Summary

Stem cell-niche interactions have been studied extensively with regard to cell polarity and extracellular signaling. Less is known about the way in which signals and polarity cues integrate with intracellular structures to ensure appropriate niche organization and function. Here we report that nuclear lamins function in the cyst stem cells (CySCs) of Drosophila testis to control the interaction of CySCs with the hub. This interaction is important for regulation of CySC differentiation and organization of the niche that supports the germline stem cells (GSCs). Lamin promotes nuclear retention of phosphorylated ERK in the CySC lineage by regulating the distribution of specific nucleoporins within the nuclear pores. Lamin-regulated nuclear EGFR signaling in the CySC lineage is essential for proliferation and differentiation of the GSCs and the transient amplifying germ cells. Thus, we have uncovered a role for the nuclear lamina in integration of EGF signaling to regulate stem cell niche function.

Keywords: lamin, nucleoporin, EGFR, germline development, stem and progenitor cells

Introduction

Many human diseases can be attributed to the disruption of tissue homeostasis. The maintenance and differentiation of stem and progenitor cells, regulated by the niche they reside in, play important roles in supporting tissue homeostasis. Studies in different systems have shown that both extracellular signaling and cell polarity regulate the communications between the stem/progenitor cells and their niches formed by either terminally differentiated tissues or by continuously self-renewing cells. However, it remains unclear how a given signaling pathway or polarity cue is integrated with the nuclear structure to regulate the organization and maintenance of any niche.

The nuclear lamina, which contains the type V intermediate filament proteins (the A- and B-type lamins), forms multiple contacts in the nucleus that link chromatin, nuclear envelope proteins, and nuclear pores to cytoskeleton (Dechat et al., 2008; Simon and Wilson, 2011; Smythe et al., 2000). It therefore represents a potential structural node that could couple cell signaling and polarity to cell morphogenesis. Consistently, lamins have been implicated in proper development of at least some organs (Coffinier et al., 2010; Coffinier et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011; Sullivan et al., 1999; Vergnes et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2011). Studies using tissue culture cells and cell free assays in the past several decades have shown that lamins could regulate diverse cell functions (Bank and Gruenbaum, 2011; Dechat et al., 2008; Finlan et al., 2008; Goodman et al., 2010; Guelen et al., 2008; Kumaran and Spector, 2008; Ma et al., 2009; Peric-Hupkes et al., 2010; Reddy et al., 2008; Tsai et al., 2006; Zheng, 2010). The relevance for these functions in the context of development and tissue homeostasis has, however, remained unknown.

Since the discovery that many mutations in A-type lamins cause human diseases, the effort in studying the disease mechanism has grown exponentially in recent years. Whereas it is critical to use patient samples and animal models to establish how changes in lamins cause human diseases, understanding the basic mechanism that lamins use to regulate organism development and tissue maintenance will also contribute toward the dissection of the disease mechanism. Unfortunately, despite of the existence of lamin mutations and deletions in model organisms such as the mouse, Drosophila, and C. elegans, the role of lamins in the context of development is still poorly understood.

We reasoned that although many functions have been assigned to lamins, a given cell or tissue type may only use a subset of these functions during certain stages of its differentiation, morphogenesis, and homeostasis. It is therefore important to define such cell- or tissue-specific functions. The Drosophila testis is one of the best-characterized systems to study the interaction between stem/progenitor cells and their niches. Well-defined somatic cells form the niche to support the germline stem cells (GSCs) and the transient amplifying (TA) germline progenitors in the testis. While the post mitotic hub cells and the cyst stem cells (CySCs) provide the somatic niche for GSCs, the post-mitotic cyst cells differentiated from the CySCs provide the support for the TA germ cells. Cross signaling among the hub cells, GSCs, and CySCs ensures proper maintenance and differentiation of GSCs and CySCs (Davies and Fuller, 2008; de Cuevas and Matunis, 2011; Fuller and Spradling, 2007). For example, EGFR signaling in the CySC lineage controls the development of the GSC lineage during spermatogenesis (Kiger et al., 2000; Parrott et al., 2012; Sarkar et al., 2007; Tran et al., 2000). Additionally, the hub-cell secreted ligand induces JAK-STAT signaling in CySCs, which is needed for proper interactions of the GSCs and CySCs with the hub cells (Cherry and Matunis, 2010; Issigonis et al., 2009; Kiger et al., 2001; Leatherman and Dinardo, 2010; Tulina and Matunis, 2001).

Using the Drosophila testis as a model system we have uncovered a role of lamins in the CySC lineage that form the niche to support the proper proliferation and differentiation of the GSCs and TA germline progenitors.

Results

Lamin-B is required for Drosophila spermatogenesis

The post-mitotic hub cells at the tip of the testis form the niche that directly contacts both the GSCs and CySCs to support their self-renewal and undifferentiated states (Gonczy and DiNardo, 1996; Hardy et al., 1979). Each GSC is encapsulated by a pair of CySCs, and the crosstalk between CySC and GSC is essential for the maintenance and differentiation of both types of stem cells. As the GSC divides to give rise to a progenitor cell called the gonialblast and a new GSC, the pair of CySCs also divides to produce a pair of new CySCs and the differentiating cyst cell pair, which enclose the gonialblast (Figure 1A). As each gonialblast divides and differentiates to form spermatogonia followed by spermatocytes, the cyst cell pair stop dividing, and they undergo significant morphological changes, which allow the cyst cells to enclose the TA germline progenitors and spermatocytes (Figure 1A) (de Cuevas and Matunis, 2011; Fuller and Spradling, 2007; Zoller and Schulz, 2012; Lim and Fuller, 2012).

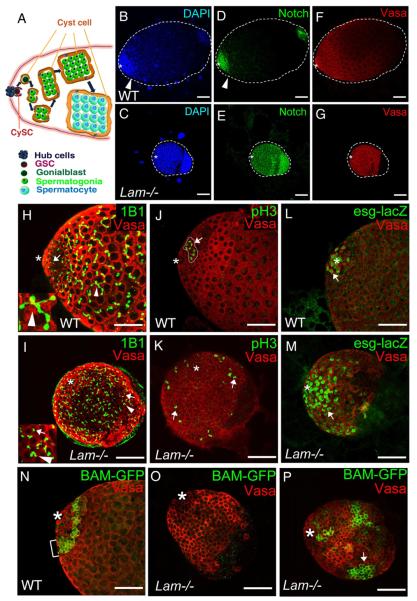

Figure 1. Effects of LAM deletion on the differentiation of GSCs and the transit-amplifying germ cells in 3rd instar larvae (L3) male gonads.

A. The hub cells form the niche for both GSCs and CySCs. The asymmetric division of a GSC produces a new GSC and a gonialblast that displace away from the hub along with the pair of cyst cells produced through the asymmetric divisions of a pair of CySCs. Further differentiation of gonialblasts involves spermatogonial mitosis (transient amplification) followed by the growth of spermatocytes, spermatocyte meiosis, and the formation of sperm bundles (not shown). Thick arrows indicate the progression of differentiation and development.

B–G. Defects of germ cell differentiation in Lam-null L3 male gonads. DAPI (B and C), Notch (D and E), and Vasa (F and G) staining of wild-type (B, D, F) and LamD395/Df(2L)cl-h1 (Lam−/−) (C, E, G) L3 male gonads. Vasa (red) labels germ cells. Notch (green) labels GSCs, gonialblasts, and spermatogonia. Arrowheads mark the transition between spermatogonia and spermatocytes in the wild-type gonad, which is missing in the Lam-null gonads.

H and I. L3 Male gonads labeled by the monoclonal antibody 1B1, which stains the spectrin in spectrosomes and fusomes (green). The wild-type gonad (H) contained both spherical spectrosomes (in GSCs, gonialblasts, and two-cell stage spermatogonia, arrow) and branching fusomes (in spermatogonia and spermatocytes, arrowhead), while the Lam-null gonad (I) contained mostly spectrosome-like structures (arrow) and a few poorly branched fusomes (arrowhead). The inset in H shows an enlarged area with the arrow pointing to a branched fusome. The inset in I show an enlarged area with the arrow and arrowhead pointing to a spectrosome and a poorly branched fusome, respectively.

J and K. A wild-type L3 male gonad (J) contains a cyst of 8 pH3+ germ cells (arrow) that is close to the hub, whereas most pH3+ germ cells in the Lam-null gonad (K) appear as singlets or pairs (arrows) and many of them are far away from the hub (asterisk).

L and M. Labeling of Hubs (asterisks), GSCs, and gonialblasts by escargotM5-4-LacZ (green) revealed the accumulation of undifferentiated GSCs or gonialblasts (arrows) in the Lam-null male gonad (M) compared to the wild-type control (L).

N–P. Labeling of spermatogonia by BAM-GFP expression indicates the expected localization of BAM-GFP+ cells in wild-type (N) close to the hub (asterisks). In the Lam-null gonads, 52.2% (n=23) do not have BAM-GFP+ cells (O), while the remaining gonads (P) contain large clusters of BAM-GFP+ cells that are displaced away from the hub. The arrow in P marks a cluster of more than 16 BAM-GFP+ germ cells. Scale bars, 50μm.

Drosophila expresses one A- and one B-type lamins called LAMC and Lamin Dm0 (LAM) encoded by LamC and Lam genes, respectively. We first analyzed the role of LAM during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Flies harboring the Lam-null allele as LamD395/Df(2L)cl-h1 transheterozygotes die during larval and pupal stages with ~6% `escapers' that eclose (Munoz-Alarcon et al., 2007). The surviving adults appeared grossly normal but were male and female sterile. Male sterility could be caused by defects in spermatogenesis. We first focused on the male gonads from the third instar larvae (L3) using DAPI staining. Since the early germ cells (including GSCs, gonialblasts, and spermatogonia) have more condensed chromatin than the differentiated spermatocytes, their nuclei exhibit brighter DAPI staining than those of the spermatocytes. Thus DAPI can be used to assess different differentiation stages of the germline (Kiger et al., 2000; Tran et al., 2000). As expected, wild-type L3 male gonads consisted of both early germ cells and differentiated spermatocytes as judged by strong and weak DAPI staining, respectively (Figure 1B) (Kiger et al., 2000; Tran et al., 2000). By contrast, most Lam-null male gonads were small and were filled with DAPI-bright early germ cells with a near complete lack of differentiated spermatocytes and spermatids (Figure 1C). Further analyses using antibodies to Notch and Vasa, which label early stage germ cells and all stage germline cells (Kiger et al., 2000), respectively, confirmed that Lam-null male gonads were indeed filled with Notch+/Vasa+ early germ cells (Figure 1D–G).

Next, we used the antibody 1B1 to label the spectrosomes and fusomes, which are spectrin rich structures found in GSCs, gonialblasts, spermatogonia, and spermatocytes. A single round spectrosome is found next to the centrosome in GSCs and gonialblasts. As a gonialbast undergoes repeated mitosis and incomplete cytokinesis, the spectrosome transforms into an increasingly branched structure called the fusome that connects the sister spermatogonia and spermatocytes through the cleavage furrows in a cyst (Hime et al., 1996). Therefore the shape of spectrosomes and fusomes can be used as a marker for the early and later germ cells, respectively. We found that wild-type L3 male gonads contained both round spectrosomes and branched fusomes, whereas Lam-null gonads were filled with early germ cells containing mostly spectrosome-like structures and poorly branched fusome-like structures (Figure 1H and 1I).

To further analyze the germline cells, we used antibodies to phosphorylated histone H3 (pH3) to label the dividing germ cells. Since germ cells in a given cyst divide synchronously, each pH3+ cyst may contain 1, 2, 4 or 8 germ cells. We found that in wild-type gonads 52.2% of the pH3+ cysts contained 4 or 8 germ cells with the remaining containing 1 or 2 germ cells, and all these cysts were localized near the hub (total pH3+ cysts analyzed, 46) (Figure 1J). By contrast, of 538 pH3+ cysts analyzed in the Lam-null gonads only 2.4% contained 4 or more germ cells with the remaining containing 1 or 2 germ cells, and these pH3+ cells were distributed throughout the gonads (Figure 1K). Next, we analyzed male gonads using the escargot-lacZ reporter line M5-4 that labels GSCs and gonialblasts. As expected, the escargot-lacZ+ GSCs and gonialblasts surrounded the hub in all wild-type gonads analyzed (Figure 1L) and each gonads contained between 5 to 12 escorgot-lacZ+ germ cells (total gonads analyzed, 14). In Lam-null gonads, however, we found 25 to 157 escargot-lacZ+ germ cells per gonads (total gonads analyzed, 12) and many of these cells are far away from the hub (Figure 1M).

We also analyzed the process of GSC differentiation using Bam-GFP (a reporter for spermatogonia). The wild-type spermatogonia cysts formed a tight Bam-GFP positive band close to the hub as expected (Figure 1N). By contrast, 52.2% (n=23) of Lam-null male gonads contained spermatogonia (Figure 1O), while the remaining contained large clusters of Bam expressing germline cells fail to undergo further differentiation (Figure 1P). No or very few spermatocytes were found in all lam-null gonads analyzed.

Since ~6% of Lam-null (LamD395/Df(2L)cl-h1) pupae survive to adulthood, we were able to analyze the adult testis. Compared to wild type, the 2-day old Lam-null testes (11 out of 11) were very small and were filled with DAPI-bright undifferentiated germ cells (Figure 2A and 2E). Using antibodies to Vasa, LAM, and Traffic Jam (TJ, a transcription factor labeling the nuclei of hub cells, CySCs, and early cyst cells) (Li et al., 2003), we detected LAM in both the germline and soma in the wild-type but not in the Lam-null testis as expected (Figure 2A–H). The above analyses show that lamin-B is required for the development of Drosophila testes.

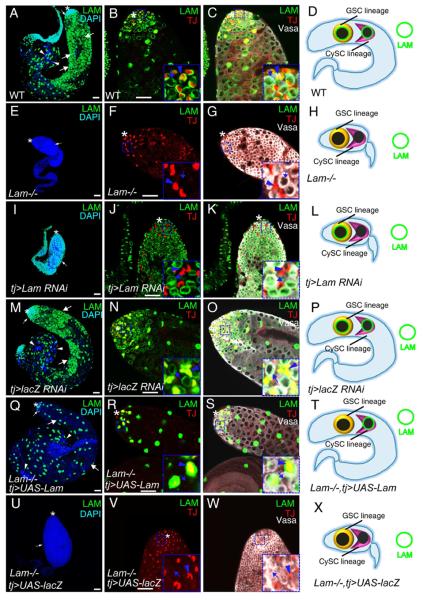

Figure 2. LAM functions in the CySC lineage to support the differentiation of GSCs and the transit-amplifying germ cells.

A–H. Whole-mount testes from 2-day old wild-type and Lam-null animals stained with DAPI and antibodies to LAM, TJ (the CySC lineage), and Vasa (the germline). The tip of wild-type (A) and Lam-null (D) testes are enlarged in B&C and F&G, respectively. C and G show the merge of triple color label of LAM, TJ, and Vasa of the same testes shown in B and F, respectively. Small white arrows in A and E, early germ cells. Large white arrows and arrowheads in A show spermatocytes and sperm bundles, respectively. Insets in B&C and F&G show enlarged areas with blue arrows and arrowheads indicating Vasa+ germ cells and TJ + cyst cells, respectively. D and H illustrate the nuclear LAM (green circle) status in the GSC and CySC lineages in wild-type (D) and Lam-null (H) testes. For clarity, only one GSC and one CySC are shown. Lam-null in both lineages leads to the formation of small testes as shown in H.

I–P. Testes with the CySC lineage depletion of LAM (I–L) using the tj-Gal4 driven Lam RNAi allele (v45635), but not the control LacZ RNAi (M–P), phenocopied defects seen in Lam-null testes (see E–H). The tip of the testis treated by Lam RNAi (I) or control RNAi (M) is enlarged in J&K and N&O, respectively. K and O show the merge of triple color label of LAM, TJ, and Vasa of the same testes shown in J and N, respectively. Blue arrows and arrowheads in the enlarged insets in J&K and N&O indicate Vasa+ germ cells and TJ+ cyst cells, respectively. L and P illustrate the testes with cyst cell depletion of LAM by RNAi (L), but not contol RNAi (P), phenocopied the defects seen in Lam-null testes.

Q–X. Expression of Lam cDNA in the CySC lineage using tj-Gal4 (Q–T), but not control LacZ cDNA (U–X), fully rescued the testis defects and male fertility in the Lam-null mutants. The tip of a wild-type (Q) and Lam-null (U) testes are enlarged in R&S and V&W, respectively. S and W show the merge of triple color label of LAM, TJ, and Vasa of the same testes in R and V, respectively. The enlarged insets in R&S and V&W show Vasa+ germ cells (lack LAM, blue arrows) and TJ+ cyst cell (LAM+ in R&S or LAM− in V&W, blue arrowheads). T and X illustrate that Lam cDNA expression, but not the control LacZ cDNA, in the CySC lineage is sufficient for rescuing the testis defects in Lam-null mutants.

Asterisks, hubs. Scale bars, 50μm. See also Figure S1 and Table S1.

Lamin-B functions in the CySC lineage to support the differentiation of GSCs and the transit-amplifying germ cells

To further understand whether lamin-B functions in the germline or in the soma, we used cell-type specific RNAi (Table S1) to knockdown LAM. We found that only depleting LAM in the CySC lineage using tj-Gal4-mediated RNAi caused defects in GSC differentiation (Figure 2I–P) similar to those seen in Lam-null testes (compare to Figure 2A–H). Importantly, using cell-type specific Gal4 to express Lam cDNA in the germline lineage, hub cells, or CySC lineage, we found that only the CySC lineage-specific expression of LAM fully rescued GSC differentiation defects (Figure 2Q–X) and male fertility (26 out of 26 testes analyzed) in Lam-null survivors (Table S1). Additionally, the germline mitotic clones of LamD395 homozygous produced cysts containing differentiating spermatocytes (Figure S1) and spermatids (not shown). Thus, LAM is required in the CySC lineage but is dispensable in both the germline and the hub cells.

Lamin-B functions in CySCs to ensure proper interactions of CySCs and GSCs with the hub

Although both CySCs and GSCs interact with the post mitotic hub cells, the pair of CySCs surrounding each GSC only contact the hub through the long and thin cellular protrusions with their nuclei displaced away from the hub and appearing juxtaposed at the base of the GSCs (Figure 3A and 3B) (Issigonis et al., 2009; Tarayrah et al., 2013). Using Zfh-1, a transcription factor strongly expressed in the nuclei of CySCs and weakly express in the hub and early cyst cells (Leatherman and Dinardo, 2008), we found that comparing to the wild-type L3 male gonads, the nuclei of many CySCs in Lam-null gonads were positioned adjacent to the hub cells (Figure 3C and 3E). A similar phenotype was observed in tj-driven Lam RNAi L3 male gonads (Figure 3D and 3E) in which LAM was depleted only in the CySC lineage. We found that the total numbers of Zfh-1 positive CySC lineage cells were similar among wild-type control (32.5 ±5.5, n=13), tj-driven LacZ RNAi control (31.9 ±2.1, n=14), Lam-null (34.6 ±6.2, n=17), and tj-driven Lam RNAi (35.1±8.1, n=18, Student T test p>0.05) gonads. Thus LAM regulates the localization of CySCs within the niche but not their proliferation.

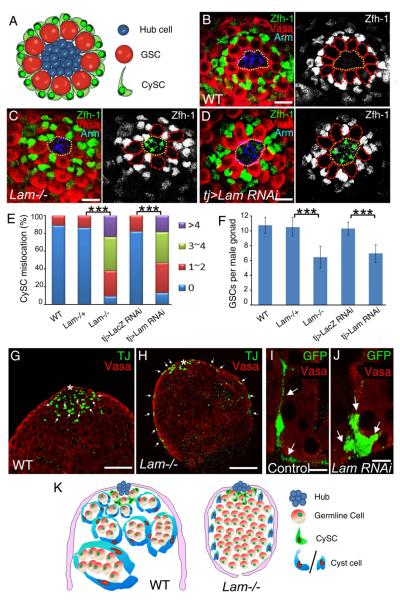

Figure 3. LAM regulates CySC localization and cyst cell morphogenesis A.

A cartoon of the testis niche illustrating the organization of GSCs and CySCs with respect to the hub cells. In wild-type testes, Zfh-1-expressing CySCs surround GSCs. The thin cellular protrusions of CySCs contact the hub with the nuclei localized at the base of the GSCs away from the hub.

B–D. Immunostaining using antibodies against Drosophila beta-catenin (Arm, blue), Vasa (red), and Zfh-1 (green or white) in wild type (B), Lam-null (C), and Tj>Lam RNAi L3 male gonads (D). Green arrows point to the Zfh-1-expressing CySCs with their nuclei localized close to the hub in C and D, while such kind of close localization is not seen in the control testis (B). The hubs are outlined by yellow dotted lines, while GSCs are outlined by red dotted lines in the images with only Zfh-1 staining. Scale bars, 10μm.

E. Quantification of the percentage of L3 male gonads with mis-localized CySCs as judged by the close proximity of the Zfh-1+ nuclei to the hub as seen in C and D. The colored bars indicate the number of CySCs showing mislocalization in each hub. LAM-null (n=36) and tj>LAM RNAi (n=36) L3 male gonads exhibit a significant increase of mis-localized CySCs compared to the wild type (n=27), Lam heterozygous (n=31), or LacZ RNAi (n=28) controls. ***, p<0.001, Wilcoxon Two Sample Tests.

F. LAM-null (n=21) and tj>LAM RNAi (n=23) L3 male gonads exhibit a significant decrease in the number of GSCs associated with the hub compared to the wild type (n=16), Lam heterozygous (n=18), or LacZ RNAi (n=17) controls. ***, p<0.001, Student T tests. Error bars, standard deviation (SD).

G and H. The cross section views of L3 male gonads. Comparing to wild type, the TJ+ (green, indicated by white arrows) cyst cells in the Lam-null gonad were displaced away from the early germ cells (red, Vasa) near the hub with many cyst cells mislocalized to the surface of the gonads. Asterisks, hubs. Scale bar, 50μm.

I and J. The use of the Flp-out RNAi strategy to specifically mark individual cyst cells by GFP. UAS-GFP expressed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus labeled the control (I) and Lam-RNAi (J) cyst cells. Antibodies to GFP (green) and Vasa (red) were used. The long cell extentions seen in the control cyst cell (arrows in I) are missing in the Lam-RNAi cyst cell (arrows in J). Scale bars, 20μm.

K. Cartoon illustration of the role of lamin-B in regulating the CySCs localization and the morphogenesis of cyst cells. See also Figure S2.

Previous studies have shown that increasing the contact between the CySCs and the hub can lead to the displacement of GSCs from the hub (Issigonis et al., 2009; Leatherman and Dinardo, 2010). We found that both Lam-null and tj-driven Lam RNAi male gonads have a reduction of the number of GSCs contacting the hub compared to controls (Figure 3B–D and 3F). Therefore, lamin-B is needed in CySCs to regulate the organization of the niche so that both the CySCs and GSCs can assume proper interactions with the hub.

Lamin-B is required for the morphogenesis of the differentiating cyst cells

The above findings suggest that the CySCs may not undergo proper differentiation to form cyst cells. We analyzed the early differentiating cyst cells in detail and found whereas the TJ+ cyst cells enclosed the germline in developing wild-type L3 male gonads as expected, cyst cells in Lam-null gonads were displaced away from germ cells with many cyst cells mis-localized to the surface of the developing gonads (Figure 3G, 3H, and S2). Using the Flp-out RNAi strategy to specifically mark individual LAM-depleted cyst cells by GFP, we found while the control cyst cells extended their cell bodies to surround the germline cyst, the cell bodies of LAM-depleted cyst cells remained compacted (Figure 3I and 3J). Thus, LAM is required in both the CySCs and their differentiating cyst cells to ensure proper interactions of the GSCs and the TA germline cells with their respective niches (Figure 3K).

Lamin-B regulates nuclear EGFR signaling in CySCs and cyst cells

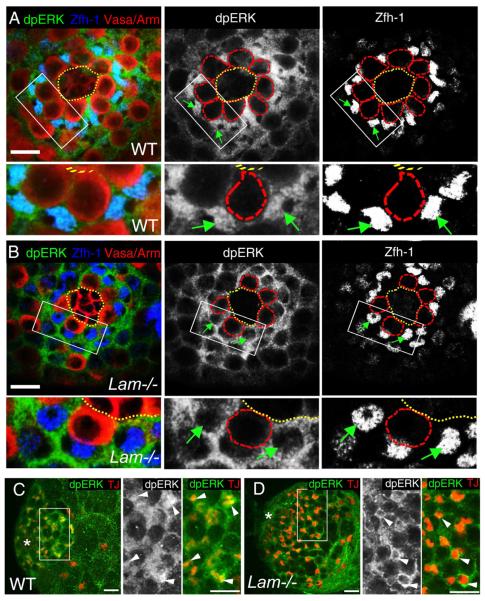

The testis phenotypes observed in Lam-null flies are reminiscent of those seen in cyst cells defective in the EGFR signaling pathway (Kiger et al., 2000; Sarkar et al., 2007; Schulz et al., 2002; Tran et al., 2000). EGFR signals both in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Whether it is the nuclear or cytoplasmic EGFR signaling that is required in cyst cells has remained unknown (Gabay et al., 1997; Kumar et al., 1998; Lesokhin et al., 1999). Our observation suggests that lamin-B could promote the nuclear EGFR signaling in both CySCs and the differentiating cyst cells. We found that overexpression of Lam cDNA in EGFR pathway mutants failed to rescue testis defects (data not shown). Since the nuclear translocation of phosphorylated ERK (dpERK) is important for the nuclear EGFR signaling, we analyzed dpERK localization in CySCs and cyst cells. We found that in wild-type L3 male gonads dpERK was localized in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of almost all of the CySCs and early cyst cells (Figure 4A and 4C). By contrast, dpERK remained largely in the cytoplasm in most of the CySCs (Figure 4B) and early cyst cells in Lam-null gonads (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. LAM regulates dpERK nuclear location in CySCs and cyst cells.

A and B. dpERK is localized in both the cytoplasm and the nuclei of CySCs (blue, Zfh-1) in wild type (A) but is depleted in the nuclei of CySCs in Lam-null (B) L3 male gonads. The boxed areas in (A) and (B) are enlarged at the bottom. Green arrows indicate the CySCs with (A) or without (B) nuclear dpERK staining. Immunostaining using antibodies against dpERK (green), Arm (red, labels the hub), Vasa (red), and Zfh-1 (blue) in wild type (A) and LAM-null (B) L3 male gonads. Hub areas are outlined with yellow dotted lines, while GSCs in the black and white images are outlined with red dotted lines. Scale bars, 10μm.

C and D. dpERK is enriched in the cyst cell nuclei (red, TJ) in wild type (C), but not in Lam-null (D), L3 male gonads. The boxed areas in (C) and (D) are enlarged to the right. Arrowheads, cyst cells with (C) or without (D) nuclear dpERK staining. Asterisks, hubs. Scale bars, 20μm.

See also Figure S3.

Since EGFR signaling is also required in the follicle cells for oogenesis in female flies (Nilson and Schupbach, 1999; Zhao et al., 2000), we analyzed whether lamin-B is required for dpERK nuclear translocation in these cells. We used FLP/FRT-mediated mitotic recombination to generate LamD395 mutant follicle cell clones. The recombination leading to Lam-deletion also removes GFP that marks the wild-type follicle cell nuclei. Thus the follicle cells not marked by GFP are null for lamin-B. We found that dpERK was only localized in the GFP positive nuclei of the Lam wild-type follicle cells (Figure S3). Therefore, LAM is also required for the nuclear localization of dpERK in these cells. Consistent with this, depletion of lamin-B in follicle cells resulted in female sterility (data not shown). Taken together, lamin-B is required for the nuclear EGFR signaling in CySC, cyst cells, and follicle cells that rely on this pathway.

Lamin-B-mediated nuclear ERK localization in CySC is required for proper cell-cell interactions

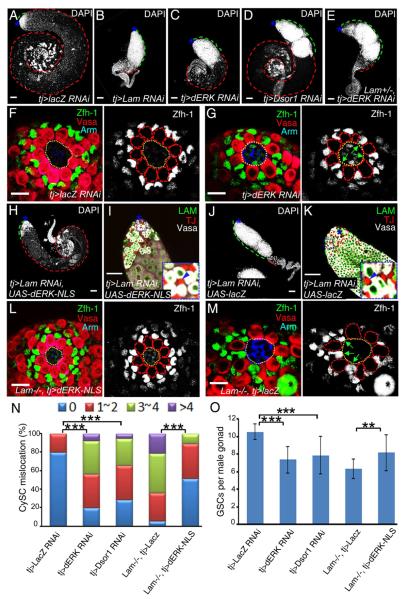

To confirm that lamin-B indeed regulates the CySC lineage through ERK, we depleted either Drosophila ERK (dERK) or Dosophila MAPKK (DSOR1) in the CySC lineage using tj-driven RNAi. Similar to LAM, dERK and DSOR1 function in the CySC lineage to promote the differentiation of the germline (Figure 5A–D). Additionally, a stronger defect in germline differentiation was observed upon dERK depletion in cyst cells lacking one wild-type copy of Lam than those with two copies (compare Figure 5E to 5C). These suggest that LAM promotes EGFR signaling in the CySC lineage by regulating nuclear translocation/retention of dpERK and subsequent pathway activation in the nucleus during spermatogenesis.

Figure 5. LAM regulates GSCs maintenance and differentiation in the CySC lineage through EGFR signaling.

A–E. The CySC lineage depletion of dERK (C) or DSOR1 (D) by tj-driven RNAi phenocopied the CySC lineage depletion of LAM (B) as revealed by the accumulation of DAPI-bright early germ cells compared to control LacZ RNAi (A). Cyst cell depletion of dERK in Lam+/− (E) resulted in a more severe phenotype than in Lam+/+ flies (compare E to C). Green and red dashed lines outline the DAPI-bright early and DAPI-dim late germ cells, respectively. Scale bars, 50μm.

F and G. The CySC lineage depletion of dERK by tj-driven dERK RNAi (G), but not the control lacZ RNAi (F), phenocopied the CySCs mislocalization observed in Lam-null gonads. Arm (blue), Vasa (red), and Zfh-1 (green) label the hub, the germline lineage, and the CySC lineage, respectively. Green arrows in the black and white image in G point to the Zfh-1-expressing CySCs with their nuclei close to the hub. The hubs are outlined with yellow dotted lines, while GSCs (in the black and white images) are outlined with red dotted lines. Scale bars, 10μm.

H–K. The effects of forced expression of dERK-NLS in the CySC lineage depleted of LAM on spermatogenesis. An example of a strongly rescued testis is shown in H and I (19 out of 42) along with the control LacZ rescued testis (J and K). The testis tips in H and J are enlarged in I and K, respectively, with the enlarged insets showing the expression of LAM (green) in germ cells (Vasa+, white) but not in cyst cells (blue arrowheads pointing to the TJ+, red cyst cells). Asterisks, hubs. Scale bars, 50μm.

L and M. Forced expression of dERK-NLS (L), but not LacZ (M), in the CySC lineage, effectively rescued the CySC mislocalization defect in Lam-null L3 male gonads. Hubs, germline cells, CySCs are labeled by Arm (blue), Vasa (red), and Zfh-1 (green), respectively. Green arrows in the black and white image in M point to the Zfh-1+ CySCs with their nuclei next to the hub. The hubs are outlined with yellow dotted lines, while GSCs (in the black and white images) are outlined with red dotted lines. Scale bar, 10μm.

N. Quantification of the percentages of L3 male gonads with mis-localized CySCs as judged by the close proximity of the Zfh-1+ nuclei to the hub. The colored bars indicate the number of CySCs showing mis-localization in each hub. The tj-driven dERK (n=35) or Dsor1 RNAi (n=32) caused a significant increase of gonads with mis-localized CySCs compared to the control tj-driven LacZ RNAi (n=30). The tj-driven expression of dERK-NLS in Lam-null gonads (n=25) resulted in a significant rescue of CySC localization defects compared to control tj-driven LacZ expression (n=26). ***, p<0.001, Wilcoxon Two Sample Test.

O. Quantification of the number of GSCs associated with the hub. The tj-driven dERK (n=21) or Dsor1 RNAi (n=19) caused a significant decrease in the number of GSCs associated with the hub compared to the control tj-driven LacZ RNAi (n=16). The tj-driven expression of dERK-NLS in Lam-null animals (n=15) resulted in a significant increase in the number of GSCs associated with the hub compared to the control tj-driven LacZ expression (n=14). **, p<0.01, ***, p<0.001, Student T tests. Error bars, SD.

See also Figure S4.

Next, we analyzed whether depleting dERK and DSOR1 using tj-driven RNAi would disrupt the interactions of CySCs and GSCs with the hub as seen in the Lam-null gonads. Compared to the control RNAi (tj-driven LacZ RNAi), depletion of either dERK or DSOR1 in the CySC lineage resulted in increased interactions between the CySC and the hub and a corresponding decrease in the number of GSCs contacting the hub (Figure 5F, 5G, 5N, 5O, and S4A), similar to those seen in the Lam-null or Lam-RNAi gonads (Figure 3B–F). Again the overall numbers of the CySC lineage cells (judged by Zfh-1 staining) per gonads were similar (p>0.05) among control tj-driven LacZ RNAi (33.1 ±5.3, n=16), dERK RNAi (33.8 ±7.2, n=17), and Dsor1 RNAi (34.6 ±6.5, n=17).

To directly test the role of LAM in the nuclear translocation of dpERK in the CySC lineage, we linked a nuclear localization signal (NLS) in frame to the C-terminus of dERK and used the tj promoter to express it in the CySC lineage depleted of LAM by RNAi. We found that this partially rescued the GSC differentiation defect as revealed by the formation of spermatocytes and sperm bundles (Figure 5H–K) in 45.2% of testes (n=42). Although the remaining testes still had a large number of early germ cells (Figure S4B and S4C), they are less compared to LAM depleted testes rescued with LacZ controls (compare Figure S4B and S4C to 5J and 5K). Despite the formation of sperm bundles, forced expression of dERK-NLS failed to rescue fertility (data not shown). Additionally, we observed a strong rescue in 40.6% of the Lam-null L3 male gonads (n=32) by expressing dERK-NLS in the CySC lineage. These rescued gonads formed spermatocytes and did not accumulate many early germline cells (compare Figure S4E&S4E' to S4F&S4F'). Although the remaining L3 male gonads still accumulated early germ cells (Figure S4G&S4G'), the degree of accumulation was less compared to Lam-null gonads (compare Figure S4G&S4G' to S4E&S4E'). The size of all of the rescued gonads appeared smaller than wild type gonads, but they all contained spermatocytes. Thus the block of spermatogonia to spermatocyte transition due to lamin-B depletion can be rescued by forced expression of nuclear ERK in the CySC lineage. Importantly, forced expression of dERK in the CySC nuclei resulted in a significant reversal of the interaction defects between CySCs and GSCs with the hub, which corresponded to the increased number of GSCs contacting the hub as compared to the Lam-null gonads (Figure 5L–O). Our findings demonstrate that LAM promotes GSC-hub interaction and GSC differentiation at least in part by facilitating dERK nuclear localization in the CySC lineage.

Previous studies show that the adhesion between the CySC and the hub is mediated by both E-cadherin and integrin beta (Issigonis et al., 2009; Voog et al., 2008). We analyzed whether lamin-B is required in the CySCs to prevent excess expression of E-cadherin and integrin beta. E-cadherin expression was similar in the wild type and Lam-null L3 male gonads (Figure S4H and S4I). The expression of integrin beta (βPS) in CySCs was, however, increased in Lam-null gonads compared to controls (Figure S4J and S4K). Thus the lamin-B-regulated EGFR signaling could limit the integrin beta-mediated CySC and hub interactions.

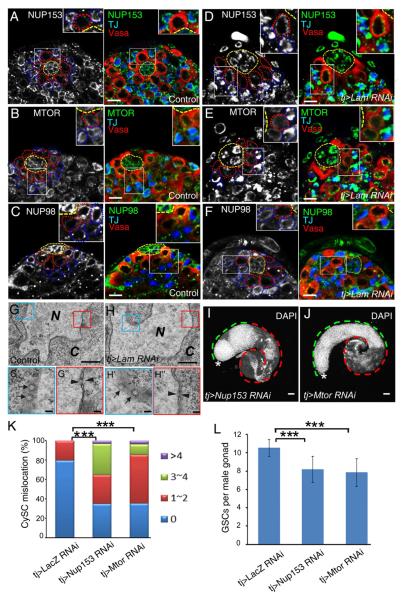

Lamin-B regulates nuclear EGFR signaling through nucleoporins

In mammalian tissue culture cells, the nuclear translocation and retention of phosphorylated ERK require nucleoporins (NUP) 153 and TPR, which are known to bind to one another (Adachi et al., 1999; Lorenzen et al., 2001; Matsubayashi et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2010; Vomastek et al., 2008; Whitehurst et al., 2002). Additionally, in vitro studies suggest that lamins bind and regulate NUP153 localization in the nuclear pore complex (NPC). The physiological significance of these observations is however unknown in any in vivo settings. We reasoned that LAM might regulate dpERK through NUP153 and TPR in both CySCs and cyst cells. Consistent with this, we found that Drosophila NUP153 interacts with LAM (Figure 5SA). In wild-type testes, NUP153, MTOR (the Drosophila TPR), and NUP98 exhibited even distributions around the nuclear rim in the GSCs, TA germline cells, CySCs, and cyst cells (Figure 6A–C and S5B–E). LAM depletion in the CySC lineage caused aggregation of NUP153 and MTOR without affecting the distribution of NUP98 in these cells (Figure 6D–F and S5F–H). Additionally, we analyzed the Lam-null mitotic follicle cell clones in female ovaries and found that LAM was also required for proper localization of NUP153 and MTOR, but not NUP98 and NUP154 (Figure S5I–L).

Figure 6. LAM regulates EGFR signaling through NUP153 and MTOR.

A–F. NUP153 (A), MTOR (B), and NUP98 (C) are evenly distributed throughtout the nuclear envelope of both CySCs (TJ, red) and GSCs in adult testes treated with control RNAi (tj-Gal4>lacZ RNAi), whereas LAM depletion in CySCs (tj-Gal4>Lam RNAi) caused aggregation of NUP153 (D) and MTOR (E) without affecting NUP98 (F) in CySCs. Insets, enlarged images revealing in more detail the distribution of nucleoporins in CySCs. The bright dots in (C) and (F) are non-specific antibody labels. The hubs, GSCs, and CySCs are outlined with yellow, red, or blue dotted lines, respectively. Scale bars, 10μm.

G and H. Electron micrographs of cyst cells revealing that LAM depletion did not affect the assembly of nucleopores in these cells. Both the face (G' and H', arrows) and side (G” and H”, arrowheads) views of nucleopores are shown. N, nucleus; C, cytoplasm. Scale bars, 0.1μm.

I and J. Depletion of either NUP153 (I) or MTOR (J) in the CySC lineage resulted in the accumulation of DAPI-bright early germ cells (green dashed lines) at the expense of DAPI-dim differentiated germ cells (red dashed lines) in testes, similar to those seen in LAM depletion. Asterisks, hubs. Scale bars, 50μm.

K. Quantification of the percentages of L3 gonads with mis-localized CySCs as judged by the close proximity of the Zfh-1+ nuclei to the hub. The colored bars show the number of CySCs near each hub. The tj-driven Nup153 (n=32) or Mtor RNAi (n=28) caused a significant increase of gonads with mis-localized CySCs compared to the control tj-driven LacZ RNAi (n=25). ***, p<0.001, Wilcoxon Two Sample Test.

L. Quantification of the number of GSCs associated with the hub. The tj-driven Nup153 (n=17) or Mtor RNAi (n=21) caused a significant decrease in the number of GSCs associated with the hub compared to the control tj-driven LacZ RNAi (n=13). ***, p<0.001, Student T tests. Error bars, SD.

See also Figure S5.

Consistent with the normal import of nuclear proteins such as TJ and NLS-GFP in the LAM-depleted CySC lineage (not shown), electron microscopy analyses revealed that NPCs in these cells were indistinguishable between Lam-depleted and control testes (Figure 6G and 6H). Therefore instead of regulating the general NPC structure and function, LAM is specifically required for dpERK nuclear translocation and/or retention by ensuring proper NPC localization of NUP153 and MTOR in the CySC lineage. Supporting a role of NUP153 and MTOR in EGFR signaling in these cells, depletion of either protein in these cells caused a similar defect in germline differentiation as seen in Lam mutants (Figure 6I and 6J, compare to 5B). Importantly, we found that the CySCs depleted of either NUP153 or MTOR exhibited an increased interaction with the hub, which corresponded to a decrease of the number of the hub-associated GSCs (Fig. 6K and 6L), but the number of CySCs was not affected (data not show). Thus lamin-B regulates EGFR signaling in the CySC lineage by controlling the proper distribution of NUP153 and MTOR in the NPCs.

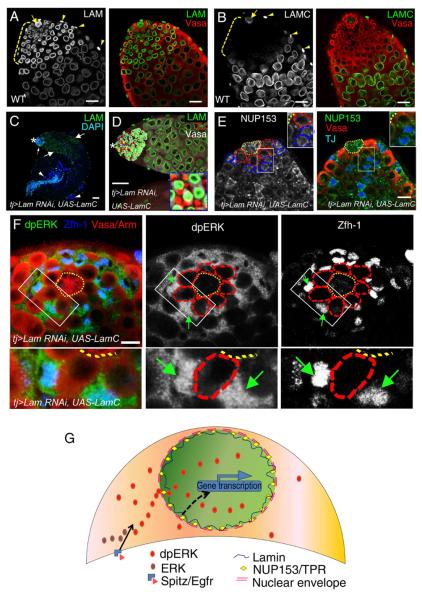

A- and B-type lamins have shared functions

Since a given animal cell often expresses both A- and B-types of lamins, a critical question in the field is whether the kinds of lamins can compensate one another for certain functions in vivo. This is particularly relevant with regard to the role of lamins in regulating NUP153 because both A- and B-type lamins can bind to this nucleoporin (Al-Haboubi et al., 2011; Smythe et al., 2000). Immunofluorescence analyses show that while LAM is express in all cell types in the testes (Figure 7A and S6A), LAMC is only expressed in the hub cells and late stage germline and cyst cells, but is undetectable in the early stage germ cells (including GSCs, gonialblasts, and spermatogonia), the surrounding CySCs, and early cyst cells (Figure 7B and S6B). Similarly, whereas LAM is expressed in the follicle cells in the early stage ovaries, LAMC is undetectable in these cells (Figure S6C and S6D). The differential expression of lamins coupled with the strong defects observed in cells only expressing LAM offer us a unique opportunity to test whether LAM and LAMC have shared functions.

Figure 7. A shared function between A- and B-type lamins in the CySC lineage.

A and B. A strong and ubiquitous expression of LAM (A) in the wild-type adult testis compared to the undetectable LAMC in the CySCs, early cyst cells, and early germ cells (B) in the tip region (brackets). LAMC is expressed in the hub and basement muscle cells. Arrows, hub cells. Arrowheads, basement muscle cells. Scale bars, 20μm.

C and D. Ectopic expression of tj>LamC cDNA in cyst cells resulted in strong (34 out of 56) or weak (22 out of 56) rescues of germ cell differentiation defects caused by the CySC lineage-specific Lam-RNAi as judged by LAM (green) and DAPI (blue) staining. Small arrows, large arrows, and arrowheads in (C) indicate early germ cells, spermatocytes, and sperm bundles, respectively, in a strongly rescued testis. The tip region in (C) is enlarged in (D) with the inset showing cyst cells (red, lacking LAM) and germ cells (white, containing LAM). An example of a weak LAMC rescued testis and a control tj-driven LacZ cDNA expressed testis are shown in Figure S6E&F and S6G&H, respectively. Asterisks, hubs. Scale bar, 50μm.

E. Ectopic expression of tj>LamC cDNA in the CySC lineage resulted in a partial rescue of the NUP153 localization defect caused by tj>Lam-RNAi in a strongly rescued testis. An example of a testis with control tj-driven LacZ cDNA expression is shown in Figure S6I. The hubs, GSCs, and CySCs are outlined with yellow, red, or blue dotted lines, respectively. Scale bars, 10μm.

F. The nuclear dpERK localization defect caused by the CySC lineage specific Lam-RNAi was partially rescued by the ectopic expression of tj-driven LamC cDNA in a strongly rescued L3 male gonads. Boxed areas in (F) are enlarged to the bottom. Green arrows point to CySCs with nuclear dpERK staining. Images of the control expression of tj-driven LacZ cDNA are shown in Figure S6J. Arm (red), Vasa (red), and Zfh-1 (blue) label the hub, the germline lineage, and the CySC lineage respectively. The hub and GSCs are outlined with yellow and red dotted lines, respectively. Scale bar, 10μm.

G. A model illustrating that LAM regulates the maintenance and differentiation of the GSC and transit-amplifying germ cells by controlling the localization of CySCs and cyst cell morphogenesis via the nucleoporin-dependent EGFR signaling.

See also Figure S6.

We found that ectopic expression of LAMC cDNA using tj-Gal4 in the CySC lineage partially rescued the germ cell differentiation defects in 58.9% of LAM depleted testes (Figure 7C and 7D, compare to Figure S6G and S6H). These rescued testes were shorter (~1.4 mm) compared to controls (~2.0 mm), but they contained germ cells at all stages of differentiation. Although the remaining 41.1% testes appeared much shorter (~0.8 mm) and abnormal, they had less severe accumulation of early germ cells compared to controls, suggesting a weak rescue (Figure S6E and S6F). As expected, LAMC expression also partially rescued the NUP153 location defects (Figure 7E, compare to Figure S6I), which corresponded to a partial rescue of nuclear dpERK localization in the CySCs depleted of LAM (Figure 7F, compare to Figure S6J). Therefore A- and B-type lamins have a shared function in nuclear EGFR signaling by ensuring proper NUP153 localization.

Discussion

The difficulty to understand the role of lamins in the context of development and disease has been confounded by the diverse functions ascribed to these proteins based on in vitro studies. Recent efforts in using animal models and ES cells have shown that B-type lamins are required for proper building of at least certain organs (Kim et al., 2012), although how lamins regulate organogenesis is unknown. The lamin-regulated EGFR signaling in CySCs and cyst cells we uncover here (Figure 7G) represents the first molecular mechanism for these proteins in promoting development.

It has been known for some time that lamins are required for the even distribution of nuclear pores in the nuclear envelope in tissue culture cells in vitro. The physiological significance of such a function has however remained unknown. Also unclear is the in vivo relevance of Nup153-regulated nuclear translocation/retention of phosphorylated ERK. Our findings demonstrate that lamin-regulated Nup153 distribution is critical for proper nuclear retention of dpERK in the CySC lineage and follicle cells, which are two somatic cell types that we find to exhibit strong nuclear dpERK staining in male and female reproductive systems, respectively. Interestingly, similar to the effect of lamin-B depletion in the CySC lineage in males, the follicle cells depleted of lamin-B also leads to oogenesis defects and female sterility (data not shown). Therefore, our findings strongly suggest that lamin is required in the niche or microenvironment to support germline development in both sexes. It will be important to further study whether lamins have a general role in regulating cells in the niche that requires nuclear EGFR signaling and whether such function could contribute toward diseases caused by lamin mutations in humans.

We have shown that lamins and nucleoporin-regulated EGFR signaling in the nuclei of CySCs is important to limit the interaction between the CySCs with the hub cells. Depletion of lamin-B, NUP153, MTOR, ERK, or MAPKK all leads to increased CySC-hub interactions and a corresponding decrease of hub-associated GSCs. Importantly, this defect can be rescued by forced nuclear expression of ERK in CySCs depleted of lamin-B. CySCs depleted of lamin-B exhibited stronger expression of integrin beta than that of the wild-type CySCs. Previous studies have shown that the expression of SOCS36E, the JAK/STAT induced inhibitor that suppresses JAK/STAT pathway, inhibits the expression of integrin beta in CySCs (Issigonis et al., 2009). Since EGFR signaling can activate SOCS36E in certain cell types in Drosophila (Herranz et al., 2012), we speculate that the lamin-B-regulated EGFR signaling might control the integrin beta-mediated interaction between CySCs and the hub via the SOCS36E regulatory network. Further studies aimed at understanding how Lamin-B and nucleoporin-regulated EGFR signaling controls integrin expression in CySC cells should shed light on the role of the nuclear lamina in coordinating different signaling pathways during spermatogenesis.

Since the discovery of human diseases caused by mutations in the A-type lamins, much effort has been devoted to decipher the disease mechanism by focusing the study on A-type lamins. Mice deleted of the gene encoding for A-type lamins die a few weeks after birth (Sullivan et al., 1999), whereas deleting either one or both genes encoding for lamin-B1 or –B2 results in perinatal lethality (Coffinier et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2011; Vergnes et al., 2004). These observations have led to the prevailing but unproven belief that A- and B-type lamins have very distinct functions. Our findings demonstrate that A- and B-type have shared functions in the CySC lineage. This shared function could explain why the loss of B-type lamin results in strong defects in cyst and follicle cells that only express lamin-B. Therefore, our findings emphasize the need to consider the shared functions of A- and B-type lamins when interpreting the developmental or disease phenotypes caused by mutations in a specific lamin.

As an important node that connects chromatin in the nucleus to cytoskeleton in the cytoplasm, lamins may have a general role in integrating signaling pathways with gene regulation and cell morphogenesis in somatic cells that form the niche for stem or progenitor cells. Considering the broad roles of signaling pathways, the function of lamins in cell signaling we report here could help to explain the diverse roles assigned to these nuclear proteins by previous in vitro studies (Dechat et al., 2008). We suggest that the function of lamins in a given cell type could differ depending on the signaling pathways used by the cell. Therefore, to reach a comprehensive understand of lamins, it is important to use tissue specific deletion strategies. The effort to understand the role of lamins in different stem cell niches should also contribute toward the study of the disease mechanism of nuclear lamina-based tissue degeneration.

Experimental Procedures

All mutant and transgenic Drosophila strains used in this study were described in detail in the Supplementary Materials and Methods. Different strains were raised at low density on standard cornmeal/molasses/agar fly food at 25°C unless stated otherwise. To rescue LAM depletion, we created UAS-dERK-NLS transgenic fly strains. FLP/FRT-mediated mitotic recombination (Xu and Rubin, 1993) was used to generate Lam-null mutant germline clones using the LamD395 allele. To analyze the effect of LAM deletion on cyst cell morphology, we used the FRT `flip out' method (Pignoni and Zipursky, 1997). Testes containing LAM-depleted cyst cells were dissected and processed for immunostaining 4–5 days after heat-shocked for 1 hour at 37°C at the 8-day pupal stage. GFP expression allowed the marking of the morphology of individual cyst cells. For more detail procedures of clonal analyses and RNAi-FRT `flip out' strategy please refer to the Supplementary Materials and Methods. All other techniques used, including immunofluorescence/electron microscopy, nuclear extract preparation, and immunoprecipitation are also detailed in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Highlights

LAM functions in the cyst stem cell (CySC) lineage to regulate the germline.

LAM regulates CySC in the niche and in cyst cell morphogenesis.

LAM ensures nuclear EGFR signaling via specific nucleoporins in the CySC lineage.

A- and B-type lamins have shared functions in the CySC lineage.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Allan Spradling and members of his group for valuable support, Drs, Mark Van Doren, Mitchell Dushay, Lori Wallrath, Kristen Johansen, Erica Selva, Silvia Gigliotti, and Ruth Lehmann for fly strains and antibodies, Matthew Sieber, Alexis Marianes, William Yarosh, and members of the Zheng lab for critical comments. Supported by R01 GM056312 (Y.Z.) and R01 HD065816 (X.C.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental Information

The supplementary materials contain detailed experimental procedures, Drosophila strains, 6 supplemental figures and 2 supplemental tables.

References

- Adachi M, Fukuda M, Nishida E. Two co-existing mechanisms for nuclear import of MAP kinase: passive diffusion of a monomer and active transport of a dimer. EMBO J. 1999;18:5347–5358. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Haboubi T, Shumaker DK, Koser J, Wehnert M, Fahrenkrog B. Distinct association of the nuclear pore protein Nup153 with A- and B-type lamins. Nucleus. 2011;2:500–509. doi: 10.4161/nucl.2.5.17913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank EM, Gruenbaum Y. The nuclear lamina and heterochromatin: a complex relationship. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:1705–1709. doi: 10.1042/BST20110603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry CM, Matunis EL. Epigenetic regulation of stem cell maintenance in the Drosophila testis via the nucleosome-remodeling factor NURF. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:557–567. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffinier C, Chang SY, Nobumori C, Tu Y, Farber EA, Toth JI, Fong LG, Young SG. Abnormal development of the cerebral cortex and cerebellum in the setting of lamin B2 deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5076–5081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908790107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffinier C, Jung HJ, Nobumori C, Chang S, Tu Y, Barnes RH, 2nd, Yoshinaga Y, de Jong PJ, Vergnes L, Reue K, et al. Deficiencies in lamin B1 and lamin B2 cause neurodevelopmental defects and distinct nuclear shape abnormalities in neurons. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:4683–4693. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-06-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies EL, Fuller MT. Regulation of self-renewal and differentiation in adult stem cell lineages: lessons from the Drosophila male germ line. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:137–145. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cuevas M, Matunis EL. The stem cell niche: lessons from the Drosophila testis. Development. 2011;138:2861–2869. doi: 10.1242/dev.056242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechat T, Pfleghaar K, Sengupta K, Shimi T, Shumaker DK, Solimando L, Goldman RD. Nuclear lamins: major factors in the structural organization and function of the nucleus and chromatin. Genes Dev. 2008;22:832–853. doi: 10.1101/gad.1652708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlan LE, Sproul D, Thomson I, Boyle S, Kerr E, Perry P, Ylstra B, Chubb JR, Bickmore WA. Recruitment to the nuclear periphery can alter expression of genes in human cells. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller MT, Spradling AC. Male and female Drosophila germline stem cells: two versions of immortality. Science. 2007;316:402–404. doi: 10.1126/science.1140861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay L, Seger R, Shilo BZ. MAP kinase in situ activation atlas during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 1997;124:3535–3541. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonczy P, DiNardo S. The germ line regulates somatic cyst cell proliferation and fate during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Development. 1996;122:2437–2447. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.8.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman B, Channels W, Qiu M, Iglesias P, Yang G, Zheng Y. Lamin B counteracts the kinesin Eg5 to restrain spindle pole separation during spindle assembly. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:35238–35244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.140749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guelen L, Pagie L, Brasset E, Meuleman W, Faza MB, Talhout W, Eussen BH, de Klein A, Wessels L, de Laat W, et al. Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature. 2008;453:948–951. doi: 10.1038/nature06947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy RW, Tokuyasu KT, Lindsley DL, Garavito M. The germinal proliferation center in the testis of Drosophila melanogaster. J Ultrastruct Res. 1979;69:180–190. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(79)90108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz H, Hong X, Hung NT, Voorhoeve PM, Cohen SM. Oncogenic cooperation between SOCS family proteins and EGFR identified using a Drosophila epithelial transformation model. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1602–1611. doi: 10.1101/gad.192021.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hime GR, Brill JA, Fuller MT. Assembly of ring canals in the male germ line from structural components of the contractile ring. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Pt 12):2779–2788. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.12.2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issigonis M, Tulina N, de Cuevas M, Brawley C, Sandler L, Matunis E. JAK-STAT signal inhibition regulates competition in the Drosophila testis stem cell niche. Science. 2009;326:153–156. doi: 10.1126/science.1176817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiger AA, Jones DL, Schulz C, Rogers MB, Fuller MT. Stem cell self-renewal specified by JAK-STAT activation in response to a support cell cue. Science. 2001;294:2542–2545. doi: 10.1126/science.1066707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiger AA, White-Cooper H, Fuller MT. Somatic support cells restrict germline stem cell self-renewal and promote differentiation. Nature. 2000;407:750–754. doi: 10.1038/35037606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, McDole K, Zheng Y. The function of lamins in the context of tissue building and maintenance. Nucleus. 2012;3:256–262. doi: 10.4161/nucl.20392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Sharov AA, McDole K, Cheng M, Hao H, Fan CM, Gaiano N, Ko MS, Zheng Y. Mouse B-type lamins are required for proper organogenesis but not by embryonic stem cells. Science. 2011;334:1706–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1211222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar JP, Tio M, Hsiung F, Akopyan S, Gabay L, Seger R, Shilo BZ, Moses K. Dissecting the roles of the Drosophila EGF receptor in eye development and MAP kinase activation. Development. 1998;125:3875–3885. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.19.3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran RI, Spector DL. A genetic locus targeted to the nuclear periphery in living cells maintains its transcriptional competence. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:51–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherman JL, Dinardo S. Zfh-1 controls somatic stem cell self-renewal in the Drosophila testis and nonautonomously influences germline stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherman JL, Dinardo S. Germline self-renewal requires cyst stem cells and stat regulates niche adhesion in Drosophila testes. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:806–811. doi: 10.1038/ncb2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesokhin AM, Yu SY, Katz J, Baker NE. Several levels of EGF receptor signaling during photoreceptor specification in wild-type, Ellipse, and null mutant Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1999;205:129–144. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MA, Alls JD, Avancini RM, Koo K, Godt D. The large Maf factor Traffic Jam controls gonad morphogenesis in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:994–1000. doi: 10.1038/ncb1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JG, Fuller MT. Somatic cell lineage is required for differentiation and not maintenance of germline stem cells in Drosophila testes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18477–18481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215516109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen JA, Baker SE, Denhez F, Melnick MB, Brower DL, Perkins LA. Nuclear import of activated D-ERK by DIM-7, an importin family member encoded by the gene moleskin. Development. 2001;128:1403–1414. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Tsai MY, Wang S, Lu B, Chen R, Iii JR, Zhu X, Zheng Y. Requirement for Nudel and dynein for assembly of the lamin B spindle matrix. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:247–256. doi: 10.1038/ncb1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi Y, Fukuda M, Nishida E. Evidence for existence of a nuclear pore complex-mediated, cytosol-independent pathway of nuclear translocation of ERK MAP kinase in permeabilized cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41755–41760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Alarcon A, Pavlovic M, Wismar J, Schmitt B, Eriksson M, Kylsten P, Dushay MS. Characterization of lamin mutation phenotypes in Drosophila and comparison to human laminopathies. PLoS One. 2007;2:e532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilson LA, Schupbach T. EGF receptor signaling in Drosophila oogenesis. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1999;44:203–243. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott BB, Hudson A, Brady R, Schulz C. Control of germline stem cell division frequency--a novel, developmentally regulated role for epidermal growth factor signaling. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peric-Hupkes D, Meuleman W, Pagie L, Bruggeman SW, Solovei I, Brugman W, Graf S, Flicek P, Kerkhoven RM, van Lohuizen M, et al. Molecular maps of the reorganization of genome-nuclear lamina interactions during differentiation. Mol Cell. 2010;38:603–613. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignoni F, Zipursky SL. Induction of Drosophila eye development by decapentaplegic. Development. 1997;124:271–278. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KL, Zullo JM, Bertolino E, Singh H. Transcriptional repression mediated by repositioning of genes to the nuclear lamina. Nature. 2008;452:243–247. doi: 10.1038/nature06727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A, Parikh N, Hearn SA, Fuller MT, Tazuke SI, Schulz C. Antagonistic roles of Rac and Rho in organizing the germ cell microenvironment. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1253–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz C, Wood CG, Jones DL, Tazuke SI, Fuller MT. Signaling from germ cells mediated by the rhomboid homolog stet organizes encapsulation by somatic support cells. Development. 2002;129:4523–4534. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon DN, Wilson KL. The nucleoskeleton as a genome-associated dynamic `network of networks'. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:695–708. doi: 10.1038/nrm3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ER, Cai KQ, Smedberg JL, Ribeiro MM, Rula ME, Slater C, Godwin AK, Xu XX. Nuclear entry of activated MAPK is restricted in primary ovarian and mammary epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe C, Jenkins HE, Hutchison CJ. Incorporation of the nuclear pore basket protein nup153 into nuclear pore structures is dependent upon lamina assembly: evidence from cell-free extracts of Xenopus eggs. EMBO J. 2000;19:3918–3931. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan T, Escalante-Alcalde D, Bhatt H, Anver M, Bhat N, Nagashima K, Stewart CL, Burke B. Loss of A-type lamin expression compromises nuclear envelope integrity leading to muscular dystrophy. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:913–920. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarayrah L, Herz HM, Shilatifard A, Chen X. Histone demethylase dUTX antagonizes JAK-STAT signaling to maintain proper gene expression and architecture of the Drosophila testis niche. Development. 2013;140:1014–1023. doi: 10.1242/dev.089433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran J, Brenner TJ, DiNardo S. Somatic control over the germline stem cell lineage during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Nature. 2000;407:754–757. doi: 10.1038/35037613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MY, Wang S, Heidinger JM, Shumaker DK, Adam SA, Goldman RD, Zheng Y. A mitotic lamin B matrix induced by RanGTP required for spindle assembly. Science. 2006;311:1887–1893. doi: 10.1126/science.1122771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulina N, Matunis E. Control of stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila spermatogenesis by JAK-STAT signaling. Science. 2001;294:2546–2549. doi: 10.1126/science.1066700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnes L, Peterfy M, Bergo MO, Young SG, Reue K. Lamin B1 is required for mouse development and nuclear integrity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10428–10433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401424101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vomastek T, Iwanicki MP, Burack WR, Tiwari D, Kumar D, Parsons JT, Weber MJ, Nandicoori VK. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 (ERK2) phosphorylation sites and docking domain on the nuclear pore complex protein Tpr cooperatively regulate ERK2-Tpr interaction. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6954–6966. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00925-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voog J, D'Alterio C, Jones DL. Multipotent somatic stem cells contribute to the stem cell niche in the Drosophila testis. Nature. 2008;454:1132–1136. doi: 10.1038/nature07173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst AW, Wilsbacher JL, You Y, Luby-Phelps K, Moore MS, Cobb MH. ERK2 enters the nucleus by a carrier-independent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7496–7501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112495999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Rubin GM. Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development. 1993;117:1223–1237. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SH, Chang SY, Yin L, Tu Y, Hu Y, Yoshinaga Y, de Jong PJ, Fong LG, Young SG. An absence of both lamin B1 and lamin B2 in keratinocytes has no effect on cell proliferation or the development of skin and hair. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3537–3544. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D, Clyde D, Bownes M. Expression of fringe is down regulated by Gurken/Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor signalling and is required for the morphogenesis of ovarian follicle cells. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 21):3781–3794. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.21.3781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y. A membranous spindle matrix orchestrates cell division. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:529–535. doi: 10.1038/nrm2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoller R, Schulz C. The Drosophila cyst stem cell lineage: Partners behind the scenes? Spermatogenesis. 2012;2:145–157. doi: 10.4161/spmg.21380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.