Abstract

Small cell gall bladder carcinoma (Scc-GB) is a very rare entity. Although some cases present with endocrine manifestations, paraneoplastic hyponatraemia has been reported in only one previous case. Recently, the antidiuretic hormone (ADH) receptor antagonist mozavaptan has become available. Herein we report a case with Scc-GB complicated with syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) treated with mozavaptan. A 47-year-old woman was referred to our hospital for hyponatraemia. Physical examination revealed elevated serum ADH, a gall bladder mass. She was clinically diagnosed with Scc-GB with SIADH as a paraneoplastic syndrome. Mozavaptan was used for SIADH. Serum sodium was quickly normalised after mozavaptan treatment. Two months later, metastasis to the subcutis of the abdominal wall was observed. The metastatic nodule was resected, and small cell carcinoma (Scc) was identified pathologically. Mozavaptan was effective for improvement of hyponatraemia in this patient with Scc-GB complicated with SIADH.

Background

Small cell gall bladder carcinoma (Scc-GB) is a very rare entity, with fewer than 100 cases reported in the literature. Scc-GB accounts for 1–5% of all gall bladder cancers.1 2 Scc-GB cases complicated with syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) are even rarer. Paraneoplastic SIADH is an ectopic antidiuretic hormone (ADH) syndrome induced by the abnormal secretion of ADH by cancer cells. As hyponatremia caused by SIADH leads to central nervous system symptoms, SIADH is a medical emergency. SIADH is conventionally treated with water restriction and sodium replacement; however, these treatments diminish quality of life (QOL). Paraneoplastic SIADH can be improved by cancer volume reduction; however, cisplatin therapy causes hyponatraemia by renal salt wasting.3 Thus, hypernatraemia control is very important for QOL as well as for administration of chemotherapy. Recently, in 2006, the ADH receptor antagonist mozavaptan was approved as an orphan drug for the treatment of SIADH in Japan.4 In this report we present a case of Scc-GB complicated with SIADH that was treated with mozavaptan.

Case presentation

A 47-year-old, previously healthy woman was referred to our hospital for hyponatremia. She had a 3-month history of general fatigue. Laboratory examination revealed severe hyponatraemia (111 mmol/L; table 1). Serum osmolality was 219 mOsm/kg, with a urine osmolality of 543 mOsm/kg and urine sodium of 213 mmol/L. Thyroid function and adrenal cortex function were normal. Her serum ADH was 5.8 pg/mL (normal range, 0.3–3.5 pg/ml). Laboratory findings indicated SIADH as the source of hyponatremia. Physical examination revealed an abdominal mass in the right upper quadrant. Abdominal ultrasonography and CT revealed gall bladder tumour and abdominal lymphadenopathy (figure 1A,B). CT scan of her thorax did not show any pulmonary lesions, and no other masses were apparent on brain CT and MRI. Gall bladder cancer was highly suspected, so an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed, which revealed pancreaticobiliary maljunction and bile duct stenosis due to gall bladder carcinoma (figure 2).

Table 1.

Laboratory data on admission

| Complete blood count | Biochemistry (continued) | Endocrine tests |

|---|---|---|

| WBC: 4.600/μL | Ca: 8.2 mg/dL | TSH: 0.861 μIU/mL |

| RBC: 3.91×106/μL | P: 3.4 mg/dL | F-T3: 2.74 pg/dL |

| Hb: 10.0 g/dL | AST: 33 IU/L | F-T4: 0.91 ng/dL |

| Ht: 27.8% | ALT: 23 IU/L | ACTH: 12.2 pg/mL |

| Plt: 334×103/μL | LDH: 288 IU/L | Cortisol: 9.2 μg/dL |

| Biochemistry | ALP: 183 IU/L | Aldosterone: 6.7 ng/dL |

| TP: 6.4 g/dL | γGTP: 26 IU/L | Renin: 0.2 ng/mL |

| Alb: 3.4 g/dL | CRP: 0.0 mg/dL | ADH: 5.8 pg/mL |

| T-Bil: 0.7 mg/dL | HbA1c: 5.4% | Tumour markers |

| UN: 5 mg/dL | Osmolality: 219 mOsm/kg | CA19-9: 73 U/mL |

| Cr: 0.3 mg/dL | Coagulation | CEA: 3.6 U/mL |

| UA: 0.9 mg/dL | APTT: 34.0 s | Urine |

| T-Cho: 132 mg/dL | PT: 82.9% | Na: 213 mmol/L |

| Na: 111 mEq/L | Infection | K: 9.4 mmol/L |

| K: 4.2 mEq/L | HCV Ab: (−) | Osmolality: 543 mOsm/kg |

| Cl: 82 mEq/L | HBs Ag: (−) |

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; ADH, antidiuretic hormone; Alb, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen; Cr, creatinine; CRP, C reactive protein; F-T3, free triiodothyronine; F-T4, free thyroxine; Hb, haemoglobin; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c; HBs Ag, hepatitis B antigen; HCV Ab, hepatitis C antibody; Ht, haematocrit; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; Plt, platelet count; PT, prothrombin time; RBC, red blood cell count; T-Bil, total bilirubin; T-cho, total cholesterol; TP, total protein; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; UA, uric acid; UN, urea nitrogen; WBC, white cell count; γGTP, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; 19-9 CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

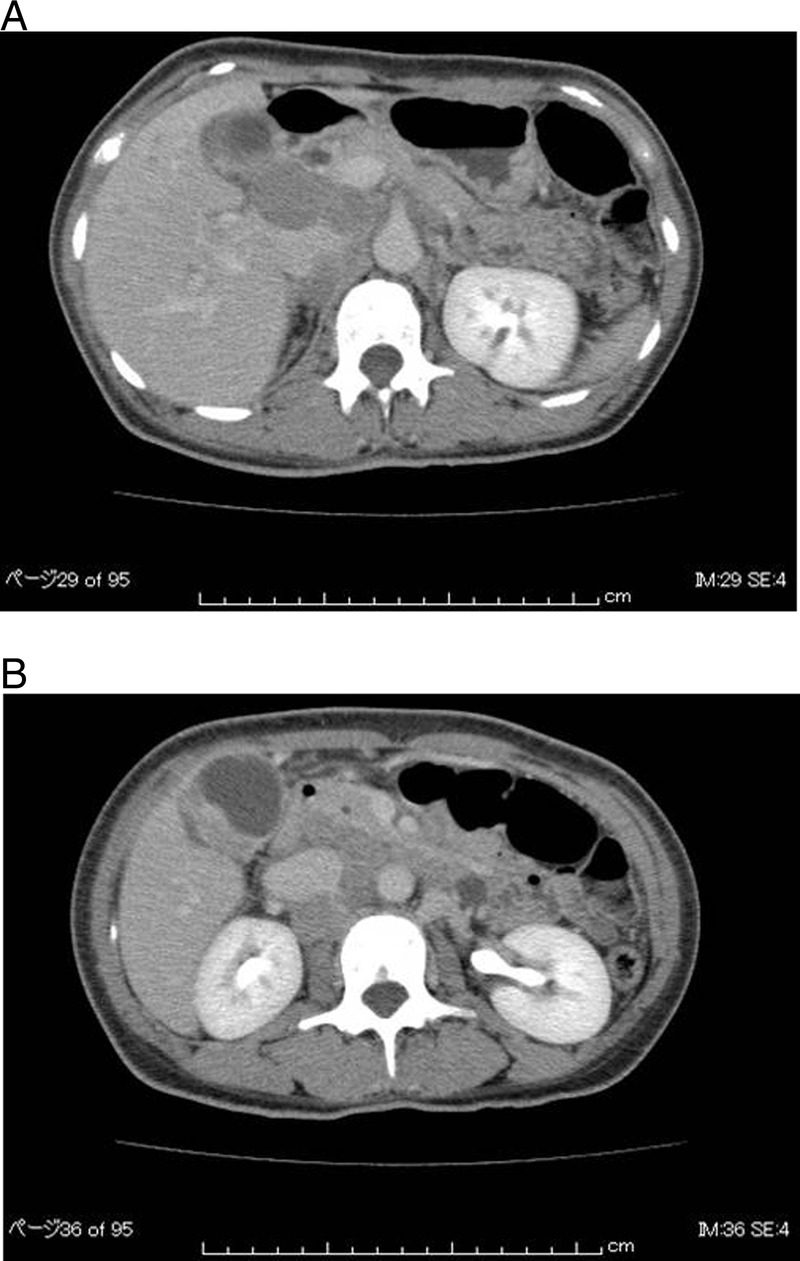

Figure 1.

(A and B) Abdominal CT on admission. Multiple areas of swelling in the lymph nodes (hypoenhancement lymph node) are seen around the portal vein. An enhanced mass can be seen in the fundus of the gall bladder.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography revealed pancreatobiliary malformation and hepatic duct stenosis. The gall bladder is not stained.

Bile duct cytology did not reveal carcinoma cells. Gall bladder cancer combined with SIADH is very rare; however, there was no evidence of other disease causing SIADH. We diagnosed gall bladder carcinoma combined with SIADH as a paraneoplastic syndrome.

Treatment

To treat the gall bladder carcinoma, chemotherapy (gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2) was initiated; however, due to grade 2 nausea (NCI CTCAE), the patient elected to discontinue chemotherapy. Instead, radiotherapy was started (total dose, 60 Gy). Immediately after diagnosis, she was started on sodium replacement (9 g/day) and fluid restriction (1 L/day). However, her serum sodium level remained near pretreatment levels, even after initiation of radiotherapy. Owing to the lack of response to hyponatremia treatment, we elected to administer mozavaptan 30 mg/day; this resulted in serum sodium level elevation. After stopping water restriction and sodium replacement therapy, her sodium concentration level was sustained in the normal range. After the completion of radiotherapy, CT revealed a marked reduction in the size of the gall bladder tumour—characterised as a partial response (PR) and near-complete response (CR)—and disappearance of abdominal lymphadenopathy (figure 3A,B). Her serum ADH level was slightly decreased (figure 4). To analyse the results of radiotherapy, mozavaptan was stopped; her serum sodium level remained within the normal range. Owing to the good response to radiotherapy and the presence of SIADH, we suspected her gall bladder carcinoma to be a neuroendocrine tumour. Consistent with this, her serum neuron-specific enolase level was elevated at 46.9 μg/mL (upper normal limit, 16.3 μg/mL). Two weeks after she was discharged, her sodium levels decreased to 120 mmol/l, so mozavaptan was reinitiated; her sodium concentration quickly normalised. At this time, an ∼10 mm nodule was found in the subcutis of the abdominal wall and was resected. Histology revealed small cells that were immunohistochemically positive for synaptophysin, chromogranin and CD56, and pathological analysis indicated Scc (figure 5A–D). Considering her recent history, we diagnosed metastatic Scc-GB combined with SIADH.

Figure 3.

(A and B) Abdominal CT after radiotherapy. A bile duct drain has been inserted. Lymphadenopathy has resolved, and the fundal mass is markedly decreased.

Figure 4.

Serum sodium (red) and antidiuretic hormone (ADH) (green) levels. The blue arrow indicates abdominal wall nodule resection. After radiotherapy (RTx), serum ADH was slightly decreased; after an abdominal nodule was noted, serum ADH was markedly elevated. Serum sodium and ADH levels may have paralleled the Scc-GB.

Figure 5.

Pathology of the abdominal wall mass. (A) H&E stain showing small round malignant cells consistent with small cell carcinoma. (B) Synaptophysin immunohistochemical stain. Synaptophysin-positive cells are observed in the tumour. (C) Chromogranin immunohistochemical stain. Chromogranin-positive cells are observed in the tumour. (D) CD56 immunohistochemical stain. CD56-positive cells are observed in the tumour. Based on these pathological results, this was diagnosed as small cell carcinoma metastasising to the subcutis.

Outcome and follow-up

Chemotherapy was planned; however, she did not consent to chemotherapy and wished to receive palliative care only. Four months after resection of the abdominal wall nodule, she died from Scc-GB.

Discussion

Scc primarily originates in the lung; extrapulmonary Scc is very rare, and Scc-GB is even rarer. Albores-Saavedra et al5 first described Scc-GB in 1981. Scc-GB represents 1% of extrapulmonary Scc cases,6 and Ultrasound surveillance, epidemiology and end results (SEER) data suggest that Scc-GB accounts for approximately 0.5% of all gall bladder cancers.1 This rare tumour has mainly been described in case reports; only 73 cases have been published in the English literature.7 As shown in table 2, the median age of patients with Scc-GB is 67 years (range, 25–86 years) and it is more common in women. The majority of patients (66%) are diagnosed with stage IV disease, with lymph nodes being the most common site of metastasis (70%). Median survival is only 9 months (range, 1–189 months). By histology, 72% of cases are pure Scc and 28% are combined Scc and adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma.7 The histogenesis of combined neuroendocrine cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma has been controversial. Three hypotheses have been proposed to describe this phenomenon: (1) the two components arise simultaneously from two different precursor cells, (2) one component produces the other and (3) a single totipotent progenitor cell produces both components; this latter hypothesis is currently supported by many investigators.8–11 Normally, no neuroendocrine cells are present in the gall bladder. They may be present in the intestinal or gastric metaplastic gall bladder mucosa, secondary to cholelithiasis and chronic cholecystitis. Such chronic inflammation leads to metaplastic changes and tumorigenesis. In this way, neuroendocrine gene expression may be activated, leading to neuroendocrine tumorigenesis. Mahipal et al reported that Scc-GB is divided into two subtypes: (1) tumours that consist only of Scc and (2) tumours that are mixed Scc and adenocarcinoma (table 2). The two components may be present at the same time; however, as the Scc component rapidly grows, the adenocarcinoma component disappears, resulting in the formation of pure Scc. Thus, one subtype emerges from two because of differences in growth rather than biological characteristics. In the present case, we diagnosed resected nodule, hence could not determine whether pure Scc or mixed. However we could tell that pancreaticobiliary maljunction was demonstrated by ERCP; this may have been the cause of tumorigenesis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with small cell carcinoma of the gall bladder*

| Number of patients | 74 |

| Clinical cases | 55 |

| Autopsy cases | 19 |

| Median age (range) in years (n=73) | 67 (25–86) |

| Sex (n=74) | |

| Men | 25 (34%) |

| Women | 49 (66%) |

| Histology (n=57) | |

| Pure small cell carcinoma | 41 (72%) |

| Combined | 16 (28%) |

| Cholelithiasis (n=73) | 50 (68%) |

| Stage (n=71) | |

| I–III | 24 (34%) |

| IV | 47 (66%) |

| Metastases | |

| Lymph nodes (n=71) | 50 (70%) |

| Liver (n=70) | 45 (64%) |

| Lung (n=70) | 7 (10%) |

| Surgery (n=43) | 40 (93%) |

| Chemotherapy (n=43) | 20 (47%) |

| Median survival (range), months | 9 (1–189) |

*n, number of patients for whom data were available for the particular characteristic.

Source: Copied from Mahial et al.7

Gall bladder carcinoma has been associated with various paraneoplastic syndromes, including hypercalcaemia, acanthosis nigricans, dermatomyositis, sensory neuropathy, opsoclonus and Cushing's syndrome.12–20 However, only one case with hyponatremia as a paraneoplastic syndrome has been previously reported2,1; this was a case of Scc-GB. In the present case, serum osmolality was 219 mOsm/kg (normal range, 275–300 mOsm/kg). However, despite hypo-osmolality, serum ADH was 5.8 pg/mL (normal range, 0.3–3.5 pg/mL) and other endocrine test values were normal. Laboratory results indicated SIADH, and gall bladder carcinoma appeared to be the only other abnormality; thus, we diagnosed SIADH combined with gall bladder cancer. This case experienced hyponatremia as the first symptom. Paraneoplastic SIADH has been reported to cause severe hyponatraemia and lead to life-threatening neurological complications.2,2 Thus, treatment of SIADH is very important. However, SIADH treatment requires severe water restriction, which in addition to worsening QOL prevents administration of certain chemotherapy regimens, particularly those containing platinum agents. In the present case, immediately after diagnosis, she was started on sodium replacement (9 g/day) and fluid restriction (1 L/day). However, her serum sodium level remained near pretreatment levels, even after initiation of radiotherapy. SIADH in pulmonary Scc is usually associated with inappropriate elevation of ADH and can be resolved promptly (<3 weeks) following initiation of combination chemotherapy.2,3 In the present case, chemotherapy could not be continued due to adverse effects, so radiotherapy was initiated. We did not think it would be possible to sustain the patient's sodium levels during radiotherapy by conventional treatment, so we elected to use mozavaptan to treat SIADH. Mozavaptan is the world's first non-peptide V2R antagonist with aquaretic action. In a Japanese study,4 serum sodium was increased to 6 mmol/L in 12 out of 16 patients within 24 h of mozavaptan administration. In the present case, mozavaptan quickly improved the serum sodium level, eliminating the need for severe water restriction; thus, this treatment effectively maintained the patient's QOL. The patient responded to radiotherapy, and mozavaptan was stopped. However, 2 weeks later, her serum sodium again decreased. At the time radiotherapy was stopped, both abdominal lymphadenopathy and gall bladder tumour had decreased dramatically. However, SIADH could not be resolved, and mozavaptan was started again. In the case of Nq et al,2,1 low sodium was persistent, despite chemotherapy. This may reflect a difference between pulmonary Scc and Scc-GB.

The patient eventually died due to Scc-GB. However, mozavaptan played a key role in the treatment of her SIADH, eliminating the need for severe water restriction and sodium replacement. Thus, mozavaptan can improve QOL in such patients.

Learning points.

Gall bladder small cell carcinoma.

Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone.

Mozavaptan.

Footnotes

Contributors: TT and KT analysed and interpreted the data; drafted the article; critically revised the article for important intellectual content; and final approval of the article. TT and KT were involved in provision of study materials or patients.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Henson DE, Albores-Saavedra J, Corle D. Carcinoma of the gallbladder: histologic types, stage of disease, grade, and survival rates. Cancer 1992;2013:1493–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iype S, Mirza TA, Propper DJ, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of the gallbladder. Three cases and a review of the literature. Postgrad Med J 2009;2013:213–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao L, Prashant J, Sumoza D. Renal salt wasting in a patient with cisplatin-induced hyponatremia. Am J Clin Oncol 2002;2013:344–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaguchi K, Shijubo N, Kodama T, et al. ; Ectopic ADH Syndrome Therapeutic Research Group. Clinical implication of the antidiuretic hormone (ADH) receptor antagonist mozavaptan hydrochloride in patients with ectopic ADH syndrome. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2011;2013:148–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albores-Saavedra J, Cruz-Ortiz H, Alcantara-Vazques A, et al. Unusual types of gallbladder carcinoma. A report of 16 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1981;2013:287–93 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galanis E, Frytak S, Lloyd RV. Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. Cancer 1997;2013:1729–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahipal A, Gupta S. Small-cell carcinoma of the gallbladder: report of a case and literature review. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2011;2013:135–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noda M, Miwa A, Kitagawa M. Carcinoid tumors of the gallbladder with adenocarcinomatous differentiation :a morphologic and immunohistochemical study. Am J Gastroenterol 1989;2013:953–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox WF, Jr, Pierce GB. The endodermal origin of the endocrine cells of an adenocarcinoma of the colon of the rat. Cancer 1982;2013:1530–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wada A, Ishigro S, Tateishi R, et al. Carcinoid tumor of the gallbladder associated with adenocarcinoma. Cancer 1983;2013:1911–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu T, Tajiri T, Akimaru K, et al. Combined neuroendocrine cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the gall bladder: report of a case. J Nippon Med Sch 2006;2013:101–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimazaki A, Shiozawa S, Kim DH, et al. A case of small cell carcinoma of the gallbladder. J Jpn Coll Surg 2009;2013:927–32 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng ES, Venkateswaran K, Ganpathi SI, et al. Small cell carcinoma complicated by paraneoplastic hyponatremia: a case report and literature review. J Gastrointest Cancer 2010;2013:264–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe Y, Ogino Y, Ubukata E, et al. A case of a gallbladder cancer with marked hypercalcemia and leukocytosis. Jpn J Med 1989;2013:722–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi M, Fujiwara M, Kishi K, et al. CSF producing gallbladder cancer: case report and characteristics of the CSF produced by tumor cells. Int J Cell Cloning 1985;2013:294–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imoto Y, Muguruma N, Kimura T, et al. A case of parathyroid hormone-related peptide producing gallbladder carcinoma presenting humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi 2007;2013:401–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villababona CM, Esteve M, Vidaller A, et al. Hypercalcemic crisis gallbladder cancer. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 1986;2013:532–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawashima T, Ishida K, Yamamura H, et al. Gallbladder cancer with hypercalcemic crisis. Nippon Rinsho 1971;2013:1433–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spence RW, Burns-Cox CJ. ACTH-secreting ‘apudoma’ of gallbladder. Gut 1975;2013:473–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albores-Saavedra J, Molberg K, Henson DE. Unusual malignant epithelial tumors of the gallbladder. Semin Diagn Pathol 1996;2013:326–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nq ES, Venkateswaran K, Ganpathi SI, et al. Small cell gallbladder carcinoma complicated by paraneoplastic hyponatremia: a case report and literature review. J Gastrointest Canc 2010;2013:264–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arieff A, Llach F, Massey SG. Neurological manifestations and morbidity of hyponatremia correlation with brain water and electrolytes. Medicine 1976;2013:121–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.List AF, Hainsworth JD, Davis BW, et al. The syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) in small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1986;2013:1191–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]