Abstract

Streptococcus agalactiae (SA) is a Group B Streptococcus, which is a common pathogen implicated in neonatal and geriatric sepsis. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis (EBE) is a condition that results from haematogenous seeding of the globe, during transient or persistent bacteremia. We document a case of a non-septic geriatric patient, who developed EBE after a transient bacteraemia with SA.

Background

Our patient's unusual presentation, and eventual outcome, contains useful guidance for other practitioners involved in the care of other patients with Streptococcus agalactiae (SA) endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis (EBE). A single positive blood culture, even in an asymptomatic patient, may be significant. Despite SA not being commonly thought of as a typical pathogenic organism in acute postoperative endophthalmitis, it may play an increasing role in geriatric patients with EBE.

Patients experiencing any change in visual functioning in the setting of a positive blood culture, require urgent ophthalmic consultation. Prompt medical and surgical intervention in patients with endogenous endophthalmitis can salvage the globe, and lead to better visual outcomes.

Case presentation

A 81-year-old woman presented to our emergency room with back pain and symptomatic urinary retention. Her medical history was significant for hypertension, osteoporosis and spinal stenosis. The patient's ocular history was significant for uneventful bilateral cataract extraction performed years earlier, via phacoemulsification with ‘in the bag’ placement of posterior chamber lenses. On admission, she was afebrile with stable vital signs. The patient was admitted to the hospital for a workup of possible complications from her spinal stenosis versus infectious causes of her urinary retention associated with back pain. On admission, neuroimaging studies of the spine were obtained, as were blood and urine cultures. At 48 h into the admission, urine cultures were positive for Escherichia coli and sensitive to ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone; blood cultures were positive for SA and were sensitive to all tested antibiotics. An infectious disease consultation was obtained for the documented bacteraemia and co-existing urinary tract infection, in a stable afebrile patient with no symptoms of cystitis. As per the consultant, confirmatory urine and blood cultures were obtained, and intravenous vancomycin therapy was initiated pending the results of the repeat cultures. At about 72 h after her admission, the patient complained of loss of vision in the right eye, with associated redness (figure 1). The ophthalmology service was consulted.

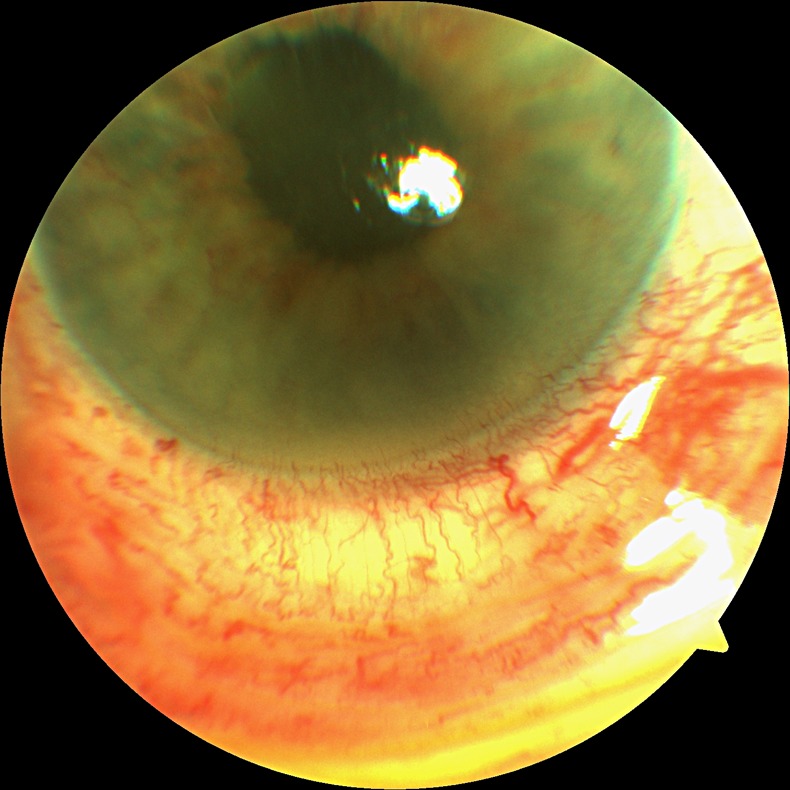

Figure 1.

External photo.

Ophthalmic examination revealed a best corrected visual acuity of 20/400 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left. There was no afferent pupillary defect, and there was full ocular motility. Applanation tonometer measurements were 12 and 13 mm Hg. Slit lamp examination was significant for 3+ cells and flare along with a 1 mm layered hypopyon in the right eye. Well-placed posterior chamber intraocular lenses were present bilaterally. Dilated funduscopic examination demonstrated dense vitritis on the right side obscuring retinal detail, while the left eye was within normal limits. B-scan ultrasonography performed on the right eye confirmed the presence of vitrits and the absence of a retinal detachment.

A clinical diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis secondary to SA was made. A bedside vitreous tap was performed, and sent for culture, and intravitreal vancomycin 1 mg/0.1 cc was injected. Topical fortified vancomycin 50 mg/1 cc was initiated four times a day. Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiogram was performed, and failed to reveal the presence of endocarditis as a potential source of the bacteraemia. Two days after the vitreous tap and intravitreal injection of vancomycin, the patient's visual acuity decreased to hand motions. Ophthalmic examination at this time demonstrated a completely fibrinous anterior chamber, along with 4+ vitritis. B scan demonstrated a very dense vitritis with inferior retinal traction. Previously obtained vitreous cultures from the initial vitreous tap demonstrated no growth. The decision was made to proceed with emergent Pars Plana Vitrectomy (PPV) for the worsening endophthalmitis. In the OR, undiluted vitreous for culture was obtained and a PPV was performed. Additionally, anterior chamber tap and washout were performed. Intra-operatively, the inferior 120° of retina was found to be necrotic. Endophotocoagulation was applied and air fluid exchange was performed. Vancomycin 1 mg/0.1 cc, amikacin 400 μg/0.1 cc and amphotericin 5 μg/0.1 cc were injected empirically, as all of the repeated blood and urine cultures demonstrated no growth.

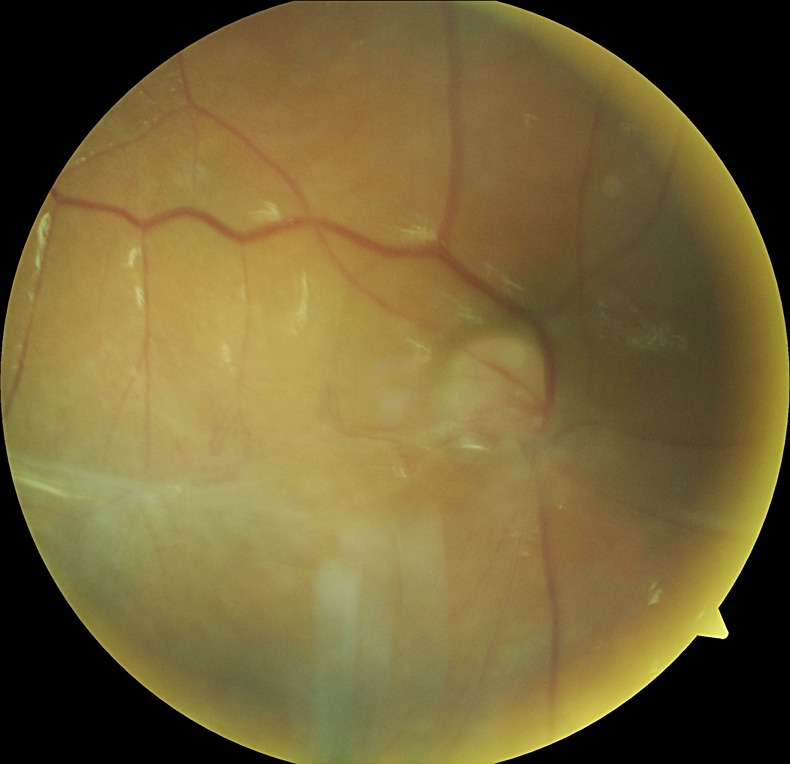

After the PPV with intravitreal injection of antibiotic and air tamponade, there was an immediate reduction in intraocular inflammation, with an anatomically reattached retina (figure 2). Prednisolone 1% and moxifloxacin were administered topically. On day 3 postvitrectomy, the vitreous cultures were positive for growth of SA, with similar susceptibility to the original blood isolate. Over the next week, there was complete clearing of the inflammation and a return of visual acuity of 20/200. Comprehensive systemic evaluations (including dental, podiatric and dermatological consultations) failed to locate the source of the bacteraemia. The patient was then discharged from the hospital.

Figure 2.

Post vitrectomy view of the fundus.

While the patient remained free of any evidence of endophthalmitis, she did develop a late onset retinal detachment. This detachment was repaired, and a silicone oil tamponade was utilised. The patient has remained free of ophthalmic inflammation now for 1 year with her latest visual acuity counting fingers.

Treatment

PPV with intravitreal injections of antibiotics.

Discussion

EBE is a relatively uncommon entity, representing a small subset of all cases of endophthalmitis, with Group B streptococci (GBS), accounting for less than 2–6% of all cases.1 Treatment for endogenous endophthalmitis remains controversial. The endopthalmitis vitrectomy study is the gold standard for the treatment of acute postoperative endophthalmitis. Its conclusions cannot be directly applied to EBE, as it is a different entity, with a different aetiology and presentation. As such, treatment for EBE is typically individualised to the patient's presentation. Outcomes in EBE are typically dependent on the virulence of the organism, and how rapidly the intervention can be initiated.2 Many patients with EBE, are quite ill, and can be obtunded or ventilator dependent, and may not be able to complain of visual changes, hence delaying the diagnosis and contributing to a delay in intervention. In our case, the patient was able to report an immediate change in visual acuity, allowing us to intervene relatively early in the disease process. We were able to reduce the infectious and inflammatory burden with vitrectomy, and utilised empiric broad spectrum antibiotics at the time of vitrectomy allowing us to eradicate the infection.3

Attention should be paid to the possibility of the patient developing endogenous GBS endophthalmitis. The incidence of GBS bacteraemia is increasing due to an aging population that is frequently afflicted with one or more chronic underlying conditions.4 5

Our case highlights the need for a high index of suspicion for EBE in the setting of a transient Gram-positive bacteraemia, even if the blood culture results are presumed to be a contaminant. Aggressive pharmacological and surgical treatment may be required in these cases to minimise visual loss.

Learning points.

A high index of suspicion and vigilance is required for diagnosing endogenous endophthalmitis in non-communicative patients.

In cases of endogenous endophthalmitis, early and aggressive intervention from ophthalmology is required to minimise vision loss.

Blood cultures that are positive for atypical organisms can be pathologic and not contaminants.

Streptococcus agalactiae and other Group B streptococci can cause severe ocular disease in the adult population.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Gupta S, Agnani S, Tehrani S, et al. Endogenous Streptococcus agalactiae endophthalmitis as a presenting sign of precursor T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. Arch of Oph 2010;2013:384–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study Group Results of the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study: a randomized trial of immediate vitrectomy and of intravenous antibiotics for the treatment of postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;2013:1479–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pokharel D, Doan AP, Lee AG. Group B streptococcus endogenous endophthalmitis presenting as septic arthritis and a homonymous hemianopsia due to embolic stroke. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;2013:300–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards MS, Baker CJ. Group B streptococcal infections in elderly adults. Clin Infect Dis 2005;2013:839–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durand ML. Bacterial endophthalmitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2009;2013:283–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]