Abstract

Bone marrow (BM) microenvironment, which is regulated by hypoxia and proteolytic enzymes, is crucial for stem/progenitor cell function and mobilization involved in postnatal neovascularization. We demonstrated that NADPH oxidase2 (Nox2)-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) are involved in post-ischemic mobilization of BM cells and revascularization. However, role of Nox2 in regulating BM microenvironment in response to ischemic injury remains unknown. Here we show that hindlimb ischemia of mice increases ROS production in both the endosteal and central region of BM tissue in situ, which is almost completely abolished in Nox2 knockout (KO) mice. This Nox2-dependent ROS production is mainly derived from Gr-1+ myeloid cells in BM. In vivo injection of hypoxyprobe reveals that endosteum at the BM is hypoxic with high expression of HIF-1α in basal state. Following hindlimb ischemia, hypoxic areas and HIF-1α expression are expanded throughout the BM, which is inhibited in Nox2 KO mice. This ischemia-induced alteration of Nox2-dependent BM microenvironment is associated with an increase in VEGF expression and Akt phosphorylation in BM tissue, thereby promoting Lin− progenitor cell survival and expansion, leading to their mobilization from BM. Furthermore, hindlimb ischemia increases proteolytic enzymes MT1-MMP expression and MMP-9 activity in BM, which is inhibited in Nox2 KO mice. In summary, Nox2-dependent increase in ROS play a critical role in regulating hypoxia expansion and proteolytic activities in BM microenvironment in response to tissue ischemia. This in turn promotes progenitor cell expansion and reparative mobilization from BM, leading to post-ischemic neovascularization and tissue repair.

Keywords: Hematopoietic stem cell, Mobilization, Reactive oxygen species, Ischemia, Hypoxia

Introduction

Bone marrow (BM)-derived stem and progenitor cells have a critical role in maintaining vascular health and facilitating vasculogenesis/angiogenesis [1]. The BM microenvironment, also termed the stem cell niche, provides essential cues that regulate stem and progenitor cell functions and their mobilization into the circulation involved in postnatal neovascularization [2]. Hypoxia and proteolytic enzymes are key extrinsic factors that affect BM microenvironment regulating stem and progenitor cell function and their reparative mobilization. Stem/progenitor cells are originally shown to be located in two different BM microenvironments, including the BM interface (endosteal niche) which provides low oxygen environment for maintaining hematopoietic stem cells quiescence, and the vascular niche which provides oxygenated environment for cell proliferation and differentiation [3–5]. Ischemic injury increases cytokines and growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in BM and circulation, which in turn activates matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 and releases soluble Kit ligand in the BM [6]. MMPs including MMP-9, which is secreted mainly by neutrophils in BM [7], and MT (membrane type)1-MMP [8], which is anchored on the cell surface, plays a significant role in stem/progenitor cell mobilization and angiogenesis. Thus, understanding mechanisms by which ischemic injury regulates BM microenvironment and stem/progenitor cell function is essential for developing novel therapeutic strategies for treatment of various ischemic diseases.

Although excess amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anion (O2•−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are detrimental to cells, ROS at appropriate level function as signaling molecules to mediate normal cell growth, migration, differentiation, apoptosis and senescence [9]. Evidence suggests that redox status and ROS affect stem/progenitor cell function including cell survival and proliferation [10–13] as well as interaction between stem cells and their niches [14]. Self-renewal and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells are regulated by intracellular ROS and niche microenvironment [15]. One of the major sources of ROS involved in signaling is NADPH oxidase (Nox) which is expressed in phagocytes and non-phagocytic cells [9]. Differentiated myeloid cells such as neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages generate a large amount of O2•−extracellularly via activation of Nox2 (also known as gp91phox). Nox isoforms are also expressed in stem/progenitor cells [16] and Nox-derived ROS are involved in differentiation, proliferation, senescence or apoptosis [12, 17, 18]. We previously demonstrated that hindlimb ischemia increases Nox2-dependent ROS production in isolated BM-derived mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) and that post-ischemic neovascularization and BM cells (BMCs) mobilization are impaired in Nox2−/− mice [19]. However, the mechanisms by which Nox2 regulates progenitor cell function and mobilization, and a role of Nox2 in BM microenvironment remain unknown.

In this study using hindlimb ischemia model of Nox2−/− mice and in vivo injection of O2− reactive dye, we provide the direct evidence that ROS production is markedly increased in entire BM, in a Nox2-dependent manner, following ischemic injury in vivo. We also show that Nox2-derived ROS play an important role in hindlimb ischemia-induced expansion of hypoxia, HIF1α/VEGF expression as well as Akt and proteolytic enzyme (MT1-MMP and MMP-9) activation in BM in situ. Furthermore, these ROS-mediated, hypoxic BM microenvironment alternations induced by ischemic injury regulate progenitor cell survival and expansion, thereby promoting their mobilization from BM. Our study will provide new insights into role of Nox in redox regulation of BM microenvironment during postnatal neovascularization and tissue repair in response to injury.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement for Animal Study

Study protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Institutional Biosafety Committee of University of Illinois at Chicago (A09–066), and the experiments were performed according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health.

Mouse Hindlimb Ischemia Model

Nox2−/− mice and their age- (range 8–12 week-old) and sex-matched wild-type (WT) mice (C57BL/6J) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine), and were fed regular chow and water containing antibiotics, such as sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim (Hi-Tech Pharmacal, Amityville, NY) under specific pathogen-free conditions at university of Illinois at Chicago. Mice were subjected to unilateral hindlimb surgery under anesthesia with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). To induce hindlimb ischemia, left femoral arteries were ligated and removed from the branch point for profunda femoris to the proximal portion of the saphenous artery. All arterial branches between the ligations were obliterated using an electrical coagulator. Mice with major bleeding or signs of infections during observation were euthanized. To examine the BM, we used only long bones of contra-lateral legs that is not subjected to hindlimb surgery to exclude the direct effect of ischemia in the BM. Samples were collected immediately after euthanasia.

O2•− Detection in Mice

Dihydroethidium (DHE) (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) was prepared as a 1 mg/ml solution in 1% Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and administered at 10 mg per kg of body weight by intravenous injection. Mice were killed and immediately perfusion-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde 1 hour after DHE injections. Frozen sections of the BM were prepared by the direct flushing of BM cavities with O.C.T. compound that allowed it to keep the structure of BM central regions, and were observed by confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with excitation at 510–550 nm and emission >585 nm to detect oxidized ethidium. In some experiments, frozen sections were stained with rat-origin anti-CD45 or anti-Gr-1 (RB6-8C5) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), and with DyLight 488 conjugated anti-rat IgG angibodies (Jackson ImmnoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). To quantify fluorescence on captured images, a parallelogram with size approximate 50 × 500 µm was drawn from the endosteum into the BM and defined as the endosteal region. The same size of parallelogram was drawn in the middle of BM as the central region. The mean fluorescence intensity of the regions and background signals in the area with no cell were measured on ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). The fluorescent signal was calculated as the mean fluorescence intensity subtracted by the background signals in each sections.

O2•− detection using isoluminol enhanced chemiluminescence assay

O2•− production in isolated Gr1+ cells was measured using isoluminol enhanced chemiluminescent method in 6-mm diameter wells of 96-well, flat-bottom, white tissue culture plates (E&K Scientific, Campbell, CA). Freshly isolated BM Gr-1+ Cells were resuspended in Krebs-HEPES buffer. The buffer with 100 µM isoluminol and 40 U/ml HRP was incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Aliquot (200 µl) of the cells (1×106 cells) was added into the well and assayed for chemiluminescence (CL) at 37°C in a Wallac 1420 Multilabel Counter (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA). The CL counts per second (cps) was continually recorded for 30 min. To isolate Gr-1+ cells from total BM cells, immunomagnetic cell sorting using EasySep (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC) with biotinylated anti-Gr-1 antibodies (RB6-8C5: eBioscience, San Diego, CA). The measurement was started within 1 hour after sacrificing the mice.

Hypoxia Detection by Pimonidazole

Mice were injected 60 mg/kg pimonidazole hydrochloride (Hypoxyprobe) (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) into peritoneal cavity 3 hours prior to tissue harvest. Preparation of paraffin sections of decalcified femurs and immunolabeling of pimonidazole were performed according to the literature [20]. Briefly, deparaffinized sections were to antigen retrieval in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0, at 90°C for 20 minutes), incubated in 50 mM glycine in PBS (pH 3.5) for 5 minutes and permeablized in 0.3% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes. After blocking, sections were incubated with mouse FITC-labeled anti-pimonidazole antibody (NPI, Burlington, MA) and labeled by anti-mouse IgG conjugated to HRP (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). The signal was amplified using TSA biotin system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and labeled by Alexa488-conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) followed by mounting with Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were captured by a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscopy with appropriate laser and filter settings and processed by LSM510 software (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). The acquired images were measured and the threshold was determined based on the histograms. The number of fluorescence positive cells were counted using Image J software (National Institutes of Health).

Immunostaining

Paraffin sections of decalcified femurs were labeled with anti-HIF-1α (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), anti-VEGF, anti-MMP14 (MT1-MMP) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) or rabbit IgG at matched concentration. Donkey biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was used for secondary antibodies followed by TSA biotin system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) for signal enhancement, and Alexa488 conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) for fluorescence or 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for immunohistochemistry. Images for fluorescence were captured by a confocal microscopy and processed by LSM510 software (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). For immunohistochemistory, an Axio Scope with AxioVision software (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) was used. The acquired images were measured and the threshold was determined based on the histograms. The number of fluorescence positive cells was counted or % of fluorescence positive area was analyzed using Image J software (National Institutes of Health).

Flow Cytometry

After euthanasia, legs were cut and attached muscles were stripped quickly. The femurs and tibiae were flushed with ice-cold DPBS/2% FCS. Single cell suspension was obtained by gently passing through 23G needles. Unfractionated Cells were stained with Lineage cocktail antibodies (Gr-1, CD11b, Ter119, B220 and CD3e) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and MMP14 (MT1-MMP) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). The cells were then washed, resuspended in 2 µg/ml propidium iodide in DPBS/2% FCS, and analyzed by a flow cytometer (DAKO ADP Cyan) in Research Resources Center in University of Illinois at Chicago. Summit (DAKO North America, Carpinteria, CA) or FlowJo 7.6 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) software was used for population analysis. For apoptosis detection, FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) was used, as describe in the manufacturer’s instructions. Peripheral blood was drawn from retro-orbital cavities under anesthesia and was separated to form the buffy-coat. The number of circulating leukocyte or total BM cells was counted manually in the cell suspension from the buffy-coat or tibiae, respectively, using hemocytometer.

Flow Cytometric Cell separation

Gr-1+, Lin− or cKit+/Lin− cells were sorted by MoFlo fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) (DAKO Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA) located in the research resource center at University of Illinois at Chicago from BM mononuclear cells separated by density gradient with Histopaque1083 (Sigma-Aldrich St. Louis, MO). Labeling was performed with Pacific blue conjugated anti-Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), biotinylated Lineage cocktail antibodies, and APC conjugated anti-cKit (2B8) antibodies (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Streptavidin-Alexa488 was used for Lineage detection.

Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) analysis

Total RNA was prepared from cells using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription was carried out using high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) or SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). The real-time PCRs were run on an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) in the SYBR Green PCR kit and the QuantiTect Primer Assay (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for specific genes. Expression of genes was normalized and expressed as fold-changes relative to beta-actin unless otherwise indicated.

Colony-Forming Unit (CFU) assay

Total bone marrow cells (104 per well) were plated in 6-well plates with 1.5 ml of methylcellulose-based medium (Methocult (M3434), StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) and colonies (>50 cells) were scored at day 12. CFU was normalized by total BM cell number counted manually using hemocytometer.

Gelatin Zymography

BM plasma was collected by flushing femurs with a total of 0.5 ml PBS. After spinning, supernatants were analyzed for metalloproteinase activity by gelatinolytic zymography, as described [21].

Statistical Analyses

Comparison between groups was analyzed by unpaired Student 2-tailed t test (2 groups) or ANOVA for experiments with more than 2 subgroups followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis. P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

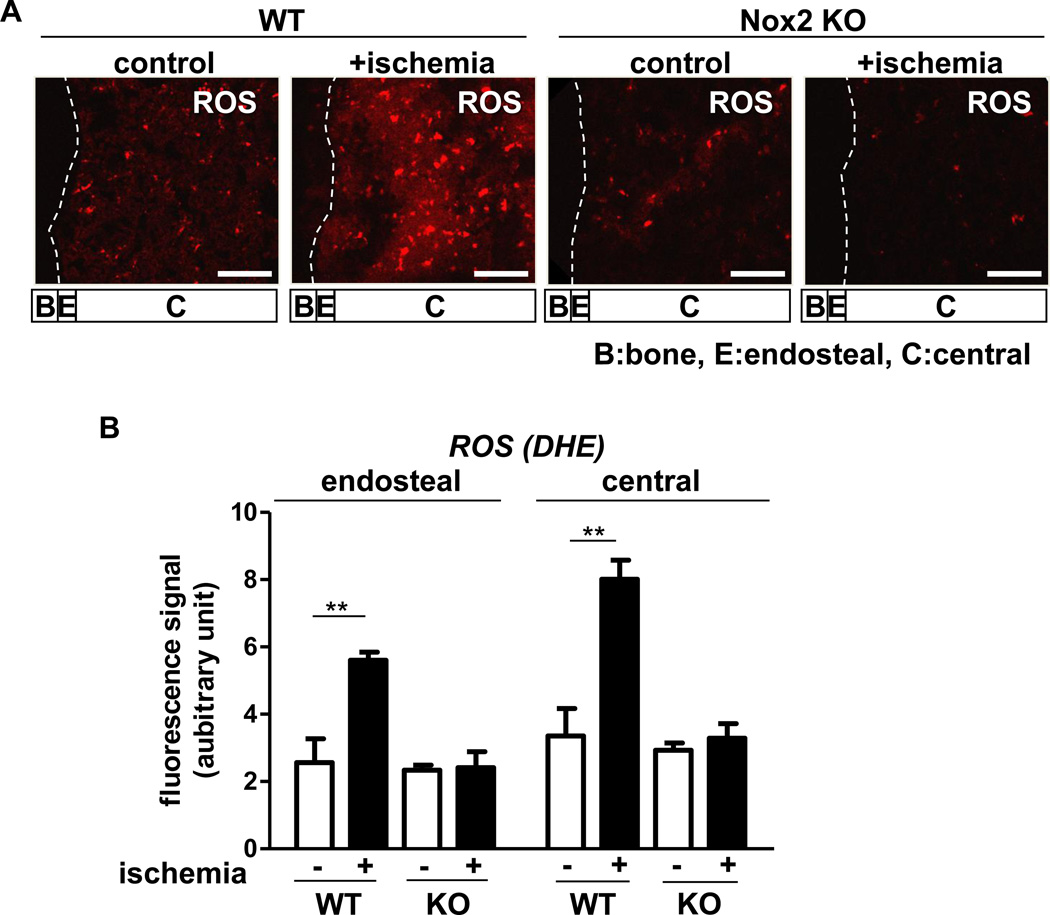

Nox2 is involved in hindlimb ischemia-induced increase in O2•− production in the endosteal and central BM in situ

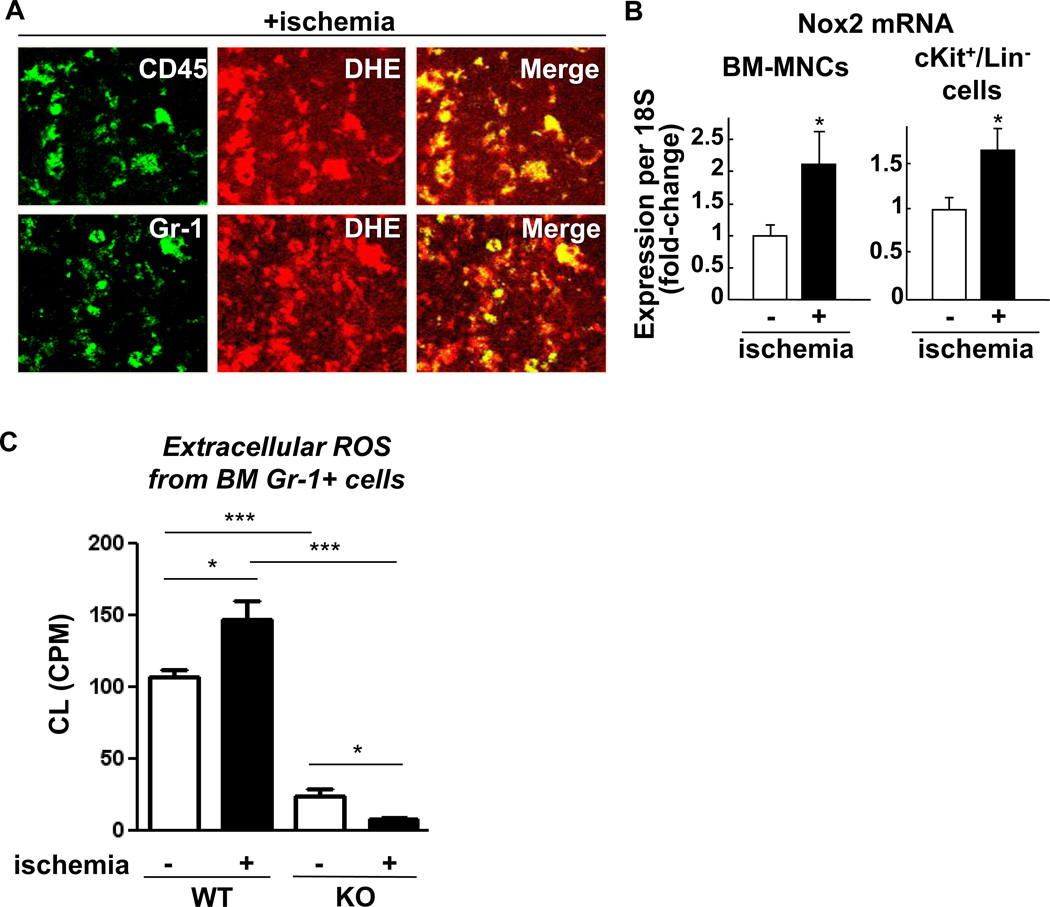

To determine the role of Nox2 in BM microenvironment during postnatal neovascularization, we examined the spatial distribution of O2•−in the BM tissue in situ in response to hindlimb ischemia in wild type (WT) mice and Nox2−/− mice which impair post-ischemic angiogenesis [19, 22]. To eliminate a post-harvesting phenomenon which may influence the measurement of O2•−in the BM, we injected O2•−detecting dye, dihydroethidium (DHE), into the mice before sacrifice [23]. Figure 1 shows that hindlimb ischemia significantly increased DHE staining in the central BM and at lesser extent in endosteal region defined as within 50 µm from the bone surface in WT mice, which were almost completely inhibited in Nox2−/− mice. Co-localization analysis for DHE positive signals with hematopoietic maker CD45, myeloid maker Gr-1 in BM tissues shows that majority of ROS producing cells in BM after hindlimb ischemia were differentiated myeloid cells (Figure 2A). Hindlimb ischemia also significantly increased Nox2 mRNA in both BM-MNCs and cKit+Lin− BM progenitor cells (Figure 2B). The extent of Nox2 gene expression in Gr-1+ cells was much higher than that in cKit+Lin− cells (4.38 fold). Since we found that Gr-1+ cells are major ROS producing cells in BM tissue in response to hindlimb ischemia, we measured ROS production in isolated Gr-1+ BM cells from WT and Nox2−/− mice using isoluminol assay. Figure 2C shows that hindlimb ischemia significantly increased ROS production in WT Gr-1+ cells, which was almost completely abolished in Nox2−/− Gr-1+ cells with significant decrease in basal ROS levels.

Figure 1. Nox2 is involved in O2•− production in bone marrow (BM)in situ in response to hindlimb ischemia.

A, representative images of superoxide (O2•−) production in BM of femur from wild-type (WT) or Nox2 knockout (KO) mice subjected to hindlimb ischemia on the contralateral leg (+ischemia (day 3)) or without hindlimb ischemia (control). To detect O2•− in situ, dihydroethidium (DHE) was injected 60 minutes before tissue harvest. Long bone surface is shown by dotted lines. Images were taken by confocal microscopy with 20X objective lens. Bars show 100 µm. Bone (B), approximate endosteal (E) (defined as 50 µm apart from the bone surface) and central (C) BM regions are indicated. B, a graph represents the mean fluorescence intensity of DHE subtracted by background signals in indicated regions of BM from randomly selected 3 areas from each mouse and 3 independent experiments were performed. All data shown are mean+SE and *p<0.01.

Figure 2. Gr-1+ myeloid cells are major source of hindlimb ischemia-induced O2•− in BM in situ.

A, the femur sections from wild-type (WT) mice with contralateral hindlimb ischemia (+ischemia (day 3)) and with the injection of O2•− detecting dye dihydroethidium (DHE) (shown in Figure 1) were further immunolabeled with anti-CD45 or -Gr-1 antibodies. The images were taken from the central BM regions shown in Figure 1A using confocal microscopy with 63X objective lens. B, freshly isolated BM mononuclear cells or cKit+/Lin progenitor cells from mice with or without hindlimb ischemia were analyzed for Nox2 mRNA expression by real-time PCR (n=3–4 in each group, *p<0.05). C, the extracellular release of O2•− from 106 Gr-1+ cells freshly isolated from the indicated BM was measured by isoluminol-amplifled chemiluminescence (CL) given as CPM (counts per minutes) (n=4 in each group, *p<0.05 and ***p<0.001). All data shown are mean+SE.

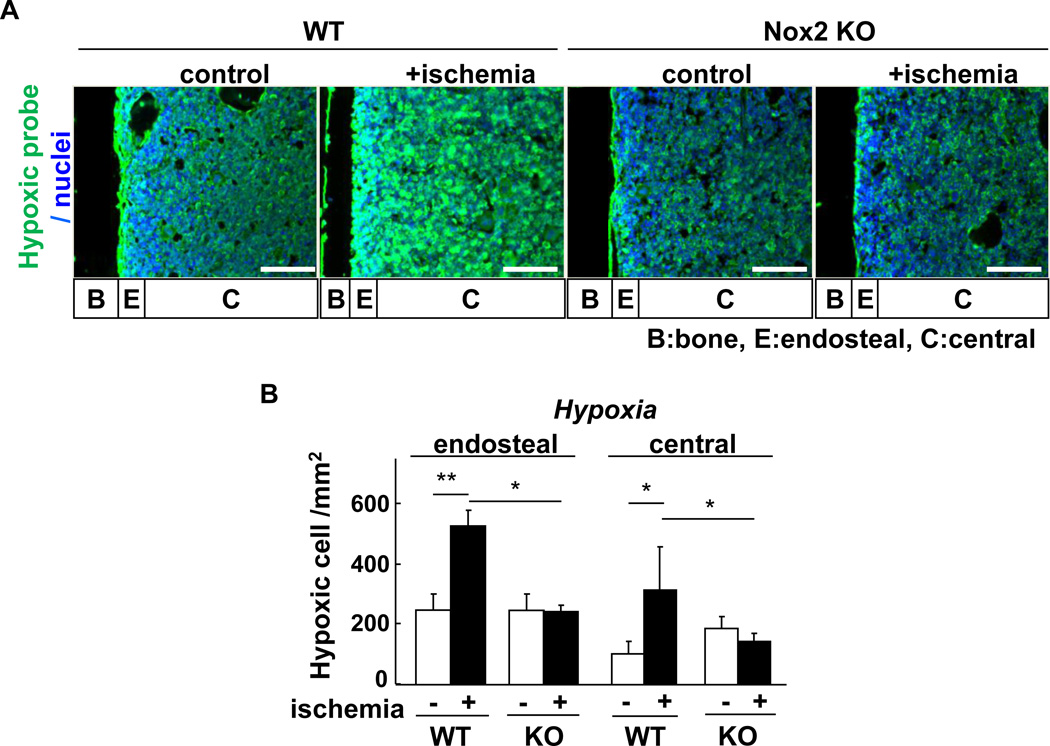

Hindlimb ischemia promotes hypoxia expansion and increases HIF-1α and VEGF expression throughout the BM, in a Nox2-dependent manner

Since oxygen is consumed to produce O2•− by activation of NADPH oxidase, we next examined the role of Nox2 in the spatial distribution of hypoxia in BM in response to hindlimb ischemia. For this purpose, we injected a hypoxic bioprobe, pimonidazole, which detects low O2 tension less than 1.3% [20]. Figure 3 shows that without hindlimb ischemia, a majority of pimonidazole-positive cells was preferentially incorporated in the hypoxic endosteal area adjacent to long bone surface while its staining is lower in the central BM area. In response to hindlimb ischemia, the hypoxic area stained by pimonidazole was expanded throughout the BM, which was almost completely abolished in Nox2−/− mice (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Hindlimb ischemia increases hypoxic area in BM, in a Nox2-dependent manner.

A, mice were injected with pimonidazole 3 hours prior to sacrifice. Femur sections from wild-type (WT) or Nox2 knockout (KO) mice subjected to hindlimb ischemia (+ischemia (day 3)) or without hindlimb ischemia (control) were stained with anti-pimonidazole monoclonal antibody (green) and 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to visualize nuclei (blue). Bars show 100 µm. Bone (B), endosteal (E) (defined as 50 µm apart from the bone surface) and central (C) regions are indicated. B, quantification of hypoxic cells was made by pimonidazole positive cell count per area in the endosteal and central BM regions from randomly selected 3 fields (n=3 mice in each group, *p<0.05 and **p<0.01). All results are mean+SE.

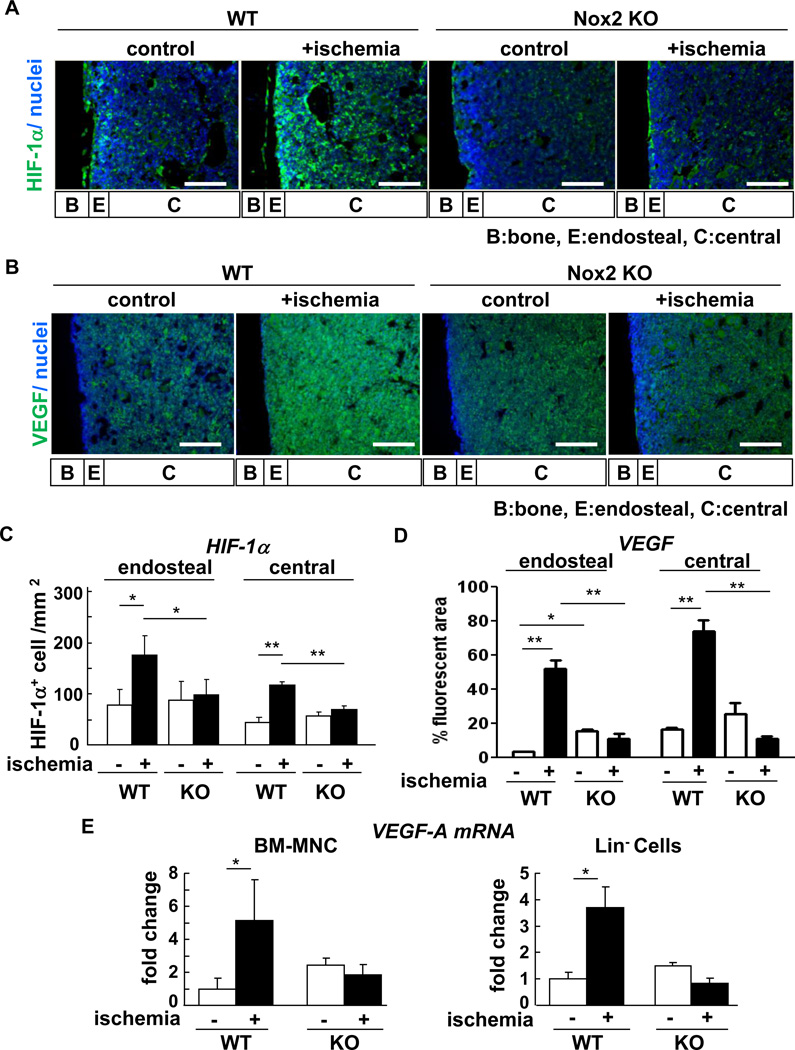

Since HIF-1α is a downstream target of hypoxia, we examined the distribution and expression of HIF-1α in the BM after hindlimb ischemia. Immunofluorescence analysis of BM tissue revealed that HIF-1α protein was highly expressed at the endosteum in basal state (Figure 4A and 4C). Hindlimb ischemia increased expression of HIF-1α in both endosteal and central BM, which was almost completely inhibited in Nox2−/− mice (Figure 4A and 4C). These results suggest that Nox2 activation may contribute to expansion of hypoxic BM microenvironment and increase in HIF-1α expression in response to tissue ischemia.

Figure 4. Hindlimb ischemia increases HIF-1a and VEGF expression in BM, in a Nox2-dependent manner.

A, femur Sections from wild-type (WT) or Nox2 knockout (KO) mice subjected to hindlimb ischemia (+ischemia (day 3)) or without hindlimb ischemia (control) were stained with anti-HIF-1α antibody (green) and with DAPI (blue). B, serial sections were stained with anti-VEGF antibody (green) and DAPI (blue). Original images were taken by fluorescent microscope with 20X objective lens. Bars show 100 µm. Bone (B), endsteal (E) (defined as 50 µm apart from the bone surface) and central (C) regions are indicated. C, quantification of HIF-1a were made by HIF-1α positive cells per area in the endosteal and central BM regions from randomly selected 3 fields (n=3 mice in each group, *p<0.05 and **p<0.01). D, quantification of VEGF were made by % VEGF stained area in the endosteal and central BM regions from randomly selected 3 fields (n=3 mice in each group, *p<0.05 and **p<0.01). E, freshly isolated BM mononuclear cells (MNCs) and Lin- progenitor cells from mice with or without hindlimb ischemia were analyzed for Nox2 mRNA expression by real-time PCR (n=3 in each group, *p<0.05). All results are mean+SE.

We then examined the expression of VEGF protein, one of the key HIF-α target genes inducing stem cell mobilization, using immunostaining in BM tissue. We found that VEGF expression was increased and expanded in whole BM following hindlimb ischemia, which was almost completely inhibited in Nox2−/− mice (Figure 4B and 4D). Furthermore, VEGF mRNA expression in both BM-MNC and Lin- progenitor cells was significantly upregulated following hindlimb ischemia, which was abolished in Nox2−/− mice (Figure 4E). Basal expression of VEGF protein and mRNA were rather increased in Nox2−/− BM tissue, BM-MNC and progenitor cells presumably due to compensatory mechanism. These results suggest that there is causal relationship between Nox2-ROS and hypoxia/HIF1-α/VEGF pathway in BM microenvironment in response to hindlimb ischemia.

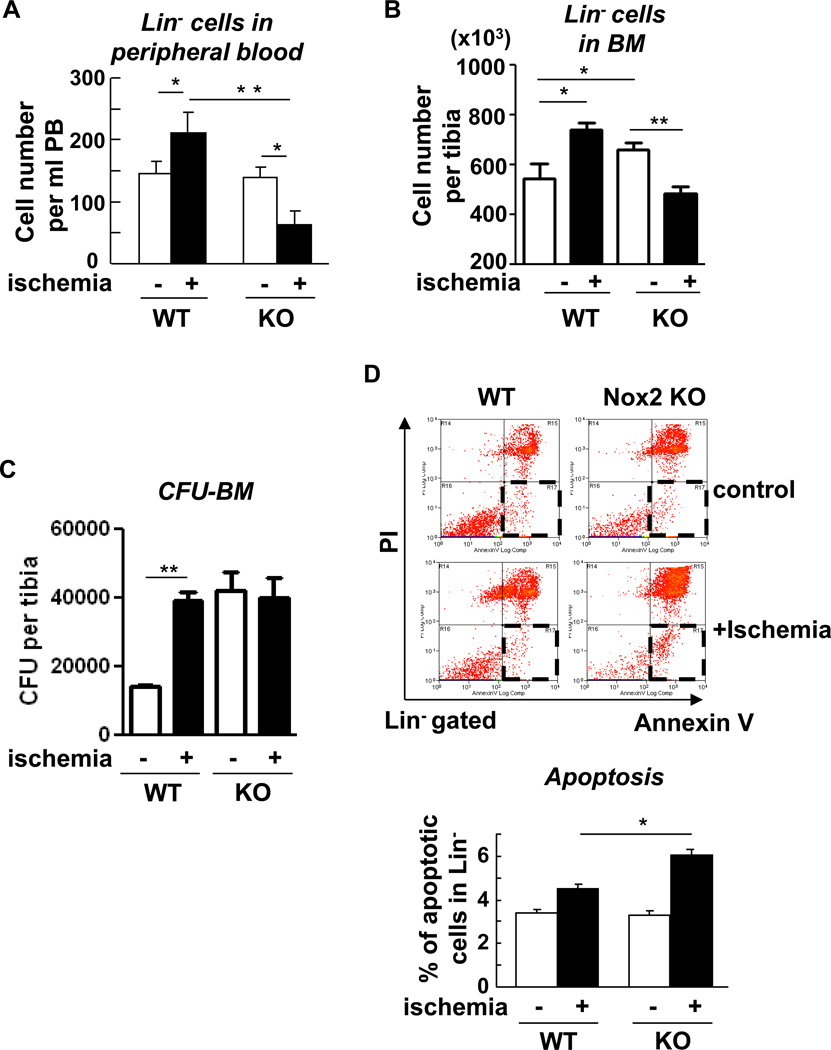

Nox2 is involved in promoting cell expansion and survival following hindlimb ischemia, thereby stimulating mobilization of Lin progenitor cells

Since hypoxia and HIF-1α in BM microenvironment may regulate stem/progenitor cell function and mobilization [20], we next examined the role of Nox2 in Lin- progenitor cell mobilization after hindlimb ischemia. Figure 5A shows that the number of circulating Lin− progenitor cells in peripheral blood was increased following hindlimb ischemia, which was significantly inhibited in Nox2−/− mice (Figure 5A). Under this condition, the pool size of Lin− progenitor cells in the BM, as measured by flow cytometry analysis (Figure 5B) and colony forming unit (CFU) assay (Figure 5C) was significantly increased following hindlimb ischemia. Although basal progenitor pool was significantly higher in Nox2−/− BM cells, ischemia-induced enhancement of progenitor cell expansion was markedly inhibited (Figure 5B and 5C). Thus, Nox2-mediated increase in hypoxic BM microenvironment may promote progenitor cell expansion, thereby stimulating their mobilization from BM after ischemic injury. To address the underlying mechanism, we examined the role of Nox2 in cell survival and proliferation of BM Lin- progenitor cells. Flow cytometry analysis with Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) staining shows that apoptotic cells (annexin V+/propidium iodide−) were significantly increased in Nox2−/− mice following hindlimb ischemia, as compared to those in WT mice (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Nox2 is involved in mobilization, expansion and survival of Lin progenitor cells in response to hindlimb ischemia.

A, circulating level of Lin progenitor cells was enumerated based on total leukocyte count and flow cytometry analysis in peripheral blood obtained from wild-type (WT) or Nox2 knockout (KO) mice with (+ischemia (day 3)) or without (control) hindlimb ischemia (n=6 in each group, *p<0.05 and **p<0.01). B, Lin progenitor cell numbers in tibia was enumerated based on total cell count per tibia and flow cytometry analysis in unfractionated BM cells obtained from wild-type (WT) or Nox2 knockout (KO) mice with or without hindlimb ischemia (n=6 in each group, *p<0.05). C, colony-forming unit (CFU) assay was performed using semisolid methylcellulose medium. CFU per tibia calculated based on total number of BM nucleorated cells is shown. Data are from the duplicates assays from 3 mice in each group (*p<0.05). D, flow cytometry analysis for propidium iodide (PI) and annexin V staining combined with Lin surface maker staining on fleshly isolated BM cells from femurs of WT or Nox2 KO mice with (+ischemia (day 3)) or without (control) hindlimb ischemia. Apoptotic cells were defined by PI negative and annexin V positive cells (red square at right lower quadrants). Percentage of apoptotic cells (apoptotic cells/<live cells (left lower quadrant) + apoptotic cells> X100) was calculated (n=4 in each group, *p<0.05). All results are mean+SE.

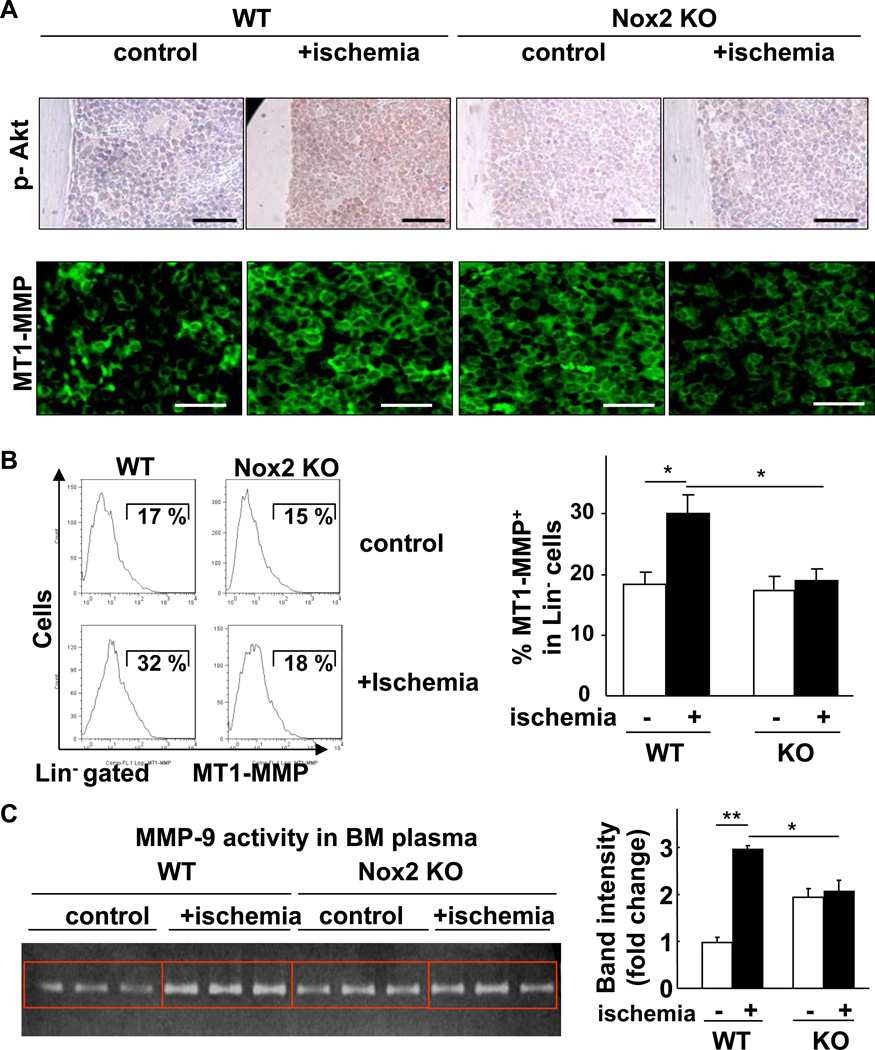

Nox2 is involved in Akt phosphorylation and MMPs activation in BM microenvironment in response to hindlimb ischemia

Since Akt is shown to be involved in cell survival and HIF-1α induction [24, 25], we examined the role of Nox2 in Akt activation in BM tissue following hindlimb ischemia. As shown in Figure 6A, immunostaining with p-Akt antibody on BM section reveals that hindlimb ischemia markedly increased phosphorylation of Akt in entire BM, which was almost completely blocked in Nox2−/− BM. Since proteolytic enzymes such as MT1-MMP and MMP-9 also play an essential role in regulating BM microenvironment, we thus examined the role of Nox2 in these enzymes expression or activity in BM following hindlimb ischemia. MT1-MMP expression in BM tissue was markedly enhanced by hindlimb ischemia, which was prevented in Nox2−/− BM (Figure 6A). Flow cytometry analysis further demonstrates that hindlimb ischemia increased cell surface MT1-MMP expression in Lin− BM progenitor cells, which was markedly inhibited in Nox2−/− mice (Figure 6B). In parallel, activity of MMP-9, a target of MT1-MMP [26] and a major regulator of stem and progenitor cells mobilization from BM [6], in BM plasma was increased by hindlimb ischemia, which was inhibited in Nox2−/− mice (Figure 6C). Basal MT1-MMP expression (Figure 6A) and MMP-9 activity (Figure 6C) were rather increased in Nox2−/− mice, which may be due to compensatory mechanisms. Of note, Akt is involved in increase in MT1-MMP expression in hematopoietic cells [27]. We also performed Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining of BM tissues and found that there was no morphological difference between WT and Nox2−/− mice (data not shown). Thus, these results suggest that Akt and MMPs are important downstream targets for Nox2-derived ROS in BM microenvironment that regulate progenitor cell function and mobilization in response to ischemic injury.

Figure 6. Nox2 regulates Akt phosphorylation and proteolytic enzymes (MT1-MMP and MMP-9) in BM in response to hindlimb ischemia.

A, in situ phosphorylated-Akt (Ser473) (brown in top) and MT1-MMP expression (green in bottom) in BM sections were shown by immunostaining. Wild-type (WT) or Nox2 knockout (KO) mice subjected to hindlimb ischemia (+ischemia (day 3)) or without hindlimb ischemia (control) were analyzed. Original images were taken by 20X (top) or 63X (middle and bottom) objectives. Bar: 50 µm in top and 30 µm in bottom. At least sections from 3 different mice in each group were analyzed. B, representative histogram of MT1-MMP expression in Lin- progenitor cells and % positive cells with signals above maximum intensity in isotype control samples (not shown) are shown. (n=3 mice in each group, *p<0.05). C, active MMP-9 in BM extracellular fluid was examined by gelatin zymography (n=3–4 in each group, *p<0.05). All data are shown as mean+SE.

Discussion

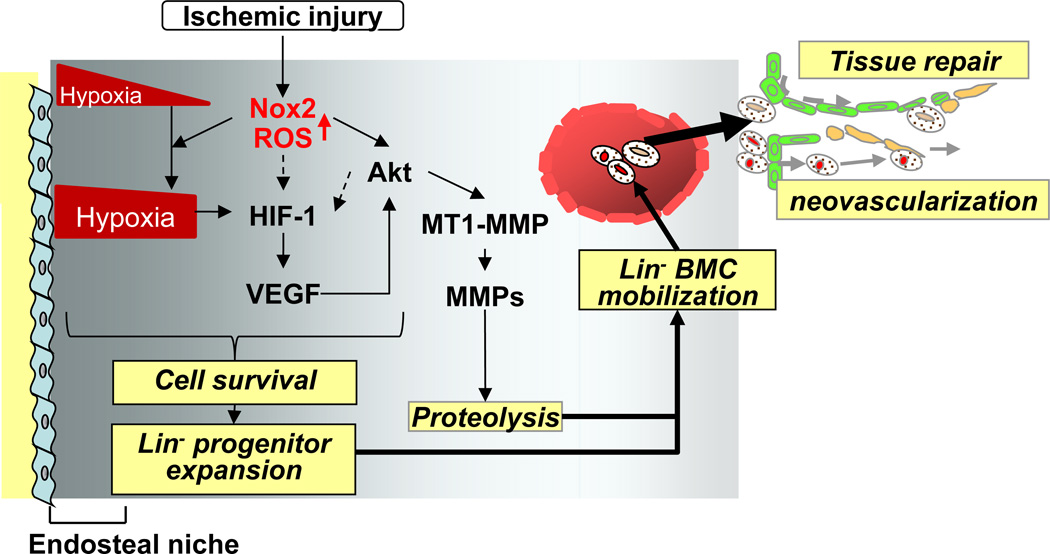

BM microenvironment regulated by hypoxia and proteolytic enzymes [5] plays an important role in stem/progenitor cell function and mobilization involved in postnatal neovascularization [2]. We previously reported that Nox2-derived ROS are involved in post-ischemic mobilization of BMCs and revascularization; however, role of Nox2 in regulating BM microenvironment in response to ischemic injury is entirely unclear. We show here that hindlimb ischemia increases: 1) Nox2-dependent ROS production mainly derived from Gr-1+ myeloid cells in entire BM in situ; 2) hypoxia expansion and its downstream HIF-1α and VEGF expression throughout the BM; 3) VEGF mRNA expression in differentiated myeloid cells and Lin- progenitor cells; 4) BM Lin- progenitor cell survival and expansion, and mobilization to the circulation; 5) Akt phosphorylation, MT1-MMP expression and MMP-9 activity in BM. All these ischemia-induced responses in BM tissue or progenitor cells are inhibited in Nox2−/− mice. Thus, Nox2-derived ROS play a critical role in regulating hypoxic niche and proteolytic enzyme activity in BM microenvironment, which is required for progenitor cell expansion and reparative mobilization in response to ischemia (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Nox2 regulates BM microenvironment involved in progenitor cell function and mobilization in response to tissue ischemic injury.

Following ischemic injury, ROS production is increased in entire BM in a Nox2-dependent manner, which is required for increasing hypoxic niche and its downstream HIF-1α and VEGF expression throughout the BM. Ischemic injury-induced Nox2-derived ROS also increase Akt phosphorylation and its downstream MT1-MMP expression and MMP-9 activity in BM. It is possible that ROS and Akt pathway are involved in HIF-1a expression through hypoxia-independent mechanism (dotted arrows). These Nox2-dependent alterations of BM microenvironment promote progenitor cell survival and expansion, thereby promoting their mobilization, leading to reparative neovascularization and tissue repair. (ROS; reactive oxygen species, BM; bone marrow, HIF-1α; hypoxia inducible factor-1α, MMP; matrix metalloproteinase and MT1-MMP; membrane type1-MMP also known as MMP14)

Stem and progenitor cells in the BM are localized in a microenvironment known as the stem cell ‘niche’, which includes the low oxygen endosteal niche mainly containing quiescent hematopoietic stem cells as well as more oxygenated vascular niche containing differentiated hematopoietic progenitors [3, 4]. Previous studies used isolated stem or progenitor cells to measure intracellular ROS levels under ambient oxygen ex vivo [10, 11, 28], which might not reflect the in vivo status of ROS levels. In the present study, in vivo injection of O2•− reactive probe, DHE, into the mice demonstrate that hindlimb ischemia robustly increases ROS production in BM tissues in situ predominantly at the central BM and at lesser extent at the endosteal regions, in a Nox2-dependent manner. Together with previous report [10] and as discussed below, it is conceivable that lower levels of ROS generation in endosteal niche may be associated with its hypoxic nature favoring primitive hematopoietic stem cells, while higher ROS production in central BM may link to high Nox2 expressing differentiated cells localized at vascular niche. We also found that ischemic injury-induced ROS in BM is mainly derived from differentiated myeloid cells including Gr-1+ cells and that Nox2 gene expression in Gr-1+ cells is about 4.4-fold higher than that in cKit+Lin− cells. Given the diffusible nature of ROS, these results suggest that hindlimb ischemia increases ROS mainly from Gr-1+ cells in BM in a Nox2-dependent manner, which may create oxidative microenvironment to regulate BM stem cell niche.

Hypoxic microenvironment is an important determinant for stem/progenitor function in the BM [29, 30]. Since oxygen is a source for O2•−induced by NADPH oxidase activation, we investigated the role of Nox2 in the spatial distribution of hypoxia in the BM following hindlimb ischemia. The present study using in vivo injection of hypoxic bioprobe pimonidazole, which cross-links to protein adducts at oxygen tension below 10 mmHg (less than 1.3% O2) [20] reveals that the endosteum at the bone BM interface is more hypoxic than the central BM in mice in the basal state. This is consistent with previous reports that the endosteal niche in steady-state is hypoxic, while the central BM is more oxygenated presumably due to the higher density of endothelial sinuses where oxygenated blood circulates. Hypoxic endosteal niche maintains hematopoietic stem cells in quiescent state which requires low oxygen tension and ROS level, while vascular niche with high oxygen tension contain more proliferative and differentiated stem/progenitor cells [3]. In current study, hindlimb ischemia expands low oxygen (hypoxic) area throughout the BM, in a Nox2-dependent manner. In line with our results, granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) or cyclophosphamide (CY), which stimulates mobilization of stem/progenitor cells, has been shown to increase hypoxia in the BM [20]. Of note, G-CSF and CY-induced stem cell mobilization was shown to be blunted in Nox2−/− mice [31]. In this study, the mechanism by which hindlimb ischemia increases hypoxia through Nox2 in contralateral legs remains unclear. It is possible that ischemic injury may increase cytokines, growth factors, neurotransmitters, and metabolites such as lactates, ROS themselves and inflammatory cells including Gr-1+ cells that produce large amounts of ROS in circulation, which may regulate contralateral BM microenvironment. The reason why BM becomes hypoxia by activation of Nox2 may be presumably due to the increase in oxygen consumption. Piccoli et al. [32] reported that the half of the oxygen consumption in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells is dependent on NADPH oxidase. In addition, the consumption of respiratory burst by NADPH oxidase in differentiated myeloid cells has been shown to contribute to local hypoxia [33]. Thus, Nox2 seems to be responsible for increased oxygen consumption and hypoxia in progenitor cells and Gr-1+ cells in mobilizing or inflammatory condition after hindlimb ischemia. Contribution of ROS-mediated vasoconstriction in the BM vasculature in reducing oxygen supply also cannot be excluded. Taken together, it is likely that hindlimb ischemia increases Nox2-dependent ROS-producing oxidative microenvironment, which in turn creates hypoxic niche throughout the BM by increasing oxygen consumption.

To address the consequence of increasing hypoxia in BM after hindlimb ischemia, we examined the expression of HIF-1α, a key downstream target of hypoxia involved in cell survival, angiogenesis [34] and hematopoietic stem cell function [15]. Immunofluorescence analysis of BM tissue sections shows that hindlimb ischemia increases expression of HIF-1α in entire BM tissue, in a Nox2-dependent manner. Consistent with our finding about the role of NADPH oxidase in HIF-1α level, it has been shown that lipopolysaccharide increases HIF-1α expression through activation of NADPH oxidase in myeloid cells [35]. Intermittent hypoxia activates HIF-1α through Nox2, which is required for hypoxia-induced ROS generation [36], suggesting that positive feed-forward mechanism among Nox2, hypoxia and HIF-1α may exist. Of note, HIF-1α is also regulated by ROS or kinase in a hypoxia-independent manner. It is reported that Nox-derived ROS promote HIF-1α stabilization in circulating hematopoietic stem cells by inhibiting von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) under normoxic conditions [37]. HIF-1α is also regulated by Akt as discussed below. In this study, we also found that hindlimb ischemia increases expression VEGF, a downstream target of HIF-1α involved in stem/progenitor cell mobilization and reparative neovascularization [38] in whole BM tissue, BM-MNCs and Lin−progenitor cells, in a Nox2-dependent manner. Diffusible staining of VEGF may be due to the possibility that VEGF is produced and secreted from various cell types including endothelial cells, progenitor cells and differentiated myeloid cells in BM following ischemic injury. Most recently, Rehn et al. reported that hypoxic niche regulates hematopoietic stem cell function via the hypoxia-VEGF axis [39]. Thus, these results suggest that Nox2-derived ROS play an important role for providing redox-sensitive BM microenvironment at least in part by increasing the hypoxia/HIF-1α/VEGF pathway in response to tissue ischemia.

ROS at physiological level act as signaling molecules to mediate various biological responses including stem/progenitor cell function. Hypoxia and HIF-1α influence stem/progenitor cells expansion by regulating cell survival and proliferation [15]. Stem cells can survive better under lower oxygen condition [15]. In this study, we show that Nox2 is required for ischemia-induced Lin− progenitor cell expansion in BM, as measured by Lin− progenitor cell pool using flow cytometry analysis and CFU assay. This is at least in part through increasing progenitor cell survival, thereby promoting their mobilization to circulation after ischemic injury. Of note, Nox2−/− mice had more basal Lin− progenitor cell pool (higher CFU) in unfractionated BMCs, which is consistent with previous report [31]. This may be in part through the compensatory increase in basal expression of VEGF in Nox2−/− BM (Figure 4). We found that BM transplantation of Nox2−/− BMCs was less efficient than that from WT mice (unpublished observations), indicating that Nox2−/− hematopoietic stem cells have lower reconstitution capacity after BM transplantation. This may in part due to homing defect of Nox2−/− BMCs to BM, since we observed that SDF-1-induced BMCs migration mediated through Akt is inhibited in Nox2−/−mice [19]. Akt is shown to be activated by hypoxia or ROS [40], and involved cell survival and HIF-1α expression and activity [24, 25, 41] as well as MT1-MMP expression in hematopoietic stem cells [27]. The present study shows that hindlimb ischemia markedly increases phosphorylation of Akt in the BM, which is almost completely blocked in Nox2−/− BM. Thus, Akt is an important downstream target for Nox2-derived ROS in BM microenvironment regulating stem and progenitor function and mobilization in response to ischemic injury. It is also possible that Nox2-mediated increase in hypoxia/HIF-1α/VEGF pathway may also indirectly activate Akt in the BM. This may represent a novel mechanism by which Nox2-derived ROS modulate stem/progenitor function by regulating BM microenvironment.

To further define the mechanism underlying Nox2-dependent mobilization of stem/progenitor cells from BM, we also examined the major proteolytic enzymes expression and activities in the BM in WT and Nox2−/− mice. Both MT1-MMP and MMP-9 play an important role in stem/progenitor cell migration or mobilization through inhibiting adhesive interactions necessary to retain stem/progenitor cells within the BM [6]. The present study demonstrates that hindlimb ischemia increases MT1-MMP expression in BM tissues and Lin− progenitor cells, in a Nox2-dependent manner. This is consistent with previous report that G-CSF increases MT1-MMP expression and decrease in its endogenous inhibitor, reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs (RECK) expression in human CD34+ progenitor cells through Akt-dependent pathway, thereby promoting their mobilization [27]. We also found that hindlimb ischemia decreases RECK expression in BM tissue, in a Nox2-dependent manner (unpublished observations). Furthermore, the present study shows that hindlimb ischemia increases MMP-9 activities in BM plasma, which is inhibited in Nox2−/− mice. Consistent with our data, low dose irradiation that potentially induces ROS promotes progenitor mobilization through MMP-9 and VEGF production [42]. Basal MT1-MMP expression in BM tissue, but not that in Lin− cells, as well as MMP-9 activity in BM plasma are increased in Nox2−/− mice, which is associated with compensatory increase in VEGF expression in BM, as described above. Of note, these steady state basal increases in proteolytic enzymes seem not to affect the number of circulating BM progenitors in Nox2−/− mice, while hindlimb ischemia-induced responses are blunted in these mice (Figure 6A). Thus ischemic injury-induced acute increase in MT1-MMP and MMP-9 may play more important role in mobilizing progenitor cells to circulation. Our results are consistent with the notion that Nox2-derived ROS play an important role in regulating proteolytic activity in BM in response to hindlimb ischemia, which may facilitate the stem/progenitor cell mobilization.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that ischemic injury increases ROS mainly derived from Gr-1+ myeloid cells through Nox2 activation in entire BM, which increases hypoxic niche and its downstream HIF-1α and VEGF expression as well as Akt and proteolytic enzyme activity in BM tissue. These Nox2-dependent alterations of BM microenvironment promote Lin- progenitor cell survival and expansion, thereby promoting their mobilization to circulation, leading to reparative neovascularization and tissue repair (Figure 7). This study should provide insights into redox regulation of BM microenvironment as a potential therapeutic strategy for treatment of various ischemic diseases [2, 13, 43–45].

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Nihal Kaplan for technical assistance and helpful comments and discussions. This work was supported by funds from National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 Heart and Lung (HL)077524, HL077524-S1 (to M.U.-F.) and HL070187 (to T.F.), American Heart Association (AHA) Grant-In-Aid 0755805Z (to M.U.-F.), AHA National Center Research Program (NCRP) Innovative Research Grant 0970336N (to M.U.-F) and AHA Post-doctoral Fellowship 09POST2250151 (to N.U.).

Grants: NIH HL077524, HL077524-S1 (to M.U.-F.) and HL070187 (to T.F.), AHA Grant-In-Aid 0755805Z (to M.U.-F.), NCRP Innovative Research Grant 0970336N (to M.U.-F) and 09POST2250151 (to N.U.).

Footnotes

Norifumi Urao: Conception and design, financial support, Collection and/or assembly of data, Data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and Final approval of manuscript

Ronald D. McKinney: Administrative support, Collection of data, Provision of study material and Final approval of manuscript

Tohru Fukai: Financial support, Data analysis and interpretation, and Final approval of Manuscript

Masuko Ushio-Fukai: Financial support, Conception and design, Data analysis and interpretation, Manuscript writing and Final approval of manuscript

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Werner N, Kosiol S, Schiegl T, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and cardiovascular outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:999–1007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dimmeler S. Regulation of bone marrow-derived vascular progenitor cell mobilization and maintenance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1088–1093. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.191668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson A, Trumpp A. Bone-marrow haematopoietic-stem-cell niches. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:93–106. doi: 10.1038/nri1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin T, Li L. The stem cell niches in bone. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1195–1201. doi: 10.1172/JCI28568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiel MJ, Morrison SJ. Uncertainty in the niches that maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:290–301. doi: 10.1038/nri2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rafii S, Avecilla S, Shmelkov S, et al. Angiogenic factors reconstitute hematopoiesis by recruiting stem cells from bone marrow microenvironment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;996:49–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:221–233. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itoh Y, Seiki M. MT1-MMP: a potent modifier of pericellular microenvironment. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ushio-Fukai M. Redox signaling in angiogenesis: role of NADPH oxidase. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jang YY, Sharkis SJ. A low level of reactive oxygen species selects for primitive hematopoietic stem cells that may reside in the low-oxygenic niche. Blood. 2007;110:3056–3063. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-087759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tothova Z, Kollipara R, Huntly BJ, et al. FoxOs are critical mediators of hematopoietic stem cell resistance to physiologic oxidative stress. Cell. 2007;128:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sardina JL, Lopez-Ruano G, Sanchez-Sanchez B, Llanillo M, Hernandez-Hernandez A. Reactive oxygen species: Are they important for haematopoiesis? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haneline LS. Redox regulation of stem and progenitor cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1849–1852. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosokawa K, Arai F, Yoshihara H, et al. Function of oxidative stress in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cell-niche interaction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;363:578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suda T, Takubo K, Semenza GL. Metabolic regulation of hematopoietic stem cells in the hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:298–310. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piccoli C, D'Aprile A, Ripoli M, et al. Bone-marrow derived hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells express multiple isoforms of NADPH oxidase and produce constitutively reactive oxygen species. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:965–972. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan J, Cai H, Tan WS. Role of the plasma membrane ROS-generating NADPH oxidase in CD34+ progenitor cells preservation by hypoxia. J Biotechnol. 2007;130:455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ushio-Fukai M, Urao N. Novel role of NADPH oxidase in angiogenesis and stem/progenitor cell function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2517–2533. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urao N, Inomata H, Razvi M, et al. Role of nox2-based NADPH oxidase in bone marrow and progenitor cell function involved in neovascularization induced by hindlimb ischemia. Circ Res. 2008;103:212–220. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levesque JP, Winkler IG, Hendy J, et al. Hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization results in hypoxia with increased hypoxia-inducible transcription factor-1 alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor A in bone marrow. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1954–1965. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galis ZS, Asanuma K, Godin D, Meng X. N-acetyl-cysteine decreases the matrix-degrading capacity of macrophage-derived foam cells: new target for antioxidant therapy? Circulation. 1998;97:2445–2453. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.24.2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tojo T, Ushio-Fukai M, Yamaoka-Tojo M, Ikeda S, Patrushev NA, Alexander RW. Role of gp91phox (Nox2)-containing NAD(P)H oxidase in angiogenesis in response to hindlimb ischemia. Circulation. 2005;111:2347–2355. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000164261.62586.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brennan AM, Suh SW, Won SJ, et al. NADPH oxidase is the primary source of superoxide induced by NMDA receptor activation. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:857–863. doi: 10.1038/nn.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao N, Ding M, Zheng JZ, et al. Vanadate-induced expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway and reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31963–31971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200082200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi YK, Kim CK, Lee H, et al. Carbon monoxide promotes VEGF expression by increasing HIF-1alpha protein level via two distinct mechanisms, translational activation and stabilization of HIF-1alpha protein. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32116–32125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.131284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han YP, Yan C, Zhou L, Qin L, Tsukamoto H. A matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation cascade by hepatic stellate cells in trans-differentiation in the three-dimensional extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12928–12939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700554200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vagima Y, Avigdor A, Goichberg P, et al. MT1-MMP and RECK are involved in human CD34+ progenitor cell retention, egress, and mobilization. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:492–503. doi: 10.1172/JCI36541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ito K, Hirao A, Arai F, et al. Regulation of oxidative stress by ATM is required for self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2004;431:997–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature02989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eliasson P, Jonsson JI. The hematopoietic stem cell niche: low in oxygen but a nice place to be. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222:17–22. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohyeldin A, Garzon-Muvdi T, Quinones-Hinojosa A. Oxygen in stem cell biology: a critical component of the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Os R, Robinson SN, Drukteinis D, Sheridan TM, Mauch PM. Respiratory burst of neutrophils is not required for stem cell mobilization in mice. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:695–699. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piccoli C, Ria R, Scrima R, et al. Characterization of mitochondrial and extra-mitochondrial oxygen consuming reactions in human hematopoietic stem cells. Novel evidence of the occurrence of NAD(P)H oxidase activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26467–26476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500047200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edlund J, Fasching A, Liss P, Hansell P, Palm F. The roles of NADPH-oxidase and nNOS for the increased oxidative stress and the oxygen consumption in the diabetic kidney. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26:349–356. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) pathway. Sci STKE. 2007;2007:cm8. doi: 10.1126/stke.4072007cm8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishi K, Oda T, Takabuchi S, et al. LPS induces hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activation in macrophage-differentiated cells in a reactive oxygen species-dependent manner. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:983–995. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan G, Khan SA, Luo W, Nanduri J, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 mediates increased expression of NADPH oxidase-2 in response to intermittent hypoxia. J Cell Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jcp.22640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piccoli C, D'Aprile A, Ripoli M, et al. The hypoxia-inducible factor is stabilized in circulating hematopoietic stem cells under normoxic conditions. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3111–3119. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rey S, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1-dependent mechanisms of vascularization and vascular remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;86:236–242. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rehn M, Olsson A, Reckzeh K, et al. Hypoxic induction of vascular endothelial growth factor regulates murine hematopoietic stem cell function in the low-oxygenic niche. Blood. 2011;118:1534–1543. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beitner-Johnson D, Rust RT, Hsieh TC, Millhorn DE. Hypoxia activates Akt and induces phosphorylation of GSK-3 in PC12 cells. Cell Signal. 2001;13:23–27. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(00)00128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dayan F, Bilton RL, Laferriere J, et al. Activation of HIF-1alpha in exponentially growing cells via hypoxic stimulation is independent of the Akt/mTOR pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218:167–174. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heissig B, Rafii S, Akiyama H, et al. Low-dose irradiation promotes tissue revascularization through VEGF release from mast cells and MMP-9-mediated progenitor cell mobilization. J Exp Med. 2005;202:739–750. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krankel N, Spinetti G, Amadesi S, Madeddu P. Targeting stem cell niches and trafficking for cardiovascular therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;129:62–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grek CL, Townsend DM, Tew KD. The impact of redox and thiol status on the bone marrow: Pharmacological intervention strategies. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;129:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobayashi CI, Suda T. Regulation of reactive oxygen species in stem cells and cancer stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:421–430. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]