Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most common and debilitating health conditions in women in the United States and worldwide. Many women with MDD seek out complementary therapies for their depressive symptoms, either as an adjunct or alternative to the usual care. The purpose of this study is to understand the experiences of women with a yoga intervention in relation to their depression. The findings from this interpretive phenomenological study are derived from interviews with and daily logs by 12 women with MDD who took part in an 8-week gentle yoga intervention as part of a larger parent randomized, controlled trial. Results show that the women’s experience of depression involved stress, ruminations, and isolation. In addition, their experience of yoga was that it served as a self-care technique for the stress and ruminative aspects of depression and that it served as a relational technique facilitating connectedness and shared experiences in a safe environment. Future long-term research is warranted to evaluate these concepts as potential mechanisms for the effects of yoga for depression.

Keywords: yoga, depressive disorder- major, stress, rumination, connectedness

INTRODUCTION

Depression

Major depression is one of the most common and debilitating health conditions in adult women in the United States and worldwide (Branchi & Schmidt, 2011; Kessler et al., 2003). Major depressive disorder (MDD) and dysthymia are the most common forms of major depression, characterized by episodic or chronic sadness, anhedonia, and alterations in cognition and sleep (National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), 2009). Women have a disproportionately high incidence of depression, and many women with MDD or dysthymia report high levels of stress, ruminations, anxiety, and interpersonal difficulties (Marcus et al., 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2009). Unfortunately, the majority of individuals with depression are undertreated, and for those receiving the usual allopathic care for depression, relapse or recurrence rates can be up to 80% given that many women are non-adherent to the pharmacologic therapies because of intolerable side effects, cost concerns, and a lack of perceived benefit (Masand, 2003; Shim, Baltrus, Ye, & Rust, 2011). Therefore, research is warranted about complementary therapies such as yoga that may be feasible, acceptable, and effective for women with depression. In addition, studies that evaluate individuals’ experiences are valuable for providing insights into potential mechanisms of the effects of these therapies. The findings from this study are derived from a small sample of women who took part in the yoga intervention, as part of a larger mixed-methods, randomized, controlled trial designed to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and effects of yoga for women with confirmed moderate to severe depression despite the usual care.

Yoga Research

Adapted from an ancient holistic health system, yoga is a mainstream practice in the United States of particular interest to the mental health and complementary therapy research community. Yoga is currently one of the top 10 most practiced complementary modalities for health and well-being (Barnes, Bloom, & Nahin, 2009; Birdee et al., 2008). Recent surveys suggest that more than ten million Americans have practiced yoga at some point in their lives, purportedly for health promotion, for gentle physical activity, and for coping with stress and disease (Atkinson & Permuth-Levine, 2009; Birdee et al., 2008; Douglass, 2007; Saper, Eisenberg, Davis, Culpepper, & Phillips, 2004). Many styles of yoga exist, but Hatha yoga is one of the most commonly practiced and easily accessible forms in the United States and is the style of yoga used in this study (from this point forward referred to simply as “yoga”); it is a branch of yoga that combines breathing and physical and relaxation practices intended to facilitate the union of body and mind (Iyengar, 1976; National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), 2010).

Although there are numerous studies that describe measurable benefits of yoga for various populations, little is known about the actual experience of yoga by women with moderate to severe depression. Uebelacker and colleagues found that after an 8-week open trial of Vinyasa yoga most of the 11 depressed participants reported an emotional, physical, and social benefit to the yoga intervention (Uebelacker, Tremont et al., 2010). However, a description and close analysis of the stated benefits were not provided by the authors. Other qualitative studies have focused primarily on individuals who have physical illnesses, such as back pain, menopause, and diabetes, suggesting that yoga may be helpful for disease-related stress, depression, and anxiety (Alexander, Taylor, Innes, Kulbok, & Selfe, 2008; Atkinson & Permuth-Levine, 2009; B. E. Cohen et al., 2007; Galantino et al., 2004). Although relevant for an understanding of yoga, these studies do not provide full insight into women’s experiences of yoga as related to their depression.

Recently, there have been calls for closer qualitative evaluation of yoga and potential mechanisms of the effects for depression (Kinser, Goehler, & Taylor, 2012; Shim, Baltrus, Ye, & Rust, 2011; National Institutes of Health (NIH) & Bodeker, 2008; Institute of Medicine, 2009). Preliminary findings from research studies suggest that yoga may be effective for enhancing mood, yet the mechanisms for these effects are unclear (see the review article by Uebelacker, Epstein-Lubow et al., 2010). Qualitative investigations of participants’ experiences with yoga for depression may provide insights into these mechanisms as well as inform future research development. Given this, it was of particular interest to include qualitative methods in our parent randomized, controlled trial about yoga for women with moderate to severe depression to understand more fully women’s experiences with yoga, and to inform future studies.

METHODS

Design and Human Subjects’ Protection

This study is the qualitative arm of a larger community-based, prospective, randomized, clinical intervention study, which was conducted in a metropolitan area on the east coast of the United States. The University of Virginia Institutional Review Board (IRB) for Health Sciences Research reviewed and approved the study protocol, recruitment plans, and guidelines for the protection of confidentiality of participants. Written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to their enrollment in the study and verbal consent was obtained prior to audio-taping the participant interviews.

Sample

This study focuses on the 12 participants who completed an 8-week yoga intervention. We recruited this community-based sample of women with depression through IRB-approved recruitment materials (flyers and brochures) posted publicly as well as word of mouth and referrals from mental health providers in a city on the east coast of the United States. After an initial telephone screening, we conducted an in-person consent and screening visit with interested individuals. Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were adult women with a diagnosis of MDD or dysthymia as confirmed by the MINI Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) and moderate to severe depression as defined by a score of 10 or higher on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9). Potential participants were excluded if they were actively suicidal, had current psychosis or mania, had physical conditions making yoga difficult, had been hospitalized in the past month, had recent or expected changes in their antidepressant dosing, had a regular yoga or meditation practice longer than one month in the past five years, or were non-English speaking. Forty-eight women expressed interest in the larger study; 27 women were consented, enrolled in the study, and randomized to either a yoga group or an attention-control group. Twelve women completed the yoga intervention and were included in the sample for this qualitative arm of the larger parent study.

Data Collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews conducted with participants at the completion of the 8 week yoga intervention. Each interview lasted approximately 20 to 45 minutes and was audio recorded with participant permission. The interview began with a question about participants’ general perception of yoga, followed by open-ended questions on topics such as their impressions about the following: the impact of yoga on their mood throughout the study, usefulness of the home yoga practice, aspects of the intervention that they liked the most and/or least, what made participation in the intervention challenging or easy, and plans to continue yoga practice. Two participants requested to answer the questions via email because of prior travel plans. In addition, qualitative data about participants’ home yoga practice were collected through daily logs in which participants documented their feelings before and after daily home yoga practice as well as what directed their practice (e.g., DVD, using class handouts, or other). Data from the audiotapes, emails, and logs were transcribed into a de-identified word processing document for analysis.

Data Analysis

Data from the semi-structured interviews with participants were analyzed through a descriptive and interpretive phenomenological lens in order to discover how participants interpret their own experiences with depression and with the yoga. A phenomenological approach was most appropriate for this study, as it is based on the goal of describing a phenomenon completely with the hopes of finding themes in the participants’ experiences, with an awareness of the impact of the researcher’s subjective experience and biases (Cohen, Kahn, & Steeves, 2000; Giorgi, 2005; Thomas & Pollio, 2002). This methodology is not based on an imposed structure that the research brings to the data, but rather, focuses on participants’ interpretations of their experiences (Cohen, 2000; Agar, 1986). Strips of data were grouped into categories based upon similarities and these categories were them organized into themes. In the manner of a hermeneutic circle, we used a recurrent process of moving back and forth between categories and strips in allow for the emergence of the major themes which were subsequently examined and interpreted. The themes that arose were compared to the literature and were used to evaluate a coherent picture of participants’ experiences of depression and their participation in yoga.

A number of practices were used to enhance rigor and maintain ethical standards throughout the study. To ensure that the data analysis was logical and appropriate we used peer debriefing, in which colleagues unrelated to the study were asked to review strips of data and confirm themes. In addition, we have attempted to establish dependability of the data by clearly documenting decisions about methodology. Finally, we used bracketing as a technique to prevent presuppositions and assumptions that could alter data collection and analysis (Thomas & Pollio, 2002): briefly, we acknowledged assumptions about yoga’s importance in physical and mental wellness; although bracketing these assumptions would not eliminate them, it was important for maintaining openness to the data.

RESULTS

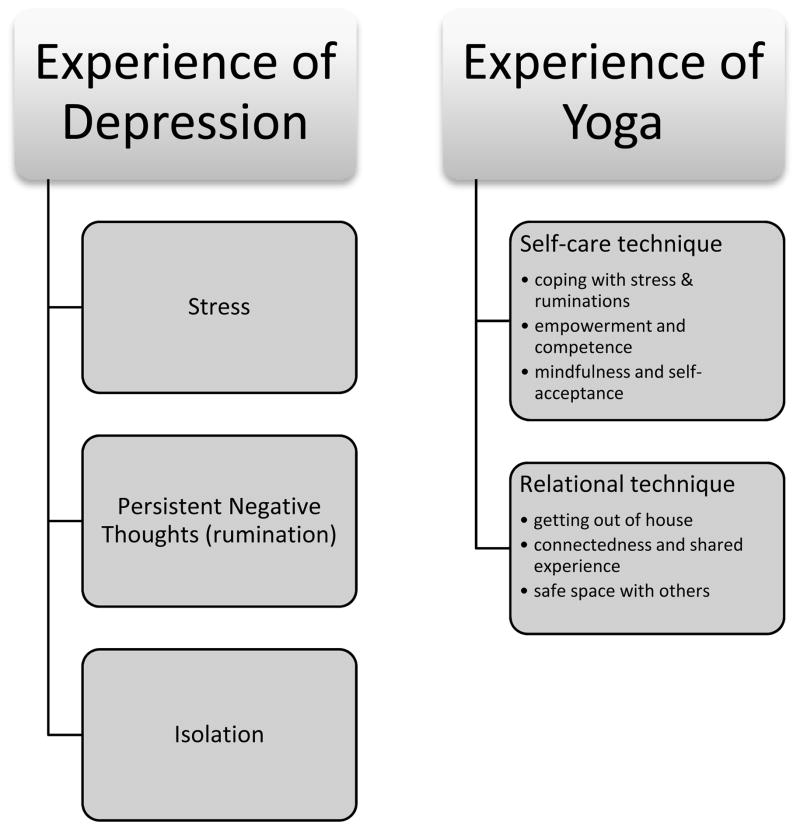

The participants consistently framed their experience of yoga within their specific experiences of depression. Before being able to talk about the yoga intervention, the participants consistently insisted on describing their specific experiences with depression. Two major themes arose from the interviews: (1) the experience of depression is that of stress, persistent negative thinking (ruminations), and isolation; and (2) yoga was beneficial as a self-care technique and as a relational technique, influencing key components of depression (see Figure 1). Quotes from participants are presented to support and illustrate these themes and sub-themes.

Figure 1.

Themes and sub-themes

Theme One: Experience of Depression

Three key components of depression permeated the discussion by participants about what bothers them most in their daily lives: stress, persistent negative thoughts (ruminations), and a sense of isolation. Participants commonly discussed the stressful nature of their lives and that persistent worrying about this stress was a major factor in their depression. The world was described as a generally stressful place, particularly because of busy work and home responsibilities. As one participant suggested, most people with depression and anxiety “don’t allocate time for themselves,” which can continue the cycle of stress. A busy lifestyle and persistent negative thinking seemed to trigger or worsen many participants’ depression, as one participant said: “I’m very busy, so I miss out on the day-to-day happiness because I’m so worried about the other stuff.” Self-judgment and feelings of anxiety seemed to pervade this persistent worrying in depression. One participant suggested that the majority of time “I am pessimistic about my abilities to do things. I get upset at myself when I don’t perform the way I think I should … judging myself is a major part of my depression.” She went on to suggest that these self-judging thoughts are “the trigger for my depression most of the time.” Another participant highlighted this sentiment, saying that “[f]or me, not thinking is a good thing. I shouldn’t think. I wouldn’t be so depressed if I didn’t think so much.” Depression also was described as an isolating experience. One participant suggested that she often experiences “a social phobic phase and rarely leave[s] home,” particularly when feeling extremely depressed. In addition, this isolation seemed to be a trigger for many participants’ depression. One woman stated that “If I’m not around people, that’s when I’m at my worst.” Many participants echoed this sentiment that there is a vicious circle of isolation, self-doubt, and worsening depression.

Theme two: positive experience with yoga

Sub-theme one: Yoga as self-care technique

When asked questions about the impact of yoga for their mood, most participants suggested yoga was beneficial because it provided a self-care strategy for the stressful and ruminative aspects of their depression. This important sub-theme is supported by participants’ suggestions that yoga is a self-caring technique because they: (a) learned methods for coping with stress and ruminations; (b) gained a sense of empowerment and competence; and (c) discovered self-acceptance.

Coping with stress and ruminations

Most participants stated that they perceived yoga to be beneficial because it allowed them to take the focus off of their persistent negative thoughts regarding the stress in their lives. One participant said that she liked to use yogic techniques to help her deal with daily stresses, as she stated: “It’s a mindfulness thing. When you’re being anxious and forget to breathe or are not mindful… yoga brings you back, you say ‘I’m going to breathe now and think about what’s really important.’” Many participants expressed that controlling stress in their lives was a constant uphill battle from which yoga provided an escape. One participant stated that yoga was helpful for “getting away from reality.” Another commented on the stressful nature of her world and the benefit of yoga, saying that “It helps more with my mood and my thoughts. I don’t have as much pressure when I’m in class. When I’m in the real world, there is a lot going on. In yoga class, I don’t have stress. I’m good.”

The practice of yoga seemed to help participants directly interrupt their typical patterns of persistent stressful thinking. This sentiment is reflected in one participant’s comment: “[With yoga] you’re focusing in on yourself and letting the world be out there, rather than your mind ticking away at things.” At the end of the study, another participant reported “I feel good about myself more often than before the yoga. I learned to focus on the positive, instead of what I did wrong, didn’t do, or can’t do anything about anyway.” As another example, a few participants reported that ruminations often prevented them from sleeping well and that they used the yoga techniques to assist with sleep. A participant stated that one of her most significant problems, prior to starting the yoga classes, was “being able to sleep through the night [because I was] not able to quiet my mind [and] I kept stressing out.” She was able to taper off her sleeping medications, as she reported that

Just doing some stretching and breathing before bed put me in a better mindset before bed and it allowed me to sleep… it’s amazing how much better you feel in all areas of your life when you’re able to relax and sleep … It really gave me control over that.… Before the study, [my doctors] had me on Trazadone to try to sleep, and I was really frustrated with the side effects … I didn’t like the way I felt on it or afterwards … now don’t have to take it at all, and I can calm myself, even throughout the day.

Participants repeatedly commented that they had “more manageable thoughts” after using yoga as an opportunity to “lay there peacefully… see the thoughts, let them go by without obsessing.”

It should be noted that for a few of the women the practice occasionally created a sense of disconnection or reinforced negative self-talk. One participant reported feeling mixed about the yoga classes because, although the classes made her “feel more hopeful and supported,” she still felt “self-conscious because I couldn’t get in some of the positions like the others did.” Some put pressure on themselves to be “standout student(s)” and berated themselves when they found that some aspects of the yoga intervention were difficult; one participant stated: “When I do things, I like to do them well, so that contributed … to feeling bad about myself although I was told whatever I could do was fine.”

Empowerment and Sense of Competence

Engaging in yoga seemed to be an empowering activity. Many participants suggested that yoga empowered them because it provided coping skills to gain a sense of control over their lives. One participant related a story of how, after weeks of yoga practice, she started to notice a general “feeling of being more capable” both in yoga class and in her everyday life. Another participant noted that the yoga classes helped her learn about herself which, in turn, gave her confidence to take better care of herself:

You gain that deeper connection with yourself. When you know yourself better, when you know your body and mind better, you start using them in healthier ways … like, if you’re in a bad relationship, you realize ‘this is not what I need.’ It helps you get stronger, in my opinion.

Other participants seemed to value this newly gained sense of inner strength, as indicated in their daily logs when they wrote comments such as “I feel accomplished” and “I’m glad I made myself do the work—I feel better.” An increased sense of control is reflected by the following comments written into a daily log after the participant completed her home practice: “Feel as if I have control over my life … detached from stresses; accepting of self in a more positive way.”

For some participants, the practice of yoga empowered them to engage in other activities beyond yoga: “It gives me motivation to try other things that I might not have tried before … it gave me a sense that ‘I can do it, I can do this for myself.’” Another participant stated that feeling successful with yoga helped prove to herself that she could try new things in other aspects of her life: “Part of my whole thing now is trying new things.… This is the new me.” Another participant commented that yoga helped her come to terms with her reality and empowered her to break patterns of self-judging thoughts: “I normally look at all the things I didn’t get done or do perfectly … but I learned to focus and be pleased with just doing a little something for me. I really took that to heart.”

Self-Acceptance

The participants seemed to value the yoga classes and home practice because it taught them to accept their current situation and practice yogic techniques that would best meet their needs. Participants found personalizing the practice according to their current mood was highly beneficial. Participants said that they valued the ability to be unique in their yoga practice, as one participant stated:

Yoga, it’s a beautiful practice. One thing that I … liked about yoga is the fact that doing it is called practice … which implies that it’s a unique experience for the individual … I enjoyed the peace and surrender that comes along with it and the philosophy behind it, about connecting with something that’s greater than yourself, whatever that may be for that individual.

Many of the women used the breathing and relaxation techniques to enhance a sense of calm or to impart energy. One participant suggested that when she was feeling anxious she found the breathing techniques helped her to calm down. Another stated that the breathing techniques helped her at any given time when faced by daily stresses: “I say to myself ‘ok, let me do some breathing’ to bring myself back so that I can calm down whatever is making me anxious or upsetting me.” Another participant wrote in her daily practice logs “I felt a little down & needed a boost- did some sun breaths- it bought me up” and “I was tired- did breath of joy- gave me quick needed energy.” Some participants experienced the value of moving the body to help depression; a participant said, “[with] generalized depression, focusing on the body and stretching and doing things that make you feel good is really important.” Physical movements seemed to have direct benefits for the mood, as one wrote in her log “love to do that child’s pose” and “I counted my breath and did gentle neck stretches—now feel rejuvenated, rested, energized” and “I love the mountain pose so it always makes me feel better.” An appreciation for the opportunity to focus on oneself and one’s needs was pervasive among participants, as many made statements similar to the participant who said that her favorite part of the study was “getting the time to be quiet and get inside.”

In addition, participants reported that part of self-acceptance was a cultivation of internal focus, which became a powerful way to deal with their depression. For example, one participant remarked on her perception of the benefit of the yoga intervention:

I got to have a deeper connection, mostly with myself. In yoga, the teacher said to get to know your body, what it needs today—that is really what yoga is about, helping your own body. I got to know what my body needed.

As another example of how yoga was an opportunity to focus on one’s inner experience and gain self-awareness, one participant wrote in her log that “This week has been about coming to grips with how deep my depression can be and how certain events very much trigger it. I did a lot of breathing work this week, just to maintain functionality.” By accepting themselves and their individual needs, participants were able to embrace yoga as a method for self-care. One participant seemed somewhat surprised by the outcome of yoga, stating “I didn’t expect to feel so great. I felt relaxed and happy because it was finally time to take care of myself.” Another participant stated:

I looked forward to knowing that Saturday at this time, it was time for myself to have a break. When your life is busy and fast paced, you don’t set time for yourself.… It was nice knowing that this time, this day, I’m going somewhere I want to be.

Participants acknowledged that self-acceptance and taking the time for self-care is essential for health, as one participant commented: “Every little thing you do for yourself counts. I haven’t had that in a very long time, so it’s very nice.”

Many participants also commented that they appreciated the teacher’s role in facilitating the personalized focus and encouraging them to practice yoga at their individual level. The teachers encouraged participants to create a yoga practice that worked for their current needs, as one participant suggested “We talked at the beginning [of class] about what was going on during our week and identified what we needed in class this week.” As another example, one participant stated:

I think that the instructors were good at looking at the individual as an individual and giving suggestions for them. If I couldn’t do something, I never felt anything negative, it was always like “if you need to make an accommodation, it’s your body and it’s good to get in-tune with it” … I appreciated [that] because it’s not the normal environment that I’m used to.

Another participant reflected upon the role of the yoga teacher, saying that she valued the support and constant reminders that “everybody does it to their own level of expertise.” Participants frequently commented that the yoga teachers reminded them to avoid self-judgment and be pleased with what they could do at this moment; one participant’s statement elucidates this:

At first, I was feeling bad that I couldn’t do the whole [home practice] all the time … and I really appreciated that [the teacher] said you could do 30 seconds today or an hour tomorrow, it’s great. It’s not about how much you didn’t do, it’s about how your yoga helped you today.

Participants consistently repeated this message from the teachers, as one participant put it, to “just do it the best way you can.”

Sub-theme two: Yoga as relational technique

Although many of the comments about the experience of yoga was focused on their internal experiences, the women in the study also consistently reflected upon yoga’s impact on their sense of isolation. Yoga seemed to become a relational technique, in that it allowed them to: (a) get out of the house; (b) gain a sense of connectedness and shared experience with others; and (c) have positive experiences in a safe space with others.

Getting Out of the House

For many, the opportunity to get out of the house and prove to themselves that they could follow-through on an activity was central to their experience in the study. One participant reflected that

Just showing up was good for me. Going somewhere without my husband was helpful for me. He would offer to drive but I could say ‘I think I can do it.’ Actually going and doing that was what’s good for me.

Many of the women echoed this participant’s statement that one of the benefits of a yoga class is the opportunity to get off the couch and do something different. Particularly because the experience of depression was often described in terms of isolation, the opportunity to leave their comfort zone was sometimes described as stressful but often discussed as being exhilarating and even freeing.

Connectedness and Shared Experience with Others

An additional benefit of the yoga classes was that they facilitated a sense of connectedness with others. In fact, most women gained a profound connection with others that even transcended conversation. One participant suggested that sharing a common experience did not require dialogue: “I also got a lot out of being around the other women. There was mutual support that seemed to emerge, even though we didn’t even always talk.” Simply being in the presence of other women and sharing a common experience was beneficial: “Class was nice because I was surrounded by others who were growing and experiencing the yoga at the same time that I was and going through the same [depression].” A sense of connection through shared experience was valuable and apparently beneficial for the mood, as one participant expressed her feelings in detail:

The shared experience was important … for coping … shared consciousness was there, when everyone was there together … it makes you feel a feeling of connectedness of everything.…You walk out of there feeling in touch with the condition of others, not just what’s going on with me, but what’s going on with everything, which is very reassuring. When you’re in a depressed state, you feel very alone … but feeling whole and part of a whole is where the value is really is.

Safe Space

For most of the participants, the support of the yoga teachers and the mutuality of the group provided a safe environment, which facilitated their sense of connectedness with others. There were positive rewards to joining together as a group, as described by the following comment:

We were all nervous, kind of like the first day of school, but [the teachers] were so welcoming and they created an environment where it was ok to make a mistake, so we all kind of relaxed and were able to work together as a group … It was a very positive social experience for something that is normally something very anxiety-provoking for me.

This safe environment was important for deepening their sense of self-care, as one participant stated: “It empowered me … it was safe to try … which is very helpful because with depression you feel so helpless, like you can’t do anything, and even if you try something it’s going to be wrong.” She continued this thought, suggesting that the sense of support was beneficial because it counteracted her sense of helplessness in “a safe atmosphere.” One participant felt personally motivated by this support of the teacher, as she said: “He made you feel good and that you weren’t this big awkward thing … you could still do this.” Another participant reflected upon the calming aspect of the actual physical space where they practiced yoga as a group: “The environment was good. The room is kind of like a womb with warm light and brown tones… Blankets everywhere, like being back in kindergarten and having nap-time— a time to relax.”

DISCUSSION

The qualitative findings from this study reveal that women’s experience of a yoga intervention must be framed first in their experience of depression. Depression was described being full of stress, ruminations, and isolation. Yoga, therefore, was beneficial in that it served as a self-care resource for mediating the effects of stress and ruminations and as a relational technique for getting participants out of the house and facilitating a sense of connectedness with others in a safe space. These findings support the quantitative results of the larger study in which there was a significant decrease in depression in the yoga group and that there was a strong trend towards decreased ruminations.

The experience of yoga by depressed women seemed to center largely on perceived changes in persistent negative thinking or ruminations. Individual differences in coping styles appear to be a key individual factor mediating the effects of stress and the recurrence of depressive episodes. For example, rumination is considered to be a maladaptive coping strategy, associated with the onset and duration of depression particularly in women (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2009; Uebelacker, Epstein-Lubow et al., 2010). Negative self-talk is common in women with depression and often reflects irrational thoughts about oneself (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2009). Participants’ insights into the impact of yoga on their negative self-talk and persistent negative thoughts suggest that a decrease in ruminations is an important mechanism for the effects of yoga on stress and depression.

We theorize that a number of combined factors may explain yoga’s specific impact on rumination. Because depressive states can lead to increased stress and ruminative thoughts about life stress, which in turn, can reinforce depression, the yoga intervention was designed to target this cycle (Hammen, 2006). First, yoga may help to target ruminations by enhancing mindfulness as a strategy for dealing with persistent negative thoughts about stress. Participants’ experiences with the yoga intervention revealed that they learned to develop a personalized coping strategy for stress and ruminations. Mindfulness is typically defined as the awareness of and attention to current experience with a sense of openness and acceptance (Bishop et al., 2004). The qualitative findings support that the encouragement to practice non-judgmental acceptance of depressive or stressful thoughts and focus on breathing or relaxation may have helped decrease ruminations (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010; Hardy, Roberts, & Hardy, 2009). Participants reported appreciating how the yoga teachers encouraged positive self-talk and self-acceptance, supporting previous studies suggesting that this may be helpful for women who have decreased self-confidence and negative ruminations (Uebelacker, Epstein-Lubow et al., 2010). Being mindful of and accepting particular needs or limitations was further reinforced when participants were taught to adapt their personal yoga practice according to the daily mood, using any tools (e.g., handouts, DVD) that appealed most to them. By encouraging mindfulness and offering a method to address the current mood, participants reported that their confidence increased as they progressed through the study. Physical activity can be highly effective at decreasing depression but it can be difficult for depressed individuals to immediately move into an active routine (Dunn, Trivedi, Kampert, Clark, & Chambliss, 2005; Larun, Nordheim, Ekeland, Hagen, & Heian, 2006; Tsang, Chan, & Cheung, 2008); the intervention was designed such that the yoga movements progressed in difficulty throughout the 8-week intervention, helping individuals feel more competent. The introduction of coping methods for dealing with maladaptive ruminations and for enhancing a sense of competence is imperative for diminishing symptoms of depression in women (Smith & Alloy, 2009).

A second factor that may have contributed to the effect on rumination and depression in the yoga group is the carefully designed sequences of breathing, physical practices, and relaxation practices. Participants were taught to adapt the practices to be either energizing or calming, depending upon their current affective state; for example, they were taught that if one feels particularly anxious or ruminative, it may be beneficial to start with an active breathing and physical practice and gradually progress to a slow, calming practice (Brown & Gerbarg, 2005a; Brown & Gerbarg, 2009; Weintraub, 2004). Studies suggest that breathing practices may have an influence on inflammatory processes involved in mood regulation and enhance parasympathetic responsiveness; thus, these practices may be helpful for decreasing depressive symptoms such as rumination (Brown & Gerbarg, 2005b; Kinser, Goehler, & Taylor, 2012; Oke & Tracey, 2009). Physical activity, even in a gentle form such as with yoga, may have antidepressant and anxiolytic effects, with some studies showing it to be as effective as pharmacologic and cognitive therapies (Mead et al., 2009; Netz & Lidor, 2003; Saeed, Antonacci, & Bloch, 2010; Streeter et al., 2007; Tsang, Chan, & Cheung, 2008). Depression is often associated with a cessation of awareness of the body and with excessive ruminations, so the manualized yoga intervention encouraged participants to be aware of sensation in specific parts of the body while in poses to facilitate integration the of mind and body and diminish ruminations (Jain et al., 2007; Uebelacker, Epstein-Lubow et al., 2010; Weintraub, 2004). Finally, classes ended with a guided meditation and relaxation practice, which may have been particularly important for decreasing stress reactivity (Benson, 1975; Gotlib & Hammen, 2009; Kinser, Goehler, & Taylor, 2012; Vempati & Telles, 2002).

Similarly, the findings from this study suggest that yoga may be beneficial for depression because it provides a resource for mediating the effects of stress. Yoga may be helpful for depression because it is a multi-modal management intervention for stress and rumination that encourages mindfulness and self-acceptance. The yoga intervention may have been beneficial to participants because it encouraged non-judgmental acceptance of depressive or anxious thoughts and introduced methods for regulating those thoughts; this non-judgmental practice of mindfulness may have allowed for a more positive self-talk and cognitive restructuring and, thus, a decrease in ruminations and depression (Hardy, Roberts, & Hardy, 2009; Hardy, Jones, & Gould, 1996). Mindfulness is generally defined as an open and accepting awareness of one’s current experience (Bishop et al., 2004; Salmon, Hanneman, & Harwood, 2010), and the cultivation of mindfulness is associated with decreased ruminations (Jain et al., 2007). Mindfulness is a “deceptively simple” skill that facilitates an individual’s non-judgmental focus on the present through awareness of cognitive and somatic states (Salmon, Hanneman, & Harwood, 2010). The relaxation and rhythmic breathing practices of yoga also may have helped decrease sympathetic nervous system activation typical in stress and depression, thus reinforcing participants’ appraisal of the benefits of yoga and decreasing rumination (Kinser, Goehler, & Taylor, 2012).

The yoga intervention seemed to enhance participants’ sense of self-confidence and competence, both in yoga and in life. Individuals often avoid situations that expose incompetence or that seem inconsistent with their sense of self (Banting, Dimmock, & Lay, 2009; Whaley, 2004; Yukelson, 2006); by helping participants feel good about themselves and practice yoga in a supportive environment, the intervention may have enhanced participants’ sense of competence. Because of the progressive nature of the yoga classes over eight weeks and the encouragement of participants to practice yoga in a way that met their individual needs, participants felt a sense of accomplishment and the experience of positive reinforcement of an improved affective state (Whaley, 2004). The yoga intervention seemed to have provided a method for controlling both somatic and cognitive stress associated with depression, with the result of not only decreasing ruminations but also improving the mood.

The findings in this study are consistent with the literature, which suggests that a yoga intervention may assist an individual with self-reflexivity. Participants repeatedly cited how empowered they felt by participating in the yoga class and that they carried this sense of empowerment and self-awareness with them through their daily lives. This self-reflexivity, or the turning of an individual towards oneself, may be important for depression, which is associated with a cessation of awareness of the body and excessive ruminations. Through yoga, an individual gains knowledge of inner feelings (e.g., “I feel good about myself”) through the outer actions (e.g., “I did child’s pose”). The experience of yoga is first and foremost through the body—the yoga participant brings herself from the stressful world “outside” into the inner womb-like environment of the class. The comments from participants demonstrated that the yoga class provided an “escape” from the stressful outside world, thus opening them to deeper experiences of inner well-being. The yoga practitioner seemed to engage in bodily movements and stillness, which ultimately lead to a discursive and embodied self-reflexive practice (Pagis, 2009). The discursive practice involved verbal and non-verbal interactions with fellow students and teachers, examining the self through interaction with others. As demonstrated in the case of one participant’s experience with suicidality and hospitalization, by engaging in yoga and with others, she was able to reflect upon and take care of her mental wellness. This is embodied self-reflexivity, or, as Merleau-Ponty suggests, “The body is the mirror of our being” (Merleau-Ponty, 1945 (2002)).

Research suggests that connectedness, or a sense of self in the world, is associated with mental wellness and motivation for self-care. Participants repeatedly cited how much they enjoyed sharing an experience with others. Although participants did value active engagement with others, our study’s findings suggest that there was an equal or greater benefit from the non-verbal “shared consciousness.” It has been suggested that this sense of connectedness is a more powerful mediator of depression than direct social support (Segrin & Rynes, 2009; Williams, 2006). By fostering positive group interactions and a sense of gratitude for self and others, the group yoga classes may have enhanced individuals’ sense of self and belonging in the world, which has been shown to increase motivation for self-care (Fredrickson, 2008; Lewis, 2008). Yoga may be an important method for enhancing the well-being of an individual through inter-connectedness with others (Iwasaki, 2007).

A sense of safety was an important element of many participants’ comments. Studies suggest that stimuli that enhance feelings of safety, such as the calming and soothing practices of yoga, may recruit neural circuits that support social engagement and inhibit defensive limbic activation (Porges, 2009). As an intentional therapeutic landscape, or a place perceived to have healing qualities, a yoga classroom is typically designed specifically to impart a sense of calm to those who enter (Andrews, Wiles, & Miller, 2004; Hoyez, 2007). Interestingly, the classroom was described as womb-like or kindergarten-like, perhaps suggesting that participants desired a return to childhood, when there was less isolation and presumably all needs were met. Indeed, depression is related to stressful life events, which may contribute to a sense of vulnerability, so it is not a surprise that the participants appreciated the sense of being cared for (Granek, 2006; Rhodes & Smith, 2010). Yoga may be an opportunity to “escape” reality and be enveloped in a safe, soothing practice and connection with others. This seems to suggest, too, that if yoga is practiced in the calm, quiet space of a classroom with the compassionate support of a teacher and classmates, then those same characteristics may be imparted to the yoga practitioner. In other words, the classroom became a space to find well-being, an “island of peace and serenity” in the midst of a stressful life (Hoyez, 2007).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the experiences of the women in the yoga intervention in a randomized clinical trial reflect that yoga provides a resource for mediating stress and controlling ruminations and facilitates a sense of connectedness with oneself and with others. The study highlights the women’s experience of the world as an isolating, busy, stressful place from which yoga may provide a safe respite. As a mechanism for providing moments of calm, self-focus, and connection in women with depression, yoga may serve a broad social need whereby individuals seek practices that heighten self-awareness and inner healing. The study is limited by its short-term nature and lack of long-term follow-up. Areas for future research abound with regards to exploring the concepts of rumination and connectedness in relation to mental wellness within the context of yoga. Future long-term research is warranted to evaluate these concepts as potential mechanisms for the effects of yoga for depression.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by grant number 5-T32-AT000052 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) at the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCCAM.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of interest:

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper

References

- Agar M. Speaking of ethnography. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(2):217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GK, Taylor AG, Innes KE, Kulbok P, Selfe TK. Contextualizing the effects of yoga therapy on diabetes management: A review of the social determinants of physical activity. Family & Community Health. 2008;31(3):228–239. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000324480.40459.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Wiles J, Miller K. The geography of complementary medicine: Perspectives and prospects. Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery. 2004;10:175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ctnm.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson NL, Permuth-Levine R. Benefits, barriers, and cues to action of yoga practice: A focus group approach. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2009;33(1):3–14. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.33.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banting LK, Dimmock JA, Lay BS. The role of implicit and explicit components of exerciser self-schema in the prediction of exercise behavior. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2009;10:80–96. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United states, 2007. National Health Statistics Reports. 2009;(12):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson H. The relaxation response. New York: Avon Books; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Birdee GS, Legedza AT, Saper RB, Bertisch SM, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. Characteristics of yoga users: Results of a national survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(10):1653–1658. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0735-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson N, Carmoda J, et al. Mindfulnes: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11(3):230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Branchi I, Schmidt M. In search of the biological basis of mood disorders: Exploring out of the mainstream. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(3):305–307. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RP, Gerbarg PL. Sudarshan kriya yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression: Part I-neurophysiologic model. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine. 2005a;11(1):189–201. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RP, Gerbarg PL. Sudarshan kriya yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression: Part II-clinical applications and guidelines. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine. 2005b;11(4):711–717. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RP, Gerbarg PL. Yoga breathing, meditation, and longevity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1172:54–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Kahn D, Steeves R. Hermeneutic phenomenological research: A practical guide for nurse researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen BE, Kanaya AM, Macer JL, Shen H, Chang AA, Grady D. Feasibility and acceptability of restorative yoga for treatment of hot flushes: A pilot trial. Maturitas. 2007;56(2):198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass L. How did we get here? The history of yoga in America, 1800–1970. International Journal of Yoga Therapy. 2007;17(1):35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, Kampert JB, Clark CG, Chambliss HO. Exercise treatment for depression: Efficacy and dose response. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. The science of subjective well-being. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2008. Promoting positive affect; pp. 449–468. [Google Scholar]

- Galantino ML, Bzdewka TM, Eissler-Russo JL, Holbrook ML, Mogck EP, Geigle P, Farrar JT. The impact of modified hatha yoga on chronic low back pain: A pilot study. Alternative Therapies in Health & Medicine. 2004;10(2):56–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Hammen CL. Handbook of depression. 2. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Granek L. What’s love got to do with it? The relational nature of depressive experiences. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2006;46(2):191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress generation in depression: Reflections on origins, research, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62(9):1065–1082. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Roberts R, Hardy L. Awareness and motivation to change negative self-talk. The Sport Psychologist. 2009;23(435):450. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy L, Jones G, Gould D. Understanding psychological preparation for sport: Theory and practice of elite performers. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 1996. Basic psychological skills; pp. 11–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyez A. The ‘world of yoga’: The production and reproduction of therapeutic landscapes. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(1):112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Integrative medicine and the health of the public: A summary of the February 2009 summit. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki Y. Leisure and quality of life in an international and multicultural context: What are major pathways linking leisure to quality of life? Social Indicators Research. 2007;82(2):233–264. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar BKS. Light on yoga. New York: Shocken Books; 1976. revised ed. [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Shapiro S, Swanick S, Roesch S, Mills P, Bell I, Schwartz G. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;33:11–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas K, Wang P. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R) Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(3):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, Goehler LE, Taylor AG. How might yoga help depression? A neurobiological perspective. EXPLORE: The Journal of Science and Healing. 2012;8(2):118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larun L, Nordheim LV, Ekeland E, Hagen KB, Heian F. Exercise in prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression among children and young people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;3:004691. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004691.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CS. Life chances and wellness: Meaning and motivation in the ‘yoga market’. Sport in Society. 2008;11(5):535–545. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus SM, Kerber KB, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg A, Balasubramani GK, Trivedi MH. Sex differences in depression symptoms in treatment-seeking adults: Confirmatory analyses from the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2008;49(3):238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masand P. Tolerability and adherence issues in antidepressant therapy. Clinical Therapeutics. 2003;25(8):2289–2304. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead G, Morley W, Campbell P, Greig C, McMurdo M, Lawlor D. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;3:CD004366. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty M. Phenomenology of perception. New York, NY: Routledge Classics; 1945 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) About yoga. 2010 Retrieved 9/26, 2010, from http://nccam.nih.gov/health/yoga/

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Women and depression: Discovering hope. NIH publication no. 09-4779. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health; 2009. Retrieved February 1, 2010, from www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/women-and-depression-discovering-hope/index.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) Bodeker G, editor. A public health research agenda for integrative medicine. 2008 Retrieved 9/26, 2010, from http://videocast.nih.gov/launch.asp?14504.

- Netz Y, Lidor R. Mood alterations in mindful versus aerobic exercise modes. Journal of Psychology. 2003;137(5):405–419. doi: 10.1080/00223980309600624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt LM. Gender differences in depression. In: Hammen CL, editor. Handbook of depression. 2. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 386–404. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3(5):400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oke SL, Tracey KJ. The inflammatory reflex and the role of complementary and alternative medical therapies. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1172:172–180. doi: 10.1196/annals.1393.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagis M. Embodied self-reflexivity. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2009;72(3):265–283. [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. The polyvagal theory: New insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2009;76(Suppl 2):S86–90. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76.s2.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes J, Smith J. “The top of my head came off”: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the experience of depression. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2010;23(4):399–409. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed SA, Antonacci DJ, Bloch RM. Exercise, yoga, and meditation for depressive and anxiety disorders. American Family Physician. 2010;81(8):981–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon P, Hanneman S, Harwood B. Associative/dissociative cognitive strategies in sustained physical activity: Literature review and proposal for a mindfulness-based conceptual model. The Sport Psychologist. 2010;24:127–156. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper RB, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Culpepper L, Phillips RS. Prevalence and patterns of adult yoga use in the United States: Results of a national survey. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2004;10(2):44–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C, Rynes KN. The mediating role of positive relations with others in associations between depressive symptoms, social skills, and perceived stress. Journal of Research in Personality. 2009;43(6):962–971. [Google Scholar]

- Shim R, Baltrus P, Ye J, Rust G. Prevalence, treatment, and control of depressive symptoms in the United States: Results from the national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES), 2005–2008. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2011;24(1):33–38. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.01.100121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JM, Alloy LB. A roadmap to rumination: A review of the definition, assessment, and conceptualization of this multifaceted construct. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(2):116–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streeter CC, Jensen JE, Perlmutter RM, Cabral HJ, Tian H, Terhune DB, Renshaw PF. Yoga asana sessions increase brain GABA levels: A pilot study. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine. 2007;13(4):419–426. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.6338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang HW, Chan EP, Cheung WM. Effects of mindful and non-mindful exercises on people with depression: A systematic review. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2008;47(Pt 3):303–322. doi: 10.1348/014466508X279260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uebelacker LA, Epstein-Lubow G, Gaudiano BA, Tremont G, Battle CL, Miller IW. Hatha yoga for depression: Critical review of the evidence for efficacy, plausible mechanisms of action, and directions for future research. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2010;16(1):22–33. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000367775.88388.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uebelacker LA, Tremont G, Epstein-Lubow G, Gaudiano BA, Gillette T, Kalibatseva Z, Miller IW. Open trial of vinyasa yoga for persistently depressed individuals: Evidence of feasibility and acceptability. Behavior Modification. 2010;34(3):247–264. doi: 10.1177/0145445510368845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vempati RP, Telles S. Yoga-based guided relaxation reduces sympathetic activity judged from baseline levels. Psychological Reports. 2002;90(2):487–494. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.90.2.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub A. Yoga for depression: A compassionate guide to relieve suffering through yoga. New York, NY: Broadway Books; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley DE. Seeing isn’t always believing: Self-perceptions and physical activity behaviors in adults. In: Weiss MR, editor. Developmental sport and exercise psychology: A lifespan perspective. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology; 2004. pp. 289–311. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KL, Renee V. Predicting depression and self-esteem from social connectedness, support, and competence. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2006;25(8):855–874. [Google Scholar]

- Yukelson DP. Communicating effectively. In: Williams JM, editor. Applied sport psychology: Personal growth the peak performance. 5. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2006. pp. 174–191. [Google Scholar]