Abstract

Nicotine withdrawal is associated with numerous symptoms including impaired hippocampus-dependent learning. Theories of nicotine withdrawal suggest that nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are hypersensitive during withdrawal, which suggests enhanced sensitivity to nicotine challenge. Research indicates that prior exposure to nicotine enhances sensitivity to nicotine challenge, but it is unclear if this is due to prior nicotine exposure or specific to nicotine withdrawal. Therefore, the present experiments examined if prior nicotine exposure or nicotine withdrawal altered the effects of nicotine challenge on hippocampus-dependent learning. C57BL/6J mice were trained and tested in contextual conditioning following saline or nicotine challenge either during (24 hours after cessation) or after (14 days after cessation) a period of nicotine withdrawal symptoms. Nicotine challenge produced a greater enhancement of contextual conditioning relative to control withdrawal state in mice withdrawn from chronic nicotine for 24 hours compared to 14 days and corresponding saline controls. These experiments support the suggestion that during periods of abstinence, smokers may perceive tobacco providing a large boost in cognition.

Keywords: Nicotine, addiction, withdrawal, learning, cognition, hippocampus

In the United States, cigarette smoking results in 443,000 premature deaths per year despite known negative health consequences [1]. For many smokers, avoidance or alleviation of aversive withdrawal symptoms may contribute to continued nicotine use and relapse during abstinence [2]. One such withdrawal symptom is impaired cognitive function, which is reported to occur in a majority of smokers [3]. In fact, working memory deficits during abstinence predicted smoking resumption [4]. Therefore, understanding the neurobiology of nicotine withdrawal-related changes in cognition will aid in developing better therapeutics for maintaining abstinence.

A great deal of information concerning nicotine’s effects on cognition has come from mouse models [5]. In mice, nicotine withdrawal impaired hippocampus-dependent, but not hippocampus-independent, learning while acute nicotine had an enhancing effect [6, 7]. Both the enhancing effect of acute nicotine and the impairing effect of nicotine withdrawal on learning are mediated by hippocampal β2-containing nAChRs, likely the α4β2* nAChR (* indicates other subunits may be incorporated) [8, 9]. The withdrawal-related impairment in hippocampus-dependent learning is hypothesized to be a result of chronic nicotine upregulating hippocampal α4β2* nAChRs [10]. Chronic nicotine upregulates α4β2* nAChRs in the hippocampus, and this upregulation persists for extended periods of time after cessation of nicotine exposure [10, 11]. In addition to upregulation, chronic nicotine also desensitizes nAChRs [12]. During periods of withdrawal, desensitized nAChRs may regain function while remaining upregulated. The recovery of nAChR function during withdrawal coupled with continued upregulation may contribute to a hypersensitive nAChR system. Indeed, as previously hypothesized [13], because of the increased number of nAChRs that are responsive during withdrawal, some cholinergic systems may become hyperexcitable, which could alter normal function of the hippocampus leading to impaired learning [10].

A hypersensitive nAChR system may produce enhanced sensitivity to nicotine during withdrawal. In support, repeated nicotine exposure produces sensitized locomotor responses [14, 15] and increased neurotransmitter release [15, 16] in response to challenge doses of nicotine. However, these studies utilized repeated injection schedules, which may result in periods of activation, desensitization, and resensitization of nAChRs rather than chronic, continuous nicotine exposure that results in a near complete saturation and desensitization of nAChRs. As nAChR desensitization is suggested to be critically involved in nicotine withdrawal [17], it is unclear if the sensitized responses to nicotine were due to prior nicotine exposure or nicotine withdrawal [14–16]. In addition, none of these studies examined the effects of nicotine on hippocampus-dependent learning. To this end, the present experiments examined if nicotine withdrawal or prior nicotine exposure produces enhanced sensitivity to the effects of nicotine challenge on hippocampus-dependent learning.

Male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) 8–12 weeks at pump implantation were housed 1–4 per cage with ad libitum access to food and water. A 12-hour light/dark cycle was maintained from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM with all experiments conducted during the light cycle. The Temple University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experimental procedures.

Mice were implanted with minipumps (Alzet, Model 1002, Durect Co, Cupertino, CA) that delivered chronic saline or nicotine (6.3 mg/kg/d, freebase weight, s.c.) for 12 days. This dose and route of administration was chosen because it produces plasma nicotine levels in the range observed in smokers [6]. In addition, because of the fast half-life of nicotine in the mouse, minipumps produce similar steady state receptor occupancy as in smokers [18]. In all experiments, minipumps were removed 12 days after implantation to induce spontaneous withdrawal. Surgery was performed under sterile conditions with 5% isoflurane anesthetic.

Nicotine hydrogen tartrate salt (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in 0.9% saline was administered i.p. 2–4 min prior to training and testing of contextual conditioning. Doses were saline, 0.022, 0.045, 0.09, 0.18, or 0.36 mg/kg nicotine (freebase weight, based on previous work [7]).

Training and testing of contextual conditioning was performed in four identical clear Plexiglas chambers housed in sound attenuating boxes; as described elsewhere [19]. Freezing, defined as the absence of all movement except respiration, was sampled for 1 s every 10 s and served as a measure of learning. During training, mice were placed in the chambers and baseline freezing was recorded during the first 120 s of the session. At 148 s, mice were presented with a 2 s, 0.57 mA footshock. At 298 s, an additional 2 s footshock was presented. The mice remained in the chambers for 30 s after the second shock presentation. Approximately 24 hours later, testing of contextual conditioning occurred in the training context in the absence of the footshock and freezing was scored for 5 min.

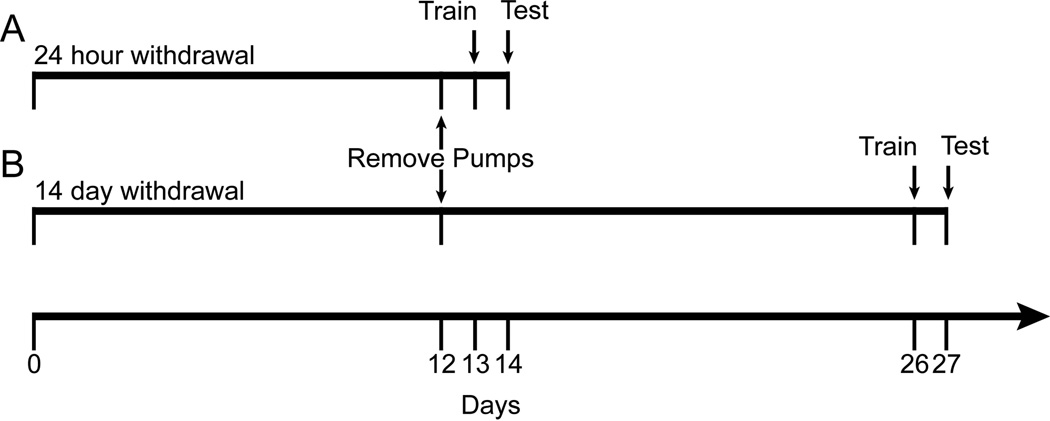

Two experiments were performed that are depicted in Figure 1. Experiment 1 (Figure 1A) examined the effects of saline or nicotine challenge on learning in mice undergoing nicotine withdrawal symptoms. On day 12 of treatment, minipumps were removed from all mice to induce spontaneous withdrawal. Approximately 24 hours later (day 13), mice were randomly assigned to saline or nicotine challenge groups and then were trained in contextual conditioning following injections of saline (withdrawal from chronic saline [WCS] n = 15; withdrawal from chronic nicotine [WCN] n = 14), 0.022 mg/kg (WCS n = 13; WCN n = 13), 0.045 mg/kg (WCS n = 13; WCN n = 13), 0.09 mg/kg (WCS n = 13; WCN n = 16), 0.18 mg/kg (WCS n = 14; WCN = 13), or 0.36 mg/kg (WCS n = 11; WCN n = 10) nicotine challenge. On day 14, mice were injected again with their respective treatment and tested for contextual conditioning. Training day was chosen as the reference day because previous work showed that 24 hours of withdrawal impaired contextual learning [6], but not recall [20]. Experiment 2 (Figure 1B) examined the effects of saline or nicotine challenge on learning in mice previously exposed to chronic nicotine treatment. On day 12, minipumps were removed from all mice. On day 26, mice were randomly assigned to saline or nicotine challenge groups and then were trained in contextual conditioning following injections of saline (WCS n = 14; WCN n = 14), 0.022 mg/kg (WCS n = 13; WCN n = 12). 0.045 mg/kg (WCS n = 16; WCN n = 13), 0.09 mg/kg (WCS n = 12; WCN n = 15), 0.18 mg/kg (WCS n = 12; WCN n = 13) or 0.36 mg/kg (WCS n = 11; WCN n = 13) nicotine challenge. On day 27, mice were injected again with their respective treatments and tested for contextual conditioning. The 14 day time point was chosen because withdrawal-related changes in contextual conditioning were no longer present at that point [10].

Figure 1.

Timeline of the experimental procedures. (A) Experiment 1: minipumps were implanted on day 0 and removed on day 12. Training and testing occurred on days 13 and 14, respectively. (B) Experiment 2: minipumps were implanted on day 0 and removed on day 12. Training and testing occurred on days 26 and 27, respectively.

To compare contextual freezing from testing day across each experiment, freezing data were converted to percent change from control then analyzed using a three-way ANOVA (time point [24 hours, 14 days] × withdrawal [WCS, WCN] ×nicotine challenge dose [0.022, 0.045, 0.09, 0.18, 0.36 mg/kg]). Percent change from control was calculated and defined as: percent change from control = [(Fi – Fc)/( Fc)] × 100, where Fi = mean freezing of individual nicotine challenge doses (0.022 – 0.36 mg/kg) and Fc = mean group freezing of respective controls (either WCS or WCN with saline challenge within each time point). A significant ANOVA was followed by Bonferroni corrected planned contrasts and Tukey's or Games-Howell post-hoc tests. Control mice in each condition exhibited no baseline freezing on training day, therefore percent change from control for baseline freezing could not be calculated. Thus, data were reverted into raw values to analyze baseline freezing as well as the withdrawal × challenge interaction from testing day within each time point with two-way ANOVAs. Significant ANOVAs were followed by Tukey’s or Games-Howell post-hoc tests. Animals 2.5 standard deviations from the mean were excluded as outliers (9 animals).

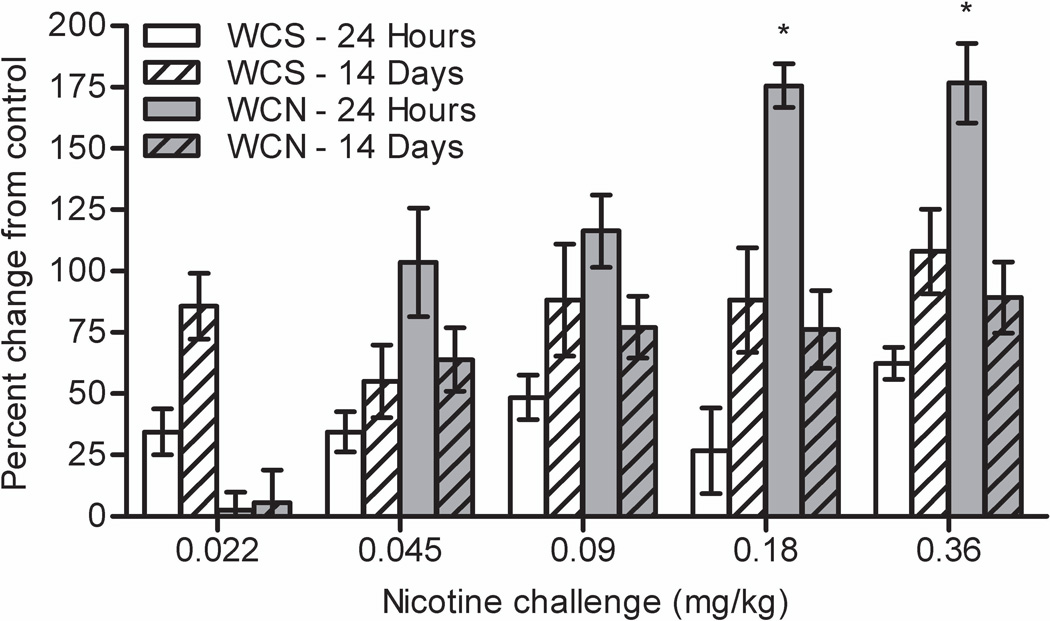

A three-way ANOVA on percent change from control revealed a significant time point × withdrawal × nicotine challenge interaction, F(4, 239) = 2.680, p = 0.032 (Figure 2). Bonferroni corrected planned contrasts revealed that 24 hour WCS mice had a smaller percent change from control than 14 day WCS mice (p < 0.001). This trend was reversed in WCN mice whereby 24 hour WCN mice had a greater percent change from control than 14 day WCN mice (p < 0.001). Overall, 24 hour WCN mice showed a greater nicotine challenge-induced percent change from control than all other withdrawal groups (p < 0.001). Bonferroni corrected planned contrasts also revealed a significant time point × withdrawal interaction within 0.18 and 0.36 mg/kg nicotine challenge (ps < 0.05). Post-hoc tests revealed that 24 hour WCN mice that received 0.18 or 0.36 mg/kg nicotine challenge had a greater percent change from control than mice in all other groups (ps < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Freezing data from both experiments for nicotine challenge treatment converted to percent change from control. The greatest relative enhancement of learning by nicotine challenge occurred in mice withdrawn from chronic nicotine for 24 hours. WCS = withdrawal from chronic saline. WCN = withdrawal from chronic nicotine. Error bars represent ± SEM. (*) indicates p < 0.05 compared to withdrawal groups within the same challenge dose.

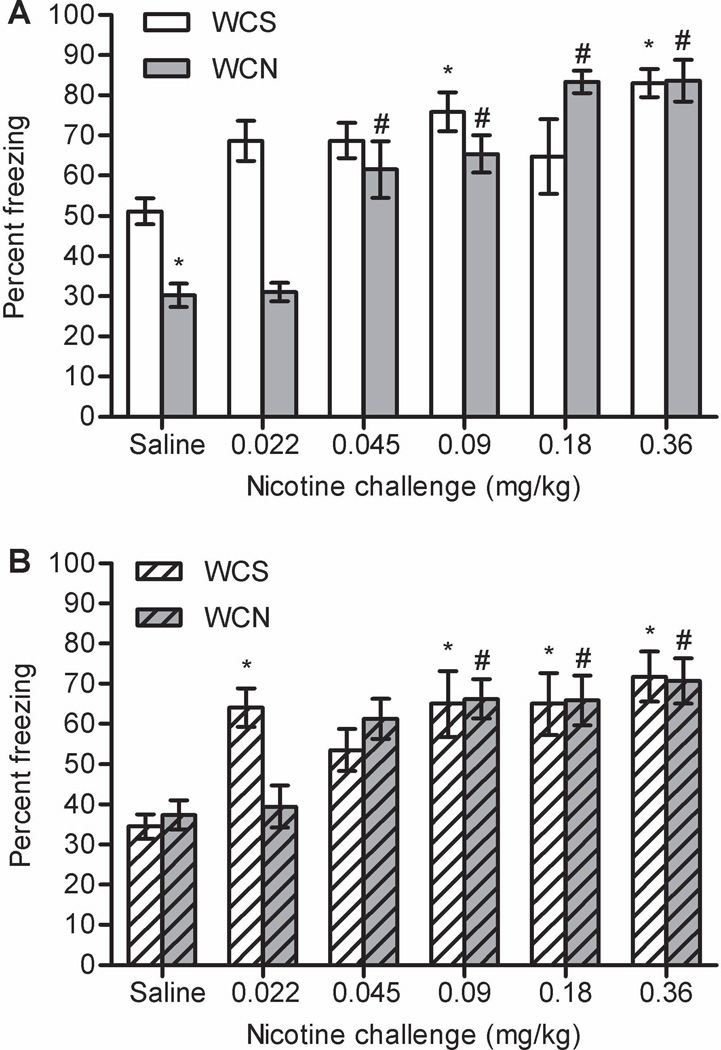

A two-way ANOVA on raw values of baseline freezing at the 24 hour time point revealed a significant main effect of challenge dose, F(5, 146) = 10.116, p < 0.001 (data not shown). Post-hoc tests revealed that mice administered 0.36 mg/kg nicotine challenge froze more than all groups except 0.18 mg/kg nicotine challenge (ps < 0.05). Two-way ANOVA on raw values of contextual freezing from testing day revealed a significant withdrawal × challenge interaction, F(5, 146) = 7.772, p < 0.001 (Figure 3A). Post-hoc tests revealed that WCS mice administered 0.09 and 0.36 mg/kg nicotine challenge froze more to the context than WCS + saline mice (ps < 0.05). WCN + saline mice froze less to the context than the WCS + saline group (p < 0.05), indicating that nicotine withdrawal impaired contextual conditioning. Post-hoc tests revealed that WCN mice administered 0.045, 0.09, 0.18, and 0.36 mg/kg nicotine challenge froze more to the context than WCN + saline mice (ps < 0.05).

Figure 3.

The effects of nicotine challenge on contextual conditioning either (A) 24 hours (experiment 1) or (B) 14 days (experiment 2) after 12 days of chronic nicotine treatment. Nicotine challenge enhanced learning in animals withdrawn from chronic saline and chronic nicotine at both time points. WCS = withdrawal from chronic saline. WCN = withdrawal from chronic nicotine. Error bars represent ± SEM. (*) indicates p < 0.05 compared to WCS + saline mice within each time point. (#) indicates p < 0.05 compared to WCN + saline mice within each time point.

At 14 days, a two-way ANOVA on raw values of baseline freezing revealed a significant main effect of challenge dose, F(5, 146) = 8.386, p < 0.001 (data not shown). Post-hoc tests revealed that mice administered 0.36 mg/kg nicotine challenge froze more than all other groups (ps < 0.05). A two-way ANOVA on raw values of contextual freezing from testing day revealed a significant main effect of challenge dose, F(5, 146) = 11.643, p < 0.001, but no main effect of withdrawal (p > 0.05); the withdrawal × challenge interaction approached significance, F(5, 146) = 2.241, p = 0.053 (Figure 3B). Post-hoc tests revealed that WCS mice administered 0.022, 0.09, 0.18, and 0.36 mg/kg nicotine challenge froze more to the context than WCS + saline mice (ps < 0.05). For the WCN group, mice administered 0.09, 0.18, and 0.36 mg/kg nicotine challenge froze more to the context than WCN + saline mice (ps < 0.05). There were no significant differences between the WCS + saline and WCN + saline groups (p > 0.05).

The present study shows that during nicotine withdrawal, nicotine challenge produced a relatively large enhancement of learning; this could be due to the nAChR system being hypersensitive during nicotine withdrawal, although this was not directly tested. Much like previous work [7], nicotine challenge enhanced contextual conditioning across a wide range of doses in all groups. In addition, withdrawal from chronic nicotine treatment impaired contextual conditioning after 24 hours but not 14 days, in line with previous research [6, 10]. However, because mice withdrawn from chronic nicotine for 24 hours that received saline challenge had impaired learning compared to other groups, data were converted to percent change from control to examine the relative change in freezing with nicotine challenge across all groups. Nicotine challenged administered during 24 hours of nicotine withdrawal produced a relatively large increase in freezing compared to other groups. These results are similar to previous research that found nicotine challenge produced a greater relative change in dopamine response in the nucleus accumbens in nicotine- versus saline-withdrawn mice [21]. This suggests that during abstinence, smokers that relapse might perceive a large gain in cognitive function, which could be misinterpreted as a beneficial effect of smoking. In support, studies that report cognitive enhancing effects of nicotine examined smokers during periods of abstinence [22].

It is possible that nicotine administration affected shock sensitivity, leading to changes in freezing levels across groups. However, previous research found that while nicotine withdrawal did not affect fear conditioning to a tone, context conditioning was disrupted, suggesting the impairing effect of nicotine withdrawal was specific to contextual learning rather than due to shock sensitivity [6]. Also, neither prior chronic nicotine exposure nor acute nicotine administration affected shock sensitivity [23, 24]. Therefore, it is unlikely that differences in shock sensitivity contributed to the present results.

Saline-withdrawn mice that received saline challenge at the 14 day time point had lower levels of freezing compared to saline-withdrawn mice that received saline challenge at the 24 hour time point, while nicotine-withdrawn mice at both time points displayed similar levels of freezing. Thus, an alternative interpretation to the claim that nicotine withdrawal impaired contextual learning is that post-surgical procedures facilitated contextual learning, which was blocked by nicotine exposure. However, this interpretation seems unlikely given that nicotine withdrawal-deficits in contextual conditioning can be precipitated by administration of a nAChR antagonist on training day, in the absence of any surgical procedures [25].

The reason for the greater net change in learning with nicotine challenge during withdrawal is unknown. One possibility is that the mice withdrawn from nicotine for 24 hours showed a lower level of learning and as such there is a greater chance for enhancement to be observed. However, nicotine challenge did not enhance learning in groups treated with chronic saline to 100%, suggesting that further enhancement is possible in these groups. Another possibility is that in the nicotine withdrawal group a greater pool of nAChRs is available. Because chronic nicotine upregulates and desensitizes β2-containing nAChRs [12], desensitized receptors may regain function while upregulation persists when nicotine is removed. This could result in an increased density of functional receptors, which may produce a greater net effect of nicotine. Though, 0.022 mg/kg nicotine challenge did not enhance contextual conditioning in nicotine-withdrawn mice, which may speak against hypersensitive nAChRs during withdrawal. However, research has shown that there are separate pools of nAChRs that are activated by high and low concentrations of nicotine, desensitize at different rates, and resensitize at different rates [26]. In addition, desensitized receptors, which bind nicotine with a higher affinity than fully functional receptors, might act as traps for low concentrations of nicotine, preventing nicotine from binding to fully functional receptors [27]. Thus, it is possible that lower concentrations of nicotine are acting at a separate pool or are ineffective because the nicotine is trapped by desensitized receptors while higher concentrations of nicotine overcome this and activate resensitized receptors. Finally, chronic nicotine could increase metabolism of nicotine, requiring higher doses to produce an effect. However, previous research has shown a relatively weak association between nicotine metabolism and the effects of acute nicotine on learning [28]. Clearly, further testing is required to determine if hypersensitivity of nAChRs during withdrawal contribute to the effects of nicotine challenge on learning.

The enhancing effect of nicotine challenge on hippocampus-dependent learning could facilitate the formation of maladaptive drug-context associations, such that re-exposure to these drug-paired contexts could elicit cravings and precipitate relapse. This suggests that smokers who relapse during periods of nicotine withdrawal may be at a greater risk for forming new maladaptive nicotine-context associations than naïve smokers. It then stands to reason that pharmacological agents that dampen nAChR sensitivity or keep nAChRs desensitized, while not inducing upregulation or activation, may serve as effective treatments for nicotine withdrawal-related impairments in cognitive function during the early stages of abstinence.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge grant support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, DA024787, DA017949, TJG). DSW was supported by a NIDA diversity supplement (DA024787-01A1S1).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.CDC. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report — United States, 2011. MMWR. 2011;60:109–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenny PJ, Markou A. Neurobiology of the nicotine withdrawal syndrome. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:531–549. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward MM, Swan GE, Jack LM. Self-reported abstinence effects in the first month after smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 2001;26:311–327. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson F, Jepson C, Loughead J, Perkins K, Strasser AA, Siegel S, et al. Working memory deficits predict short-term smoking resumption following brief abstinence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;106:61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenney JW, Gould TJ. Modulation of hippocampus-dependent learning and synaptic plasticity by nicotine. Mol Neurobiol. 2008;38:101–121. doi: 10.1007/s12035-008-8037-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis JA, James JR, Siegel SJ, Gould TJ. Withdrawal from chronic nicotine administration impairs contextual fear conditioning in C57BL/6 mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8708–8713. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2853-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gould TJ, Higgins JS. Nicotine enhances contextual fear conditioning in C57BL/6J mice at 1 and 7 days post-training. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2003;80:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7427(03)00057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis JA, Gould TJ. Hippocampal nAChRs mediate nicotine withdrawal-related learning deficits. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19:551–561. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis JA, Kenney JW, Gould TJ. Hippocampal alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor involvement in the enhancing effect of acute nicotine on contextual fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10870–10877. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3242-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gould TJ, Portugal GS, André JM, Tadman MP, Marks MJ, Kenney JW, et al. The duration of nicotine withdrawal-associated deficits in contextual fear conditioning parallels changes in hippocampal high affinity nicotinic acetylcholine receptor upregulation. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:2118–2125. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks MJ, Stitzel JA, Collins AC. Time course study of the effects of chronic nicotine infusion on drug response and brain receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985;235:619–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gentry CL, Lukas RJ. Regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor numbers and function by chronic nicotine exposure. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2002;1:359–385. doi: 10.2174/1568007023339184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dani JA, Heinemann S. Molecular and cellular aspects of nicotine abuse. Neuron. 1996;16:905–908. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domino EF. Nicotine induced behavioral locomotor sensitization. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Bol Psychiatry. 2001;25:59–71. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(00)00148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benwell ME, Balfour DJ. The effects of acute and repeated nicotine treatment on nucleus accumbens dopamine and locomotor activity. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;105:849–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb09067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnold HM, Nelson CL, Sarter M, Bruno JP. Sensitization of cortical acetylcholine release by repeated administration of nicotine in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2003;165:346–358. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benowitz NL. Neurobiology of nicotine addiction: implications for smoking cessation treatment. Am J Med. 2008;121:S3–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matta SG, Balfour DJ, Benowitz NL, Boyd RT, Buccafusco JJ, Caggiula AR, et al. Guidelines on nicotine dose selection for in vivo research. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190:269–319. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenney JW, Florian C, Portugal GS, Abel T, Gould TJ. Involvement of hippocampal jun-N terminal kinase pathway in the enhancement of learning and memory by nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:483–492. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portugal GS, Gould TJ. Nicotine withdrawal disrupts new contextual learning. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;92:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Dong Y, Doyon WM, Dani JA. Withdrawal from chronic nicotine exposure alters dopamine signaling dynamics in the nucleus accumbens. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;71:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell SL, Taylor RC, Singleton EG, Henningfield JE, Heishman SJ. Smoking after nicotine deprivation enhances cognitive performance and decreases tobacco craving in drug abusers. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1:45–52. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian S, Gao J, Han L, Fu J, Li C, Li Z. Prior chronic nicotine impairs cued fear extinction but enhances contextual fear conditioning in rats. Neuroscience. 2008;153:935–943. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gulick D, Gould TJ. The hippocampus and cingulate cortex differentially mediate the effects of nicotine on learning versus on ethanol-induced learning deficits through different effects at nicotinic receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2167–2179. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Portugal GS, Kenney JW, Gould TJ. Beta2 subunit containing acetylcholine receptors mediate nicotine withdrawal deficits in the acquisition of contextual fear conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson ME, Kuryatov A, Choi CH, Zhou Y, Lindstrom J. Alternate stoichiometries of alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:332–341. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giniatullin R, Nistri A, Yakel JL. Desensitization of nicotinic ACh receptors: shaping cholinergic signaling. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Portugal GS, Wilkinson DS, Turner JR, Blendy JA, Gould TJ. Developmental effects of acute, chronic, and withdrawal from chronic nicotine on fear conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2012;97:482–494. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]