to the editor: Provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) are expected to reduce the number of adults who delay seeking needed medical care because of cost.1 Reforms are expected to improve the ability to obtain care, in part, by extending Medicaid access to adults with incomes at or below 133% of the federal poverty line.2 A recent Supreme Court ruling gave greater latitude to state approaches to Medicaid expansion.3 Various state strategies for implementing reforms may amplify geographic variation in the prevalence of delayed care. Estimating the existing variation in and correlates of delayed care may assist states that are planning to improve access within and beyond the framework provided by the ACA.

We examined county-level geographic variation in the prevalence of care delayed because of cost among 289,333 adults who were 18 to 64 years of age in the 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey, a state-based telephone survey of health care access and health status. We calculated smoothed county-level prevalence estimates of delayed care using generalized linear mixed models.4 We examined the relationship between Medicaid eligibility thresholds for working adults with children and the odds that the BRFSS survey participants would delay seeking care. Statistical models were adjusted for the participants' sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and for the characteristics of the state and local health care infrastructure.5

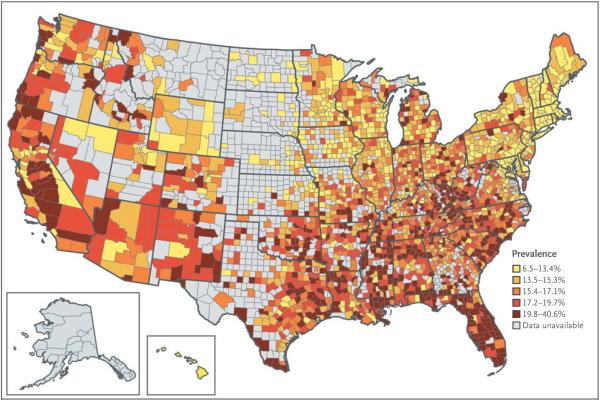

As shown in Figure 1, the county-level prevalence of delayed care ranged from 6.5% in Norfolk, Massachusetts, to 40.6% in Hidalgo, Texas. More restrictive Medicaid eligibility criteria were associated with a higher prevalence of delayed care than that observed when eligibility criteria were set at or above 133% of the federal poverty line. For example, the increased odds of delayed care was 16% as high among persons with incomes between 67 and 127% of the federal poverty line and 42% as high among persons with incomes between 17 and 44% of the federal poverty line. In addition, a higher concentration of primary care doctors was associated with a lower prevalence of delayed care (see Table 1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org). We reviewed data on the prevalence of delayed care in six counties in areas with different strategies for management of the health care infrastructure. Table 2 in the Supplementary Appendix shows that populations in counties with the highest prevalence of delayed care were more likely to be Hispanic and have low incomes and a high prevalence of chronic disease, and these areas had a relatively late history of state Medicaid expansion.

Figure 1. County-Level Smoothed Prevalence of Delayed Care Due to Cost among Adults between the Ages of 18 and 64 Years.

Data are from the 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey.

Our results suggest stark geographic differences in the prevalence of care delayed because of cost. Particularly vulnerable areas were in the South, including Texas and Florida. States and counties with a high prevalence of delayed care had a weaker health care infrastructure than states with a lower prevalence of delayed care. Since states determine strategies for implementing the ACA, areas with a high prevalence of delayed care should monitor their progress with the use of the BRFSS survey and other data sources. These states may require additional investments to “catch up” to places with a stronger infrastructure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG 032357) and from the National Institutes of Health (UL1 RR 025758-01) and by financial contributions from participating institutions of the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.The uninsured and the difference health insurance makes. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Un-insured; Washington, DC: 2012. http://www.kff.org/uninsured/upload/1420-14.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connors EE, Gostin LO. Health care reform — a historic moment in US social policy. JAMA. 2010;303:2521–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenbaum S, Westmoreland TM. The Supreme Court's surprising decision on the Medicaid expansion: how will the federal government and states proceed? Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1663–72. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bivand RS, Pebesma EJ, Gómez-Rubio V, editors. Applied spatial data analysis with R. Springer; New York: 2008. Modelling areal data; pp. 273–310. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carle AC. Fitting multilevel models in complex survey data with design weights: Recommendations. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.