Abstract

Cystoid macular edema (CME) is a relatively common painless condition usually accompanied by blurred vision. The prevalence of CME varied from 5% to 47% depending on cause of pathology. There are several treatments available for ME including intravitreal use of bevacizumab that has been used in different doses in few studies. However, there is still scarcity of data available on the use of bevacizumab for the treatment of ME. A systematic review is needed to provide a foundational base to discuss and synthesize the available information on the effectiveness and safety of intravitreal bevacizumab in macular edema, so that recommendations and policies can be built regarding controversial use of bevacizumab in macular edema. We have planned to perform a systematic review with an objective to compare the effects of a single injection of 1.25 mg intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin) in the improvement of visual acuity, macular edema, and thickness with other interventions/controls for the treatment of macular edema at 3 and 6 months interval using randomized controlled trials. This is only a protocol of the review and we will be conducting a full length review, addressing the issue in future.

Keywords: Avastin, protocol, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Description of the condition

Macular edema (ME) is an abnormal thickening of the macula due to accumulation of excess fluid in the extracellular space of the retina.[1] It is a leading cause of irreversible vision loss,[2] in the occular conditions such as diabetic retinopathy,[3] venous occlusion,[4] uveitis,[5] after cataract surgery,[6] ocular inflammations, and branch retinal vein occlusion.[7] It is diagnosed by investigative tools such as fluorescein angiography (FA) and optical coherence tomography (OCT).[8] The most common forms of macular edema are cystoid macular edema and diabetic macular edema.

Cystoid macular edema (CME) is a relatively common painless condition usually accompanied by blurred vision.[1] It is diagnosed by biomicroscopy, fluorescein angiography, and/or optical coherence tomography and is observed as a fluid accumulation in multiple cyst-like spaces within macula.[1] It is frequently associated with various ocular conditions such as, cataract surgery and age-related macular degeneration (ARMD).[9] The prevalence of CME varies between 5% to 47% depending on its cause of pathology such as in patients with diagnosis of uveitis, retinitis pigmentosa, pars planitis, toxocariasis, after cataract surgery, and age-related macular degeneration its prevalence is 6.1%,[10] 9.45-44%,[11,12] 26.1-27%,[13,14] 47.4%,[15] 5%,[16] and 46%,[17] respectively.

The prognosis of CME varies according to its cause. Pseudophakic CME typically has the best prognosis.[9] Similarly, CME prognosis after retinal detachment is generally without complications.[18] However, despite its good prognosis persistent macular edema or multiple remissions and exacerbations can result in foveolar photoreceptor damage with permanent impairment of vision.[9] The risk of a person having CME can be decreased by avoiding intraoperative complications in ophthalmic surgery, such as posterior capsule rupture, vitreous loss, or dislocated lens.[9]

Diabetic macular edema (DME) is a common complication of diabetic retinopathy.[19] DME can be classified into diffuse macular edema, cystoid macular edema, and serous retinal detachment on the basis of OCT.[20] Diffuse macular edema is a general thickening caused by extensive capillary dilation,[21] while focal edema is caused primarily by focal leakage from specific vascular abnormalities, diagnosed by hard exudates.[21,22] The most common complication of DME is a subretinal fibrosis. Subretinal fibrosis is a vision-threatening condition that can occur in 2% of eyes with diabetic macular edema.[23] This poor prognosis is generally even refractive to focal laser therapy (best treatment available for DME).[24] A study by Markomichelakis et al. has shown the prevalence of DME was 54.8% in patients with macular edema.[5] DME mostly occurs in combinations with other ocular conditions such as vitreomacular adhesion.[25]

Macular edema is the final common phenotype of several pathophysiologic processes, and its effective management is based on the diagnosis and management of its cause.[1] There are various treatments available for macular edema such as NSAIDS, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, steroids, immunomodulators, hyperbaric oxygen, and vitreous surgery.[2] Laser photocoagulation is the treatment of choice in nondiffuse macular edema, whereas pharmacological agents such as NSAIDS have shown effectiveness in decreasing diffuse macular edema and improving visual outcome.[1] For, CME a combined treatment of NSAIDs and steroids have shown faster resolution than placebo. A study has also shown that treating with NSAIDs after cataract surgery decreases the risk of postoperative CME.[26]

Description of the intervention

A vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a potent inducer of vascular permeability that leads to macular edema.[27,28,29] Bevacizumab (Avastin R, a trademark of Genentech, Inc.) is a VEGF inhibitor,[30] which is a full length humanized monoclonal antibody IgG[31] approved for intravenous administration for the treatment of diseases such as metastatic colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, and glioblastoma multiforme.[29,32,33,34] There are no contraindications associated with using bevacizumab I/V; however, it should be given with precautions in patients with gastrointestinal perforations and hypertension.[35] Its adverse effects include proteinuria, wound complications, thromboembolic events, and hypertensive crisis.[35] The chemical formula of bevacizumab is C-6638 H-10160 N-1720 O-2108 S-44 and its molecular mass is approximately 149 kD.[35,36]

Bevacizumab has also been currently used by clinicians for treatment of choroidal neovascularization as an off-label use, as currently not approved by FDA (Food and Drug Administration, USA).[35] Many studies conducted on intravitreal use of bevacizumab have used a quantity of 1.25 mg using a 30-gauge needle.[37,38,39,40] Although, few studies have also used 2.5 mg of Avastin; however, both 1.25 and 2.5 mg have shown similar treatment efficacy.[41,42] Studies on its pharmacokinetics and dynamics have shown that a half-life of 1.25 mg of intravitreally injected bevacizumab was 2.8 and 12.3 days in the aqueous humor and serum respectively.[43] There is no information available on the metabolism, excretion, interaction, contraindications and adverse effects of intravitreal use of bevacizumab.[29,35]

How the intervention might work

A meta-analysis conducted by Andriolo et al. in 2009 has shown that use of bevacizumab alone or in combination with other treatments for the treatment of occular diseases is more effective than either photodynamic therapy, focal photocoagulation, or triamcinolone.[44] Bevacizumab has a potential role not only to prevent, but also reduce retinal thickness in patients with DME.[45] A study by Cordero et al. has found that a single intravitreal injection of bevacizumab is well tolerated and is associated with short-term improvement in visual acuity and retinal thickness in patients with CME.[46] Few randomized studies have also shown improvement of visual acuity and reducing macular thickness in patients with DME as well as improving visual acuity in patients with CME.[42,47,48,49]

However, there are few exceptions as well; a study by Picolla et al., 2008 has shown that a single intravitreal injection of triamcinolone is better than bevacizumab in the short-term management of refractory diabetic macular edema.[50] Further, another study showed that up to 12 weeks of treatment with intravitreal bevacizumab versus laser photocoagulation in patients with DME is not associated with a significant decrease in macular thickness.[47]

Why it is important to do this review

Macular edema in its various forms can be considered a leading cause of central vision loss in the developed world, and is of enormous medical and socioeconomic importance. [2.51],[52] Despite that ample studies have shown the effectiveness of bevacizumab in occular disorders[42,47,48,49] its intravitreal use is still not approved by FDA. One of the hindrances may be incomplete information regarding its metabolism, excretion, adverse effects, and drug interactions.[29,35] Second, studies showing effectiveness of bevacizumab have failed to make any firm recommendations or conclusions[37,49,53] as most of these studies were of short duration with no long-term follow ups.[45,47,53,54] Further, some of the inconclusive studies were conducted on small samples without sample size determination and thus may lack the statistical power to calculate the effect size.[48,55]

This issue is also important because many hospitals in different countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh and even few of the hospitals of countries such as US and UK are using this drug for occular diseases unofficially.[56] A systematic review is needed to provide a foundational base to discuss and synthesize the available information on the effectiveness and safety of intravitreal bevacizumab in macular edema, so that, recommendations and policies can be built regarding controversial use of bevacizumab in macular edema.

OBJECTIVES

The primary objective is to compare the effects of a single injection of 1.25 mg intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin) in the improvement of visual acuity, macular edema and thickness with other interventions/controls for the treatment of macular edema at three and six months interval using randomized controlled trials. The secondary objective is to compare the effects of a single injection of 1.25 mg intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin) in improving foveal thickness and macular volume, visual acuity, macular edema and thickness, and complications and adverse events with other interventions/controls for the treatment of macular edema at different time intervals using randomized controlled trials.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Selection criteria

Population

Studies enrolling participants with unilateral or bilateral macular edema of any type severity/grade irrespective of any age, gender, ethnicity, and type would be included. The justification of selection criteria is macular edema and in general has no racial, sexual, and age restricted predilection. The treatment effect of bevacizumab is not related to age and gender; however, age and gender subgroup analysis will be done keeping in view that only limited information on intravitreal use of bevacizumab is available.[35,36] There are two main types of macular edema that is cystoid macular edema and diabetic macular edema for which subgroup analysis will be conducted. There is no grading criteria available for macular edema. The diagnosis of macular edema will be based on retinal thickening, and/or intraretinal cysts in the foveal region determined by either optical coherence tomography (OCT), fluorescein dye or ophthalmoscope[1,8,21,22] by an ophthalmologist either in a tertiary care center or clinic.

Interventions

All studies using intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin) single injection of 1.25 mg (0.05 mL) will be included. This is a standard protocol followed in different institutions and supported by studies.[37,38,39,40] Any duration and timing of delivery of avastin will be accepted. However, studies will be excluded in which Avastin will be given as co-intervention that is in combination with other treatments agents, in order to avoid issues related to contamination of the intervention.

Controls

The comparison group will be any other anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) treatment, placebo, standard, or another intervention such as triamcinolone acetonide, laser treatment etc., Any duration, timing, frequency, and dosage of control will be accepted.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes. It includes:

Best corrected visual acuity[57] either measured by Snellen chart or measured by visual acuity scale[58] (log MAR) at 3 and 6 months.

Macular edema and thickness at 3 and 6 months. It will be measured by optical coherence tomography, fluorescein dye or ophthalmoscope.[1,8,21,22]

Secondary outcomes. It includes:

Adverse events

Adverse events included marked, moderate to transient anterior chamber reaction, subconjunctival hemorrhage, posterior vitreous detachment, foccular inflammation, increased intraocular pressure, retinal tears and detachment, cataract progression, and any other adverse effect within one year of treatment.

Quality of life measures and economic data

Quality of life by any validated measures would be summarized when reported in the included studies.[60] The review will include cost effectiveness, cost benefit, and cost utility analysis if available.

Studies

All included studies will be randomized controlled trials (RCT) of any duration, follow up, number of assessments or measurements. Randomized controlled trials including either simple or permuted (blocked) randomization and using methods such as random numbers table, random assignments generated by computer, coin-tossing, throwing dice, drawing of lots, dealing previously shuffled cards, or minimization will be included.[61,62] Quasi randomized controlled trials or nonrandomized controlled trials using methods such as date of birth, case record number, date of presentation, and other nonrandom methods such as preference of clinician, preference of study participants, or availability of intervention will not be included. For studies with incomplete information or using unclear methods such as, when the authors use a word of randomization but the process was not explained such as a random number table or a computer random number generator was not specified a contact with the corresponding author would be made.

Search method for identification of studies

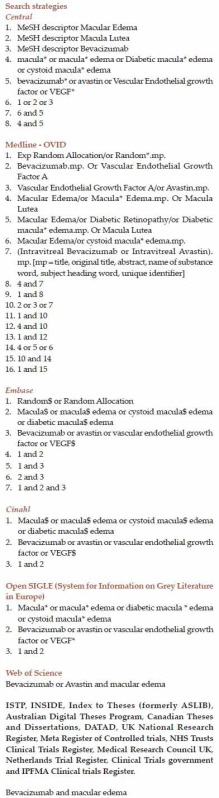

A search will be conducted based on key terms or MeSH descriptors of “macular edema,” “macula lutea,” “bevacizumab,” “macula* or macula* edema or diabetic macula* edema or cystoid macula* edema,” “bevacizumab* or avastin or Vescular Endothelial Growth factor or VEGF*” in Cochrane central register of controlled trials (CENTRAL) including cochrane library, Medline- OVID, EMBASE, Web of Science, CINAHL (Current Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) and Open SIGLE (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe). Conference proceedings will be located from ISTP (Index to Scientific and Technical Proceedings) and INSIDE (BL database of Conference Proceedings and Journals). Thesis and dissertation will be retrieved from Index to Theses (formerly ASLIB), Australian Digital Theses Program, Canadian Theses and Dissertations, DATAD - Database of African Theses and Dissertations and Dissertation Abstract Online (USA). Ongoing trails will be searched from UK National Research Register, Meta Register of Controlled Trials (mRCT), NHS Trusts Clinical Trials Register, Medical Research Council UK, Netherlands Trial Register, Clinical Trials government and IPFMA Clinical Trials Register. There would be no date or language restrictions. For non-English articles we will contact a certified translator and for the unpublished articles and dissertations we will contact the authors. The articles would also be searched from the reference list of the studies included in the review for information about further trials. The exact key words that will be used for each of the databases along with specific search strategy are attached as Appendix 1.

Selection of studies

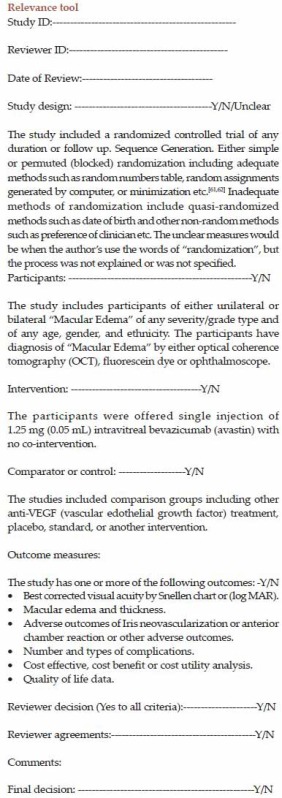

Two researchers will independently select and screen the titles and abstracts of the relevant articles identified by the systematic search strategies. Each researcher will independently classify the titles and abstracts of the relevant studies into include, exclude and unsure. Each researcher will also independently assess the full extract of the included and unsure articles and will further classify them into include, exclude, and unsure. For studies that will require further information we will contact the corresponding author requesting for further general descriptions. Finally both the researchers will compare their individual classifications and will discuss any discrepancies. In case of no mutual consensus in classification between the two authors, the final judgment regarding classification of studies will be made by the third researcher. The complete details of the selection criteria are attached as Appendix 2.

Data extraction and management

Two researchers would separately extract data from the selected studies into paper version of data extraction form. Any conflicts would be resolved by mutual discussion and further consulting with the third researcher if necessary. The extracted data would include reviewer, article number, author, year, funding, country, language, and reasons for exclusion. Participant characteristics included age, gender, cause and form of macular edema, duration, severity grade, diagnostic criteria used that is OCT, fluoresce in dye or ophthalmoscope and other co-morbid conditions would be recorded. Information regarding interventions and controls such as bevacizumab timing and duration, type of comparator or control, its dose, frequency, mode of delivery, duration, and timing will be noted. Sample size, methodological characteristics such as allocation concealment, blinding of patients, clinicians and outcome assessors, lost to follow up or missing data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias will be recorded. Primary and secondary outcomes, adverse events, quality of life data and any economical data along with statistical analysis techniques will also be recorded. The extracted data will be entered into Review Manager Software (Rev Man 5) by one of the reviewer and the other reviewer will verify the entries.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two researchers will assess risk of bias in included studies by using an assessment tool mentioned in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.[63] The criteria will include allocation concealment, blinding of patients, clinicians and outcome assessors, missing outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. Each reviewer will assess article on the basis of above characters and categorize each parameter into adequate, inadequate or unclear methods. Any discrepancies on grading would be solved by mutual discussion and consensus.

Measurement of treatment effect

Treatment effects will be measured in terms of types of data used in the studies following Deeks.[64]

Dichotomous data. It includes proportion of patients with improvement in best corrected visual acuity by three or more lines (equivalent of 15 letters), macular edema and thickness, foveal thickness and macular volume at 3, 6, and 12 months, adverse events and complications within 1 year. The type of macular edema will also be reported as dichotomous data. The dichotomous variables will be reported as risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data. The continuous data includes changes in visual acuity (log MAR), macular edema and thickness, foveal thickness, and macular volume at 3, 6, and 12 months. The continuous data will be reported either in mean (SD) or median (IQR) depending on assumptions of normality and weighted mean difference.[65]

Ordinal data. The number of complications and adverse events, economic data and quality of life, and grading of macular edema would be reported as ordinal data or rates data.

Counts data. The number of times adverse events and complications occurred within a person would also be given as counts data.

Unit of analysis issues. The unit of analysis will be the eye of an individual participation.[66] Most of the trials included will randomize a single eye or both eyes to the intervention.[67] If both eyes of a single participant are randomized to a single intervention, then each eye will be treated.[67] Crossover trails will be meta analyzed separately irrespective of whether they are also combined together and a sensitivity analysis will be conducted to support the results of how cross over trails were conducted.[68] Studies with co intervention and multi intervention will be excluded. Repeated assessments will be done at 3, 6, and 12 months.[69] For events that may reoccur within a single patient count data analysis will be conducted.[69]

Missing outcomes

Any missing data on the required outcomes would be gathered by contacting the corresponding author. For data that cannot be retrieved a multiple imputation method would be used and a sensitivity analysis would be applied to determine the potential impact of missing data in our results.[66] The potential impact of missing data will be also discussed in the discussion section.[66]

Heterogeneity, sub group analysis, data analysis, and sensitivity analysis

There is no evidence is available on the effect of bevacizumab in relation to age and gender; therefore, clinical diversity would not be of issue. However, a subgroup analysis would be performed to measure the effect of type of macular edema as well as affect of age and gender. Methodological diversity would be minimized by selecting only a single study design (RCT) and also by performing sensitivity analysis for the methodological quality of studies. However, as some argue argue that, since clinical and methodological diversity always occur in a meta-analysis, statistical heterogeneity is inevitable.[69] Therefore, heterogeneity will be addressed by using the I-squared test to assess the impact of intervention variability in different studies. Random-effect model would be used in the case of more than three trials and fixed effects in case of less than three trials.[65] In the case of heterogeneity value greater than 50%, meta analysis would not be performed and results will be presented in the tabular format.[65] However, investigations for heterogeneity of individual studies in terms of subgroup analysis or meta-regression would not be done in case of small number of studies.[67] Funnel plots would be used to assess the other means of heterogeneity only if more than 10 studies would be found.[66] Finally a sensitivity analysis will be performed to determine the impact of quality of studies on the findings.

APPENDIX 1

APPENDIX 2

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johnson MW. Perspective, etiology and treatment of macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tranos PG, Wickremasinghe SS, Stangos NT, Toupozis F, Tsinopoulos I, Pavesio CE. Macular edema. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49:470–90. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandello F, Pognuz R, Polito A, Pirracchio A, Menchini F, Ambesi M. Diabetic macular edema: Classification, medical and laser therapy. Semin Ophthalmol. 2003;18:251–8. doi: 10.1080/08820530390895262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catier A, Tadayoni R, Paques M, Erginay A, Haouchine B, Gaudric A. Characterization of macular edema from various etiologies by optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:200–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markomichelakis NN, Halkiadakis I, Pantelia E, Peponis V, Patelis A, Theodossiadis P. Patterns of macular edema in patients with uveitis: Qualitative and quantitative assessment using optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:946–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sourdille P, Santiago PY. Optical coherence tomography of macular thickness after cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25:256–61. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(99)80136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varano M, Scassa C, Ripandelli G, Capaldo N. New diagnostic tools for Macular Edema. Doc Ophthalmol. 1999;97:373–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1002448400495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sivaprasad S, McCluskey P, Lightman S. Intravitreal steroids in the management of macular oedema. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:722–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2006.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Telander DG, Cessna CT. Macular edema, Irvine-Gass. [Last accessed on 2010 Mar 5]. Available from: http://www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/1224224-overview .

- 10.Prieto-del-Cura M, Gonzalez-Guijarro J. Complications of uveitis: Prevalence and risk factors in a serie of 398 cases. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2009;84:523–8. doi: 10.4321/s0365-66912009001000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giusti C, Forte R, Vingolo EM. Clinical pathogenesis of macular holes in patients affected by Retinitis Pigmentosa. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2002;6:45–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adackapara CA, Sunness JS, Dibernardo CW, Melia BM, Dagnelie G. Prevalence of cystoid macular edema and stability in oct retinal thickness in eyes with retinitis pigmentosa during a 48-week lutein trial. Retina. 2008;28:103–10. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31809862aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donaldson MJ, Pulido JS, Herman DC, Diehl N, Hodge D. Pars planitis: A 20-year study of incidence, clinical features, and outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:812–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortega-Larrocea G, Arellanes-Garcia L. Pars planitis: Epidemiology and clinical outcome in a large community hospital in Mexico City. Int Ophthalmol. 1995;19:117–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00133182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart JM, Cubillan LD, Cunningham ET., Jr Prevalence, clinical features, and causes of vision loss among patients with ocular toxocariasis. Retina. 2005;25:1005–13. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200512000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu TT, Amini L, Leffler CT, Schwartz SG. Cataracts and cataract surgery in mentally retarded adults. Eye Contact Lens. 2005;31:50–3. doi: 10.1097/01.icl.0000134520.49016.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ting TD, Oh M, Cox TA, Meyer CH, Toth CA. Decreased visual acuity associated with cystoid macular edema in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthal. 2002;120:731–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonnet M, Payan X. Long-term prognosis of cystoid macular edema after microsurgery of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. J Fr Opthalmol. 1993;16:259–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parravano M, Menchini F, Virgili G. Antiangiogenic therapy with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor modalities for diabetic macular oedema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD007419. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007419.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iannetti L, Accorinti M, Liverani M, Caggiano C, Abdulaziz R, Pivetti-Pezzi P. Optical coherence tomography for classification and clinical evaluation of macular edema in patients with uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2008;16:155–60. doi: 10.1080/09273940802187466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goatman KA. A reference standard for the measurement of macular oedema. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:1197–202. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.095885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunha-Vaz JG, Lobo C, Sousa JC, Oliveiros B, Leite E, Faria de Abreu JR. Progression of retinopathy and alteration of the blood–retinal barrier in patients with type 2 diabetes: A seven-year prospective follow-up study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1998;236:264–8. doi: 10.1007/s004170050075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fong DS, Segal PP, Myers F, Ferris FL, Hubbard LD, Davis MD. Subretinal fibrosis in diabetic macular edema. ETDRS report 23. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Ophthalmol. 1997;115:873–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160043006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mavrikakis E, Lam WC, Khan BU. Macular edema, diabetic. [Last accessed on 2010 Mar 5]. Available from: http://www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/1224224-overview .

- 25.Lopes de Faria JM, Jalkh AE, Trempe CL, McMeel JW. Diabetic macular edema: Risk factors and concomitants. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999;77:170–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henderson BA, Kim JY, Ament CS, Ferrufino-Ponce ZK, Grabowska A, Cremers SL. Clinical pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Risk factors for development and duration after treatment. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:1550–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ozaki H, Hayashi H, Vinores SA, Moromizato Y, Campochiaro PA, Oshima K. Intravitreal sustained release of VEGF causes retinal neovascularization in rabbits and breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier in rabbits and primates. Exp Eye Res. 1997;64:505–17. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derevjanik NL, Vinores SA, Xiao WH, Mori K, Turon T, Hudish T, et al. Quantitative assessment of the integrity of the blood-retinal barrier in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2462–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kendall C, Wooltorton E. Rosiglitazone (Avandia) and macular edema. CMAJ. 2006;174:623. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Nowotny W. Bevacizumab (Avastin), a humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody for cancer therapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:328–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Genentech. Avastin (Bevacizumab) [Last accessed on 2010 Feb 25]. Available from: http://www.gene.com/gene/products/information/oncology/avastin .

- 32.Presta LG, Chen H, O′Connor SJ, Chisholm V, Meng YG, Krummen L, et al. Humanization of an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody for the therapy of solid tumors and other disorders. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4593–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurwitz HI, Fehrenbacher L, Hainsworth JD, Heim W, Berlin J, Holmgren E, et al. Bevacizumab plus irnotecan, fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang JC, Harworth L, Sherry RM, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for mewztastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:427–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Food and drug administration (FDA) US. U.S. BL 125085/168 Amendment: Bevacizumab Genentech, Inc. (Renal Cell Carcinoma): Final draft. [Last accessed on 2010 Feb 25]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfmfuseaction=Search.Label_ApprovalHistory#apphist .

- 36.Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (27th Feb, 2010) Bevacizumab. [Last accessed on 2010 Mar 01]. Available from: http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bevacizumab .

- 37.Hou J, Tao Y, Jiang YR, Li XX, Gao L. Intravitreal bevacizumab versus triamcinolone acetonide for macular edema due to branch retinal vein occlusion: A matched study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:2695–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guthoff R, Meigen T, Henne Mann K, Schrader W. Comparison of bevacizumab and triamcinolone for treatment of macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion – a matched-Pairs analysis. Ophthalmologica. 2010;224:126–32. doi: 10.1159/000235995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yanyali A, Aytug B, Horozoglu F, Nohutcu AF. Bevacizumab (Avastin) for diabetic macular edema in previously vitrectomized eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:124–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mirshahi A, Namavari A, Djalilian A, Moharamzad Y, Chams H. Intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin) for the treatment of cystoid macular edema in behçet disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:59–64. doi: 10.1080/09273940802553295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arevalo JF, Sanchez JG, Wu L, Maia M, Alezzandrini AA, Brito M, et al. Primary intravitreal bevacizumab for diffuse diabetic macular edema: The Pan-American Collaborative Retina Study Group at 24 months. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1488–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lam DS, Lai TY, Lee VY, Chan CK, Liu DT, Mohamed S, et al. Efficacy of 1.25 MG versus 2.5 MG intravitreal bevacizumab for diabetic macular edema: Six-month results of a randomized controlled trial. Retina. 2009;29:292–9. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31819a2d61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyake T, Sawada O, Kakinoki M, Sawada T, Kawamura H, Ogasawara K, et al. Pharmacokinetics of bevacizumab and its effect on vascular endothelial growth. Factor after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab in macaque eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1606–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andriolo RB, Puga ME, Belfort R, Junior, Atallah AN. Bevacizumab for ocular neovasculardiseases: A systematic review. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009;127:84–91. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802009000200006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takamura Y, Kubo E, Akagi Y. Analysis of the effect of intravitreal bevacizumab injection on diabetic macular edema after cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1151–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cordero Coma M, Sobrin L, Onal S, Christen W, Foster CS. Intravitreal bevacizumab for treatment of uveitic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1574–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soheilian M, Ramezani A, Obudi A, Bijanzadeh B, Salehipour M, Yaseri M, et al. Randomized trial of intravitreal bevacizumab alone or combined with triamcinolone versus macular photocoagulation in diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1142–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russo V, Barone A, Conte E, Prascina F, Stella A, Noci ND. Bevacizumab compared with macular laser grid photocoagulation for cystoid macular edema in branch retinal vein occlusion. Retina. 2009;29:511–5. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318195ca65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmadieh H, Ramezani A, Shoeibi N, Bijanzadeh B, Tabatabaei A, Azarmina M, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab with or without triamcinolone for refractory diabetic macular edema; a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:483–9. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0688-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faghihi H, Roohipoor R, Mohammadi SF, Hojat-Jalali K, Mirshahi A, Lashay A, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab versus combined bevacizumab-triamcinolone versus macular laser photocoagulation in diabetic macular edema. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2008;18:941–8. doi: 10.1177/112067210801800614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paccola L, Costa RA, Folgosa MS, Barbosa JC, Scott IU, Jorge R. Intravitreal triamcinolone versus bevacizumab for treatment of refractory diabetic macular oedema (IBEME study) Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:76–80. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.129122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rothova A, Suttorp-van Schulten MS, Treffers WF, Kijlstra A. Causes and frequency of blindness in patients with intraocular inflammatory disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:332–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.4.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taylor HR. LXIII Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture: Eye care: Dollars and sense. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gutiérrez JC, Barquet LA, Caminal JM, Mitjana, Almolda SP, Domènech NP, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) in the treatment of macular edema secondary to retinal vein occlusion. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008;2:787–91. doi: 10.2147/opth.s3798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lanzagorta-Aresti A, Palacios-Pozo E, Menezo Rozalen JL, Navea-Tejerina A. Prevention of vision loss after cataract surgery in diabetic macular edema with intravitreal bevacizumab: A pilot study. Retina. 2009;29:530–5. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31819c6302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cho WB, Oh SB, Moon JW, Kim HC. Panretinal photocoagulation combined with intravitreal bevacizumab in high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Retina. 2009;29:516–22. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31819a5fc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steigerwalt R, Belcaro G, Cesarone MR, Di Renzo A, Grossi MG, Ricci A, et al. Pycnogenol improves microcirculation, retinal edema, and visual acuity in early diabetic retinopathy. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2009;25:537–40. doi: 10.1089/jop.2009.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaiser PK. Prospective evaluation of visual acuity assessment: A comparison of snellen versus ETDRS charts in clinical practice (An AOS Thesis) Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2009;107:311–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Izquierdo NJ, Emanuelli A, Izquierdo J, Garcia M, Carman C, Maria B. Foveal thickness and macular volume in patients with oculocutaneous Albinism. Retina. 2007;27:1227–30. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3180592b48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grover DA, Li T, Chong CC. Intravitreal steroids for macular edema in diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD005656. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005656.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Generation of allocation sequences in randomised trials: Chance, not choice. Lancet. 2002;359:515–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07683-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Edinburgh (UK): Elsevier; 2006. The Lancet Handbook of Essential Concepts in Clinical Research. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.0 (updated February 2008) The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008. [Last accessed on 2010 Mar 3]. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Chapter 8. Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org . [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deeks JJ, Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.0 (updated February 2008) The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008. [Last accessed on 2010 Mar 15]. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. Chapter 9. Available from: http://www.cochrane–handbook.org . [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith TS, Nanji AA, Greenberg PB. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;10:CD007325. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007325.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simha A, Braganza A, Abraham L, Samuel P, Lindsley K. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for neovascular glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD007920. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007920.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goh D, Lim N. Prophylactic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents for the prevention of cystoid macular oedema after cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD006683. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006683.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.0 (updated February 2008) The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008. [Last accessed on 2010 Mar 21]. Cochrane data base. Chapter 16: Special topics in statistics. Available from: http://www.cochranehand-book.Org . [Google Scholar]

- 69.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Cochrane, chapter 9: Analyzing data and undertaking meta analysis. BMJ. Vol. 327. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2003. [Last accessed on 2010 Mar 29]. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses; pp. 557–60. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.0 (updated February 2008) 2008; Available from: http://www.cochrane–handbook.org . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]