Abstract

Objective

The HIV/AIDS burden in Israel is increasing. This study aims to describe the nationwide-HIV epidemiology in the last 30 years and highlight areas of concern in HIV/AIDS control.

Design

Descriptive study.

Setting

The National HIV/AIDS Registry in Israel.

Participants

All individuals who were reported with HIV/AIDS in Israel.

Primary outcome measures

Classification of HIV/AIDS cases by risk groups, calculation of annual trend analysis and estimation of HIV transmission rates by dividing the annual HIV/AIDS-incidence by the prevalence, while the number of newly diagnosed HIV/AIDS cases reported was a proxy of the incidence.

Results

From 1981 to 2010, 6579 HIV/AIDS cases were reported in an upward trend from 3.6 new HIV diagnoses/100 000 population in 1986 to 5.6 in 2010. Immigrants from countries of generalised epidemic (ICGE) comprised 2717 (41.3%) of all cases: 2089 (76.9%) were Israeli citizens and 628 (23%) were non-Israeli citizens, mostly migrant workers. The majority (N=2040) of ICGE Israeli citizens were born in Ethiopia. Only 796 (12.1%) of all HIV/AIDS cases were heterosexuals who were non-ICGE and not injecting drug users (IDUs). IDU comprised 13.4% (N=882) of all cases. Men who have sex with men (MSM) accounted for 33.2% (N=1403) of all men reported, while the annual number of MSM reported with HIV/AIDS has quadrupled between 2000 and 2010. It is estimated that the HIV point prevalences in 2010 for Ethiopian-born Israeli citizens, IDU and MSM aged 16–45 were 1805, 1492 and 3150, respectively. The crude estimated transmission rates among Israeli citizens, excluding the Ethiopian-born, was 10.5, while among Ethiopian-born Israeli citizens, IDU and MSM the rates were 3.6, 6.3 and 13.2, respectively.

Conclusions

The HIV/AIDS burden in Israel is low among heterosexuals and higher in risk-groups. Among these risk groups, the highest HIV transmission rate was in MSM, followed by IDU and ICGE. Culturally sensitive and focused prevention interventions should be tailored exclusively for each of the vulnerable risk groups.

Keywords: HIV, Migration, National registry

Article summary.

Article focus

Outlines HIV epidemiology in Israel, a developed country that receives increasing waves of migration from high HIV-burden areas.

Identifies key populations that are at high risk of HIV and estimates group-specific annual transmission rates.

Key messages

The HIV rate in Israel has increased moderately during the last 30 years, and in 2010 reported 5.6 cases/100 000 population.

Three key-risk populations were identified in Israel: men who have sex with men (MSM), injection drug-users (IDU) and heterosexuals originating in countries characterised by generalised HIV epidemic.

HIV transmission rates were highest for MSM, followed by IDU and Ethiopian-born Israeli citizens, who were mostly heterosexuals.

Israeli born heterosexuals, who are the majority of the Israeli society, showed the lowest HIV transmission rate.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The National HIV/AIDS registry is name-based and allows constant follow-up and updates, and it periodically crossmatched with the civil registry, health insurers, laboratories and health departments. The high completion rate has been maintained during the long study follow-up of 30 years.

The number of individuals from key populations who are living in Israel is not known, and therefore the HIV rates are estimated. Additionally, annual HIV notification was used as a proxy to calculate group-specific HIV transmission rates.

Introduction

Despite a slight decrease in the global incidence trend of HIV/AIDS,1 the estimated incidence rates in the USA2 and most European countries3 have remained stable. The AIDS epidemics in resource-rich countries are largely concentrated among specific key populations, such as men who have sex with men (MSM), injection-drug users (IDU) and immigrants from countries of generalised HIV epidemic (ICGE).

Israel is a developed country with a gross domestic product of $29 800/person,4 including nearly 7.7 million citizens, of whom nearly 2.5 million (∼32%)5 are non-Israeli born, and about 200 000 (∼2.5%) are migrants who are non-citizens who mostly arrived in Israel for labour purposes.6 The HIV/AIDS burden in Israel is low, while key populations, characterised by high-risk behaviours, are affected disproportionally.1 7 8

Knowledge about the trends and current dynamic of HIV/AIDS infection is essential for planning and evaluating the effectiveness of prevention efforts and budgeting purposes.9 There is compelling evidence that the treatment also serves as a public health instrument and reduces the community viral load and hence may reduce further infections.9 This study describes HIV/AIDS epidemiology in Israel during the last 30 years, based on a second-generation surveillance system, and highlights areas of concern in disease disparity between the affected communities.

Methods

Cases of both HIV and AIDS in Israel have been notified at the regional and central levels at the Ministry of Health since 1981 and recorded in the national HIV/AIDS registry (NHAR). The reports contain demographic (name, ID number, family status, address, country of birth and ethnicity, eg, Jewish or Arabic), behavioural and clinical data for each notification. From 2009, all new notifications should include CD4 count and treatment regimen. In cases of non-citizens, a photocopy of the passport or visa has to be attached. In response to the possible reporting bias of newly diagnosed patients who may refrain from disclosing their risk behaviour upon diagnosis, NHAR is periodically updated with continuous name-based reports from all the AIDS treatment centres and the regional health departments regarding behavioural and clinical changes. In addition, NHAR is crossmatched biannually with all four medical insurers to update NHAR regarding antiretroviral treatment (ART) initiation for each person. NHAR is also periodically crossmatched with the Civil Registry at the Ministry of Interior to update for citizens who left Israel or died. In addition to the known HIV-risk categories, a unique subcategory was added to ‘high-burden countries’—Ethiopian Jews—as they are encouraged to immigrate to Israel and are naturalised upon arrival. Most of the other migrants originating from ICGE are non-citizen labour migrants, and a minority are refugees.

The diagnosis of HIV in Israel requires two positive ELISA results and a confirmation by the western blot technique. HIV blood tests in Israel are performed free of charge and confidential, and are offered in all medical care facilities. Jewish Ethiopians who migrate to Israel are voluntary screened upon arrival while naturalised, and documented migrant workers are screened in their countries of origin before being granted a work visa. Inmates are also voluntarily screened upon incarceration.

The denominator used to determine the number of new HIV diagnoses per 100 000 population and denominators for other calculations were based on the official census published by the Israeli Bureau of Statistics.10 The estimation of the annual HIV transmission rate was described elsewhere.11 12 In short, transmission rates (T(x)) for a given year were calculated as the number of new HIV infections reported in the year × (I(x)) divided by the number of individuals known to be HIV infected (P(x)). The formula T(x)=(I(x)/P(x)) × 100 was used. The number of individuals known to be HIV infected was calculated by adding the number of newly diagnosed cases during that year to the number of individuals known to be HIV infected during the previous years and subtracting the number of people who died or left Israel. As the Civil Registry captures only Israeli citizens, the transmission rate was calculated only for citizens. In addition, Ethiopian Jewish migrants who were reported with HIV within 1 calendar-year following their arrival in Israel were excluded from this calculation. There are no data available in Israel about the rate of HIV-infected individuals who are unaware of their infection; however, based on reports from other developed countries, we conservatively estimated that 25% of the people who live with HIV/AIDS in Israel are unaware of their infection,13 14 and therefore adjusted the annual reported cases by a factor of 25% each year.

Trend analysis was performed by χ² to yield the linear-by-linear association test by the SPSS program V.18.0 (Statistical Package for Windows, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. As this was routine epidemiological analysis on the non-nominal data within a standard public-health database reporting system, ethical approval of an institutional review board was not required. No external funding was received for this study.

Results

Data and trends 1981–2010

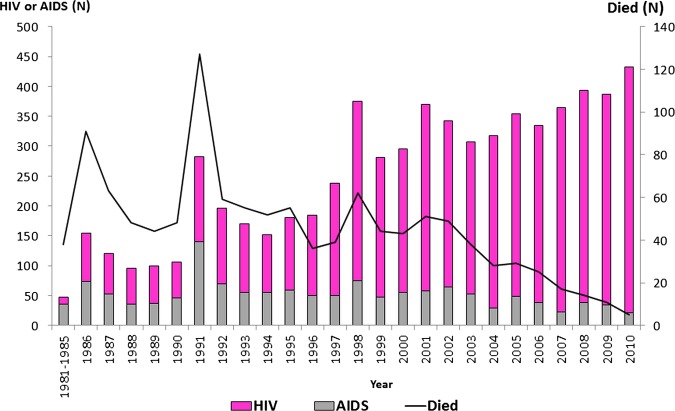

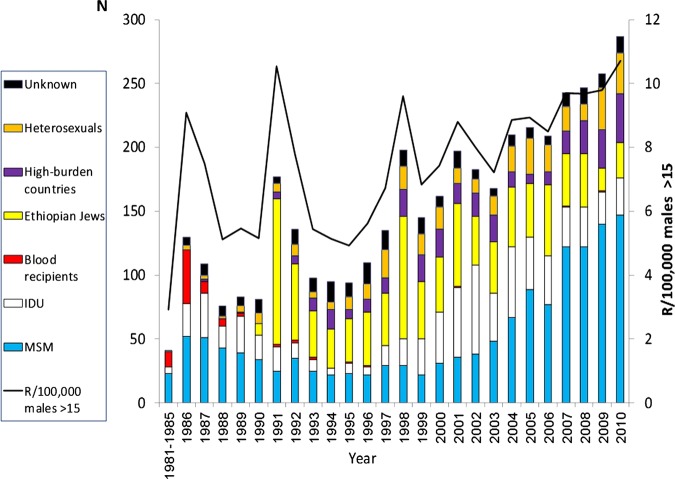

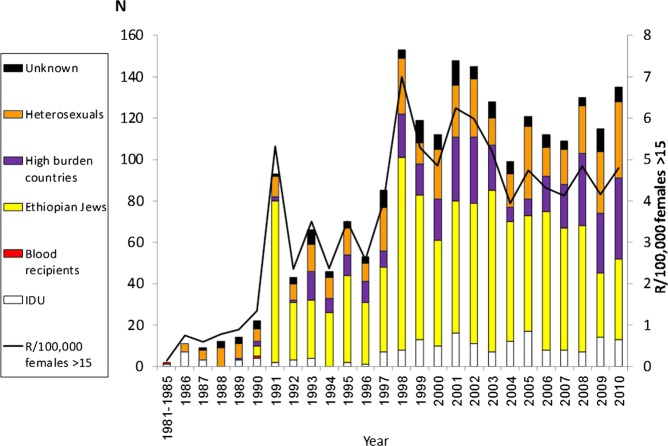

From 1981 and until 2010, 6579 HIV/AIDS-infected individuals were reported to NHAR, showing an upward trend (p=0.01). Of all the persons reported with HIV/AIDS, 63.9% (N=4208) were men, 34.5% (N=2268) were women and for 1.6% (N=103) the sex was not recorded. While the annual number of individuals newly diagnosed with HIV has increased (p<0.01), the number of individuals who were diagnosed with AIDS has decreased (p=0.02). During the study period, 1146 (17.4%) died and 184 (2.8%) have left Israel (figure 1). Between 1986 and 2010, the rate of individuals newly reported with HIV/AIDS in Israel increased from 3.6 to 5.6/100 000 population (p<0.01), while stabilising in the last decade at 4.5–5.6 (average 5.1) cases/100 000 (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Annual number of individuals in all 6579 newly reported HIV/AIDS cases and AIDS-related deaths in Israel, 1981–2010.

Figure 2.

Number of all 4208 new HIV/AIDS cases reported in Israeli men >15 years, by risk group, 1981–2010.

Figure 3.

Number of all 2268 new HIV/AIDS cases reported in Israeli women >15 years, by risk group, 1981–2010.

The mean annual male : female ratio was 1.8 (range: 1.2–12.2) and the mean age at reporting was 35.1 years (median 34, range: 0–88) for men and 31.7 years (median 31, range: 0–79) for women. While HIV/AIDS diagnoses among men have increased from the mid-1990s (p<0.001), the diagnoses among women have stabilised since the late 1990s (p=0.88). The annual HIV transmission rates among Israeli citizens, excluding Ethiopian Jewish migrants who were infected in their country of origin, decreased substantially from the 1980s, and stabilised at 10–11 in 2005–2010 (table 1).

Table 1.

Estimation of annual HIV transmission rates per 100 HIV-infected Israeli citizens*, 1981–2010

| Year of diagnosis | Number of reported cases | 25% Over the reported cases | Number who died | Individuals known to be HIV-infected | Higher estimation of individuals known to be HIV-infected | Crude transmission rate | Higher estimation of transmission rate | Year-by-year change | Higher estimation of year-by-year change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981–1985 | 40 | 50 | 36 | 4 | 14 | 1000.0 | 357.1 | −72.5 | −18.9 |

| 1986 | 146 | 183 | 89 | 53 | 63 | 275.5 | 289.7 | −58.9 | −56.0 |

| 1987 | 102 | 128 | 60 | 90 | 100 | 113.3 | 127.5 | −41.2 | −39.7 |

| 1988 | 80 | 100 | 46 | 120 | 130 | 66.7 | 76.9 | −21.1 | −19.7 |

| 1989 | 81 | 101 | 44 | 154 | 164 | 52.6 | 61.7 | −22.5 | −21.7 |

| 1990 | 75 | 94 | 42 | 184 | 194 | 40.8 | 48.3 | −23.3 | −22.8 |

| 1991 | 66 | 83 | 37 | 211 | 221 | 31.3 | 37.3 | −0.1 | 0.7 |

| 1992 | 80 | 100 | 31 | 256 | 266 | 31.3 | 37.6 | −18.6 | −18.3 |

| 1993 | 74 | 93 | 34 | 291 | 301 | 25.4 | 30.7 | −29.1 | −28.9 |

| 1994 | 57 | 71 | 32 | 316 | 326 | 18.0 | 21.9 | 10.0 | 10.4 |

| 1995 | 72 | 90 | 23 | 363 | 373 | 19.8 | 24.1 | −16.4 | −16.1 |

| 1996 | 69 | 86 | 15 | 416 | 426 | 16.6 | 20.2 | 26.9 | 27.4 |

| 1997 | 104 | 130 | 22 | 494 | 504 | 21.1 | 25.8 | −14.5 | −14.2 |

| 1998 | 103 | 129 | 25 | 572 | 582 | 18.0 | 22.1 | −21.9 | −21.8 |

| 1999 | 90 | 113 | 22 | 640 | 650 | 14.1 | 17.3 | 15.1 | 15.4 |

| 2000 | 119 | 149 | 22 | 735 | 745 | 16.2 | 20.0 | 18.1 | 18.3 |

| 2001 | 165 | 206 | 35 | 863 | 873 | 19.1 | 23.6 | −9.3 | −9.2 |

| 2002 | 173 | 216 | 35 | 998 | 1008 | 17.3 | 21.5 | 17.3 | 21.5 |

| 2003 | 122 | 153 | 20 | 1097 | 1107 | 11.1 | 13.8 | 11.1 | 13.8 |

| 2004 | 170 | 213 | 9 | 1258 | 1268 | 13.5 | 16.8 | 13.5 | 16.8 |

| 2005 | 213 | 266 | 22 | 1448 | 1458 | 14.7 | 18.3 | 14.7 | 18.3 |

| 2006 | 162 | 203 | 14 | 1593 | 1603 | 10.2 | 12.6 | 10.2 | 12.6 |

| 2007 | 209 | 261 | 10 | 1790 | 1800 | 11.7 | 14.5 | 11.7 | 14.5 |

| 2008 | 214 | 268 | 8 | 1996 | 2006 | 10.7 | 13.3 | 10.7 | 13.3 |

| 2009 | 252 | 315 | 6 | 2241 | 2251 | 11.2 | 14.0 | 11.2 | 14.0 |

| 2010 | 271 | 339 | 4 | 2508 | 2518 | 10.8 | 13.5 | 10.8 | 13.5 |

*Excluding Israeli citizens who were known to be infected in Ethiopia.

MSM accounted for 33.4% (N=1403) of all male cases reported during the study period. The number of MSM notified with HIV/AIDS in Israel has quadrupled from 34 cases that were reported in 2000 to 148 cases in 2010. During the same period, the proportion of MSM versus all other men notified annually with HIV/AIDS has increased from 20.4% to 50.9%. Their mean age at notification was 34.4 years (median 33, range: 17–78) and most (N=821, 58.5%) lived in the Tel Aviv region. The majority (N=1277, 91.0%) of all MSM registered were Israeli citizens, of whom 1224 (95.8%) were Jewish and 63 (4.2%) were Arabs.

ICGE comprised 2717 (41.3%) of all HIV/AIDS cases. Of all the ICGE reported, 2089 (76.9%) were Israeli citizens and 628 (23%) were non-citizens, mostly migrant workers. The majority (N=2040, 97.6%) of ICGE-Israeli citizens were born in Ethiopia. Of those, 1238 (60.7%) were infected in Ethiopia before migration or in the first 2 years of stay in Israel following their arrival. As they were screened shortly after arrival in Israel, we found that 802 (39.3%) who were HIV negative on arrival were infected after staying in Israel for more than 2 years. The mean annual male : female ratio of HIV-infected Israeli citizens who were born in Ethiopia was 1 (range: 0.5–2.1). The mean age at diagnosis was 38.6 (median 35, range: 13–88) for men and 33.4 (median 31, range: 13–79) for women. Of the 628 ICGE who were non-citizens, the sex was recorded for 608 (97.6%) individuals, and the annual average male : female ratio was 1.4 (range: 0.4–6). The mean age at reporting for 494 (78.7%) individuals whose ages were recorded was 36.7 (median 36, range: 13–60) for men and 33.9 (median 33, range: 15–79) for women. The annual proportion of ICGE non-citizens of all HIV/AIDS-cases has increased between 2005 and 2010 from 4.2% to 16.5%. Between 2000 and 2010, 16.1% of ICGE non-citizen women were HIV-infected and had already clinical AIDS, while this proportion was equal to 6.1% among ICGE Israeli citizens women.

IDU comprised 882 (13.4%) of all HIV/AIDS cases. The annual average male : female ratio was 4.1 (range: 1–10). The mean age at reporting for the 846 (95.9%) individuals whose ages were recorded was 32.6 for men (median 31, range: 14–66) and 31.2 (median 30, range: 17–58) for women. Most (N=460, 87%) of the IDU diagnosed after 2000 were born in the former Soviet Union and immigrated to Israel after 1990.

Only a minority (N=796, 12.1%) of all cases reported between 1981 and 2010 were heterosexuals without a known risk behaviour. The annual average male : female ratio was 0.9 (range: 0.2–1.8). The mean age at reporting for the 757 (95.1%) individuals whose ages were recorded was 40.8 (median 39, range: 14–81) for men and 33.4 (median 32, range: 15–74) for women.

Of the 781 individuals (11.9% of all HIV/AIDS cases) who did not belong to any of the aforementioned key-risk populations, 109 (13.9%) acquired their infection through blood products and 206 (26.3%) were infected vertically. No key-risk behaviour was recorded for 466 (59.8%) individuals.

2010 data

Of all the 5249 individuals who were living with HIV/AIDS in Israel in 2010, 2268 (43.2%) were ICGE (of those, 1805 were Ethiopian-born citizens), 630 (12%) were IDU, 656 (12.5%) were heterosexuals without known risk behaviour and 1403 (26.7%) were MSM. MSM comprised 36% of all men who were living with HIV/AIDS in 2010. No risk group was reported for the remaining 292 (5.6%). The crude estimated transmission rate in 2010 among Israeli citizens, excluding Ethiopian Jewish migrants, was 10.5 and in the upper bound estimation it was 13.1.

It is estimated that 150 000 Israeli citizens of Ethiopian origin and 20 000 drug-users (Dr Haim Mehl, Israeli antidrug authority, personal communication) were living in Israel in 2010. We also assume that MSM in Israel comprised ∼3% of all men aged 16–45 years (∼94 000 men), as reported from other developed countries.15 16 Based on these assumptions, HIV point prevalences in 2010 were 1805/100 000 for Ethiopian-born Israeli citizens, 3150/100 000 for IDU and 1492/100 000 for MSM aged 16–45 years.

The estimated HIV transmission rates for Ethiopian-born Israeli citizens, IDU and MSM were 3.6–3.8, 6.3–6.6 and 13.2–14.8, respectively. That is, for example, each 100 HIV-infected Israeli citizens of Ethiopian origin are estimated to transmit the virus to about four otherwise seronegative persons per year. The average initial CD4 count of 427 (49.1%) from 869 newly diagnosed HIV individuals in 2009 and 2010 was 380 cells/mm3 (median=368, range: 3–1865). Of the 4182 Israeli citizens who were living with HIV/AIDS at the end of 2010, 2925 (70%) were on ART.

Discussion

The number of new HIV diagnoses in Israel since 1981 and the annual rate per 100 000 are relatively lower than in most western European countries and the USA, both in the general population and in the key risk groups.2 17 Three groups which are disproportionally affected by HIV/AIDS were identified: MSM who were mostly Israeli-born, IDU who were mainly foreign-born citizens who immigrated from the former Soviet Union after 1990 and heterosexuals who were ICGE. The latter are divided into Jewish immigrants from Ethiopia, who are Israeli citizens, and migrant workers. HIV epidemiology in Israel is similar to that reported from Western Europe,3 reflecting similar immigration patterns of ICGE and migrants from Eastern Europe, comparable societal values respecting gay communities and the availability of resources to facilitate culturally sensitive interventions to control the epidemic.

As demonstrated in other developed countries, the number of new HIV/AIDS diagnoses continues to rise in spite of the widespread use of ART and despite aggressive prevention efforts targeting the affected communities. The relatively high HIV transmission rate in Israel compared with the 4.1% reported from the USA from 2006 to 200812 may be associated with the higher transmission rate among MSM and the continuous influx of ICGE arriving in Israel. It is also possible that behavioural changes among susceptible populations aiming to reduce the risk of infection are slower than those among the increasing number of individuals infected with HIV in Israel. Nevertheless, in spite of the constant influx of ICGE and the rise in the number of individuals who are known to be infected in Israel, the overall estimated transmission rate in Israel has declined throughout the study period. Additionally, the decrease in the number of individuals who were late presenters (detected with clinical AIDS upon diagnosis rather than HIV) is decreasing, which might be a result of successful interventions aiming to promote HIV testing.

MSM in Israel, in agreement with publications from other resourc-rich countries,18–20 are at high risk for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.21 Despite MSM’s awareness of their greater vulnerability, the number of new infections continues to rise disproportionally. The effectiveness of most biomedical innovations aiming to reduce HIV infection among MSM, such as developing potent vaccine, rectal bactericide or using postexposure therapy, is limited.21 22 In response to the rising HIV-transmission dynamics among MSM in Israel in recent years, the National campaign has changed its focus in 2010 from safe sex messages, which were used in the last decade, to HIV test promotions to ensure earlier diagnosis and timely initiation of HIV treatment and care. The interventions were conducted by concerted actions: advertising in gay-related electronic sites, establishing an interactive internet site (http://www.safe-sex.co.il), upgrading all HIV-testing kits from the third to fourth generation (ie, antibody and antigen detection) and approving rapid and anonymous HIV tests in the community.

The Israeli society is polarised, as on the one hand it segregates and discourages intrareligious or intraracial marriages, while on the other hand, it is relatively open to variation in sexual orientations. These social conducts may limit sexual networking of heterosexual Israeli citizens with ICGE, while allowing MSM to enjoy a relatively safe environment. Thus, bridging between the affected, yet distinct communities to the wider heterosexual population is probably limited.

This study is subject to several limitations. First, the exact number of MSM, IDU and non-citizens ICGE is not known, and therefore the calculations of the rates of new HIV diagnoses for specific populations are only estimated. Second, sexual behaviour and drug-use habits are subject to reporting bias. Nevertheless, this study’s results are based on robust and continuous surveillance efforts, and the name-based NHAR is updated and verified periodically. Third, all Ethiopian Jewish immigrants are screened for HIV shortly after arrival in Israel, while ICGE non-citizens are not. Therefore, accurate reporting of the point prevalence upon arrival is most likely present in the former case, while under-reporting is possible in the latter. Lastly, the calculations of the estimated transmission rates should be read with care, mainly for two reasons: first, the calculation assumes that all transmissions occur within the specific subpopulations; it does not take into consideration the possible bridging between the affected communities; second, the rate of reported HIV/AIDS cases was roughly used as a proxy for the incidence.12 However, as the calculations were performed in a similar fashion for all the subpopulations, they demonstrate the differences in the dynamic of the infection and allow comparisons between the different key populations, thus supporting decisions in prioritising prevention efforts.

In summary, the HIV/AIDS burden in Israel is defined by a low-level epidemic as categorised by WHO.23 The number of new HIV diagnoses reported each year is low among heterosexuals but higher in more-at-risk populations, similar to reports from other developed countries. Implementation of effective prevention interventions requires sustainable political commitment and a multidimensional approach to reflect the demographic diversity and the changing epidemiology, address the social norms of affected high-risk groups and maximise opportunities derived from evolving technological advances.19

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ms Zehuvit Wiexelbom for her exceptional maintenance of the National HIV/AIDS Registry.

Footnotes

Contributors: ZM initiated the study, performed data analysis and wrote the first draft; RW and DC revised the paper; IG revised the paper and approved the final version and YL analysed the data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The database is managed and updated by the department of tuberculosis and AIDS in the Israeli Ministry of Health. Further data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) UNAIDS report on the global epidemic 2010. UNAIDS/10.12E|JC2035E. http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/AIDSScorecards.htm (accessed 28 Aug 2012). [PubMed]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV surveillance—United States, 1981–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:689–93 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO Regional Office for Europe HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2010. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Central Intelligence Agency The world factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/ (accessed 28 Aug 2012).

- 5.United Nations Development Program Human development report 2009: overcoming barriers, human mobility and development. New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Israeli Population and Immigration Authority http://www.piba.gov.il/PublicationAndTender/ForeignWorkersStat/Documents/summary2010.pdf (accessed 28 Aug 2012).

- 7.Chemtob D, Grossman Z. The epidemiology of adult and adolescent HIV infection in Israel, a country of immigration. Int J STD AIDS 2004;15:691–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mor Z, Pinsker G. HIV/AIDS in Israel: periodic epidemiological report 1981–2010. http://www.old.health.gov.il/Download/pages/PeriodicReport2011.pdf (accessed 28 Aug 2012).

- 9.Fenton KA. Changing epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in the United States: implications for enhancing and promoting HIV testing strategies. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:S213–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Statistical Abstract of Israel 2011- No 62. Central Bureau of Statistics, Jerusalem, Israel. http://www.cbs.gov.il/reader/shnatonenew_site.htm (accessed 28 Aug 2012).

- 11.Holtgrave DR, Hall HI, Rhodes PH, et al. Updated annual HIV transmission rates in the United States, 1977–2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;50:236–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holtgrave DR, Hall HI, Prejean J. HIV transmission rates in the United States, 2006–2008. Open AIDS J 2012;6:26–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janseen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS 2006;20:1447–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA 2008;300:520–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, et al. Estimated HIV Incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e17502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosher WD, Chandra A, Jones J. Sexual behavior and selected health measures: men and women 15–44 years of age, United States, 2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 362 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Implementing the Dublin Declaration on partnership to fight HIV/AIDS in Europe and central Asia: 2010 progress report. Stockholm: ECDC, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mor Z, Davidovich U, McFarlane M, et al. Gay men who engage in substance use and sexual risk behavior: a dual-risk group with unique characteristics. Int J STD AIDS 2008;19:693–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mor Z, Shohat T, Goor Y, et al. Risk behavior and sexually transmitted diseases in gay and heterosexual men attending an STD clinic in Tel Aviv, Israel: a cross sectional study. IMAJ 2012;14:147–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levi I, Mor Z, Anis E, et al. MSM, risk behavior and HIV infection: integrative analysis of clinical, epidemiological and laboratory databases. Clin Infect Dis 2011;51:1363–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Wit JB, Prestage GP, Dufin IR. Gay men: current challenges and emerging approaches in HIV prevention. NSW Public Health Bull 2012;21:65–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Safren SA, Wingood G, Altice FL. Strategies for primary prevention that target behavioural changes. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(Suppl 4):S300–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization and UNAIDS Initiating second generation HIV surveillance systems: practical guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO/HIV/2002.17), 2002 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.