Abstract

Middle-aged and older adults often experience several simultaneously occurring chronic conditions or “multiple morbidity” (MM). The task of both managing MM and preventing chronic conditions can be overwhelming, particularly in populations with high disease burdens, low socioeconomic status, and health care provider shortages. This article sought to understand Appalachian residents’ perspectives on MM management and prevention. Forty-one rural Appalachian residents aged 50 and above with MM were interviewed about disease management and colorectal cancer (CRC) prevention. Transcripts were examined for overall analytic categories and coded using techniques to enhance transferability and rigor. Participants indicate facing various challenges to prevention due, in part, to conditions within their rural environment. Patients and providers spend significant time and energy on MM management, often precluding prevention activities. This article discusses implications of MM management for CRC prevention and strategies to increase disease prevention among this rural, vulnerable population burdened by MM.

Keywords: chronic conditions, prevention, rural, vulnerable elders

Multiple Morbidity (MM): An Increasing and Serious Trend

MM, two or more co-occurring chronic health conditions, has become the norm among middle-aged and older adults (Fortin, Bravo, Hudon, Vanasse, & Lapointe, 2005). The experience of MM varies between individuals, with some experiencing few or no symptoms and others experiencing major symptoms. The prevalence of MM increases with age, with estimates for those aged between 45 and 64 ranging from 35% to 93%, and for those aged 65 and above ranging from 63% to nearly 100% (Fortin et al., 2005; Van den Akker, Buntinx, Metsemakers, Roos, & Knottnerus, 1998). Such high rates of MM have serious implications for medical expenditures, practice patterns, and the long-term health of those affected by MM. Per capita medical expenditures among people with varying chronic conditions found that people with one chronic condition had 1.5 times the expenditures of those with no chronic conditions, and those with two or more chronic conditions had five times the medical expenditures of those with no chronic conditions (Rice & LaPlante, 1992). Other studies have expanded on this finding, demonstrating that as the number of conditions increases, out-of-pocket expenditures expand exponentially (Schoenberg, Kim, Edwards, & Fleming, 2007).

MM also has negative implications for clinical outcomes and health care provision. Medicare data demonstrate an association between MM and inpatient admissions and hospitalizations with preventable complications (Wolff, Starfield, & Anderson, 2002). MM repeatedly has been associated with an increased risk of mortality, loss of functioning, psychological distress, disability, and use of health services (Cornoni-Huntley, Foley, & Guralnik, 1991). From the physician perspective, managing MM can be quite demanding and complex prioritization decisions are often required (Piette & Kerr, 2006). For patients with MM, coordination of multiple medical regimens can be time consuming and challenging (Vogeli et al., 2007), with barriers to optimal disease management ranging from pain, fatigue, transportation, and logistical problems to financial limitations, lack of insurance, depression, and poor physician communication (Jerant, Friederichs-Fitzwater, & Moore, 2005). MM can be especially challenging when one condition, or its treatment, aggravates another, or when medications regimens become complex or interact (Bayliss, Steiner, Fernald, Crane, & Main, 2003). Even when conditions do not interact, additional conditions can create competing priorities and financial and time demands, making optimal self-care for any one condition more challenging (Piette & Kerr, 2006). Despite these management challenges, the long-term prognosis for living with chronic conditions is improving, increasing the importance of preventing, delaying, or controlling the development of new conditions. Many, if not all, of the challenges of MM management similarly obstruct prevention activities (Katz, Wewers, Single, & Paskett, 2007).

MM Management and Disease Prevention

There are several ways in which MM management may intersect with prevention. Primary prevention strategies such as colorectal cancer (CRC) screening may be most appropriate for those with mild or no symptoms and secondary prevention strategies such as diagnostic screenings through colonoscopy may be most appropriate for those with significant chronic conditions. The demands of MM management may overshadow prevention activities, decreasing the likelihood that prevention will be addressed (Crabtree et al., 2005; Summerskill & Pope, 2002). Treatment, monitoring, and counseling demands of multiple conditions may exceed the available visit time, leaving little time for discussion of disease prevention (Piette & Kerr, 2006; Yarnall, Pollak, Ostbye, Krause, & Michener, 2003). Stange, Woolf, and Gjeltema (2002) indicated that patients coming in for “well care” receive on average 1.4 min dedicated to health promotion, but those coming in for chronic conditions spend, on average, only 0.8 min.

Most research suggests inverse relationships between MM and health care providers’ advocacy for and patients’ receipt of preventive services. One study of patients with diabetes found that patients with greater levels of comorbidity received fewer blood glucose tests (Halanych et al., 2007). Another study found that 58% of older women in poor health, who presumably are more likely to have MM, compared with 71% in better health had a recent pap smear (Mandelblatt et al., 1999). Yet another study found that for each unit of increase in a comorbidity index, there was a 17% decrease in the likelihood of mammography, a 13% decrease in clinical breast exams, and a 20% decrease in pap smears (Kiefe, Funkhouser, Fouad, & May, 1998). This is consistent with the finding that with increasing MM, physicians are less likely to request mammograms and women are less likely to receive breast and cervical screening (Schoen, Marcus, & Braham, 1994).

Despite the many challenges MM can create for prevention, some researchers have argued that as individuals with MM are more involved with the health care system, they have more opportunity for engagement in disease prevention activities. For example, patients aged 65 and above with fewer than six conditions have an average of 2.1 primary care visits and 1.8 specialist visits a year, whereas patients with six to nine conditions have 3.9 primary care and 4.3 specialist visits (Starfield, Lemke, Herbert, Pavlovich, & Anderson, 2005).

As patients receive preventive services during 39% of chronic disease management appointments to family physicians visits, those making more frequent visits might reap the benefits of additional prevention counseling (Stange, Flocke, & Goodwin, 1998). Similarly, research shows that diabetics with five or more chronic conditions are 67% more likely to receive a hemoglobin A1C test and 50% more likely to receive eye exams compared with diabetic patients with no additional chronic conditions; these higher rates of preventive care are related to the greater number of office visits (Bae & Rosenthal, 2008). Fleming, Pursley, Newman, Pavlov, and Chen (2005) proposed that this “surveillance hypothesis” might explain why conditions such as cardiovascular disease seem to be related to decreased odds of late-stage breast cancer, presumably due to increased screening and early detection. Alternately, Min and colleagues (2007) found that greater numbers of chronic conditions were associated with higher quality of care, speculating that physicians provide more rigorous attention to their more complex patients. While Min et al. examined quality of care indicators, rather than prevention specifically, their findings support the possibility that MM may actually facilitate disease prevention activities.

Rural Residents, MM, and Prevention

Rural residents are not only more likely to have MM but also to experience MM within a resource scarce context (Rowland & Lyons, 1989). Many rural areas in general, and rural Appalachia specifically, lack sufficient health care personnel and have greater distances to health services than nonrural areas, factors that may delay or prevent health care (Hutson, Dorgan, Phillips, & Behringer, 2007; Ricketts, 2000). Rural residents also are more likely than nonrural residents to lack vital resources like health insurance and transportation and to have greater socioeconomic disadvantage (Yabroff et al., 2005). Rural Appalachia also has greater economic distress and lower educational attainment, factors associated with poorer health outcomes (Behringer & Friedell, 2006; Bostick, Sprafka, Virnig, & Potter, 1994; Litaker & Tomolo, 2007).

Many of these same factors that contribute to increased rates of MM in rural areas also obstruct preventive care. Researchers have found that rural residents are less likely than urban residents to obtain various preventive health services (Bryant & Mah, 1992; Casey, Thiede Call, & Klingner, 2001; Coughlin & Thompson, 2004). Rural residents are less likely to get mammograms, pap smears, and colon cancer screening than their urban counterparts, likely reflecting environmental, systemic, and personal resource constraints (Casey et al., 2001).

Several potential explanations have been offered for the lower rates of preventive care in rural areas. Residents of rural Appalachia have been said to have a strong sense of privacy, a value of self-reliance, and some distrust of health professionals, making medical visits or certain screening practices seem unnecessary, embarrassing, and undesirable (Behringer et al., 2007; Goins, Williams, Carter, Spencer, & Solovieva, 2005). Rural residents may be more likely than urban residents to view cost as a barrier, especially if screening is to prevent an asymptomatic condition (Blazer, Landerman, Fillenbaum, & Horner, 1995). Competing life demands or priorities such as work or providing for children often make “fixing something that isn’t broken” especially unpalatable (Blazer et al., 1995). In addition, many residents of rural Appalachia are underinsured or uninsured and may choose disease uncertainty over costly out-of-pocket screening costs (Hutson et al., 2007). For their part, health care providers in rural Appalachia have identified barriers to recommending cancer screening for their patients, including time constraints, scheduling challenges, conflicting guidelines, and the belief that their patients would be reluctant to engage in screening due to undervaluing prevention (Shell & Tudiver, 2004).

Given the challenges of managing MM in general and the added difficulties involved in managing MM within a rural environment, this study examines how rural Appalachia residents with MM balance disease management and primary prevention, specifically CRC screening.

Specifically, we sought to describe participants’ perspectives on the challenges of managing MM and engaging in CRC preventive care within their rural context and explanations for how having multiple chronic conditions shapes preventive care. In this first portion of three complementary and sequential research activities, we employed an ethnographic approach (characterized by holism, obtaining insights from several sources, development of descriptive data, and creation of field notes) to expand our limited understanding of the relationship between MM and CRC prevention.

Method

Sample Eligibility and Recruitment Procedures

Forty-one participants were recruited from three family and community medicine practices in Appalachian Kentucky. Eligibility criteria included patients aged between 50 and 76 with multiple chronic conditions. Consistent with the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), we conceptualized “chronic conditions” as any illness that lasts for at least 3 months (NCHS, 1987). As there is no agreed on list of chronic conditions, we developed a comprehensive roster from four sources: Charlson (Charlson, Pompei, Ales, & MacKenzie, 1987), Elixhauser (Elixhauser, Steiner, Harris, & Coffey, 1998), the National Health Interview Survey (Pleis, Lucas, & Ward, 2009), and our own work (Fleming et al., 2005). The chronic disease list was then examined by our project physician-scientist for completeness. Given the focus on CRC screening, participants were excluded if the clinic physician considered them to be too vulnerable for CRC screening or if they had colostomy, Crohn’s Disease, iron deficiency anemia, ulcerative colitis, rectal bleeding, lower abdominal pain, irritable bowel syndrome, or a recent CRC diagnosis. The medical practices were selected on the basis of their willingness to engage in this research, their patient base (i.e., served a general population rather than being a specialty clinic, for example, pediatrics), and their location in counties with fairly representative characteristics for rural underserved populations (e.g., provider shortages, socioeconomic status, and health indicators similar to other Appalachian counties).

On selection of each practice, clinical staff compiled a list of up to 100 patients aged between 50 and 76 years who had visited the clinic within the past year. The provider proceeded to scan through the list and circle those who would be eligible for our study (by virtue of MM status). Providers then mailed a letter of invitation on practice letterhead, with a self-addressed stamped envelope and a telephone number. The letter requested that the potential participant mail back the letter or call our office if he or she was interested in participating in the project. On receipt of the letter or the telephone call, our local interviewer verified their eligibility status, explained the project procedure, and—if appropriate—set up an interview appointment. All protocols were approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board.

Interview Procedure

Informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the first interview. Participants engaged in two in-depth interviews, each with open-ended, semistructured, and structured questionnaires and each lasting 60 to 90 min. Two interviews were needed to cover the substantial number of questions relevant to the topic without overburdening participants, many of whom are severely ill. The interviews took place at a mutually agreeable location, usually at the participant’s home. Participants were asked about their health behaviors, health beliefs, health status, the time and resources involved in managing their chronic conditions, and their doctors’ visits and preventive care activities. In addition to asking specifically about CRC screening, we asked people to discuss prevention activities, thus encouraging participants to frame such activities on their own terms. All participants also completed a sociodemographic questionnaire at the end of the first interview.

To better understand Appalachian residents’ perspectives on disease management and CRC prevention, we assessed whether they undergo CRC screening. This was assessed using a question from the sociodemographic questionnaire, “When did you have your last CRC screening test?” In addition, transcripts were used to identify and quantify the type of screening (i.e., modality) a participant had, and whether the participant was in compliance with professional recommendations for CRC screening. To assess compliance with CRC screening guidelines, we compared the last screening date and modality to the recommended screening frequency for that modality. For example, if a participant indicated he or she underwent fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) 9 months ago, we considered this within the guidelines, but if he or she indicated FOBT 18 months ago, this would be coded as out of compliance. The consulting physician on the project reviewed all cases and made compliance assessments in accordance with CRC screening guidelines from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2008).

To preempt literacy concerns, all questions were read to the participant and all interviews were audiotaped. The second interview took place within 1 month of the initial interview. Participants received US$25 for the first interview and US$35 for the second interview.

Study Location

In Kentucky, the rates of chronic diseases are among the highest in the nation, with the 54 counties of Appalachian Kentucky exceeding state prevalence rates for many conditions. Kentucky ranks 48th for cardiovascular disease, 45th for stroke, 44th for obesity, and 41st for diabetes (United Health Foundation, 2009). Cancer rates are also among the highest in the nation; in Appalachian Kentucky, the all-cancer mortality rate is 17% higher than the U.S. rate. For CRC, the Appalachian Kentucky rate is about 11% higher than the national average, resulting in Kentucky experiencing the second-highest death rate from CRC in the United States.

This study was conducted in four counties in rural Appalachia. As Table 1 indicates, socioeconomic and health indicators of this region are among the lowest in the United States. Within the counties, socioeconomic indicators were similarly low (with the exception of one county with a low unemployment rate), with higher poverty rates and lower educational attainment than the entire Appalachian region.

Table 1.

Selected Socioeconomic Indicators: United States, Kentucky, and Appalachian Kentucky

| Per capita income (2002) | Poverty rate (2000) (%) | Unemployment rate (2003) (%) | High school diploma ages 25+ (2000) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | US$30,906 | 12.4 | 6.0 | 80.4 |

| Kentucky | US$25,494 | 15.8 | 6.2 | 74.1 |

| Appalachian | US$19,467 | 24.4 | 7.4 | 62.5 |

| Kentucky | ||||

| Breathitt County | US$17,559 | 33.2 | 10.6 | 57.5 |

| Floyd County | US$19,568 | 30.3 | 8.0 | 61.3 |

| Knott County | US$17,047 | 31.1 | 4.9 | 58.7 |

| Perry County | US$20,926 | 29.1 | 8.4 | 58.3 |

Source: Appalachian Regional Commission http://www.arc.gov/index.do?nodeID=56#Query1

Although with this suboptimal health profile we could have selected any preventive health behavior, we choose to focus on MM in the context of CRC screening because there is a fairly strong medical consensus on CRC screening (for most patients, FOBT annually, or once every 5 years for flexible sigmoidoscopy, or once every 10 years for colonoscopy; Winawer et al., 1997) and because the behavior is relatively uncomplicated. Unlike, for example, smoking cessation or energy balance, cancer screenings are relatively straightforward and not lifestyle changing. Thus, using CRC screening as an exemplar allows us to better understand fundamental ways in which MM intersect with prevention health behaviors. As a qualitative, exploratory study, our intention was not to determine the relationship, let along causality, among MM and its management, CRC screening, and sociodemographic characteristics but was rather to provide informants’ accounts of the intersection between their diagnosed conditions and a preventive health behavior, CRC screening.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using conventional content analysis, a broad range of approaches that vary from intuitive and interpretative analyses to textual procedures (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). As Downe-Wamboldt (1992) noted, similar to many other types of qualitative analysis, the goal of content analysis is to “provide knowledge and understanding of the phenomenon under study,” extending beyond categorization of textual data and is not limited to more traditional perceptions of words (p. 314). Consistent with Hsieh and Shannon (2005), we use qualitative content analysis as a “research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns” (p. 1278). We selected this approach because of our intention to describe rural residents’ experiences with MM and cancer prevention, a topic that has yet to be explored and warrants the development of inductive categorical (Kondracki & Wellman, 2002).

On completion of each interview, each session was professionally transcribed, checked for accuracy, and reviewed to identify emergent themes and ensure that any missing line of inquiry was represented in subsequent interviews (Crabtree & Miller, 1999). We repeatedly read each of the transcripts, immersing ourselves in the transcripts to achieve a broad-based understanding of the content. Then, we derived codes by reading transcripts line-by-line, developing impressions and initial thematic insights. Initial codes give way to more expansive codes that become sorted into categories that are useful grouping devices (Patton, 2002). We compiled these codes and emergent categories into a codebook. New codes were added and the codebook was refined as new codes emerged. Following the traditions of Willms et al. (1990) and Miles and Huberman (1994), immersion into existing literature on chronic disease management and prevention led us to anticipate some overall themes and sub-themes; however, we used no preexisting analytic templates and remained in “discovery mode” (Bernard, 2002, p. 465).

Coding outcomes were periodically compared among the research team to ensure consistency, and discrepancies were addressed by further modifying the codebook and recoding the transcripts. This iterative process of coding, comparing codes, clarifying instances of discrepant codes, and recoding was repeated until we ultimately established an intercoder reliability ratio of approximately 80%, generally considered to be a satisfactory level of agreement (Bernard, 2002). We used the qualitative software package NVivo to improve data organization and management. Consistent with other qualitative content analytic approaches, relevant theoretical frameworks tend to be integrated in a discussion section rather than initiating the study with preconceived categories (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Results

Sample Characteristics

As shown in Table 2, the vast majority of the participants had low income, were unemployed, and had relatively modest education. The majority of the participants had Medicare or Medicaid; only a small minority had no health insurance. The majority perceived their health as poor or fair; the most commonly reported conditions were high blood pressure, arthritis, high cholesterol, heart disease, and diabetes, with participants on average having 4.7 conditions.

Table 2.

Sample Description

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (range) | 63 (51–77) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 41 | 100.0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 12 | 29.3 |

| Female | 29 | 70.7 |

| Health status | ||

| Poor | 11 | 26.8 |

| Fair | 11 | 26.8 |

| Good | 9 | 22.0 |

| Very good | 9 | 22.0 |

| Excellent | 1 | 2.4 |

| Health conditions | ||

| High blood pressure | 31 | 75.6 |

| Arthritis | 28 | 68.3 |

| High cholesterol | 20 | 48.8 |

| Heart disease | 15 | 36.6 |

| Diabetes | 12 | 29.3 |

| Stroke | 4 | 9.8 |

| Cancers | 7 | 17.1 |

| Sleep apnea | 5 | 12.2 |

| Other | 39 | 95.1 |

| Mean number of health conditions (range) | 4.68 (2–10) | |

| Current marital status | ||

| Never married | 3 | 7.3 |

| Divorced | 3 | 7.3 |

| Widowed | 4 | 9.8 |

| Married | 30 | 73.2 |

| Separated | 1 | 2.4 |

| Education | ||

| <High school | 11 | 26.8 |

| =High school | 20 | 48.8 |

| >High school | 10 | 24.4 |

| Income | ||

| <US$25,000 | 20 | 48.8 |

| US$25,000–US$50,000 | 12 | 29.3 |

| >US$50,000 | 9 | 22.0 |

| Current financial status, self-assessed | ||

| Struggle | 15 | 36.6 |

| Enough to get by | 17 | 41.5 |

| More than enough | 9 | 22.0 |

| Insurance type | ||

| None | 4 | 10.0 |

| Medicaid | 7 | 17.5 |

| Medicare | 5 | 12.5 |

| Employer-sponsored | 4 | 10.0 |

| Private | 8 | 20.0 |

| Dual eligible | 12 | 30.0 |

| Mean years of living in current county (range) | 50.16 (8–76) | |

| Work status/currently working | ||

| No | 34 | 82.9 |

| Yes | 7 | 17.1 |

Note: N = 41.

Table 3 provides information on CRC screening, including reported adherence and modalities. Nearly half (44%) of the participants had their last CRC test within the past 2 years, whereas nearly one third (32%) indicated that they had experienced a CRC screening test more than 2 years ago. Nearly a quarter (24%) of our sample could not recall if and when they had their last CRC screening test. Of the participants who could recall their last screening test, the following screening modalities were reported: (a) colonoscopy, including virtual colonoscopy (48%); (b) FOBT (13%); and (c) digital rectal examination (3%). Just over a third (36%) did not recall the modality. Comparing the self-reports of time since last screening and modality of screening with the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2008) recommendations, we determined that 16 participants (39%) received a particular screening test in accordance with medical guidelines.

Table 3.

CRC Screening Information

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Last CRC screening test, years ago | ||

| Cannot recall | 10 | 24.4 |

| >2 years | 13 | 31.7 |

| 1–2 years | 6 | 14.6 |

| ≤ 1 year | 12 | 29.3 |

| Adherent to CRC screening guidelines | ||

| No | 25 | 61.0 |

| Yes | 16 | 39.0 |

| CRC screening modality (of those who could recall last screening test) | ||

| Colonoscopy | 15 | 48.4 |

| FOBT | 4 | 12.9 |

| Digital rectal exam | 1 | 3.2 |

| Modality not specified | 11 | 35.5 |

Note: CRC= colorectal cancer; FOBT = fecal occult blood testing. N = 41.

Rural Environment Creates Preventive Care Challenges

Several features unique to rural, and more specifically Appalachian, communities make it difficult for those with MM to pursue CRC screening. These features include (a) a sense of isolation, (b) insufficient community and financial resources, (c) limited prevention awareness, and (d) attitudinal factors.

Although participants were not all explicitly asked about the role of rurality in their screening practices, many directly identified their community environment as a challenge to CRC screening. Perceived isolation—including transportation and access to care—is frequently discussed as obstructing CRC prevention. Mr. L., 72 years old, cites transportation and other access issues to explain why people in his community might not get cancer screening:

If you live in a hollow, you are going to have problems that people in town never face. As far as having transportation or access to a library and support group, church group, they [those living in hollows] are just isolated.

Provider availability is also discussed as a barrier to both MM management and CRC prevention. Many participants are frustrated by a lack of choice or options between doctors and trouble scheduling appointments due to high patient volume and demand. Mrs. M., who is 58 years old, discusses how everyone in her county has to travel to another county to have a colonoscopy as her county lacks appropriate medical facilities. Mrs. R., aged 54, discusses being happy with her doctor but also finds it difficult to get an appointment:

Dr. Z. and his office is totally backed up. If you want an appointment you’re looking at 3 months, 2 months at the minimum to get in to get an appointment. People get discouraged from that. I know that when we were going with my husband’s test and so forth, we were having to wait a month, 2 months to get an appointment, even when we knew something was wrong and it needed to be followed up on. There’s people coming out the door so you know you have to wait and there’s nobody else to go to. It’s not that he’s not a good doctor. You know it’s not anything like that. It’s just that people get discouraged when they have to wait too long, and they just give up and don’t fool with it.

Limited personal finances and inadequate or absent health insurance also obstruct preventive care. Although such constraints are not uncommon elsewhere, Appalachian residents with MM frequently experience uninsurance or underinsurance and lack resources for out-of-pocket expenditures. Fifty-two-year-old Mrs. P., who has arthritis, high blood pressure, diabetes, and other chronic conditions, discusses how between doctors visits and medications the costs of managing her MM add up, leaving her with few financial resources to pursue anything but disease containment:

Well I have to go to Dr. after Dr., and I have co-pays every time I go, and I’m on a fixed income. Two dollars, three dollars that don’t sound like much, but once you start having to pay it and you don’t have it then you feel the pinch. And it’s just so tiresome having to go to all those doctors. Every time you go to one of them, they will send you to another doctor. I must have 10 doctors that I go to. I have 18 or 20 different medicines that I have to take. I have to pay a dollar to two dollars to three dollars depending, generics is a dollar, name brand is two dollars, and there are certain medications there that they have to have approval to cover and most of those will cost three dollars. When you are taking 20 bottles of medicine, and you have anywhere from 24 to 30 dollars to pay, on top of all them doctors you just had to pay for, it’s hard. If you go to one doctor to the next, they will change everything you are on, even though you are doing fine on the medications that you are on because they want you on their medications. Just like, I changed doctors the first of this month and when I go see this new doctor they will probably change a lot of my medications.

Given the economic disadvantage of this population, limited resources lead residents to deprioritize all but the most essential costs. Fifty-one-year-old Mrs. E. indicates that managing MM is costly and that if insurance does not cover the entire screening procedure, she will not pursue it. She explains that if asked to pay for the procedure,

That [paying] might be something that would make it harder for them [people with MM] to do this [screening] because this is not something that may be imminent—it’s not like arthritis that is telling you that you have to take care of it right then, so they may be putting it on a back burner.

Many residents mention a lack of community awareness of the importance of cancer prevention. Fifty-seven-year-old Mrs. Y. indicates that prevention may be less likely “in a community where health issues are not addressed or encouraged or where local health agencies don’t take an active part in the community about education.” Others talk about how people are not informed about the need for screening and do not view themselves as at risk. Mrs. S., age 58, says, “They just don’t figure that it will ever happen to them and they are too bothered with other things. They just coast through life most of the time or fly through it if they’ve got a lot of commitments.” Mr. L. discusses how a lack of awareness of the need for cancer screening thwarts prevention:

I think that our people, they don’t get the preventive care that they need, not because the resources are not out there but because number one they don’t know about them. And if they do know about them, they don’t see the gravity of the need to go for these resources. So they wait until the ultimate happens, till a problem occurs that could have been prevented, and then they try to go to the doctor … Our people are dying for lack of knowledge.

Participants discuss how limited knowledge and awareness relate to the local context. Fifty-four-year-old Mrs. R. speaks about how her community is disconnected from prevention messages: “In this kind of area where it is so closed off, the outside world doesn’t invade as much; the information highway is not so available.” In addition to perceived isolation, inadequate resources, and limited prevention awareness, some participants describe the role that attitudinal factors play in prevention orientation. Sixty-one-year-old Mrs. C. indicates how concerns about privacy and embarrassment may limit CRC screening: “I think people here in Eastern Kentucky are just private people, and to them, a colonoscopy is an embarrassing procedure. Unless they have problems, they will not get the test for that reason.”

Prevention is a Secondary Priority

Many participants discuss how CRC prevention is a secondary concern to MM management, particularly in explaining the motivation for and content of doctors visits. Many participants state that they only go to the doctor when they feel bad and that their visits tend to be guided by immediate problems and existing health conditions. While participants discuss visits occasionally incorporating prevention, discussion of prevention is often incongruent with the participant’s own goals and consequently doctors’ efforts to incorporate prevention are often rejected.

Mrs. S. who has arthritis, heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, Ménière’s Disease, and several other health problems explains the lack of a preventive focus in her doctors’ visits: “I pretty much do what the doctor suggests, and all of them are so busy dealing with what’s already wrong that it’s hard to focus on preventing something.” Similarly, 68-year-old Mrs. B. who has diabetes, arthritis, high cholesterol, and thyroid disease talks about cancer prevention and says, “I’ve never been screened that much for cancer … They’re in the diabetic mood every time I go to the doctor.” Mrs. G. who has arthritis, hypothyroidism, and high cholesterol discusses how her doctors get “caught up in acute care and they don’t value health promotion/disease prevention highly enough to incorporate it into the way they manage their practice.” She explains her concern with this omission of prevention:

People get caught up in making sure that their medications have been reordered and that various other tests and procedures that are connected to their chronic care get done. It’s sort of like fighting fires. You fight fires, and you fight fires, and you’re not necessarily looking over your shoulder to see the approaching flood. It’s ironic because I think the United States has created a health care system that has functioned that way, and we don’t have to. There are a lot of other nations that do it differently; they focus on health promotion and disease prevention so that they cut down the acute care on the other end. But we do it backwards in our health care nation. We have taught patients to do it backward, and if a patient isn’t educated otherwise, you can’t tell someone what you don’t know or what you never heard, so they don’t ask questions of their physicians, they don’t offer information that might cue a physician to test or look for a problem earlier.

Disease Management is Exhausting

Participants also discuss how time demands from existing conditions leave little energy or resources for CRC screening. Various factors contribute to the perception that MM consume significant amounts of time: (a) the thought and worry that goes into the condition; (b) the self-care requirements; (c) the limitations, symptoms, and physical disabilities resulting from the conditions; and (d) the time spent traveling, waiting for, and meeting with doctors.

For many participants, some combination of the above factors diminishes their internal resources. Mrs. A., aged 70, describes how

For the last 3 years I have went through just about every test that they have got to find out what was wrong with me, and I just worn down until I am tired. I’m tired of going to the doctor. I’m tired of doing what the doctor says … I just want to rest and then I will go and have some more [preventive] things done later.

For Mrs. P., managing her MM seems to consume all of her time, leaving her little desire or room for cancer screenings:

I’ve had to have too much stuff done to me in my life. It’s hard for me to agree to have other tests and other procedures done because I’ve about five or six surgeries. I constantly have to go to the doctor. I have so many appointments that that is my life, going to the doctor. And every time I go see one doctor, they add two or three more doctors to me. I’m ready to quit the whole thing and just say, “fooey with you all.” I’m ready to go home and have a life of my own. I mean, I can’t get to do nothing with my family or anything. I’ve got family that wants me to come and visit them in Indiana and stuff, but how can I go if I got those appointments?

For some participants, managing all their conditions is not only exhausting but also emotionally taxing. Mrs. D., aged 64, who has arthritis, heart disease, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, and kidney disease, discusses her response to the constant medical requirements of her MM:

It’s hard, it’s very hard. By the time I work all my appointments in, you don’t feel like doing anything else trying to get all that done. By the time you go to each doctor, and each tells you what is actually wrong, and they do tell you, then you come home, then there’s not much. I don’t know I just get really depressed with it, very depressed.

Similarly, Mrs. G. mentions how disease management can be trying both physically and mentally, making preventive activities such as CRC screening less likely:

With a lot of chronic diseases, a lot of people just have limited energy, and they sometimes suffer from depression, and they’re just not in a frame of mind to do what they consider less than necessary types of procedures. And, they just don’t have the awareness of how necessary health promotion and disease prevention is and why.

MM has a Direct Impact on Prevention

Participants note that MM directly impacts preparation for CRC screening procedures (making preparation challenging or particularly unpleasant), contributes to physical limitations which decrease screening ability, and increases concerns about sedation. Fifty-three-year-old Mr. F., who has heart disease, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, and a history of stroke and seizures, describes how diabetes makes colonoscopy preparation particularly challenging:

Having to drink the goo, especially if you have diabetes. You get weak and you have to drink two gallons of the nasty stuff. You can’t eat because you have to get your system clean before the test, and when you are a diabetic your sugar bottoms out easy when you don’t eat.

Mrs. J., aged 56, has arthritis, heart disease, high blood pressure, sleep apnea, and high cholesterol and speaks about how physical limitations may decrease a provider’s likelihood of recommending screening:

If you have something, a lot wrong with you, they may think “well ain’t no use trying that.” You know, she’s or he’s not physically able to go through the testing, sometimes that happens, and other times it just could be what’s wrong with you, you know that they couldn’t do it.

However, several participants discuss how MM may actually facilitate CRC screenings. Explanations were provided for this relationship—screening procedures were integrated into disease management procedures, other conditions prompted the individual to purchase insurance which then made prevention activities more economically feasible, and having MM increased contact with the doctor and therefore increased the opportunity for prevention. Mrs. R. explains how she believes more conditions will lead to greater patient-doctor interaction and therefore increase the likelihood of screening:

Most of time if you have those conditions, you are going to the doctor anyway. And those doctors will recommend you follow up on certain things that are set for screening at certain ages. At certain ages, you should start being screened for a mammogram, at a certain age you should start being screened for CRC. I think they are going to mention that in your routine visits. I think that would probably increase the likelihood that you would have one [cancer screening] done instead of decrease it.

Discussion

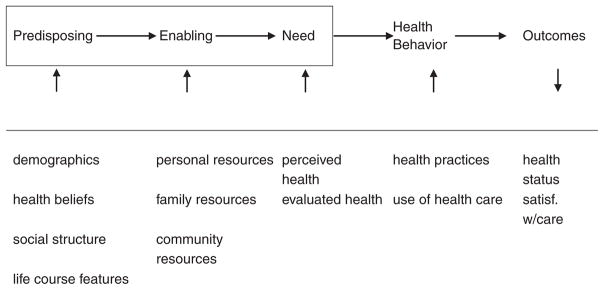

This study presents a first look into how vulnerable populations facing multiple health, financial, and environmental challenges think about and engage in CRC prevention. The themes identified in this study are consistent with the framework provided by the modified behavioral model for vulnerable populations (BMVP; Gelberg, Andersen, & Leake, 2000). The BMVP focuses on the role of predisposing variables (e.g., demographic variables and health beliefs), enabling variables (e.g., personal, family, and community resources), and need factors (e.g., perceived and evaluated health) in predicting health behavior, in this case CRC screening behavior, and outcomes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Modified behavioral model for vulnerable populations

Source: Gelberg, Andersen, and Leake (2000).

Note: MM = multiple morbidity; CRC = colorectal cancer; BMVP = behavioral model for vulnerable populations. The original model has been modified to better reflect the health concerns (MM and CRC screening) of interest. Gelberg et al.’s original BMVP focused on homeless populations that experience a different type and scale of vulnerability. Thus, instead of including childhood characteristics like criminal behavior and prison history, life course circumstances like length of time in community and community resources have been included. The overall domains, however, are very similar.

Participants in this study discuss the role of predisposing factors, including the belief that prevention is a secondary concern relative to disease management—both in terms of scheduling visits and in the content of those visits. Participants also discuss how enabling factors, particularly limited personal and community resources and competing disease demands, make prevention more challenging. Such resource limitations include impeded access to formal care, including provider shortages resulting in scheduling difficulties and long waits in the office; limited financial resources, which are exacerbated by insufficient health insurance; and limited knowledge and awareness of preventive health recommendations, all of which decrease the likelihood of obtaining CRC screening. Finally, participants discuss how need factors, including their multiple chronic conditions, influence their CRC prevention activities. Participants emphasize how managing MM is time intensive and exhausting, diminishing their energy and perceived time available for prevention. Furthermore, participants’ MM may make actual screening preparations or procedures more difficult, though a few participants believe MM increases the likelihood of prevention by creating opportunities for prevention to be incorporated into management procedures or visits.

Limitations

This study focuses specifically on CRC screening, and thus it is unclear the extent to which these findings can be generalized to other prevention activities. Generally, CRC screening is considered a form of secondary prevention; individuals with MM may have very different experiences with other types of secondary prevention and with primary prevention, such as dietary improvement, and tertiary prevention, such as monitoring medications. In addition, the study’s small sample size and narrowly defined geographic area may limit the generalizability of our findings. However, many of the BMVP components—predisposing, enabling, and need factors—discussed among this vulnerable, rural population are likely to play a similar role in other prevention contexts and likely will apply to other traditionally underserved populations. Another limitation of the present study is the reliance on self-report for CRC screening information. Previous research has shown an optimistic bias in self-report (Adams, Soumerai, Lomas, & Ross-Degnan, 1999; Gordon, Hiatt, & Lampert, 1993); thus, it is possible that preventive care data, in particular adherence to CRC screening recommendations, may be lower than reported. However, if this were the case, the findings would be of even greater alarm. Reliance on patient’s recollection also creates the potential for imprecision regarding time since a screening procedure. Of additional concern, and discussed below, is participants’ lack of clarity on CRC screening modality, even when they have had such tests. Adherence to CRC screening guidelines should also be considered with caution because participants were often unsure about the type of screening received.

Implications and Recommendations

This study highlights barriers to CRC screening in the context of MM among rural residents. Although, in general, pursuing cancer screening is considered a health promoting activity, it is important to keep in mind that CRC screening may not be universally appropriate for all individuals aged 50 to 76 with MM. As Walter and Covinsky (2001) discussed, cancer screening decisions should not be guided solely by age, rather, risks, benefits, and patient preferences should all play a role in assessing appropriateness of screening. It is possible that given the disease profiles among some of the individuals in this sample, anticipated life expectancy may not have been extensive enough to warrant the discomforts and potential risks of screening. Alternately, while the quantitative risk-benefit relationship may favor screening, individuals may feel that their quality of life is not high enough to pursue prevention efforts that would require additional treatment. When these factors are carefully evaluated, the decision not to screen may be appropriate. However, even if the considerations suggested by Walter and Covinsky were incorporated into clinical decision making, secondary prevention through screening would still be recommended for many individuals with MM between ages 50 and 76. Thus, it remains important to consider how to make this rural, resource-challenged environment more conducive to CRC screening.

While some participants’ perspectives may be unique to individuals in rural, underresourced areas, such as a sense of isolation, many of the factors shaping the MM experience and CRC screening would be applicable to most middle-aged and older adults. However, the contextual challenges of a rural underresourced area may exacerbate the prominence of some factors. For instance, with fewer personal and community resources, prevention may be more likely to recede in importance relative to other health and life concerns. Similarly, limited resources may also make disease management seem more demanding.

Recognizing the importance of these various factors, this study suggests several approaches that might reduce the significant barriers to CRC prevention faced by rural residents with MM. Several of our participants indicated a lack of awareness between flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy, two very distinctive screening modalities, whereas others were unsure which CRC screener they had experienced. As CRC screening tests are among the latest to become a standard of cancer prevention, vigorous campaigns must be launched to increase understanding and awareness of CRC screening modalities.

The lack of prevention awareness may be the most easily remedied. As receiving a physician’s recommendation is among the most persuasive factors in the uptake of preventive health activities (Post et al., 2008; Shokar, Nguyen-Oghalai, & Wu, 2009), it is essential that providers discuss this recommendation with their patients, taking into account patients’ educational background and financial situation as well as their complex medical history and diagnoses.

However, increased awareness and receiving providers’ recommendations may not be sufficient to increase screening behavior. Accordingly, many health organizations are experimenting with lay health advisers or patient navigators, to help patients overcome barriers to treatment. Acknowledging that rural providers face time constraints, creative approaches, including the use of paraprofessional staff members—trained individuals who are not licensed but support professionals, who could provide additional prevention consultation services at a low cost—might be helpful. Like certified diabetes educators, these paraprofessionals could consult with patients as they are waiting to be seen by the physician or immediately on exiting the examination room. Such paraprofessional approaches have been successfully used to encourage preventive health activities such as cancer screenings (Brownstein, Cheal, Ackermann, Bassford, & Campos-Outcalt, 1992; Levy-Storms & Wallace, 2003). However, given the greater priority that most patients place on their chronic conditions, paraprofessionals and providers must be sure to discuss prevention in the context of MM. It is also important that they be sensitive to the fact that while the state of having MM may remain constant, the experience of MM varies; symptoms can fluctuate and patient receptivity to CRC screening may differ between visits.

Another approach to increase preventive care among those with MM is to implement the Chronic Care Model (CCM). The CCM contains six elements to enhance chronic disease management and support prevention: (a) community resources and policies, (b) healthy system organization of care, (c) self-management support, (d) delivery system design, (e) decision support, and (f) clinical information systems (Glasgow, Orleans, & Wagner, 2001). The CCM has been successful in rural areas for management of chronic conditions. One study focusing on diabetes patients in a rural setting found that implementing elements of the CCM, including decision support, self-management, and delivery system redesign, resulted in improvements in the care provided and patient outcomes (Siminerio, Piatt, & Zgibor, 2005). A review of studies using the CCM demonstrated that the vast majority resulted in improvements in patient outcomes and that two thirds also resulted in cost savings (Bodenheimer, Wagner, & Grumbach, 2002). It has been proposed that the CCM be expanded to include community and social determinants of health to increase prevention (Barr et al., 2003). Applications of the CCM principles to promote prevention seem promising (Glasgow et al., 2001).

In particular, this study highlights the importance of community resources, one of the elements of the CCM, to support prevention. In the absence of the optimal situation of increasing medical resources in rural areas, creative approaches must be sought to address health care provider shortages, transportation limitations, and uninsurance or underinsurance. One possible approach would be to centralize care, making the primary care visit more comprehensive. If the primary care provider or paraprofessional took care of both disease management and prevention activities, many of the barriers to preventive screening would be minimized. In addition, if resource (both personal and community) considerations constitute the main barriers to colonoscopy for people with MM, in rural areas FOBT may be a preferable, lower-tech, more accessible option than no screening at all.

Balancing disease management of MM and disease prevention within an underresourced environment presents a number of challenges. Incorporating preventive care within disease management visits may help facilitate prevention, which also alleviates disease management burdens in the long run. Stange et al. (2002) suggested a goal of “one minute of prevention” in doctor’s visits, increasing prevention awareness and activities by incorporating them into disease visits. This could be a valuable and feasible step to improving the health of rural residents with MM.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R21 CA129881).

Biographies

Shoshana H. Bardach, MA, is a gerontology PhD student in the Graduate Center for Gerontology at the University of Kentucky (UK). She earned her MA in psychology at Wesleyan University. She currently serves as a graduate research assistant in the College of Medicine, Department of Behavioral Science, and in the College of Health Sciences. Her main research interests include preventive health, positive aging, and clinical communication, with a focus on older adults with multiple morbidities.

Nancy E. Schoenberg, PhD, is the Marion Pearsall Professor in the College of Medicine, Department of Behavioral Science, Anthropology, and Internal Medicine. She is also a faculty affiliate in the Doctoral Program in Gerontology, the Department of Communication, and the Department of Health Behavior at the UK. She also serves as a president’s professor at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Much of her work involves understanding the complex constellation of factors underlying health decisions and, increasingly, administering community-based interventions to enhance health in traditionally underserved populations. Her ongoing research includes several projects for the NIH/National Cancer Institute on cancer in Appalachia related to screening, control, and cancer prevention involving faith communities. Additional projects involve an intergenerational energy balance intervention, a patient navigation project, and a study on multiple morbidities. She also serves as the associate editor for The Gerontologist.

Yelena N. Tarasenko, MPH, MPA, is a DrPH student majoring in epidemiology and health services management at the College of Public Health, UK. She is also a research assistant at the Department of Behavioral Science, UK.

Steven T. Fleming, PhD, is an associate professor in the College of Public Health, with appointments in both the Departments of Epidemiology and Health Services Management. He has master’s degrees in public administration (University of Hartford) and applied economics (University of Michigan), and a PhD in health services organization and policy from the University of Michigan. His research and publications focus on cancer epidemiology and health services research, in general, and the impact of comorbid illness on cancer diagnosis and treatment, in particular. He is the author of a textbook titled Managerial Epidemiology: Concepts and Cases (Health Administration Press, 2008).

Footnotes

Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Adams A, Soumerai S, Lomas J, Ross-Degnan D. Evidence of self-report bias in assessing adherence to guidelines. International Journal of Quality Health Care. 1999;11:187–192. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/11.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae S, Rosenthal M. Patients with multiple chronic conditions do not receive lower quality of preventive care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:1933–1939. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0784-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr VJ, Robinson S, Marin-Link B, Underhill L, Dotts A, Ravensdale D, et al. The expanded Chronic Care Model: An integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the Chronic Care Model. Healthcare Quarterly. 2003;7:73–82. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2003.16763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss EA, Steiner JF, Fernald DH, Crane LA, Main DS. Descriptions of barriers to self-care by persons with comorbid chronic diseases. Annals of Family Medicine. 2003;1:15–21. doi: 10.1370/afm.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behringer B, Friedell GH. Appalachia: Where place matters in health. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2006;3(4):A113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behringer B, Friedell GH, Dorgan KA, Hutson SP, Naney C, Phillips A, et al. Understanding the challenges of reducing cancer in Appalachia: Addressing a place-based health disparity population. Californian Journal of Health Promotion. 2007;5:40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology. Walnut Creek. CA: AltaMira Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG, Landerman LR, Fillenbaum G, Horner R. Health services access and use among older adults in North Carolina: Urban vs. rural residents. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:1384–1390. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.10.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: The Chronic Care Model, part 2. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:1909–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostick RM, Sprafka JM, Virnig BA, Potter JD. Predictors of cancer prevention attitudes and participation in cancer screening examinations. Preventive Medicine. 1994;23:816–826. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownstein JN, Cheal N, Ackermann SP, Bassford TL, Campos-Outcalt D. Breast and cervical cancer screening in minority populations: A model for using lay health educators. Journal of Cancer Education. 1992;7:321–326. doi: 10.1080/08858199209528189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant H, Mah Z. Breast cancer screening attitudes and behaviors of rural and urban women. Preventive Medicine. 1992;21:405–418. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90050-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey MM, Thiede Call K, Klingner JM. Are rural residents less likely to obtain recommended preventive healthcare services? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;21:182–188. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. Journal of Chronic Disease. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornoni-Huntley J, Foley D, Guralnik J. Co-morbidity analysis: A strategy for understanding mortality, disability and use of health care facilities of older people. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1991;20(Suppl 1):S8–S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SS, Thompson TD. Colorectal cancer screening practices among men and women in rural and nonrural areas of the United States, 1999. Journal of Rural Health. 2004;20:118–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree BF, Miller WL. In-depth interviewing. In: Miller W, editor. Doing qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. pp. 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Tallia AF, Cohen DJ, DiCicco-Bloom B, McIlvain HE, et al. Delivery of clinical preventive services in family medicine offices. Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3:430–435. doi: 10.1370/afm.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: Method, applications, and issues. Health Care for Women International. 1992;13:313–324. doi: 10.1080/07399339209516006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Medical Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming ST, Pursley HG, Newman B, Pavlov D, Chen K. Comorbidity as a predictor of stage of illness for patients with breast cancer. Medical Care. 2005;43:132–140. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200502000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, Vanasse A, Lapointe L. Prevalence of multimorbidity among adults seen in family practice. Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3:223–228. doi: 10.1370/afm.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: Application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Research. 2000;34:1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Orleans CT, Wagner EH. Does the Chronic Care Model serve also as a template for improving prevention? Milbank Quarterly. 2001;79:579–612. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goins RT, Williams KA, Carter MW, Spencer M, Solovieva T. Perceived barriers to health care access among rural older adults: A qualitative study. Journal of Rural Health. 2005;21:206–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon NP, Hiatt RA, Lampert DI. Concordance of self-reported data and medical record audit for six cancer screening procedures. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1993;85:566–570. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.7.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halanych JH, Safford MM, Keys WC, Person SD, Shikany JM, Kim YI, et al. Burden of comorbid medical conditions and quality of diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2999–3004. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson SP, Dorgan KA, Phillips AN, Behringer B. The mountains hold things in: The use of community research review work groups to address cancer disparities in Appalachia. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2007;34:1133–1139. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.1133-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerant AF, von Friederichs-Fitzwater MM, Moore M. Patients’ perceived barriers to active self-management of chronic conditions. Patient Education and Counseling. 2005;57:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz ML, Wewers ME, Single N, Paskett ED. Key informants’ perspectives prior to beginning a cervical cancer study in Ohio Appalachia. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17:131–141. doi: 10.1177/1049732306296507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefe CI, Funkhouser E, Fouad MN, May DS. Chronic disease as a barrier to breast and cervical cancer screening. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13:357–365. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondracki NL, Wellman NS. Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2002;34:224–230. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Storms L, Wallace SP. Use of mammography screening among older Samoan women in Los Angeles county: A diffusion network approach. Social Science Medicine. 2003;57:987–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00474-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litaker D, Tomolo A. Association of contextual factors and breast cancer screening: Finding new targets to promote early detection. Journal of Women’s Health. 2007;16:36–45. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelblatt JS, Gold K, O’Malley AS, Taylor K, Cagney K, Hopkins JS, et al. Breast and cervix cancer screening among multiethnic women: Role of age, health, and source of care. Preventive Medicine. 1999;28:418–425. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Min LC, Wenger NS, Fung C, Chang JT, Ganz DA, Higashi T, et al. Multimorbidity is associated with better quality of care among vulnerable elders. Medical Care. 2007;45:480–488. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318030fff9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey: United States, 1986. Vol. 3. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Department of Health and Human Services; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:725–731. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleis JR, Lucas JW, Ward BW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2008. Vital Health Statistics. 2009;10(242) Retrieved June 30, 2010, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_242.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post DM, Katz ML, Tatum C, Dickinson SL, Lemeshow S, Paskett ED. Determinants of colorectal cancer screening in primary care. Journal of Cancer Education. 2008;23:241–247. doi: 10.1080/08858190802189089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice DP, LaPlante MP. Medical expenditures for disability and disabling comorbidity. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82:739–741. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.5.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts TC. The changing nature of rural health care. Annual Review of Public Health. 2000;21:639–657. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland D, Lyons B. Triple jeopardy: Rural, poor, and uninsured. Health Services Research. 1989;23:975–1004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoen R, Marcus M, Braham R. Factors associated with the use of screening mammography in a primary care setting. Journal of Community Health. 1994;19:239–252. doi: 10.1007/BF02260384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberg NE, Kim H, Edwards W, Fleming ST. Burden of common multiple-morbidity constellations on out-of-pocket medical expenditures among older adults. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:423–437. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shell R, Tudiver F. Barriers to cancer screening by rural Appalachian primary care providers. Journal of Rural Health. 2004;20:368–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shokar NK, Nguyen-Oghalai T, Wu H. Factors associated with a physician’s recommendation for colorectal cancer screening in a diverse population. Family Medicine. 2009;41:427–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siminerio LM, Piatt G, Zgibor JC. Implementing the Chronic Care Model for improvements in diabetes care and education in a rural primary care practice. Diabetes Educator. 2005;31:225–234. doi: 10.1177/0145721705275325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange KC, Flocke SA, Goodwin MA. Opportunistic preventive services delivery. Are time limitations and patient satisfaction barriers? Journal of Family Practice. 1998;46:419–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange KC, Woolf SH, Gjeltema K. One minute for prevention: The power of leveraging to fulfill the promise of health behavior counseling. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22:320–323. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B, Lemke KW, Herbert R, Pavlovich WD, Anderson G. Comorbidity and the use of primary care and specialist care in the elderly. Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3:215–222. doi: 10.1370/afm.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerskill WS, Pope C. “I saw the panic rise in her eyes, and evidence-based medicine went out of the door.” An exploratory qualitative study of the barriers to secondary prevention in the management of coronary heart disease. Family Practice. 2002;19:605–610. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.6.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Health Foundation. America’s health rankings. 2009 Retrieved July 9, 2010 from http://www.americashealthrankings.org/yearcompare/2008/2009/KY.aspx.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. AHRQ Publication 08–05124-EF-3. 2008 Retrieved June 30, 2010, from http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/usp-stf08/colocancer/colors.htm.

- Van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JF, Roos S, Knottnerus JA. Multimorbidity in general practice: Prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51:367–375. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, Gibson TB, Marder WD, Weiss KB, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: Prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:391–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: A framework for individualized decision making. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:2750–2756. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willms DG, Best JA, Taylor DW, Gilbert JR, Wilson DMC, Lindsay EA, et al. A systematic approach for using qualitative methods in primary prevention research. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1990;4:391–409. [Google Scholar]

- Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, Godlee F, Stolar MH, Mulrow CD, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: Clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:594–642. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.agast970594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162:2269–2276. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, King JC, Mangan P, Washington KS, Yi B, et al. Mortality: What are the roles of risk factor prevalence, screening, and use of recommended treatment? Journal of Rural Health. 2005;21:149–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnall KSH, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: Is there enough time for prevention? American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:635–641. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]