Abstract

Summary

Background

Antithrombin (AT) is a plasma serpin inhibitor that regulates the proteolytic activity of procoagulant proteases of the clotting cascade. In addition to its anticoagulant activity, AT also possesses potent antiinflammatory properties.

Objectives

The objective of this study is to investigate the antiinflammatory activity of wild-type AT (AT-WT) and a reactive center loop mutant of AT (AT-RCL) which is not capable of inhibiting thrombin.

Methods

Cardioprotective activities of AT-WT and AT-RCL were monitored in a mouse model of ischemia/reperfusion injury in which the left anterior descending coronary artery was occluded and then released.

Results

We demonstrate that AT markedly reduces myocardial infarct size by a mechanism that is independent of its anticoagulant activity. Thus, AT-RCL attenuated myocardial infarct size to the same extent as AT-WT in this acute injury model. Further studies revealed that AT binds to vascular heparan sulfate proteoglycans via its heparin-binding domain to exert its protective activity as evidenced by the therapeutic AT-binding pentasaccharide (fondaparinux) abrogating the cardioprotective activity of AT and a heparin-site mutant of AT exhibiting no cardioprotective property. We further demonstrate that AT up-regulates production of prostacyclin in myocardial tissues and inhibits expression of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 in vivo by attenuating ischemia/reperfusion-induced JNK and NF-κB signaling pathways.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that both AT and the non-anticoagulant AT-RCL, through their antiinflammatory signaling effects, elicit potent cardioprotective responses. Thus, AT may have therapeutic potential for treating cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Keywords: antithrombin, heparin, ischemia, inflammation, signal transduction

Introduction

Antithrombin (AT) is a serine protease inhibitor of the serpin superfamily which regulates proteolytic activities of procoagulant proteases of both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways [1,2]. The primary protease targets for AT are believed to be thrombin, factor Xa (FXa) and factor IXa which are inhibited with a 1:1 stoichiometry through an Arg residue in the reactive center loop (RCL) of AT functioning as a bait and trapping the protease in the form of inactive enzyme-inhibitor complex 3,4]. The optimal inhibitory activity of AT requires the cofactor function of heparin which accelerates protease inhibition by AT by greater than three orders of magnitude [1,2]. This is the basis for widespread use heparins as anticoagulants in cardiovascular medicine [5]. Therapeutic heparins, depending on their size, bind to a basic loop of AT to conformationally activate the serpin or bind to both the serpin and the protease to promote their binary interaction through a bridging mechanism [1–3,6]. It is thought that the interaction of AT with heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) that line the microvasculature can also promote the reactivity of the serpin with coagulation proteases by similar mechanisms [7,8].

It is known that in addition to improving its anticoagulant activity, the interaction of AT with vessel wall HSPGs also confers potent antiinflammatory and antiangiogenic properties to the serpin [9,10]. Several studies in cellular and animal models have demonstrated that AT binds to specific vessel wall HSPGs via its basic residues of the heparin-binding D-helix to elicit intracellular signaling responses in vascular endothelial cells [10,11]. Interestingly, the conformational specific interaction of AT with different HSPG molecules plays a key role in determining the signaling specificity of the serpin. Thus, it has been demonstrated that the binding of low-affinity heparin conformers of AT (cleaved or latent forms) to vessel wall HSPGs elicits antiangiogenic responses [12,13]. However, the native high-affinity heparin conformer of AT appears to initiate antiinflammatory responses in vascular endothelial cells [14–16]. The mechanism by which different AT conformers exhibit distinct signaling responses through interaction with vessel wall HSPGs is not understood. It has been hypothesized that cleaved and latent conformers of AT induce expression of specific genes that are involved in cellular apoptosis and cell cycle arrest [17]. By contrast, it is thought that the native high-affinity heparin conformer of AT can bind to specific vessel wall HSPGs containing a 3-O-sulfate (3-OS) moiety [18], thereby inducing synthesis of prostacyclin (PGI2) in vascular endothelial cells. PGI2 can elicit protective antiinflammatory responses through inhibition of activation of NF-kB in cytokine stimulated endothelial cells [7,10,14–16]. A PGI2-mediated protective function for AT has been demonstrated in both models of kidney and liver ischemia/reperfusion injury in in vivo systems [14,19]. Similar to other anticoagulants, increased bleeding risk remains a major concern in AT-therapy if the serpin is ever approved as an antiinflammatory drug for treating ischemia/reperfusion injury in humans [20].

In this study, we investigated the cardioprotective activity of wild-type AT (AT-WT) and a mutant of it in which the RCL (P3-P3′ positions) has been replaced with the FXa recognition site on prothrombin so that the mutant (AT-RCL) becomes essentially un-reactive with thrombin [21], thus possessing dramatically reduced anticoagulant activity [22]. In a mouse model of ischemia/reperfusion injury in which the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) was occluded and then released, we demonstrate that both AT-WT and AT-RCL markedly reduce the myocardial infarct size by a concentration dependent manner. Our results indicate that AT up-regulates production of PGI2 in myocardial tissues and down-regulates proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 in vivo by attenuating the ischemia/reperfusion-induced JNK and NF-κB signaling pathways.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Male C57BL/6J mice (4–6 months of age) were used in all experiments. All animal protocols in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University at Buffalo-State University of New York.

Infarct size measurement

C57BL/6J mice were anesthetized, intubated, and ventilated with a respirator (Harvard apparatus, Holliston, MA) as described [23,24]. After left lateral thoracotomy, the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) was occluded for 20 min with 8-0 nylon suture and polyethylene tubing to prevent arterial injury and reperfused for up to 3h. Vehicle (Hepes buffer) or AT was administered via the tail vein injection 5 min before reperfusion. The ECGs confirmed the ischemic hallmark ST-segment elevation during coronary occlusion (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Cardiectomy was performed at the conclusion of reperfusion. Left ventricular ischemic regions were isolated prior to freeze clamping in liquid nitrogen. Sham refers to same surgical procedures without occlusion.

For infarct size measurement, hearts were reperfused for 3h, and then excised for dual staining. The non-necrotic tissue in the ischemic region was stained red with 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetrazolium (TTC), and non-ischemic regions were stained blue with Evans blue dye. The hearts were fixed and sectioned into 1 mm slices, photographed utilizing a Lexica MZ95 microscope, and analyzed by NIH Image analysis software [23,24]. The myocardial infarct size was calculated as the ratio of the percentage of myocardial necrosis to the ischemic area at risk (AAR).

Cardiac troponin-I assay

Mice were completely exsanguinated after 20 min of ischemia and 3h of reperfusion. Serum levels of the cardiac-specific isoform of troponin-I were assessed using an ELISA kit (Life Diagnostics (West Chester, PA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Immunoblotting

Heart homogenate proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against phospho-JNK, total JNK, phospho-NF-κB p65, total NF-κB p65 and IκBα (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) were used to analyze expression levels of signaling molecules as described [23–25].

Measurement of cardiac 6-keto-PGF1α

Cardiac 6-keto-PGF1α (a metabolite of prostacyclin, PGI2) levels were determined in animals subjected to I/R before and 1, 3 and 6h after reperfusion as described [14].

Assay of cardiac cytokines

Cardiac tissue levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were measured using ELISA kits for TNF-α (Genzyme Corporation, Cambridge, MA) and IL-6 (R & D System). Following 3 or 6h reperfusion, the hearts were removed, weighed, and homogenized using 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.05% sodium azide at 4°C. Homogenates were sonicated for 20s and centrifuged (2000g for 10 min at 4°C) and resulting supernatants were stored at −80°C until use. The total protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method. Cytokine levels were normalized to the total protein concentration.

The heart RNA was purified using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) and RNAeasy (Qiagen Inc, Valencia, CA). cDNA was synthesized using the ThermoScriptTM RT-PCR system (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) at a concentration of 100ng RNA. Quantitative PCR was then conducted on 1 μL cDNA plus SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) using an iCycler Q-PCR machine (Bio-Rad). For each target gene, a standard curve was constructed and the starting quantity (SQ) of mRNA was calculated using the Bio-Rad iCycler iQ-5 real-time PCR detection system software. Results for each sample was normalized by dividing SQ of the target gene by SQ of β-actin for that same sample. Pro-inflammatory cytokine gene primers were designed based on our previous publications [24,25]. The same left ventricular regions for all groups were taken for analysis.

Histological evaluation

Following I/R, the hearts were perfused with relaxation buffer (25 mM KCl and 5% dextrose in PBS) with heparin to wash out blood. The hearts were removed, fixed in 10% formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded myocardial sections (5 μm), stained with hematoxylin and eosin, were examined by light microscopy. To demonstrate neutrophils within the myocardium of the I/R region, paraffin-embedded myocardial sections from vehicle, I/R and I/R plus AT mice were treated with Leder stain (fuchsin acid, sodium nitrite, and naphthol AS-D chloroacetate esterase in PBS), which identifies chloroacetate esterase within neutrophils, and examined by light microscopy.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means ± S.E. Data were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA to measure statistical significance. For single- and multi-factorial analyses, appropriate post-hoc test(s) were performed to measure individual group differences of interest. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

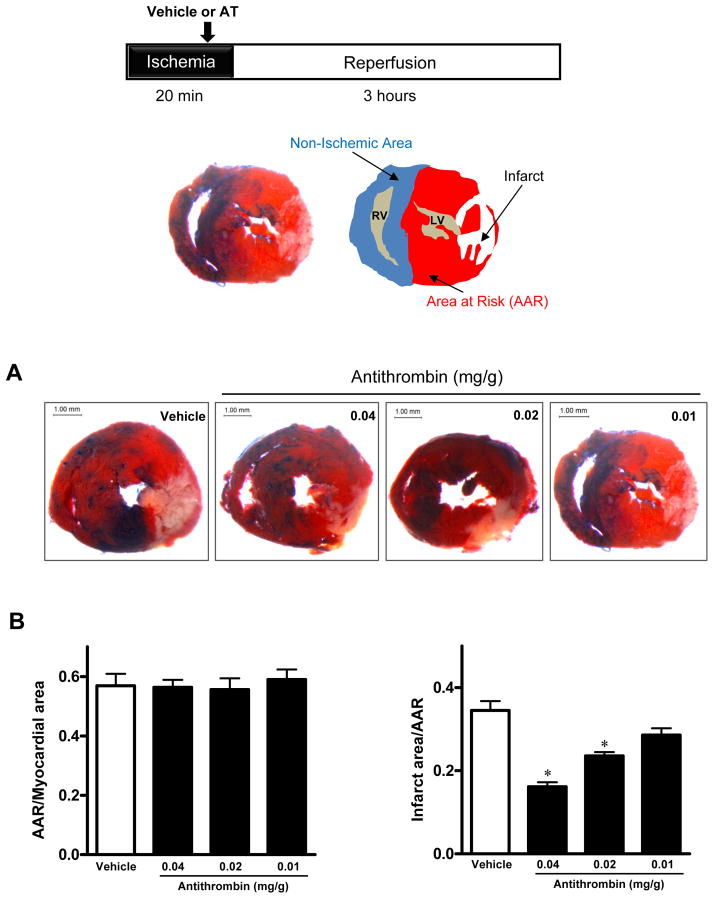

AT reduces myocardial infarction during I/R

To determine whether AT protects against myocardial injury, we first examined the effect of 3 different concentrations of AT on myocardial infarction. C57BL/6 mice were subjected to 20min of ischemia followed by 3h of reperfusion (Fig. 1A). At each dose, AT or vehicle (Hepes buffer) was injected intravenously via the tail vein 5min before starting reperfusion. Representative cardiac sections dually stained with TTC and Evans blue dye are shown in Fig. 1. Ratios of the area at risk (red) (Fig. 1A) to total myocardial area were equal among the 4 groups (Fig. 1B), indicating that a similar ischemic stress has been induced in all groups. Administration of AT-WT at 0.02 mg/g dosage (0.5 mg/25g mouse) or higher significantly decreased myocardial infarction in mice (21.6% ± 1.1%, 0.02 mg/g, 16.9 ± 3.3%, 0.04 mg/g; vs. 33.8 ± 1.06% vehicle, p<0.05 vs. vehicle), whereas the lowest dosage (0.01 mg/g), while decreased the infarct size (26.2% ± 3.1% vs. 33.8 ± 1.06% vehicle) but differences did not reach a statistical significance. These results indicate that AT reduces myocardial infarction in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 1.

AT dose-dependently reduces myocardial infarct size after I/R. Hearts were subjected to 20min ischemia followed by 3h reperfusion. Different doses of AT (0.01, 0.02 or 0.04 mg/g weight) or Hepes buffer (200 μL) were administered via the tail vein 5min before reperfusion. The extent of myocardial necrosis was assessed as described under “Materials and methods”. (A) Representative sections of myocardial infarction. (B) The ratio of area at risk (AAR) to myocardial area (left panel) and the ratio of infarct area to AAR (right panel). Values are means ± S.E. from 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs. vehicle.

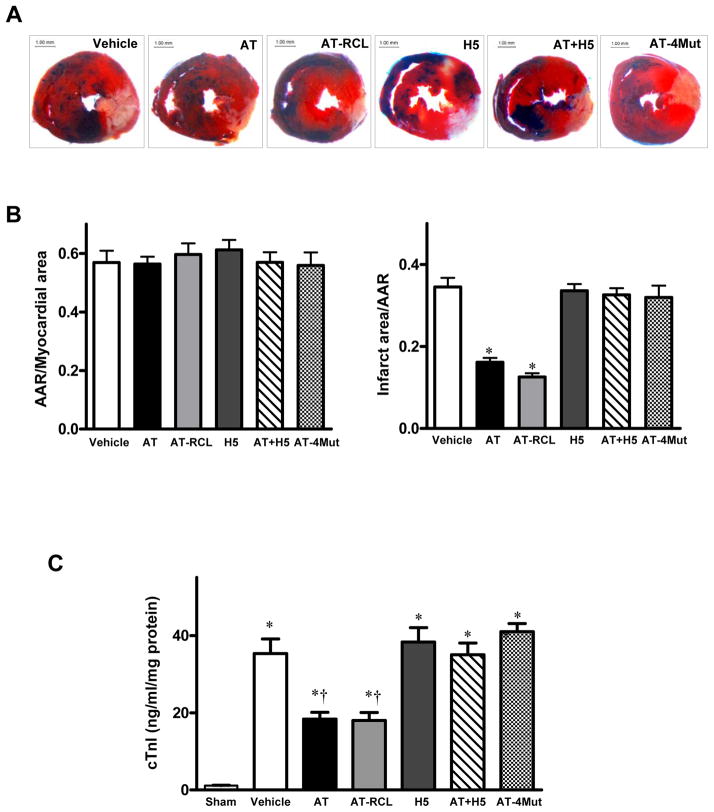

Cardioprotective activity of AT is independent of its anticoagulant effect

To further investigate whether AT decreases myocardial infarction through an anticoagulant effect or whether its signaling effect is responsible for cardioprotective properties, we evaluated the protective activity of AT-RCL in the same I/R model. AT-RCL is un-reactive with thrombin and other coagulation enzymes with the exception of FXa [21,22]. AT-RCL reacts with FXa with a rate constant that is ~5–10-fold slower than that of AT-WT [21,27]. A decrease similar to that observed with AT-WT in the infarct size was also observed with a single dose of 0.04 mg/g of AT-RCL (18.5 ± 3.1%, p<0.05 vs. vehicle, Fig. 2), suggesting the antiinflammatory activity of AT is primarily responsible for the cardioprotective activity of the serpin. The antiinflammatory effect of AT is mediated through its binding to cell surface HSPGs via its heparin-binding D-helix. In support of this hypothesis, fondaparinux (H5), a synthetic therapeutic pentasaccharide which binds to D-helix of AT [6], abrogated the cardioprotective effect of the serpin in this injury model (Fig. 2). Further support for this hypothesis is provided by the observation that an AT mutant lacking affinity for heparin (AT-4Mut), but having normal reactivity with FXa [28] exhibited no cardioprotective activity (Fig. 2). This result rules out the possibility that FXa inhibition by AT-RCL contributes to its cardioprotective activity. Fondaparinux can catalyze rapid inhibition of mouse FXa by mouse AT. It also did not exhibit any protective activity (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Cardioprotective effect of AT is mediated through interaction with HSPGs independent of its anticoagulant activity. Hearts were subjected to 20min ischemia followed by 3h reperfusion. AT derivatives (AT-WT, AT-RCL, AT-4Mut, AT-WT + fondaparinux (H5) (0.04 mg/g) and H5 by itself (0.08 mg/g) or Hepes buffer were administered via the tail vein 5min before reperfusion. The extent of myocardial necrosis was assessed as described under “Materials and methods”. (A) Representative sections of myocardial infarction; (B) The ratio of area at risk (AAR) to myocardial area (left panel) and the ratio of infarct area to AAR (right panel). Values are means ± S.E. from 3 independent experiments. *p<0.01 vs. vehicle. (C) Serum cardiac troponin-I (cTn) in sham-, vehicle- and AT-treated mice. Values are means ± S.E. from 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs. sham, †p<0.05 vs. vehicle.

Analysis of circulating plasma levels of the cardiac-specific isoform of troponin-I (cTnI), as an additional marker of myocardial injury, indicated that both AT-WT and AT-RCL exert similar and potent cardioprotective effects at a concentration of 0.04 mg/g (Fig. 2C). In agreement with results presented above, the heparin-binding defective AT-4Mut did not exhibit any activity in this assay and pre-incubation of AT-WT with an equimolar concentration of fondaparinux effectively abrogated this protective function of AT (Fig. 2C).

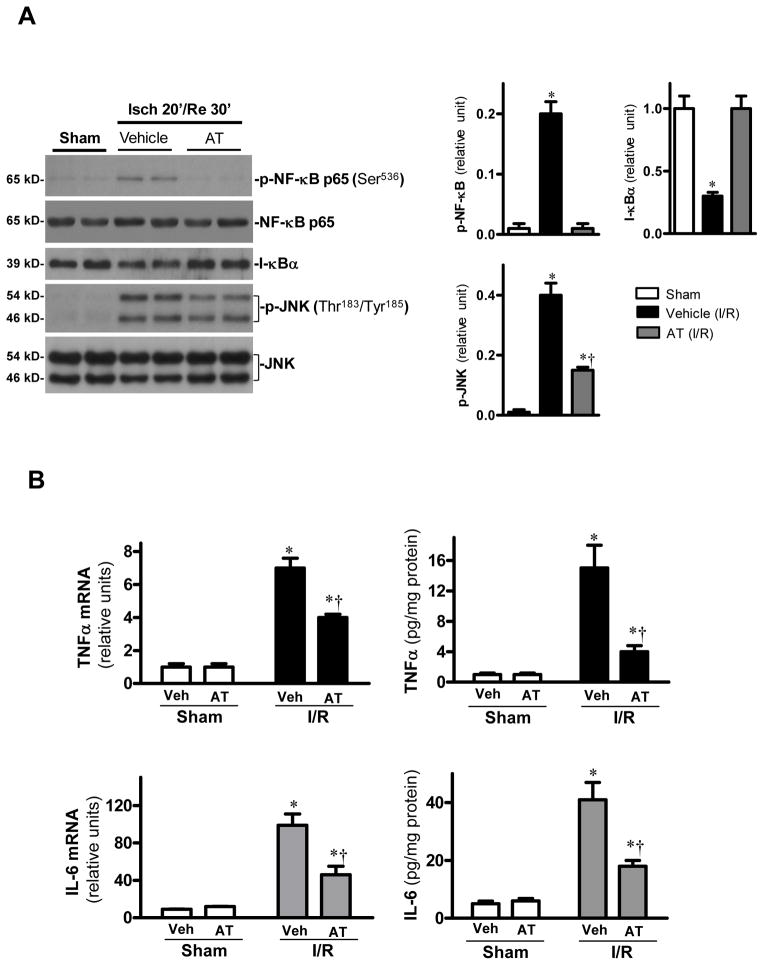

Cardioprotective activity of AT is associated with inhibition of NF-κB

AT is a specific inhibitor of the NF-κB pathway in both LPS and TNF-α treated monocytes and endothelial cells [14,26]. NF-κB plays a critical role in inflammatory responses and the blockade of NF-κB activation improves cardiac function and survival after myocardial infarction [29]. We investigated the effect of AT and AT-RCL on the NF-κB pathway in the I/R injury model. Results presented in Fig. 3A (data presented for AT-WT only) revealed that both AT derivatives markedly down-regulate NF-κB phosphorylation (p-p65, Ser536) after 30min reperfusion. Activation of NF-κB requires dissociation and degradation of its inhibitory protein I-κB [30]. The protein level of I-κB was decreased by ischemia/reperfusion, and the loss of I-κB was associated with the occurrence of phosphorylated NF-κB after 30min of reperfusion. However, both AT derivatives inhibited the I/R-induced I-κB degradation (Fig. 3A, shown for AT-WT only). In addition to inhibition of NF-κB activation, AT and AT-RCL also reduced the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) phosphorylation during I/R (Fig. 3A, shown for AT-WT only). JNK is a stress-activated protein kinase whose phosphorylation can be stimulated by inflammatory stress [31]. The activation and subsequent translocation of JNK into the nucleus phosphorylates transcription factors involved in regulation of expression of cytokines [31]. The attenuation of JNK phosphorylation was associated with reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNFα and IL-6 at both mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 3B, shown for AT-WT only).

Figure 3.

AT reduces cardiac inflammatory responses after I/R. (A) The phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 is decreased by AT (0.04 mg/g) during I/R. AT treatment attenuates JNK phosphorylation during I/R. Value are means ± S.E., n=4–5, *p<0.05 vs. sham, †p<0.05 vs. I/R vehicle. (B) AT reduces mRNA expression and protein levels of TNFα and IL-6 in hearts after I/R. Values are means ± S.E., n=4–5. *p<0.05 vs. sham, respectively, †p<0.05 vs. I/R vehicle.

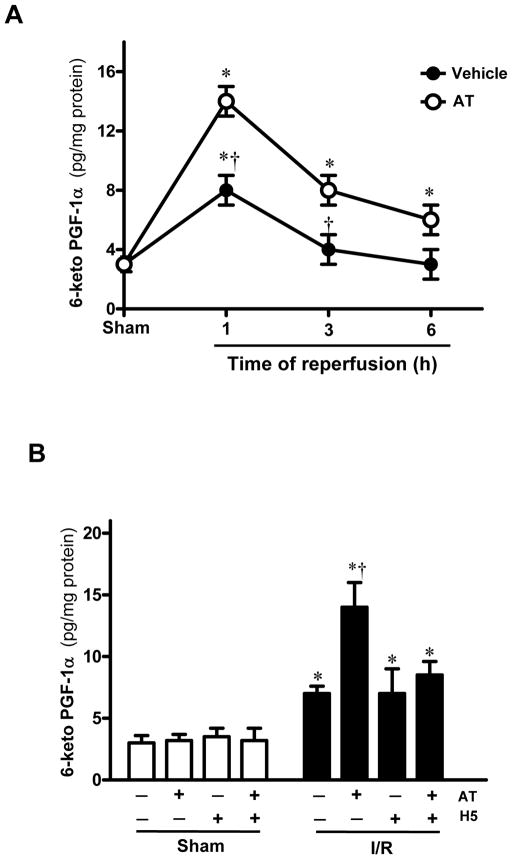

Cardioprotective effect of AT is associated with induction of prostacyclin

To examine the effect of AT on prostacyclin (PGI2) release, cardiac tissue levels of 6-keto-PGF1α during ischemia/reperfusion was evaluated. As presented in Fig. 4A, 6-keto-PGF1α levels were increased after ischemia/reperfusion in vehicle groups, peaking after 1h of reperfusion. AT significantly augmented I/R-induced 6-keto-PGF1α levels in cardiac tissues after 1h reperfusion (Fig. 4B). However, AT (0.04 mg/g) co-incubated with an equimolar concentration of fondaparinux did not have any effect on 6-keto-PGF1 α levels, suggesting that interaction of AT with HSPGs is responsible for the protective prostacyclin-inducing effect of the serpin (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of AT on myocardial levels of 6-keto-PGF1α in mice subjected to I/R. (A) Myocardial levels of 6-keto-PGF1α were determined during sham or indicated time points of reperfusion after 20min ischemia with or without AT (0.04 mg/g) treatment 5min before reperfusion. (B) Myocardial levels of 6-keto-PGF1α were determined at 1h of reperfusion after 20min ischemia in mice with or without AT or AT + H5 treatment 5min before reperfusion. Data are expressed as means ± S.E. for 4 animals in each group. *p<0.05 vs. sham operated group, respectively; †p<0.05 vs. I/R vehicle, respectively.

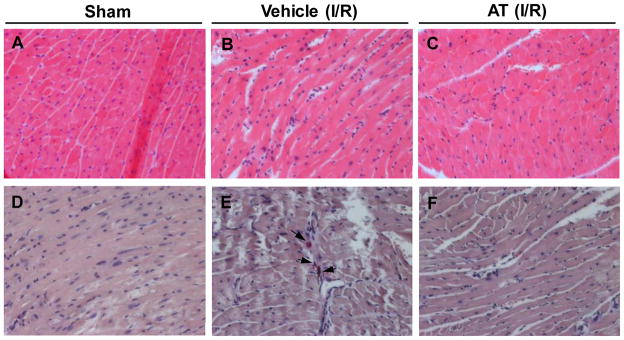

AT inhibits leukocyte infiltration

Histologic analyses of the hearts (Fig. 5) demonstrated that ischemia/reperfusion induced mild interstitial changes including leukocyte infiltration, interstitial hypercellularity, and fibrosis (Fig. 5B). The Leder-stained myocardial sections demonstrated that infiltrating leukocytes include neutrophils (Fig. 5E). AT-treatment reduced ischemia/reperfusion-induced hispathological changes (Fig. 5C and F) that reflect the antiinflammatory activity of AT in the ischemic heart.

Figure 5.

Histopathologic changes in I/R injured hearts. Left ventricular sections from representative mice are shown. (A) and (D) sham, (B) and (E) ischemia 20min and reperfusion 3h, (C) and (F) I/R (20min/3h) + AT (0.04 mg/g) treatment. (A–C) are stained with hematoxylin and eosin, demonstrating interstitial hypercellularrity with fibrosis and mild leukocyte infiltration. (D–F) are stained with Leder, which specifically detects chloroacetate esterase in neutrophils, suggesting infiltrating leukocytes include neutrophils.

Discussion

In this study for the first time we demonstrate that AT exerts a potent cardioprotective effect during I/R injury by a mechanism that is largely independent of its anticoagulant activity. This is derived from the observation that AT-RCL, which is incapable of inhibiting thrombin, decreased infarct size to the same extent as AT-WT during I/R in the injured heart. The observation that fondaparinux abrogated the cardioprotective activity of AT further supports the hypothesis that the interaction of D-helix of the serpin with cell surface HSPGs is required for the protective activity of AT. Additional support for this hypothesis is provided by the observation that the heparin-binding defective D-helix mutant AT-4Mut, which has no affinity for heparin [28], exhibited no cardioprotective activity. In agreement with previous results in renal and hepatic injury models [14,19], the cardioprotective activity of AT was associated with the serpin inducing PGI2 expression, thereby inhibiting I/R-induced JNK and NF-κB pathways and attenuating production of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6. The expression of these proinflammatory cytokines are known to increase plasma levels of troponin-I which can be released by cardiomyocytes during I/R injury [32]. Troponin-1 is a well-known cardiac biomarker and its elevated level is associated with severity of cardiac injury and correlates with poor prognosis in patients with myocardial infarction [32,33]. The observation that both AT-WT and AT-RCL decreased the plasma level of troponin-I further suggests that AT has a potent cardioprotective activity and that this AT function is independent of its anticoagulant effect. The protective effect of AT on troponin-I was abolished by fondaparinux and absent in AT-4Mut, further supporting the hypothesis that interaction of AT with specific HSPGs is responsible for its antiinflammatory function.

Unlike its relatively well-investigated anticoagulant effect, the antiinflammatory mechanism of AT is not well understood. Thus, specific cell surface receptor(s) that may be involved in transducing signaling effects of AT has not been characterized. It is, however, known that selected vascular HSPGs possess minute quantities of a distinct 3-OS containing heparin sequence which can bind to AT with a high affinity [2,7,8,18]. It is well-established that therapeutic heparins contain this unique sequence which can bind to D-helix of AT with high-affinity to conformationally activate the serpin [1,2,6]. It is believed that AT interaction with 3-OS containing HSPGs may also be responsible for its signaling activity [18]. Thus, it has been found the knockout mutant of mice lacking the enzyme responsible for the synthesis of 3-OS (HS 3-OST-1) exhibit normal hemostatic function, however, they show a proinflammatory phenotype and, unlike wild-type mice, they do not respond to AT if challenged with LPS, suggesting that AT signaling through 3-OS containing vascular HSPGs may be responsible for protective effects of the serpin [18]. Further studies using HS 3-OST-1 knockout mice will be required to determine whether AT interaction with 3-OS containing HSPGs in myocardial tissues is also responsible for its cardioprotective activity during I/R injury.

It is known that AT interacts with 3-OS containing pentasaccharide with a dissociation constant of 10–20 nM [1–3]. Noting the high plasma concentration of AT (>2 μM), it is expected that 3-OS containing HSPGs will all be bound by the native AT. Thus, if the hypothesis that AT binding to the 3-OS containing HSPGs is responsible for its signaling function, an intriguing question that remains to be answered is why should there be a requirement for high concentrations of exogenous AT to initiate protective signaling in vascular endothelial cells. One possibility is that in addition to high-affinity 3-OS containing HSPGs, AT interaction with other lower-affinity binding sites is also required for its signaling function. Recently, we demonstrated that both AT-WT and AT-RCL elicit antiinflammatory activities in response to LPS in endothelial cells through the PGI2-dependent inhibition of NF-κB [26]. Interestingly, further analysis revealed that both siRNA for the syndecan-4 HSPG and pertussis toxin abrogate the protective cellular function of AT, suggesting that in addition to HSPGs, the activation of a G-protein coupled receptor, which signals through Gi/o-protein, is also required for the protective signaling mechanism of AT [26]. Given that the HSPG family of receptors do not directly signal through coupling to G-proteins, crosstalks among a network of different receptors may be required for the protective signaling mechanism of AT. Thus, much more research work is needed to understand the exact mechanism by which AT elicits protective signaling responses in myocardial tissues.

In addition to its protective effect during I/R, AT exhibits potent antiinflammatory effects in animal models of severe sepsis [10,20]. However, in a randomized clinical trial, AT did not show a beneficial effect on the mortality rate in patients with severe sepsis, though this study also used a low-dose of heparin concomitant with AT which may have antagonized its protective effect in septic setting [20]. This hypothesis is strengthened by the observation that post-hoc analysis of a subgroup of patients receiving a high-dose AT without heparin showed a survival benefit in the 90-day mortality rate [10,20]. Nevertheless, a clear mortality reducing effect for AT was not observed in another clinical trial with severe sepsis, except that its long term usage at high concentrations was found to be beneficial in regulating procoagulant responses in patients [34]. Despite the apparent negative data in human clinical trials with severe sepsis, the cardioprotective activity of AT against cardiac I/R warrants further investigation in human clinical trials. Although much more additional work is required to assess the AT effect in severe sepsis, nevertheless, severe sepsis is a complex systemic inflammatory disorder with pathologies completely different than those in I/R injury. It is possible that systemic vascular inflammation caused by sepsis eliminates/down-regulates the 3-OS and/or other unknown receptors, thereby compromising the signaling effect of AT. The same scenario may not hold true in the acute cardiac I/R injury. Nevertheless, due to a requirement for high-dose of AT in order to observe a protective effect, bleeding remains a concern in AT-therapy. In light of our data that the non-anticoagulant AT-RCL retains its cardioprotective activity, this AT variant may have superior therapeutic utility if AT is ever approved for treating cardiac I/R injury.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Rezaie for proofreading the manuscript.

Source of Funding

This work was supported by grants awarded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health HL 62565 and HL 101917 to ARR; and by American Heart Association SDG0835169N and 12GRNT11620029, and American Diabetes Association Basic Science 1-11-BS-92 to JL.

Footnotes

Authorship contributions

J.W. designed experiments, analyzed data and performed research; Y.W., J.W., J.G., C.T., and C.M. performed research; J.L. designed experiments, performed research, analyzed data and wrote the paper; A.R.R. designed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the paper.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Olson ST, Björk I, Shore JD. Kinetic characterization of heparin-catalyzed and uncatalyzed inhibition of blood coagulation proteinases by antithrombin. Methods Enzymol. 1993;222:525–60. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)22033-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin L, Abrahams J, Skinner R, Petitou M, Pike RN, Carrell RW. The anticoagulant activation of antithrombin by heparin. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1997;94:14683–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gettins PGW. Serpin structure, mechanism, and function. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4751–803. doi: 10.1021/cr010170+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence DA. The serpin-proteinase complex revealed. Nature Struct Biol. 1997;4:339–41. doi: 10.1038/nsb0597-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weitz JI, Hirsh J. Antithrombins: their potential as antithrombotic agents. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:9–16. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.43.020192.000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huntington JA, McCoy A, Belzar KJ, Pei XY, Gettins PGW, Carrell RW. The conformational activation of antithrombin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15377–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcum JA, Rosenberg RD. Anticoagulantly active heparin-like molecules from the vascular tissue. Biochemistry. 1984;23:1730–7. doi: 10.1021/bi00303a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damus PS, Hicks M, Rosenberg RD. Anticoagulant action of heparin. Nature. 1973;246:355–7. doi: 10.1038/246355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Reilly MS, Pirie-Shepherd S, Lane WS, Folkman J. Antiangiogenic activity of the cleaved conformation of the serpin antithrombin. Science. 1999;285:1926–8. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roemisch J, Gray E, Hoffmann JN, Wiedermann CJ. Antithrombin: a new look at the actions of a serine protease inhibitor. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2002;13:657–70. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rein CM, Desai UR, Church FC. Serpin-glycosaminoglycan interactions. Methods Enzymol. 2011;501:105–37. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385950-1.00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Chuang YJ, Swanson R, Li J, Seo K, Leung L, Lau LF, Olson ST. Antiangiogenic antithrombin down-regulates the expression of the proangiogenic heparan sulfate proteoglycan, perlecan, in endothelial cells. Blood. 2004;103:1185–91. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Swanson R, Izaguirre G, Xiong Y, Lau LF, Olson ST. The heparin-binding site of antithrombin is crucial for antiangiogenic activity. Blood. 2005;106:1621–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizutani A, Okajima K, Uchiba M, Isobe H, Harada N, Mizutani S, Noguchi T. Antithrombin reduces ischemia/reperfusion-induced renal injury in rats by inhibiting leukocyte activation through promotion of prostacyclin production. Blood. 2003;101:3029–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunzendorfer S, Kaneider N, Rabensteiner A, Meiehofer C, Reinisch C, Romisch J, Wiedermann CJ. Cell-surface heparin sulfate proteoglycan-mediated regulation of human neutrophil migration by the serpin antithrombin III. Blood. 2001;97:1079–85. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.4.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minnema MC, Chang ACK, Jansen PM, Lubbers YTP, Pratt BM, Whittaker BG, Taylor FB, Hack CE, Friedman B. Recombinant human antithrombin III improves survival and attenuates inflammatory responses in baboons lethally challenged with Escherichia coli. Blood. 2000;95:1117–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang W, Chuang YJ, Jin T, Swanson R, Xiong Y, Leung L, Olson ST. Antiangiogenic antithrombin induces global changes in the gene expression profile of endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5047–55. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shworak NW, Kobayashi T, De Agostini A, Smits NC. Anticoagulant heparan sulfate: To not clot-or not? Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2010;93:153–78. doi: 10.1016/S1877-1173(10)93008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harada N, Okajima K, Kushimoto S, Isobe H, Tanaka K. Antithrombin reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury of rat liver by increasing the hepatic level of prostacyclin. Blood. 1999;93:157–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiedermann CJ, Hofmann JN, Juers M, Ostermann H, Kienast J, Briegel J, Strauss R, Keinecke H-O, Warren BL, Opal SM for the KyberSept Investigators. High-dose antithrombin III in the treatment of severe sepsis in patients with a high risk of death: Efficacy and safety. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:285–92. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000194731.08896.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rezaie AR, Yang L. Probing the molecular basis of factor Xa specificity by mutagenesis of the serpin, antithrombin. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2001;1528:167–76. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rezaie AR. Heparin chain-length dependence of factor Xa inhibition by antithrombin in plasma. Thromb Res. 2006;119:481–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller EJ, Li J, Leng L, McDonald C, Atsumi T, Bucala R, Young LH. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor stimulates AMP-activated protein kinase in the ischaemic heart. Nature. 2008;451:578–82. doi: 10.1038/nature06504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Yang L, Rezaie AR, Li J. Activated protein C protects against myocardial ischemic/reperfusion injury through AMP-activated protein kinase signaling. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1308–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costa R, Morrison A, Wang J, Manithody C, Li J, Rezaie AR. Activated protein C modulates cardiac metabolism and augments autophagy in the ischemic heart. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:1736–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bae JS, Rezaie AR. Mutagenesis studies toward understanding the intracellular signaling mechanism of antithrombin. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:803–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rezaie AR. Prothrombin protects factor Xa in the prothrombinase complex from inhibition by the heparin-antithrombin complex. Blood. 2001;97:2308–13. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.8.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang L, Manithody C, Qureshi SH, Rezaie AR. Contribution of exosite occupancy by heparin to the regulation of coagulation proteases by antithrombin. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:277–83. doi: 10.1160/TH09-08-0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawano S, Kubota T, Monden Y, Tsutsumi T, Inoue T, Kawamura N, Tsutsui H, Sunagawa K. Blockade of NF-kappaB improves cardiac function and survival after myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1337–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01175.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown MA, Jones WK. NF-kappaB action in sepsis: the innate immune system and the heart. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1201–17. doi: 10.2741/1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Shepherd EG, Nelin LD. MAPK phosphatases--regulating the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:202–12. doi: 10.1038/nri2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonough JL, Van Eyk JE. Developing the next generation of cardiac markers: disease-induced modifications of troponin I. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2004;47:207–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howie-Esquivel J, White M. Biomarkers in acute cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23:124–31. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000305072.49613.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffmann JN, Mühlbayer D, Jochum M, Inthorn D. Effect of long-term and high-dose antithrombin supplementation on coagulation and fibrinolysis in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1851–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000139691.54108.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]