Abstract

Background

Clinical research will increasingly play a core role in the evolution and growth of acute care surgery (ACS) program development across the country. What constitutes an efficient and effective clinical research infrastructure in the current fiscal and academic environment remains obscure. We sought to characterize the effects of implementation of a multidisciplinary acute care research organization (MACRO) at a busy tertiary referral university setting.

Methods

In 2008, to minimize redundancy, cost, and maximize existing resources promoting acute care research, MACRO was created unifying clinical research infrastructure between the Departments of Critical Care Medicine, Emergency Medicine and Surgery. Over the time periods 2008–2012 we performed a retrospective analysis and determined volume of clinical studies, patient enrollment for both observational (OBS) and interventional (INTV) trials, and staff growth since MACROs origination and characterized changes over time.

Results

From 2008 to 2011, the volume of patients enrolled in clinical studies which MACRO facilitates has significantly increased over 300%. The % of INTV/OBS trials has remained stable over the same time period (50–60%). Staff has increased from 6 coordinators to 10 with an additional 15 research associates allowing 24/7 service. With this significant growth, MACRO has become financially self-sufficient and additional outside departments now seek MACROs services.

Conclusions

Appropriate organization of acute care clinical research infrastructure minimizes redundancy and can promote sustainable, efficient growth in the current academic environment. Further studies are required to determine if similar models can be successful at other ACS programs.

Keywords: clinical research, infrastructure, acute care surgery

INTRODUCTION

Acute Care Surgery is evolving as a new specialty, providing a growing surgical work force to combat concerning emergency care shortages previously highlighted by the Institute of Medicine in 2006.1 The term ‘Acute Care Surgery’ was chosen to represent the essential areas of practice and scope including trauma care, emergency general surgery, and surgical critical care.2 Comparative effectiveness research documenting clinical outcome improvements has been touted as the next essential step for the evolving specialty, to ensure continued maturation and growth.2,3

Recently, large emergency care research networks across hospitals have been organized with a goal of promoting high-priority clinical research trials. These research networks are typically well funded, interdisciplinary, multicenter entities with clearly defined governance structure.4 Despite the important growth of these multicenter research networks, what constitutes an efficient and effective acute care clinical research infrastructure at an individual institution in the current academic and fiscal environment remains obscure. We sought to characterize the effects of implementation of a multidisciplinary acute care research organization (MACRO) at a busy tertiary referral university setting. We hypothesized that appropriate configuration of an acute care research organization could promote clinical research in a sustainable and efficient manner with the potential to become a model for similar Acute Care Surgery programs across the country.

METHODS

In 2008, to minimize redundancy, cost, and maximize existing resources promoting acute care research, MACRO was created unifying the clinical research infrastructure between the Departments of Critical Care Medicine, Emergency Medicine and Surgery.5 Prior to the implementation of MACRO, investigators would need to identify, recruit and train research personnel for each funded research study. At the conclusion of a study, much of the staff needed to be reassigned if funding was available. For industry studies and federal studies that provided a per patient reimbursement, investigators without other sources of funding or research infrastructure were unable to participate due to the inability to hire a percentage of a research coordinator. Since its creation, MACRO provides evaluation of study feasibility, regulatory submission and compliance, study set-up, patient screening and study execution, data management including database platform creation, and sample processing and storage. Over the time periods 2008–2012 we performed a retrospective analysis to characterize the changes over time following the creation of MACRO. The volume of clinical studies, patient enrollment for both observational (OBS) and interventional (INTV) trials, the specific departments utilizing MACRO services, the staff growth and the financial impact since MACRO’s origination were determined.

For comparison over time analyses Chi-square or analysis of variance ANOVA testing were used to compare categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively. A p value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

At the time of the creation of MACRO the chairs of each participating departments were designated as the steering committee for the organization. Physician representatives from each department, the clinical coordinator director and a biostatistician were appointed to the MACRO executive committee and meet monthly. The responsibilities of the executive committee include study selection and protocol feasibility, operations oversight, strategic planning and logistics of the organization. The clinical coordinator director of MACRO oversees daily operations, human resource utilization including research coordinator and research assistant staffing and budgetary oversight.

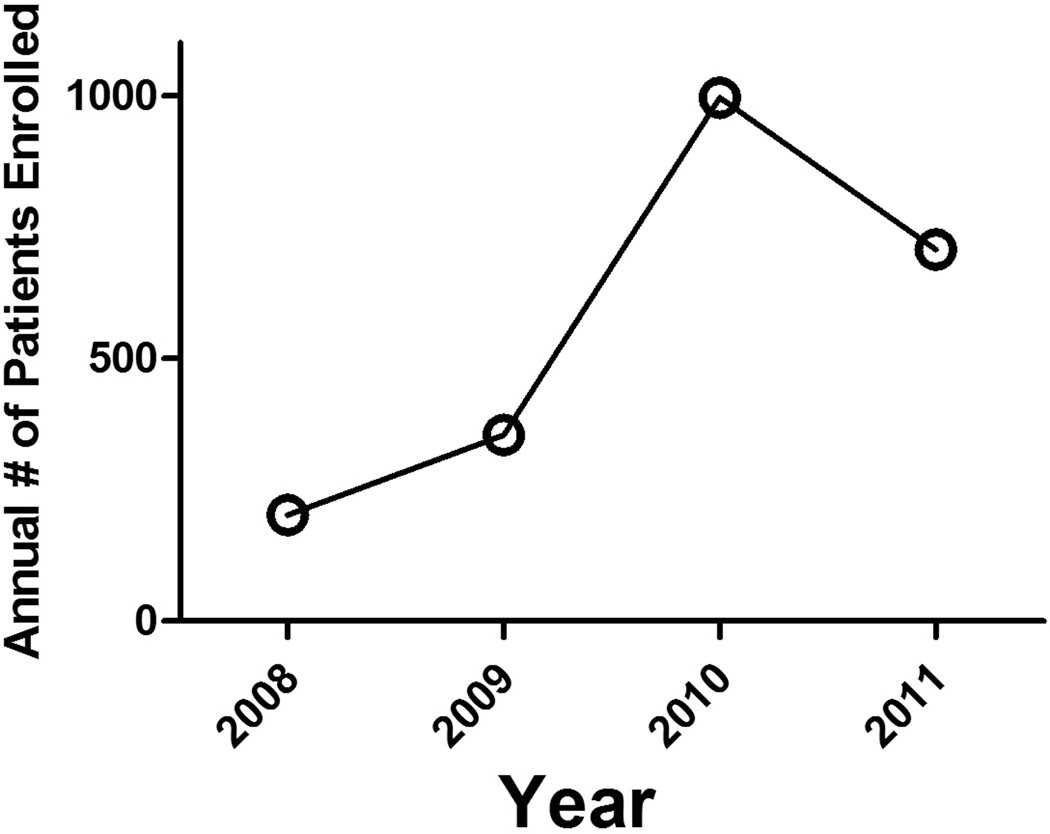

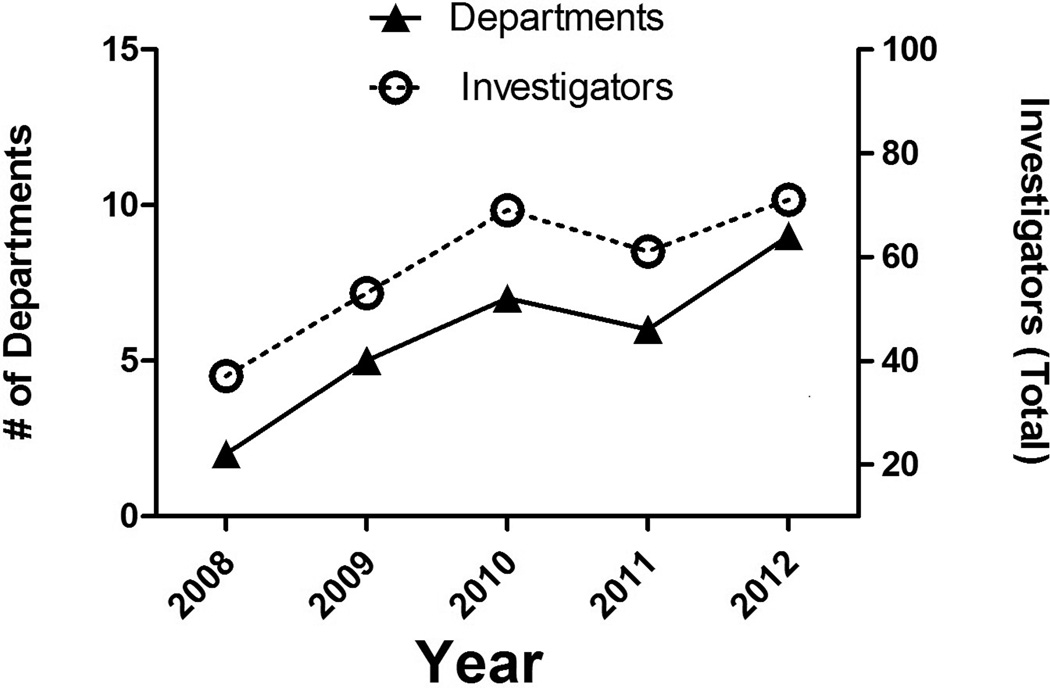

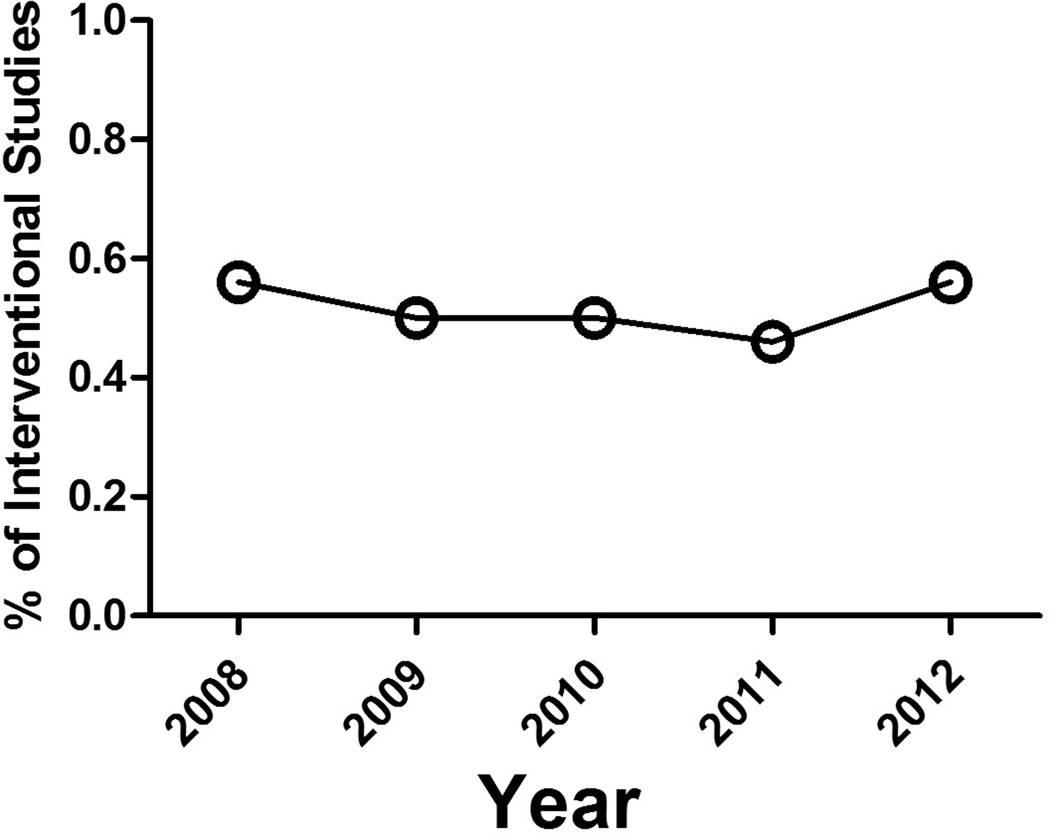

From 2008 to 2011, the volume of patients enrolled in clinical studies which MACRO facilitated significantly increased by over 340%. (Fig 1.) Staff increased from 6 clinical research coordinators to 10 coordinators with an additional 15 research associates being added who are primarily undergraduate students with medical field inclinations. The addition of these research associates allowed and promoted the transition to 24 hours / 7 days per week MACRO service availability. With this significant growth, increasing visibility and 24 hour service, outside departments began seeking MACRO’s services. Over 71 principal investigators and co-investigators from 9 different departments currently utilize MACRO services. (Figure 2.) Currently in 2012, MACRO’s services are being utilized for 14 INTV trials and 11 OBS trials. Importantly, the percentage of INTV trials relative to OBS trials has remained consistent over time irrespective of MACRO’s persistent growth. (Figure 3.)

Figure 1.

Annual number of patients enrolled in MACRO studies over time, p< 0.05.

Figure 2.

Number of individual deparments (left Y axis; triangles) and number of principal and co-investigators (right Y axis; circles) utilizing MACRO services over time. p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Percentage of MACRO studies that were interventional relative to observational over time, p=not significant.

The mission of MACRO was to facilitate clinical research led by a dedicated group of investigators in an ethical, regulatory compliant, and fiscally sound manner. As the growth of the research organization accelerated, outside department studies became more common and it was apparent that staffing needs for specific investigators fluctuated overtime. Because of these changes, a more transparent and adaptable method of billing for MACRO services was needed. In 2010, MACRO became a cost-center under the auspices of the Research/Cost Accounting Center at the University of Pittsburgh. This enabled MACRO to determine and evaluate cost efficiency and to allocate actual costs in a nonbiased and cost-neutral fashion across departments and institutions. With this more complex but efficient cost-center model, a financial research administrator was also required and ultimately incorporated into the infrastructure of MACRO.

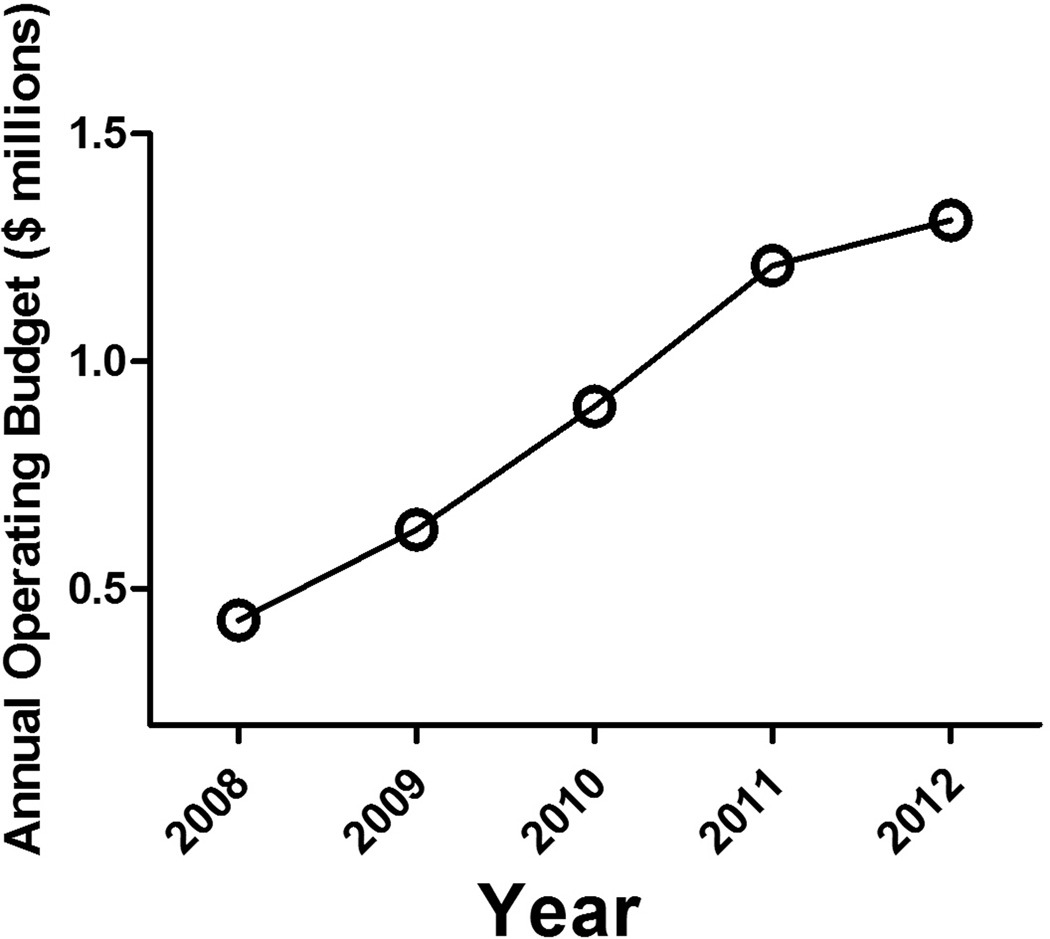

The annual operating budget, as expected with the growth of MACRO services being provided, also has dramatically increased. (Figure 4.) For the current year 2012, the MACRO operating budget was over 1.3 million dollars.

Figure 4.

Annual operating budget ($ millions) for MACRO over time, p< 0.05.

DISCUSSION

As Acute Care Surgery continues to evolve as a surgical specialty, documentation of outcome improvements or areas where improvements are needed will be essential for the continued maturation and validation of the specialty.2,3 Although large research networks have been successful in promoting important clinical trials in their respective focus areas, what constitutes an appropriate research model at a single institution remains poorly defined.4,6,7 The current analysis provides insight for such a clinical research organization and suggests that a multi-departmental model, with appropriate leadership, support, governance and infrastructure can provide the backdrop for sustainable and efficient growth of clinical and translational research.

By definition, emergency care has no time restraints with a large portion of care being provided during ‘non-business hours’.8 Accordingly, successful clinical research infrastructure that promotes and allows services to be provided during these same time periods will result in a large untapped patient population with clinical investigation enrollment potential. The enrollment growth which occurred over time was spurred in a large part by the addition of the research associates who resided in the emergency department, trauma bay and ICU floors with a primary goal of identifying potential candidates for study enrollment. The hiring of such a work force was mutually beneficial and economically efficient. The undergraduate students derived important medical research experience and a resume building source of income, while MACRO continues to benefit both from increased patient enrollment and visibility with ‘troops always on the ground’ throughout the hospital.

Multiple factors have assisted in the growth of MACRO at our institution. Of primary importance is the support and backing from the involved departments of the institution. Leadership and governance derived from the executive committee, including representatives from each respective department with significant clinical research experience, who are stake holders in the success of the organization, provides an organizational structure with significant capabilities and potential. In addition to the increased passive visibility that occurred with growth, active visibility was promoted utilizing clinical research rounds throughout ICUs, outreach to individual attending staff across departments and standard advertising using pamphlets, pens, brochures, research billboards and MACRO apparel which is readily recognized for the research staff.

With this growth, multi-center trials have also become more common and MACRO’s services have increasingly included coordinating center responsibilities, FDA approval processing and overall multi-center project management. Similar to the large emergency care research networks such as the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC)9, Emergency Medicine Network (EMNet)10 and Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trial (NETT)11, MACRO’s infrastructure exists and requires no investment or development de novo by individual investigators with varied needs. This readily available, efficient infrastructure is the primary reason for additional departments utilizing MACRO’s services and its consistent growth.

Since MACROs creation, efficiency has been a primary focus of the organization. The ‘troops on the ground’ infrastructure and the inroads with regulatory bodies which promotes a streamlined regulatory approval process. Any increasing efficiency over time has occurred with increasing staff and the cost-center model changes which are felt directly by the individual investigator.

There are limitations to the current analysis. It is a retrospective study at a single institution and may not be applicable or pertinent to other institutions with different departmental organizations or academic makeup. Data from before the origination of MACRO was not available for a true comparison (before and after) and we were limited to comparisons over time since MACRO’s origination. This includes the ability to determine the efficiency parameters brought about by MACROs creation. Due to the variability in specific inclusion criteria for individual studies, the current growth in enrollment may not be persistent and has the potential to vary over time irrespective of any staff growth or the number of departments utilizing MACRO’s services. Although presented under the umbrella of Acute Care Surgery, studies which MACRO provides services for are not required to be focused on surgical studies. The majority of studies for which MACRO provides their services are acute care research studies which involve emergency department enrollment and intensive care admission. Importantly, despite outside departments increasingly utilizing MACROs services, it is these types of studies for which MACROs services are most beneficial to the investigator because of the clinical research infrastructure provided in these areas.

In conclusion, the current analysis suggests that appropriate organization of acute care clinical research infrastructure minimizes redundancy and can promote sustainable, efficient, multi-departmental growth in the current academic environment. Further studies are required to determine if similar acute care research models can be successful at other ACS programs across the country.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: NIH NIGMS K23GM093032.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This paper was presented as an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma in Pheonix, AZ, Jan 11th–15th, 2013.

REFERENCES

- 1.Knudson K, Raeburn CD, McIntyre RC, Jr, et al. Management of duodenal and pancreaticobiliary perforations associated with periampullary endoscopic procedures. Am J Surg. 2008 Dec;196(6):975–981. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.07.045. discussion 981-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Britt LD. Acute care surgery: what's in a name? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012 Feb;72(2):319–320. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31824b15c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frankel HL, Butler KL, Cuschieri J, et al. The role and value of surgical critical care, an essential component of Acute Care Surgery, in the Affordable Care Act: a report from the Critical Care Committee and Board of Managers of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012 Jul;73(1):20–26. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31825a78d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papa L, Kuppermann N, Lamond K, et al. Structure and function of emergency care research networks: strengths, weaknesses, and challenges. Acad Emerg Med. 2009 Oct;16(10):995–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. http://www.ccm.pitt.edu/macro. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Govindarajan P, Larkin GL, Rhodes KV, et al. Patient-centered integrated networks of emergency care: consensus-based recommendations and future research priorities. Acad Emerg Med. 2010 Dec;17(12):1322–1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baren JM, Middleton MK, Kaji AH, et al. Evaluating emergency care research networks: what are the right metrics? Acad Emerg Med. 2009 Oct;16(10):1010–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carr BG, Reilly PM, Schwab CW, Branas CC, Geiger J, Wiebe DJ. Weekend and night outcomes in a statewide trauma system. Arch Surg. 2011 Jul;146(7):810–817. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rooney M, Kish J, Jacobs J, et al. Improved complete response rate and survival in advanced head and neck cancer after three-course induction therapy with 120-hour 5-FU infusion and cisplatin. Cancer. 1985 Mar 1;55(5):1123–1128. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850301)55:5<1123::aid-cncr2820550530>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsay AD, Rooney N. Lymphomas of the head and neck. 1: Nasofacial T-cell lymphoma. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1993 Apr;29B(2):99–102. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(93)90029-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirimai K, Chalermchockcharoenkit A, Roongpisuthipong A, Pongprasobchai S. Associated risk factors of human papillomavirus cervical infection among human immunodificiency virus-seropositive women at Siriraj Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004 Mar;87(3):270–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]