Abstract

The concept of personhood is critical to the provision of holistic, patient-centred, palliative care yet no common definition of this term exists. Some characterise personhood by the presence of consciousness-related features such as self-awareness while others deem personhood present by virtue of Divine endowment or as a result of one's social relations. Efforts to appropriately delineate this concept come under scrutiny following suggestions that patients rendered deeply and irreversibly unconscious lack personhood and ought to be considered ‘dead’.

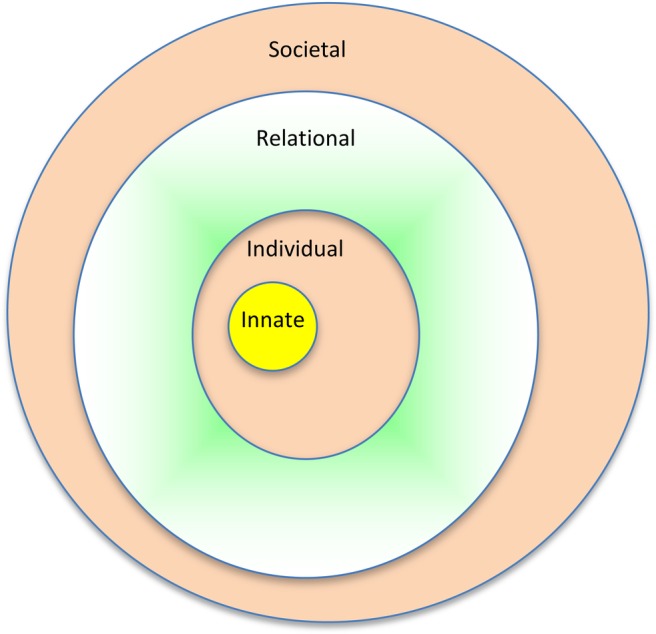

This case report studies the views of a family caring for a deeply sedated terminally ill patient, to appropriately site local views of personhood within the context of sedation at the end of life. The resultant Ring Theory of Personhood dispenses with concerns that personhood is solely dependent upon consciousness and distances sedative treatments of last resort such as continuous deep sedation from euthanasia.

Background

What makes you ‘you’ has variously been suggested to be dependent on the presence of self-awareness, the ability to ‘value one's own existence’, one's relational links or one's connections with the Divine.1–10 Yet despite its pivotal role in the understanding of how patients conceive their quality of life, dignity and the manner that they would wish to be cared for, no common understanding of this term prevails. Resolving this lack of clarity on clinically relevant conceptions of personhood becomes critical in light of suggestions that any treatment that intentionally terminates personhood through the negation of consciousness ought to be considered analogous to euthanasia.1–17

LiPuma9 explicates his position by stating that the induction of deep unconsciousness where no ‘minimum level of consciousness’ is retained and where there is no ‘potential for future conscious states’, irreversibly abolishes personhood. LiPuma argues further that existing in a state devoid of personhood and without any potential for regaining this feature as terminally ill patients administered sedative treatments till death such as continuous deep sedation (CSD) inevitably are, is indistinguishable from death.9 LiPuma states that the intentional suppression of consciousness that irreversibly negates personhood is indistinguishable from wilful acts of terminating life.9 LiPuma's position thus invites comparisons between CSD and the vexed practice of euthanasia.9

This position of placing conscious function at the fore of determinations of personhood is not exclusive to philosophers. It is not uncommon for local healthcare professionals to resist the employment of moderate sedation to ameliorate the symptoms of terminally ill patients for fear of negatively impacting the personhood of their patients. Practically, such a position creates a general resistance towards many palliative care interventions at the end of life, which extend far beyond considerations of CSD. The potential for suboptimal end of life care particularly in light of increasing publications on the ethical implications of sedatives use at the end of life motivates present efforts to appropriately characterise the personhood of deeply and irreversibly sedated local terminally ill patients.2 3 9

Clinical experience suggests that patients on palliative care view personhood in a manner more akin to Kitwood's18 and Buron's19 holistic conceptions of personhood. Kitwood's18 and Buron's19 conceptions of personhood envisage it to be a coadunation of transcendent, individual, social and relational considerations rather than being limited to the one-dimensional views proposed by LiPuma's9 consciousness-dependent, Nelson's1 Divinity-associated or Ho et al's20 relational derived concepts of personhood. Yet even Kitwood's18 and Buron's19 conceptions of personhood are still seen as ‘limited’ within the Singaporean society that regard personhood in a more interrelated and flexible manner.20

Though it shares some similarities with Schotman's and Jans's Personalist conception, which see personhood as ‘being directed towards each other’, local conceptions are neither religiously located nor see all individuals as equal within the eyes of the family and society.20–23 As a result, local conceptions require culturally appropriate, ethically relevant, clinical sensitive characterisation.

To crystallise local conceptions, this case report utilises analysis of observations made and discussions had with a family caring for a terminally ill member with metastatic bladder cancer to appropriately site conceptions of personhood within the local end of life context.

Case presentation

The patient was a 70-year-old doctor with extensive transitional cell bladder cancer that had not been amenable to multiple lines of chemotherapy. The massive encroachment of metastasis upon his liver compounded the effects of his failing kidneys and left him agitated and confused. His progressive worsening clinical condition as a result of a chest infection, increasing episodes of abdominal pain from his liver metastasis and the pursuant encephalopathy from his hepatorenal syndrome resulted in the need for increasing doses of opioids and haloperidol.

The measured, proportional and closely monitored increases in his medications led to increasing levels of sedation that eventually left the patient comfortable but unconscious for the final 48 h of his life. The proportional use of opioids and antipsychotics in this case may be likened to what Quill24 has termed proportional palliative sedation (PPS). Quill describes the administration of PPS as being ‘intended to relieve refractory physical symptoms at the very end of life by using the minimum amount of sedation necessary to achieve that end. To relieve suffering may require progressive increases in sedation, sometimes to the point of unconsciousness, but conscious awareness is maintained as much as possible’.24

The patient's family members were aware that titrations of sedatives and opioids to ameliorate his worsening agitation and pain could potentially sedate the patient. The family consented to the proportionate application of opioids and haloperidol when the patient himself was no longer competent. There was clear and consistent documentation of the patient's wish for comfort measures only when he was in the final phase of life.

As a result of the application of haloperidol, the patient was deeply sedated for the final 48 h of his life and in a state that would meet LiPuma's9 conception of CSD. As with CSD, hydration was not started in the patient's case though in truth this was as the patient was already oedematous, hypoalbuminaemic and exhibiting early signs of respiratory tract secretions.9 The cessation of hydration and the employment of deep and continuous sedation till the patient's demise suggests commensurability with CSD application.

Discussion

Review of the patient's case involved analysis of the family members’ reactions to his condition as well as discussions with various family members.

The patient had a number of close family members and friends who visited him regularly and cared for him after he was diagnosed with a progression of his disease. Among this close circle of friends and family was his care-provider who had been employed by his family to help with his physical care soon after his initial diagnosis of bladder cancer. The care-giver and his close friends were regarded by the patient as ‘family’ and were frequently consulted about care determinations. They along with a few close relatives formed his ‘inner circle’.

Following his admission to hospital 5 days before his demise, the members of the patient's ‘inner circle’ were frequently at the patient's bedside either reading to him, praying for him or talking to him. Much of this was curtailed once his symptoms began to mount. This was particularly evident once his symptoms did not respond to standard treatment measures and the patient remained agitated. Some of the members of the patient's ‘inner circle’ withdrew from his side as a result of their own distress and helplessness at witnessing his suffering. Others continued to sit by him but chose to focus upon meeting his physical needs rather than engaging in conversation or even hold his hand given that it made him agitated at times. Most sat by him praying and reciting verses from their respective religious texts or remained quiet, hardly speaking to each other or to him. The patient's colleagues and friends stopped visiting.

Notably once the patient's symptoms were controlled, members of his ‘inner circle’ and even his other family members who had withdrawn from his side returned, calmer, relieved and eager to revive their active roles in his care. Interactions with the patient normalised and chatter, prayer and even laughter filled the room once more as many family members and friends reminisced about their shared encounters or news that they felt the patient would find interesting. ‘It's like a Chinese New Year's family gathering’, one relative commented.

The starting of sedation was a multidisciplinary team decision made following a holistic review of the patient's situation and motivated by the primary goal of relieving his suffering. While family distress was considered, the decision to apply sedation did not pivot upon it. PPS-like treatments are only applied as a treatment of last resort under the strict oversight of a holistically appraised concept of the patient's best interests and prevailing clinical guidelines. The application of this intervention is not taken lightly be either the palliative care team or the family.

For all parties, the implications were clear. Irrespective of his condition and level of consciousness, the patient's family maintained that he remained a member of their family. Many family members regarded the patient as being unchanged from his ‘premorbid’ self albeit that he was now ‘asleep.’ As with most local families of patients who are sedated, unconscious or non-communicative, the patient's family members regarded him as still invested with the familial and social roles that he had occupied prior to his deterioration. Furthermore, the family was clear that even while unconscious the patient was still deserving of the same level of consideration and respect that he had always enjoyed.

The family also stated that they were aware that there were ‘obligations’ to be carried out and social ‘standards’ to be met that were policed by the ‘wider’ family and community that the patient belonged to. Meeting these standards and obligations were a significant consideration for some members of the ‘inner circle’ especially his wife and influenced the action of the ‘inner circle’. I will discuss the implications of familial obligations and ‘face’ a little later.

Through a number of discussions with the patient's family and analysis of observation made of their practices it is evident that the attitudes and beliefs of the patient's ‘inner circle’ are consistent with those of other local families. This allows for analysis of the patient's case to highlight the realities of local attitudes towards personhood at the end of life and form the basis of a locally conceived concept of personhood called the Ring Theory of Personhood (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Ring Theory of Personhood.

Ring Theory of Personhood

Ring Theory of Personhood (‘Ring Theory’) consists of four domains that have, through the analysis of the patient's case, been shown to be key elements to local conceptions of personhood. These domains are depicted as rings. The manner that these rings interact with each another forms the basis for their positions within the Ring Theory.

Innate Personhood

Housing these beliefs in Innate Personhood is the innermost ring of the Ring Theory of Personhood (‘Innate Ring’). The Innate Ring is founded on the notion that all persons are imbued with human dignity and rights, irrespective of their stage of development or deterioration as a result of their connection with the Divine and or simply as a result of being alive and having human physical characteristics.20 25–28 The Innate Ring begins at conception and ends only with death.

There was variance in religious beliefs and cultural backgrounds within the members of the patient's ‘inner circle’; however the various members of the patient's ‘inner circle’ maintained a common notion of personhood, which was that all living persons deserved personhood. There was some disagreement as to when this innate form of personhood began but all agreed that personhood was present from birth and ended only when the person was biologically dead. This issue of determining the precise moment when personhood ended was important to the family given that the patient was deeply sedated for the last 48 h of his life.

Despite the array of religiosity and spiritual beliefs present among the ‘inner circle’ there was a secular notion that acknowledged that being alive and being human were pivotal to the endowment of personhood. Being human and being alive and potentially one's links with the Divine are seen as the Core Element of Innate Personhood (henceforth Core) owing to their unchanging features.

Discussions with the ‘inner circle’ also raise a second element to the Innate Ring, which is called the Secondary Ring. The Secondary Ring contains the secondary elements of Innate Personhood and encapsulates the Core (figure 1). The Secondary Ring contains changeable features that include the culture, religion and social roles that a person is born into. These facets may evolve with the taking of a new name, adoption of a new culture and or the embracing of a new religion. This notion was evident among a few of the patient's ‘inner circle’ that chose to renounce the faiths that they were born into in favour of a new spiritual structure. While some classified themselves as free thinkers, a number embraced Islam and as a result renounced their given names and cultures for a Muslim way of life. These changes they felt needed to be acknowledged in the Innate Ring given that it influenced the manner that one then conceives their personhood.

Discussions with the ‘inner circle’, particularly with respect to the Secondary Ring, highlight another feature about the Ring Theory. Personhood is held to be maintained by the person themselves as long as they are competent and are able to maintain their Individual Personhood. When Individual Personhood is compromised then personhood is endowed by others. Much therefore is dependent upon Individual Personhood.

Individual personhood

The second element of personhood, Individual Personhood, is depicted by the Individual Ring and is built upon the Innate Ring. It revolves around the higher functions of consciousness that includes features such as self-awareness, self-control, rationality and a sense of time, past and futurity as well as importantly a continuity of this identity over time.3–8 This ring relates to a person's ability to maintain his or her own personhood.

The Individual Ring highlights two key features of the Ring Theory of Personhood. The first is that it is the Individual Ring that allows a person to maintain his or her own personhood. However rather than being lost when Individual Personhood is lost or compromised, as is the case when CSD is applied and consciousness is suppressed, the Ring Theory holds that personhood persists as a result of the other rings. This flexibility in the manner that personhood is conceived reveals the second feature of the ring theory which will be addressed a little later.

On the issue of how personhood is conceived, those who were in the patient's ‘inner circle’ were clear on their belief that the patient maintained his own personhood for as long as he was conscious and competent. They added that when he was no longer able to fulfil this role it was they who knew him best should endow him with personhood in a manner that was consistent with his beliefs, values and goals.

The patient's ‘inner circle’ maintained that even though consciousness may have been lost the character, personality and indeed narratives of the patient were still retained within the other elements of personhood and particularly within the Relational Ring aided by the ‘scaffolding’ set out by the familial, societal and religious roles that the patient was born into and filled. These roles are seen to be specific to the patient and maintained by the family and society, which are then imbued with the particular characteristics and personality of the individual. Reliance upon social and familial roles and obligations highlights the acceptance of a further element of the Ring Theory, the relational aspect contained in both the Relational Ring and the Societal Rings that follow.

Relational Personhood

Relational Personhood is the third element of personhood and is contained within the Relational Ring. The Relational Ring contains those personal relationships that the patient considers important. In the patient's case, it is made up of the relationships he shares with those within his ‘inner circle’. The close personal ties the patient shares with his inner circle and thus the basis of his Relational Ring is built upon the individual characteristics and personality traits contained within the Individual Ring.

Membership to the ‘inner circle’ and to the Relational Ring is not limited to family members as the patient's case clearly illustrates. The Relational Ring may include friends and even paid carers. Membership of the Relational Ring is also not fixed and can alter. In the patient's case, his relationship with his uncle with whom he had once enjoyed a close relationship was fractured not long after his recurrence was diagnosed. This meant that the patient chose not to involve his uncle in his life plans and care decisions. Removal from his ‘inner circle’ meant that his uncle was not seen as part of the patient’s Relational Ring.

Maintaining a control of membership to the Relational Ring is deemed important to patients given that it is to these individual that patients turn to protect their interests and ensure that they are cared for in a manner that is consistent with their wishes, values and goals.

The Relational Ring is the means to protect and preserve the individual characteristics and interests contained within the Individual Ring highlighting the interdependence of the various rings within the Ring Theory. The Relational Ring is built upon the Individual Ring yet it is the Relational Ring that preserves the distinctive characteristics of the person as well as their interests once they are no longer able to maintain their own personhood. The Relational Ring also ensures that care of the patient moves beyond simple reliance upon the familial, religious and cultural backgrounds of the patient that are contained within the Societal Ring.

Societal Ring

Societal Ring, which contains Societal Personhood, contains two important elements. The first is that it contains the social, professional and familial ties that are not felt to warrant a place in the Relational Ring by the patient. As a result of their fractured relationship, the patient's uncle now belonged in the Societal Ring. These relationships shared with the patient were not felt to be sufficiently strong or personal enough by the patient to act to protect their interests.

The second element of this ring is that it contains the societal, professional and familial expectations and standards that the patient and those within their various rings are subject to. These expectations and standards are seen to police the actions of those that care for the patient.

Within the local setting this would also include the manner that familial obligations are met. Here all family members have obligations to other family members to care for them to a minimum standard that is set out by societal, familial and cultural standards. These minimum standards of care are also subject to oversight of legal and professional standards. Failure to meet these standards in the eyes of the Societal Ring will result in a ‘loss of face’. Ho et al20 defines the concept of ‘face’ within the local setting as “one's personal honour and dignity judged by his or her community. At the end of life, when the presence of filial piety is considered to be paramount, not performing one's duties properly would cause one to ‘lose face.’ This humiliation, in a society where relationships are treasured, is fearfully avoided”.

The Societal Ring also ensures that for patients who have no Relational Rings or even Individual Rings are provided with a minimum standard of care and a basic personhood that is in keeping with local cultural, societal and professional standards.

Flexibility of Ring Theory of Personhood: personhood in Singapore

Clinical experience and observations of local palliative care patients and their families suggests that patients see preservation of their personhood, particularly when they themselves cannot maintain this faculty, as key.

Thus the manner that personhood is preserved must be flexible and allow for personhood to be endowed when the patients are no longer able to maintain their own personhood. Personhood within the conception of the Ring Theory is not solely dependent upon any ring as long as the patient is alive. Personhood can be maintained by only the Innate Ring.

Flexibility in the Ring Theory is not limited to how personhood is preserved but also in the manner that the personhood as a whole is conceived. The Ring Theory embraces a holistic view of personhood that engenders conceiving personhood as broadly as possible. Considering the effects of CSD upon the patient's personhood highlights that his Relational and Societal Rings both see still envisage him as a person while his Innate Ring ensures that personhood is maintained till his demise.

Conclusion

LiPuma9 suggests that the induction of deep continuous sedation ostensibly till death with little ‘potential for future conscious states’ negates personhood and renders a patient ‘dead’.

A more realistic view of personhood is that contained within The Ring Theory. First, The Ring Theory highlights the fact that local conceptions of personhood are complex and require good understanding of social, relational and societal factors.

Second, under The Ring Theory personhood is not conceived to pivot solely upon consciousness and as a result is not lost with the induction of treatments such as CSD. The Ring Theory distances this treatment of last resort for the amelioration of intractable suffering at the end of life from any comparisons with the practice of euthanasia.

Finally The Ring Theory serves to better inform healthcare professionals of the multidimensional nature of personhood and aid in formulating a clinically relevant means of understanding this concept which in turn will improve the provision of patient-centred care to all palliative care patients.

This framework can be adapted to other settings and even to other communities making the Ring Theory a credible means of conceiving should personhood within the end of life context.

Learning points.

Personhood is not defined solely by the presence of consciousness or the various elements contained within the Individual Ring such as self-awareness and self-determination. Personhood is in fact dependent upon the various elements contained within the Ring Theory of Personhood.

Conceptions of personhood are flexible and depend upon a holistic view of the patient, their psychosocial situation and those of their family and carers.

Personhood is not lost as a result of applications of continuous deep sedation at the end of life.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Nelson G. Maintaining the integrity of personhood in palliative care. Scott J Health Care Chaplain 2000;2013:34–9 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Materstvdt JL, Bosshard G. Deep and continuous palliative sedation (terminal sedation): clinical-ethical and philosophical aspects. Lancet Oncol 2009;2013:622–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Materstvdt JL. Intention, procedure, outcome, and personhood in palliative sedation and euthanasia. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2012;2013:9–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rich BA. Postmodern personhood: a matter of consciousness. Bioethics 1997;2013:206–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fins JJ, Illes J, Bernat JL, et al. Consciousness, imaging, ethics, and the injured brain. AJOB-Neurosci 2008;2013:3–12 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkinson D, Kahane G, Savulescu J. “Neglected Personhood” and neglected questions: remarks on the moral significance of consciousness. Am J Bioethics 2008;2013:31–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farah MJ, Heberlein AS. Personhood and neuroscience: naturalizing or nihilating? AJOB Neurosci 2007;2013:37–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farah MJ, Heberlein AS. Response to open peer commentaries on ‘Personhood and neuroscience: naturalizing or nihilating?’ Getting personal. AJOB Neurosci 2007;2013:W1–4 [Google Scholar]

- 9.LiPuma SH. Continuous sedation until death as physician-assisted suicide/euthanasia: a conceptual analysis. J Med Philos 2013. Advanced access (online) 28 Feb, 2013. http://jmp.oxfordjournals.org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/content/early/2013/02/27/jmp.jht005.full.pdf (accessed 2 Mar 2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devine PE. The species principle and the potential principle. In: Brody BA, Englehardt HT, eds. Bioethics: reading and cases. EnglewoodCliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1987:136–41 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chorchinov HM. Dignity conserving care—a new model for palliative care. JAMA 2002;2013:2253–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Twycross R. Quality of life in general topics. Introducing palliative care. 4th edn Oxon: Radcliffe Medical Press Ltd, 2003:5 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huijer M, Van Leeuwen E. Personal values and cancer treatment refusal. J Med Ethics 2000;2013:358–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saunders C. The philosophy of terminal care. In: Saunders C, ed. The management of terminal malignant disease. Baltimore, MD: Arnold, 1984:232–42 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis-Hill C. Identity and sense of self: the significance of personhood in rehabilitation. JARNA 2011;2013:6–12 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz KD, Lutfiyya ZM. “In pain waiting to die”: everyday understandings of suffering. Palliat Suppor Care 2012;2013:27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chorchinov HM, Haasard T, McClement S, et al. The patient dignity inventory: a novel way of measuring dignity-related distress in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;2013:559–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitwood T. Dementia reconsidered: the person comes first. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buron B. Levels of personhood: a model for dementia care. Geriatr Nurs 2008;2013:324–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho MZJ, Krishna L, Yee ACP. Chinese familial tradition and western influences: a case study in Singapore on decision making at the end of life. JPSM 2010;2013:932–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janssens L. Personalism in moral theology. In: Curran CE, ed. Moral theology: challenges for the future. New York: Paulist, 1990;2013:94 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schotmans P. Personalism in medical ethics. Ethical Perspect 1999;2013:10–20 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jans J. Personalism: the foundations of an ethics of responsibility. Ethical Perspect 1996;2013:148–56 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quill TE, Lo B, Brock DW, et al. Last-resort options for palliative sedation. Ann Intern Med 2009;2013:421–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishna L. Decision making at the end of life: a Singaporean perspective. Asian Bioethics Review 2011;2013:118–26 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krishna L. The position of the family of palliative care patients within the decision making process at the end of life in Singapore. Ethics Med 2011;2013:183–90 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goh CR. Challenges of cultural diversity. In: Beattie J, Goodlin S, eds. Supportive care in heart failure. Oxford,New York: Oxford University Press, 2008:451–61 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goh CR. Culture, ethnicity and illness. In: Walsh TD, Caraceni AT, Fainsinger R, Foley KM, Glare P, Goh C, Lloyd-Williams M, Olarte JN, Radbruch L, eds. Palliative medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier, 2007:51–4 [Google Scholar]