Abstract

Background:

Life-threatening and stressful events, such as myocardial infarction (MI) can lead to an actual crisis, which affects the patients spiritually as well as physically, psychologically, and socially. However, the focus of health care providers is on physical needs. Furthermore, the spirituality of the patients experiencing heart attack in the light of our cultural context is not well addressed in the literature. This study is aimed at exploring the spiritual experiences of the survivors of the MI.

Materials and Methods:

In this qualitative research a grounded theory approach was used. Key informants were 9 MI patients hospitalized in the coronary care units of 3 hospitals in Shiraz. In addition, 7 nurses participated in the study. In-depth interviews and a focus group were used to generate data. Data analysis was done based on Strauss and Corbin method. Constant comparison analysis was performed until data saturation.

Results:

Five main categories emerged from the data, including perceived threat, seeking spiritual support, referring to religious values, increasing faith, and realization. The latter with its 3 subcategories was recognized as core category and represents a deep understanding beyond knowing. At the time of encountering MI, spirituality provided hope, strength, and peace for the participants.

Conclusion:

Based on the results we can conclude that connecting to God, religious values, and interconnectedness to others are the essential components of the participants’ spiritual experience during the occurrence of MI. Spirituality helps patients to overcome this stressful life-threatening situation.

Keywords: Grounded theory, heart attack, myocardial infarction, qualitative research, religion, spirituality

INTRODUCTION

Myocardial infarction (MI) is an acute, stressful, and life-threatening event,[1] which causes a change from a wellbeing status to a serious illness that threatens the patient’s life.[2] This condition could be a real crisis and a unique experience, leading to psychological, social, and specially spiritual as well as physical outcomes.[3] Due to high prevalence, long-term and expensive treatment, and high mortality and morbidity of MI,[4–11] a great deal of research has been conducted in this realm. Nevertheless, these studies have generally focused on biological and physiological aspects of disease, neglecting the patients’ experiences.[10] Furthermore, limited studies conducted on the patient’s experiences during the recovery of MI,[2,10,12–17] but none of them focused specifically on its critical initial phase.

Because of the life-threatening nature of heart attack, health care providers mainly focus on physical needs,[13] whereas the patients prefer to be seen as a whole person and not just at the disease and ignorance of any human aspects can interfere with healing.[18] Also it is highlighted that spirituality as a substantial quality in human beings and a natural process that occurs in all patients[19,20] has a positive correlation with satisfaction of nursing care.[19] Illness, suffering, and facing death are all spiritual experiences, and spirituality can play an important role in the recovery process.[15]

The findings of many quantitative studies conducted on spirituality in cardiac patients support the association between spirituality/religion and prevalence of heart attack risk factors, especially stress,[21–24] quality of life improvement, and self-efficacy after MI,[25] psychological health and coping,[23,25,26] and so on.

Subjective and abstract nature of spirituality, necessitate researchers to use qualitative approach so that enabling them to explore the patients’ spiritual experiences during the heart attack. It is believed that the individual’s perception of an experience is influenced by many factors, such as context and personal background. Thus, meaning of an experience cannot be the same for the researcher and participants.[27] Therefore, it is recommended that researchers who assess the spiritual concepts and their relationships to health and illness management should consider the participants’ subjective experiences according to their own definition of spirituality rather than those of the researchers’.[27,28] Moreover, spirituality is interwoven with culture,[29] and qualitative approach provides opportunities for researchers to understand how culture forms meaning.[30] There are a few studies about spiritual experiences of MI patients in the light of cultural context.[31] Regarding this gap, especially in the most critical phase of heart attack, this investigation was conducted to describe the spiritual experience of the survivors of MI from the onset of symptoms to elimination of the critical condition.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

In this study, a grounded theory design that is appropriate for guiding nursing practice was used. Grounded theory will result in the development of explanatory theories for human behaviors in social context and especially in the areas in which little is known.[30]

The key informants were 9 MI patients (4 female and 5 male) who were hospitalized in coronary care units (CCUs) of 3 hospitals in Shiraz in the southern Iran. All the participants were in a stable condition with an age range of 33-71 years. They were all married except for one who was a widow, and all of them were Muslims.

Seven nurses, from CCUs and emergency departments (EDs) were involved in the study to obtain a more comprehensive data. All of them were women, baccalaureate with a mean work experience of 6.7 years in CCU and ED (3-14 years). In this article, the word “participants” refers to the patients who were the survivors of the MI and were the key informants.

A multisource data-generation approach was applied in this study. Purposive sampling was used regarding the main question and objectives of the study and then theoretical sampling was done to develop the concepts and to emerge basic social processes in data. Iterative cycle of data generation was continued until data saturation. In-depth semi-structured interviews each lasting 20-60 min were conducted with patients. Nurses participated in a focus group, which lasted 95 min. Interviews and focus group were conducted by the first author. All the interviews were tape-recorded and then transcribed verbatim.

Data collection and analysis were performed simultaneously. At first, each transcript was read line by line and then coding was done in 3 stages as recommended by Strauss and Corbin.[32] After each interview and throughout the data analysis, the researcher wrote the theoretical memos, which were included in the coding process. The basic concepts were extracted in the open coding stage. Through constant comparison, similarities and differences were explored, data were clustered, and eventually the categories were emerged from the well-developed concepts. The further interviews helped to clarify the categories. Subcategories and their relationships were explored through axial coding, and in selective coding the relationships between categories and core variable were determined.

Lincoln and Guba’s criteria for qualitative research rigor, including credibility, transferability, confirmability, and dependability,[33] were considered in this study. Prolonged engagement, close interaction with the participants, member and expert checking, reflexivity, immersion in data, and recording all activities support the trustworthiness of this study.

Ethics committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences approved this study. An informed consent was obtained from all the participants after they were provided with verbal and written explanation about the research and assurance of confidentiality and anonymity.

Findings

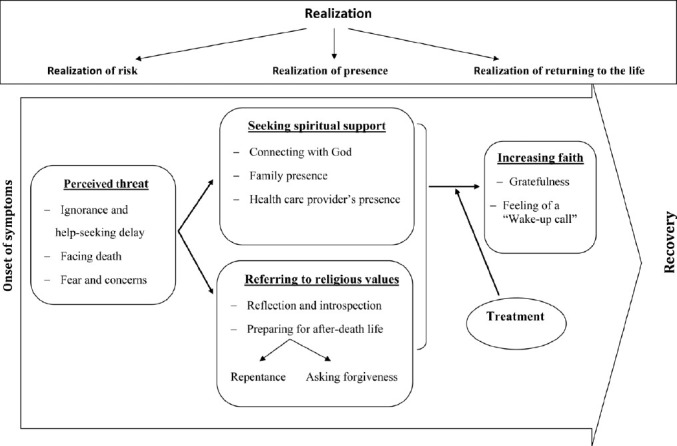

The patients’ spiritual experience during the MI from the onset of symptoms until elimination of the critical condition could be categorized into 5 main categories and 13 subcategories. These categories included perceived threat, seeking spiritual support, referring to religious values, increasing faith, and realization [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Spiritual experience of the survivors of the myocardial infarction

Perceived threat

On the onset of symptoms, the participants ignored or tried to manage them. As the symptoms were intensified and impending death was felt, they perceived that their life, health, independence, and roles were threatened. This category is constructed by following 3 subcategories:

Ignorance and help-seeking delay

A delay of more than 2 h was reported from the onset of the symptoms till seeking help by all the participants except one who recently observed a case of MI in his relatives. During this phase, the patients struggled to tolerate the pain or ignore it. Influential factors of such delay could be categorized as cognitive factors (knowledge deficit and incorrect interpretation of symptoms), psychologic factors (unexpectedness of the heart attack and denial), and spiritual factors (unwillingness to disturb family, praying for symptoms to go away, and hoping for the effectiveness of home remedies).

The following phrases are samples of the patients’ statements, which express their reasons for delay in seeking help:

“I had pain. I came home from work to inform my family. Although I had severe pain, I tried to hide it so that they don’t panic” (42-year-old man).

“I felt there is something related to my stomach and I tried to control it by some herbs and home remedies” (44-year-old man).

What makes the individual postpone the treatment is lack of realization of risk. Provided that the patient realizes that his/her heart is at risk and it is quite serious, he/she would not hesitate to seek help and treatment. A male participant mentioned:

“At that time (onset of symptoms) I didn’t think that I had had heart disease. I thought it is something trivial. Nevertheless, I did not know that I was challenging the most important organ of my body, my heart. I absolutely had no idea it was from my heart. If I could guess, I would have definitely referred for a checkup in a clinic” (44-year-old man).

Facing death

Delay in help-seeking leads to intensification of the symptoms. Severe pain and shortness of breath results in bad physical status. All the participants experienced such a condition and they had seen their life ending.

“I was just thinking about death. I could not breathe. I felt I was choking. I didn’t feel I was alive anymore” (40-year-old woman).

Fear and concerns

Severe chest pain and other symptoms led to intense fear and panic. Fear of death, disability, pain, and dependency were reported by patients. For the elderly participants, disability was the most important concern. A 71-year-old woman said:

“I am not afraid of death at all. Death is a reality. I lived enough. I have everything. I have no worries. I am just afraid of disability and dependence on others.”

One of the important concerns of all the participants was their families. They were fearful and anxious toward the condition of their family members. This anxiety was about financial and familial integrity issues. A concern about the future of children, mainly younger ones, was experienced by all the participants and mostly by women. Some patients stated that more than being worried about themselves, they were worried about their children. Some patients’ statements are as follows:

“I would like to be with my wife and my children. If any family loses its caretaker, it would be like herd without the shepherd. But if I stay alive, I would guide them and solve their problems” (52-year-old man).

“I have asked God if my life is over; give me another chance to go back to my children. After they grow up I would surrender to whatever he wills” (33-year-old woman).

Seeking spiritual support

Following the perception of threat and when the participants realized that they were at risk, they got fearful and there was a need to seek help. This need had physical, psychological, and spiritual dimensions. They decided to refer to a medical center as soon as possible and asked God and others for help and support. The 3 subcategories of this concept are as follows:

Connecting with God

All the participants consider God as “The Almighty” and they believe that their life, death, sickness, health, and fate are in the hands of God.

“Life and death is in the hand of God. We are his servants. We are his crops; he reaps us whenever he wishes” (71-year-old woman).

They felt a connection with God since the onset of the heart attack symptoms and they asked him for help. With intensification of the symptoms and “realization of risk,” this connection strengthened and they felt that the only powerful support is God. He is powerful enough to help them and is the only reliable source of support. Therefore, they have trusted him. Believing in God as the mighty power and the one whose mercy is upon everyone, brought them hope and peace in that critical situation. Most of them considered the health care providers as a tool in the hands of God on whose will their success depended on. According to this, the participants talked to God and prayed for their survival and recovery. They believed that God has heard them and he would answer them. The results of praying were peace, comfort, and hope. Here are examples of what the patients and nurses mentioned:

“God can give life to a dead person. I told myself God knows I’m here. I was praying all the time. That is why my treatment was done successfully” (40-year-old woman).

“I was saying please help us God. What happens is what you will. What he wills is good. Nothing happens without his permission… God answers you when you call him” (47-year-old woman).

Family presence

Family presence and support, especially in this critical stage of MI, had a positive influence on the patient. Female participants, in particular, considered their spouses’ attendance as soothing. A woman said:

“I liked my husband to be next to me. With him, I was calm. I had more pain when I was alone” (33-year-old woman).

This was taken into account by nurses. One of them expressed:

“The presence of the patient’s companion is supportive since the patient has entered a new strange place” (A CCU head nurse).

All the participants were dependent on their families in this situation and were taken to the hospital by them. Because of their families, they had not thought about emergency services. If there is another attack, they tend to use the emergency services in case they are alone, as mentioned by some of them.

Health care providers’ presence

The participants considered health care providers’ presence in a critical situation, such as heart attack, as comforting and pacifying and they preferred that nurses stay with them. Some patients considered physicians and nurses as their rescuers, showed affection toward them, and described them as their close relatives.

“They (doctors and nurses) really took care of me. I owe them a lot. I felt great when they helped me, as if they were so close to me. They were really kind” (40-year-old woman)

The primary results of the treatment, such as pain reduction and improvement of physical condition along with the presence and spiritual support by the treatment team and the family, played a significant role in resolving the critical condition. At the time of MI, the patients realized that they were not alone and they deeply felt the presence of almighty God and other people who helped and supported them. This feeling provided hope and peace for the participants.

Referring to religious values

All the participants in this study were Muslims and religion was an integral part of their lives. They believed in life after death and being responsible for their behaviors. Reflection and introspection, and preparing for after-death life are 2 subcategories for this concept.

Reflection and introspection

Following encounter with death, the participants reflected on their behaviors and compared them with their religious beliefs and values. Different patients having varying degrees of religious beliefs expressed these thoughts.

“I told myself it may be the last moment of your life. You may not get to the hospital, have you got anything to take with you?” (44-year-old man)

Preparing for after-death life

Regarding their religious beliefs, the participants had a tendency to prepare for life after death. Through reflection, they considered themselves guilty and asked God for forgiveness by repentance.

“I asked God to forgive me if I have committed a sin” (40-year-old woman).

On the other hand, the participants asked their family and relatives for forgiveness.

“I said to my wife if I die, please forgive me” (58-year-old, man).

Increasing faith

Faith was an inseparable part of the participants’ lives. They mentioned that their life is based on their faith. While experiencing a heart attack, they gained a new insight that developed and strengthened their faith and gave them a new worldview in which faith is more highlighted. This category includes 2 subcategories.

Gratefulness

As physical condition improved, the fear and turmoil was declined and the participants could believe that their treatment was successful and they have overcome the danger. Therefore, they started to contemplate on their situation and think about possible events that could have occurred. They realized that it was just God who sent them back to life. As a result, they started to thank God. All of them considered their survival as mercy from God and they were grateful. The following are some of their statements:

“I thank God for helping me to get to the hospital and get cured. Many people didn’t and passed away” (44-year-old man).

They also thanked nurses and doctors who had tried to save them and the older participants prayed for the treatment team besides thanking them. One of the nurses mentioned:

“Some patients tell us that we have saved their lives, they thank us and pray for us, especially old patients” (Emergency nurse).

The participants appreciated the presence and support of their family members and relatives. This strengthened their feelings of being loved by others and gave them courage and hope.

“To know that one is important for others and they really love him makes him strong” (38-year-old man).

Feeling of a “wake-up call”

Some participants believed that MI was a sign or message which revealed the necessity of change in their lives physically and spiritually.

“Heart attack was an alarm which warned me that there is a problem in my heart and I have to change my life-style. This was a spiritual alarm too, which showed me death is close and we are nothing when compared to the almighty God’s power” (44-year-old man).

Realization

The core category in this study was “realization,” which was relevant to other categories and is the most effective element in emergence and improvement spirituality in the recovery process of the heart attack. “Realization” means that during the heart attack, by thinking about what has happened, the patients went beyond the borders of knowing and reached a deep understanding. As a result, their spiritual aspects are manifested and appeared in the form of spiritual thoughts and behaviors. Realization has 3 subcategories, including realization of risk, realization of presence, and realization of returning to life. These subcategories match with the main categories of the participants’ spiritual experience [Figure 1]. Realization of risk resulted in perception of threat and seeking help, realization of presence provided the feeling of spiritual support, hope, and peace, and realization of returning to life increased the participants’ faith.

DISCUSSION

In this research, the experience of the survivors of the MI represents the role of spirituality in undergoing such dangerous and stressful process. Some studies have shown that people who face a life-threatening situation focus more on their spiritual interests.[34] In other words, cardiovascular diseases make an individual’s spiritual aspect eminent.[35] It seems that even in secular societies spirituality is quite important for patients and quite effective in heart attack recovery.[31]

In spirituality investigations, the participants’ cultural context should be taken into account, because spirituality is embedded in culture.[29] Ninety-eight percent of Iranians are Muslims and mostly Shiite (90%).[36] All the participants were Muslims and their religious beliefs were reflected in their thoughts, behaviors, and even in their familial and social relations. Religion is interwoven with Muslim’s life, and culture and religious beliefs are important in their life particularly in critical situations.[36] Rasool (2000) believed that in Islamic contexts, spirituality does not exist without religious thoughts and practices and religion provides a spiritual path for life and salvation.[37] The result of this study verifies this viewpoint.

Spiritual experience of the participants who confronted a MI initiated with perception of a risk which threatened their life and health, and enhanced their spirituality. Camp (1996) mentioned that heart disease can bring one’s spiritual side in a greater focus.[34]

Despite the significance of time and its effect on patients’ mortality and morbidity[38,39] initially they ignored the symptoms. Other studies reported the hours and even days of delay for seeking help among these patients worldwide.[5,9,39–42] The main reason of this delay is the long process of decision making[40] which is influenced by some factors. In several studies, cognitive factors, such as misperception and misinterpretation of symptoms are the most important effective factors leading to patients’ ignorance of the symptoms until they are intensified.[11,38,40,41] In the present research, also, cognitive factors were mentioned as one of the major reasons for delay.

Denial of the heart attack as a defense mechanism had been used by a number of participants. Using this mechanism is also reported by other studies as well.[3,13,43] The significance of the heart as a vital organ of the body was a reason of this denial.

There were some spiritual reasons for help-seeking delay. Tolerating pain for preventing disturbance of the family, praying for symptoms to go away, and hoping for the effect of home remedies were spiritual behaviors that were reported. In other studies, these behaviors are mentioned as common reasons for delay in seeking help.[11,38–40,42,44]

After the initial struggle with the symptoms, and when they realized that the situation was critical and they were at a serious risk, the participants sought for help. Emotions and thoughts about the reality of death, which was found as motives for seeking help in this study have been manifested during a heart attack elsewhere.[3] The findings of other studies also support the occurrence of strong and lasting sense of coming face to face with one’s own mortality.[45,46]

Facing death and the belief that God is the super power and almighty made all the participants have a connection with God from the onset of the symptoms and even before they seek help from the family and treatment team. Connection with God and receiving his presence by patients who experienced a heart attack is also supported by other studies.[13,15] Trust in God, prayer, and seeking strength from him has been discussed as the most common coping mechanisms for facing stressful situations.[24] In fact, believing in a higher power positively affects coping with critical situations, such as emotional distress and death.[36] Since the initial period of MI, which is characterized by much anxiety and uncertainty, beliefs in God may give patients the inner strength, resulting in better physical and perceived recovery.[3] Praying is a channel through which we directly connect to God.[47,48] One who prays is faithful and hopes his/her voice would be heard by a higher power[49] and as a result his inner power strengthens and increases.

Following impending death and the consequent fear, the interviewees decided to get to a hospital by getting help from their families. The family members’ presence and support have been described as quite effective in this situation. The most important functions of a family during this crisis have been counseling, transferring the patient to a hospital, and providing emotional support. In this respect, Halligan (2006) mentioned while nurses consider the physical aspect of care, families play a leading role in approaching the patient’s emotional, social, and psychological needs.[50]

Since long ago, familial relationship had an influence on the whole life of an individual in Iran’s sociocultural context.[51] Even the concept of care from Iranian point of view is involved in familial relationship.[52] In Iran, which is a traditional or at least a transitional society, collectivistic culture is prominent. In this cultural context, people have an intimate relationship with each other and are absolutely affected by others’ thoughts and behaviors.[53] Deep relationship among family members, on the other hand, can lead to anxiety at the time of heart attack. All of the participants mentioned their families as one of their greatest concerns. Male participants were mainly concerned about financial issues, familial integrity, and children’s situation. However, female participants were mostly concerned about their children and their future. This concern was due to the responsibility that they had as a parent. Traditionally, Iranian women’s fundamental responsibility is to nurture the children in spite of their increasing presence in business and social activities, while men fulfill financial activities and play a basic role in preserving their family integrity.[54] In this respect, the participants’ concerns at the time of heart attack is based on this cultural background.

At the time of MI, the presence of the husband provided peace, support, and comfort for female participants. The influence of interpersonal relationships is also confirmed by biological studies. For instance, it was specified in an interventional study that anxiety was considerably decreased in women who had held their husband’s hands.[55] In a qualitative study, women hospitalized in CCU found themselves dependent on friends and relatives’ help and support. This support created hope and optimism toward their future.[14] Feminine gender role values which focus on close relationship, care, and emotional manifestations, encourage women to show their dependency, while masculine gender role values, which emphasize independence and emotional inexpressiveness prevent men from revealing their dependence.[56]

Caring presence, emotional support, and interventions provided by the treatment team are important in achieving peace, comfort, and hope. The reassuring effect of the nurses and doctors’ caring presence is also reported in other studies.[13,15] Most nurses intuitively feel that sometimes their physical presence can be the best medicine for the patients. They often provide the greatest amount of spiritual care by just being with the patients.[48] The essence of the presence is the healing relationship, which includes mutual interaction beyond technical care and has a positive effect on the recovery, healing, and reciprocal trust.[57]

Confronting death made the participants reflect about their performance in the light of religious values. Believing in life after death is one of the basic principles of Islam. Muslims believe that although God is very compassionate and merciful, life after death is founded by life in the present world.[58] Consequently, they have asked God for forgiveness. Repentance, along with the hope for God’s mercy calmed the participants.

Increasing faith was another main category in patients’ spiritual experience during heart attack. Initiation of the treatment led to relative elimination of fear. Regarding the prolonged nature of heart attack recovery, the participants’ fear is not completely gone away and their fear of another attack, disability, and death remains. By physical improvement, the “realization of returning to life” appeared and the participants made a new insight through reflection about the event resulted in raising their faith. Connecting with God and the effective presence of the personnel and family members has an outstanding influence on reaching peace and releasing stress. The participants have noticed such influence very well and thanked God, personnel, and their families. Spirituality and religious beliefs helped patients to experience hope, peace, and comfort during the recovery process of MI and to cope with this crisis. Other studies support this finding.[3,13,15]

Many authors believe that spirituality is experienced in relationship with God, self, others, and nature.[29,48,59] In this study, praying, reflection on previous performance, and interaction with others, including family members and personnel manifest such relationships. The participants did not talk about nature. It seems that in such a life-threatening experience, the participants were more concerned about their lives than the environment.

The limitation of this study was the impossibility of interviewing during heart attack because of the critical condition of the patients. Therefore, interviews were done in 3-5 days after the attack when the participants were stable physically and psychologically.

These findings are context based and as mentioned before they are related to Iranian religious and cultural texture. Therefore, this study provides a better understanding of spirituality and the importance of delivering spiritual support in getting through with the crisis of MI in the light of culture.

Future studies can be conducted to understand the importance of spirituality for individuals and families during the experience of the further stages of recovery from MI and to explore the role of spirituality in other acute life-threatening illnesses.

The results showed that the life-threatening and stressful nature of MI strengthens the participants’ spiritual aspect. Connecting to God, religious values, and interconnectedness to others are the essential components of the participants’ spiritual experience during the occurrence of MI. Spirituality helped the participants to undergo such critical condition and affected their recovery. In Iranian culture, in which religion is embedded, spirituality is crucial during illness and recovery. The relationship of heart attack survivors’ spirituality with their physical, psychological, and social aspects was clearly illustrated in this study. Therefore, health care providers are suggested to consider the patients’ spiritual needs and concerns as well as other aspects of care when MI occurs.

ACKNOWLEGMENT

The authors would like to thank the participants’ intimate cooperation. This manuscript is a part of the PhD dissertation of Marzieh Momennasab, which is financially supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, NO: 88-4882.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This article is a part of a larger study, which is financially supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.ginzburg K. Life events and adjustment following myocardial infarction: A longitudinal study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:825–31. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svedlund M, Danielson E, Norberg A. Women’s narratives during the acute phase of their myocardial infarction. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35:197–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein S. Spirituality, denial, and dispositional optimism as related to psychological adjustment in myocardial infarction patients on a coronary care unit. United States: University of Miami; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hadaegh F, Harati H, Ghanbarian A, Azizi F. Prevalence of coronary heart disease among Tehran adults: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:157–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fakhrzadeh H, Bandarian F, Adibi H, Samavat T, Malekafzali H, Hodjatzadeh E, et al. Coronary heart disease and associated risk factors in Qazvin: A population-based study. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghadimi H, Bishehsari F, Allameh F, Bozorgi AH, Sodagari N, Karami N, et al. Clinical characteristics, hospital morbidity and mortality, and up to 1-year follow-up events of acute myocardial infarction patients: The first report from Iran. Coron Artery Dis. 2006;17:585–91. doi: 10.1097/01.mca.0000224419.29186.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajian-Tilaki K, Jalali F. Changing patterns of cardiovascular risk factors in hospitalized patients with acute myocardial infarction in Babol, Iran. Kuwait Med J. 2007;39:243–47. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatmi ZN, Tahvildari S, Gafarzadeh Motlag A, Sabouri Kashani A. Prevalence of coronary artery disease risk factors in Iran: A population based survey. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2007;7:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okhravi M. Causes for pre-hospital and in-hospital delays in acute myocardial infarction at Tehran teaching hospitals. AENJ. 2002;5:21–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson I, Dahlberg K, Ekebergh M. Living with experiences following a myocardial infarction. Eur J Cardiovas Nurs. 2003;2:229–36. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khraim F, Carey M. Predictors of pre-hospital delay among patients with acute myocardial infarction. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:155–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergman E, Malm D, Karlsson J, Berterö C. Longitudinal study of patients after myocardial infarction: Sense of coherence, quality of life, and symptoms. Heart Lung. 2009;38:129–40. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bingham V. The recovery experience for persons with a myocardial infarction and their spouses/partners. United States: The University of Alabama; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sjöström-Strand A, Fridlund B. Women’s descriptions of coping with stress at the time of and after a myocardial infarction: A phenomenographic analysis. Can J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006;16:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walton J. Spirituality of patients recovering from an acute myocardial infarction: A grounded theory study. J Hol Nurs. 1999;17:34–53. doi: 10.1177/089801019901700104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webster R, Thompson D, Mayou R. The experiences and needs of Gujarati Hindu patients and partners in the first month after a myocardial infarction. Eur J Cardiovas Nurs. 2002;1:69–76. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(01)00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiles R. Patients’ perception of their heart attack and recovery: The influence of epidemiological ’’ evidence’’ and personal experience. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1477–86. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)10140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koenig H. Religion, spirituality, and medicine: Application to clinical practice. JAMA. 2000;284:1708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burkhart L, Hogan N. An experiential theory of spiritual care in nursing practice. Qual Health Res. 2008;18:928–38. doi: 10.1177/1049732308318027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee L, Connor K, Davidson J. Eastern and Western Spiritual Beliefs and Violent Trauma: A U.S. National Community Survey. Traumatology. 2008;14:68–76. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doster J, Harvey M, Riley C, Goven A, Moorefield R. Spirituality and cardiovascular risk. J Relig Health. 2002;41:69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edmondson K, Lawler K, Jobe R, Younger J, Piferi R, Jones W. Spirituality predicts health and cardiovascular responses to stress in young adult women. J Relig Health. 2005;44:161–71. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawler K, Younger J. Theobiology: An analysis of spirituality, cardiovascular responses, stress, mood, and physical health. J Relig Health. 2002;41:347–62. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tartaro J, Luecken L, Gunn H. Exploring heart and soul: Effects of religiosity/spirituality and gender on blood pressure and cortisol stress responses. J Health Psychol. 2005;10:753–66. doi: 10.1177/1359105305057311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller J, McConnell T, Klinger T. Religiosity and spirituality: Influence on quality of life and perceived patient self-efficacy among cardiac patients and their spouses. J Relig Health. 2007;46:299–313. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Ironson G, Thoresen C, Powell L, Czajkowski S, et al. Spirituality, religion, and clinical outcomes in patients recovering from an acute myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:501–8. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180cab76c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boston P, Mount B, Orenstein S, Freedman O. Spirituality, religion, and health: The need for qualitative research. Annales CRMCC. 2001;34:368–83. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis L, Hankin S, Reynolds D, Ogedegbe G. African-American spirituality: A process of honoring God, others, and self. J Hol Nurs. 2007;25:16. doi: 10.1177/0898010106289857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiu L, Emblen J, Van Hofwegan L, Sawatzky R, Meyerhoff H. An integrative review of the concept of spirituality in the health sciences. West J Nurs Res. 2004;26:405–28. doi: 10.1177/0193945904263411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research, techniqes and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE publication; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groleau D, Whitley R, Lespérance F, Kirmayer L. Spiritual reconfigurations of self after a myocardial infarction: Influence of culture and place. Health Place. 2010;16:853–60. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. London: Thousand Oaks, Sage publication; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Streubert H, Carpenter D. Qualitative Research in Nursing. 4nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Walks Co.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camp P. Having faith: Expriencing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiovas Nurs. 1996;10:55–64. doi: 10.1097/00005082-199604000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raholm MB. Weaving the fabric of spirituality as experienced by patients who have undergone a coronary bypass surgery. J Holist Nurs. 2002;20:31–47. doi: 10.1177/089801010202000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassankhani H, Taleghani F, Mills J, Birks M, Francis K, Ahmadi F. Being hopeful and continuing to move ahead: Religious coping in iranian chemical warfare poisoned veterans, a qualitative study. J Relig Health. 2010;49:311–21. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9252-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rassool G. The crescent and Islam: healing, nursing and the spiritual dimension. Some considerations towards an understanding of the Islamic perspective on caring. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1476–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johansson I, Swahn E, Strömberg A. Manageability, vulnerability and interaction: A qualitative analysis of acute myocardial infarction patients’ conceptions of the event. Eur J Cardiovas Nurs. 2007;6:184–91. doi: 10.1016/J.EJCNURSE.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenfeld AG, Gilkeson J. Meaning of illness for women with coronary heart disease. Heart Lung. 2000;29:105–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lesneski L. Factors influencing treatment delay for patients with acute myocardial infarction. Appl Nurs Res. 2010;23:185–90. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKinley S, Dracup K, Moser DK, Ball C, Yamasaki K, Kim CJ, et al. International comparison of factors associated with delay in presentation for AMI treatment. Eur J Cardiovas Nurs. 2004;3:225–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zegrean M, Fox-Wasylyshyn S, El-Masri M. Alternative coping strategies and decision delay in seeking care for acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovas Nurs. 2009;24:151–5. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000343561.06614.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenfeld AG, Lindauer A, Darney BG. Understanding treatment-seeking delay in women with acute myocardial infarction: Descriptions of decision-making patterns. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14:285–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Isaksson R, Holmgren L, Lundblad D, Brulin C, Eliasson M. Time trends in symptoms and prehospital delay time in women vs. men with myocardial infarction over a 15-year period. The Northern Sweden MONICA Study. Eur J Cardiovas Nurs. 2008;7:152–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.East L, Brown K, Twells C. ‘Knocking at St Peter’s door’. A qualitative study of recovery after a heart attack and the experience of cardiac rehabilitation. Primary Health Care Res Devel. 2004;5:202–10. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walton J. Discovering meaning and purpose during recovery from an acute myocardial infarction. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2002;21:36–43. doi: 10.1097/00003465-200201000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halligan P. Caring for patients of Islamic denomination: Critical care nurses’ experiences in Saudi Arabia. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:1565–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jalali B. Iranian Families. In: McGoldrick M, Giordano J, GarciaPreto N, editors. Ethnicity and family therapy. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Omeri A. Culture care of Iranian immigrants in new south Wales, Australia: Sharing transcultural nursing knowledge. J Transcult Nurs. 1997;8:5–16. doi: 10.1177/104365969700800202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Triandis HC, Suh EM. Cultural influences on personality. Ann Rev Psychol. 2002;53:133–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarookhani B. Introduction on family sociology. 3rd ed. Tehran: Soroosh; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davidson J. Spirituality and medicine: Science and practice. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:388–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Well S, Kolk A. Social support and cardiovascular responding to laboratory stress: Moderating effects of gender role identification, sex, and type of support. Psychol Health. 2008;23:887–907. doi: 10.1080/08870440701491381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mauk K, Schmidt N. Spiritual care in nursing practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams Wilkins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rankin EA, Delashmutt MB. Finding spirituality and nursing presence: The student’s challenge. J Holist Nurs. 2006;24:282–8. doi: 10.1177/0898010106294423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fontana D. Psychology, religion, and spirituality. Oxford: BPS Blackwell; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kelcourse F. Prayer and the soul: Dialogues that heal. J Relig Health. 2001;40:231–41. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Asadi-Lari M, Goushegir S, Madjd Z, Latifi N. Spiritual care at the end of life in the Islamic context, a systematic review. Iranian J Cancer Prev. 2008;1:63–7. [Google Scholar]

- 59.McSherry W. Spirituality in nursing practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. [Google Scholar]