Abstract

Object

Our previous studies found that simvastatin treatment of traumatic brain injury (TBI) in rats had beneficial effects on spatial learning functions. In the current study we wanted to determine whether simvastatin suppressed neuronal cell apoptosis after TBI, and if so, the underlying mechanisms of this process.

Methods

Saline or simvastatin (1 mg/kg) was administered orally to rats starting at Day 1 after TBI and then daily for 14 days. Modified neurological severity scores (NSS) were employed to evaluate the sensory motor functional recovery. Rats were sacrificed at 1, 3, 7, 14 and 35 days after treatment and brain tissue was harvested for TUNEL staining, caspase-3 activity assay and Western blot analysis. Simvastatin significantly decreased NSS from Days 7 to 35 after TBI, significantly reduced the number of TUNEL-positive cells at Day 3, suppressed the caspase-3 activity at Days 1 and 3 after TBI, and increased phosphorylation of Akt as well as FOXO1, IκB and eNOS, which are the downstream targets of the pro-survival Akt signaling protein.

Conclusions

These data suggested that simvastatin reduces the apoptosis in neuronal cells and improves the sensory motor function recovery after TBI. These beneficial effects of simvastatin may be mediated through activation of Akt, FOXO1 and NF-κB signaling pathways, which suppress the activation of caspase-3 and apoptotic cell death, and thereby lead to neuronal function recovery after TBI.

Keywords: simvastatin, apoptosis, Akt, FOXO1, IκB, traumatic brain injury

INTRODUCTION

Simvastatin is a member of the HMG-CoA reductase family of drugs and has recently been described as promoting therapeutic benefit in pathologies other than hyperlipidemia.2 Our previous studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of simvastatin on functional recovery and neurogenesis after traumatic brain injury (TBI) in rats.19,20 Statins increase synaptogenesis following neuronal hypoxia in a model of ischemic stroke3 as well as increase vascular endothelial growth factor, improve cerebral blood flow and enhance brain plasticity.31 Chronic simvastatin treatment has been shown to be neuroprotective both in vivo 14 and in vitro.35 While the numerous, non-cholesterol-related benefits of simvastatin have been identified, the mechanism underlying these effects has not been well defined. This is particularly true in the area of statin-induced neuroprotection, where simply lowering cholesterol levels does not appear to be the sole regulator of neuroprotection.

The phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling pathway plays a crucial role in cell growth and cell survival. Activated Akt phosphorylates several downstream signaling target proteins, including Bad, GSK3-β, Forkhead (FOXO) transcription factors and IκB to control cell growth, cell survival, and protein synthesis. FOXOs regulate the transcription of the cell cycle inhibitor p27 as well as the pro-apoptotic Fas ligand and the Bcl-2-like-protein Bim.12 Phosphorylation of IκB leads to its dissociation and activation of NF-κB, which induces the expression of several genes that promote neuron survival, including those encoding manganese superoxide dismutase, inhibitor-of-apoptosis (IAP) proteins, Akt, Bcl-2, and calbindin.23

In this study, we investigate the effects of simvastatin on apoptotic cell death after TBI. To examine a possible mechanism for the neuroprotective effects of simvastatin which subsequently enhanced the functional recovery, we focused on the Akt pathway, which has been implicated in the survival of neuronal cells.32

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Models

In the present study we used a modified controlled cortical injury (CCI) model of TBI in rats.22 All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Henry Ford Hospital.

Adult male Wistar rats weighing 300 to 400 g were anesthetized intraperitoneally with 350 mg/kg body weight chloral hydrate. Rectal temperature was maintained at 37°C by using a feedback-regulated water heating pad. A CCI device was used to induce injury. Rats were placed in a stereotactic frame. Two 10-mm diameter craniotomies were performed adjacent to the central suture, midway between the lambda and the bregma. The second craniotomy allowed for lateral movement of cortical tissue. The dura mater was kept intact over the cortex. Injury was induced by striking the left cortex (ipsilateral cortex) with a pneumatic piston containing a 6-mm diameter tip at a rate of 4 m/second and exerting 2.5 mm of compression. Velocity was measured using a linear velocity displacement transducer. Sham injured animals were similarly anesthetized and craniectomy performed without cortical injury.

Experimental Groups

Male Wistar rats were randomly divided into three groups. Rats in the first group (n = 40) were exposed to TBI and given saline orally 1 day later and consecutively for 14 days. Rats in the second group (n = 40) were subjected to TBI, and 1 day later simvastatin was administered orally at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day for 14 consecutive days. This dose was selected based on our previously reported study.20 Rats in the third group (n = 8) were subjected to sham surgery. Neurological functional evaluation was performed on Days 1, 3, 7, 14 and 35 after TBI. Rats in the first and second groups were sacrificed at 1, 3, 7, 14 and 35 days after administration of simvastatin, and rats in the sham group were sacrificed at 1 day after TBI. Sixteen animals were sacrificed at each time point; 8 rats were used for immunohistochemistry and the other 8 rats for Western blot analysis.

Neurological Functional Evaluation

Neurological functional measurement was performed using a modified Neurological Severity Score (mNSS). The mNSS is a composite of the motor (muscle status, abnormal movement), sensory (visual, tactile and proprioceptive) and reflex tests. This test has been employed in previous studies.6, 19 Motor tests of the mNSS include seven items with a maximum of 6 points. Sensory tests include two items with a maximum score of 2. Beam Balance Tests have seven items with a maximum score of 6. The last part of the mNSS includes the pinna, corneal and startle reflexes and abnormal movements. Insult in the left hemisphere cortex of rats causes sensory and motor functional deficiency with elevated scores early after TBI.21

Tissue Preparation

For immunostaining, rats were anesthetized intraperitoneally with chloral hydrate (350 mg/kg), and perfused transcardially with saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were isolated, post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 days at room temperature, and then processed for paraffin sectioning. A series of 10-µm thick sections were cut with a microtome through each of seven standard sections. For biochemical analysis, the ipsilateral and contralateral cortex and hippocampus tissues were dissected, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use.

TUNEL Staining

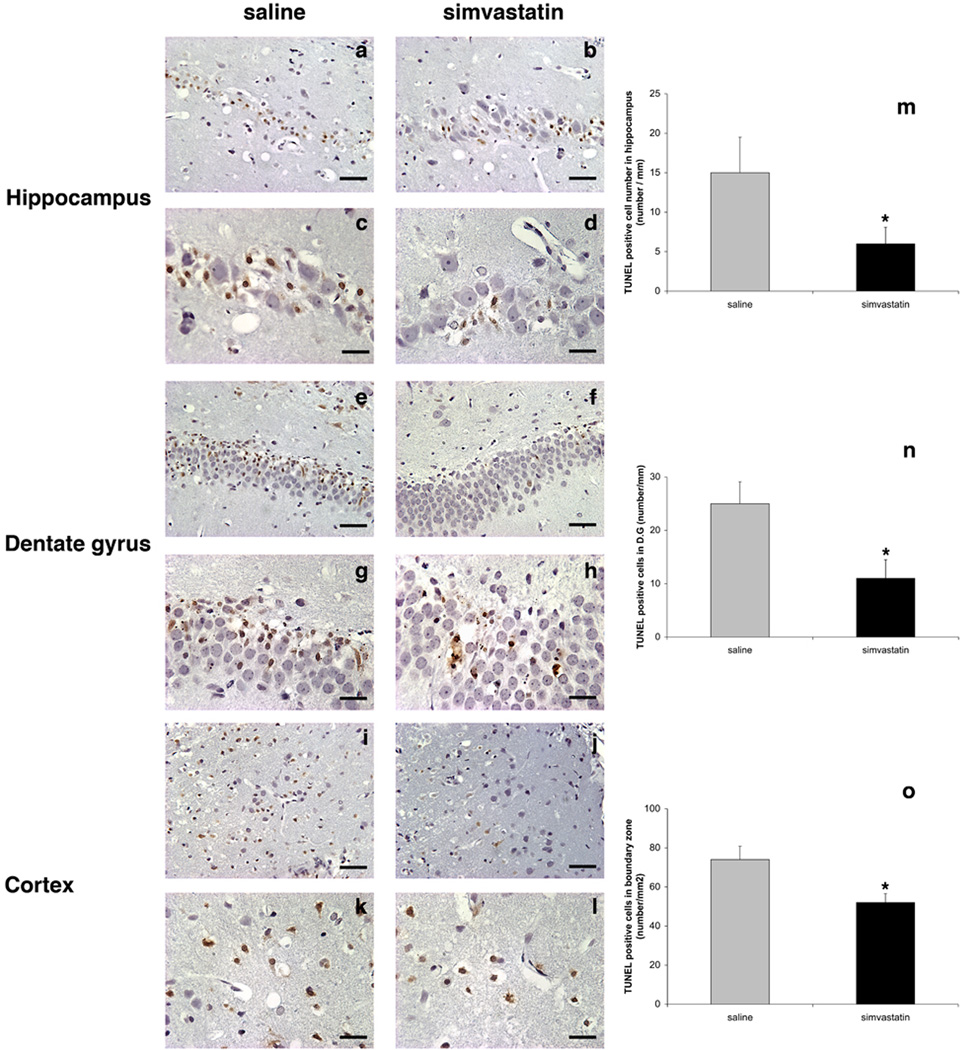

To identify cellular apoptosis, terminal deoxynucleotidyl nick-end labeling (TUNEL) was performed using an ApopTag peoroxidase in situ apoptosis detection Kit (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). The paraffin-embedded coronal sections at the level of the hippocampus and DG were selected and processed for TUNEL staining. After the digesting and quenching steps, equilibration buffer was applied directly to the sections and working-strength TdT enzyme was then applied directly. A biotin-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody was used. The sections were then incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody at 1:100 dilution for 45 minutes at room temperature and later with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled streptavidin at 1:100 dilution for 45 minutes at room temperature. After a brief wash, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (0.5 mg/mL)/H2O2 (0.01%), a chromogen substrate, was incorporated. To quantify apoptotic neuronal cells in different areas, 10 consecutive fields were randomly selected and evaluated at 400 X using an imaging analyzer. A blind counting methodology was employed to count TUNEL-positive cell numbers. For counting, images were obtained from the cortex, hippocampus and DG of the ipsilateral side of the injured animals. In each image we then counted manually the TUNEL-positive cells from the boundary zone in cortex, the CA3 region in hippocampus, and the body and hilus of the DG. Total cell counts are depicted in the histogram of Figure2, panel m~n.

Fig. 2.

TUNEL staining for detection of the apoptotic cells. Representative pictures show the TUNEL-positive staining cells (brown) in the cortex, dentate gyrus and hippocampus CA1 area (a~l). Plots (m~o) show the statistical analysis of TUNEL-positive cell number in these areas. Treatment with simvastatin decreases the number of TUNEL-positive cells compared to saline. Scale bar = 50 µm (a,b,e,f,i,j), 100 µm (c,d,g,h,k,l). Data are represented as mean ± SD. * p < 0.05, n = 4/group.

Caspase-3 Activity Assay

The activity of caspase-3 was determined using an Apo-Alert colorimetric caspase-3 assay kit (BD Biosciences Clontech). Brain cortex tissues in the boundary zone were collected and lysed in lysis buffer and equal amounts of lysates were used for caspase-3 activity assay, which was measured at a wavelength of 405 nm using the detection of chromophore p-nitroaniline (pNA) after its cleavage by caspase-3 from the labeled caspase-3 specific substrate, DEVD-pNA. The data are presented as pmoles of pNA per microgram of cell lysate per hour of incubation.

Western Blot Analysis

Rats in Groups 1 and 2 were sacrificed at Days 1, 3, 7, 14 and 35 after administration of simvastatin (n = 4 per time point per group). Brain tissues from the lesion boundary zone and the hippocampus were collected, washed once in 1× PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, 1% deoxycholic acid, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaVO3, 50 mM NaF, cocktail I of protease inhibitors from Calbiochem). After sonication, soluble protein was obtained by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The protein concentration of each sample was determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). For immunoblotting, equal amounts of cell lysate were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide electrophoresis on Novex Tris-Glycine pre-cast gels (Invitrogen) and separated proteins were then electrotransferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were blocked with 2% I-Block (Applied Biosystem) in PBS plus 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 hour at room temperature and then incubated with different primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. We used the following antibodies: anti-p-eNOS (Ser1177), anti-p-FOXO1 (Ser 256) and anti-p-IκB (Ser32) (1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); anti-p-Akt (Ser473), anti-Actin (I-19) (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). After washing, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2500; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) in blocking buffer for 2 hours at room temperature. Specific proteins were visualized using SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence substrate system (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The intensity of the bands was measured using Scion image analysis (Scion Corperation, Frederick, MD).

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Data were analyzed by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences were determined to be significant with p < 0.05. All measurements were performed by observers blinded to individual treatments.

RESULTS

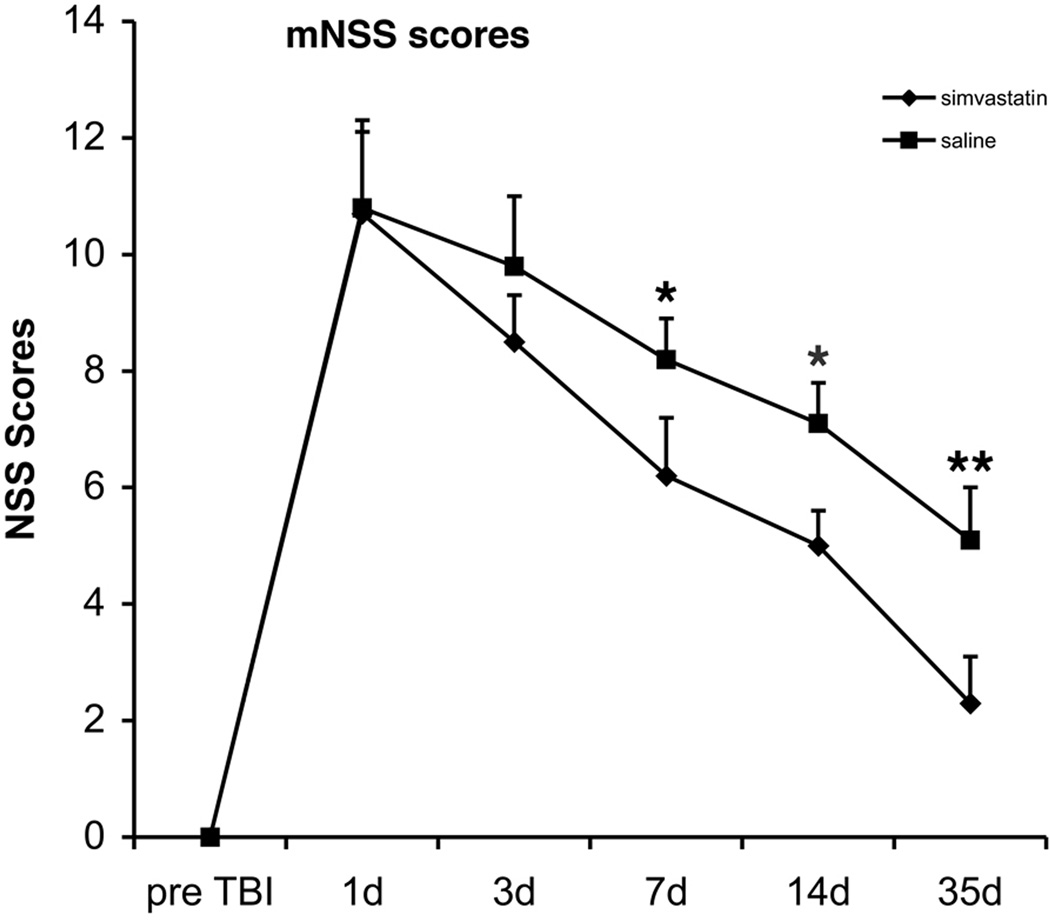

Simvastatin enhances the recovery of sensory-motor function after TBI

Injury in the left hemisphere cortex of rats causes neurological functional deficits as measured by mNSS (Fig. 1). These rats presented with high scores on motor, sensory and Beam Balance Tests on Day 1 after injury. Absent reflexes and abnormal movements were evident in rats with severe injury. On Day 3 after injury, recovery began, and this recovery persisted at all subsequent evaluation time points in both saline-treated and simvastatin-treated groups. Motor function tested by the mNSS recovered faster than sensory and beam balance functions. By Day 14 after injury, residual deficit scores were present mainly on the Beam Balance Tests and sensory (placing) test of the mNSS. The mNSS scores for the simvastatin-treated group were significantly decreased at Days 7 and 14 (6.2 ± 1.2 and 5.0 ± 0.6, respectively, p < 0.05) after TBI when compared with the saline-treated groups (8.2 ± 0.9 and 7.1 ± 0.7, respectively, p < 0.05) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The temporal profile of the NSS after TBI in saline- or simvastatin-treated rats. The score was significantly decreased in the simvastatin-treated group compared to the saline group from 7 days after treatment. These data demonstrate that simvastatin enhances the sensory-motor functional recovery after TBI. Data are represented as mean ± SD. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, n = 8.

Simvastatin reduces TUNEL-positive cells

TUNEL staining has been used extensively to identify cells with nuclear DNA fragmentation.29 Cells were scored as apoptotic when they were TUNEL-positive (brown staining) (Fig. 2a~l) and showed nuclear chromatin condensation (arrows in Figure 2a). In each hemispheric section of the sham-operated rats and in the contralateral hemisphere of ischemic rats, cells were almost negative for TUNEL staining, with only zero to three TUNEL-positive cells. Those cells with nuclei not stained with TUNEL (TUNEL-negative, blue-colored) were visualized by counterstaining with hematoxylin. In contrast, in the ipsilateral hemisphere in the saline control group, a large number of TUNEL-positive cells, which were mainly located in the ipsilateral boundary cortex, hippocampus and DG, were seen at 24 hours after TBI. Simvastatin reduced the number of TUNEL-positive cells (74 ± 6.8 vs 52 ± 4.6 in the lesion boundary zone, p < 0.05, 15 ± 4.5 vs 6 ± 2.1 in the hippocampus, p < 0.01) as compared to the saline-treated group notable in day 3 after treatment (Figure 2 a~l), demonstrating that simvastatin reduces apoptosis in the hippocampus and the lesion boundary zone after TBI.

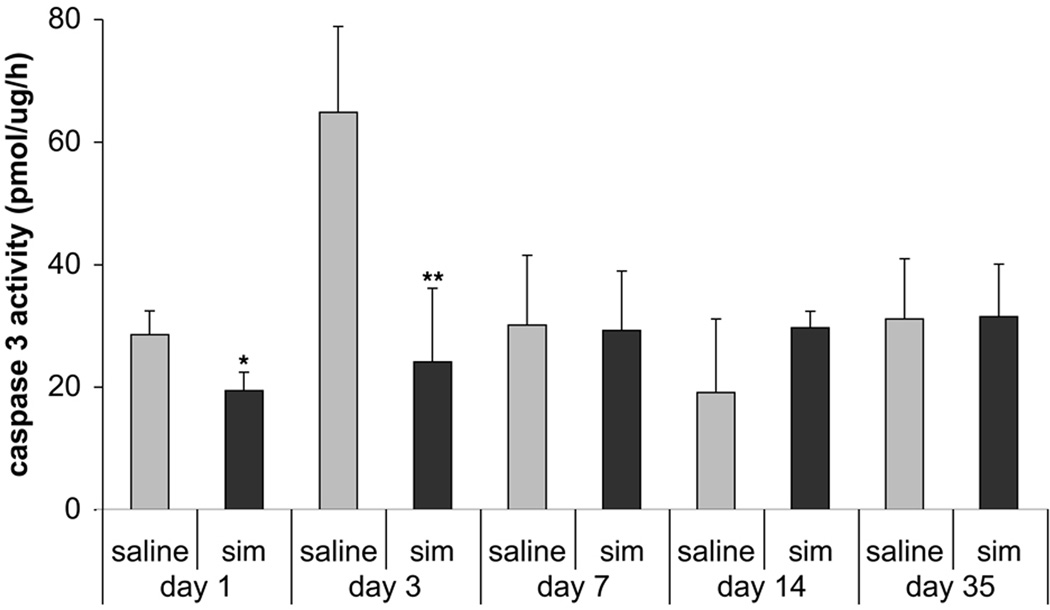

Simvastatin reduces apoptotic cell death through suppression of caspase-3 activity

Caspase-3 activity was measured to determine if simvastatin suppressed the TBI-induced apoptosis via the caspase cascade, which is the central protease in the cell death pathway. Colorimetric assay showed a significant decrease in caspase-3 activity at Days 1 (28.56 ± 3.9 vs 19.45 ± 2.9, p < 0.05) and 3 (64.86 ± 13.98 vs 24.15 ± 12.01, p < 0.01) after simvastatin treatment (Fig. 3), suggesting simvastatin suppresses the cleavage of caspase-3.

Fig. 3.

Bar graphs show the activity of caspase-3. Simvastatin decreases the activity of caspase-3 at Days 1 and 3 after treatment compared to the saline group. As caspase-3 plays a key role in the process of cell apoptosis, inhibition of caspase-3 activity may result in suppression of apoptosis after TBI. Data are represented as mean ± SD. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. saline group, n = 4.

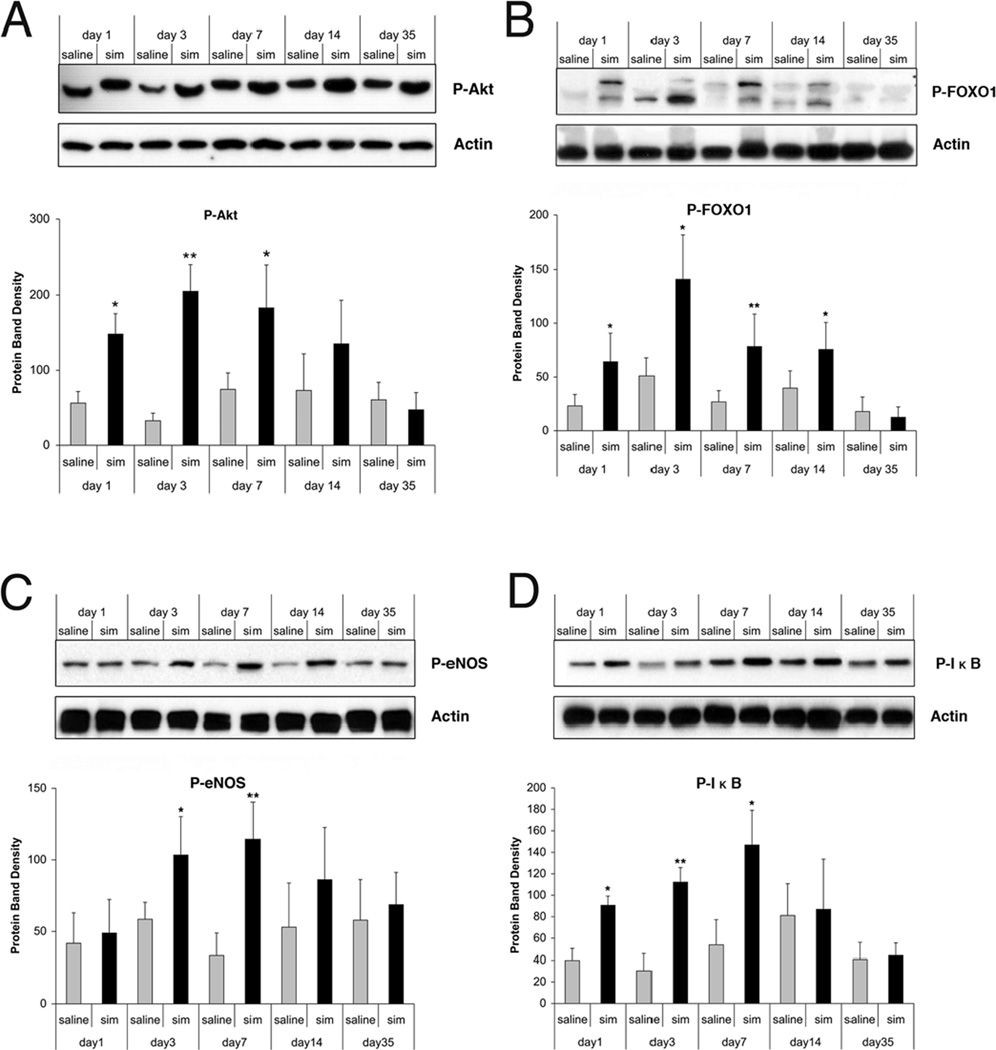

Phosphorylation of Akt, eNOS, FOXO-1 and IκB in the ipsilateral hemisphere upon treatment with simvastatin after TBI

We have previously shown that simvastatin significantly enhanced the phosphorylation of Akt at Day 1 upon treatment, which was sustained until Day 7, with a peak at Day 3 (Fig. 4a). Therefore, we investigated whether simvastatin may phosphorylate and thereby activate/inactivate its downstream targets, such as FOXOs. Our data show that the phosphorylation of FOXO1 was increased in the simvastatin-treated group, which began at Day 1 and lasted to Day 7 after treatment (Fig. 4b). Akt-dependent phosphorylation leads to the posttranslational activation of eNOS via phosphorylation of the amino acid Ser1177, which has been described as an important anti-apoptotic signaling pathway in endothelial cells.33 Western blot analysis showed a substantial increase of p-eNOS in the ipsilateral hemisphere after TBI, which has been described as an important anti-apoptotic signaling pathway in endothelial cells. The levels of p-eNOS were significantly increased at Day 3 after simvastatin treatment (Fig. 4c) (p < 0.05 at Day 3), remaining elevated at Day 7 (p < 0.01 at Day 7) and then declined to control level at Day 14. Because phosphorylation of IκB-α at Ser32 is essential for release of active NF-κB, phosphorylation at this site is an excellent marker of NF-κB activation. Western blot analysis showed an elevated phosphorylation of IκB-α at Ser32 from Days 1 to 7 after TBI (p < 0.05 at Days 1, 3 and 7).

Fig. 4.

Representative Western blot and densitometry measurement of a) p-FOXO1, b) p-eNOS, and c) p-IκB in the cortex in rats treated with simvastatin (black bars) or saline (grey bars) after TBI (AU = arbitrary units). Data in the bar graphs are represented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05. Simvastatin treatment significantly increases FOXO1 phosphorylation from Days 1 to 14 after treatment, eNOS phosphorylation at Days 3 and 7, and IκB phosphorylation at Days 3, 7 and 14. As FOXO1 and IκB are key factors of anti-apoptotic Akt signaling pathway, these data indicate simvastatin may reduce the neuronal cell apoptosis via activation of the above signaling factors.

DISCUSSION

The primary findings in the present study are: 1) Treatment of TBI with simvastatin promotes the restoration of sensory motor function; 2) Simvastatin suppresses activation of caspase-3 and protects the cells from apoptosis; and 3) Simvastatin induces phosphorylation of Akt along with activation of the anti-apoptotic IκB and eNOS, and inactivation of the pro-apoptotic FOXOs.

In the controlled cortical impact model of TBI, delayed neuronal cell death occurs in the boundary zone of the injured cortical area and the CA3 region of the hippocampus, in addition to the primary neuronal necrosis normally seen after injury.15,24 Both patterns of neuronal cell death may cause certain neuronal loss in these areas and subsequent neurological functional deficits in the animals.11 These areas are potentially salvageable. Rescuing the damaged neurons in these areas promotes functional outcome after brain injury.16 Therefore, neuronal survival in these areas is an important target to evaluate the degree of damaged brain tissue and the effect of therapeutic intervention.25 In our current study, significant functional improvements in the simvastatin-treated group were detected by the mNSS at Days 7 and 14 after treatment when compared with saline-treated control group. Significant functional improvement occurring at Day 7 after treatment suggests that simvastatin may rescue damaged neurons. This hypothesis was supported by the decreased numbers of TUNEL-positive cells in the boundary zone and the hippocampus in the ipsilateral hemisphere after simvastatin treatment (Fig. 3).

To address the potential mechanisms by which simvastatin exerts its protective effects, we analyzed the caspase-3 activity in tissue samples obtained from different time points. Caspases, the ICE/CED-3 family of proteases, play a central role in the early stages of apoptosis. Of the identified caspases, caspase-3 is activated during apoptosis in many types of central nervous system cells, and its activation appears to be an important event in apoptosis.28 Previous studies have shown increased apoptosis and caspase-3 activity in a rat TBI model.7,34 Simvastatin significantly decreased caspase-3 activities on Days 1 and 3 after treatment, suggesting that simvastatin inhibits the caspase-3 activation in the early phase. These results are consistent with previous data on the effect of simvastatin on caspase-3 activity in a hypoxia-ischemia model in the newborn rat.5

As simvastatin may prevent apoptotic cell death through inhibition of caspase-3 activation, we further explored its underlying signaling pathway. The effect of simvastatin on phosphorylation of Akt has been reported in endothelial cells in vitro.18 Recent studies suggest that simvastatin induces the phosphorylation of Akt 6,17 in the context of ischemic injury, which has also been confirmed in our previous study in a TBI model. Therefore, we tested the effect of simvastatin treatment on phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream targets eNOS, IκB and FOXO1. Western blot analysis shows that simvastatin induces the phosphorylation of Akt, eNOS, IκB and FOXO1.

Because Akt phosphorylates FOXOs as downstream targets in cell survival signaling,4,30 we examined changes in FOXO1 phosphorylation as well as Akt phosphorylation after TBI. FOXOs regulate the transcription of the cell cycle inhibitor p27 and the Bcl-2-like-protein Bim, both of which are strong pro-apoptotic signaling proteins.27 Akt phosphorylates and inactivates FOXO1 which prevents its translocation to the nucleus, thereby inhibiting apoptotic signaling.30 FOXO1 in neurons normally stays in the cytoplasm because of Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Once Akt activity is reduced by brain injury conditions, FOXO1 is dephosphorylated by undefined protein phosphatases. The dephosphorylation contributes to their nuclear import through nuclear localization signals. DNA-binding domain is required for activation of the promoters of Fas-ligand and Bim genes.8,12 Expression of the Fas-ligand gene induces caspase activation which eventually leads to apoptosis. Simvastatin significantly increases phosphorylation of FOXO1 at an early phase in an Akt-dependent manner, and thereby, likely rescues neurons from apoptosis through phosphorylation and inactivation of FOXO1.

NF-κB is widely known for its ubiquitous roles in the immune response, as well as in control of cell division and apoptosis.1 Functional NF-κB complexes are present in essentially all cell types in the nervous system, including neurons.26 NF-κB in its inactive form is present in cytosol as a three-subunit complex, with the prototypical components being p65 and p50 and IκB (inhibitory subunit). NF-κB is activated by signals that activate IκB kinase (IKK), resulting in phosphorylation of IκB; this targets IκB for degradation in the proteosome and frees the p65-p50 dimer, which then translocates to the nucleus and binds to consensus κB sequences in the promoter region of κB-responsive genes. NF-κB induces the expression of several different genes that promote neuron survival, including those encoding manganese superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD), inhibitor-of-apoptosis proteins (IAPs), and Bcl-2. These pro-survival proteins prevent the injured cells from undergoing the apoptotic process. Levels of NF-κB activity are increased in cerebral cortex within hours of TBI in rats, after which they remain elevated for at least 24 hours.23 Our data show that simvastatin elevates phosphorylation of IκB, which has been proven to promote the activation of NF-κB.26 The elevated phosphorylation of IκB lasts for 7 days after simvastatin treatment, inducing a prolonged activation of NF-κB, which may mediate the anti-apoptotic effect of simvastatin.

Akt-dependent phosphorylation leads to the posttranslational activation of the eNOS via phosphorylation of the amino acid Ser1177, which has been described as an important anti-apoptotic signaling pathway in endothelial cells.9,13,36 Upregulated expression of eNOS leads to an increase in cerebral blood flow, smaller cerebral infarcts, and decreased neurological deficits in stroke.10 Recent studies suggest that simvastatin can rapidly activate the protein kinase Akt/PKB in endothelial cells. Accordingly, simvastatin enhances phosphorylation of the endogenous Akt substrate eNOS and inhibits apoptosis in vitro in an Akt-dependent manner.18 In the TBI model, we find a similar pattern of elevated phosphorylation of eNOS after treatment with simvastatin.

Based on our findings we propose that treatment with simvastatin increases phosphorylation of Akt in the neuronal cells after TBI, followed by phosphorylation of its downstream targets FOXO, IκB and eNOS, which eventually leads to anti-apoptotic effects partially through suppressing caspase 3 activity.

In summary, our data suggest that simvastatin suppresses apoptosis of neuronal cells and enhances the sensory-motor functional recovery post TBI. The Akt/FOXO1/IκB/caspase-3 pathway may play a vital role in the neuroprotective effect of simvastatin treatment after TBI.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01NS052280-01A1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balduini W, De Angelis V, Mazzoni E, Cimino M. Simvastatin protects against long-lasting behavioral and morphological consequences of neonatal hypoxic/ischemic brain injury. Stroke. 2001;32:2185–2191. doi: 10.1161/hs0901.094287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balduini W, Mazzoni E, Carloni S, De Simoni MG, Perego C, Sironi L, et al. Prophylactic but not delayed administration of simvastatin protects against long-lasting cognitive and morphological consequences of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, reduces interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha mRNA induction, and does not affect endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression. Stroke. 2003;34:2007–2012. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000080677.24419.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunet A, Park J, Tran H, Hu LS, Hemmings BA, Greenberg ME. Protein kinase SGK mediates survival signals by phosphorylating the forkhead transcription factor FKHRL1 (FOXO3a) Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:952–965. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.952-965.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carloni S, Mazzoni E, Cimino M, De Simoni MG, Perego C, Scopa C, et al. Simvastatin reduces caspase-3 activation and inflammatory markers induced by hypoxia-ischemia in the newborn rat. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;21:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Zhang ZG, Li Y, Wang Y, Wang L, Jiang H, et al. Statins induce angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and synaptogenesis after stroke. Ann. Neurol. 2003;53:743–751. doi: 10.1002/ana.10555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark RS, Kochanek PM, Watkins SC, Chen M, Dixon CE, Seidberg NA, et al. Caspase-3 mediated neuronal death after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurochem. 2000;74:740–753. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.740740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dijkers PF, Medema RH, Lammers JW, Koenderman L, Coffer PJ. Expression of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bim is regulated by the forkhead transcription factor FKHR-L1. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1201–1204. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00728-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Nitric oxide-an endothelial cell survival factor. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:964–968. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endres M, Laufs U, Huang Z, Nakamura T, Huang P, Moskowitz MA, et al. Stroke protection by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA reductase inhibitors mediated by endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8880–8885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox GB, Fan L, Levasseur RA, Faden AI. Sustained sensory/motor and cognitive deficits with neuronal apoptosis following controlled cortical impact brain injury in the mouse. J Neurotrauma. 1998;15:599–614. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukunaga K, Ishigami T, Kawano T. Transcriptional regulation of neuronal genes and its effect on neural functions: expression and function of forkhead transcription factors in neurons. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;98:205–211. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fmj05001x3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho FM, Lin WW, Chen BC, Chao CM, Yang CR, Lin LY, et al. High glucose-induced apoptosis in human vascular endothelial cells is mediated through NF-kappaB and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase pathway and prevented by PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway. Cell Signal. 2006;18:391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jick H, Zornberg GL, Jick SS, Seshadri S, Drachman DA. Statins and the risk of dementia. Lancet. 2000;356:1627–1631. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaya SS, Mahmood A, Li Y, Yavuz E, Goksel M, Chopp M. Apoptosis and expression of p53 response proteins and cyclin D1 after cortical impact in rat brain. Brain Res. 1999;818:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kermer P, Klocker N, Bahr M. Neuronal death after brain injury. Models, mechanisms, and therapeutic strategies in vivo. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;298:383–395. doi: 10.1007/s004410050061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kretz A, Schmeer C, Tausch S, Isenmann S. Simvastatin promotes heat shock protein 27 expression and Akt activation in the rat retina and protects axotomized retinal ganglion cells in vivo. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006;21:421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kureishi Y, Luo Z, Shiojima I, Bialik A, Fulton D, Lefer DJ, et al. The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin activates the protein kinase Akt and promotes angiogenesis in normocholesterolemic animals. Nat Med. 2000;6:1004–1010. doi: 10.1038/79510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu D, Goussev A, Chen J, Pannu P, Li Y, Mahmood A, et al. Atorvastatin reduces neurological deficit and increases synaptogenesis, angiogenesis, and neuronal survival in rats subjected to traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:21–32. doi: 10.1089/089771504772695913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu D, Qu C, Goussev A, Jiang H, Lu C, Schallert T, et al. Statins increase neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus, reduce delayed neuronal death in the hippocampal CA3 region, and improve spatial learning in rat after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1132–1146. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu D, Sanberg PR, Mahmood A, Li Y, Wang L, Sanchez-Ramos J, et al. Intravenous administration of human umbilical cord blood reduces neurological deficit in the rat after traumatic brain injury. Cell Transplant. 2002;11:275–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahmood A, Lu D, Wang L, Chopp M. Intracerebral transplantation of marrow stromal cells cultured with neurotrophic factors promotes functional recovery in adult rats subjected to traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2002;19:1609–1617. doi: 10.1089/089771502762300265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattson MP, Camandola S. NF-kappaB in neuronal plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:247–254. doi: 10.1172/JCI11916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McIntosh TK, Juhler M, Wieloch T. Novel pharmacologic strategies in the treatment of experimental traumatic brain injury: 1998. J Neurotrauma. 1998;15:731–769. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murohara T, Asahara T. Nitric oxide and angiogenesis in cardiovascular disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4:825–831. doi: 10.1089/152308602760598981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Neill LA, Kaltschmidt C. NF-kappa B: a crucial transcription factor for glial and neuronal cell function. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:252–258. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rena G, Guo S, Cichy SC, Unterman TG, Cohen P. Phosphorylation of the transcription factor forkhead family member FKHR by protein kinase B. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17179–17183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robertson GS, Crocker SJ, Nicholson DW, Schulz JB. Neuroprotection by the inhibition of apoptosis. Brain Pathol. 2000;10:283–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2000.tb00262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saraste A, Pulkki K. Morphologic and biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;45:528–537. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang ED, Nunez G, Barr FG, Guan KL. Negative regulation of the forkhead transcription factor FKHR by Akt. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16741–16746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaughan CJ, Delanty N, Basson CT. Statin therapy and stroke prevention. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2001;16:219–224. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200107000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang L, Gang Zhang Z, Lan Zhang R, Chopp M. Activation of the PI3-K/Akt pathway mediates cGMP enhanced-neurogenesis in the adult progenitor cells derived from the subventricular zone. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1150–1158. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolfrum S, Dendorfer A, Schutt M, Weidtmann B, Heep A, Tempel K, et al. Simvastatin acutely reduces myocardial reperfusion injury in vivo by activating the phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44:348–355. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000137162.14735.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yakovlev AG, Knoblach SM, Fan L, Fox GB, Goodnight R, Faden AI. Activation of CPP32-like caspases contributes to neuronal apoptosis and neurological dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7415–7424. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07415.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zacco A, Togo J, Spence K, Ellis A, Lloyd D, Furlong S, et al. 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors protect cortical neurons from excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11104–11111. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11104.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang W, Wang R, Han SF, Bu L, Wang SW, Ma H, et al. alpha-Linolenic acid attenuates high glucose-induced apoptosis in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells via PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway. Nutrition. 2007;23:762–770. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]