Abstract

Objective

To estimate the potential reduction in cardiovascular (CVD) mortality possible by decreasing salt, trans fat and saturated fat consumption, and by increasing fruit and vegetable (F/V) consumption in Irish adults aged 25–84 years for 2010.

Design

Modelling study using the validated IMPACT Food Policy Model across two scenarios. Sensitivity analysis was undertaken. First, a conservative scenario: reductions in dietary salt by 1 g/day, trans fat by 0.5% of energy intake, saturated fat by 1% energy intake and increasing F/V intake by 1 portion/day. Second, a more substantial but politically feasible scenario: reductions in dietary salt by 3 g/day, trans fat by 1% of energy intake, saturated fat by 3% of energy intake and increasing F/V intake by 3 portions/day.

Setting

Republic of Ireland.

Outcomes

Coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke deaths prevented.

Results

The small, conservative changes in food policy could result in approximately 395 fewer cardiovascular deaths per year; approximately 190 (minimum 155, maximum 230) fewer CHD deaths in men, 50 (minimum 40, maximum 60) fewer CHD deaths in women, 95 (minimum 75, maximum 115) fewer stroke deaths in men, and 60 (minimum 45, maximum 70) fewer stroke deaths in women. Approximately 28%, 22%, 23% and 26% of the 395 fewer deaths could be attributable to decreased consumptions in trans fat, saturated fat, dietary salt and to increased F/V consumption, respectively. The 395 fewer deaths represent an overall 10% reduction in CVD mortality. Modelling the more substantial but feasible food policy options, we estimated that CVD mortality could be reduced by up to 1070 deaths/year, representing an overall 26% decline in CVD mortality.

Conclusions

A considerable CVD burden is attributable to the excess consumption of saturated fat, trans fat, salt and insufficient fruit and vegetables. There are significant opportunities for Government and industry to reduce CVD mortality through effective, evidence-based food policies.

Keywords: Modelling, Salt, Saturated Fat, Ireland

Article summary.

Article focus

To estimate the potential reduction in cardiovascular (CVD) mortality (coronary heart disease and stroke) possible by decreasing salt, trans fat and saturated fat consumption, and by increasing fruit and vegetable (F/V) consumption in Irish adults aged 25–84 years for 2010 across two scenarios employing a modelling study design.

First, a conservative scenario: reductions in dietary salt by 1 g/day, trans fat by 0.5% of energy intake, saturated fat by 1% energy intake and increasing F/V intake by 1 portion/day.

Second, a more substantial but politically feasible scenario: reductions in dietary salt by 3 g/day, trans fat by 1% of energy intake, saturated fat by 3% of energy intake and increasing F/V intake by 3 portions/day.

Key messages

Coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality in Ireland fell by more than 50% between 1985 and 2006.

A further 26% overall decline in both CHD and stroke deaths per year could be achieved if more substantial but politically feasible food policy options were adopted in Ireland.

A total of 1070 fewer CHD and stroke deaths per year could occur in Ireland by achieving reductions in current dietary salt by 3 g/day, trans fat by 1% of current energy intake and saturated fat by 3% of current energy intake and increasing fruit and vegetable intake by 3 portions/day.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A previously validated IMPACT food policy model was employed.

Robust sensitivity analyses were performed to account for uncertainties.

Latest population-level estimates were utilised.

Risk factor effects were assumed to be independent, which could be an overestimation.

Lag times were not addressed.

The model assumes a linear dose–response relationship between food components and health outcomes that may not necessarily be true.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease remains the main cause of premature deaths and a major cause of disability in Europe. It is estimated that 80% of premature coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke can be prevented.1 Even small reductions in incidence and mortality will lead to large population health gains and potential reductions in direct and indirect healthcare costs.2 Ireland has seen significant declines in CHD death rates between 1985 and 2000.3 Half of these reduced CHD deaths were attributed to improvements in population risk factors, mainly reductions in smoking, blood pressure and cholesterol levels. In a recent updated modelling study of CHD mortality decline in Ireland between 1985 and 2006, similar trends were observed. However, in the latter study, deteriorating trends in obesity and diabetes prevalence were observed.4 For many population-level interventions, the first step is to quantify the effectiveness of such interventions to make judgements on the allocation of finite health resources. Two recent modelling studies in the UK estimated that approximately 30 000–33 000 premature deaths every year could be averted if UK dietary recommendations were met.5 6 One of the UK dietary recommendations was the goal of 6 g/day salt intake.6

Public health policies to protect and promote population health are necessarily based on the totality of evidence. Poor diet has been consistently linked with increased cardiovascular disease and cancer.1 7 The evidence on salt and blood pressure, for instance, now overwhelmingly supports action to reduce population exposure to this dietary additive.8 There is also evidence that high salt intake directly increases the risk of stroke and heart attack.9 10 Current estimates for dietary saturated fat, salt and fruit or vegetable intake among adults (≥18–84 years of age) in the Republic of Ireland are shown in table 1 together with details of population-level dietary targets as specified in the Irish National Cardiovascular Health Policy (2010–2019).11 Population-level estimates of trans fat intake are not currently available. In general, women have lower intakes of saturated fat and salt and higher intakes of fruits and vegetables. Salt intake in particular is very high among Irish men at 10 g/day in 2007. Meta-analyses of large cohort studies addressing the impact of saturated fat, trans fat, salt and fruit and vegetable intakes on CVD risk are consistent with significant effects on mortality from CHD and stroke.10 12–15 For example, reducing daily salt intake by 5 g would translate into approximately 17% and 23% fewer CHD and stroke deaths in a year, respectively.10 One additional portion of fruit and vegetables a day would reduce CHD and stroke deaths by approximately 4% and 5%, respectively.12 13

Table 1.

Current estimates of fats, salt, fruit and vegetable intake in Ireland for both sexes

| Data source | Nutrient mean (SD) | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLAN (2007) | |||

| Total fat (g/day) | 98 | 86 | |

| SFA (g/day) | 36 | 30 | |

| SFA (% energy intake) | 14 | 12 | |

| Fruit mean portions (SD) | 2.6 (2.4) | 3.1 (2.8) | |

| Vegetables mean portions (SD) | 3.9 (2.6) | 4.6 (3.2) | |

| Salt mean (SD) | 10.3 (5.0) | 7.4 (4.2) | |

| NANS (2008–2010) | |||

| SFA (g/day) | 38.7 (13.1) | 28.9 (9.5) | |

| SFA (% energy intake) | 13.1 (3.2) | 13.5 (3.3) | |

| Fruit and vegetables mean (g/day) | 181 (140) | 197 (152) | |

Irish CVD Policy 2010–2019: population-level dietary targets.11

Reduce to <10% the dietary intake from saturated fatty acids.

Reduce to <2% the dietary energy intake from trans-fatty acids.

Achieve reduction to a target of no greater than 6 g/day of salt for adults by 2019.

Increase by 20% the proportion of adults consuming the recommended five or more daily servings (portions) of fruit and vegetables (from 65% to 78%) by 2014.

NANS, National Adult Nutrition Survey; SFA, saturated fatty acids; SLAN, Survey of Lifestyles, Attitudes and Nutrition.

The aim of this study is to estimate the potential reductions in CHD and stroke mortality achievable by specific and feasible decreases in consumption of saturated fat, trans fat, salt and increases in consumption of fruits and vegetables in the Irish population employing a previously validated CHD epidemiological model, the IMPACT model. Two scenarios will be modelled: a conservative scenario and a substantial but politically feasible scenario.

Methods

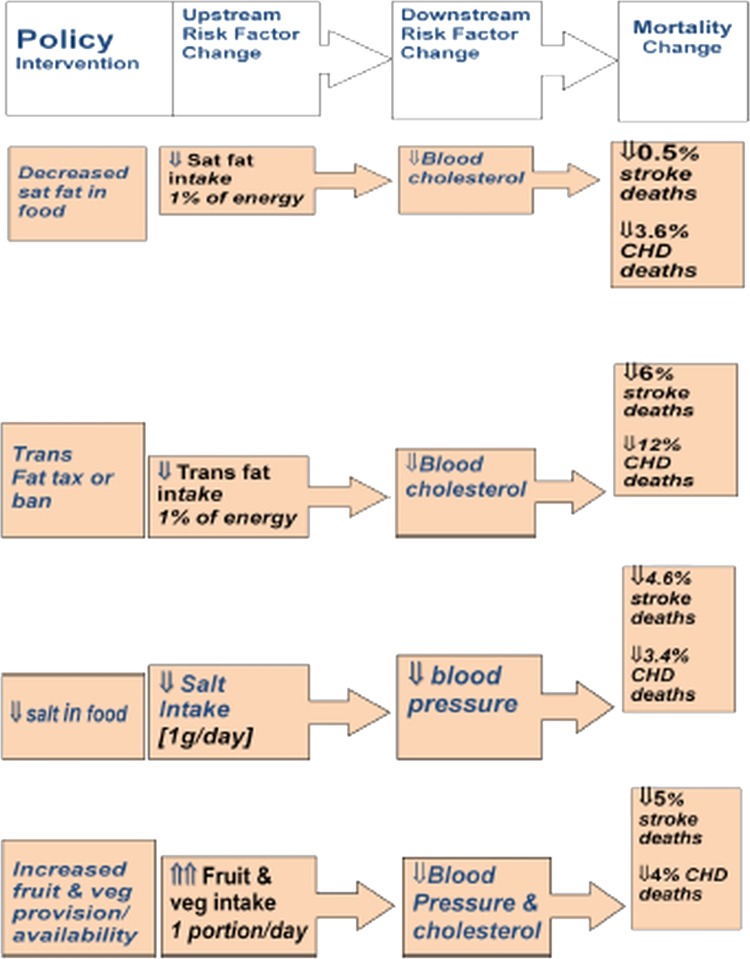

Details of the Irish CHD IMPACT model were published earlier.3 4 In brief, the food policy IMPACT model is an extension and adaptation of the original CHD IMPACT model and is conceptually similar to the IMPACT food model published recently.5 The conceptual framework is based on a theoretical model relating the consumption of foods and nutrients to adverse health outcomes through biological risk factors for ill health (figure 1). Details of each of the specific food policy options and the effect estimates are described in table 2. The effect estimates are drawn from recent relevant meta-analyses of the effects of specific nutrient exposures on CVD risk.10 12–15

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework supporting the Irish food policy IMPACT model.

Table 2.

Food policy scenarios and corresponding effect estimates for modelling fewer cardiovascular mortality estimates in Ireland in 2010

| Effect estimates |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food/nutrient | Modest scenario targets | Feasible scenario targets | CHD (applied to modest targets) | Stroke |

| Saturated fat (% energy intake/day) | ⇓ 1.0 | ⇓ 3.0 | 3.614 | 0.514 |

| Trans fat (% energy intake/day) | ⇓ 0.5 | ⇓ 1.0 | 6.015 | 3.015 |

| Salt intake (g/day) | ⇓ 1 | ⇓ 3 | 3.410 | 4.610 |

| Fruits/vegetables (portions/day) | ⇑ 1 | ⇑ 3 | 4.012 | 5.013 |

CHD, Coronary heart disease.

Data sources

The main outcomes of interest are CHD and stroke deaths in Ireland for the latest calendar year 2010 for which data are currently available. Age-specific and sex-specific aggregate data for both CHD (International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10: 120–125) and stroke (ICD 10: 160–169) deaths were obtained from the Central Statistics Office of Ireland.

In the current model, we used available estimates of the direct association between the four food components and CHD and stroke deaths, similar to the recent UK studies.5 6 Sugars were not included in the model, since the relationship between sugar and CHD, stroke or biological risk factors has not been well established in any recent meta-analysis.

Details of the two scenarios (modest versus feasible) and corresponding effect estimates based on meta-analyses from large cohort studies for each of the food components are shown in table 2.

Model assumptions

Owing to the modelling estimations, the following assumptions were made:

Combined changes in relative risk (RR) for individuals are multiplicative (eg, if consuming one extra portion of fruit and vegetables reduces the risk of CHD death by 10%, and reducing salt intake by 1 g/day reduces the risk of CHD death by 12%, then both of these behaviour changes reduce the risk of CHD death by 1-(1–0.10)×(1–0.12)=20.8%).

Changes between current food component consumption and the expected two scenarios examined will be made by all individuals within the population changing consumption by the same amount.

Finally, reductions in unit change in RR refer to a unit change in food component consumption or proximal risk factors following a dose–response relationship (eg, a change in consumption of fruit and vegetables from 2 to 3 portions a day has the same effect on relative risk as a change in consumption from 8 to 9 portions a day).

Sensitivity analyses

To account for uncertainties around the estimates, a Monte Carlo simulation was conducted. Parameters based on the various meta-analyses incorporated into this modelling study were allowed to vary stochastically. The 95% credible estimates reported in this study are based on the 2.5th and 97.5th centiles of results generated from 1000 iterations of the model similar to a recent modelling study in the UK.5

Results

A total of 4080 cardiovascular deaths (2966 CHD deaths; 1114 Strokes) were reported in the age group of 25–85 years in 2010 in Ireland.

Table 3 shows the modest scenario estimates across the four food policy options studied in both men and women for CHD and stroke deaths prevented. Modest changes in food policy could result in approximately 395 (minimum 315; maximum 475) fewer cardiovascular deaths per year, a 10% overall reduction in CVD mortality in Ireland. Approximately 28% of the 395 fewer CVD deaths could be attributable to 0.5% decreased trans fat energy consumption levels; 22–1.0% decreased saturated fat energy consumption levels; 23% to decreased daily salt intake by 1 g; and 26% to one portion increased consumption of fruits and vegetables from the current consumption levels (table 3).

Table 3.

Estimated CHD and stroke deaths prevented by achievement of a modest scenario in specific food policy options by sex in Ireland, 2010

| CHD deaths prevented |

Stroke deaths prevented |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

||||||

| Food/nutrient | Deaths prevented (minimum; maximum) |

Deaths prevented (minimum; maximum) |

Deaths prevented (minimum; maximum) |

Deaths prevented (minimum; maximum) |

|||||

| Trans fat | 70 (56; 84) | 36.5% | 18 (14; 22) | 36.7% | 15 (12; 18) | 15.8% | 9 (7; 11) | 15.3% | |

| Saturated fat | 32 (26; 38) | 16.7% | 8 (6; 10) | 16.3% | 30 (24; 36) | 31.6% | 19 (15; 23) | 32.2% | |

| Salt intake | 41 (33; 49) | 21.3% | 11 (9; 13) | 22.5% | 24 (19; 29) | 25.3% | 15 (12; 18) | 25.4% | |

| Fruits/vegetables | 49 (39; 59) | 25.5% | 12 (10; 14) | 24.5% | 26 (21; 31) | 27.3% | 16 (13; 19) | 27.1% | |

| Subtotal | 192 (154; 230) | 100% | 49 (39; 59) | 100% | 95 (76; 114) | 100% | 59 (47; 71) | 100% | |

| Total (CHD) | 241 | ||||||||

| Total (stroke) | 154 | ||||||||

CHD, Coronary heart disease.

Table 4 shows the estimated number of CVD deaths that are potentially preventable with more ambitious but feasible food policy options. Modelled estimates of these scenarios indicate that approximately 1070 fewer CVD deaths could be prevented per year, representing an overall 26% reduction in annual CVD mortality in Ireland. As regards consumption of fatty acids, a 3% decrease in saturated fat energy consumption has the greatest potential impact on stroke deaths in both sexes, while a 1% decrease in trans fat energy consumption level has a relatively higher benefit on CHD deaths in both sexes. Reducing the average salt intake by 3 g/day would reduce CVD mortality by approximately 270 (minimum 220; maximum 325) deaths per year. Increasing fruits and vegetable portions to 3/day would result in the maximum health benefits—approximately 310 (minimum 250; maximum 370) fewer CVD deaths per year (table 4).

Table 4.

Estimated CHD and stroke deaths prevented by achievement of a feasible scenario in specific food policy options by sex in Ireland, 2010

| CHD deaths prevented |

Stroke deaths prevented |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

||||||

| Food/nutrient | Deaths prevented (minimum; maximum) |

Deaths prevented (minimum; maximum) |

Deaths prevented (minimum; maximum) |

Deaths prevented (minimum; maximum) |

|||||

| Trans fat | 140 (112; 168) | 27.7% | 36 (29; 43) | 27.9% | 30 (24; 36) | 11.2% | 19 (15; 23) | 11.2% | |

| Saturated fat | 95 (76; 114) | 18.8% | 24 (19; 29) | 18.6% | 89 (71; 107) | 33.4% | 56 (45; 67) | 33.1% | |

| Salt intake | 124 (99; 149) | 24.6% | 32 (26; 38) | 24.8% | 71 (57; 85) | 26.6% | 45 (36; 54) | 26.7% | |

| Fruits/vegetables | 146 (117; 175) | 28.9% | 37 (30; 44) | 28.7% | 77 (62; 92) | 28.8% | 49 (39; 59) | 29.0% | |

| Subtotal | 505 (404; 606) | 100% | 129 (103; 155) | 1100% | 267 (214; 320) | 100% | 169 (135; 203) | 100% | |

| Total (CHD) | 634 | ||||||||

| Total (Stroke) | 436 | ||||||||

CHD, Coronary heart disease.

Discussion

This modelling study has quantified avoidable CVD mortality in Ireland if the average diet of the Irish population is improved from its current consumption patterns with regard to the intake of fruits and vegetables, salt and dietary fats (both trans and saturated fats). The findings suggest that the achievement of a modest improvement in these four specific food policy options would save or delay approximately 395 CVD deaths (both CHD and stroke deaths) yearly in the Irish population. We also estimated a larger fall in CVD deaths approximating 1070 fewer CVD deaths on a yearly basis if more substantial but feasible food policy options were achieved. Similar patterns were observed in both. Recent modelling studies in the UK of a similar study design estimated the annual potential reductions in both CVD and cancer deaths as a result of changes in average population dietary intakes.5 6 Both these recent UK studies5 6 employed effect estimates that are derived from high-quality meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies.10 12–15

The 2010–2019 Irish national cardiovascular strategy11 has outlined targeted recommendations on specific eating habits within the lifetime of this policy report (table 1). The present study estimates are conservative considering the target levels set in this national strategy. Recent reports also indicate that the current dietary intakes of these four specific food components in the Irish population deviated considerably from the Irish dietary targets.16 17 The estimated mean daily salt intake in Ireland, for example, based on a PABA-validated 24 h urine analysis was 9.3 g/day in 2010.18 Such salt intakes are considerably higher than the set target of 6 g/day, while WHO has set a lower target of 5 g/day.19 A modelling study in the USA estimated that between 8% and 16% of the 565 000 CHD and stroke deaths could be averted in a year if dietary salt intake was reduced to 3 g/day.20 Children and the elderly are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of high salt intake, and the Irish national strategy11 has outlined in its policy document on paying particular attention to salt reduction in children.

The present study also suggests that increasing the consumption of fruits and vegetables to three portions a day is likely to offer the most benefit in terms of CVD deaths averted in a year, similar to the UK studies.5 6 In 2011, dietary fat provided 37% of food energy among 18-year-olds to 64-year-olds in Ireland, with 63% of the population exceeding the general recommended upper limit of 35% food energy from fat.17 Such gaps in current food policy choices and the achievable dietary standards indicate the need for a paradigm shift in the current public health food policy interventions. Ireland did show leadership in tobacco control when the first comprehensive nationwide smoke-free policy was introduced in March 2004. A similar leadership is crucial for legislating dietary food policies both at the national and at the EU level in the immediate future.

Limitations of the study

Modelling studies have inherent methodological limitations. Assumptions are to be made for statistical inferences and generalisation of findings. In this study, a few assumptions were made; for instance, risk factor effects were assumed to be independent, which could be an overestimation. Also, lag times were not addressed. However, changes can occur rapidly within a few years, as observed in Poland and Mauritius.21 22 Competing risks were not assessed. However, robust sensitivity analyses were performed to reduce such biases. In addition, the multiplicative nature of the model accurately reflects the quantitative estimates of relationships between food components, biological risk factors and health outcomes. The model also assumes a linear dose–response relationship between these factors that may not necessarily be true. The current model does not allow for changes in population dietary intakes to be modelled simultaneously but has potential for further development. Nevertheless, the model estimates are robust and similar to previous modelled estimates reported from the UK and the USA.5 6 20

Public health food policy interventions

The present study quantifies the potentially large reductions in premature CVD deaths if the recommended dietary intakes were achieved, consistent with international evidence. WHO has included reduced salt intake in food and replacement of trans fat with polyunsaturated fat among its ‘best buys’ for prevention and control of non-communicable diseases—interventions that it considers ‘not only highly cost-effective, but also cheap, feasible and culturally acceptable to implement’.1 The Food Safety Authority of Ireland (FSAI) in 2005 set a mean salt intake of 6 g/day as an ‘achievable’ target for the adult Irish population.23 However, there remains a long way to go for food policies to reach their full potential to encourage healthier eating. Food policies for health should be treated as a serious component of a well-functioning modern food economy. The Nuffield Council set out a useful ‘ladder of interventions’ to frame public health actions, but food policy is a matter for everyone and depends on partnerships and alliances at all levels to drive change.24 The challenge for the Irish government is that food policy cuts across departmental boundaries. The economic perspective, however, does provide governments with an incentive to act. New York City has been a shining example in this regard.25 In addition, there is a need for policy initiatives to reduce salt consumption or increase fruit and vegetable consumption by encouraging people to take the healthy option (eg, by lowering the prices of healthy foods compared to less healthy foods) and working with the food industry to reduce the salt content of processed foods.

Conclusions

This Irish food policy modelling study provides valuable estimates of the impact of population-level changes in dietary intake. Achieving a modest improvement in only four specific food components could potentially reduce CVD deaths by approximately 395 deaths in a single year. Doing nothing or simply monitoring this situation (political inaction) could result in dire public health consequences for the Irish population both in the short term and longer term.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Footnotes

Contributors: COK, ZK and IJP conceived the idea of the study; MOF and SC with ZK, COK and IJP designed the study. COK and ZK undertook the data analysis; ZK produced the tables and graphs; MOF, JW, IJP and SC provided input into the data analysis. ZK prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. MOF, IJP, JW and SC provided critical comments on the revised draft of the manuscript and contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a research grant from the Irish Health Research Board (ref no HRC/2007/13).

Competing interests: MOF is funded by EU and the UK MRC.

Ethics approval: Anonymised aggregate-level secondary data with no individual identifiers.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available

References

- 1.WHO World Health Organization diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. WHO Technical Report Series no. 916 Geneva: WHO, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capewell S, O'Flaherty M. Mortality falls can rapidly follow population-wide risk factor changes. Lancet 2011;378:752–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett K, Kabir Z, Unal B, et al. Explaining the decline in CHD mortality in Ireland 1985–2000. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:322–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kabir Z, Perry IJ, Critchley J, et al. Modelling coronary heart disease mortality declines in the Republic of Ireland, 1985–2006. Int J Cardiol 2013. (ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ÓFlahery M, Flores-Mateo G, Ninoaham K, et al. Potential cardiovascular mortality reductions with stricter food policies in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. WHO Bull World Health Org 2012;90:522–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scarborough P, Nnoaham KE, Clarke D, et al. Modelling the impact of a healthy diet on cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:420–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR), World Cancer Research Fund Food, nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington, DC: AICR, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 8.He FJ, MacGregor GA. A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes. J Hum Hypertens 2009;23:363–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagata C, Takatsuka N, Shimizu N, et al. Sodium intake and risk of death from stroke in Japanese men and women. Stroke 2004;35:1543–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strazzullo P, D'Elia L, Kandala NB, et al. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2009;339:b4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Changing Cardiovascular Health National Cardiovascular Strategy 2010–2019. Dublin: Department of Health and Children, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dauchet L, Amouyel P, Hercberg S, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Nutr 2006;136:2588–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dauchet L, Amouyel P, Dallongeville J. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Neurology 2005;65:1193–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakobsen MU, O'Reilly EJ, Heitmann BL, et al. Major types of dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of 11 cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1425–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mozaffarian D, Micha R, Wallace S. Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walton J. A summary report on food and nutrient intakes, physical measurements, physical activity patterns, and food choice motives. National Adult Nutrition Survey (NANS), 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrington J, Perry I, Lutomski J, et al. SLAN 2007: Survey of lifestyle, attitudes and nutrition in Ireland. Dietary habits of the Irish population. Department of Health and Children. Dublin: The Stationery Office, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry IJ, Browne G, Loughrey M, et al. Dietary salt intake and related risk factors in the Irish population: a report for Safefood. Cork: Safefood, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO European Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy 2007–2012. World Health Organization, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow G, Coxson P, et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2010;362:590–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zatonski W, Campos H, Willett W. Rapid declines in coronary heart disease mortality in Eastern Europe are associated with increased consumption of oils rich in alpha-linolenic acid. Eur J Epidemiol 2008;23:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uusitalo U, Feskens EJM, Tuomilehto J, et al. Fall in total cholesterol concentration over five years in association with changes in fatty acid composition of cooking oil in Mauritius: cross sectional survey. BMJ 1996;313:1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salt and Health: review of the scientific evidence and recommendations for public policy in Ireland. Food Safety Authority of Ireland, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuffield Council on Bioethics. 2007. Public health: ethical issues. http://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/public-health (accessed 21 Feb 2013)

- 25.Lichtenstein AH. New York City trans fat ban: improving the default option when purchasing foods prepared outside of the home. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:144–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.