Abstract

Objective

To evaluate an individually tailored multicomponent nonadherence treatment protocol using a telehealth delivery approach in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease.

Methods

Nine participants, age 13.71±1.35 years, completed a brief treatment online through Skype. Medication nonadherence, severity of disease, and feasibility/acceptability data were obtained.

Results

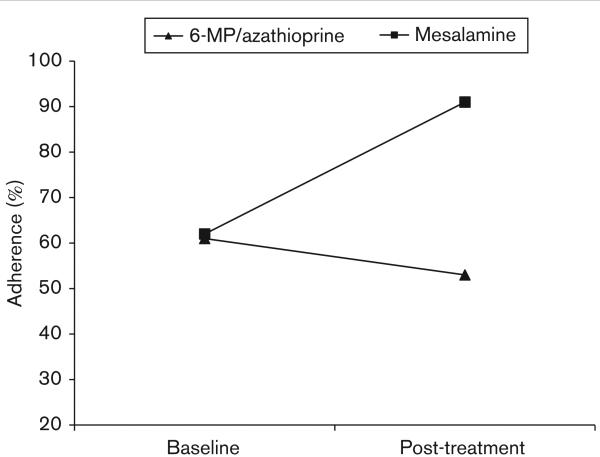

Adherence increased markedly from 62% at baseline to 91% for mesalamine (δ = 0.63), but decreased slightly from 61% at baseline to 53% for 6-mercaptopurine /azathioprine. The telehealth delivery approach resulted in cost savings of $100 in mileage and 4 h of travel time/patient. Treatment session attendance was 100%, and the intervention was rated as acceptable, particularly in terms of treatment convenience.

Conclusion

Individually tailored treatment of nonadherence through telehealth delivery is feasible and acceptable. This treatment shows promise for clinical efficacy to improve medication adherence and reduce costs. Large-scale testing is necessary to determine the impact of this intervention on adherence and health outcomes.

Keywords: adherence, compliance, inflammatory bowel disease, medication, pediatric

Nonadherence to treatment regimens is a major healthcare issue in the USA. There are numerous consequences to treatment nonadherence, including increased morbidity and mortality, additional complexity of clinical decision making by clinicians [1], and increased burden on the healthcare system, with an additional $100–300 billion in healthcare costs [2,3]. Medication adherence in pediatric chronic conditions is particularly challenging, with nonadherence prevalence rates ranging from 50% in children [1] to 65–88% in adolescents [4,5]. Indeed, in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the prevalence of medication nonadherence is 64% for immunomodulator therapy and 88% for mesalamine; the frequency of nonadherence (i.e. % of missed doses) is 38% for immunomodulators and 49% for mesalamine [5]. Moreover, there is evidence that IBD patients who are nonadherent to medications are 5.5 times more likely to relapse than those who are adherent [6].

Treatment of nonadherence in IBD is still nascent, although the available data suggest that behavioral interventions are promising and efficacious. We recently conducted a randomized-controlled trial of a group-based behavioral intervention to improve medication adherence in adolescents with IBD in which we observed a significant improvement in adherence over a 6-week treatment period (δ = 0.79) [7]. Using similar intervention components (e.g. behavior modification, problem-solving skills training, adherence monitoring), we tested an individually tailored treatment for nonadherence in adolescents with IBD to target family-specific barriers to treatment adherence. The results of this trial showed that treatment resulted in a 25% increase in medication adherence from baseline to after treatment (δ = 0.57) [8]. Thus, both group-based and individually tailored treatment approaches showed initial efficacy. However, both approaches also required weekly face-to-face visits for families, and these visits often occurred after school in the evenings. Consequently, ratings by both patients and parents for convenience of treatment were low in both trials. That is, although the treatment was beneficial, traveling each week to receive treatment was burdensome for patients and families.

To address this significant barrier to treatment engagement, we piloted a telehealth approach to delivery of the individually tailored multicomponent treatment protocol we had previously used [8] to treat medication nonadherence. This manualized protocol targeted educational, organizational, behavioral, and family psychosocial factors related to adherence. Our primary aim was to pilot test the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of this telehealth-based treatment approach and report data on cost savings of this model. Although we did not anticipate statistical significance of our findings, given the small sample size, we hypothesized medium effect sizes for improvement in medication adherence from baseline to after treatment, consistent with what we observed in the face-to-face trial. We further hypothesized that the treatment would show feasibility through treatment session attendance and acceptability, particularly in terms of convenience of treatment, through patient and parent ratings.

Methods

Participants

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, and all participants were recruited from the outpatient gastroenterology clinic. Participant eligibility criteria were determined through a medical chart review and included the following: (i) diagnosis of Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis (collectively IBD), (ii) age 11–18 years, (iii) currently prescribed 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP)/azathioprine and/or mesalamine, (iv) English fluency for the patient and at least one caregiver, and (v) access to the Internet. A recruitment letter was mailed to participants who fulfilled the eligibility criteria. Participants could opt out if they did not wish to be contacted for the study. The remaining participants were contacted over the telephone or approached during regularly scheduled outpatient gastroenterology clinic visits. Twenty-one patients who were eligible were sent recruitment letters. One patient opted out, seven could not be contacted, and four declined (one had family problems, one was too busy/not enough time, one did not perceive adherence as a problem, one had no interest in research). Thus, the final sample included the remaining nine participants who were enrolled and received treatment.

Study design

This was a single-arm pilot and feasibility clinical trial. Participants completed four assessment visits and four intervention sessions across ~5 months. Informed consent and assent were reviewed over the telephone and signed forms were sent to study staff through fax, email, or mail. Families were mailed baseline measures to complete at their convenience within a 1-week time frame. Participants mailed completed forms to study staff, and a follow-up telephone call was made once completed forms were received to carry out an assessment of disease severity and collect pill-count data over the telephone. Adherence was calculated from pill-count data. Beginning 2 weeks later, patients and their caregiver participated in weekly intervention sessions. Four weekly sessions, lasting ~60–90 min, were conducted online through Skype and webcam, and caregiver–patient dyads were seen independently, without other families present. Treatment providers were doctoral-level clinical psychologists or postdoctoral clinical psychology fellows; however, we have conducted similar trials with rigorously trained masters-level clinical psychology clinicians [7]. Although three different treatment providers were used in the trial, each patient was treated by the same clinician for the duration of their treatment. One week after the fourth intervention session, families were mailed post-treatment measures to complete and return in a 1-week time frame. Participants were provided modest compensation for their participation.

Measures

A demographic form including caregiver age, education, marital status, patient ethnicity, and annual household income was completed at baseline by the caregiver.

Pill count

Pill counts were carried out over the telephone at baseline and post-treatment assessment time points for 6-MP/azathioprine and/or mesalamine. Data were obtained from the patient's prescription bottles, including dosing instructions, date the prescription was filled out, quantity filled in prescription, and current number of pills.

Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index

The Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index [9] measures severity of disease in patients diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, and was administered at each assessment time point. The six-item measure is administered as an interview for patients and addresses abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, stool consistency, number of stools per 24 h, nocturnal stooling, and activity level. Total scores are a sum of all six items and range from 0 to 85, with a higher score reflecting a more active disease (i.e. 0–9 = inactive; 10–34 = mild; 35–64 = moderate; ≥ 65 = severe disease). The Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index is a reliable and well-validated measure; however, internal reliability was low (α = 0.53) in this study because of the small sample size.

Partial Harvey–Bradshaw Index

The Partial Harvey–Bradshaw Index [10] measures the severity of disease in patients diagnosed with Crohn's disease and was administered as an interview at each assessment time point. This three-item interview measures symptomology over the past 7 days. Questions address general well-being, abdominal pain, and number of liquid stools. Higher scores indicate a more active disease (i.e. 0 = inactive disease; 1–4 = mild disease; ≥ 5 = moderate-to-severe disease), with total scores ranging from 0 to 12 and calculated by summing all items. The internal consistency (α) was 0.86 for this study, indicating adequate reliability.

Feasibility Acceptability Questionnaire

The Feasibility Acceptability Questionnaire (FAQ) is a 22-item self-report questionnaire for a patient and caregiver developed specifically for the study to measure the feasibility and acceptability of online intervention components. Factors assessed pertain to the format, structure, convenience of treatment, etc. of the intervention. Each item is assessed on a seven-point Likert scale. The FAQ was completed independently by patients and parents at the post-treatment assessment.

Data analyses

Data analytic procedures were carried out using PASW 18.0 (IBM Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Data were entered and cross-checked for accuracy. Descriptive statistics (e.g. M, median, SD) were calculated for demographic, disease severity, adherence, and feasibility/acceptability variables. Heathcare cost savings were examined by calculating driving distance and minutes between patients’ homes and the hospital using Google maps. Mileage was multiplied by $0.555, which is the current Internal Revenue Service standard mileage rate for the cost of operating an automobile. Pill-count adherence was calculated as doses consumed/doses prescribed × 100. Missing pill count data (i.e. date of prescription refill) for one of the participants at post-treatment resulted in adherence data being calculated for eight of the nine participants. Examination of treatment effect (i.e. baseline to post-treatment change in medication adherence rates for 6-MP/azathioprine and mesalamine) was carried out using paired-sample t-tests. The magnitude of treatment effect was calculated using Cohen's δ effect sizes.

Results

Demographic, disease, and feasibility/acceptability parameters

In this study, six males and three females, age 13.71±1.35 years, were enrolled. Four of the nine patients were prescribed both 6-MP/azathioprine and mesalamine, and only two patients had a regimen that required only daily dosing. Eight participants reported their ethnicity as Caucasian and one reported her ethnicity as ‘other’. Parents were 46.08±5.86 years old, all were married, and 78% reported having at least a college degree. The median annual household income for families was $100 001–125 000. Of the seven patients with Crohn's disease, four had inactive disease and three had mild disease. One patient with ulcerative colitis had inactive disease and one had mild disease. Treatment feasibility was indicated by 100% treatment session attendance for all patients in the trial. Ratings on the FAQ by patients and parents are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive data for parent-report and patient-report forms of the Feasibility Acceptability Questionnaire

| Parent |

Child |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Rating in the ideal range | Mean rating | % Rating in the ideal range | Mean rating | |

| I liked the individualized formata | 100 | 6.67 | 56 | 4.67 |

| I thought the individualized format was helpfula | 100 | 6.56 | 67 | 4.56 |

| Amount of informationb | 89 | 4.33 | 100 | 4.33 |

| Treatment session lengthb | 89 | 4.67 | 67 | 5.22 |

| Number of sessionsb | 89 | 3.78 | 100 | 3.78 |

| Total time commitment for treatment (i.e. 4 weeks)b | 100 | 3.89 | 100 | 4.11 |

| I thought attending sessions was convenienta | 78 | 5.67 | 78 | 4.89 |

| I used the behavioral skills I learneda | 67 | 4.67 | 67 | 4.33 |

| Treatment helped improve my (child's) adherencea | 89 | 5.22 | 44 | 4.11 |

Ideal range is based on the assumption that ratings in this range represent a high degree of acceptability for respondents.

Ideal range = 5–7 on a seven-point Likert scale.

Ideal range = 3–5 on a seven-point Likert scale.

Evaluation of treatment effect

Table 2 provides raw data for each patient's medication regimen, baseline adherence, and post-treatment adherence. Paired-sample t-tests showed statistically nonsignificant differences between baseline and post-treatment adherence for either 6-MP/azathioprine (t = 0.48, P = 65) or mesalamine (t = – 1.27, P = 0.29). Examination of median adherence rates, used to account for the small sample size, showed that although 6-MP/azathioprine adherence decreased modestly (8% from 61% at baseline to 53% after treatment), there was a marked increase in mesalamine adherence (29% from 62% at baseline to 91% after treatment; Fig. 1). Observed effect sizes (δ) were – 0.17 for 6-MP/azathioprine and 63 for mesalamine.

Table 2.

Raw data for patient medication regimen and adherence

| Baseline |

After treatment |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of pills (6-MP) | Adherence (6-MP) | Number of pills (mesalamine) | Adherence (mesalamine) | Number of pills (6-MP) | Adherence (6-MP) | Number of pills (mesalamine) | Adherence (mesalamine) | |

| Patient 1 | 1.5 | 61.9 | 6 | 0 | 1.5 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Patient 2 | 1.5 | 39.39 | 1.5 | 100 | ||||

| Patient 3 | 1 | 16 | 1.25 | 67.2 | ||||

| Patient 4 | 1.5 | 16.24 | 1.5 | 45.24 | ||||

| Patient 5 | 1.25 | 65.31 | 1.25 | 18.85 | ||||

| Patient 6 | 1.5 | 86.9 | 2 | 92.86 | 1.5 | 78.79 | 2 | 90.91 |

| Patient 7 | 1 | 60.71 | 3 | 80.56 | 1 | 60 | 3 | 93.33 |

| Patient 8 | 0.25 | 100 | 3 | 42.54 | 0.25 | 0 | 3 | 91.36 |

| Patient 9 | 1 | 65.85 | 1 | a | ||||

6-MP, 6-mercaptopurine.

Could not be calculated because of missing data on the date of prescription refill.

Fig. 1.

Treatment effect on medication adherence. 6-MP, 6-mercaptopurine.

With respect to cost savings, the mean distance/patient/visit would have been 45.89 miles or 61.78 min traveling by automobile. This translated into per patient cost savings of $101.87 and 247.11 min of travel time over the course of treatment. The total cost savings across patients and course of treatment were $916.86 and 2224.00 min of travel time.

Discussion

This pilot clinical trial represents the first empirical evaluation of a telehealth application of treatment for medication nonadherence in IBD. Overall, the findings were very encouraging and suggest that a telehealth approach to individually tailored treatment for nonadherence is feasible, acceptable, and shows preliminary efficacy. Although there was a modest decrease in 6-MP/azathioprine adherence, we observed a considerable median increase of 29% in mesalamine adherence, with a medium effect size. This is consistent with our face-to-face intervention data [7,8], for which we have discussed plausible mechanisms of discrepant treatment effects across medications, including differences in regimen complexity. Nevertheless, with this being a consistent finding across studies, it may suggest that there is a particular barrier to 6-MP/azathioprine adherence that is unknown and the intervention is not currently designed to adequately address this. In addition to change in adherence, utilizing a telehealth model for treatment resulted in a per-patient cost savings of over $100 and more than 4 h of travel time over the course of treatment. Importantly, this calculation does not factor in other costs such as parking and loss of productivity because of time commitment. Further, this does not factor in long-term outcomes such as the extent to which healthcare resource utilization might decrease in those patients with improved medication adherence.

Our approach showed excellent feasibility, with 100% treatment session attendance across patients. Thus, patients and parents were able to log onto Skype and use it with minimal guidance, and treatment providers were able to build a rapport with patients and families well enough to keep them engaged in a virtual face-to-face treatment. Treatment acceptability ratings by patients and parents were highly favorable overall, with the vast majority providing ratings in the ideal range across factors. Most notably, ratings of convenience of treatment were high, with 78% of patients and parents providing ratings in the ideal range [8]. This highlights the utility and benefit of using a telehealth treatment model for this type of behavioral intervention. Applied in a clinical context, this telehealth model is advantageous in that it could be used to treat patients who are unable to travel to or from the hospital or clinic because of transportation, financial, time, health, or other constraints.

There were noteworthy methodological strengths in this trial that provide confidence in our findings. We used a manualized treatment protocol and fidelity checklists that ensured treatment protocol adherence and consistency across patients. In addition, we used a validated objective measure of medication adherence as the primary endpoint in evaluating treatment effect. We also examined several aspects of treatment acceptability in addition to feasibility, which provides a comprehensive view of the clinical utility of our telehealth approach as well as patients’ and families’ experience in the trial. Nevertheless, there are important limitations to this trial that warrant discussion. Because this was a pilot study, the sample size was small, which limited our ability to draw broader implications from our findings. However, our purpose was primarily to test the telehealth model and evaluate feasibility and acceptability and estimate effect size. In addition, our sample was restricted with respect to demographic diversity. Although IBD is a condition that disproportionately affects Caucasians, which consequently results in relatively high socioeconomic status, our sample was entirely Caucasian, mostly college educated, and had a relatively high annual household income. Finally, we were primarily interested in adherence to the two most common medications in pediatric IBD treatment. Thus, we are unable to discuss the potential for the impact of this treatment on other medications and supplements prescribed commonly such as prednisone, iron, calcium, and vitamin D.

Future research should focus on large-scale testing of telehealth adherence interventions. If found to be efficacious, this approach has the potential to optimize cost effectiveness, efficiency, and convenience for patients while allowing clinicians to provide a targeted intervention to improve outcomes. The effects of this intervention on other medications and supplements as well as other health outcomes such as health-related quality of life and disease severity is an important next step as well. Related to this, determining the barriers specific to 6-MP/azathioprine adherence will be critical to generalizing this treatment across adherence behaviors. One factor that will be important to assess is responsibility for treatment adherence, as differences in adherence across medications may be because of factors specific to the responsible individual (e.g. taste or size of medication may be a barrier for patients). Finally, continued clinical research that results in a refined approach to optimize the intervention by using the most effective components will be required to realize the full potential of this type of treatment.

Acknowledgements

Research was supported in part by PHS Grant P30 DK 078392, NIDDK K23 DK079037, and Institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award NIH/NCRR grant number 1UL1RR026314.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rapoff MA. Adherence to pediatric medical regimens. 2nd ed. Springer; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg JS, Dischler J, Wagner DJ, Raia JJ, Palmer-Shevlin N. Medication compliance: a healthcare problem. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27(Suppl):S1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiMatteo MR. The role of effective communication with children and their families in fostering adherence to pediatric regimens. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logan D, Zelikovsky N, Labay L, Spergel J. The illness management survey: identifying adolescents’ perceptions of barriers to adherence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28:383–392. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hommel KA, Davis CM, Baldassano RN. Objective versus subjective assessment of oral medication adherence in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:589–593. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kane S, Huo D, Aikens J, Hanauer S. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 2003;114:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hommel KA, Hente EA, Odell S, Herzer M, Ingerski LM, Guilfoyle SM, Denson LA. Evaluation of a group-based behavioral intervention to promote adherence in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:64–69. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834d09f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hommel KA, Herzer M, Ingerski LM, Hente E, Denson LA. Individually-tailored treatment of medication nonadherence. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:435–439. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182203a91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner D, Otley AR, Mack D, Hyams J, de Bruijne J, Uusoue K, et al. Development, validation, and evaluation of a pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index: a prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:423–432. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markowitz J, Grancher K, Kohn N, Lesser M, Daum F. A multicenter trial of 6-mercaptopurine and prednisone in children with newly diagnosed Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:895–902. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.18144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]