Abstract

Dentin dysplasia type I is a rare hereditary disturbance of dentin formation characterised clinically by nearly normal appearing crowns and hypermobility of teeth that affects one in every 100 000 individuals and manifests in both primary and permanent dentitions. Radiographic analysis shows obliteration of all pulp chambers, short, blunted, and malformed roots, and periapical radiolucencies of non-carious teeth. This paper presents three cases demonstrating classic features of type I dentin dysplasia.

Background

Dentin dysplasia (DD) is a rare defect of dentin development with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, which may present with either mobile teeth or pain associated with spontaneous dental abscesses or cysts.1 This condition was first described by Ballschmiede2 but it was Rushton3 who termed the condition dentinal dysplasia. It affects approximately one patient in every 100 000.4 5 Shields et al6 proposed a classification that divided dentin dysplasia into two main classes based on the clinical and radiographic appearance: type I (DD1), ‘dentin dysplasia,’ and type II (DD2), ‘anomalous dysplasia of dentin’. Subsequently, DD1 started being referred to as ‘radicular dentin dysplasia’ and DD2 as ‘coronal dentin dysplasia’, in order to indicate the parts of the teeth that are primarily involved. A third type of dentin dysplasia or focal odontoblastic dysplasia, with radiographic aspects of both types of dysplasia, has also been described. DD1 is characterised clinically by nearly normal appearing crowns and hypermobility of the teeth.7

In type I, both the deciduous and permanent dentitions are affected. The crowns of the teeth appear clinically normal in morphology but defects in dentin formation and pulp obliteration are present. There are four subtypes for this abnormality. In type 1a, there is no pulp chamber and root formation, and there are frequent periradicular radiolucencies; type 1b has a single small horizontally oriented and crescent shaped pulp, and roots are only a few millimetres in length and there are frequent periapical radiolucencies; in type 1c, there are two horizontal or vertical and crescent shaped pulpal remnants surrounding a central island of dentine and with significant but shortened root length and variable periapical radiolucencies; in type 1d, there is a visible pulp chamber and canal with near-normal root length, and large pulp stones that are located in the coronal portion of the canal and create a localised bulging in the canal, as well as root constriction of the pulp canal apical to the stone and few peri-apical radiolucencies.8 Histologically, the enamel and the immediately subjacent dentin appear normal. Deeper layers of dentin show an atypical tubular pattern with an amorphous, atubular area and irregular organisation. Pulpally to normal appearing mantle dentin and globular or nodular masses of abnormal dentin are seen. It is not known if DD type I is another allelic disorder of the dentin sialophosphoprotein gene or a mixed phenotype.1 This article describes three cases of DD type I, subtype 1a, highlighting the clinical and radiographic features of the defect.

Case presentation

Case I

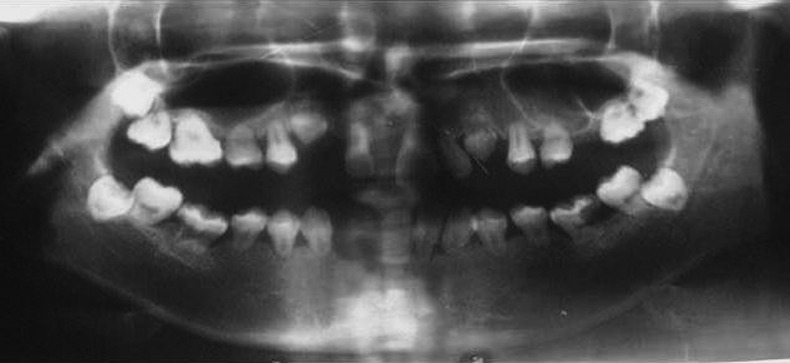

A 16-year-old female patient presented with loose teeth and asking for prosthetic treatment. The girl's mother also had the same history. The patient had lost several teeth, resulting in discomfort in mastication and aesthetic problems. The patient's medical history revealed no evidence of disturbance in general health. Extraoral examination showed an abnormal facial appearance, with a dished profile resulting from the loss of numerous teeth. Intraoral examination (figure 1) disclosed presence of 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 21, 22, partially erupted 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47. Mobility of the teeth was present with, 14, 15, 17, 21, 22, 24, 25, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 and 44, 45; 15 and 25 were slightly rotated. Both side maxillary permanent second premolars were slightly rotated. Panoramic radiographic examination (figure 2) showed all the teeth to have short, blunted and malformed roots. Pulp chambers in maximum teeth were completely obliterated. Treatment strategy consisted of instructing the patient in oral hygiene and provision of treatment to restore occlusion, enhance mastication and improve aesthetics.

Figure 1.

Case I: Intraoral photograph.

Figure 2.

Case I: OPG.

Case II

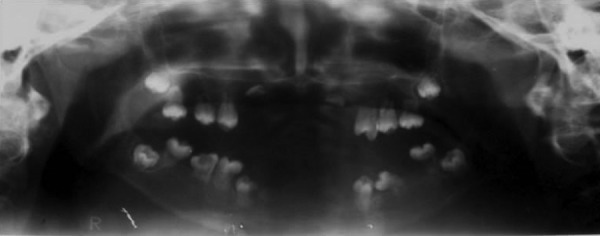

An 11-year-old female patient presented with several missing teeth. Medical history of the patient was not significant. Intraoral examination (figure 3) of the patient revealed 14, 15, 16, 24, 25, 26, 36, 45, 46, 47. The teeth present in the oral cavity had abnormal occlusal morphology. These teeth were free of carious lesions. Clinical examination revealed no changes in the soft tissue. A panoramic radiograph (figure 4) revealed all teeth to have short, blunted and malformed roots. Although the patient had reached age 10, her maxillary and mandibular incisors and first premolars were not present. Complete obliteration of pulp chambers was noted in both erupted and developing teeth. A treatment plan was developed with the aim of preserving existing teeth, and enhancing occlusion, mastication and aesthetics.

Figure 3.

Case II: Intraoral photograph.

Figure 4.

Case II: OPG.

Case III

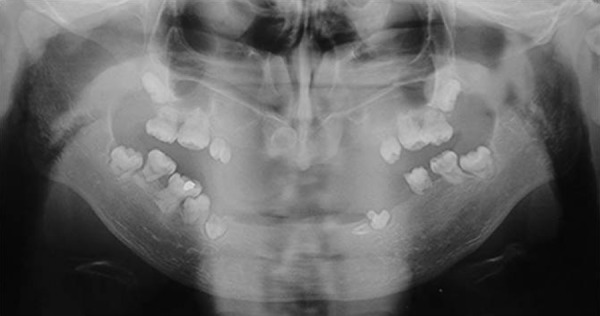

A 15-year-old male patient presented with multiple missing teeth. The patient gave a history of tooth exfoliation on its own. The patient's sister and grandfather also had similar problems. On intraoral examination (figure 5), multiple teeth were missing. The missing teeth were 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45. Erupted teeth showed multiple cusps. On radiographic examination, OPG showed bulbous crown with cervical constriction and short roots with multiple missing teeth (figure 6). A treatment plan was developed with the aim of preserving existing teeth, and enhancing occlusion, mastication and aesthetics.

Figure 5.

Case III: Intraoral photograph.

Figure 6.

Case III: OPG.

Investigations

Routine haemogram was done, which was not significant.

Differential diagnosis

Radiation induced tooth changes

Dentinogenesis imperfecta

Radiation induced tooth changes while the teeth are developing can manifest in any form such as altered morphology of crown, shortness and tapering of roots. Both dentin dysplasia and dentinogenesis imperfecta have a crown with altered colour and occluded pulp chamber. Thistle tube shaped pulp chamber in single rooted tooth is a feature of dentin dysplasia type I. Bulbous shaped crowns with constriction in cervical region present in dentin dysplasia while crowns have normal shape, size and proportion in dentinogenesis imperfect. Roots are long and narrow with dentinogenesis imperfecta and normal appearing roots or practically no roots are a feature of dentin dysplasia type I.

Treatment

A treatment plan was developed with the aim of preserving existing teeth, and enhancing occlusion, mastication and aesthetics for these patients.

Outcome and follow-up

The patients were kept under follow-up and were treated for the complaints regarding mastication, aesthetics and occlusion.

Discussion

Little is known about the aetiology of DD. Several factors have been implicated as possible causes, but the precise nature of the defect has not yet been determined. Dentin contains type I and type II collagen, the abnormality of which is presented as dentine dysplasia of different forms and severity.

The pathogenesis of DD is still unknown in the dental literature. Logan et al9 proposed that it is the dentinal papilla that is responsible for the abnormalities in root development. They suggested that multiple degenerative foci within the papilla become calcified, leading to reduced growth and final obliteration of the pulp space. Wesley et al10 proposed that the condition is caused by an abnormal interaction of odontoblasts with ameloblasts leading to abnormal differentiation and/or function of these odontoblasts. Dentin dysplasia type I should be differentiated from dentin dysplasia type II, dentinogenesis imperfecta and odontodysplasia. In our patients, the calcified pulp chambers and rootless teeth are characteristic findings for the diagnosis of DD type 1, subtype 1c. DD is usually an autosomal dominant condition, and in two of our patients, there was a familial history of the disease, and the patient with no family history is considered to be a first generation sufferer. Teeth with radiographic or histological features of DD occur in a number of disorders such as Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and the brachioskeletogenital syndrome.11 There are reports that have suggested possible variations in the morphology of teeth affected by this type of dysplasia which was seen in our patients.12 13 Although malocclusion is not a specific feature of DD1, a few cases of malocclusion have been reported in association with this disorder.13

There is no specific treatment for this rare genetic disorder affecting the dentin development of the teeth. Only procedures to avoid the premature loss of hyper-mobile teeth and to stimulate the normal development of the occlusion can be undertaken because the affected teeth have a very unfavourable prognosis due to the short roots and presence of associated periapical radiolucencies. If necessary, space loss due to spontaneous exfoliation of hyper-mobile teeth can be avoided by the placement of removable space maintainers or orthodontic appliances early diagnosis and continuous follow-up of cases.14

Learning points.

Early diagnosis of the condition is important for initiation of effective preventive treatment.

A preventive approach should be taken in patient management by avoidance of periodontal disease and dental caries which is the best possible way to maintain the dentition for an increased period of time.

In teeth with shorter roots, such as those seen in the above cases, the abnormal ramifications of the vascular pulp channels make complete obturation impossible.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Toomarian L, Mashhadiabbas F, Mirkarimi M, et al. Dentin dysplasia type I: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 2010;2013:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballschmiede G. Dissertation, Berlin, 1920. In: Herbst E, Apffelstaedt M. Malformations of the jaws and teeth. New York: Oxford University Press, 1930:286 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rushton MA. A case of dentinal dysplasia. Guy's Hosp Rep 1939;2013:369–73 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansari G, Reid JS. Dentinal dysplasia type I: review of the literature and report of a family. ASDC J Dent Child 1997;2013:429–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witkop CJ., Jr Hereditary defects of dentin. Dent Clin North Am 1975;2013:25–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shields ED, Bixler D, el-Kafrawy AM, et al. A proposed classification for heritable human dentine defects with a description of a new entity. Arch Oral Biol 1973;2013:543–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rocha CT, Nelson-Filho P, Bezerra da Silva LA, et al. Variation of dentin dysplasia type I: report of atypical findings in the permanent dentition. Braz Dent J 2011;2013:74–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neville B, Damm D, Allen C, et al. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 3rd edn. Elsevier, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Logan J, Becks H, Silverman S, et al. Dentinal dysplasia. Oral Surg 1962;2013:317–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wesley RK, Wysocki GP, Mintz SM, et al. Dentin dysplasia type I. Oral Surg 1976;2013:516–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perl T, Farman AG, Elizabeth P, et al. Radicular (Type I) dentin dysplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1977;2013:746–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elzay RP, Robinson CT. Dentinal dysplasia, report of a case. Oral Surg 1967;2013:338–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.OZer L, Karasu H, Aras K, et al. Dentin dysplasia type I: report of atypical cases in the permanent and mixed dentitions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2004;2013:85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shankly PE, Mackie IC, Sloan P. Dentin dysplasia type I: report of a case. Int J Pediatr Dent 1999;2013:37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]