Abstract

Objective

To describe the relationships among sedation, stability in physiological status, and comfort during a 24-hour period in patients receiving mechanical ventilation.

Methods

Data from 169 patients monitored continuously for 24 hours were recorded at least every 12 seconds, including sedation levels, physiological status (heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry), and comfort (movement of arms and legs as measured by actigraphy). Generalized linear mixed-effect models were used to estimate the distribution of time spent at various heart and respiratory rates and oxygen saturation and actigraphy intervals overall and as a function of level of sedation and to compare the percentage of time in these intervals between the sedation states.

Results

Patients were from various intensive care units: medical respiratory (52%), surgical trauma (35%), and cardiac surgery (13%). They spent 42% of the time in deep sedation, 38% in mild/moderate sedation, and 20% awake/alert. Distributions of physiological measures did not differ during levels of sedation (deep, mild/moderate, or awake/alert: heart rate, P = .44; respirations, P = .32; oxygen saturation, P = .51). Actigraphy findings differed with level of sedation (arm, P < .001; leg, P = .01), with less movement associated with greater levels of sedation, even though patients spent the vast majority of time with no arm movement or leg movement.

Conclusions

Level of sedation most likely does not affect the stability of physiological status but does have an effect on comfort.

The need for sedative therapy in critical care adults receiving mechanical ventilation is well established; 85% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients are given intravenous sedatives to help attenuate the anxiety, pain, and agitation associated with mechanical ventilation.1–4 The overall goals of the sedation are to provide stability in physiological status and comfort.4–6 However, use of inappropriately high or low levels of sedation in critically ill adults has marked risks. Inappropriately high levels of sedation, which are associated with the use of continuous intravenous infusions of sedatives,7 may lead to alterations in respiratory drive, inability to maintain and protect the airway, and unstable cardiovascular status,8 as well as prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation and ventilator-associated pneumonia.9–11 In addition, sedation increases the risk for depressive symptoms, delirium, and delusional memories of the ICU stay.12,13 Conversely, inadequate levels of sedation may result in agitation, placing intubated patients at risk for self-extubation, unstable hemodynamic status, and physical harm or injury.14

Sedation management is a multidisciplinary process, but in most ICUs, nurses are primarily responsible for making the decisions about administration and titration of sedatives.15–17 Nurses adjust sedation according to a wide range of information, including subjective assessments of patients’ amnesia and comfort needs, need to prevent self-injury by patients, efficiency of care, and the nurses’ own beliefs and interactions with patients’ families.15,18,19 Decisions to alter sedation on the basis of this non-systematic information may result in either inadequate or excessive sedation.18,19 Therefore, the first step in improving patients’ outcomes is to systematically describe physiological status and comfort outcomes for various levels of sedation.

Although sedation protocols reduce the duration of mechanical ventilation20–23 and ICU costs,22,24 most protocols use a single measure of sedation, either a sedation scale or processed electroencephalographic findings, to titrate sedative therapy.25 Levels of sedation should differ according to an individual patient’s needs and disease process, resulting in deep levels of sedation for some patients and lighter levels for others.4 However, the extent to which these various levels of sedation actually achieve sedation outcomes of a stable physiological status and comfort is unknown. Therefore, the specific aim of this prospective study was to describe the relationship among sedation, stability of physiological status, and comfort during a 24-hour period in patients receiving mechanical ventilation.

Methods

Setting and Sample

This prospective observational study was conducted at the Virginia Commonwealth University Health System, Richmond, Virginia, in a 779-bed tertiary care medical center in 3 types of ICUs: surgical trauma, cardiac surgery, and medical respiratory.

The sample was drawn from all patients admitted to these ICUs who were intubated, receiving mechanical ventilation, 18 years or older, and expected to have at least 24 hours of mechanical ventilation. Exclusion criteria were presence of a tracheostomy (rather than endotracheal intubation), because the discomfort associated with a trache os tomy tube may be different than that associated with an endotracheal tube26; administration of paralytic agents; chronic, persistent neuromuscular disorders (eg, cerebral palsy, Parkinson disease), because the disorders would affect patients’ movements and study measurements; and head trauma or stroke, which might also affect patients’ movements. Patients were recruited during a 2-year data collection period. The planned sample size of 175 patients was determined by using a power calculation based on testing for a significant partial correlation (R2 > 0.2) in a multivariate analysis (at α = .05) with at least 80% power. A total of 176 patients met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study; of these, 169 had data sufficient for analysis.

Key Variables and Their Measurement

Sedation

The level of sedation was quantified by using a continuous, objective measure, the Patient State Index (PSI), obtained by using a SEDLine (Masimo Corp, Irvine, California), which has quantitative features of electroencephalograms that display clear differences between sedative states.27 The PSI has a range of 0 to 100; decreasing values indicate increasing sedation. PSI values were downloaded from the device via a thumb drive and then were stored in a notebook computer. Significant differences have been documented between mean PSI values obtained during different sedation states.27,28 Several investigators29–32 have compared the PSI with subjective sedation tools and found significant relationships between the PSI and the values obtained with the various tools.

Stability of Physiological Status

The stability of physiological status was measured as cardiovascular activity (heart rate) and oxygenation (respiratory rate, hemoglobin saturation of oxygen as recorded by pulse oximetry [SpO2]). Heart rate data were acquired every second by using the Criticare Systems Scholar II monitor (Criticare Systems Inc, Waukesha, Wisconsin) and a type I, 3-electrode electrocardiographic sensor; the data were stored in the computer via a serial port. Respiratory rate was documented for every breath and was acquired from the ventilator via a NICO cardiopulmonary monitor device (Respironics, Parsippany, New Jersey) and stored in the computer via a serial port. SpO2 data were acquired via an oximetry sensor of the NICO device, which sends the analog signal to a BIOPAC MP150 data acquisition system (BIOPAC Systems, Inc, Goleta, California) with a 125-Hz sampling frequency. The data were then imported to a text file that provided a mean value of SpO2 for every second and were stored in the computer.

Comfort

Because the study required continuous measures of sedation outcomes, the use of typical, intermittently measured comfort-discomfort or pain scales was not ideal. In addition, a patient’s movement can be a large influence when the adequacy of sedation is evaluated.2 Therefore, wrist and ankle actigraphy were used to record a continuous level of activity as a surrogate measure of agitation and discomfort. The actigraphy unit contains a single omnidirectional accelerometer that integrates occurrence, degree, and intensity of motion to produce activity counts and is capable of sensing any motion with minimal acceleration of 0.01g. Actigraphy has been used to monitor activity levels in participants for sleep, circadian rhythms, pain, and drug response and is a reliable method of assessing activity and agitation in critical care.33,34 In a prospective evaluation of 20 adult medical ICU patients, actigraphy was sensitive to changes in sedation and the findings significantly correlated with scores on the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (R = 0.58; P < .001), and the Comfort Scale (R = 0.62; P < .05).33 In addition, actigraphy counts correspond to a variety of behavior states (calmness, restlessness, agitation) common in critically ill patients and are indicative of comfort.35 Wrist and ankle actigraphy data were acquired through Motionlogger actigraphy devices (Basic Octagonal Motionlogger, Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc, Ardsley, New York) by using the PIM mode and an epoch time of 1 second, which had been time synchronized with the computer and then downloaded via a USB port from the actigraphy cradle.

Demographics

Patients’ characteristics that may affect sedation outcomes were documented, including age, ICU (reflecting type of critical illness and population), duration of endotracheal intubation (in hours), ICU length of stay (in hours), and type and amount of sedatives and analgesics administered.

Patients with greater severity of illness may require greater depths of sedation to facilitate mechanical ventilation and optimize oxygenation and a stable hemodynamic status.4 Therefore, severity of illness at the time of enrollment in the study was measured by using the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III.36,37 The APACHE III total score ranges from 0 to 299 and consists of the following subscores: vital signs/laboratory, pH/PCO2, neurological, age, and chronic health. Scoring is done by using the worst values for the first ICU day. The APACHE scoring system has been validated38 and is widely used to stratify patients into well-defined groups38,39 and to ensure that research treatment and control groups have equivalent severity of illness.40,41

Procedures

The study was approved by the appropriate institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained from each patient’s legally authorized representative. Patients were enrolled during any period of mechanical ventilation so long as they met the inclusion criteria. Sedation outcomes were evaluated during a continuous 24-hour period, starting at any time and continuing until the same time on the next day. Before monitoring and collection of physiological data, all devices and monitors were time synchronized and time stamped with respect to the computer’s real-time clock. During the 24-hour measurement period, the acquired data were stored and regularly inspected and reviewed for quality, accuracy, and integrity to reduce variability in patients’ values.

By design, the measurement intervals varied for the factors studied. Some factors varied only between patients (eg, demographics and disease severity), and other factors varied within a patient across time (eg, level of sedation). Because raw data were collected throughout the study period at different sampling intervals depending on the data acquisition system, that is, every second (for physiological and actigraphy data) and every 1.2 seconds (for PSI data), data means were determined for 12-second intervals to provide a common interval across intervals and to smooth the data. The mean value for each variable during every 12-second interval was used for data analysis. Predetermined interval ranges (Table 1) for each response measure were used to classify the mean measure during each 12-second interval (eg, heart rate, 101–120/min). Finally, during each 12-second interval, the PSI score was categorized as deep (≤60), mild/moderate (61–80), or awake/alert (>80).29,42

Table 1.

Classification of physiological and comfort measures and sedation into interval rangesa

| Heart rate, beats per minute |

Actigraphyb | Respirations, breaths per minute |

Oxygen saturation % |

Sedationc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–60 | 0 | 0–10 | ≤87.5 | 0–10 |

| 61–80 | 1–5 | 11–15 | 87.6–90.0 | 11–20 |

| 81–100 | >5 | 16–20 | 90.1–92.5 | 21–30 |

| 101–120 | 21–25 | 92.6–95.0 | 31–40 | |

| 121–140 | 26–30 | 95.1–97.5 | 41–50 | |

| 31–35 | 97.6–100 | 51–60 | ||

| 36–40 | 61–70 | |||

| 71–80 | ||||

| 81–90 | ||||

| 91–100 |

Data ranges displayed reflect the data obtained during the study.

Actigraphy: 0, no movement; greater than zero up to 5, little movement; >5, meaningful amount of movement.

Patient State Index, range 0 to 100.

Data Analysis

Patients’ characteristics were described by using standard descriptive measures (means, standard deviations, counts, and proportions). Generalized linear mixed-effect models were used to estimate the distribution of PSI, heart rate, respirations, SpO2, and arm and leg actigraphy findings. More specifically, the percentage of time a “typical” patient would spend in each interval was estimated. The models were also used to estimate the distribution of heart rate, respirations, SpO2, and arm and leg actigraphy findings during different levels of sedation (deep, mild/moderate, awake/alert). That is, the percentage of time a typical patient would spend in each interval at each level of sedation was estimated.

Results

A total of 176 patients were enrolled in the study. Of these, 7 were not included in the analysis (4 were extubated before data collection, 2 had data collection equipment failures, and 1 withdrew from the study), resulting in 169 patients in the sample.

As shown in Table 2, patients had a mean age of 54 years and were primarily men, non-Hispanic, and white or African American. More than half were from the medical respiratory ICU. Mean APACHE III scores, duration of intubation, and length of ICU stay are also shown in Table 2. Patients were enrolled in the study for mean of 22.2 hours (because of extubations before the 24-hour goal). Data related to the type and amount of sedatives and analgesics administered are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Sample demographics

| Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 54.0 | 13.7 | 19–83 |

| APACHE III score | 74.3 | 27.4 | 22–181 |

| Median | IQR | Range | |

| Days of intubation | 7.5 | 4.1–12.8 | 1.1–95.2 |

| Days in intensive care unit | 13.4 | 8.8–21.3 | 2.7–77.7 |

| Days of intubation at study enrollment | 2.8 | 1.4–5.9 | 0.01–33.1 |

| Days of mechanical ventilation since end of study | 2.8 | 0.7–5.9 | 0–92.8 |

| Duration of study, h | 24.0 | 23.8–24.0 | 2.8–25.7 |

| No. of patients (n = 169) | %a | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 103 | 61.0 |

| Female | 66 | 39.1 |

| Race | ||

| White | 78 | 46.2 |

| Black/African American | 83 | 49.1 |

| Asian | 2 | 1.2 |

| Other | 2 | 1.2 |

| Unknown/not reported | 4 | 2.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 3 | 1.8 |

| Non-Hispanic | 166 | 98.2 |

| Intensive care unit | ||

| Medical respiratory | 88 | 52.1 |

| Surgical trauma | 59 | 34.9 |

| Cardiac surgery | 22 | 13.0 |

| Reason for intubation | ||

| Respiratory distress | 76 | 45.0 |

| Airway control | 62 | 36.7 |

| Respiratory arrest | 6 | 3.6 |

| Hypoxemic respiratory failure | 19 | 11.2 |

| Ventilatory failure | 5 | 3.0 |

| Both hypoxemic respiratory and ventilatory failure | 1 | 0.6 |

Abbreviations: APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; IQR, interquartile range.

Because of rounding, not all percentages total 100.

Table 3.

Type and total dose of sedatives and analgesics administered in a 24-hour period

| Before study enrollment |

During study enrollment |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | No. of patients | Median | IQR | No. of patients | Median | IQR |

| Analgesic | ||||||

| Fentanyl, µg | 117 | 1200 | 742.5–1910.4 | 119 | 1250 | 720.0–2100 |

| Morphine, mg | 32 | 13 | 4–47.5 | 25 | 23 | 5.5–66.5 |

| Hydromorphone, mg | 3 | 6 | 4–36 | 2 | 41.25 | 35–47.5 |

| Sedative | ||||||

| Midazolam, mg | 91 | 42 | 16–84 | 82 | 52 | 24.3–93 |

| Propofol, µg | 33 | 3303 | 1515–4549.1 | 30 | 2690.5 | 1369–3528.5 |

| Lorazepam, mg | 29 | 6 | 2–38.8 | 23 | 9 | 2–43 |

| Haloperidol, mg | 7 | 5 | 4–10 | 4 | 7.5 | 4.3–23.1 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Sedation Outcomes

A total of 42% (n = 71) of the patients spent the majority of their time in deep sedation, 38% (n = 64) in mild/moderate sedation, and 20% (n = 34) awake/alert as defined by the PSI. Relationships between the percentage of time spent in each sedation state and the duration of mechanical ventilation before the study began were significant. Specifically, as duration of mechanical ventilation before the study increased, patients tended to spend a significantly lower percentage of time in deep sedation (Spearman ρ = −0.20; P = .02), significantly more time in mild/moderate sedation (Spearman ρ = 0.26; P = .04), and more time awake/alert (Spearman ρ = 0.15; P = .06). The percentage of time spent in the 3 sedation states was not significantly associated with APACHE III scores, with the exception of the relationship between increased APACHE III scores and decreased percentage of time in deep sedation that approached significance (Spearman ρ = 0.24; P =.09).

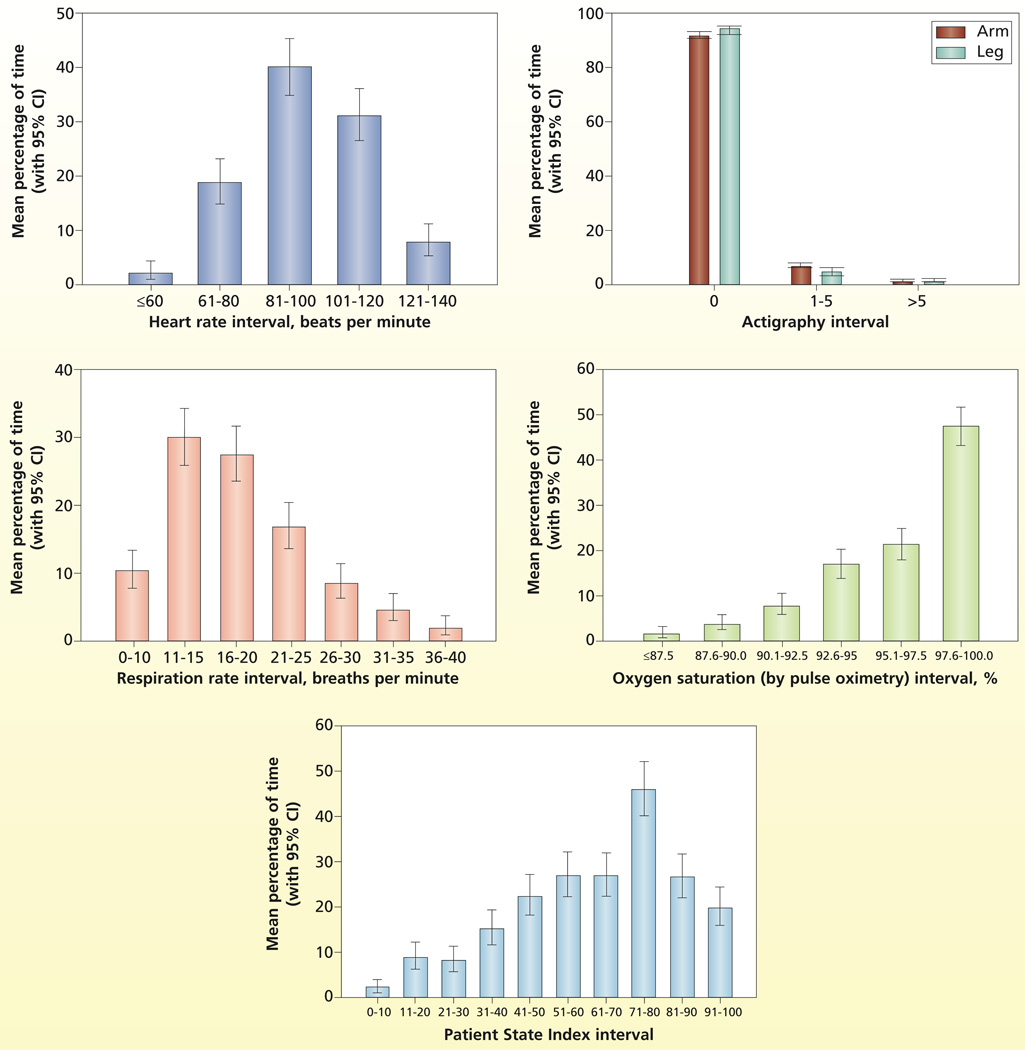

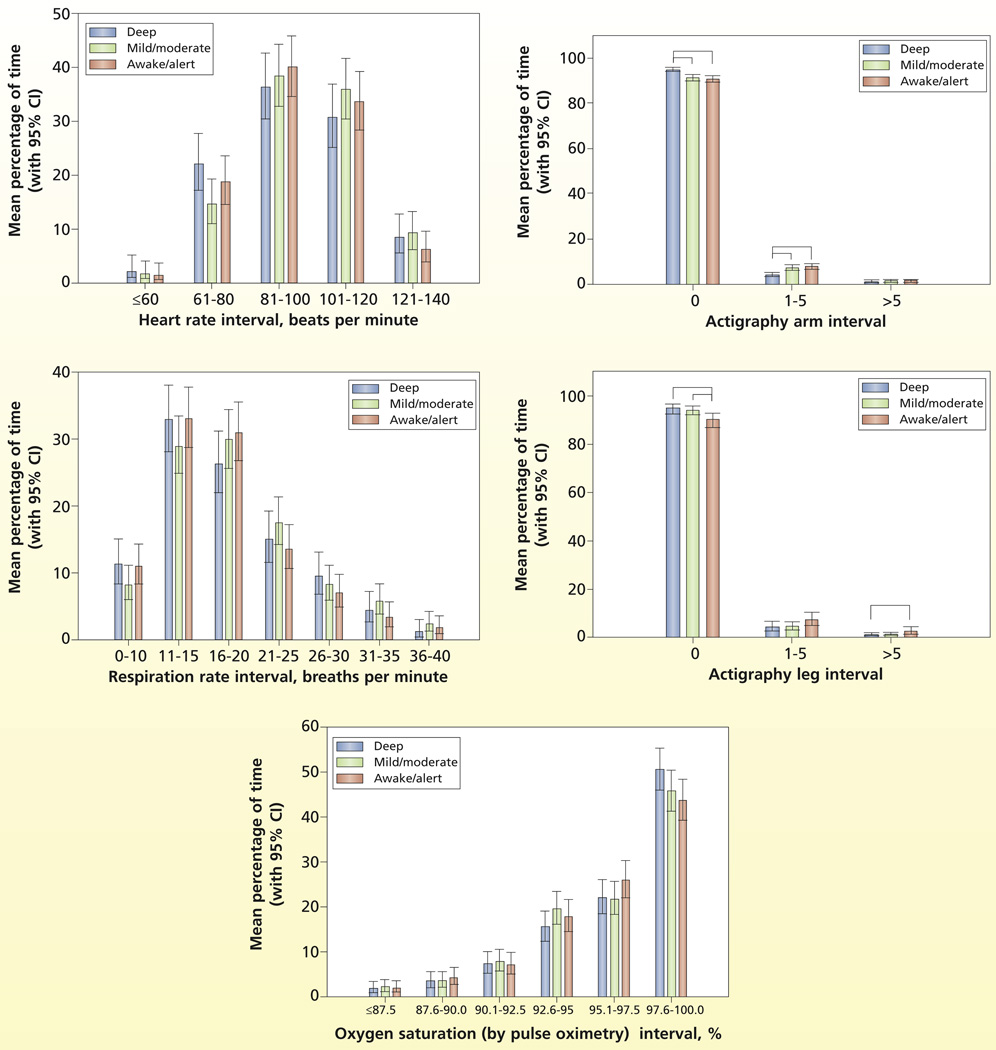

The estimated distribution (time spent in each interval) for the physiological and comfort measures and sedation are plotted in Figure 1. The distributions for the physiological variables (heart rate, respirations, SpO2) are as expected for this population and are well distributed across intervals. However, actigraphy findings, the comfort measure, have a skewed distribution, indicating little movement by patients across all levels of sedation. The distributions of the physiological and comfort measures adjusted for level of sedation are plotted in Figure 2. No evidence indicated that the distributions of the physiological measures differed during the 3 levels of sedation (heart rate, P = .44; respirations, P = .32); SpO2, P = .51). However, comfort as measured by actigraphy differed significantly with level of sedation as expected (arm actigraphy, P < .001 and leg actigraphy, P = .01). Specifically for arm movement, the percentage of time spent with no movement (arm actigraphy = 0) was significantly greater during deep sedation (95.05%) than during mild/moderate (91.43%) or awake/alert (90.81%) sedation levels, and the percentage of time with little arm movement (actigraphy score 1–5) was significantly greater during mild/moderate (7.31%) or awake/alert (7.82%) sedation levels than during deep (4.17%) sedation levels. For leg movement, the percentage of time with no leg movement (leg actigraphy score = 0) was significantly greater during deep (95.08%) or mild/moderate (94.31%) levels of sedation than during awake/alert (90.34%) levels, and the percentage of time with a meaningful amount of leg movement (leg actigraphy score >5) was significantly greater during awake /alert (2.37%) levels of sedation than during deep (0.56%) sedation.

Figure 1.

Estimated distribution of time spent in various intervals.

Figure 2.

Estimated distribution of time spent in intervals adjusted for level of sedation.

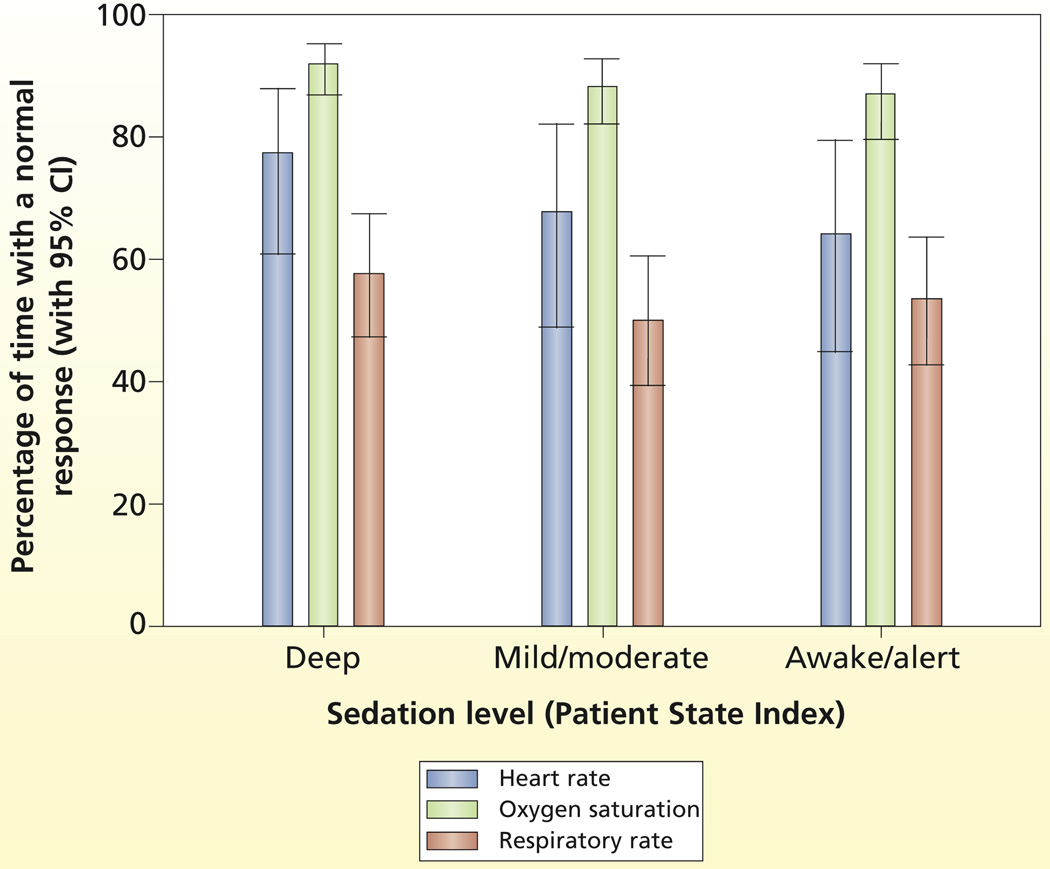

To guide sedation intervention strategies to achieve a stable physiological status, nurses may use normal ranges for physiological variables (ie, heart rate 60–100/min, respirations 12–20/min, arterial oxygen saturation 95%).2 For patients’ movement, the goal is to achieve a calm behavior state (neither too much nor too little spontaneous movement).4 On the basis of previous research,35 mean actigraphy levels during a calm state varied for arm (from 5.87 to 7.85) and leg (from 3.03 to 4.11) actigraphy. Thus, further post hoc analyses with generalized linear mixed-effect models were done to estimate and compare the percentage of time a typical patient would spend in these normal physiological ranges and in a calm state as a function of deep, mild/moderate, and awake/alert levels of sedation.

The estimated percentage of time with normal physiological measures during each PSI state is shown in Figure 3. Heart rate was in the normal range 64% to 77% of the time during the PSI states but was most likely to be normal during deep sedation. SpO2 was normal 87% to 92% of the time during the PSI states. Respirations were only normal 50% to 58% of the time during the 3 states but were most likely to be normal during deep sedation. However, patients were in a calm state less than 0.2% of the time regardless of sedation level.

Figure 3.

Percentage of time within normal ranges for physiological variables by level of sedation.

The percentage of time with a normal physiological or comfort response was compared for the 3 PSI states. The odds ratios for a normal response (vs a nonnormal response) for each sedation state for each response measure are summarized in Table 4. Confidence intervals that do not include the number 1 are significant at P = .05. In summary, all response measures were statistically different between the 3 PSI states. For example, the odds of a normal heart rate were 90% greater during deep sedation than during an awake/alert state, 62% greater during deep sedation than during mild/moderate sedation, and 18% greater during mild/moderate sedation than during an awake/alert state. Further, the odds of a normal SpO2 were 67% greater during deep sedation than during an alert/awake state, and the odds of normal respiratory rate were 36% greater during deep sedation than during mild/moderate sedation.

Table 4.

Odds ratios (ORs) for comparisons of normal physiological and comfort responses across levels of sedation

| Deep vs mild |

Mild vs alert |

Deep vs alert |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Heart rate | 1.619 | 1.586–1.653 | 1.175 | 1.145–1.203 | 1.902 | 1.851–1.954 |

| Oxygen saturation | 1.508 | 1.475–1.543 | 1.110 | 1.081–1.140 | 1.674 | 1.625–1.725 |

| Respiratory rate | 1.362 | 1.338–1.386 | 0.870 | 0.851–0.889 | 1.185 | 1.157–1.213 |

| Actigraphy | ||||||

| Arm | 0.597 | 0.537–0.664 | 0.792 | 0.707–0.887 | 0.473 | 0.413–0.541 |

| Leg | 0.459 | 0.402–0.524 | 0.858 | 0.769–0.957 | 0.394 | 0.341–0.454 |

Discussion

In this prospective study, we determined the relationship among sedation, stable physiological status, and comfort during a 24-hour period in patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Because patients were enrolled at any time during the intubation period, those selected had a median of 2.8 days of intubation before enrollment. Those with a short duration of mechanical ventilation may have been underrepresented. During enrollment, we were also attempting to identify patients who would receive mechanical ventilation for the full 24-hour study period, so patients who were close to their expected extubation time most likely were not selected as often as other patients were. Consequently,the sample consisted of patients with a longer duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU length of stay than is usual at the medical center. These differences may limit generalizability of the findings to patients with a more long-term ICU stay; the results may have greater applicability to patients who have greater needs for sedative therapy and long-term mechanical ventilation.

Level of Sedation

Optimal sedation is the goal for all patients because use of inappropriately high or low levels of sedation in critically ill adults is associated with marked risks and oversedation is a key factor in delayed recovery.8,11,14,43 Guidelines4 of the Society of Critical Care Medicine identify easy arousability and a calm state as the desired level of sedation for most patients receiving mechanical ventilation. However, recent reports2,44 have indicated, similar to our results, that approximately one-third to one-half of patients receiving mechanical ventilation are deeply sedated. Using a variety of sedation scales, Payen et al44 found that 40% to 50% of assessed patients were in a deep state of sedation, and Weinert and Calvin2 found that sedated patients receiving mechanical ventilation were unarousable, minimally arousable, or nonarousable 32% of the time.

Goals for level of sedation are often identified, but sedation orders are generally written with broad parameters to allow for nurses’ discretion.15 In closely monitored clinical trials, patients were at the target level of sedation, on average, only 69% of the time.45 In a recent US survey of nursing sedation practices, Guttormson et al15 found that one-third of the variance in the number of patients who received sedatives was accounted for by nurses’ attitudes. Nurses who thought that mechanical ventilation was uncomfortable and stressful and reported that they would prefer sedation if they were treated with mechanical ventilation were more likely than other nurses to report an intention to sedate patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Nurses’ assessment may also affect sedation level. Weinert and Calvin2 found that although patients were minimally arousable or nonarousable in 32% and motionless in 21% of the sedation assessments, nurses reported that patients were oversedated in less than 3% of cases. In addition, arousal levels and the probability of being judged as oversedated were not related.

Stability of Physiological Status

A primary reason to use sedatives in patients receiving mechanical ventilation is to reduce the physiological stress of respiratory failure and improve the tolerance of invasive life support.2,46,47 Optimally, the goal of a stable physiological status should be achieved regardless of the level of sedation.

Although sedation scales do not generally include evaluation of physiological variables, nurses may include these parameters when determining a patient’s need for sedation and may use traditional normal values as guidelines. In their study of sedation adequacy and characteristics associated with caregivers’ judgment of inadequate sedation, Weinert and Calvin2 found that 70% of nurses agreed that patients are undersedated if the patients are tachypneic and almost half (44%) agreed that patients are undersedated if the patients have elevated heart rate or blood pressure. We found that although a stable physiological status was not achieved at every level of sedation, a stable status did occur more often in deeper levels of sedation. Although this relationship may occur for physiological or pharmacological reasons, using a goal of stable physiological status, especially normal range for heart rate and respiratory rate, nurses may administer more sedative medication until heart rate and respiratory rate are at or near normal levels, potentially resulting in oversedation.

Comfort

Although patients’ comfort is a goal of sedative therapy, measures of comfort in critically ill patients are not standardized. Actigraphy, which we used, provides a measure of limb movement, a surrogate marker of comfort. Patients’ movement is often used in evaluating the adequacy of sedation, and Weinert and Calvin2 found that the kinesiological state of a patient (too much spontaneous activity or too little) had the greatest influence in judgments of the adequacy of sedation. Because the goal is a patient who is easily arousable and calm,4 some spontaneous movement should be expected. However, our data indicate infrequent movement by patients at all levels of sedation. Similarly, in an evaluation of nursing practice, Weinert and Calvin2 found no spontaneous motor activity (during a 10-minute observation period) by patients 21.5% of the time and the level of consciousness or motor activity varied little during a 24-hour period. In addition, in a survey15 of nursing sedation practices, only 17.7% of respondents thought it was easier to care for an awake and alert patient who was receiving mechanical ventilation than to care for a similar patient who was more sedated, and 54.3% strongly disagreed or disagreed with that statement. However, actigraphy is not a clinical measure and is not used in the ICU except as a research measure of movement, a situation that may limit the applicability of our findings directly to the bedside. Nonetheless, early mobilization of patients treated with mechanical ventilation has become more common and is associated with reduced duration of mechanical ventilation,48 reduced hospital length of stay,49 reduced duration of ICU delirium, and enhanced functional status at the time of discharge from the hospital.48 Therefore, lack of movement may not be an appropriate indication of optimal sedation; frequency of spontaneous movement may be more enlightening. Our patients had little activity, but as use of early mobilization increases, actigraphy may become helpful in evaluating this increased level of activity.

Summary

In summary, our data suggest that patients may be sedated more deeply than recommended and that neither a stable physiological status nor comfort (calm state) is uniformly achieved at any sedation level. Tension may exist between nurses’ goals for short-term bedside care of critically ill patients (ie, maintaining deeper levels of sedation on the basis of the nurses’ own attitudes or preferring to care for patients who are not moving) and the long-term detrimental effects of deep sedation. Complete lack of movement should not be accepted as the goal for sedation. However, improvements in sedation management will require specific communication among all care providers and use of clearly identified, measurable definitions of optimal sedation.

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

This research was supported by grant R01 NR009506, National Institute of Nursing Research, to Dr Grap, the principal investigator. Dr Sessler received a speaker’s honorarium from Hospira, Inc, Lake Forest, Illinois.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wunsch H, Kress JP. A new era for sedation in ICU patients. JAMA. 2009;301:542–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinert CR, Calvin AD. Epidemiology of sedation and sedation adequacy for mechanically ventilated patients in a medical and surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:393–401. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254339.18639.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sessler CN, Grap MJ, Brophy GM. Multidisciplinary management of sedation and analgesia in critical care. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;22:211–225. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-13834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobi J, Fraser GL, Coursin DB, et al. Task Force of the American College of Critical Care Medicine (ACCM) of the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), American College of Chest Physicians. Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult [published correction appears in Crit Care Med2002;30(3):726] Crit Care Med. 2002;30:119–141. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sessler CN. Comfort and distress in the ICU: scope of the problem. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;22:111–114. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-13825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbott/American Association of Critical-Care Nurses; Saint Thomas Health System Sedation Expert Panel Members. Consensus conference on sedation assessment: a collaborative venture by Abbott Laboratories, American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, and Saint Thomas Health System. Crit Care Nurse. 2004;24(2):33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kollef MH, Levy NT, Ahrens TS, Schaiff R, Prentice D, Sherman G. The use of continuous i.v. sedation is associated with prolongation of mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1998;114(2):541–548. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.2.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barr J, Donner A. Optimal intravenous dosing strategies for sedatives and analgesics in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 1995;11:827–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nseir S, Makris D, Mathieu D, Durocher A, Marquette CH. Intensive care unit-acquired infection as a side effect of sedation. Crit Care. 2010;14:R30. doi: 10.1186/cc8907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kramer AA, Zimmerman JE. A predictive model for the early identification of patients at risk for a prolonged intensive care unit length of stay. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2010;10:27. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-10-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rello J, Diaz E, Roque M, Valles J. Risk factors for developing pneumonia within 48 hours of intubation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1742–1746. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.6.9808030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1753–1762. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson BJ, Weinert CR, Bury CL, Marinelli WA, Gross CR. Intensive care unit drug use and subsequent quality of life in acute lung injury patients. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3626–3630. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200011000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulain T. Unplanned extubations in the adult intensive care unit: a prospective multicenter study. Association des Réanimateurs du Centre-Ouest. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(4 pt 1):1131–1137. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9702083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guttormson JL, Chlan L, Weinert C, Savik K. Factors influencing nurse sedation practices with mechanically ventilated patients: a US national survey. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2010;26:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sessler CN, Pedram S. Protocolized and target-based sedation and analgesia in the ICU. Crit Care Clin. 2009;25:489–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2009.03.001. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magarey JM. Sedation of adult critically ill ventilated patients in intensive care units: a national survey. Aust Crit Care. 1997;10:90–93. doi: 10.1016/s1036-7314(97)70406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dasta JF, Fuhrman TM, McCandles C. Patterns of prescribing and administering drugs for agitation and pain in patients in a surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:974–980. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199406000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egerod I. Uncertain terms of sedation in ICU. How nurses and physicians manage and describe sedation for mechanically ventilated patients. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11:831–840. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arias-Rivera S, Sanchez-Sanchez MM, Santos-Diaz R, et al. Effect of a nursing-implemented sedation protocol on weaning outcome. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2054–2060. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817bfd60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quenot JP, Ladoire S, Devoucoux F, et al. Effect of a nurse-implemented sedation protocol on the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2031–2036. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000282733.83089.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arabi Y, Haddad S, Hawes R, et al. Changing sedation practices in the intensive care unit—protocol implementation, multifaceted multidisciplinary approach and teamwork. Middle East J Anesthesiol. 2007;19(2):429–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brook AD, Ahrens TS, Schaiff R, et al. Effect of a nursing-implemented sedation protocol on the duration of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2609–2615. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199912000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marx WH, DeMaintenon NL, Mooney KF, et al. Cost reduction and outcome improvement in the intensive care unit. J Trauma. 1999;46:625–629. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199904000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ibrahim EH, Kollef MH. Using protocols to improve the outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients: focus on weaning and sedation. Crit Care Clin. 2001;17:989–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grap MJ, Blecha T, Munro C. A description of patients’ report of endotracheal tube discomfort. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2002;18:244–249. doi: 10.1016/s0964339702000654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prichep LS, Gugino LD, John ER, et al. The Patient State Index as an indicator of the level of hypnosis under general anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92:393–399. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen X, Tang J, White PF, et al. A comparison of Patient State Index and bispectral index values during the perioperative period. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:1669–1674. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200212000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider G, Heglmeier S, Schneider J, Tempel G, Kochs EF. Patient State Index (PSI) measures depth of sedation in intensive care patients. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:213–216. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurup V, Ramani R, Atanassoff PG. Sedation after spinal anesthesia in elderly patients: a preliminary observational study with the PSA-4000. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:562–565. doi: 10.1007/BF03018398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drover D, Ortega HR. Patient State Index. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2006;20:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramsay MA, Huddleston P, Henry C, Marcel R, Tai S. The Patient State Index is an indicator of inadequate pain management in the unresponsive ICU patient [abstract] Anesthesiology. 2004;101:A349. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grap MJ, Borchers CT, Munro CL, Elswick RK, Jr., Sessler CN. Actigraphy in the critically ill: correlation with activity, agitation, and sedation. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14:52–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mistraletti G, Taverna M, Sabbatini G, et al. Actigraphic monitoring in critically ill patients: preliminary results toward an “observation-guided sedation.”. J Crit Care. 2009;24:563–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grap MJ, Hamilton VA, McNallen A, et al. Actigraphy: analyzing patient movement. Heart Lung. 2011;40(3):e52–e59. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, et al. The APACHE III prognostic system: risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1991;100:1619–1636. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.6.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knaus WA, Zimmerman JE, Wagner DP. APACHE—Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation: a physiologically based classification system. Crit Care Med. 1981;9:591–597. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198108000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giangiuliani G, Mancini A, Gui D. Validation of a severity of illness score (APACHE II) in a surgical intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 1989;15:519–522. doi: 10.1007/BF00273563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montgomery AB, Stager MA, Carrico CJ, Hudson LD. Causes of mortality in patients with the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132:485–489. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.132.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roger-Moreau I, de Barbeyrac B, Ducoudre M, et al. Evaluation of bronchoalveolar lavage for the diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia in ventilated patients. Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 1992;50(8):587–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacobs S, Chang RW, Lee B, Bartlett FW. Continuous enteral feeding: a major cause of pneumonia among ventilated intensive care unit patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1990;14(4):353–356. doi: 10.1177/0148607190014004353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sessler CN, Kollef MH, Hamilton A, Grap MJ, Jefferson D. Comparison of depth of sedation measured by PSA 4000 and Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) [abstract] Chest. 2005;128(4):151S–152S. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salluh JI, Soares M, Teles JM, et al. Delirium epidemiology in critical care (DECCA): an international study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R210. doi: 10.1186/cc9333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Payen JF, Chanques G, Mantz J, et al. Current practices in sedation and analgesia for mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a prospective multicenter patient-based study. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(4):687–695. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264747.09017.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ostermann ME, Keenan SP, Seiferling RA, Sibbald WJ. Sedation in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. JAMA. 2000;283:1451–1459. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.11.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weinert CR, Chlan L, Gross C. Sedating critically ill patients: factors affecting nurses’ delivery of sedative therapy. Am J Crit Care. 2001;10:156–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rhoney DH, Murry KR. National survey of the use of sedating drugs, neuromuscular blocking agents, and reversal agents in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2003;18:139–145. doi: 10.1177/0885066603251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874–1882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morris PE, Goad A, Thompson C, et al. Early intensive care unit mobility therapy in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2238–2243. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180b90e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]