Abstract

Introduction

In vivo estimation of beta2-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (β2*-nAChR) availability with molecular neuroimaging is complicated by competition between the endogenous neurotransmitter ACh and the radioligand [123I]5-IA-85380 ([123I]5-IA). We examined whether binding of [123I]5-IA is sensitive to increases in extracellular levels of ACh in humans, as suggested in non-human primates (1).

Methods

Six healthy subjects (31±4yrs) participated in one [123I]5-IA SPECT study. After baseline scans, physostigmine (1–1.5mg) was administered IV over 60 min, and additional scans were collected (8–14h).

Results

We observed a significant reduction in VT/fp (total volume of distribution) after physostigmine (29±17% cortex, 19±15% thalamus, 19±15% striatum, and 36±30% cerebellum; p<.05). This reflected a combination of a region-specific 7–16% decrease in tissue concentration of tracer and 9% increase in plasma parent concentration.

Conclusion

These data suggest that increases in ACh compete with [123I]5-IA for binding to β2*-nAChRs. Additional validation of this paradigm is warranted, but it may be used to interrogate changes in extracellular ACh.

Keywords: brain β2*-nAChRs, [123I]5-IA SPECT, physostigmine, extracellular ACh

INTRODUCTION

In vivo molecular imaging studies of muscarinic and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors have provided substantial contributions to our understanding of disorders related to cholinergic dysfunction, but are limited by the lack of a suitable method for measuring fluctuations in brain ACh levels. For example, our evaluation of beta2-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (β2*-nAChR) availability in unmedicated individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) demonstrated significantly lower receptor availability compared to control subjects (2); however, quantitation of total β2-nAChR binding sites in postmortem brain revealed no differences in MDD compared to control samples, suggesting that increased ACh levels in vivo may have resulted in lower β2-nAChR availability and apparent lower receptor density.

In vivo imaging of β2-nAChRs is possible with the high affinity radioligand [123I]-3-[2(S)-2-azetidinylmethoxy]pyridine ([123I]5-IA) (3) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging (4). [123I]5-IA has slow dissociation from the receptor-ligand complex, good specific-to-nonspecific binding ratio, and high selectivity for β2*-nAChRs (4, 5). [123I]5-IA has been used to measure β2-nAChR availability in animals (5–7) and humans (8, 9); however, there are no published studies demonstrating in vivo measurements of brain levels of ACh in human subjects. Studies in non-human primates suggest that competition between ACh and radioligand may be detectable (1, 10), and mycrodialysis studies in rodents and nonhuman primates suggest an at least 200% increase in brain ACh levels after acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor administration (REFS). [123I]5-IA binding in the thalamus was decreased (15%) following challenge with 0.067 mg/kg physostigmine in one study, and was consistently decreased (14–17%) following challenge with 0.2 mg/kg physostigmine (1).

Here, we used [123I]5-IA SPECT to determine whether physostigmine-induced increases in extracellular ACh in the brain compete with [123I]5-IA binding in vivo in humans. We hypothesized that physostigmine-induced increases in extracellular ACh would significantly reduce [123I]5-IA binding.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Six healthy control subjects (3 men, 3 women, 31±4 years) signed informed consent and completed the study approved by the Yale University School of Medicine, Veterans Affairs Health Care System, and University of Toronto Institutional Review Boards. Eligibility was evaluated via structured interview, behavioral assessments, physical examination, laboratory blood tests, urine drug screen, and an electrocardiogram. Subjects had never smoked, had no life-time psychiatric, neurological, or medical history, and no contraindications for participation in one magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan and one [123I]5-IA SPECT scan day.

Mood symptoms were measured with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (11) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (12). State and trait anxiety symptoms were measured with Spielberger’s State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (13). All were administered at intake and on scan day (before and after physostigmine administration).

MRI scan was obtained on a 3 Tesla Siemens Scanner (Germany; Magnetom Trio A Tim System; Software: Numaris/4; Version: syngo MR B17) to guide placement of regions of interest for SPECT scans (Series 1: 3 plane localizer; Series 2: Sag 3d tfl; 250fov; 1 mm thick slices; 176 slices total; TE 3.53; TR 2500; TI 1100; FA 7; 256×256 2 averages).

[123I]5-IA was synthesized and administered for the duration of the study as described in (8) using a bolus plus constant infusion paradigm (B/I 7.3±0.2h) with a total injected dose (accounting for decay) of 390.2±13.2 MBq. Six hours following injection of [123I]5-IA, a simultaneous transmission emission protocol (STEP) scan and 3 equilibrium 30-min emission scans (90 min total) were obtained on a Phillips PRISM 3000 XP (Cleveland, OH) SPECT camera. Subjects were administered glycopyrrolate (0.2 mg, IV) to minimize peripheral muscarinic side-effects, followed by administration of physostigmine (a reversible AChE inhibitor that crosses the blood-brain barrier) over 1h (1–1.5mg, IV). Thereafter, up to 3 sets of 30-min emission scans were acquired (each set 90min in duration; 20–30min break between each set; In subject #5, the “[123I]5-IA infusion was interrupted after the collection of 5 post-physostigmine scans, thus data thereafter is not shown. In the other 5 subjects, all 9 post-physostigmine scans were collected). Venous blood samples were collected pre- and post-physostigmine to correct for individual differences in radiotracer metabolism and protein binding. Pulse and blood pressure were measured before and after injection of [123I]5-IA, and prior to and following physostigmine administration.

SPECT images were analyzed as described in (8). Regional [123I]5-IA uptake (β2*-nAChR availability) was calculated as VT/fp, where VT is brain regional activity divided by metabolite-corrected plasma activity and fp is the free fraction of parent in plasma. Plasma for fp calculation was collected at 4 time points and applied to calculate corresponding VT/fp: The first was prior to [123I]5-IA administration (baseline); The second was immediately prior to physostigmine administration; The third was immediately following physostigmine administration; And the fourth was at the end of the last set of post-drug scans. Specifically, fp values from 1 and 2 above were averaged and applied to baseline VT to estimate baseline VT/fp; fp from 3 (immediately post physostigmine administration) was applied to VT from first and second post physostigmine scanning sessions to estimate VT/fp for those time points; and fp from 4 was applied to the last scanning session. Regions studied were frontal, parietal, anterior cingulate, temporal and occipital cortices (averaged to obtained single cortical value), striatum, thalamus and cerebellum. Change in radioligand binding to β2*-nAChRs was calculated as percent difference between VT/fp before as compared to VT/fp after physostigmine administration for each post-drug SPECT scan. To demonstrate the use of non-displaceable binding (VND/fP) previously calcuated (14) and estimate specific radioligand binding (BPF (previously VS/fp), we subtracted a fixed value (19.4 mL·cm−3) of VND/fP from VT/fp for each brain region and scan.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS v19.0 (Armonk, New York). Statistical significance was set at p≤0.05, two-tailed. Repeated measures of analysis of variance (df = 5) were used to assess within-subject differences in pharmacokinetic parameters and mood variables pre- to post-physostigmine administration. Standard deviation (SD) was calculated for all outcome variables (Table 1) and is represented as error bars in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Outcome values for each subject at baseline and 2–4hrs after physostigmine injection.

| # |

fp baseline |

fp pre physo |

fp post physo |

fp end study |

VT/fp baseline | VT/fp post | VS/fp baseline | VS/fp post | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thal | CB | Cort | Str | Thal | CB | Cort | Str | Thal | CB | Cort | Str | Thal | CB | Cort | Str | |||||

| 1 | 32.6% | 37.0% | 36.4% | 39.2% | 151.0 | 73.9 | 54.0 | 77.8 | 140.9 | 64.7 | 49.4 | 71.9 | 131.6 | 54.5 | 34.6 | 58.4 | 121.5 | 45.3 | 30.0 | 52.5 |

| 2 | 37.0% | 36.1% | 36.5% | 37.5% | 131.4 | 25.2 | 51.3 | 70.9 | 102.9 | 20.0 | 38.4 | 56.9 | 112.0 | 5.8 | 31.9 | 51.5 | 83.5 | 0.6 | 19.0 | 37.5 |

| 3 | 35.9% | 34.7% | 32.9% | 28.6% | 129.9 | 40.3 | 51.3 | 69.0 | 111.5 | 33.0 | 42.0 | 56.9 | 110.5 | 20.9 | 31.9 | 49.6 | 92.1 | 13.6 | 22.6 | 37.5 |

| 4 | 25.8% | 25.0% | 25.9% | 34.2% | 180.5 | 75.8 | 64.9 | 93.1 | 140.2 | 58.0 | 48.1 | 74.1 | 161.1 | 56.4 | 45.5 | 73.7 | 120.8 | 38.6 | 28.7 | 54.7 |

| 5 | 33.7% | 37.4% | 44.3% | 47.3% | 125.4 | 69.4 | 49.4 | 68.5 | 81.5 | 49.6 | 34.4 | 51.7 | 106.0 | 50.0 | 30.0 | 49.1 | 62.1 | 30.2 | 15.0 | 32.3 |

| 6 | 36.6% | 35.4% | 39.3% | 111.1 | 55.6 | 40.9 | 65.1 | 111.0 | 55.4 | 40.0 | 67.8 | 91.7 | 36.2 | 21.5 | 45.7 | 91.6 | 36.0 | 20.6 | 48.4 | |

| Mean | 33.6% | 34.3% | 35.9% | 37.4% | 138.2 | 56.7 | 52.0 | 74.1 | 114.7 | 46.8 | 42.0 | 63.2 | 118.8 | 37.3 | 32.6 | 54.7 | 95.3 | 27.4 | 22.6 | 43.8 |

| SD± | 4.17% | 4.65% | 6.19% | 6.87% | 24.4 | 20.4 | 7.8 | 10.22 | 22.8 | 17.0 | 5.8 | 9.2 | 24.4 | 20.4 | 7.8 | 10.2 | 22.8 | 17.0 | 5.8 | 9.2 |

| Not able to draw last blood sample for subject # 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Thal: Thalamus, CB: Cerebellum, Cort: Mean Cortex, Str: Striatum

Baseline: values prior to physostigmine administration, Post: values at 2–4 hrs post physostigmine administration – at the time of greatest displacement of the radioligand by ACh.

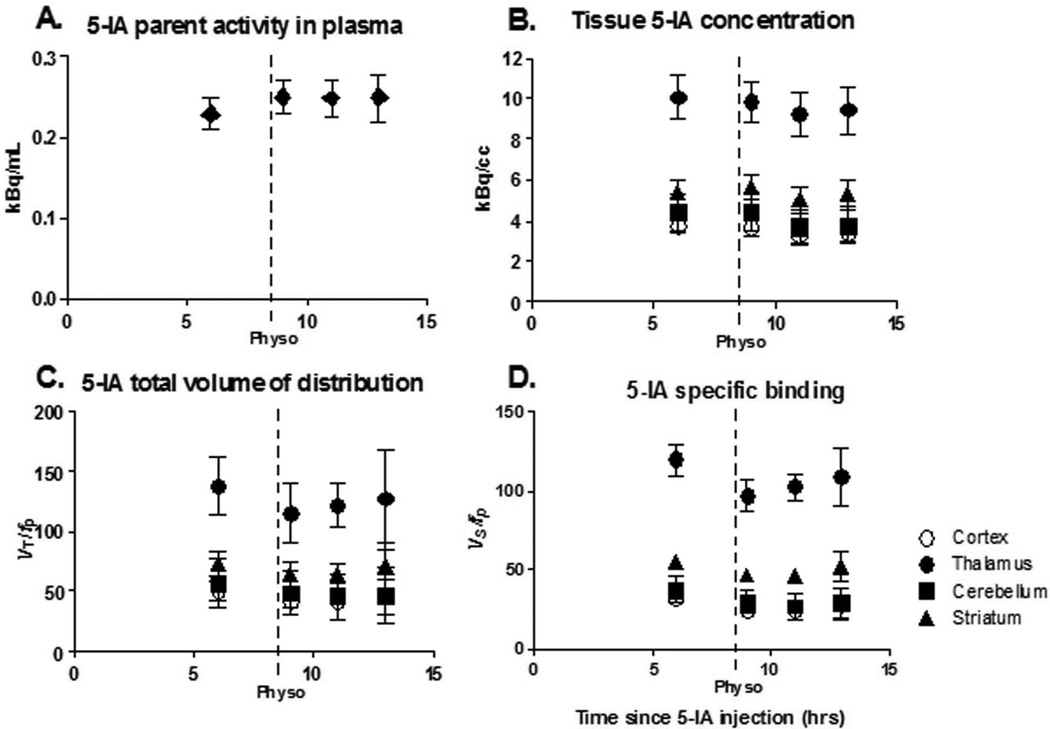

Figure 1.

The first point in each graph represents baseline data obtained starting 6 h after beginning tracer infusion when a state of equilibrium is achieved, and provided the baseline specific binding. Following completion of the baseline scans, physostigmine was administered I.V. (1.0–1.5 mg over 1 h, arrow). At the onset of the physostigmine infusion, scanning was resumed for up to 9 h. Bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). A. Plasma [123I]5-IA concentration (kBq/mL) (total parent) measured during [123I]5-IA constant infusion in healthy volunteers. Following physostigmine administration there was a significant 8% increase in mean plasma [123I]5-IA concentration as compared to before physostigmine administration. B. Tissue [123I]5-IA concentration (kBq/cc) in thalamus (circles), striatum (triangles), cortex (open circles), and cerebellum (squares) measured during [123I]5-IA constant infusion. We observed 7–15% region specific decrease in [123I]5-IA tissue concentration after physostigmine challenge. C. [123I]5-IA total volume of distribution (VT/fp) in thalamus (circles), striatum (triangles), cortex (open circles), and cerebellum (squares) measured during [123I]5-IA constant infusion. VT/fp values measured after the physostigmine infusion were significantly reduced (14–18% region specific) compared to the baseline values. D. [123I]5-IA specific binding (BPf) in thalamus (circles), striatum (triangles), cortex (open circles), and cerebellum (squares) measured during [123I]5-IA constant infusion. BPf values measured after the physostigmine infusion were significantly reduced (19–36% region specific) compared to the baseline values.

RESULTS

Nonsmoking status was verified by negligible urine cotinine (0 ηg/mL), plasma cotinine (< 2ηg/mL) and nicotine (<1.0 ηg/mL) levels, and exhaled carbon monoxide (0.7 ± 0.8 ppm). There were no significant differences in subjects’ mood or anxiety pre- to post- physostigmine administration (p>0.2).

Administration of physostigmine did not significantly alter free fraction (p>0.2); but resulted in significantly increased [123I]5-IA total plasma parent activity for all subjects (9.1±8.6%, t=−2.56, p=0.05 1h post challenge, stable thereafter; Figure 1A), and significantly increased free parent activity (9.9±7.7%, t=−3.1, p=0.03) at 1h post challenge, which was not significant thereafter (t=−1.2, p=0.30 6h post challenge).

Equilibrium [123I]5-IA binding (<5% change in receptor availability/h), was reached 6–8h after injection (average change across subjects: 2.7±1.7%/h thalamus, 3.6±2.2%/h striatum, 2.5±2.5%/h cortex, 1.7±1.6%/h cerebellum). [123I]5-IA tissue concentration was reduced after physostigmine, with the peak reduction reached 2–4h post-challenge (Figure 1B), the same time point for the greatest decrease in [123I]5-IA binding after nicotine administration (14, 15). A reduction in [123I]5-IA tissue concentration was observed in all brain regions 2–4h post-challenge: thalamus 7.8±4.7%, striatum 7.0±0.9%, mean cortex 12.7±18.1%, and cerebellum 16.5±13.6%.

Administration of physostigmine significantly reduced total volume of distribution of [123I]5-IA at 2–4 hrs post physostigmine administration. The peak average decrease in VT/fp was 18±%11 in cortical regions (F=15.4, p=0.01), 17±12% in thalamus (F=11.3, p=0.02), 14±11% in striatum (F=11.0, p=0.02), and 17±10% in cerebellum (F=10.4, p=0.02) (Figure 1C and Figure 2A).

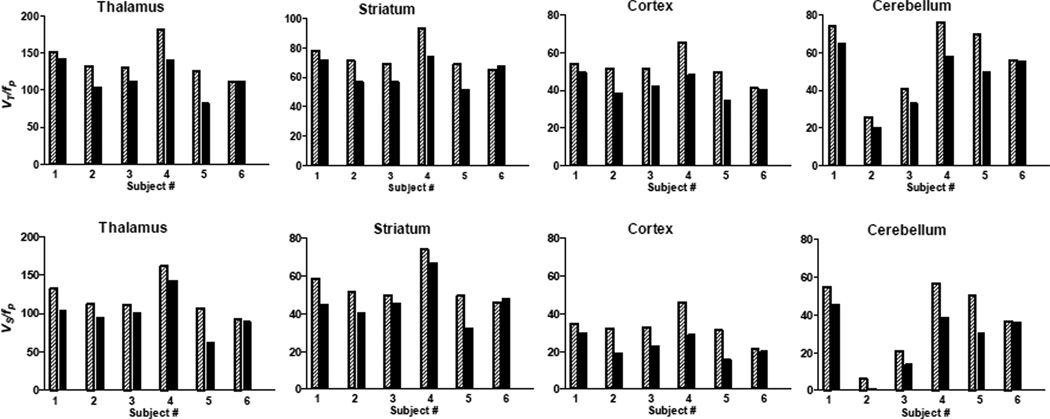

Figure 2.

A. β2-nAChR availability (VT/fP) before (shaded bars) and after (solid bars) physostigmine injection for each subject. Thalamus: Percent displacement of 5-IA for subjects 1–6 were −7%, −22%, −14%, −22%, −35%, −0%, respectively. Striatum: Percent displacement of 5-IA for subjects 1–6 was −8%, −20%, −18%, −20%, −25%, −4%, respectively. Cortex: Percent displacement of 5-IA for subjects 1–6 were −9%, −25%, −18%, −26%, −30%, −2%, respectively. Cerebellum: Percent displacement of 5-IA for subjects 1–6 was −12%, −20%, −18%, −23%, −28%, 0%, respectively. B. Specific radioligand binding (Vs/fP) before (shaded bars) and after (solid bars) physostigmine injection for each subject. Thalamus: Percent displacement of 5-IA for subjects 1–6 were −8%, −25%, −17%, −25%, −41%, 0%, respectively. Striatum: Percent displacement of 5-IA for subjects 1–6 was −10%, −27%, −24%, −26%, −34%, +5%, respectively. Cortex: Percent displacement of 5-IA for subjects 1–6 were −13%, −40%, −29%, −36%, −50%, −6%, respectively. Cerebellum: Percent displacement of 5-IA for subjects 1–6 was −17%, −90%, − 35%, −32%, −40%, −1%, respectively.

Subtraction of VND/fp revealed a greater percent reduction in specific binding of [123I]5-IA. The peak average decrease in BPf was 29±17% in cortical regions (F=15.4, p=0.01), 19±15% in thalamus (F=11.3, p=0.02), 19±15% in striatum (F=11.0, p=0.02), and 36±30% in cerebellum (F=10.4, p=0.02) (Figure 1D and Figure 2).

There was a significant decrease in pulse rate following physostigmine administration (12.3 ± 13.3%; p=0.08) but no significant changes in blood pressure (p>0.7).

DISCUSSION

We evaluated whether increases in extracellular levels of the endogenous neurotransmitter ACh competes with [123I]5-IA binding to β2*-nAChRs. The goal of this study was to establish a novel paradigm to interrogate the cholinergic system in vivo in humans and to provide a more comprehensive interpretation of our (2, 16) and other’s (17) findings in populations with compromised cholinergic systems. Physostigmine administration resulted in a significant decrease in total [123I]5-IA binding, suggesting that [123]5-IA is sensitive to extracellular ACh levels. This reduction in [123]5-IA binding is similar to that achieved after smoking a denicotinized cigarette ((18) and unpublished data from our group). Denicotinized cigarettes have 0.05mg of nicotine, equivalent to smoking about 1 puff from a regular cigarette. However, given that 1) nicotine is a direct agonist at β2*-nAChRs and has high affinity for the receptor, and 2) physostigmine-induced radioligand displacement has an indirect action, it is not surprising that administration of a high dose of physostigmine leads to a comparable displacement of [123I]5-IA as administration of 0.05mg nicotine.

The degree of reduction of [123]5-IA binding in thalamus following physostigmine challenge is in line with a previous study in non-human primates (1), although the amount of injected physostigmine was 10-fold less in the present human study. The similarity in the decrease of radioligand binding may be attributed to lower levels of ACh release in anesthetized non-human primates compared to awake humans, or to physiological differences between species. The observed decrease in [123I]5-IA binding here and in the previous study (1) was due to a combination of increases in [123I]5-IA plasma concentration and reduction in [123I]5-IA tissue concentration. Thus, administration of physostigmine appears to alter radioligand distribution throughout the body, affecting tracer levels in the blood. Specifically, the increase in ACh due to administration of physostigmine occurs throughout the body, and thus the peripheral nAChR binding sites previously available for [123I]5-IA to bind are now also occupied by ACh. The displacement of [123I]5-IA in the body likely causes more free radioligand to circulate in plasma. Thus, the tissue concentration alone is not an accurate measure for the evaluation of physostigmine-induced ACh displacement of [123I]5-IA, and total volume of distribution or specific ligand binding should be employed in this paradigm.

There are several limitations to this study. First, physostigmine may have an allosteric effect on radioligand binding to β2*-nAChRs; however, physostigmine did not alter [123I]5-IA binding in rat in vitro studies, and had significantly lower affinity for nAChR as compared to [123I]5-IA (physostigmine: 25,000 nM vs [123I]5-IA: 0.010 nM).(5) Thus, competition between physostigmine and [123I]5-IA for binding to the receptor is not a likely explanation for the observed outcome of decreased [123I]5-IA binding post physostigmine administration. Second, use of VND/fp obtained from a previous sample in control smokers may not be applicable in a study of nonsmokers. Further, the use of a fixed value for nondisplaceable binding across regions may not accurately reflect the observed regional differences in specific binding, especially for regions with lower levels of specific binding. Specifically, the change in thalamic VT/fp and BPf was 16% and 19%, respectively, whereas the change in lower binding region (i.e., cerebellum) was 17% and 36%, respectively. Thus, BPf values were reported with the purpose of showing how the estimate of VND/fp may be used in future studies. Finally, the small sample size allows drawing only preliminary conclusions and limits examination of sex or age differences.

CONCLUSION

We developed a paradigm to interrogate the ACh system in vivo in human subjects and observed a significant decrease in total binding of [123I]5-IA following physostigmine challenge, consistent with an increase in endogenous extracellular ACh levels. This imaging tool may have enormous potential to facilitate the development of innovative medicines aimed at modulating the cholinergic system.

Acknowledgements

We thank the technologists at the Institute for Neurodegenerative Disorders for conducting the scanning protocol and Louis Amici (Yale University) for metabolite and protein binding analyses of the radiotracer. Financial support: Salary support was provided by VA Career Award (I.E.), MH077681 (M.R.P.), K12DA00167 (J.H.), K01DA20651 (K.P.C.), and K01MH092681 (I.E.). Studies were supported by the VA National Center for PTSD and Yale University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: Authors Irina Esterlis, Kelly Cosgrove, Jonas Hannestad, Frederic Bois, Richard Carson, Marina Picciotto, and Andrew Sewell have no conflict of interest or financial disclosures to report. Dr. Seibyl has equity interest in Molecular Neuroimaging, LLC. Dr. Tyndale has participated in one day advisory meetings for Novartis and McNeil. Dr. Laruelle was a consultant for AMGEN, PFIZER and ROCHE and a GSK shareholder at the time of completion of this study and is now a full time employee of UCB PHARMA.

References

- 1.Fujita M, Al-Tikriti M, Tamagnan G, et al. Influence of acetylcholine levels on the binding of a SPECT nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ligand [123I]5-I-A-85380. Synapse. 2003;48:116–122. doi: 10.1002/syn.10194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saricicek A, Esterlis I, Maloney K, et al. Persistent β2*-Nicotinic Acetylcholinergic Receptor Dysfunction in Major Depressive Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abreo M, Lin N-H, Garvey D, et al. Novel 3-Pyridyl Ethers with Subnanomolar Affinity for Central Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. J Med Chem. 1996;39:817–825. doi: 10.1021/jm9506884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaupel D, Mukhin A, Kimes A, Horti A, Koren A, London E. In vivo studies with [125I]5-IA 85380, a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor radioligand. NeuroReport. 1998;9:2311–2317. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199807130-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukhin A, Gundisch D, Horti A, Koren A, Tamagnan G, Kimes A, et al. 5-Iodo-A-85830, an α4β2 subtype-selective ligand for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:642–649. doi: 10.1124/mol.57.3.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujita M, Tamagnan G, Zoghbi S, et al. Measurement of α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors with [123I]5-I-A85830 SPECT. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1552–1560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chefer S, Horti A, Lee K, et al. In vivo imaging of brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors with 5-[123I]iodo-A-85830 using single photon emission computed tomography. Life Sci. 1998;63:355–360. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Staley J, Dyck Cv, Weinzimmer D, et al. Iodine-123-5-IA-85380 SPECT Measurement of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Human Brain by the Constant Infusion Paradigm:Feasibility and Reproducibility. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1466–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujita M, Seibyl J, Vaupel D, et al. Whole body biodistribution, radiation-absorbed dose and brain SPET imaging with [123I]5-I-A-85830 in healthy human subjects. Eur J Nuc Med. 2002;29:183–190. doi: 10.1007/s00259-001-0695-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valette H, Bottlaender M, Dollé F, Coulon C, Ottaviani M, Syrota A. Acute effects of physostigmine and galantamine on the binding of [18F]fluoro-A-85380: a PET study in monkeys. Synapse. 2005;56:217–221. doi: 10.1002/syn.20145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck S, Ward C, Mendelsohn M, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spielberger C, Corsuch R, editors. Manual for State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esterlis I, Cosgrove K, Batis J, et al. Quantification of smoking induced occupancy of β2-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: estimation of nondisplaceable binding. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2010;51:1226–1233. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.072447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esterlis I, Mitsis E, Batis J, et al. Brain β2*-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor occupancy after use of a nicotine inhaler. International Journal Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;14:389–398. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710001227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Souza D, Esterlis I, Carbuto M, et al. Lower β2*-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Availability in Smokers with Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:326–334. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis J, Villemagne V, Nathan P, et al. Relationship between nicotinic receptors and cognitive function in early Alzheimer's disease: a 2-[18F]fluoro-A-85380 PET study. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;90:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brody A, Mandelkern M, Costello M, et al. Brain nicotinic cetylcholine receptor occupancy: effect of smoking a denicotinized cigarette. International J of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;12:305–316. doi: 10.1017/S146114570800922X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]