Abstract

Eagle syndrome (symptoms associated with an elongated styloid process (SP)) is commonly divided into two presentations. First, the so-called classic Eagle syndrome where patients can present with unilateral sore throat, dysphagia, tinnitus, unilateral facial and neck pain and otalgia. Second, there is the vascular or stylocarotid form of Eagle syndrome in which the elongated SP is in contact with the extracranial internal carotid artery. We describe two cases of internal carotid artery dissection associated with an elongated SP. One is a patient with ischaemic stroke and another with transient ischaemic attacks caused by an elongated SP. A surgical resection of the SP was performed on the former patient. Both patients were treated with anticoagulation and recovered well. A literature search only revealed two prior descriptions of carotid dissection in the context of an elongated SP.

Background

Highlight the possible association of an elongated styloid process (SP) (Eagle syndrome) and carotid dissection.

CT scanning, in particular with three-dimensional (3D)-reformations, is an extremely valuable imaging tool in diagnosing Eagle syndrome and evaluating the SP in relationship with other head and neck structures.

Case presentation

Introduction

In 1937 the otolaryngologist Watt W Eagle described the first cases with a constellation of symptoms associated with an elongated SP. This syndrome was then to bear his name. Eagle syndrome is commonly divided into two classic presentations. First, the so-called classic Eagle Syndrome where patients can present with unilateral sore throat, dysphagia, tinnitus, unilateral facial and neck pain and otalgia. The pain is usually referred to the ear, especially on swallowing. There can also be a foreign body sensation in the pharynx with a persistent dull aching sore throat. Second, there is the vascular or stylocarotid form of Eagle syndrome in which the elongated SP is in contact with the extracranial internal carotid artery. This can cause a compression or a dissection of the carotid artery causing a transient ischaemic event or a stroke. Compression of the perivascular sympathetic fibres can cause pain, which is provoked and exacerbated by rotation and compression of the neck. The pain is often referred to the periorbital region. Of these two presentations the classic presentation is much more common. Here we describe two cases of vascular Eagles syndrome involving dissection.

Case 1

A previously healthy 38-year-old man suffered from a sudden right-sided hemiparesis, dysarthria and bifrontal headache, assessed as a score of 12 on the NIH stroke scale (NIHSS). Acute CT brain showed no haemorrhage or infarction, but indicated a left-sided dense middle cerebral artery (MCA) sign. CT angiography confirmed a left M1 thrombus and a left-sided internal carotid artery dissection. Intravenous thrombolysis was given, but due to clinical worsening, neurointervention was performed with a successful thrombectomy of the left M1 thrombus and stenting of the left internal carotid artery. Secondary prophylaxis with aspirin and clopidogrel was initiated. Follow-up CT showed a small infarction in the left putamen. Subsequent CT angiography showed an elongated and calcified stylohyoid ligament on the left side (figure 1). The carotid artery was located in close contact with the stylohyoid process and was suggested to be the cause of the carotid dissection. The symptoms completely regressed. An otorhinology specialist was consulted and radiological follow-up was planned. A few days prior to the 3-month follow-up the patient, while driving a scooter, had an attack of right-sided paresis and aphasia lasting for 45 min. A brain CT and angiography at a local community hospital were considered normal. The dual-antiplatelet therapy was not altered. One week later, the patient had again symptoms of aphasia and right-sided arm paresis, lasting 10 min. MRI of the brain indicated a 3–4 mm insula infarction on the left side and MR-angiography showed a distal M1 stenosis and a short occlusion of the M2 segment. The left carotid stent showed irregularities possibly indicating a small intrastent thrombosis. The treatment regimen was subsequently changed to a heparin-infusion for 5 days. The patient was discharged without symptoms on low-molecular heparin injections twice daily. The following morning, the patient suffered again from right-sided hemiparesis, right-sided sensory affection and aphasia. CT scan indicated a low-attenuated left frontal infarction. CT angiography showed thromboemboli in the distal part of left M1 and new emboli in the left A2-segment. MRI the same day showed a perfusion–diffusion mismatch in the left hemisphere and new focal frontal infarctions, which led to a conventional angiography with additional stenting of the left internal carotid artery (ICA) and a thrombectomy of the left M1 thrombus. A stent was also introduced in the left pericallosal artery but without successful recanalisation. Secondary prophylaxis was altered again to clopidogrel and aspirin. A control-CT showed increased frontal infarction and there was a slight worsening on the NIHSS scale from 2 to 4 points. A new MRI showed cortical infarcts in the anterior parts of the MCA and anterior cerebral arteries territories, as well as in the genu and trunc of the corpus callosum and a multitude of small embolic infarcts on the left side. An otorhinologist was consulted. A surgical resection of the SP with an external approach was performed without complications. A postoperative CT angiography indicated that the remaining part of the stylohyoid ligament was still in close contact with the internal carotid artery (figure 2), but it was suggested that further extraction would entail a too high risk and could cause a rupture of the carotid artery or damage to the facial nerve. Postoperatively there was a slight worsening in dysphagia which was resolved. A rehabilitation period followed. At 6 month follow-up the patient was clinically intact with a NIHSS of 0 points and mRS of 1. Control CT-angiography at 6 months showed good flow in the stent in the internal carotid artery. Secondary prophylaxis was now altered to clopidogrel only.

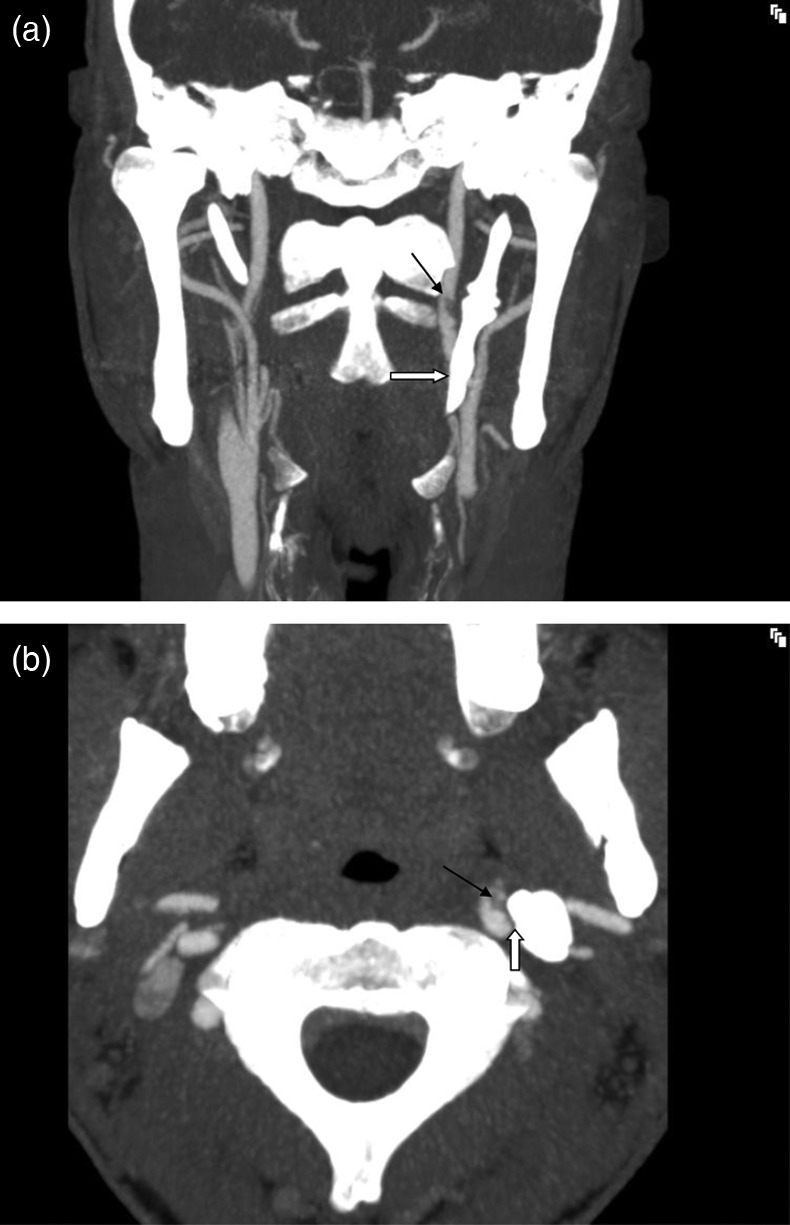

Figure 1.

A CT-angiography with coronal view of the neck shows an elongated styloid process (SP) (white arrow) in close proximity to the internal carotid artery (ICA) on the left side. Note the filling defect from the clot in the vessel (black arrow). (B) CT-angiography with axial view of the neck shows the close contact between the SP and the ICA on the left side (white arrow). There is a clot in the vessel due to dissection (black arrow).

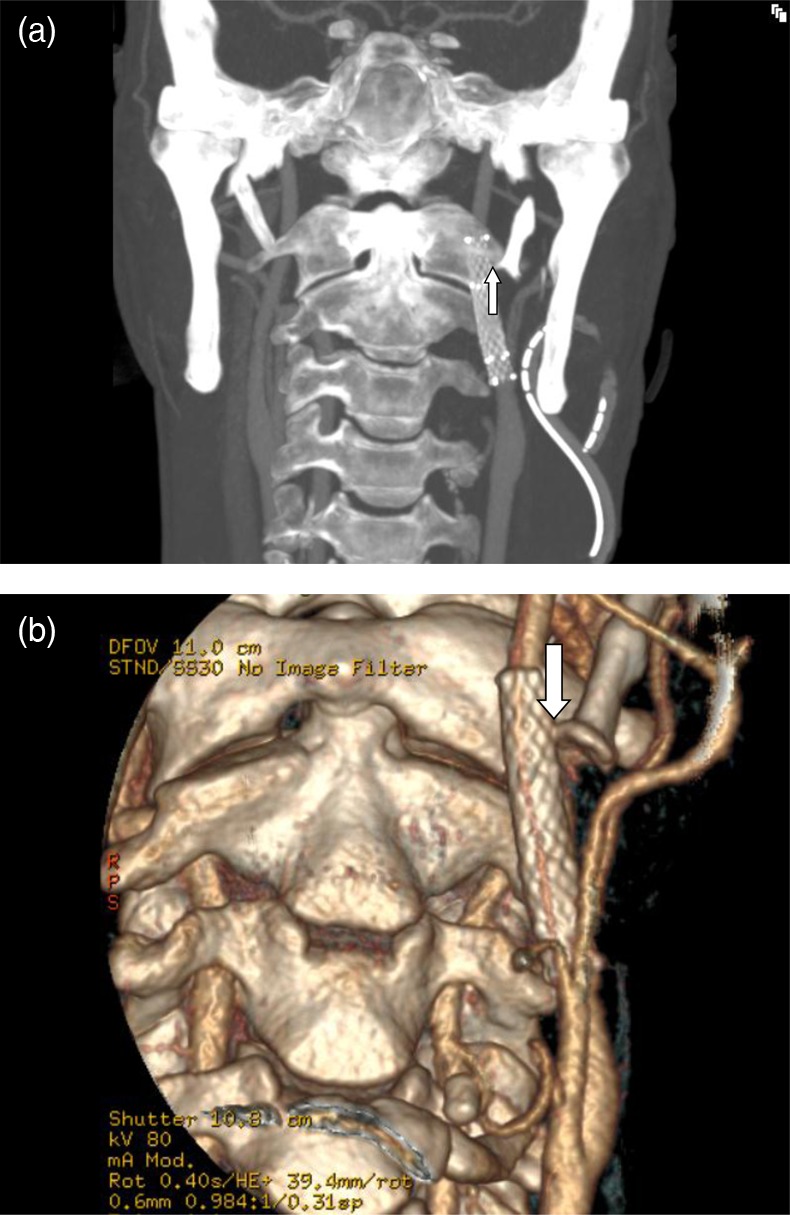

Figure 2.

A Coronal view of CT-angiography of the neck after partial resection of the styloid process (SP) on the left side. Note the close relation of the remaining process with the internal carotid artery (ICA) stent (arrow). (B) A three-dimensional image of the neck after partial resection of the SP on the left side, still in close proximity with the ICA stent (arrow).

Case 2

A 41-year-old healthy woman, without any riskfactors for cardiovascular disease, suffered from a sudden severe headache in the right temple after intensive physical exercise at a gym (boxing) and sought the emergency department. There a CT angiogram showed a dissection of the right internal carotid artery with a small pseudoaneurysm. The angiogram also showed an elongated SP with calcified stylohyoid ligament which had close relation with the dissected artery, with the vessel wall lying immediately adjacent to the process (figure 3). She was treated with a continuous intravenous infusion with unfractionated heparin. Her clinical condition improved besides a few short-lived intensive headaches in the next days and two short episodes of numbness in the left arm. Neurological examination was normal. There were no signs of Horner’s syndrome. MRI of the brain was normal. Four days after admission warfarin treatment was started. The patient was treated with warfarin for 3 months. A follow-up CT-angiography showed almost complete resolution of the dissection with healing of the pseudoaneurysm (figure 4). After a consultation with an otorhinology specialist it was decided not to operate the elongated SP unless she would have new symptoms. Warfarin treatment was changed to aspirin. A follow-up CT-angiography 6 months later showed complete normalisation of the artery. Aspirin treatment was discontinued. The patient has not had any new events but avoids intensive physical training, especially boxing.

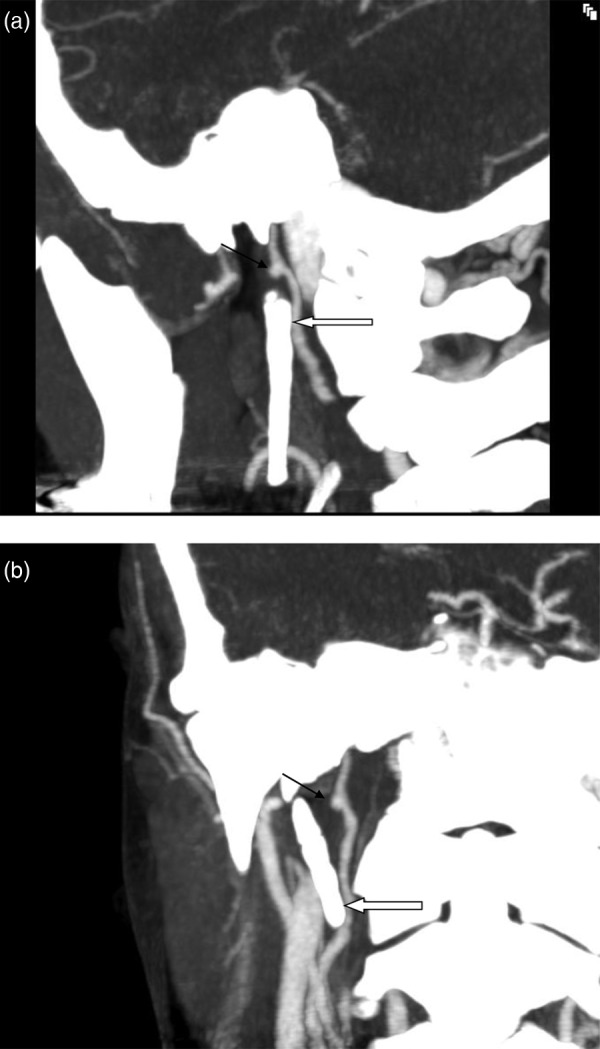

Figure 3.

A. CT-angiography, lateral view, with the elongated styloid process (SP) in close contact with internal carotid artery (ICA) (white arrow) which is narrow and irregular due to dissection with a small pseudoaneurysm (black arrow). (B) CT-angiography, frontal view, with an elongated SP in close contact with the ICA (white arrow) which is narrow and irregular due to dissection with a small pseudoaneurysm (black arrow).

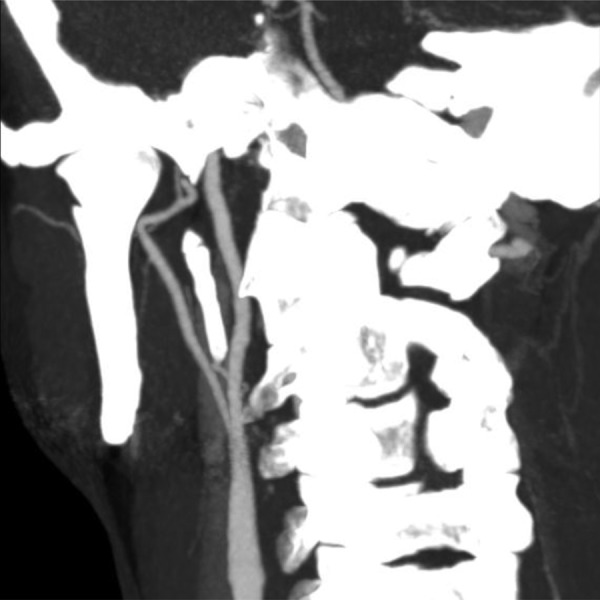

Figure 4.

CT-angiography of the neck 2 months after admission with almost complete resolution of the right internal carotid artery dissection.

Discussion

Here we describe two cases of internal carotid artery dissection associated with an elongated SP. Literature search only revealed two prior descriptions of carotid dissection in the context of an elongated SP.1 2 These two cases were similar to our second case. Both cases had transient ischaemic attack attacks (aphasia and aumaurosis fugax) and were treated with anticoagulation for 3 and 6 months, respectively. For obvious reasons there are no treatment guidelines for Eagle syndrome and carotid dissection, but our first case was operated because he had severe recurrent symptom that were thought to stem from the elongated SP.

Eagle originally proposed that the normal upper length of the process should be 2.5 cm.3 Subsequent studies have observed lengths from 1.52 to 5.0 cm.4–6 Most authors agree with Eagle that SPs greater than 2.5 cm in length should be considered abnormal. The aetiology of an elongated SP has yet to be elucidated and the topic is still being debated. Eagle considered that surgical trauma (tonsillectomy) or local chronic irritation could cause osteitis, periosteitis or tendonitis of the stylohyoid complex with consequent reactive, ossifying hyperplasia being the cause.7 The reader is referred to Mortellaro for a good review of current theories.8

The typical patient with an elongated SP is a female between the ages of 30 and 50 years, but the syndrome has been found in teenagers and in patients over 75-years-old. There is a 3 : 1 female predominance.9 Eagle originally put forward a 4% prevalence estimate of elongated SPs in the general population. However, according to him only 4% of patients with elongated processes will be symptomatic, estimating the lifetime incidence of symptomatic SP being around 0.16%.10

CT scanning, and in particular with 3D-reformations, is an extremely valuable imaging tool in patients with Eagle syndrome. It offers an accurate evaluation of the SP in relationship to other head and neck structures, which is imperative in regard to surgical planning.

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, treatment is often surgical. Two approaches have been described for the removal of a SP: internal and external.11 Eagle introduced the internal approach but today the external approach is most often used. The most significant advantage of an external approach is enhanced exposure of the SP and the adjacent structures. In a large case series of 61 patients with elongated styloid, the external approach was always used without any serious complications.12

Learning points.

In patients presenting with a carotid dissection it is important to think of an elongated styloid process (SP) as a possible cause.

CT scanning, in particular with three-dimensional reformations, is an extremely valuable imaging tool in diagnosing Eagle syndrome and evaluating the SP in relationship to other head and neck structures, which is imperative in regard to surgical planning.

There are no treatment guidelines for Eagle syndrome and carotid dissection.

Antithrombotic treatment is recommended for the dissection.

Operation for the elongated SP should be decided on an individual basis.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in diagnosing and treating the patients. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Zuber M, Meder JF, Mas JL. Carotid artery dissection due to elongated styloid process. Neurology 1999;2013:1886–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cano LM, Cardona P, Rubio F. Eagle syndrome and carotid dissection. Neurología 2010;2013:266–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eagle WW. Elongated styloid process; symptoms and treatment. AMA Arch Otolaryngol 1958;2013:172–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moffat DA, Ramsden RT, Shaw HJ. The styloid process syndrome: aetiological factors and surgical management. J Laryngol Otol 1977;2013:279–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman SM, Elzay RP, Irish EF. Styloid process variation. Radiologic and clinical study. Arch Otolaryngol 1970;2013:460–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung T, Tschernitschek H, Hippen H, et al. Elongated styloid process: when is it really elongated?. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2004;2013:119–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eagle WW. Elongated styloid process: further observation and a new syndrome. Arch Otolaryngol 1948;2013:630–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortellaro C, Biancucci P, Picciolo G, et al. Eagle's syndrome: importance of a corrected diagnosis and adequate surgical treatment. J Craniofac Surg 2002;2013:755–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ilguy M, Ilguy D, Guler N, et al. Incidence of the type and calcification patterns in patients with elongated styloid process. J Int Med Res 2005;2013:96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eagle WW. The symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of the elongated styloid process. Am Surg 1962;2013:1–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss M, Zohar Y, Laurian N. Elongated styloid process syndrome: intraoral versus external approach for styloid surgery. Laryngoscope 1985;2013:976–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ceylan A, Koybasioglu A, Celenk F, et al. Surgical treatment of elongated styloid process: experience of 61 cases. Skull Base 2008;2013:289–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]