Abstract

The strength of a synapse can profoundly influence network function. How this strength is set at the molecular level is a key question in neuroscience. Here we review a simple model of neurotransmission that serves as a convenient framework to discuss recent studies on RIM and synaptotagmin.

The basics of synaptic transmission

Most neurons in the mammalian central nervous system are connected by chemical synapses. These specialized structures do not simply transmit a sequence of action potentials (APs) from one cell to the next, but can act as filters to modify signals (1). For example, connections that are strong (like the climbing fiber synapse of the cerebellum) reliably transmit individual, isolated APs yet depress in response to trains where the same stimuli are delivered at high frequency. On the other hand, synapses that are initially weak (like the parallel fiber of the cerebellum) tend to facilitate, giving a larger response per stimulus if APs are delivered in bursts. These examples illustrate how strong synapses can function as low pass filters and weak synapses can operate as high pass filters, influencing how information flows through neural circuits (1). In addition to these relatively rapid effects (on the order of seconds), activity dependent presynaptic changes can occur on longer timescales (hours or longer) and lead to enduring modifications of network properties (35). Thus, what determines a synapse’s strength at the molecular level is a key question that has important implications for circuit function. Here we review a simple model of neurotransmitter release that serves as a framework to discuss potential influences on synaptic strength. We then discuss recent examples from work on molecules that control the efficacy of synaptic transmission.

Before addressing neurotransmitter release, it is worth briefly reviewing the anatomy of the structure involved, as determined from three-dimensional reconstructions based on electron microscopy. While there is considerable variety among synapses, small (around 1 μm diameter) synapses of the central nervous system typically have on the order of a hundred vesicles, of which only a small subset (approximately 5%) are in direct contact with the presynaptic membrane (49). This subset of vesicles, referred to as the docked pool, contacts the membrane in a region known as the active zone, in direct apposition across the synaptic cleft with a specialized area on the postsynaptic cell, known as the postsynaptic density (55).

When an AP arrives at a presynaptic terminal, the depolarization leads to Ca2+ channel opening. Calcium ions rush into the terminal down their electrochemical gradient and bind to a Ca2+ sensor (5), widely thought to be synaptotagmin on the synaptic vesicle membrane (10, 31, 44, 61). Through a series of steps that take less than a millisecond and are not fully understood, this binding leads to SNARE-dependent membrane fusion of the vesicle with the membrane and release of neurotransmitter into the synaptic cleft (11). Neurotransmitter quickly diffuses across the cleft and binds to postsynaptic ionotropic receptors that cause rapid conductance changes and/or metabotropic receptors that lead to slower effects mediated by G-protein coupled receptors in the postsynaptic cell.

A framework to study neurotransmitter release

A simple model used as a framework to study this process posits that as a result of a single AP in the presynaptic neuron, a response Q is elicited in the postsynaptic cell (54):

| (1) |

where

- n = the number of primed vesicles, i.e. vesicles immediately available for fusion (also known as the readily releasable pool or RRP). These vesicles have undergone all biochemical steps except for the final Ca2+-dependent fusion step.

- Pv = the probability that each of those vesicles has of fusing with the membrane in response to one AP

- q = the size of the postsynaptic response to a single vesicle fusion event (also known as quantal size)

Two important assumptions implicit in this model are that all primed vesicles have the same fusion probability and that they behave independently. Even if these assumptions do not hold in every case, the model is still a very useful way to think about synaptic transmission. Note that the model makes no restrictions on the possibility of more than one vesicle fusing at once (multivesicular release) at a given synapse. For some time there was a debate regarding whether multivesicular release could take place at synapses of the mammalian central nervous system. However, there is now convincing evidence that this can happen (2-4, 43) so it does not seem warranted to modify the model to restrict the possibility of multivesicular release occurring. Finally, a very important point regards how this model connects to the typically measured parameter Pr (neurotransmitter release probability). Pr is the probability that a synapse will not fail (14), that is, that a presynaptic AP will elicit a response in the postsynaptic cell. This will be equivalent to the probability that at least one vesicle fuses in response to one AP. Given the implicit binomial distribution underlying the model:

| (2) |

With this framework in mind, it is worth exploring how n, Pv, and q can be influenced to determine synaptic strength.

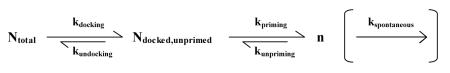

Several factors can influence the number of primed vesicles. In a simplified model, n will be set by the interplay of rates of docking (and undocking), priming (and unpriming) and possibly (see below) spontaneous fusion (Fig. 1A1):

|

where

- Ntotal = the total number of synaptic vesicles in a nerve terminal

- Ndocked,unprimed = the number of vesicles in contact with the presynaptic membrane that are not fusion competent

- ki= rate constants for process i, where i can be: docking, undocking, priming, unpriming and spontaneous vesicle fusion

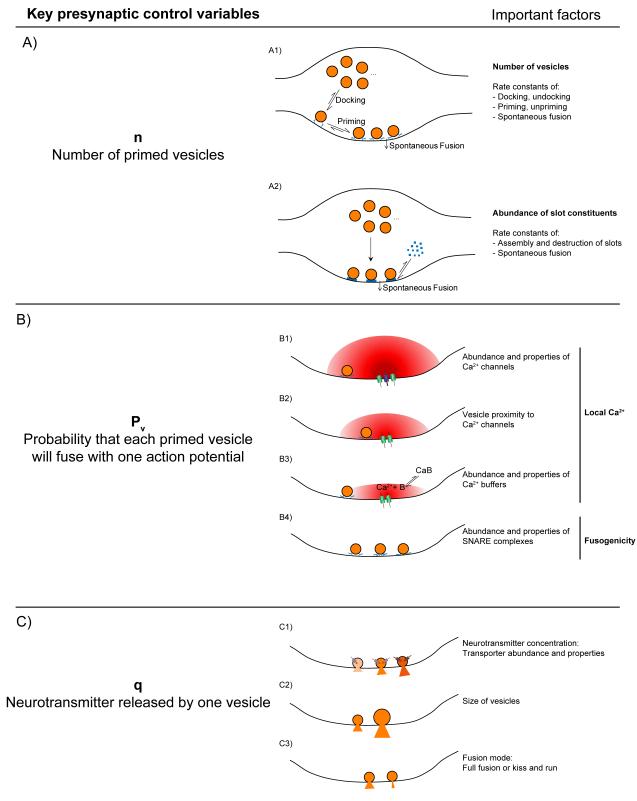

FIGURE 1.

Key presynaptic variables controlling the amount of neurotransmitter released in response to a single action potential. A) Models of priming with possible mechanisms to control the number of primed vesicles (n). A1) n is determined by the equilibrium between the rates of docking, undocking, priming, unpriming and spontaneous fusion. SNARE complexes are symbolized by crossed blue lines and are shown in a loose configuration in the case of the docked, unprimed vesicle. A2) Model that assumes the construction of release slots is the rate limiting factor for control of n, whereas other processes are at saturation. Molecules that make up the slots are shown as blue squares that assemble to form release sites at the membrane. B) Main determinants of vesicle fusion probability (Pv). B1) to B3) Factors that influence the local Ca2+ concentration at the vesicle. Ca2+ concentration is symbolized by the intensity of red. The higher the Ca2+ concentration at a vesicle, the higher its Pv. B4) Effects of abundance and properties of SNARE complexes. SNARE complexes are symbolized by crossed blue lines. Higher numbers of complexes per vesicle, or tighter complexes are presumed to lead to higher fusogenicity, and therefore higher Pv. C) Possible mechanisms controlling the amount of neurotransmitter released per vesicle (q). C1) The increasing intensity of orange symbolizes higher concentrations of neurotransmitter in each vesicle as a result of an increase in the number of transporters or their rates of transport. C2) Larger vesicles will release more molecules of neurotransmitter if the concentration is constant. C3) Small, flickering fusion pores might occur during kiss and run and lead to less neurotransmitter release per vesicle.

In this scenario, the rate constants of each step will influence n but so will any change in the total number of vesicles in the terminal, merely due to mass action. For example, anything that increased Ntotal would raise n without controlling docking or priming processes per se. Additionally, even in the absence of stimulation there is a low rate of neurotransmitter release due to spontaneous fusion of synaptic vesicles with the membrane. While there is some debate as to whether these vesicles are in the primed pool to begin with (19, 27, 28, 66), if they were, any change in the spontaneous fusion (or mini) rate could lead to a reduction in steady state n. An alternative proposal for the control of n posits that fusion can only take place at certain “slots” or “sites” (41). In this scenario control of the number of the sites is key. Thus, the important variables would be the abundance of molecules that make up the slots, and the rate constants of assembly and destruction of the sites (Fig. 1A2). These two scenarios are not incompatible, but rather should be considered extremes in a continuum of possibilities. The first implicitly assumes that the molecules necessary for fusion (presumably the site constituents) are in abundance and not rate limiting. Conversely, the second assumes that construction of sites is much slower than the docking and priming reactions such that once a site is formed, it captures a primed vesicle quickly. If the rates of the various processes outlined above are comparable, n will be set by a complex interplay between the number of vesicles, the number of sites and the rates of docking and priming within those sites. Which extreme of the model is a better representation of what actually occurs during priming is currently unknown. However, the fact that synaptic vesicle fusion and docking are localized to a specialized region of the plasma membrane (the active zone) supports the concept of slots, though what is rate-limiting in the process of docking and priming a vesicle at those sites is unclear.

An interesting question is whether docking is the morphological equivalent of priming or if any additional biochemical steps are needed to make a vesicle fusion competent. An illustrative example of how thinking on this point has evolved is munc13, the mammalian homolog of a Caenorhabditis elegans gene that causes severe paralysis when mutated (unc13), and contains domains that can bind phorbol esters and Ca2+ (9). Knocking out both isoforms expressed at hippocampal synapses eliminated neurotransmitter release (62). However, there was no effect on the number of docked vesicles determined from electron microscopy using an aldehyde fixation method. This was taken as evidence that after a synaptic vesicle docked, additional priming steps needed to take place before achieving fusion competence. This issue was revisited in a recent study on hippocampal slice cultures using high-pressure freezing and electron tomography, circumventing potential aldehyde fixation artifacts (58). Contrary to the previous findings, this study concluded that the docked vesicle pool was almost completely eliminated in the absence of munc13 and proposed that docking is the morphological correlate of priming in small synapses of the central nervous system. It is important to point out that exact definitions of what constituted a docked vesicle were slightly different in both studies (for further discussion of this issue, see 63), with the latter taking a stringent approach of only considering vesicles in contact with the plasma membrane and the former including vesicles within 6nm of the active zone. However, even applying the more inclusive criteria to the results using high-pressure freezing and electron tomography, the newer technique still shows a dramatic (~80%) reduction in the number of docked vesicles. Further study of additional mutants with high-pressure freezing and electron tomography will be needed to shed more light on whether docked vesicles are the morphological equivalent of the readily releasable pool. If there are additional biochemical steps necessary for fusion competence after vesicle docking, eliminating molecules critical only for those steps would lead to smaller n - assayed physiologically (see below) - yet no changes in the number of docked vesicles - assayed ultrastructurally -. On the contrary, if docking is equivalent to priming, we would expect a tight correlation of effects on n and the number of docked vesicles over a wide variety of molecular interventions. Based on results from docking of synaptic vesicles in C. elegans, or of dense core vesicles in chromaffin cells, particularly interesting candidates to revisit in mammalian synapses with high-pressure freezing are syntaxin, SNAP-25, synaptotagmin, and munc18 (12, 13, 22). Below, we discuss recent experiments reducing the levels of the protein RIM at the calyx Held (23), which causes a decrease in the primed pool size (assayed physiologically) that correlates well with a corresponding reduction in the number of docked vesicles (assayed by electron microscopy after chemical fixation). These recent experiments further support the idea that docking is the morphological equivalent of priming.

When considering how the value of Pv can be modulated, the main points to examine are local Ca2+ (its concentration at the vesicle) and vesicle fusogenicity (Fig. 1B). Pv is steeply dependent on the Ca2+ concentration at synaptotagmin molecules on primed synaptic vesicles (7, 10, 52, 61) so control of that local concentration will have a strong effect on synaptic strength (53). Local levels of Ca2+ will be influenced both by how much Ca2+ comes into the terminal in the first place and by how much the concentration decays between the source (Ca2+ channels on the presynaptic membrane) and primed vesicles. The amount of Ca2+ influx will be set by the intrinsic characteristics and abundance of Ca2+ channels (Fig. 1B1), the extra- to intracellular electrochemical Ca2+ gradient and the shape of the AP waveform. The concentration decay to the vesicle will depend on the average distance between vesicles and Ca2+ channels (referred to as the coupling between them, Fig. 1B2) and will also be shaped by any molecules between the channels and vesicles that can bind Ca2+ (Fig. 1B3). Depending on their concentrations, mobility, binding and unbinding rate constants, these Ca2+ buffers can potentially influence the local concentration of Ca2+ at primed vesicles (56). The second major determinant of Pv is primed vesicle fusogenicity (Fig. 1B4). This will be a combination of how intrinsically fusion willing a primed vesicle is - which can be estimated from spontaneous release rates under conditions of very low Ca2+ - and how the likelihood of fusing with the membrane increases as calcium ions bind to synaptotagmin molecules on the vesicle (34). Fusion willingness might depend on the exact state of the trans-SNARE complexes that are necessary for fusion. Another potential influence would be the abundance of SNARE complexes on a primed vesicle (39), which will be set by the combined local concentrations of the SNARE complex constituents: syntaxin, SNAP25 (on the presynaptic membrane) and synaptobrevin (on the synaptic vesicle). Thus, molecules such as complexin, tomosyn or munc18 that can interact with the assembled SNARE complex or its constituents could potentially alter the likelihood that a vesicle will fuse by affecting the abundance or conformation of trans-SNARE complexes (67). Additionally, the details of how Ca2+ sensors bind Ca2+ and how those changes increase the likelihood of vesicle fusion will be critical in setting vesicle fusogenicity (34, 61).

For q, there can be both pre- and postsynaptic influences. On the presynaptic side, the amount of neurotransmitter per vesicle might vary with the number or activity of neurotransmitter vesicular transporters present (Fig. 1C1) and the vesicle size (Fig. 1C2). Additionally, there is a controversy regarding “kiss and run”, i.e. events that do not lead to full fusion and collapse of the vesicle (16, 21, 24, 73). If these events involve a small pore that opens only briefly or flickers, they could lead to less neurotransmitter release into the cleft (Fig. 1C3). Finally, while we focus on presynaptic properties in this review, it is worth keeping in mind that the abundance and specific properties of postsynaptic receptors, together with their orientation relative to release sites, can profoundly influence the size of the postsynaptic response.

So far, we have discussed what happens when a single AP invades the nerve terminal. However, neurons can burst, firing many APs at frequencies up to 100 Hz and higher. Under those circumstances synaptic transmission will be influenced by factors beyond those considered above (18, 68). The size of the primed pool of vesicles at any given moment will be determined by the balance of vesicle fusion and priming rates. Under conditions of sustained activity, not only vesicle fusion, but also priming rates are Ca2+ dependent (17, 42, 59, 65). Therefore, Ca2+ channel inactivation (69) or facilitation (29, 38), exhaustion of extracellular Ca2+ in the synaptic cleft (8, 46), saturation of intracellular Ca2+ buffers (6) and the rates of Ca2+ clearance (57) during a burst of APs can all shape the postsynaptic response. Additionally, if there are slots for release, these might require a clearance time before they become available once more (26, 41). Finally, on the postsynaptic side receptors may saturate, desensitize (68) or even diffuse in and out of the postsynaptic density (25) during a burst. These effects can complicate attempts to use postsynaptic measurements as linear indicators of presynaptic activity.

Model systems and methods to study synaptic transmission

Given this panoply of potential influences on the neurotransmitter release process, to convincingly ascribe the functions of a molecule to any one of the processes mentioned above requires considerable effort. Typical experiments involve genetic manipulation of neurons to eliminate or replace certain molecules or increase their concentration. If there are pharmacological tools available to interfere with a molecule’s function these can also be used, ideally coupled with experiments in the absence of the molecule to test for any off-target effects. There are many possible techniques and preparations to estimate n, Pv and q, with a few general considerations applicable to any of them. Methods to measure n tend to rely on a strong, fast stimulus that causes exocytosis of all primed vesicles before there is time for significant replenishment of that pool of vesicles through priming processes. Under those conditions, the size of the response will be equivalent to n. In cases where there is significant replenishment during the stimulus, a model of the vesicle priming process is needed to correct the estimate appropriately. To measure Pv, the size of the response to one AP is simply divided by n. This places a minimum requirement on the sensitivity of any method used to determine Pv, as it must be possible to measure the response to a single AP precisely. Finally, to estimate q it is necessary to determine the postsynaptic response to a single vesicle fusion event or quanta. A usual approach is to use the average response to spontaneous, low frequency events that happen in the absence of stimulation and which are presumed to correspond to single vesicles fusing.

The best biophysical measurements of synaptic transmission currently available come from the calyx of Held, a large, cup-like excitatory synapse in the auditory pathway (47, 50). This giant synapse has hundreds of active zones and effectively operates as a parallel array of small synapses. It has become a valuable model system to study synaptic transmission because its large size makes it amenable to both pre and postsynaptic whole-cell recording and Ca2+ uncaging experiments. In this synapse n has been estimated as the size of the response to a step increase in Ca2+ concentration using uncaging, a constant current or a burst of APs. At the moment, Ca2+ uncaging is the only tool that allows unambiguous separation of effects on local Ca2+ and vesicle fusogenicity by bypassing Ca2+ channels entirely and elevating Ca2+ with spatial uniformity to cause neurotransmitter release. The resulting measure of the intracellular Ca2+ sensitivity of neurotransmitter release can be used - in combination with modeling - to test whether an intervention changes vesicles’ basal fusion willingness or, alternatively, modifies how their likelihood of fusing scales with increasing Ca2+ (34). Critically, factors that affect fusogenicity can be assayed independently of whether the intervention of interest led to a modification of local Ca2+ levels after an AP. Historically, the main disadvantage of the calyx of Held preparation has been the difficulty in achieving molecular control of the system beyond non-lethal knockouts or peptide injections (but see below).

Perhaps the most widely used system for molecular studies of presynaptic release in mammalian synapses is primary culture of cortical or hippocampal rodent neurons, studied electrophysiologically. Cultures of neurons can be prepared easily from genetically modified mice and studied even in cases where the mutations are lethal beyond birth. Simple transfection protocols to knock down, overexpress or replace proteins of interest can be used for detailed studies of structure-function relationships. In these cultures, which can be dissociated or autaptic (where a single neuron is grown on a microisland of glia and synapses onto itself), n is usually estimated as the response to application of a hypertonic solution containing 500 mOsm of sucrose. This stimulus was shown to correlate with the size of the primed pool of vesicles as determined by depletion experiments using bursts of action potentials (45). However, the mechanism involved remains mysterious and its correspondence with primed vesicles accessed with physiological stimuli is under debate (40, 60). Alternatively, bursts of 20-40 APs at 20-40 Hz have been used to deplete the pool. Unfortunately, there is typically substantial replenishment of primed vesicles during this stimulus and a large correction must be applied (40, 60). A downside of the primary culture system was, until very recently (10), the inability to perform Ca2+ uncaging experiments to directly probe the intracellular Ca2+ sensitivity of the fusion process. Additionally, any electrophysiological method will be affected by the complications inherent in using a postsynaptic measure to estimate presynaptic function.

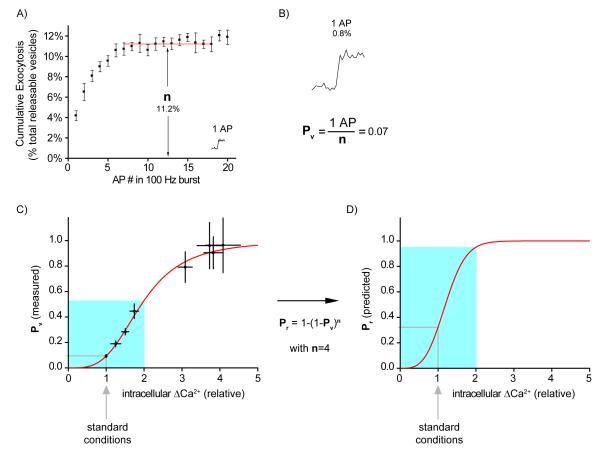

A recent method developed by our group (3) offers another potential way of studying Pv and n using a direct optical presynaptic readout based on the pH-sensitive GFP, pHluorin (36), tagged to the lumen of the vesicular glutamate transporter (64). Synaptic vesicles are acidic (pH of around 5.6) so upon fusing to the membrane and exchanging protons with the extracellular milieu there is an increase in pH to approximately 7.4. The pKa of the fluorescent reporter (around 7.1) is such that it increases its fluorescence around 20-fold upon that transition (48). Under appropriate imaging conditions, a response to a single AP can be detected with a temporal resolution of 10ms (3, see also, 4, 20). n can be determined by measuring the saturation of exocytosis in response to a burst of APs at 100 Hz (Fig. 2A). Conveniently, under these stimulation conditions exocytosis completely exhausts the RRP before it can be repopulated with new vesicles. Therefore, there is no need to correct the estimate of primed pool size due to refilling, as is typically the case when using weaker stimulation protocols (40, 60). Subsequently, by comparing the response to one AP with the RRP size, we obtain Pv (Fig. 2B). Importantly, the saturation of exocytosis with 100 Hz stimulation is not the result of Ca2+ channel inactivation and agrees well with an alternative method using single APs under conditions of very large Ca2+ entry (3). Using this sensitive technique we also studied how Pv varied as a function of increases in intracellular Ca2+ in response to a single AP (Fig. 2C). The resulting sigmoidal relationship where standard Ca2+ conditions are situated quite low on the curve highlights how small changes in Ca2+ entry can lead to large effects on baseline Pv. These changes in Pv will presumably cause even greater shifts in Pr (using our estimate of n=4 vesicles in equation (1), Fig. 2D) illustrating how forms of modulation that regulate Ca2+ entry even slightly can sharply modify synaptic efficacy. Regrettably, our method does not allow a study of q, and has less temporal resolution and sensitivity than electrophysiological methods. However, the lack of a postsynaptic component to the measurements can simplify the study of Pv and n. Furthermore, in contrast to electrophysiological studies in culture, it is not affected by changes in the number of synaptic contacts since measurements come from averages - not sums - across synapses. Finally, because it provides information from individual small synapses in parallel, it can potentially allow studies of determinants of synaptic strength between synapses of the same axon (unpublished work from our lab).

FIGURE 2.

Optical method used to determine n and Pv (3). A) Exocytosis is measured in response to a burst of 20 APs at 100 Hz in the presence of elevated (4mM) extracellular Ca2+ (average of 12 synapses across 4 trials). After six APs there is no further exocytosis indicating depletion of a readily releasable pool of vesicles. Thus, the amplitude of this plateau is a measure of n. Note that the exocytosis rate drops to zero and thus there is no need to apply a correction for refilling of the RRP during the stimulus. Inset: response to 1 AP in 2 mM external Ca2+; exocytosis on same scale. B) Response to a single AP under standard Ca2+ conditions (2 mM) can be measured with excellent sensitivity (top, average of 20 trials, scaled up four-fold from inset in A)). Dividing the response to one AP by n provides an estimate of Pv. C) The same techniques can be combined with Ca2+ imaging to estimate Pv as a function of intracellular Ca2+ increases in response to 1 AP. Note the sigmoidal curve resulting from the Hill relation with a cooperativity coefficient of 3.4, in excellent agreement with equivalent experiments performed previously in the calyx of Held (51). D) Using equation 1 and an estimate of the RRP size of 4 vesicles we can predict the relation of Pr to increases in intracellular Ca2+ based on the measured relationship between the latter and Pv. Light blue shading in C) and D) indicates region where Ca2+ entry can be modulated from 0 to 2-fold of normal, with corresponding effects on Pv and Pr. Note that the expected dependence of Pr on Ca2+ is steeper around the standard conditions region (2 mM extracellular Ca2+). Data in A), B) and C) comes from reference (3).

In what remains, we discuss a few recent exciting studies where molecules involved in neurotransmitter release were analyzed in sufficient detail to determine their function in terms of the models and concepts presented above. The examples come mainly from the calyx of Held, where new tools have been developed that allow molecular control at this synapse.

RIM, a multi functional coordinator of neurotransmitter release

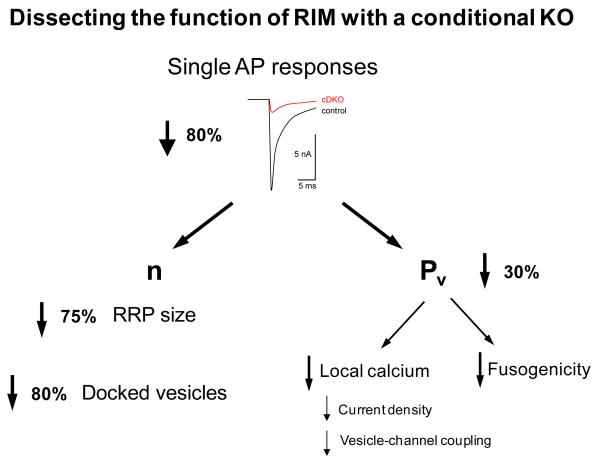

A recent set of papers (15, 23, 30) has probed with exquisite detail the functions of the RIMs, a set of proteins enriched at active zones, with multiple domains that allow them to interact directly with Ca2+ channels, synaptic vesicles, the active zone machinery and the priming protein munc13 (37). In a series of elegant experiments where the major isoforms of RIM were eliminated selectively at the calyx of Held by conditional knockout (23), a number of interesting results were obtained that can be placed in the framework presented previously (Fig. 3). An 80% reduction in the response to a single AP was used a starting point for a thorough dissection of the consequences of the absence of RIM. The reduction in synaptic strength was mostly attributed to an RRP size defect (75% reduction in n), and to a lesser extent to a reduction in Pv (30% decrease). n was determined from two independent methods (depletion using AP bursts or Ca2+ uncaging), giving very similar results. Furthermore, electron microscopy showed that a reduction in the number of docked vesicles (80%) could completely account for the drop in the number of primed vesicles, suggesting that at this synapse the former is the morphological equivalent of the latter. As regards the reduction in Pv, further experiments were carried out that showed a decrease in synaptic - but not somatic - Ca2+ current density, a looser coupling between those channels and synaptic vesicles and even a slightly lower intracellular Ca2+ sensitivity of vesicles. Other tests excluded the possibility of effects on Ca2+ channel inactivation, AP waveform or on postsynaptic receptors. An analogous study on hippocampal cultures came to similar conclusions and added interesting molecular details to the picture by localizing the effects on Pv to RIM’s PDZ domain and those on n to the N-terminus of the protein (30). Interestingly, the RIM PDZ domain was shown to interact directly with N and P/Q type Ca2+ channels. The same study also showed a reduction in the abundance of synaptic Ca2+ channels by immunostaining, consistent with the reduction in Ca2+ current density seen at the calyx. As regards the effect on n, another study showed that RIM inhibits the homodimerization of munc13 (15). Since homodimerized munc13 is unable to prime synaptic vesicles, this could explain why the absence of RIM leads to a priming defect.

FIGURE 3.

Dissecting the effects of a reduction in RIM at the calyx of Held (23). A conditional knockout of RIM at the calyx of Held led to an 80% decrease in responses to single APs (redrawn from ref. 23). This was dissected as the combination of a large effect on n (75%) and a smaller one on Pv (30%). The drop in RRP size (measured physiologically) was accompanied by a corresponding reduction in the docked vesicle pool (measured ultrastructurally), suggesting that the latter is the morphological equivalent of the former at this synapse. The drop in Pv was due to a reduction in local Ca2+ (caused by lower current density and looser coupling between channels and vesicles) and a decrease in fusogenicity of primed vesicles.

These recent studies on RIM highlight how one family of proteins, by virtue of interactions with many other players, can be involved in the regulation of several aspects of neurotransmitter release. Given its coordinated functions, relatively short half-life (around 1h, (71)) and correlation with activity at the single synapse level (33), it will be interesting to see if the level of RIM at a synapse operates as a dynamic, rate-limiting control variable that sets synaptic strength.

Synaptotagmin, not just a Ca2+ sensor for neurotransmitter release

Another recent paper illustrates how even a molecule such as synaptotagmin, which has a well-established role as the Ca2+ sensor for neurotransmitter release, can have other functions that become evident with newer techniques (72). A novel molecular approach for the calyx of Held preparation was developed by creating a recombinant adenovirus that can be injected perinatally to achieve overexpression of a protein of interest in this synapse. This system was used to study in more detail a previously characterized mutant of synaptotagmin that had normal Ca2+ binding and folding properties (70) yet could not rescue synaptic transmission when introduced into a null background, hinting at other functions of synaptotagmin beyond its role as the Ca2+ sensor. A ~75% reduction in the response to a single AP was due to a reduction in both n and Pv. The number of primed vesicles was reduced ~40%, whereas Pv suffered a ~45% reduction when the mutant variant of synaptotagmin was overexpressed. Furthermore, the effect on Pv was not due to a change in Ca2+ currents or fusogenicity of primed vesicles, leading to the conclusion that the coupling between channels and vesicles had been affected and depended on the mutated residues present in synaptotagmin. In addition to the effects on isolated action potentials, this conversion of the calyx of Held to a lower Pv state led to facilitation during bursts of APs, illustrating how changes in single AP release parameters can potentially influence circuit function through effects on short term plasticity. This study is another example of how adding molecular control to a preparation where rigorous biophysical methods are available can lead to new insights.

Conclusions

The picture that emerges from these recent studies is a complex one, with molecules exercising several functions through their various domains whose effects can only be discerned through careful experimentation. The development of new techniques that bring increasing molecular control to the calyx of Held are exciting breakthroughs. A combination of adenovirus expression strategy with conditional knockouts in the calyx of Held, will allow even more sophisticated structure-function experiments to take place at what remains the central nervous system synapse most amenable to detailed biophysical studies (for an early example of the potential for this kind of study, see (32)). On the other hand, in the autaptic neuronal culture system, the recent development of Ca2+ uncaging will expand the applicability of this powerful biophysical technique to a widely used preparation (10). Finally, our own methods promise to bring the study of Pv and n down to the level of individual small synapses (3), where it will be possible to explore the nature and basis synapse to synapse variation in Pv and n. The combination of these different experimental avenues of attack should lead to exciting discoveries that will expand our knowledge of the molecules that act as presynaptic determinants of neurotransmitter release.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funds from the NIH (NS036942, MH085783) to TAR and the David Rockefeller Graduate Program of the Rockefeller University (PA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott LF, Regehr WG. Synaptic computation. Nature. 2004;431:796–803. doi: 10.1038/nature03010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abenavoli A, Forti L, Bossi M, Bergamaschi A, Villa A, Malgaroli A. Multimodal quantal release at individual hippocampal synapses: evidence for no lateral inhibition. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6336–6346. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06336.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ariel P, Ryan TA. Optical mapping of release properties in synapses. Front Neural Circuits. 2010;4 doi: 10.3389/fncir.2010.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balaji J, Ryan TA. Single-vesicle imaging reveals that synaptic vesicle exocytosis and endocytosis are coupled by a single stochastic mode. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20576–20581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707574105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett MR. The concept of a calcium sensor in transmitter release. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;59:243–277. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blatow M, Caputi A, Burnashev N, Monyer H, Rozov A. Ca2+ buffer saturation underlies paired pulse facilitation in calbindin-D28k-containing terminals. Neuron. 2003;38:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bollmann JH, Sakmann B, Borst JG. Calcium sensitivity of glutamate release in a calyx-type terminal. Science. 2000;289:953–957. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borst JG, Sakmann B. Depletion of calcium in the synaptic cleft of a calyx-type synapse in the rat brainstem. J Physiol. 1999;521(Pt 1):123–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brose N, Hofmann K, Hata Y, Sudhof TC. Mammalian homologues of Caenorhabditis elegans unc-13 gene define novel family of C2-domain proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25273–25280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.25273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burgalossi A, Jung S, Meyer G, Jockusch WJ, Jahn O, Taschenberger H, O’Connor VM, Nishiki T, Takahashi M, Brose N, Rhee JS. SNARE protein recycling by alphaSNAP and betaSNAP supports synaptic vesicle priming. Neuron. 2010;68:473–487. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman ER. How does synaptotagmin trigger neurotransmitter release? Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:615–641. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.062005.101135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Wit H. Morphological docking of secretory vesicles. Histochem Cell Biol. 2010;134:103–113. doi: 10.1007/s00418-010-0719-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Wit H, Walter AM, Milosevic I, Gulyas-Kovacs A, Riedel D, Sorensen JB, Verhage M. Synaptotagmin-1 docks secretory vesicles to syntaxin-1/SNAP-25 acceptor complexes. Cell. 2009;138:935–946. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Castillo J, Katz B. Quantal components of the end-plate potential. J Physiol. 1954;124:560–573. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng L, Kaeser PS, Xu W, Sudhof TC. RIM proteins activate vesicle priming by reversing autoinhibitory homodimerization of Munc13. Neuron. 2011;69:317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dittman J, Ryan TA. Molecular circuitry of endocytosis at nerve terminals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:133–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dittman JS, Regehr WG. Calcium dependence and recovery kinetics of presynaptic depression at the climbing fiber to Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6147–6162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06147.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fioravante D, Regehr WG. Short-term forms of presynaptic plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21:269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fredj NB, Burrone J. A resting pool of vesicles is responsible for spontaneous vesicle fusion at the synapse. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:751–758. doi: 10.1038/nn.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Granseth B, Odermatt B, Royle SJ, Lagnado L. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is the dominant mechanism of vesicle retrieval at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2006;51:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Granseth B, Odermatt B, Royle SJ, Lagnado L. Comment on “The dynamic control of kiss-and-run and vesicular reuse probed with single nanoparticles”. Science. 2009;325:1499. doi: 10.1126/science.1175790. author reply 1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammarlund M, Palfreyman MT, Watanabe S, Olsen S, Jorgensen EM. Open syntaxin docks synaptic vesicles. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han Y, Kaeser PS, Sudhof TC, Schneggenburger R. RIM determines Ca(2)+ channel density and vesicle docking at the presynaptic active zone. Neuron. 2011;69:304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He L, Wu LG. The debate on the kiss-and-run fusion at synapses. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:447–455. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heine M, Groc L, Frischknecht R, Beique JC, Lounis B, Rumbaugh G, Huganir RL, Cognet L, Choquet D. Surface mobility of postsynaptic AMPARs tunes synaptic transmission. Science. 2008;320:201–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1152089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosoi N, Holt M, Sakaba T. Calcium dependence of exo- and endocytotic coupling at a glutamatergic synapse. Neuron. 2009;63:216–229. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hua Y, Sinha R, Martineau M, Kahms M, Klingauf J. A common origin of synaptic vesicles undergoing evoked and spontaneous fusion. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1451–1453. doi: 10.1038/nn.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hua Z, Leal-Ortiz S, Foss SM, Waites CL, Garner CC, Voglmaier SM, Edwards RH. v-SNARE Composition Distinguishes Synaptic Vesicle Pools. Neuron. 2011;71:474–487. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishikawa T, Kaneko M, Shin HS, Takahashi T. Presynaptic N-type and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels mediating synaptic transmission at the calyx of Held of mice. J Physiol. 2005;568:199–209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaeser PS, Deng L, Wang Y, Dulubova I, Liu X, Rizo J, Sudhof TC. RIM proteins tether Ca2+ channels to presynaptic active zones via a direct PDZ-domain interaction. Cell. 2011;144:282–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kochubey O, Lou X, Schneggenburger R. Regulation of transmitter release by Ca(2+) and synaptotagmin: insights from a large CNS synapse. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kochubey O, Schneggenburger R. Synaptotagmin increases the dynamic range of synapses by driving Ca(2)+-evoked release and by clamping a near-linear remaining Ca(2)+ sensor. Neuron. 2011;69:736–748. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lazarevic V, Schone C, Heine M, Gundelfinger ED, Fejtova A. Extensive Remodeling of the Presynaptic Cytomatrix upon Homeostatic Adaptation to Network Activity Silencing. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10189–10200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2088-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lou X, Scheuss V, Schneggenburger R. Allosteric modulation of the presynaptic Ca2+ sensor for vesicle fusion. Nature. 2005;435:497–501. doi: 10.1038/nature03568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McBain CJ, Kauer JA. Presynaptic plasticity: targeted control of inhibitory networks. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miesenbock G, De Angelis DA, Rothman JE. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature. 1998;394:192–195. doi: 10.1038/28190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mittelstaedt T, Alvarez-Baron E, Schoch S. RIM proteins and their role in synapse function. Biol Chem. 2010;391:599–606. doi: 10.1515/BC.2010.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mochida S, Few AP, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Regulation of presynaptic Ca(V)2.1 channels by Ca2+ sensor proteins mediates short-term synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;57:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohrmann R, de Wit H, Verhage M, Neher E, Sorensen JB. Fast vesicle fusion in living cells requires at least three SNARE complexes. Science. 2010;330:502–505. doi: 10.1126/science.1193134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moulder KL, Mennerick S. Reluctant vesicles contribute to the total readily releasable pool in glutamatergic hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3842–3850. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5231-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neher E. What is Rate-Limiting during Sustained Synaptic Activity: Vesicle Supply or the Availability of Release Sites. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2010;2:144. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2010.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neher E, Sakaba T. Multiple roles of calcium ions in the regulation of neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 2008;59:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oertner TG, Sabatini BL, Nimchinsky EA, Svoboda K. Facilitation at single synapses probed with optical quantal analysis. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:657–664. doi: 10.1038/nn867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pang ZP, Sudhof TC. Cell biology of Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenmund C, Stevens CF. Definition of the readily releasable pool of vesicles at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 1996;16:1197–1207. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rusakov DA, Fine A. Extracellular Ca2+ depletion contributes to fast activity-dependent modulation of synaptic transmission in the brain. Neuron. 2003;37:287–297. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakaba T, Schneggenburger R, Neher E. Estimation of quantal parameters at the calyx of Held synapse. Neurosci Res. 2002;44:343–356. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sankaranarayanan S, De Angelis D, Rothman JE, Ryan TA. The use of pHluorins for optical measurements of presynaptic activity. Biophys J. 2000;79:2199–2208. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76468-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schikorski T, Stevens CF. Quantitative Ultrastructural Analysis of Hippocampal Excitatory Synapses. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5858–5867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05858.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schneggenburger R, Forsythe ID. The calyx of Held. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:311–337. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schneggenburger R, Meyer AC, Neher E. Released Fraction and Total Size of a Pool of Immediately Available Transmitter Quanta at a Calyx Synapse. Neuron. 1999;23:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80789-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneggenburger R, Neher E. Intracellular calcium dependence of transmitter release rates at a fast central synapse. Nature. 2000;406:889–893. doi: 10.1038/35022702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schneggenburger R, Neher E. Presynaptic calcium and control of vesicle fusion. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schneggenburger R, Sakaba T, Neher E. Vesicle pools and short-term synaptic depression: lessons from a large synapse. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:206–212. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schoch S, Gundelfinger ED. Molecular organization of the presynaptic active zone. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:379–391. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0244-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwaller B. Cytosolic Ca2+ buffers. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a004051. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scullin CS, Wilson MC, Partridge LD. Developmental changes in presynaptic Ca(2 +) clearance kinetics and synaptic plasticity in mouse Schaffer collateral terminals. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:817–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siksou L, Varoqueaux F, Pascual O, Triller A, Brose N, Marty S. A common molecular basis for membrane docking and functional priming of synaptic vesicles. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stevens CF, Wesseling JF. Activity-dependent modulation of the rate at which synaptic vesicles become available to undergo exocytosis. Neuron. 1998;21:415–424. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80550-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stevens CF, Williams JH. Discharge of the readily releasable pool with action potentials at hippocampal synapses. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:3221–3229. doi: 10.1152/jn.00857.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun J, Pang ZP, Qin D, Fahim AT, Adachi R, Sudhof TC. A dual-Ca2+-sensor model for neurotransmitter release in a central synapse. Nature. 2007;450:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nature06308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Varoqueaux F, Sigler A, Rhee JS, Brose N, Enk C, Reim K, Rosenmund C. Total arrest of spontaneous and evoked synaptic transmission but normal synaptogenesis in the absence of Munc13-mediated vesicle priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9037–9042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122623799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Verhage M, Sorensen JB. Vesicle docking in regulated exocytosis. Traffic. 2008;9:1414–1424. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Voglmaier SM, Kam K, Yang H, Fortin DL, Hua Z, Nicoll RA, Edwards RH. Distinct endocytic pathways control the rate and extent of synaptic vesicle protein recycling. Neuron. 2006;51:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang LY, Kaczmarek LK. High-frequency firing helps replenish the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 1998;394:384–388. doi: 10.1038/28645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilhelm BG, Groemer TW, Rizzoli SO. The same synaptic vesicles drive active and spontaneous release. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1454–1456. doi: 10.1038/nn.2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wojcik SM, Brose N. Regulation of membrane fusion in synaptic excitation-secretion coupling: speed and accuracy matter. Neuron. 2007;55:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu-Friedman MA, Regehr WG. Structural contributions to short-term synaptic plasticity. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:69–85. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu J, Wu LG. The decrease in the presynaptic calcium current is a major cause of short-term depression at a calyx-type synapse. Neuron. 2005;46:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xue M, Ma C, Craig TK, Rosenmund C, Rizo J. The Janus-faced nature of the C(2)B domain is fundamental for synaptotagmin-1 function. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:1160–1168. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yao I, Takagi H, Ageta H, Kahyo T, Sato S, Hatanaka K, Fukuda Y, Chiba T, Morone N, Yuasa S, Inokuchi K, Ohtsuka T, Macgregor GR, Tanaka K, Setou M. SCRAPPER-dependent ubiquitination of active zone protein RIM1 regulates synaptic vesicle release. Cell. 2007;130:943–957. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Young SM, Jr., Neher E. Synaptotagmin has an essential function in synaptic vesicle positioning for synchronous release in addition to its role as a calcium sensor. Neuron. 2009;63:482–496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang Q, Li Y, Tsien RW. The dynamic control of kiss-and-run and vesicular reuse probed with single nanoparticles. Science. 2009;323:1448–1453. doi: 10.1126/science.1167373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]