Abstract

We have identified tens of thousands of short extrachromosomal circular DNAs (microDNA) in mouse tissues as well as mouse and human cell lines. These microDNAs are 200–400 bp long, derived from unique non-repetitive sequence and are enriched in the 5' untranslated regions of genes, exons and CpG islands. Chromosomal loci that are enriched sources of microDNA in adult brain are somatically mosaic for micro-deletions that appear to arise from the excision of microDNAs. Germline microdeletions identified by the "Thousand Genomes" project may also arise from the excision of microDNAs in the germline lineage. We have thus identified a new DNA entity in mammalian cells and provide evidence that their generation leaves behind deletions in different genomic loci.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variations are known sources of genetic variation between individuals (1–5), but there is also great interest in variations that arise during generation of somatic tissues like the mammalian brain, leading to genetic mosaicism between somatic cells. To identify sites of intramolecular homologous recombination during brain development, we searched for extrachromosomal circular DNA (eccDNA) derived from excised chromosomal regions in normal mouse embryonic brains.

We purified eccDNA from nuclei of embryonic day 13.5 (ED13.5) mouse brain, and removed linear DNA by digestion with an ATP-dependent exonuclease (6) (Fig. S1, Table S1 and SOM Methods). Multiple displacement amplification (MDA) with random primers (7, 8) enriched circular DNA by rolling circle amplification. The linear products of MDA were sheared to 500 bp fragments, cloned into a plasmid and clones sequenced. Out of 93 clones, 73 contained direct repeats of several hundred base-pairs (Fig. S2), as would be expected from rolling circle amplification of circles that are a few hundred bp long. Only one copy of the repeat sequence was present in the mouse genome (Fig. S2, S3), indicating that the direct repeats were derived from unique non-repetitive DNA in the genome and could have been generated by rolling circle amplification of a circularized form of genomic DNA.

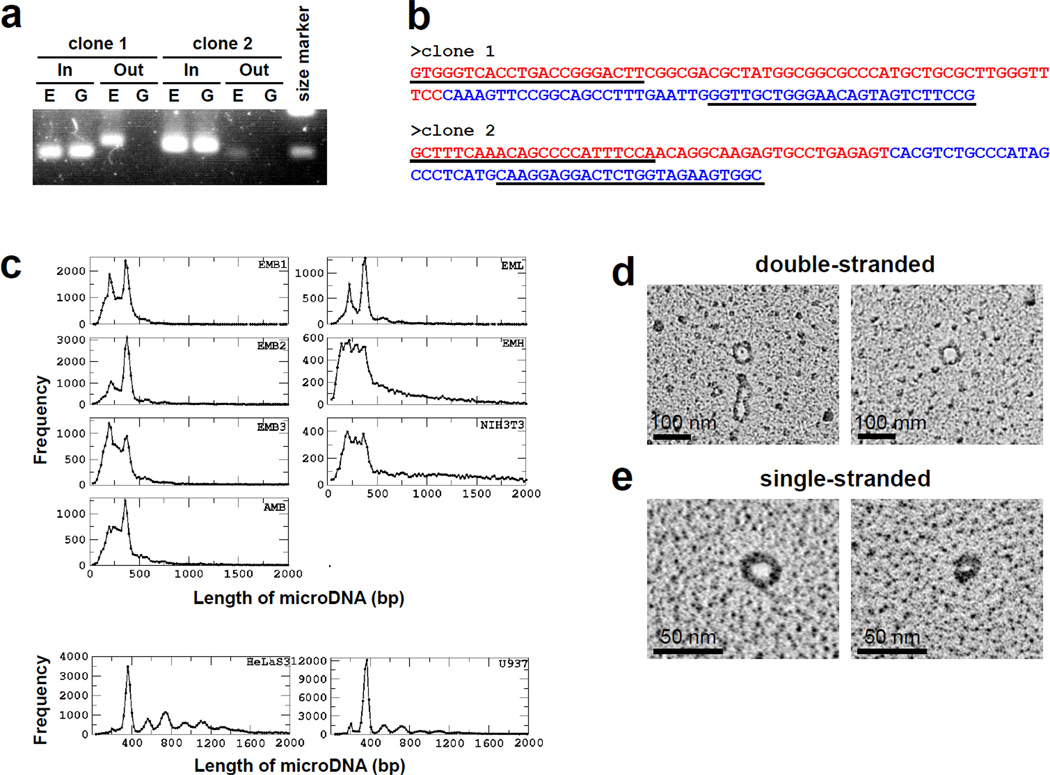

Three sequences that appeared >2 times in the 73 clones were chosen to confirm the circular nature of the extrachromosomal DNA before any MDA. Outward-directed primers yielded PCR products from 10% of total extrachromosomal DNA (without any MDA), but not from linear genomic DNA for two out of the three sequences (Fig. 1a). The PCR products from outward-directed primers had the same junctions as seen between repeats in the MDA products of the extrachromosomal DNA (Fig. 1b). These results are consistent with the circularization of linear genomic DNA to produce extrachromosomal circular DNA.

Fig. 1. Tiny circular DNA are detected in the extrachromosomal DNA fraction.

a. Outward-directed PCR primers (Out) amplified DNA fragments from extrachromosomal DNA (E), but not from genomic DNA (G). DNA was amplified by inward-directed PCR primers (In) from both (E) and (G). b. Sequencing of fragments amplified by Out primers on extrachromosomal fraction. Underlined sequences indicate primers. Junctions between red and blue sequences were the same as that observed in clones in Fig. S2. c. Length distribution of microDNAs from various tissues and cell lines. The library abbreviations are explained in SOM. d. EM of double-stranded microDNA examined by the cytochrome c drop spreading method (16) (50 nm = 150 bp). e. EM of single-stranded microDNA after binding with the T4 gene 32 single stranded DNA binding protein (17).

To determine the number, size, nature and source of these short eccDNA, we isolated eccDNA from ED13.5 mouse brain, heart and liver, adult mouse brain, mouse (NIH3T3), and human (HelaS3 and U937) cell lines (Table S1). Following MDA of the eccDNA, ~500 bp fragments of the amplified DNA were subjected to paired-end sequencing. As a negative control, chromosomal DNA from embryo mouse brain nuclei was treated in an identical manner to the eccDNA fraction. We also examined eccDNA fraction from S.cerevisiae by exactly the same procedure (SOM text). Circular DNAs were identified by two different algorithms that were dependent on the identification of junctional tags created by the circularization (Fig. S4 and SOM Methods). Tens of thousands of unique sequences in the genome were identified as yielding extrachromosomal circular DNA (Table S2) and their total yield was 0.1–0.2 % weight of chromosomal DNA in normal tissue. In contrast, the negative control mouse chromosomal DNA yielded only 114 circles, all arising from contamination by extrachromosomal DNA, because the same circles were abundant in the ecc libraries. No circles were detected in the S. cerevisiae extrachromosomal DNA.

The circular DNA from mouse tissues and cell lines were 80–2000 bp long, though >50% were in the 200–400 bp range with clear peaks in the brain and liver at ~200 and ~400 bp (Fig. 1c). In the two human cancer cell lines, where we identified many more circular DNAs, the length distribution also peaked at 200 and 400 bp but had additional peaks with a periodicity of 150 bp (Fig. 1c). The circular DNAs were uniquely mapped to the genome and were not derived from repetitive sequences. These DNAs were therefore different from previously reported eccDNAs that were a few hundred to millions of bases long and derived from chromosomal repetitive sequences, intermediates of mobile elements or viral genomes (9, 10). Based on their small size and derivation from unique genomic sequence we named this family of DNA as microDNA.

To detect the 200–400 base long microDNAs in cells by a fourth method, the eccDNA fraction from mouse brain, after exonuclease digestion but without rolling circle amplification, was directly examined by electron microscopy. Double-stranded microDNA that are several hundred bp long were easily detected (Fig. 1d, Fig. S5a, b). We also found single-stranded microDNA visualized after the treatment of DNA by single-stranded DNA binding protein, gp32 (Fig. 1e, Fig. S5a, b). The double- and single-stranded microDNAs were equivalent in number. More than 98% of the circular DNA from mouse brain was small (<1 kb) (SOM text), making this the dominant population of eccDNA in normal somatic tissue.

Thus PCR with outward directed primers (Fig. 1a, b) or electron microscopy (Fig. 1d, e) on extrachromosomal DNA fraction without MDA confirmed the presence of short circles that were revealed by Sanger sequencing (Fig. S2, S3) or ultrahighthroughput sequencing (Fig. 1c, S4) of MDA products.

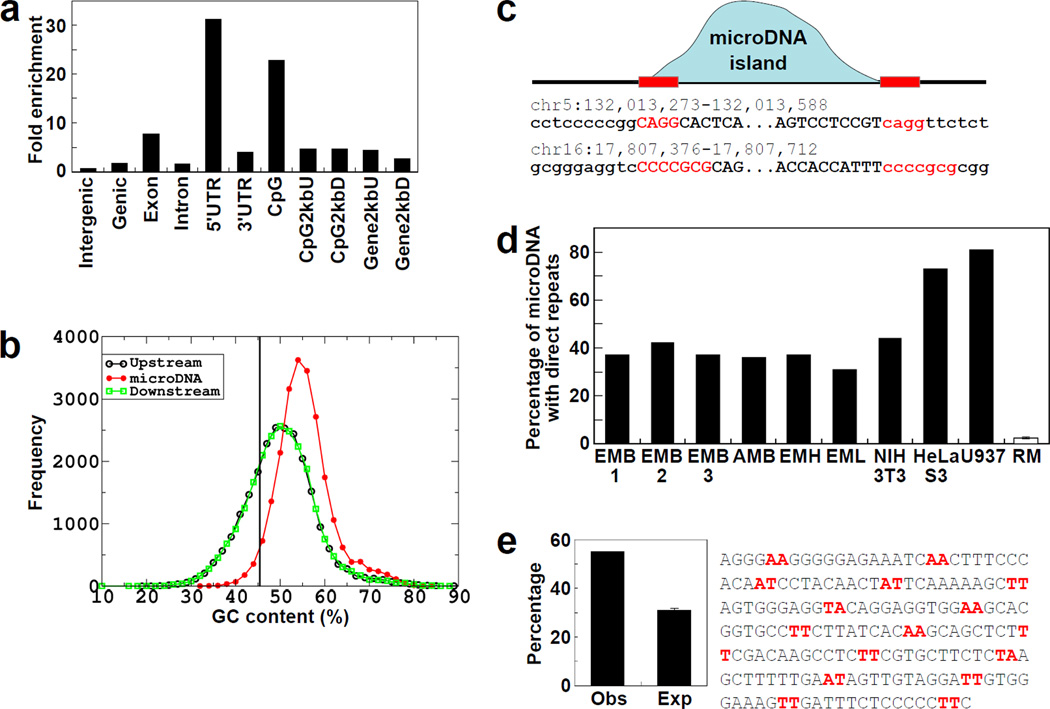

The sources of the microDNAs from the embryo mouse brain (EMB1) were highly enriched in genic regions, especially 5’ regions of genes, exons, and CpG islands (Fig. 2a). A similar trend was also observed in microDNA from other mouse tissues and mouse and human cell lines (Fig. S6). Furthermore, the 55% GC content of microDNAs is higher than the 50% GC content of the immediate upstream or downstream flanking regions and the 45% GC composition of the entire genome (Fig. 2b, Fig. S7 and Fig. S8). The starts and ends of the circles r evealed 2–15 bp direct repeats of micro-homology (Fig. 2c, Fig. S9). In the EMB1 library 37% of the microDNA has this micro-homology, while in the random model (SOM Method) <3% of the shuffled microDNAs had micro-homology of ≥2 bp near the ends (p<0.0001) (Fig. 2d). Direct repeats were similarly present at the ends of the microDNA from all mouse tissues and human cell-lines (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2. Properties of the loci that give rise to microDNAs.

a. Enrichment of microDNAs observed in the indicated genomic region relative to the expected percentage based on random distribution. b. Distribution of GC composition in microDNAs in the EMB1 library and their up- and down-stream regions (of same length as microDNA). Vertical line: the genomic average GC content. c. Presence of micro homology near the start and end of a microDNA. "MicroDNA island (blue curve)" is a contiguous stretch of the genome to which the PE-tags map uniquely and correctly. Direct repeats of 2–15 bp (red letters) were observed at the junction of the circle (Upper case) with flanking genomic DNA (Lower case). d. Direct repeats are enriched in different microDNA libraries compared to the random model (RM), generated from the EMB1 sequences. e. Intersection of microDNAs from EMB1 with positioned nucleosome-occupied regions in the mouse liver (13). Obs: observed overlap with nucleosome-occupied DNA. Exp: expected overlap of 1000 randomizations of each microDNA in the library (p<0.0001). A similar enrichment is seen with other microDNA libraries (Fig. S10).

The lengths of microDNAs from cancer cell lines show a pronounced periodicity of 150 bp, (Fig. 1c) consistent with the possibility that nucleosome wrapping of DNA may contribute to microDNA generation. In addition, though microDNAs are rich in GC content, AA/AT/TT dinucleotides were found along the length of many circles with a periodicity of 9–11 bp (example in Fig. 2e). GC richness periodically punctuated by AA/AT/TT dinucleotides is a feature of sequences preferentially assembled into nucleosomes (11, 12). Around 50–60% of microDNAs in the different libraries overlapped by ≥15 bases with 25-mer tags marking the locations of positioned nucleosomes determined in the mouse liver (13) (Fig. 2e & Fig. S10) (p< 0.001 in “t” test from random distribution).

The features of these microDNAs are completely different from the sequences obtained from chromosomal DNA, suggesting that the specific characteristics of microDNA are not an artifact of random sampling of cellular DNA by highthroughput sequencing (Fig. S11a–c and SOM Text).

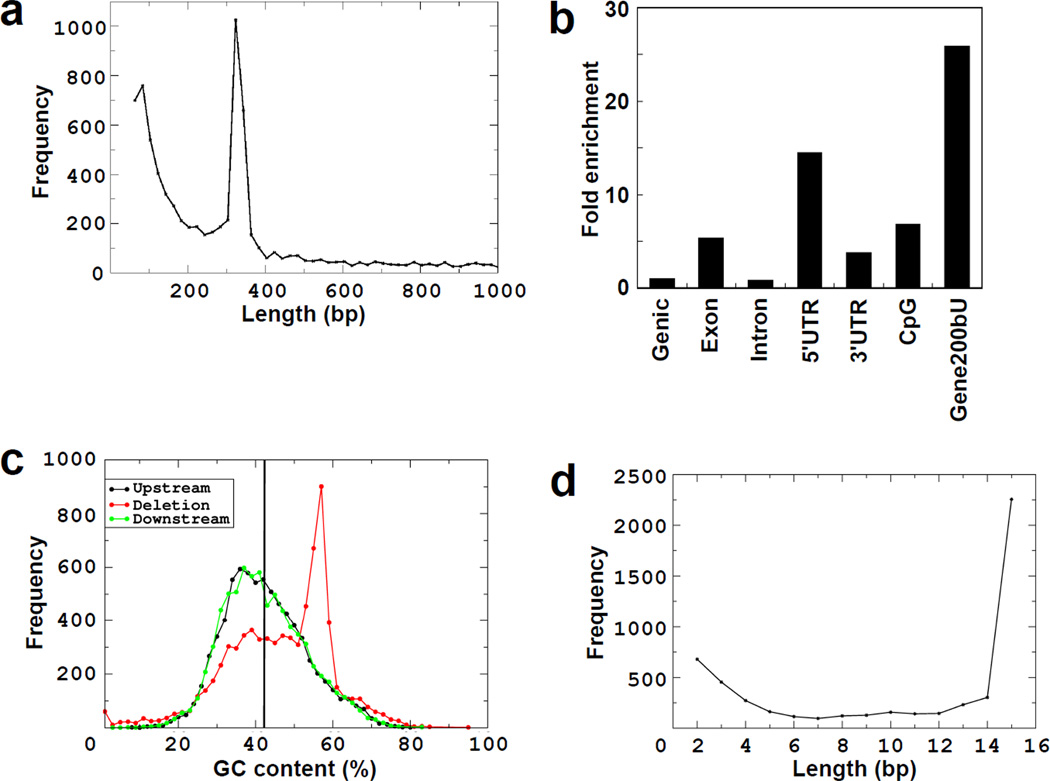

Cells that release a double-stranded circular DNA may be expected to suffer a microdeletion in the source genomic locus. A search for such microdeletions is complicated by the fact that different cells are likely to yield different microDNAs, so that a tissue will be mosaic for microdeletions. We therefore selected two genomic loci that yielded microDNAs in multiple brain libraries. One was 20 kb at the 5' end of the KCNK3 gene in chromosome 5 (30,890,697–30,910,805, NCBI37/mm9) enriched by PCR (Fig. 4b), and another was 160 kb on chromosome 10 (80,213,587–80,372,454, NCBI37/mm9) enriched by Anchored ChromPET (14). The strategy for finding microdeletions in the selected loci is given in Fig. 3a and the SOM Methods. A total of thirty deletions were detected (23 from the KCNK3 locus and 7 from the chromosome 10 locus) (Fig. 3a and S13). Direct repeats were observed at both ends of 25 of the 30 microdeletions (Fig. 3b and S13). The GC composition, length distribution and AA/AT/TT periodicity of the microdeletions were also similar to that observed for the microDNA (Fig. 3c, S12 and S13). The results suggest that microdeletions occur in an average of 1 in 2000 chromosomal DNA molecules (SOM text) at susceptible genomic loci in somatic tissues, giving rise to genetic variability between individual normal somatic cells.

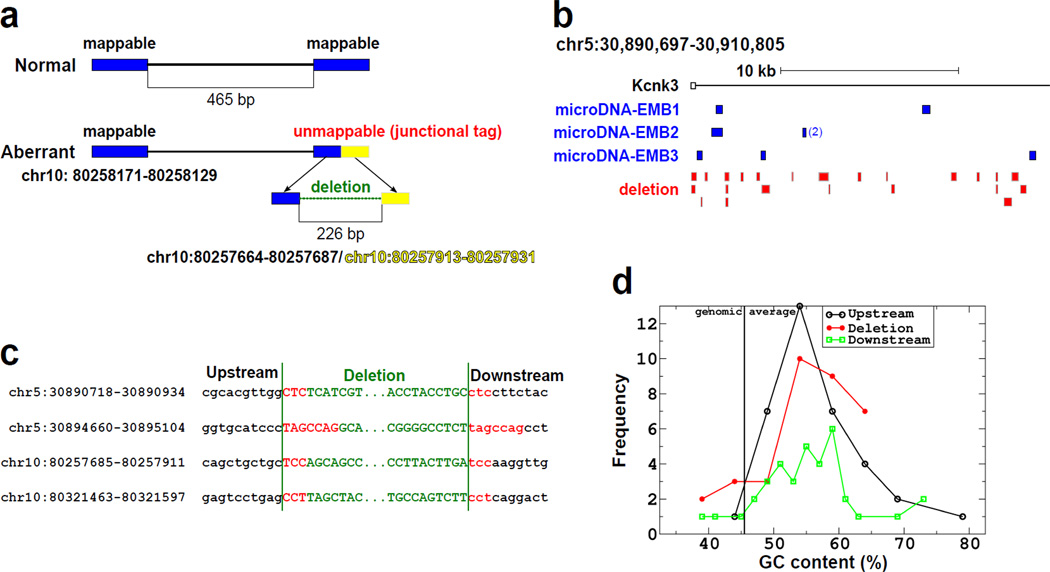

Fig. 4. Germline deletions of <1000 bp in the Thousand Genomes Project have properties similar to microDNAs.

a. Length distribution peaks at 100 bp and 350 bp. b. Deletions in genic areas are enriched in 5'UTRs, exons, CpG islands and regions 200bp upstream from genes. c. GC content of deletion and up-stream and down-stream regions is greater than genomic average. The up-stream and down-stream sequence was of same length as the deletions. d. 70% of the microdeletions had flanking direct repeats. Length distribution of the direct repeats is shown. Direct repeats ≥15 bp are shown at 15 bp.

Fig. 3. Microdeletions in genomic loci known to yield microDNAs.

a. Algorithm for finding microdeletions in genomic DNA. Details in SOM. b. Micro-deletions found in the KCNK3 locus. DNA spanning the indicated locus was amplified from 200,000 copies of 6 month old mouse brain genomic DNA, and paired-end-sequenced. White square is KCNK3 exon1 and solid line is KCNK3 intron1. Blue squares are positions of microDNAs identified in three independent embryonic brain libraries, and red squares are microdeletions found in the genome in this study. c. Direct repeats observed near the junctions of microdeletions. d. GC composition of the microdeletions identified in the two loci. The deleted sequences were rich in GC content compared to the genomic average of 46%.

The widespread occurrence of microDNAs led us to wonder whether microdeletions in germ line sequence could also result from the excision of microDNAs. In fact the germline deletions of <1000 bp reported in the Thousand Genomes project (15) had features similar to that of microDNAs (Fig. 4a–d and SOM Text). Briefly, the germline microdeletions peaked in length at 100 and 350 bp, were enriched in exons, 5'UTRs and CpG islands, were rich in GC content and had a high frequency of short direct repeats flanking the deleted fragments. This close overlap between the nature of the sequences lost in germline microdeletions and the microDNAs reported in this paper suggest that these deletions are also generated by the excision and loss of microDNAs.

Unlike formerly described eccDNA (9, 10), microDNAs are small, map to unique DNA sequence and appear from genes. Very short direct repeats at the starts and ends of microDNAs suggest that fork stalling/template switching during replication/repair or microhomology-mediated repair may produce microDNAs. Circularization of microDNAs could be facilitated by the wrapping of DNA around positioned nucleosomes. The known correspondence of positioned nucleosomes with 5' ends of genes could explain the enrichment of microDNAs from the 5' ends of genes. MicroDNAs could also originate as displaced Okazaki fragments from replication forks collapsed at strongly bound nucleosomes or GC-rich DNA. Single-stranded microDNAs may arise from such ligated Okazaki fragments, from deletion of excess DNA produced by replication slippage or from nuclease digestion of nicked double-stranded circles. However, the microdeletions detected in genomic loci most likely arise from excision of double-stranded circles. The generation of microDNAs and microdeletions may produce a large pool of individual-specific or somatic-clone-specific copy-number variations of small segments of the genome. The genetic mosaicism in somatic tissues may lead to functional differences between cells in a tissue. Finally persistent microDNAs may provide the extrachromosomal genetic "cache" that has been postulated to account for non-Mendelian genetics in plants (18).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01 CA60499 and GM84465 to AD, and GM31819 and ESO13773 to JDG. We thank all members of the Dutta Lab for helpful discussions, and A. Prorock for assistance with DNA sequencing.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

Materials and Methods

SOM Text

Abbreviation

Fig. S1 to S13

Table S1 and S2

References (32 and 41)

Contributor Information

Yoshiyuki Shibata, Email: ys5h@virginia.edu.

Pankaj Kumar, Email: pk7z@virginia.edu.

Ryan Layer, Email: rl6sf@virginia.edu.

Smaranda Willcox, Email: smaranda_willcox@med.unc.edu.

Jeffrey R. Gagan, Email: jrg4r@virginia.edu.

Jack D. Griffith, Email: jdg@med.unc.edu.

Anindya Dutta, Email: ad8q@virginia.edu.

References and notes

- 1.Beckmann JS, Estivill X, Antonarakis SE. Copy number variants and genetic traits: closer to the resolution of phenotypic to genotypic variability. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2007;8:639–646. doi: 10.1038/nrg2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flores M, et al. Recurrent DNA inversion rearrangements in the human genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:6099–6106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701631104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frazer Ka, Murray SS, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Human genetic variation and its contribution to complex traits. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2009;10:241–251. doi: 10.1038/nrg2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR. Structural variation in the human genome and its role in disease. Annual Review of Medicine. 2010;61:437–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-100708-204735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lupski JR. New mutations and intellectual function. Nature Genetics. 2010;42:1036–1038. doi: 10.1038/ng1210-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamagishi H, et al. Purification of small polydisperse circular DNA of eukaryotic cells by use of ATP-dependent deoxyribonuclease. Gene. 1983;26:317–321. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean FB, et al. Comprehensive human genome amplification using multiple displacement amplification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:5261–5266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082089499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lovmar L, Syvänen A-C. Multiple displacement amplification to create a long-lasting source of DNA for genetic studies. Human Mutation. 2006;27:603–614. doi: 10.1002/humu.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maeda T, et al. Somatic DNA recombination yielding circular DNA and deletion of a genomic region in embryonic brain. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;319:1117–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen S, Segal D. Extrachromosomal circular DNA in eukaryotes: possible involvement in the plasticity of tandem repeats. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 2009;124:327–338. doi: 10.1159/000218136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Segal E, et al. A genomic code for nucleosome positioning. Nature. 2006;442:772–778. doi: 10.1038/nature04979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segal E, Widom J. What controls nucleosome positions? Trends in Genetics. 2009;25:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Changolkar LN, et al. Genome-wide distribution of macroH2A1 histone variants in mouse liver chromatin. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2010;30:5473–5483. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00518-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shibata Y, Malhotra A, Dutta A. Detection of DNA fusion junctions for BCR-ABL translocations by Anchored ChromPET. Genome Medicine. 2010;2:70. doi: 10.1186/gm191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mills RE, et al. Mapping copy number variation by population-scale genome sequencing. Nature. 2011;470:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature09708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thresher R, Griffith J. Electron microscopic visualization of DNA and DNA-protein complexes as adjunct to biochemical studies. Methods in Enzymology. 1992;211:481–490. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)11026-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffith JD, Christiansen G. Electron microscope visualization of chromatin and other DNA-protein complexes. Annual Review of Biophysics and Bioengineering. 1978;7:19–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.07.060178.000315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lolle SJ, Victor JL, Young JM, Pruitt RE. Genome-wide non-mendelian inheritance of extra-genomic information in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2005;434:505–509. doi: 10.1038/nature03380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.