Abstract

Environmental biofilms often contain mixed populations of different species. In these dense communities, competition between biofilm residents for limited nutrients such as iron, can be fierce, leading to the evolution of competitive factors that affect the ability of competitors to grow or form biofilms. We have discovered a compound(s) present in the conditioned culture fluids of Pseudomonas aeruginosa that disperses and inhibits the formation of biofilms produced by the facultative plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens. The inhibitory activity is strongly induced when P. aeruginosa is cultivated in iron-limited conditions, but it does not function through iron sequestration. In addition, the production of the inhibitory activity is not regulated by the global iron regulatory protein Fur, the iron-responsive extra-cytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factor PvdS, or three of the recognized P. aeruginosa quorum sensing systems. In addition, the compound(s) responsible for the inhibition and dispersal of A. tumefaciens biofilm formation is likely distinct from the recently identified P. aeruginosa dispersal factor, cis-2-decenoic acid (CDA), as dialysis of the culture fluids showed that the inhibitory compound was larger than CDA and culture fluids that dispersed and inhibited biofilm formation by A. tumefaciens had no effect on biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa.

Keywords: Biofilms, Inhibition, Dispersal, Iron

INTRODUCTION

There is a growing appreciation that bacteria in the environment exist primarily as multicellular communities known as biofilms. These bacterial aggregates assemble at interfaces and generally are encased in an extracellular polymeric matrix (Sutherland 2001; Whitchurch et al. 2002). In contrast to planktonically growing bacteria, the cells in a biofilm are typically more recalcitrant to antimicrobial treatment and predatory grazing, capable of maintaining extremely high local cell densities, and thus able to potentially facilitate the expression of quorum sensing controlled functions and horizontal gene transfer (Maeda et al. 2006; Horswill et al. 2007). These characteristics are of particular concern in many medically relevant contexts where biofilms often play a role in implant-associated infections, water-borne diseases, and the establishment of chronic infections (Costerton et al. 1999; Rather 2005; Lim et al. 2006). Biofilms are also problematic in a wide range of industrial and agricultural contexts where they are responsible for biofouling and spoilage (Danhorn et al. 2004; Coetser and Cloete 2005; Verran et al. 2008). Compounds that are capable of dispersing bacterial biofilms are therefore of clear practical application. One potential approach for the discovery and mechanistic elucidation of biofilm inhibitory compounds is to examine the competitive interactions that occur in single and multispecies biofilms. The high population density present in most biofilm communities represents a double-edged sword as bacteria in close proximity may benefit by cooperating but also compete for the limited resources available (Platt and Bever 2009; Hibbing et al. 2010). Because of this, biofilms are likely to foster intense intra- and interspecies competition among the diverse strains and species present.

Iron is a necessary nutrient for most bacteria and is one of the major limiting resources for which microorganisms compete. This element is extremely abundant but biologically unavailable in oxygen rich conditions at neutral pH, and is even more limited in the context of pathogenesis, where host organisms often sequester iron to limit the growth of pathogens (Chipperfield and Ratledge 2000; Weinberg 2009). Bacteria have evolved a range of competitive behaviors that facilitate the acquisition of iron from the environment and competing organisms. Many bacteria produce small molecules called siderophores to scavenge iron from the environment (Krewulak and Vogel 2008). In addition to their own siderophores, bacteria are often able to use those produced by other organisms as iron sources (Andrews et al. 2003; Rodionov et al. 2006). These molecules can mediate intra- and interspecies competition depending on differing iron affinities and the ability of competing organisms to use the siderophores produced by one another (Carson et al. 2000; Joshi et al. 2006; Buckling et al. 2007). In addition to the indirect competition for iron involving siderophores, Pseudomonas aeruginosa has been shown to kill Staphylococcus aureus and use the released iron (Mashburn et al. 2005). In addition to nutritional resources, bacteria also compete with one another for favorable locations in the environment. There are several facets to this form of competition, with bacteria producing adhesins to increase their chances of attachment, surface components to block invading bacteria, and secreted compounds to kill or disperse the previous biofilm inhabitants (Horie et al. 2002; Rao et al. 2006; Kolodkin-Gal et al. 2010; Martínez-Gil et al. 2010).

The opportunistic pathogen P. aeruginosa is a ubiquitous soil and water dwelling organism that has been intensively studied in the context of its virulence and serves as a model organism for quorum sensing and biofilm formation. P. aeruginosa has also been used to study multi-species competitive behaviors and is capable of producing a wide range of secreted compounds that can potentially serve to mediate competitive interactions (An et al. submitted). These compounds can function in a variety of ways to kill or inhibit the growth of competing organisms [An et al. submitted and (Schuster et al. 2003)]. At least two different compounds secreted by P. aeruginosa have been shown to influence biofilm formation in a competitive context. The amphipathic rhamnolipids are responsible for modulating the structure and dispersal of P. aeruginosa biofilm as well as for dispersing biofilms formed by Bordetella bronchiseptica (Boles et al. 2005; Irie et al. 2005; Glick et al. 2010). The short chain fatty acid cis-2-decenoic acid (CDA), also produced by P. aeruginosa, has been shown to disperse biofilms formed by a variety of prokaryotes and the fungus Candida albicans (Davies and Marques 2009).

The α-proteobacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens is a ubiquitous soil microorganism that is best known as the causative agent of crown-gall neoplasia on dicotyledonous plants via cross-kingdom horizontal gene transfer (Escobar and Dandekar 2003). A. tumefaciens can be isolated from many of the same environments from which P. aeruginosa can be isolated, and these bacteria have been used previously as a model for the examination of dual-species interactions in biofilms (An et al. 2006). In these assays, P. aeruginosa was shown to dominate the biofilms formed in both static and flowing conditions via a higher growth-rate and to further outcompete A. tumefaciens during stationary phase in a quorum sensing dependent fashion (An et al. 2006).

In this study, we examined the effects of compounds present in the conditioned culture fluids of P. aeruginosa on the biofilm formation of A. tumefaciens. In the work by An et al., it was shown that an non-motile, aflagellate mutant of A. tumefaciens was able to produce slightly more adherent biomass in a continuous flow biofilm co-culture context (An et al. 2006). This observation led us to hypothesize that P. aeruginosa was producing a compound that stimulated A. tumefaciens to disperse from biofilms, and that the aflagellate mutant was unable to emigrate as efficiently, resulting in the increased biomass. We have found that P. aeruginosa produces a compound(s) that is capable of dispersing and inhibiting the formation of A. tumefaciens biofilms and that this activity is dramatically increased when P. aeruginosa is grown in iron limited conditions. We also show that the inhibition of A. tumefaciens biofilm formation is not due to iron sequestration, nor is it regulated by the P. aeruginosa quorum sensing systems or any of the other recognized mechanisms by which P. aeruginosa directly competes with other microbes.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions and reagents

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The P. aeruginosa strains were acquired from the strain collections of Matthew R. Parsek and E. Peter Greenberg. All media components and general reagents were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Both A. tumefaciens and P. aeruginosa strains were grown in Agrobacterium tumefaciens minimal medium with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose and 15 mM ammonium sulfate as a nitrogen source (ATGN) (Tempe et al. 1977). The FeSO4 called for in the original recipe was omitted for routine cultivation of bacteria with no effects on A. tumefaciens growth (Merritt et al. 2007). Synthetic cis-2-decenoic acid (CDA) was purchased from Carbosynth Limited, Berkshire, United Kingdom.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains

| Strain Name | Genotype | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. tumefaciens | C58 | Wild type | (Watson et al. 1975) |

| P. aeruginosa | PAO1 | Wild type | (Pesci et al. 1997) |

| P. aeruginosa | PTL5032 + pMRP9- 1 | pchA- + gfp (Carb) | U. of Washington (Jacobs et al. 2003) and (Kaneko et al. 2007) |

| P. aeruginosa | ΔpvdA + pMRP9-1 | ΔpvdA + gfp (Carb) | (Banin et al. 2005; Kaneko et al. 2007) |

| P. aeruginosa | ΔpchEF ΔpvdD + pMRO9-1 | ΔpchEF Δ pvdD + gfp (Carb) | Urs Ochsner, Replidyne Inc., Louisville, CO and (Kaneko et al. 2007) |

| P. aeruginosa | furC6Tc | furC6Tc | (Barton et al. 1996; Ochsner et al. 1999) |

| P. aeruginosa | ΔpvdS | ΔpvdS | (Ochsner and Vasil 1996) |

| P. aeruginosa | ΔhcnB | hcnB::ISlacZ/hah Tet | Dingding An, Unpublished |

| P. aeruginosa | PTL47305 | phzA1::ISphoA/hah Tet | U. of Washington (Jacobs et al. 2003) |

| P. aeruginosa | ΔrhlAB | ΔrhlAB Gm | (Shrout et al. 2006) |

| P. aeruginosa | AHP4C-GFP | hcnC::ISlacZ/hah phzA1::ISphoA/hah rhlB::hah miniTn7-gfp2- ωGm | Colin Manoil (Jacobs et al. 2003) |

| P. aeruginosa | PAO-JP1 | ΔlasI | (Pesci et al. 1997) |

| P. aeruginosa | PDO100 | ΔrhlI | (Pesci et al. 1997) |

| P. aeruginosa | PAO-JP2 | ΔlasI ΔrhlI | (Pesci et al. 1997) |

| P. aeruginosa | ΔlasRΔ rhlR-GFP | ΔlasRΔ rhlR mini Tn7-gfp3-SmΩKm | Michael Givskov |

| P. aeruginosa | PTL17628 | pqsA::Tet | U. of Washington (Jacobs et al. 2003) |

Preparation of A. tumefaciens and P. aeruginosa cell free culture fluids

Cultures of P. aeruginosa wild type and mutant strains and wild type A. tumefaciens were grown in ATGN with or without 22 μM FeSO4 at 28 °C with shaking to late stationary phase (for 72–96 hours). Bacterial cells were removed from cultures ranging from 5 ml to 500 ml by two centrifugations at 12,000 x g for 10 min followed by filtration through a 0.22 μm filter (Pall Life Sciences, Port Washington, NY). Filtered culture fluid was stored at 4 °C until ready for use.

Growth and analysis of static biofilm formation assays

P. aeruginosa static culture biofilm and pellicle assays were performed as described previously (O’Toole and Kolter 1998; Friedman and Kolter 2004). Overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa were grown in ATGN with no added FeSO4. These cultures were sub-cultured, to a final OD600 of 0.05, into ATGN with or without 22 μM FeSO4 and with or without 50% (vol/vol) P. aeruginosa culture fluids resulting in four different static biofilm assay inocula. These inocula were added to 12-well polystyrene tissue culture plate wells with polyvinyl chloride (PVC) cover-slips placed upright in the wells for surface biofilm and pellicle formation. These cultures were incubated for 24–72 hours at room temperature. The surface adhered biofilm was visualized by crystal violet (CV) staining and the pellicle biofilms were photographed.

A. tumefaciens static culture microtiter plate biofilm assays were performed as previously described (Ramey et al. 2004). For the biofilm assays to which culture fluids were added, overnight cultures of A. tumefaciens were grown in ATGN without FeSO4. Cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in ATGN containing 22 μM FeSO4 and varying concentrations of culture fluids. Concentrated ATGN was diluted with the appropriate amounts of culture fluids and water to ensure that there was always at least a 1X concentration of nutrients in the initial biofilm inoculum. For the high iron biofilms, the final concentration of FeSO4 was varied from 0–1100 μM in AGTN amended with 20% (vol/vol) culture fluids, synthetic cDA preparations or unsupplemented. The inoculated cultures were incubated in PVC 96-well microtiter plates at room temperature for 48 h. The amount of planktonic growth in the wells was estimated by OD600. The adherent biomass was stained for 10 min by the addition of 0.1% (wt/vol) CV for a final CV concentration of 0.014% (wt/vol). The stained biofilms were rinsed with distilled water and the stain was solubilized by the addition of 33% (vol/vol) acetic acid and quantified by reading the A600. Spectrophotometric measurements of the biofilms were taken using a Bio-Tek Synergy HT microplate reader (Winooski, VT). Data are reported as the means and standard deviations of at least three technical replicates.

Physical and enzymatic treatment of the P. aeruginosa culture fluids

Aliquots of culture fluids were boiled or exposed to ultra violet radiation at 254 nm in a Germfree laminar airflow workstation (Ormond Beach, FL) for 60 min. Enzymatic treatment of culture fluids was performed as described previously (Berne et al. 2010). Aliquots of culture fluids were incubated with 5 μg/ml of DNase, RNase, or Pronase beads overnight at room temperature. The RNase and DNase were inactivated by heating to 75 °C for 20 min. Pronase beads were removed by centrifugation at 18,000 x g for 1 min. The treated culture fluids were used in A. tumefaciens static culture biofilm assays as previously described to determine the impact of each treatment.

Dialysis of culture fluids and synthetic CDA

Aliquots of culture fluids (3 ml) and a suspension of synthetic CDA (52 mM) were placed in dialysis membrane cassettes (2000 Da and 7000 Da molecular weight cut off, MWCO; Slide-a-Lyzer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cassettes were then suspended in four liters of AT-N dialysis buffer (ATGN with the glucose omitted) overnight at room temperature with gentle agitation resulting in a 1333 fold dilution of the dialyzable molecules present in the culture fluids. The dialyzed suspensions were removed from dialysis cassettes and used in A. tumefaciens static culture biofilm assays to determine the remaining activity, compared to the same dilutions of undialyzed material incubated in parallel during dialysis.

Static biofilm dispersal assay

Static culture biofilms of A. tumefaciens were prepared as described above but incubated for only 24 h at room temperature. At 24 h post inoculation, culture fluids were added to a final concentration of 50% (vol/vol). An equal volume of ATGN was added to control wells. The OD600 of the bacteria in the planktonic phase was measured and adherent biomass was stained by the addition of CV at 0, 5, 10, 15, and 60 min post addition. The CV was removed and the stained wells were rinsed two times with distilled water 10 min after the addition of CV. Immediately after rinsing, 33% (vol/vol) acetic acid was added and the wells were incubated for 10 min to solubilize the CV stained adherent biomass. The amount of solubilized CV was quantified by reading the A600 as described above.

RESULTS

Pseudomonas produces a secreted inhibitor of Agrobacterium tumefaciens biofilm formation

A study from An et al. suggested that P. aeruginosa might produce a soluble inhibitor of A. tumefaciens biofilm formation (An et al. 2006). To test this, filtered cell-free culture fluids were prepared from stationary phase P. aeruginosa cultures (growth yields of OD600 between 1.0 and 2.0). This culture fluid was then used as a supplement in A. tumefaciens biofilm formation assays. The presence of P. aeruginosa culture fluids resulted in a dramatic decrease in the crystal violet stained adherent biomass observed in these biofilm assays (Figure 1A). This decrease was observable with the addition of 1% (vol/vol) culture fluids and reached a maximum between 10 and 30% (vol/vol). At higher concentrations the addition of these culture fluids also inhibited the planktonic growth of A. tumefaciens (Figure 1B). The addition of culture fluids prepared identically from A. tumefaciens cultures had no effect on biofilm formation (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1. The inhibitory activity of conditioned P. aeruginosa culture media on A. tumefaciens biofilm formation.

Quantification of A) acetic acid solubilized CV biofilm stain, measured as A600 and B) the planktonic growth, measured by OD600, prior to staining, from 48 h PVC 96-well microtiter plate A. tumefaciens C58 biofilms. Increasing concentrations of culture fluids that were prepared from A. tumefaciens low iron cultures (open triangle), and P. aeruginosa cultures from, iron replete (closed circle) and iron limited (open circle) conditions were added to the biofilm assays. Data are normalized relative to unsupplemented cultures. Quantification of C) the acetic acid solubilized CV, measured by A600 and D) the planktonic growth, measured by OD600 prior to staining, from 48 h PVC 96-well microtiter plate A. tumefaciens biofilms with increasing concentrations of FeSO4, with (open circles) or without (closed circles) 20% (vol/vol) P. aeruginosa culture fluids prepared from iron-limited cultures. Data are normalized relative to the cultures with 22 μM FeSO4 but with no added fluids. In all cases, values are the means and standard deviations from five wells per condition.

The biofilm effect of the P. aeruginosa culture fluids was not due to nutrient depletion as the amendments were prepared in concentrated media and diluted with the addition of either culture fluids or water to provide a 1X concentration of ATGN in addition to the nutrients remaining in the P. aeruginosa conditioned cell-free culture fluids. In addition, the inhibition was not the result of pH changes as the non-inhibitory A. tumefaciens fluids and the inhibitory P. aeruginosa culture fluids were both pH 6.5 compared to 6.7 for un-inoculated ATGN.

Inhibitor production is regulated by iron availability, but does not act through iron sequestration

P. aeruginosa is an aggressive competitor for iron and iron levels have a significant impact on its multicellular behaviors (Banin et al. 2005; Mashburn et al. 2005). Iron levels also have a profound effect on A. tumefaciens biofilm formation (Hibbing and et al., manuscript in preparation). We therefore utilized a range of iron concentrations during growth of P. aeruginosa and tested the effect of this variable on production of the A. tumefaciens biofilm inhibitory activity. We observed that supplementing ATGN medium with FeSO4 dramatically decreased production of the biofilm inhibitory activity (Figure 1A). The color of the culture fluids also changed from yellow in the unsupplemented culture to clear in the iron-replete culture, suggesting decreased production of the siderophore pyoverdine. In addition, after 72–96 h the growth yield of the P. aeruginosa culture with iron supplemented media increased to an OD600 of 2.0–5.0 (data not shown), approximately double that observed from the cultures grown in unsupplemented media.

The dramatic effect of iron levels on production of the biofilm inhibitory activity from P. aeruginosa cultures suggested that it might be due to one or more of the siderophores produced by P. aeruginosa, effectively limiting iron in the A. tumefaciens cultures and thereby inhibiting biofilm formation (Hibbing and Fuqua, manuscript in preparation). We tested the first of these hypotheses using culture fluids prepared from cultures of P. aeruginosa mutants that were unable to produce pyoverdine, pyochelin (the other major siderophore produced by strain PAO1), or both of the siderophores. None of these mutants were significantly abrogated for inhibitor production (Supplemental Table 1). To test whether iron sequestration by an alternate mechanism was causing the biofilm inhibition, we added additional FeSO4 to A. tumefaciens biofilm assays with or without supplemented culture fluids prepared from iron-limited wild type P. aeruginosa cultures. Iron concentrations from 22 μM to 220 μM FeSO4 did not diminish the effect on the biofilm inhibitory activity of the culture fluid. Iron concentrations greater than 220 μM inhibited biofilm formation and planktonic growth regardless of the presence of the P. aeruginosa culture fluids (Figure 1C and D).

Mutations in the global P. aeruginosa iron regulators fur and pvdS do not abolish iron-responsive control of its biofilm inhibitory activity

A common global iron-responsive regulator for many bacteria including P. aeruginosa is Fur, the ferric uptake repressor (Vasil and Ochsner 1999). The P. aeruginosa fur homolog is believed to be essential but missense mutations in this gene have been isolated that exhibit constitutive pyoverdine production and partially desensitize P. aeruginosa biofilm formation to iron limitation (Barton et al. 1996; Banin et al. 2005). In contrast, the deletion of the extra cytoplasmic function (ECF) σ-factor pvdS, involved in the response to iron limitation, resulted in the loss of pyoverdine production and formation of structurally aberrant biofilms in flow cells under iron replete conditions (Banin et al. 2005).

We hypothesized that one or both of these mutations would disrupt iron-responsive control of biofilm inhibitor production. Culture fluids were prepared from P. aeruginosa furC6Tc (a missense mutation that decreases fur activity) and ΔpvdS strains grown in minimal medium with and without 22 μM FeSO4. The pattern of biofilm inhibitory activity for both mutants remained iron-responsive, as culture fluids from the furC6Tc strain or the ΔpvdS mutants exhibited high inhibitory activity when prepared from iron limited-cultures and decreased inhibitory activity when prepared from iron replete cultures (Figure 2A). Planktonic growth of A. tumefaciens was, however, more acutely inhibited by the culture fluids from the furC6Tc and ΔpvdS mutants than by wild type P. aeruginosa culture fluids (Figure 2B), suggesting that these regulators potentially influence additional competitive factors.

Figure 2. Mutants in the global iron regulators Fur and PvdS retain iron dependent inhibition of A. tumefaciens biofilms.

Quantification of A) acetic acid solubilized CV biofilm stain, measured as A600 B) the planktonic growth, measured by OD600 prior to staining, from 48 h PVC 96-well plate A. tumefaciens biofilms. Increasing concentrations of culture fluids prepared from cultures of wild type P. aeruginosa (circles), the global iron-responsive regulatory gene missense mutant furC6Tc (squares) and the iron responsive ECF σ-factor mutant ΔpvdS (triangles) grown with (closed symbols) and without (open symbols) 22 μM FeSO4 were added to the biofilm assays. Values are normalized relative to cultures with no added fluids and are the means and standard deviations from five wells per condition.

Pre-formed A. tumefaciens biofilms are rapidly dispersed by P. aeruginosa culture fluids

The inhibition of A. tumefaciens biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa culture fluids could be due to a block in surface adhesion, the inhibition of biofilm maturation, or the inhibition could be caused by accelerated biofilm dispersal. To examine the latter possibility, we measured the effect of P. aeruginosa culture fluids on pre-formed A. tumefaciens biofilms. The addition of P. aeruginosa culture fluids to 24 h A. tumefaciens microtiter biofilm plate wells resulted in a rapid and dramatic decrease in the adherent biomass (Figure 3A). However, the addition of P. aeruginosa culture fluids had no effect on the planktonic culture growth of A. tumefaciens, identical to addition of the ATGN growth medium alone (Figure 3B). A modest level of dispersal was observed with addition of the ATGN medium alone. These experiments suggest that the P. aeruginosa culture fluids are capable of stimulating the dispersal of A. tumefaciens biofilms.

Figure 3. The addition of P. aeruginosa culture fluids causes the dispersal of preformed A. tumefaciens biofilms.

Static culture 24 h biofilms of A. tumefaciens. At time 0, ATGN (closed circles) or P. aeruginosa culture fluids (open circles) were added to the cultures resulting in treatment of the preformed biofilms with 50% (vol/vol) culture fluids or ATGN. At each time point A) the wells were stained with CV, incubated 10 min, the stain was solubilized with acetic acid, and measured at A600 and B) the planktonic growth of the culture, OD600 prior to staining. Values are normalized relative to the value at time 0, are the means and standard deviations from four wells per time-point.

Low iron conditions increase surface adherent biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa while decreasing planktonic growth and pellicle formation

There are two major biofilm conformations adopted by P. aeruginosa in static liquid culture, solid-surface associated biofilms and air-liquid interface-associated pellicles (Friedman and Kolter 2004). In the conditions used in this study, P. aeruginosa grown in static cultures for 24 hours with 22 μM FeSO4 produced thick pellicles with limited surface-attached biofilm and robust planktonic growth. In contrast those grown in static culture with no exogenous iron demonstrated less pellicle formation and planktonic growth, while forming dense surface-associated biofilms (Figure 4). After 48 hours, pellicle formation in the 22 μM FeSO4 conditions had dissipated and the small amount of surface adherent biomass had further decreased. The elevated amount of surface-adhered biomass in the iron-limited conditions was still present at 72 h but the pellicle was completely absent (Figure 4).

Figure 4. P. aeruginosa biofilm formation is not influenced by its own culture fluids but is impacted by iron levels.

P. aeruginosa

static culture biofilms were grown in 12-well microtiter dishes with PCV coverslips sitting vertically in the wells. After incubating for 16 h, 40 h, and 64 h the coverslips were removed and the adherent biomass was stained with CV, and the OD600 of the remaining planktonic culture was measured. The bacteria at the air-liquid interface were disrupted and photographed. The border between the pellicle suspended at the air-liquid interface (the lighter colored regions) and the planktonic bacteria (the darker colored regions) are marked with a white arrow. The images shown are representative of three coverslips. The OD600 values presented are the mean and (standard deviation) from three wells.

P. aeruginosa static biofilm formation does not respond to the culture fluids which inhibit A. tumefaciens

In order to test the effect of the inhibitory culture fluids on P. aeruginosa biofilm formation, static culture coverslip biofilms were cultivated in the presence or absence of 50% (vol/vol) culture fluids with or without added 22 μM FeSO4. P. aeruginosa exhibited increased biofilm formation and decreased planktonic growth under iron limitation, but the culture fluids had no apparent impact (Figure 4). The addition of 50% (vol/vol) of these same culture fluids completely abolishes A. tumefaciens biofilm formation with or without additional FeSO4 (Figure 1A and data not shown).

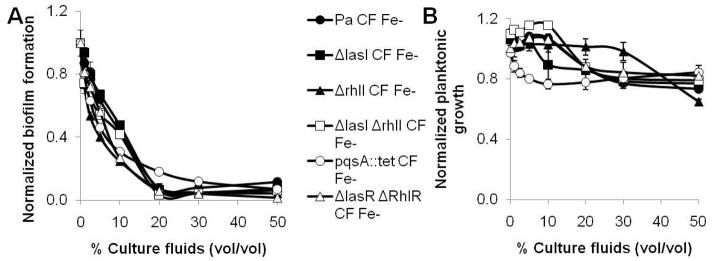

Inhibitor production is not regulated by the P. aeruginosa quorum sensing systems

The P. aeruginosa quorum sensing systems play a critical role in the regulation of its secreted virulence factors, antimicrobial agents, and anti-biofilm compounds. We therefore evaluated the possibility that the inhibitor might be regulated by quorum sensing as well. To test this hypothesis, culture fluids were prepared from five P. aeruginosa quorum sensing mutant strains, ΔlasI, ΔrhlI, ΔlasI ΔrhlI, ΔlasR ΔrhlR, and pqsA::tet. None of these mutants were found to be deficient for inhibition of A. tumefaciens biofilm formation or growth (Figure 5A and B).

Figure 5. Quorum sensing deficient mutants direct wild type levels of biofilm inhibition.

A) acetic acid solubilized CV biofilm stain, measured as A600 and B) the planktonic growth, measured by OD600 prior to staining, from 48 h PVC 96-well plate A. tumefaciens biofilms. Increasing concentrations of culture fluids prepared from wild type (closed circles) and the five quorum sensing deficient mutants used in this study, ΔlasI (closed squares), Δ rhlI (closed triangles), pqsA::tet (open circles), Δ lasI Δ rhlI (open squares), and Δ lasR Δ rhlR (open triangles), prepared from iron limited cultures were added to the biofilm assays. Values are normalized relative to cultures with no added fluids and are the means and standard deviations of five wells per condition.

Several recognized bioactive secreted compounds from P. aeruginosa are not responsible for biofilm inhibition

P. aeruginosa produces an array of secreted compounds with antimicrobial or anti-biofilm activity, including hydrogen cyanide, pyocyanin, and rhamnolipids. It seemed plausible that these compounds might be acting alone or in combination to inhibit biofilm formation by A. tumefaciens. To test this hypothesis, we prepared culture fluids from P. aeruginosa individual mutants that were unable to produce each of these compounds alone, as well as a triple mutant that could not produce any of these compounds. We found that inhibitor production was identical to wild type in all of the mutants tested (Supplemental Table 1).

The P. aeruginosa inhibitory activity is physically and enzymatically stable

The biofilm inhibitory activity was found to be fully resistant to boiling and exposure to UV radiation for one hour. The inhibitory activity was also completely stable over nearly a year stored at 4°C (Supplemental Table 2, data not shown). Exposure of the P. aeruginosa culture fluids to DNase, RNase, and Pronase enzymes for over 15 hours at room temperature did not significantly diminish the biofilm inhibitory activity, although these enzymes maintained their activity over this incubation period (Supplemental Table 2).

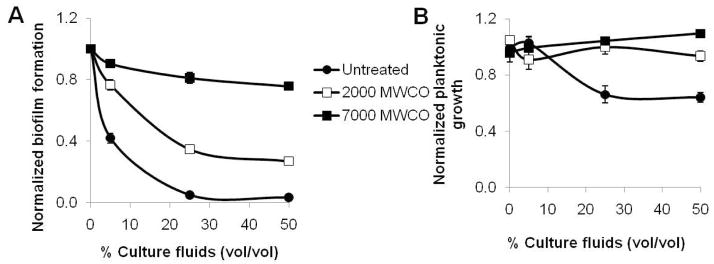

The inhibitory activity is predominantly due to a low molecular weight compound(s) that is distinct from CDA

To preliminarily establish a molecular size range for the inhibitory compound(s), the culture fluids were dialyzed using 2000 and 7000 Da pore size dialysis membranes. The majority of the biofilm inhibitory activity of the culture fluids was lost when dialyzed across a 7000 Da membrane, though a significant fraction of the inhibitory activity was retained when the fluids were dialyzed across a dialysis membrane with a 2000 Da cutoff (Figure 6A). In contrast, the ability of the culture fluids at high concentrations to inhibit the planktonic growth of A. tumefaciens was completely abrogated by dialysis across both the 7000 and the 2000 molecular size cutoff membranes (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Dialysis of P. aeruginosa culture fluids reveals a low molecular size for the active compound(s.

A) acetic acid solubilized CV biofilm stain, measured as A600 and B) the planktonic growth, measured by OD600 prior to staining, from 48 h PVC 96-well plate A. tumefaciens biofilms. Increasing concentrations of culture fluid that was either untreated (closed circles) or dialyzed across 2000 Da (open squares) or 7000 Da (closed squares) dialysis membranes into 4 liters of AT-N buffer were added to the biofilm assays. Values are normalized relative to cultures with no added fluids and are the means and standard deviations from five wells per condition.

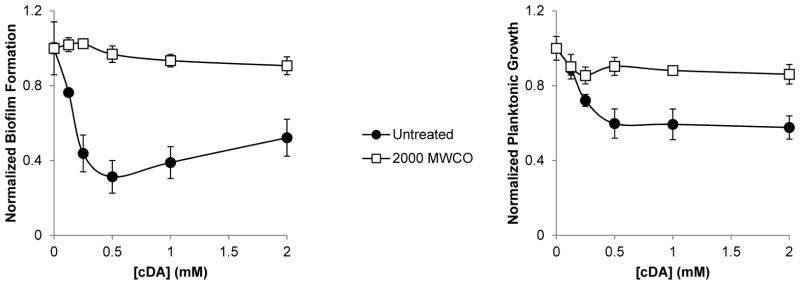

The small fatty acid cis-2-decenoic acid produced by P. aeruginosa has been previously reported to inhibit the formation and cause the dispersal of biofilms (Davies and Marques 2009). We tested the effects of CDA addition to A. tumefaciens biofilm assays. We found that the addition of 0.125 mM CDA was able to slightly inhibit biofilm formation and to a lesser extent planktonic growth of A. tumefaciens and that the addition of 0.5 mM CDA resulted in the highest degree of inhibition (Figure 7A and B). Unlike the biofilm inhibitory activity of the cell-free culture fluids, the activity of CDA was completely lost when this compound was dialyzed across a 2000 MWCO membrane (Figure 7A and B).

Figure 7. CDA has a dialyzable biofilm inhibitory activity.

A) acetic acid solubilized CV biofilm stain, measured as A600 and B) the planktonic growth, measured by OD600 prior to staining, from 48 h PVC 96-well plate A. tumefaciens biofilms. Increasing concentrations of CDA that was either untreated (closed circles) or dialyzed across 2000 Da (open squares) dialysis membrane into 4 liters of AT-N buffer were added to the biofilm assays. Values are normalized relative to cultures with no added CDA and are the means and standard deviations from three wells per condition.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provide evidence that P. aeruginosa produces a secreted inhibitor(s) of A. tumefaciens biofilm formation that functions predominantly or at least in part through stimulation of biofilm dispersal. Production of this inhibitor by P. aeruginosa is increased dramatically under iron-limited conditions. This increase occurs despite lower P. aeruginosa growth yields under iron limitation. Although it seemed reasonable that siderophores produced under iron limitation might inhibit A. tumefaciens biofilm formation through iron sequestration, the inhibition was not alleviated by high levels of exogenous iron. Nor was the inhibitory activity strongly regulated by the recognized P. aeruginosa iron-responsive regulatory systems, known quorum sensing systems, or mediated by known factors secreted by P aeruginosa

Competition for access to surfaces and for access to iron

The battery of secreted compounds produced by P. aeruginosa with biofilm dispersal activity suggests that, in its natural environment, P. aeruginosa likely competes for favorable surface environments with a diversity of other microorganisms (Irie et al. 2005; Bandara et al. 2010; Holcombe et al. 2010; Mowat et al. 2010; Pihl et al. 2010). Similarly, P. aeruginosa incurs the cost of producing a wide array of different siderophores to facilitate the cellular accumulation of the scarce amounts of iron to which it has access in aerobic environments. Such activity presumably provides a competitive advantage over other microorganisms in the same local environment (Poole and McKay 2003; Hibbing et al. 2010). These observations are consistent with fierce competition by P. aeruginosa for iron with S. aureus, and with Burkholderia spp. (Weaver and Kolter 2004; Mashburn et al. 2005).

Given the critical importance of iron to the metabolism of most organisms, it is not surprising that competitive behaviors are at least partially controlled by iron availability (Andrews et al. 2003). Indeed, while there is little work addressing the impact of iron on the regulation of antimicrobial factors, iron limitation is often used as a cue for virulence factor production, indicating that it can play a role in regulating antagonism between species (Ochsner et al. 2002). In this work, we have shown that iron limitation strongly promotes the release by P. aeruginosa of an inhibitor of A. tumefaciens biofilm formation. The addition of high concentrations of iron to A. tumefaciens biofilm assays in the presence of the active P. aeruginosa culture fluids had no effect on the inhibitory activity, suggesting that the active compound(s) does not act through iron sequestration. In addition to antagonizing the formation of A. tumefaciens biofilms when present throughout growth, we found that the addition of these culture fluids was able to disperse pre-formed biofilms. These data suggest that environmental iron levels play an indirect but potentially critical role in mediating the outcome of the competition between P. aeruginosa and A. tumefaciens, apparently by allowing P. aeruginosa to out compete A. tumefaciens for access to surfaces. Previous studies demonstrated that P. aeruginosa dominates biofilm formation in laboratory co-cultures with A. tumefaciens (An et al. 2006). The biofilm dispersal activity we have identified is likely to play an important part in this competitive superiority.

Iron limitation triggers a switch in the surface adherence and competitive behavior of P. aeruginosa

Prior studies suggest that iron plays an important role in the establishment, maturation, and dispersal of biofilms formed by P. aeruginosa. In flow cell biofilm conditions, the presence of iron was necessary for the formation of the large mushroom-like biofilms typically observed. Removal of iron by the addition of lactoferrin, a potent iron sequestering protein from mammals, resulted in the formation of relatively thin, flat biofilms (Singh et al. 2002; Singh 2004; Banin et al. 2005). Conversely, in static culture biofilms, the addition of micromolar concentrations of ferric or ferrous iron salts resulted in the inhibition and dispersal of P. aeruginosa biofilms (Musk et al. 2005). We also observed that the addition of iron to static P. aeruginosa biofilm assays resulted in the formation of less dense surface adhered biofilms but an increase in the amount of pellicle formation and planktonic growth. These data suggest that in iron limited static conditions, adherence to a solid surface is a favored state for P. aeruginosa growth. It is of particular note that the iron limited conditions that favor P. aeruginosa surface adherence are also the conditions under which the production of the inhibitor of A. tumefaciens biofilm formation was highest. This observation suggests that P. aeruginosa can inhibit biofilm formation and clear existing biofilms of competing organisms to improve access to a surface under the same conditions in which adherence is a favored mode of P. aeruginosa growth.

Production of the biofilm inhibitory activity is not strongly regulated by iron-responsive regulators or quorum sensing

Like many species of bacteria, P. aeruginosa employs the Fur protein to regulate its transcriptional response to cellular iron levels (Vasil and Ochsner 1999). In P. aeruginosa, the fur gene appears to be essential; however, viable missense mutants with aberrant iron-responsive behaviors, such as PAO1furC6Tc, have been isolated (Barton et al. 1996). P. aeruginosa also uses specific iron-responsive ECF σ-factors to control iron uptake, including pvdS which is responsible for controlling the production of the siderophore pyoverdine (Leoni et al. 2000). Surprisingly, deletion of pvdS and the furC6Tc missense mutation, both of which result in iron-insensitive flowcell biofilm phenotypes, had no appreciable effects on iron-stimulated production of the A. tumefaciens biofilm inhibitor(s). These data show that the iron-dependent regulation of inhibitor production is not controlled by the major iron-responsive regulators of P. aeruginosa.

P. aeruginosa uses a complex quorum sensing dependent regulatory system to control the expression of diverse biologically active compounds, and to mediate a stationary phase dominance phenotype over A. tumefaciens in co-culture [(An et al. 2006) and An et al. submitted)] These compounds can function alone or in combination to affect the physiology, behavior, and viability of competing organisms (An et al. submitted). We found that neither the quorum sensing-controlled effectors nor the quorum sensing systems themselves had any effect on the production of the inhibitory compound. This indicates that the previously observed dominance of P. aeruginosa in laboratory co-cultures with A. tumefaciens depends on a variety of diversely regulated P. aeruginosa factors including, but not exclusive to the dispersal promoting and biofilm inhibiting factor we report here.

The biofilm inhibitory factor is small, stable, and unlikely to be conferred by extracellular DNA, RNA, or proteins

To better understand the mechanism of biofilm inhibition and dispersal, and because of the potential importance and wide applicability of biofilm inhibitors, we attempted to examine the physical characteristics of the inhibitor. We showed that the inhibitory activity was stable over the course of extended storage, resistant to heat and UV-irradiation, and not degraded by nucleic acid or protein degrading enzymes suggesting that the inhibitory activity was the result of a bacterially produced small molecule. In addition, the complete loss of activity when the culture fluids were dialyzed across a 7000 MWCO membrane and partial loss of activity across a 2000 MWCO membrane suggest that the biofilm inhibitory activity may be the result of multiple small molecules, with molecular weights both greater and less than 2000 Da. However, none of the small molecules that have been shown to be produced by P. aeruginosa and to influence iron acquisition, biofilm formation or multi-species interactions appear to play a role in the observed inhibitory activity, with the exception of CDA (Boles et al. 2005; Irie et al. 2005; Glick et al. 2010; Davies and Marques 2009; An et al. Submitted).

A novel agent capable of inhibiting and dispersing A. tumefaciens biofilms

A biofilm dispersing activity from P. aeruginosa, now identified to be CDA, was initially observed to trigger the auto-dispersal of biofilms formed by P. aeruginosa as well as a wide range of microorganisms including the yeast Candida albicans (Davies and Marques 2009). Thus, we were interested to determine if the A. tumefaciens biofilm-dispersing activity in iron-limited P. aeruginosa culture fluids would be able to disperse P. aeruginosa biofilms. We observed that culturing static P. aeruginosa biofilms in the presence or absence of 50% (vol/vol) culture fluids from iron limited cultures had no observable effect on the accumulation of surface adherent biomass. The only condition we examined that altered P. aeruginosa biofilm formation was the presence of added iron, which greatly reduced the accumulation of surface adherent biomass. In contrast, the biofilm formation of A. tumefaciens was essentially eliminated in the presence of 50% (vol/vol) culture fluids, and severely compromised at much lower amounts. A concentration of as little as 1 nM synthetic CDA was shown to be sufficient to induce the dispersal of P. aeruginosa biofilms and the concentration of CDA in spent medium was measured at 2.5 nM (Davies and Marques 2009). Our results, showing that over 100 μM CDA is required for the inhibition of biofilm formation by A. tumefaciens and that the inhibitory activity of CDA was completely eliminated by dialysis, suggest that CDA is not the primary inhibitory compound in the cell-free culture fluids. In addition, there is no indication that CDA synthesis is stimulated under iron-limited conditions (D. Davies, personal communication). In fact, CDA is typically prepared from P. aeruginosa cultures grown in iron-replete media, whereas the primary activity that inhibits and disperses A. tumefaciens biofilms is strikingly elevated in iron-limited P. aeruginosa cultures (Davies and Marques 2009). Collectively, the lack of activity of the culture fluids against P. aeruginosa biofilms and the dialysis profile of the inhibitory activity suggest that we have identified a novel compound(s) produced by P. aeruginosa. The production of this compound is induced under iron limiting conditions, but the compound is distinct from siderophores, and is capable of efficiently inhibiting and disrupting A. tumefaciens biofilms.

Conclusions

Bacteria in the environment must compete with one another for scarce resources such as nutrients, including access to surface environments. We have found that batch cultures of P. aeruginosa grown in a defined medium produce a secreted factor(s) that is stimulated by iron-limitation, and inhibits A. tumefaciens biofilms. These same conditions also foster the formation of surface-adhered biofilms of P. aeruginosa. The biofilm inhibitory activity is clearly not the result of rhamnolipid production and appears to be distinct from CDA, thus likely representing a novel biofilm inhibitory activity. Future work will be directed towards identifying the chemical nature of the agent(s), its mode of action, and the regulatory basis for the iron-responsive production of the inhibitor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge Andrew Philips and Ying Cao for valuable input on this project. Matthew Parsek was particularly helpful providing strains of P. aeruginosa. Thomas Platt provided useful suggestions on the manuscript. M.E.H. was funded on the Indiana University Genetics, Molecular and Cellular Sciences Training Grant T32- GM007757. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1- GM080546 (C.F.) and through a grant from the Indiana University META-Cyt program funded in part by a major endowment from the Lilly Foundation (C.F.).

References

- An DD, Danhorn T, Fuqua C, Parsek MR. Quorum sensing and motility mediate interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Agrobacterium tumefaciens in biofilm cocultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3828–3833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511323103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews SC, Robinson AK, Rodriguez-Quinones F. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:215–237. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandara H, Yau JYY, Watt RM, Jin LJ, Samaranayake LP. Pseudomonas aeruginosa inhibits in vitro Candida biofilm development. BMC Microbiol. 2010:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banin E, Vasil ML, Greenberg EP. Iron and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11076–11081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504266102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton HA, Johnson Z, Cox CD, Vasil AI, Vasil ML. Ferric uptake regulator mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with distinct alterations in the iron-dependent repression of exotoxin A and siderophores in aerobic and microaerobic environments. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1001–1017. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.381426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berne C, Kysela DT, Brun YV. A bacterial extracellular DNA inhibits settling of motile progeny cells within a biofilm. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77:815–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles BR, Thoendel M, Singh PK. Rhamnolipids mediate detachment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from biofilms. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:1210–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckling A, et al. Siderophore-mediated cooperation and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2007;62:135–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson KC, Meyer JM, Dilworth MJ. Hydroxamate siderophores of root nodule bacteria. Soil Biology & Biochemistry. 2000;32:11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chipperfield JR, Ratledge C. Salicylic acid is not a bacterial siderophore: a theoretical study. BioMetals. 2000;13:165–168. doi: 10.1023/a:1009227206890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetser SE, Cloete TE. Biofouling and Biocorrosion in Industrial Water Systems. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2005;31:213–232. doi: 10.1080/10408410500304074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: A common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhorn T, Hentzer M, Givskov M, Parsek MR, Fuqua C. Phosphorus limitation enhances biofilm formation of the plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens through the PhoR-PhoB regulatory system. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:4492–4501. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.14.4492-4501.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies DG, Marques CNH. A Fatty Acid Messenger Is Responsible for Inducing Dispersion in Microbial Biofilms. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:1393–1403. doi: 10.1128/JB.01214-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar MA, Dandekar AM. Agrobacterium tumefaciens as an agent of disease. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:380–386. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman L, Kolter R. Genes involved in matrix formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 biofilms. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:675–690. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick R, et al. Increase in Rhamnolipid Synthesis under Iron-Limiting Conditions Influences Surface Motility and Biofilm Formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:2973–2980. doi: 10.1128/JB.01601-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbing ME, Fuqua C, Parsek MR, Peterson SB. Bacterial competition: surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:15–25. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcombe LJ, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa secreted factors impair biofilm development in Candida albicans. Microbiology-Sgm. 2010;156:1476–1486. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.037549-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie M, Ishiyama A, Fujihira-Ueki Y, Sillanpaa J, Korhonen TK, Toba T. Inhibition of the adherence of Escherichia coli strains to basement membrane by Lactobacillus crispatus expressing an S-layer. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;92:396–403. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horswill AR, Stoodley P, Stewart PS, Parsek MR. The effect of the chemical, biological, and physical environment on quorum sensing in structured microbial communities. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;387:371–380. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0720-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie Y, O’Toole GA, Yuk MH. Pseudomonas aeruginosa rhamnolipids disperse Bordetella bronchiseptica biofilms. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;250:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MA, et al. Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:14339–14344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036282100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi F, Archana G, Desai A. Siderophore cross-utilization amongst rhizospheric bacteria and the role of their differential affinities for Fe3+ on growth stimulation under iron-limited conditions. Curr Microbiol. 2006;53:141–147. doi: 10.1007/s00284-005-0400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko Y, Thoendel M, Olakanmi O, Britigan BE, Singh PK. The transition metal gallium disrupts Pseudomonas aeruginosa iron metabolism and has antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:877–888. doi: 10.1172/JCI30783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodkin-Gal I, Romero D, Cao S, Clardy J, Kolter R, Losick R. d-Amino Acids Trigger Biofilm Disassembly. Science. 2010;328:627–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1188628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewulak KD, Vogel HJ. Structural biology of bacterial iron uptake. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Biomembranes. 2008;1778:1781–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoni L, Orsi N, de Lorenzo V, Visca P. Functional analysis of PvdS, an iron starvation sigma factor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1481–1491. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1481-1491.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim B, Beyhan S, Meir J, Yildiz FH. Cyclic-diGMP signal transduction systems in Vibrio cholerae: modulation of rugosity and biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:331–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S, et al. Horizontal transfer of nonconjugative plasmids in a colony biofilm of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;255:115–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2005.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Gil M, Yousef-Coronado F, Espinosa-Urgel M. LapF, the second largest Pseudomonas putida protein, contributes to plant root colonization and determines biofilm architecture. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77:549–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashburn LM, Jett AM, Akins DR, Whiteley M. Staphylococcus aureus serves as an iron source for Pseudomonas aeruginosa during in vivo coculture. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:554–566. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.2.554-566.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt PA, Danhorn T, Fuqua C. Motility and chemotaxis in Agrobacterium tumefaciens surface attachment and Biofilm formation. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:8005–8014. doi: 10.1128/JB.00566-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowat E, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their small diffusible extracellular molecules inhibit Aspergillus fumigatus biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;313:96–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musk DJ, Banko DA, Hergenrother PJ. Iron salts perturb biofilm formation and disrupt existing biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chem Biol. 2005;12:789–796. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole GA, Kolter R. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:449–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner UA, Vasil AI, Johnson Z, Vasil ML. Pseudomonas aeruginosa fur overlaps with a gene encoding a novel outer membrane lipoprotein, OmlA. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1099–1109. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1099-1109.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner UA, Vasil ML. Gene repression by the ferric uptake regulator in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Cycle selection of iron-regulated genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4409–4414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner UA, Wilderman PJ, Vasil AI, Vasil ML. GeneChip((R)) expression analysis of the iron starvation response in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: identification of novel pyoverdine biosynthesis genes. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:1277–1287. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesci E, Pearson J, Seed P, Iglewski B. Regulation of las and rhl quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3127–3132. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3127-3132.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihl M, Davies JR, de Paz LEC, Svensater G. Differential effects of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on biofilm formation by different strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010;59:439–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt TG, Bever JD. Kin competition and the evolution of cooperation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2009;24:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K, McKay GA. Iron acquisition and its control in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Many roads lead to Rome. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2003;8:D661–D686. doi: 10.2741/1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey BE, Matthysse AG, Fuqua C. The FNR-type transcriptional regulator SinR controls maturation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens biofilms. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:1495–1511. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D, Webb JS, Kjelleberg S. Microbial colonization and competition on the marine alga Ulva australis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5547–5555. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00449-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rather PN. Swarmer cell differentiation in Proteus mirabilis. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:1065–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodionov DA, Gelfand MS, Todd JD, Curson ARJ, Johnston AWB. Computational reconstruction of iron- and manganese-responsive transcriptional networks in α-proteobacteria. PLoS Comp Biol. 2006;2:1568–1585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster M, Lostroh CP, Ogi T, Greenberg EP. Identification, Timing, and Signal Specificity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Quorum-Controlled Genes: a Transcriptome Analysis. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2066–2079. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2066-2079.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout JD, Chopp DL, Just CL, Hentzer M, Givskov M, Parsek MR. The impact of quorum sensing and swarming motility on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation is nutritionally conditional. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:1264–1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PK. Iron sequestration by human lactoferrin stimulates P. aeruginosa surface motility and blocks biofilm formation. BioMetals. 2004;17:267–270. doi: 10.1023/b:biom.0000027703.77456.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PK, Parsek MR, Greenberg EP, Welsh MJ. A component of innate immunity prevents bacterial biofilm development. Nature. 2002;417:552–555. doi: 10.1038/417552a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland IW. Biofilm exopolysaccharides: a strong and sticky framework. Microbiology. 2001;147:3–9. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempe J, Petit A, Holsters M, Montagu MV, Schell J. Thermosensitive Step Associated with Transfer of Ti Plasmid During Conjugation - Possible Relation to Transformation in Crown Gall. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:2848–2849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasil ML, Ochsner UA. The response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to iron: genetics, biochemistry and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:399–413. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verran J, Airey P, Packer A, Whitehead KA. Chapter 8 Microbial Retention on Open Food Contact Surfaces and Implications for Food Contamination. In: Allen I, Laskin SS, Geoffrey MG, editors. Adv Appl Microbiol. Academic Press; 2008. pp. 223–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson B, Currier TC, Gordon MP, Chilton MD, Nester EW. Plasmid required for virulence of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1975;123:255–264. doi: 10.1128/jb.123.1.255-264.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver VB, Kolter R. Burkholderia spp. alter Pseudomonas aeruginosa physiology through iron sequestration. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2376–2384. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.8.2376-2384.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg ED. Iron availability and infection. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-General Subjects. 2009;1790:600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitchurch CB, Tolker-Nielsen T, Ragas PC, Mattick JS. Extracellular DNA required for bacterial biofilm formation. Science. 2002;295:1487–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.295.5559.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.