Abstract

Neurofibromas are benign tumours arising from the Schwann cells of peripheral nerves. They usually occur on the limbs and rarely present at other sites such as the thyroid gland. Lesions associated with the thyroid are usually benign but should be closely followed up. When the presence of a plexiform neurofibroma in the thyroid gland is confirmed by radiological investigations, total thyroidectomy is the treatment of choice because of the substantial risk of malignant transformation. This case report details a rare case of thyroid plexiform neurofibroma in a young female patient with known Von Recklinghausen disease.

Background

We believe this case is interesting given both the rarity of the condition and the dilemma posed in treating a young patient with relatively major surgery without a tissue diagnosis.

Case presentation

A 14-year-old girl was admitted to our surgical unit with a palpable solid nodule on the left lobe of the thyroid gland. The patient and her family were not sure how long the nodule had been present but stated that it had slowly enlarged in the preceding weeks. The patient was diagnosed with neurofibromatosis (NF) type 1 at the age of 2 years, when her first cutaneous lesions appeared on her back. Her mother, who also suffered with NF type 1, died at the age of 36 when the patient was 7 years old. At the age of 12, she underwent spondylosyndesis because of a neurinoma of the spinal cord. She also had a partial removal of the right breast due to a fibroma 3 years prior to this admission. She had no developmental issues and was otherwise in good health.

On palpation the nodule was painless, firmly attached in the thyroid gland and followed the movement of the gland on swallowing. No skin alteration or ulceration was observed in the area of the lesion. Multiple cafe-au-lait spots over the back abdomen were present and multiple cutaneous skin lesions consistent with dermal neurofibromas were noted on both the trunk and limbs. A multiple disciplinary team consisting of endocrine surgeons, orthopaedics, neurologists, ophthalmologists and radiologists was convened to discuss management options for the patient given the rare nature of the disorder.

Neurological examination was essentially normal. The ophthalmological examination found normal visual fields, normal acuity and did not reveal the presence of a hamartoma on the iris, a characteristic feature of the disease. Musculoskeletal deformities such as kyphosis and scoliosis were not found at the present time and she had no skull abnormalities.

Investigations

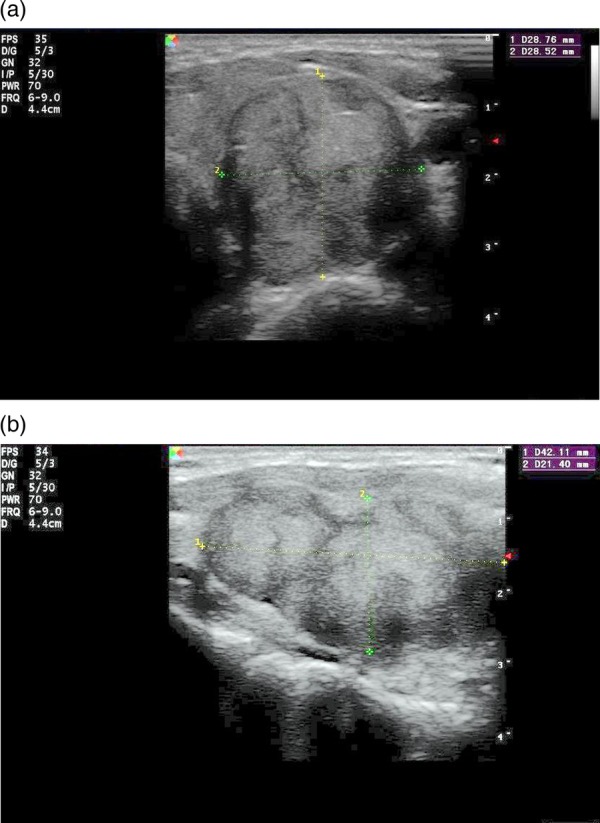

On biochemical analysis, the patient was euthyroid, with serum levels of free T4: 14.2 ng/mL, free T3: 3.9 pg/mL and thyroid stimulating hormone: 2.8 ng/mL. The anti-serum thyroglobulin was 92 ng/mL and the anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody level was 298.8 ng/mL. The complete blood count, serum biochemistry markers, calcitonin, as well as the serum calcium and parathyroid levels were normal. The thyroid ultrasonography revealed a 44×30×26 mm solid, hyper echoic, multinodular lesion with small amount of calcification in the left lobe (figure 1A,B). The right lobe appeared to be normal. These findings were present on the previous ultrasound scan of the thyroid gland a year ago where the dimensions of the nodule were 41×26×23 mm. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) was not diagnostic since no thyroid cells were aspirated probably because of the solid nature of the tumour. Full body MRI was unremarkable except for the features outlined above.

Figure 1.

(A) Sagittal view—plexiform type neurofibroma with three adjacent nodules in a solid thick-walled nodule. (B) Transverse view: 4.4 cm in diameter multinodular nodule in the left lobe.

Owing to the absence of a histological diagnosis and the fact that a malignant lesion could not be excluded the board reconvened to discuss potential management strategies. They decided, on balance, that total thyroidectomy should be offered to the patient. Following detailed discussions with both the patient and her family they gave consent for surgery.

Differential diagnosis

Papillary, medullary, follicular and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, benign thyroid cyst or adenoma, neurofibroma of the thyroid gland.

Treatment

The patient underwent total thyroidectomy without complication. Of note during the procedure, no enlarged paratracheal lymph nodes were found and the solid nodule was not exerting external compression upon the trachea. Histopathology report revealed the presence of three nodules firmly attached to each other. The maximum diameter of the nodules was 1.7, 2.0 and 2.5 cm. They had grown in a longitudinal axis giving the ‘bag of worms’ appearance characteristic of plexiform neurofibromas.

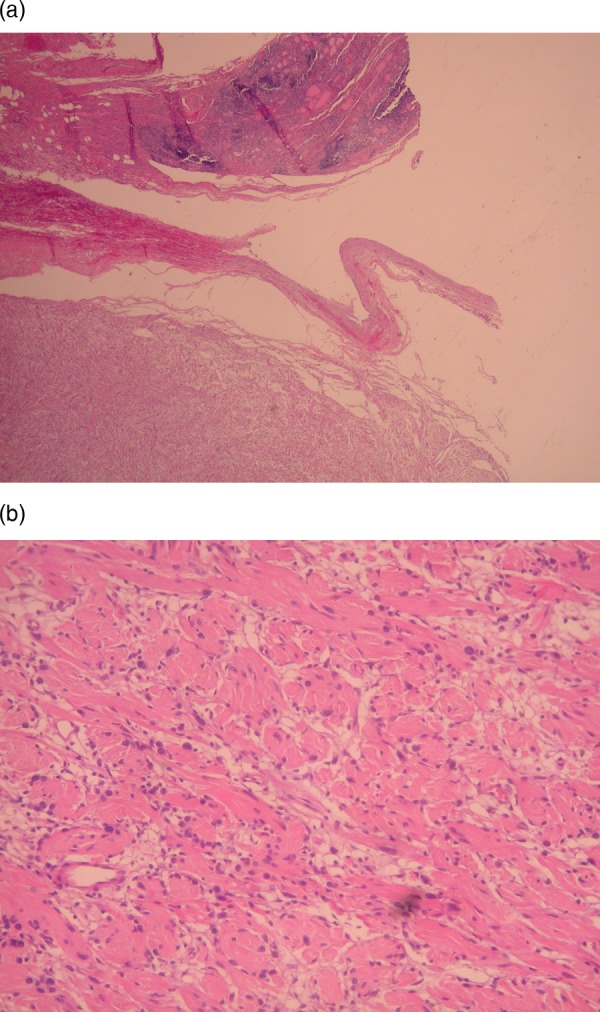

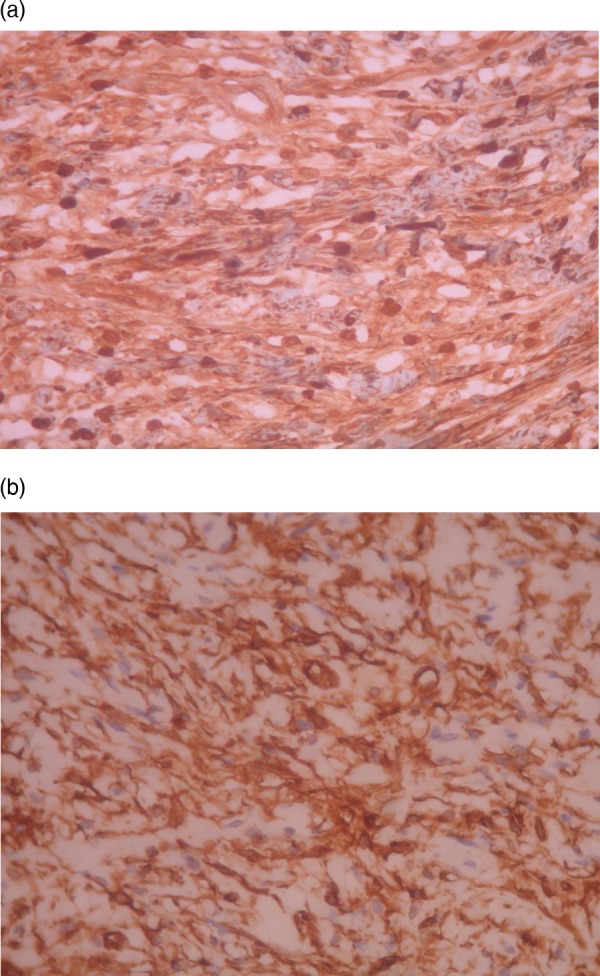

The use of H&E stain showed typical microscopic features (figure 2A,B) of plexiform neurofibromas, without elements of malignancy, juvenile thyroiditis or multinodular goitre. Immunochemistry showed that the tumour cells of the lesion expressed S100 and CD34 (figure 3A,B).

Figure 2.

(A) Section from the neurofibroma margins with the thyroid parenchyma, which shows lesions of lymphocytic thyroiditis. (H&E stain low magnification). (B) Typical microscopic features of neurofibroma (H&E stain high magnification).

Figure 3.

(A) Tumour cells positive for S100 protein (immunostain high magnification). (B) Tumour cells positive for CD34 (immunostain high magnification).

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperatively her convalescence was uneventful and she was discharged back home 7 days after the procedure. To date, a year after the operation, she remains well and subsequent follow-up MRI scans have not shown local recurrence or evidence of metastatic disease.

Discussion

NF type 1 is an autosomal dominant inherited disorder caused by a tumour suppressor gene which is located on the 17q11.2 chromosome.1 The diagnostic criteria for positive diagnosis of NF type 1, as set by the National Institute of Health,2 3 include the following: six or more café-au-lait spots over 5–15 mm in greatest diameter; two or more neurofibromas of any type or one plexiform neurofibroma; freckling in the axillary or in inguinal regions; optic glioma; two or more lisch nodules (iris hamartomas); a distinctive osseous lesion; a first-degree relative with NF-1 by the above criteria; discovered mutations of the NF1 gene, which is located at 17q11.2 chromosome.4 Two of the seven mentioned criteria are required for the positive diagnosis.

Plexiform neurofibromas are reported to occur in about 27% of patients with type I NF.5 They appear to be congenital and almost 50% of them appear on the head, neck, face and larynx. They seem to develop in early childhood and can cause both local pressure effects on surrounding structures or malignant disease. Histologically, they are peripheral nerve sheath tumours containing all elements of the peripheral nerve and are characterised by an increase in endoneurial matrix with separation of nerve fascicles and proliferation of Schwann cells, resulting in a ‘bag of worms’ appearance.2 Plexiform neurofibromas are categorised to three different types based on the appearance of their growth pattern as displayed by MRI scanning: superficial, displacing and invasive. The superficial subtype is confined to the upper layer of skin and does not involve major nerves. Given the superficial nature of these tumours, surgical resection is generally uncomplicated and has a higher rate of clear resection margins.6 Displacing plexiform neurofibromas exert local pressure effects on surrounding structures that may make surgical resection difficult. The invasive subtype involves major nerves whereby the tumour diffuses through multiple tissue layers and invades nearby structures, again, making surgical resection complicated. Malignant plexiform neurofibromas occur in 2–10% of patients with NF type 1 compared with an incidence of 0.001% in the general population.7

An evaluation of 46 NF type1 patients by Iannicelli et al,8 found ultrasound scanning to be the first-line imaging modality of choice for superficial neurofibromas. Subsequent MRI aids in the evaluation of NF associated nerve sheath tumours in order to evaluate the location of the lesion, the relationship with the adjacent tissues and the margins of the lesion. It could be also useful for deep multiloculated neurofibromas and for preoperative staging of the disease.9 Plain radiographs may be indicated for lesions of the thorax as an initial investigation. CT can also be used for lesions of the head, neck, thorax and abdomen particularly if displacement of major vessels is suspected or access to MRI is limited. Larger tumours in the neck may cause vascular insufficiency, nerve palsies and airway obstruction because of local pressure effects.10 Both CT and MRI will be useful in this setting. Ciardi et al11 reported a case of a patient with a solid neurofibroma that was adherent to the lower margin of the thyroid gland which extended retrosternally to the anterior mediastinum. Although surgical removal of these tumours will be desirable they pose significant anaesthetic risk due to the potential for complete airway obstruction and should be managed in specialist centres.

FNA is required for definitive diagnosis of plexiform neurofibroma but its role in the investigation of other lesions related to NF type 1 such as schwannomas is rather controversial.12 Histological examination may reveal plexiform neurofibroma alone or in combination with either papillary or follicular carcinoma.13

In our case ultrasound-guided FNA finding was inconclusive, since the capsule of the lesion was solid and multiple attempts at aspiration did not yield a sample suitable to provide a histological diagnosis. Though total thyroidectomy represents a treatment option with significant risks, the patient opted for surgery given the potential for malignant spread. Decisions relating to rare disorders are often difficult as there is less evidence available with which to make informed treatment recommendations to the patient. This patient has had a malignant tumour removed successfully but there still remains a chance that the tumour may recur.

The characteristic finding in our case was the presence of an isolated plexiform neurofibroma in the left thyroid lobe without local invasion or metastatic spread. In a retrospective review in 39 patients with NF type 1 and plexiform neurofibromas of the head and neck, there are no reports of any patient with an isolated plexiform neurofibroma of the thyroid gland.10

Management of plexiform neurofibromas is primarily surgical since these tumours do not respond to radiotherapy or chemotherapy. Surgical management should aim for total resection of the lesion since subtotal resection or debulking is associated with higher rates of recurrence. A retrospective review by Needle et al14 reported a 20% recurrence rate in total resection and a 45% recurrence in subtotal resection over a 20-year study period with 54% of all patients free from recurrence over the review period. Jeffrey et al, in another retrospective review, report a 25% recurrence after resection of small tumours and 100% recurrence in massive tumours.10 Although this patient had a satisfactory total resection, a substantial risk of recurrence remains and she should have regular follow-up and surveillance to identify possible recurrence as swiftly as possible.

Plexiform neurofibromas represent a rare cause of thyroid mass. When they present in the thyroid parenchyma without evidence of local invasion, total thyroidectomy without central compartment dissection is the treatment of choice.

Learning points.

Plexiform neurofibroma is a rare cause of thyroid mass.

Treatment of choice should be total thyroidectomy, since malignant transformation is possible.

Fine needle aspiration can be inconclusive for the correct diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1.

Footnotes

Contributors: IK, TD and BP performed the operation. All the four authors participated in the design, analysis, writing the case report and also correction and revision of the article prior to submission.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cawthon RM, Weiss R, XU GF, et al. A major segment of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene: cDNA sequence, genomic structure and point mutations. Cell 1990;2013:193–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huson SM, Hughes, RAC. The neurofibromatoses: a pathogenetic and clinical overview. London: Chapman & Hall, 1994:1.3.2:9 [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: neurofibromatosis. Bethesda, Md, USA, July 13–15, 1987. Neurofibromatosis 1988;1:172–8. [PubMed]

- 4.Wenig BM. Atlas of head and neck pathology. Philadelphia:WB Saunders, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Power KT, Giannas J, Babar Z, et al. Management of massive lower limb plexiform neurofibromatosis—when to intervene? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2007;2013:807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedrich RE, Schmelzle R, Hartmann M, et al. Subtotal and total resection of superficial plexiform neurofibromas of face and neck. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2005;2013:55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferner RE, O'Doherty MJ. Neurofibroma and schwannoma. Curr Opin Neurol 2002;2013:679–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iannicelli E, Rossi G, Almberger M, et al. Integrated imaging in peripheral nerve lesions in type 1 neurofibromatosis. Radiol Med 2002;2013:332–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murovic J, Kim D, Kline D. Neurofibromatosis-associated nerve sheath tumors. Neurosurg Focus 2006;2013:E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wise J, Cryer J, Belasco J, et al. Management of head and neck plexiform neurofibromas in pediatric patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;2013:712–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciardi A, Pecorella I, Trombetta G, et al. An unusual case of neurofibroma of the thyroid capsule. Patholo Oncol Res 1997;2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anagnostouli M, Piperingos G, Yapijakis C, et al. Thyroid gland neurofibroma in a NF1 patient. Acta Neurol Scand 2002;2013:58–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koksal Y, Sahin M, Koksal H, et al. Neurofibroma adjacent to the thyroid gland and a thyroid papillary carcinoma in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1: report of a case. Surg Today 2009;2013:884–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Needle MN, Cnaan A, Dattilo J, et al. Prognostic signs in the surgical management of plexiform neurofibroma: the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia experience, 1974–1994. J Pediatr 1997;2013:678–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]