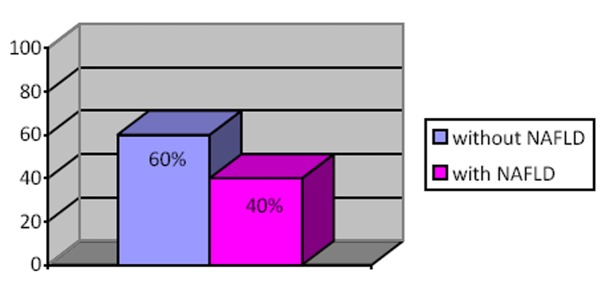

NAFLD was present in 14 hypertensive patients (40%) with grade III essential hypertension with high and very high additional cardiovascular risk as reported in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The prevalence of NAFLD in hypertensive patients.

According to diurnal index from ABPM the 35 hypertensive patients were divided into four groups as follows: 48.57% (n=17) patients as dippers, 31.42% (n=11) patients as nondipper, 11.43% (n=4) patients as reverse- dippers and 8.57% (n=3) patients as extreme-dippers.

No statistically significant differences were observed between the four groups of patients in terms of demographic baseline characteristics (p>0.05).

Baseline demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by blood pressure circadian rhythm.

| Variable Dippers | Dippers (n=17) | Non-dippers (n=11) | Reverse -dippers (n=4) | Extreme dippers (n=3) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender: absolute | |||||

| Male | 8 (47.05%) | 7(63.63%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (33.33%) | ns |

| Female | 9 (52.95%) | 4(36.37%) | 3 (75%) | 2 (66.66%) | ns |

| Age: means±SD | |||||

| Male (years) | 51.6±11.3 | 53.8±12.22 | 54.21±12.02 | 53.87±11.62 | ns |

| Female (years) | 50.2±9.78 | 52.2±10.84 | 54.66±8.99 | 52.33±9.79 | ns |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 32.42±3.99 | 35.32±4.55 | 36.3±7.77 | 35.5±3.87 | ns |

| Mean 24h SBP (mmHg) | 143.5±14.8 | 143.5±14.75 | 144.3±17.44 | 145.8±15.5 | ns |

| Mean 24h DBP (mmHg) | 88.7±11.05 | 86.3±12.06 | 87.5±12.41 | 85.3±12.77 | ns |

| Triglyceri des (mg/dl) | 108.5±33.4 | 111.5±35.21 | 110.8±30.77 | 107.3±32.45 | ns |

| Total cholest (mg/dl) | 220.3±45.2 | 205.66±44.31 | 208.5±41.02 | 210.8±42.03 | ns |

| HDL cholest (mg/dl) | 47.5±3.22 | 46.8±4.04 | 46.2±3.71 | 48.3±4.57 | ns |

| ALT (U/l) 19.4± | 19.4±7.77 | 22.4±8.31 | 23.9±6.98 | 24.5±8.87 | ns |

| AST (U/l) 22.8± | 22.8±8.75 | 20.4±8.53 | 22.3±7.93 | 20.6±8.35 | ns |

| GGT (U/l) 23.9± | 23.9±11.1 | 25.4±12.3 | 25.5±10.7 | 20.8±8.33 | ns |

| SD = standard deviation, SBP= systolic blood pressure, DBP= diastolic blood pressure, LDL=low-density lipoprotein, HDL=high-density lipoproteins, ALT=alanine amino transferase, AST=aspartate aminotransferase, GGT= gamma-glutamyl transferase | |||||

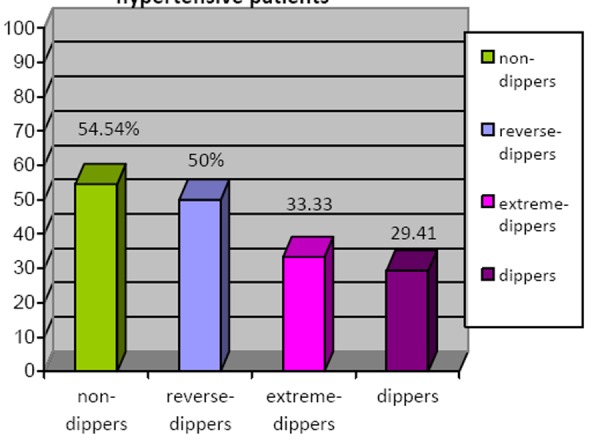

The prevalence of NAFLD was significantly higher in the non-dipper hypertensive patients group 54.54% (n=6), the reverse-dipper hypertensive patients group 50% (n=2) and the extreme-dipper hypertensive patients group 33.33% (n=1) compared to the dipper hypertensive patients group 29.41% (n=5)( p<0.05) as reported in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The prevalence of NAFLD in hypertensive patients.

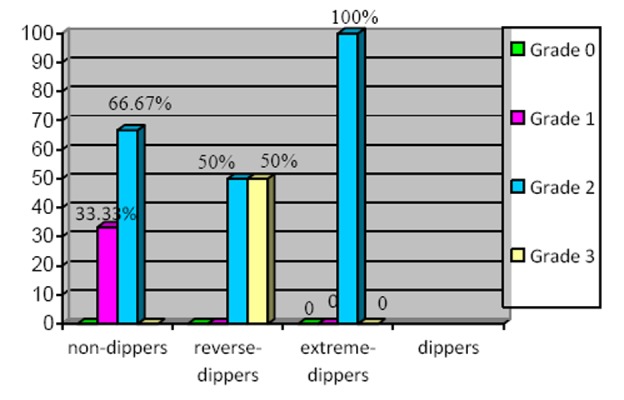

The prevalence of liver steatosis grades according to the diurnal status of dipper, non-dipper, reverse-dipper, extreme-dipper was observed as presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The prevalence of ultrasonographic grades of NAFLD in hypertensive patients.

A statistically significantly higher level of plasma insulin was observed in the group of non-dipper hypertensive patients when compared to the dipper hypertensive patients [86.3±17.9pmol/l vs. 62.2±203pmol/l, p<0.05] in reversedipper hypertensive patients when compared to dipper hypertensive patients [88.3±18.6pmol/l vs.62.2±20.3 pmol/l] and in extreme-dipper hypertensive patients versus dipper hypertensive patients [86.7±16.88pmol/l vs. 62.2±20.3 pmol/l, p<0.05]. In the non-dipper, reversedipper, extreme-dipper hypertensive patients a significantly higher level of the HOMA index was observed when compared to the dipper hypertensive patients: in nondipper vs. dipper: 3.7±1.03 vs.2.2±0.88, p<0.05], in reversedipper vs. dipper 4±0.99 vs. 2.2±0.88,p<0.05] and in extreme-dipper vs. dipper 3.6±0.97 vs.2.2±0.88, p<0.05].

Discussion

This study revealed a significant statistical difference of the NAFLD prevalence, between the altered dipping status (nondipper, reverse-dipper, and extreme-dipper) and the normal dipping status of hypertensive patients. A higher prevalence of the NAFLD was observed in non-dipper hypertensive patients, followed by reverse-dipper and extreme-dipper when compared with dipper hypertensive patients. The liver steatosis grade was more severe in the reverse-dipper group of hypertensive patients who presented moderate and severe steatosis. All extreme-dipper hypertensive patients presented a moderate grade of steatosis of disease. Grade III essential hypertensive patients with the altered dipping profile (ND, RD, ED) revealed a statistically significant higher level of plasma insulin when compared to the dipper group of hypertensive patients suggesting that insulin resistance could play a role in the tendency of a greater end organ damage in hypertensive patients with an altered BP circadian rhythm (non-dipper, reverse-dipper, extreme-dipper).21,22

The association between the non-dipper status and insulin resistance that was observed in the present study has already been demonstrated.23,24 Altered dipping status (non-dipping, reverse-dipping, extreme-dipping) have been shown in population-based studies to correlate with target organ damage, including cardiovascular morbidity and mortality25,28 progression of pre-existing renal disease29,30 and cerebrovascular disease.31 The small number of the patients included was a study limitation. Additional research is needed to identify the specific ways in which insulin resistance links the NAFLD and altered BP status.

Conclusion

The altered BP status of hypertension associated both a higher insulin resistance and a higher prevalence of NAFLD. This brings us to the conclusion that insulin resistance could be the pathogenic link between the NAFLD and altered BP status. Altered BP status could be a marker of the NAFLD in hypertensive patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

No funding was obtained by pharmaceutical companies to carry out this study. None of the authors have any conflict of interest. All the authors were involved in the data collection and analysis.

Footnotes

PEER REVIEW

Not commissioned. Externally peer reviewed.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

FUNDING

There was no source of funding

ETHICS COMMITTEE APPROVAL

The University Ethics Committee approved the study design

Please cite this paper as: Latea L, Negrea S, Bolboaca S. Primary non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in hypertensive patients. AMJ 2013, 6, 6, 325-330. http//dx.doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2013.1648

References

- 1.Younossi ZM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. A manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008 Oct;75(10):721–8. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75.10.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams LA, Lindor KD. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Epidemiol. 2007 Nov;17(11):863–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchesini G, Brizi M, Morselli-Labate AM, Bianchi G, Bugianesi E, McCullough AJ, Forlani G, Melchionda N. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistance. Am J Med. 1999 Nov;107(5):450–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stranges S, Trevisan M, Dom JM, Dmochowski J, Donahue RP. Body fat distribution, liver enzymes, and risk of hypertension: evidence from the Western New York Study. Hypertension. 2005 Nov;46(5):1186–93. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000185688.81320.4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akbar DH, Kawther AH. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome: what we know and what we dont’t know. Med Sci Monit. 2006 Jan;12(1):RA23–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim CH, Younossi ZM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008 Oct;75(10):721–8. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75.10.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrannini E, Buzzigoli G, Bonadonna R, Giorico MA, Oleggini M, Graziadei L, Pedrinelli R, Brandi L, Bevilacqua S. Insulin resistance in essential hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1987 Aug 6;317(6)(7):350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198708063170605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamounier-Zepter V, Ehrhart-Bornstein M, Bornstein S. Insulin resistance in hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Sep;20(3):355–67. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Targher G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, the metabolic syndrome and the risk of cardiovascular disease: the plot thickens. Diabet Med. 2007 Jan;24(1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abel T, Fehér J. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk. [Article in Hungarian] Orv Hetil. 2008 Jul 13;149(28):1299–305. doi: 10.1556/OH.2008.28418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donati G, Stagni B, Piscaglia F, Venturoli N, Morselli-Labate AM, Rasciti L, Bolondi L. Increased prevalence of fatty liver in arterial hypertensive patients with normal liver enzymes: role of insulin resistance. Gut. 2004 Jul;53(7):1020–3. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.027086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension, The task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology. 2007 European Society of Hypertension - European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2007 Jun;28(12):1462–536. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fromenty B, Pessayre D. Inhibition of mitochondrial beta-oxidation as a mechanism of hepatotoxicity. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;67:101–54. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berson A, De Beco V, Lettéron P, Robin MA, Moreau C, El Kahwaji J, Verthier N, Feldmann G, Fromenty B, Pessayre D. Steatohepatitis-inducing drugs causemitochondrial dysfunction and lipid peroxidation in rat hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 1998 Apr;114(4):764–74. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70590-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kario K, Schwartz JE, Pickering TG. Changes of Nocturnal Blood Pressure Dipping Status in Hypertensives by Nighttime Dosing of á-Adrenergic Blocker, Doxazosin Results from the HALT Study. Hypertension. 2000 Mar;35(3):787–94. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.3.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saverymuttu SH, Joseph AE, Maxwell JD. Ultrasound scanning in the detection of hepatic fibrosis and steatosis. BMJ. 1986;292:13–15. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6512.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Hoek B. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a brief review. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39(1):56–59. doi: 10.1080/00855920410011013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angelico F, Del Ben M, Conti R, Francioso S, Feole K, Maccioni D, Antonini TM, Alessandri C. Nonalcoholic fatty liver syndrome: a hepatic consequence of common metabolic diseases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003 May;18(5):588–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.02958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tresaco B, Bueno G, Pineda I, Moreno LA, Garagorri JM, Bueno M. Homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) index cut-off values to identify the metabolic syndrome in children. J Physiol Biochem. 2005 Jun;61(2):381–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03167055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuhisa M, Yamasaki Y, Emoto M, Shimabukuro M, Ueda S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. A novel index of insulin resistance determined from the homeostasis model assessment index. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007 Jul;77(1):151–4. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sega R, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Cesana G, Corrao G, Grassi G, Mancia G. Prognostic Value of Ambulatory and Home Blood Pressures Compared With Office Blood Pressure in the General Population: Follow-Up Results From the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate e Loro Associazioni (PAMELA) Study. Circulation. 2005 Apr 12;111(14):1777–83. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160923.04524.5B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Routledge FS, McFetridge-Durdle JA, Dean CR. Night-time blood pressure patterns and target organ damage: a review. Can J Cardiol. 2007 Feb;23(2):132–8. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70733-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Afsar B, Sezer S, Elsurer R, Ozdemir FN. Is HOMA index a predictor of nocturnal nondipping in hypertensives with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus? Clinical Methods and Pathophysiology. Blood Press Monit. 2007 Jun;12(3):133–9. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3280b08379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li I, Soonthornpun S, Chongsuvivatwong V. Association between circadian rhythm of blood pressure and glucose tolerance status in normotensive, non-diabetic subjects. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008 Dec;82(3):359–63. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mancia G, Omboni S, Parati G, Clement DL, Haley WE, Rahman SN, Hoogma RP. Twenty-four hour ambulatory blood pressure in the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) study. J Hypertens. 2001 Oct;19(10):1755–63. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200110000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuspidi C, Macca G, Sampieri L, Fusi V, Severgnini B, Michev I, Salerno M, Magrini F, Zanchetti A. Target organ damage and non-dippping pattern. J Hypertens. 2001 Sep;19(9):1539–45. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuspidi C, Meani S, Salerno M, Valerio C, Fusi V, Severgnini B, Lonati L, Magrini F, Zanchetti A. Cardiovascular target organ damage in essential hypertensives with or without reproducible nocturnal fall in blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2004 Feb;22(2):273–80. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200402000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Routledge F, McFetridge-Durdle J. Nondipping blood pressure patterns among individuals with essential hypertension: A review of the literature. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007 Mar;6(1):9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farmer CK, Goldsmith DJ, Quin DJ, Dallyn P, Cox J, Kingswood JC, Sharpstone P. Progression of diabetic nephropathy: is diurnal blood pressure rhythm as important as absolute blood pressure level? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998 Mar;13(3):635–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.3.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lurbe E, Redon J, Kesani A, Pascual JM, Tacons J, Alvarez V, Batlle D. Increase in nocturnal blood pressure and progression to microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2002 Sep 12;347(11):797–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kario K, Pickering TG, Matsuo T, Hoshide S, Schwartz JE, Shimada K. Stroke prognosis and abnormal nocturnal blood pressure falls in older hypertensives. Hypertension. 2001 Oct;38(4):852–7. doi: 10.1161/hy1001.092640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]