Abstract

A modified protocol has been identified for Pd-catalyzed intermolecular aminoacetoxylation of terminal and internal alkenes that enables the alkene to be used as the limiting reagent. The results prompt a reassessment of the stereochemical course of these reactions. X-ray crystallographic characterization of two of the products, together with isotopic labeling studies, show that the amidopalladation step switches from a cis-selective process under aerobic conditions to a trans-selective process in the presence of diacetoxyiodobenzene.

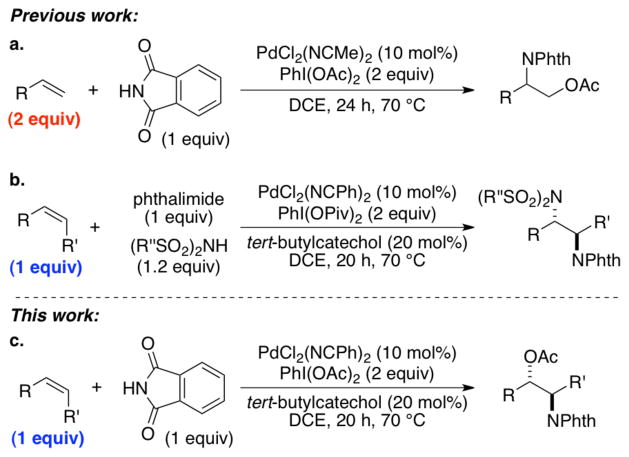

In recent years, a number of palladium-catalyzed methods have been reported for aminoacetoxylation1 and diamination2 of alkenes with diacetoxyiodobenzene [PhI(OAc)2] as the stoichiometric oxidant. These difunctionalization reactions are initiated by nucleopalladation of the alkene,3 followed by PhI(OAc)2-induced oxidative cleavage of the Pd–C bond, presumably via PdIII or PdIV intermediates.4 In 2006, Liu and Stahl reported a method for intermolecular aminoacetoxylation of terminal alkenes that employs two equivalents of alkene with respect to the nitrogen nucleophile (Scheme 1a).1b Recently, Martínez and Muñiz identified modified conditions that enabled regio- and diastereoselective intermolecular diamination of internal alkenes with the alkene as the limiting reagent (Scheme 1b).2c Here, we show that similar modified conditions are effective in intermolecular aminoacetoxylation reactions (Scheme 1c). In the course of this work, we obtained new mechanistic insights into the stereochemical course of these reactions, which prompted a reassessment of the originally proposed mechanistic pathway. The data show that PhI(OAc)2 can alter the stereochemical course of the aminopalladation pathway relative to aerobic oxidative amination reactions.

Scheme 1.

1,2-Difunctionalization of Alkenes

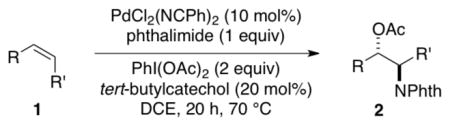

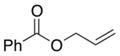

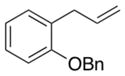

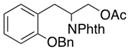

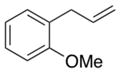

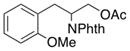

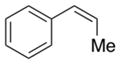

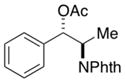

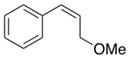

The catalyst conditions recently reported for diamination of alkenes (Scheme 1b2c) were used as a starting point to explore improved aminoacetoxylation conditions. Switching from PhI(OPiv)2 to PhI(OAc)2 as the oxidant enabled selectivity for aminoacetoxylation products (Scheme 1c). The scope of this reaction is similar to that observed for the diamination chemistry (Table 1). Representative terminal allyl ethers undergo the aminoacetoxylation in good yields (entries 1–4), as expected based on the earlier precedents. In addition, three allyl benzenes are successful (entries 5–7). These compounds are commonly difficult substrates in palladium catalysis, as they can undergo isomerization to the internal alkene in the presence of the palladium catalyst. Nevertheless, moderate yields could be obtained in the aminoacetoxylation reaction. Internal alkenes, such as (Z)-β-methylstyrene and (Z)-cinnamyl methyl ether, also undergo aminoacetoxylation without the formation of side products (entries 8–9). Only one diastereomer of the product is obtained.

Table 1.

Aminoacetoxylation of Alkenes

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | alkene | product | yield (%)a |

| 1 |

1a |

2a |

72 |

| 2 |

1b |

2b |

66 |

| 3 |

1c |

2c |

71 |

| 4 |

1d |

2d |

40 |

| 5 |

1e |

2e |

56 |

| 6 |

1f |

2f |

50 |

| 7 |

1g |

2g |

51 |

| 8 |

1h |

2h |

81 |

| 9 |

1i |

2i |

61 |

Isolated yield after chromatography

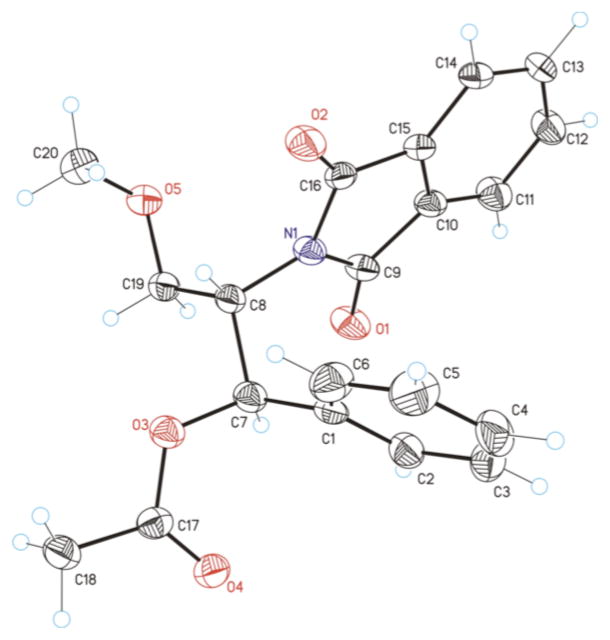

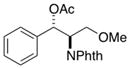

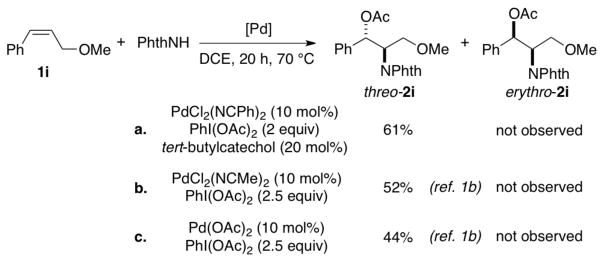

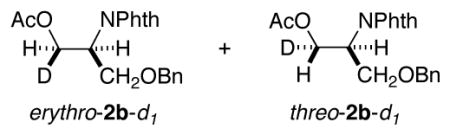

The relative stereochemistry of compound 2i was established by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis to be the threo isomer, and this product is formed exclusively under the optimized reaction conditions (Figure 1). 5 This stereochemical assignment is opposite to that proposed in the aminoacetoxylation reactions reported previously.1b The latter study proposed formation of erythro-2i on the basis of previously reported NMR characterization data for this compound.6 The single-crystal X-ray diffraction data reported here reveal that the NMR characterization data were inaccurate. Control experiments, summarized in Scheme 2, show that threo-2i is the sole aminoacetoxylation product obtained under several different catalytic conditions, including those from the original report by Liu and Stahl.1b The stereochemical course of these aminoacetoxylation reactions match that of the diamination reaction in Scheme 1b, which was similarly supported by X-ray crystallography.2c

Figure 1.

X-Ray Crystal Structure of threo-2i.

Scheme 2.

Exclusive formation threo-2i across related catalyst systems.

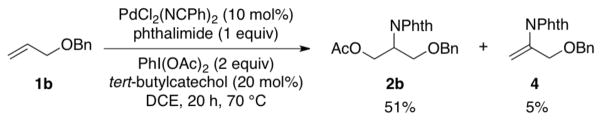

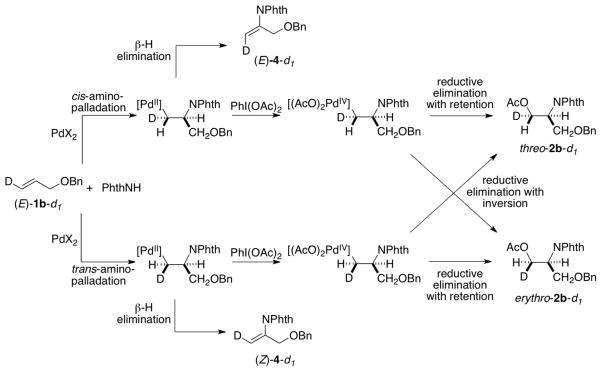

The relative stereochemistry of product 2i is controlled by the stereochemical course of the individual steps in the mechanism (Scheme 3). Following cis- or trans-aminopalladation of the alkene, oxidation of the Pd–alkyl species in the presence of PhI(OAc)2 is expected to generate a high-valent Pd–alkyl species that undergoes facile reductive elimination (for simplicity, the high-valent intermediate is illustrated as a PdIV species). This intermediate could undergo reductive elimination of the aminoacetoxylated product either by an SN2-type transition state with inversion of stereochemistry,7 or by a concerted three-centered transition state with retention of stereochemistry. 8, 9 Thus, threo-2i could be generated via cis-aminopalladation of the alkene and acetoxylation with retention of stereochemistry or trans-aminopalladation of the alkene and acetoxylation with inversion of stereochemistry.

Scheme 3.

Stereochemical Pathways for the Aminoacetoxylation of Substrate 1i.

Liu and Stahl previously tested the reactivity of substrate 1i under aerobic oxidation conditions [i.e., in the absence of PhI(OAc)2], and found that a Pd(OAc)2/O2 catalyst system converts 1i into Wacker-type amination product (Z)-3 in 20% yield (Scheme 4).1b The conversion of 1i to (Z)-3 rather than (E)-3 is indicative of a cis-aminopalladation pathway. No Wacker-type amination products are observed with 1i under the aminoacetoxylation conditions. Formation of product threo-2i via cis-aminopalladation implies that C–O reductive elimination proceeds with retention of stereochemistry, which has limited precedent.10

Scheme 4.

Oxidative Amination of Substrate 1i Under Aerobic Conditions (ref. 1b).

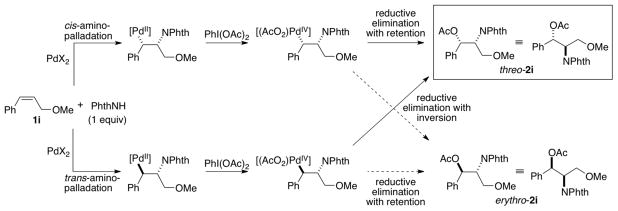

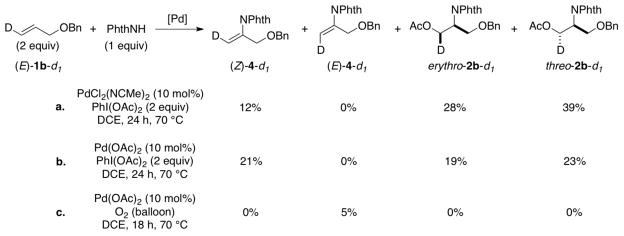

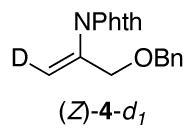

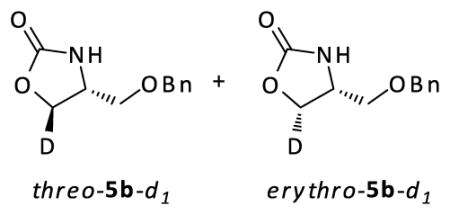

The identity of the oxidant [O2 vs. PhI(OAc)2] could influence the stereochemistry of the reactions, and we sought a substrate probe that could be used to assess the aminopalladation stereochemistry under aerobic vs. aminoacetoxylation reactions conditions. Fortuitously, substrate 1b yields a small amount of the Wacker-type amination product 4 under aminoacetoxylation conditions (Scheme 5). This result enables the use of deuterated substrate (E)-1b-d1 as a probe for the stereoselectivity of the aminopalladation step. Wacker-type oxidative amination could afford products (E)-4-d1 or (Z)-4-d1, and aminoacetoxylation could afford threo-2b-d1 or erythro-2b-d1,11 and the product identity can be used to gain insight into the stereochemical course of the reactions (Scheme 6).

Scheme 5.

Aminoacetoxylation of 1b Yields Wacker-Type Amination Byproduct 4.

Scheme 6.

Stereochemical Pathways for the Reaction of Deuterated Substrate (E)-1b-d1.

Use of substrate (E)-1b-d1 under aminoacetoxylation conditions yielded Wacker-type oxidative amination product (Z)-4-d1 and a diastereomeric mixture of aminoacetoxylation products threo-2b-d1 and erythro-2b-d1 (Scheme 7a-b). Formation of enimide (Z)-4-d1 is the product expected from trans-aminopalladation of the alkene. Since none of the cis-aminopalladation product (E)-4-d1 is detected, the mixture of aminoacetoxylation products is believed to arise from poor stereoselectivity in the reductive elimination of the primary alkyl–PdIV intermediate. The origin of this poor selectivity is not presently understood. 12 When substrate (E)-1b-d1 was subjected to aerobic conditions analogous to the aminoacetoxylation conditions (Scheme 7b vs. 7c), the oxidative amination product (E)-4-d1 was observed as the sole product [5% yield; 70% recovered (E)-1b-d1]. In spite of the poor yield, this product arises from a cis-aminopalladation pathway (cf. Scheme 6), consistent with the conclusion reached from the reaction of substrate 1i under aerobic conditions in the previous study (cf. Scheme 4).1b,13

Scheme 7.

Reaction of Deuterated Substrate 4-d1 Under Aminoacetoxylation and Aerobic Amidation Conditions.

Collectively, these results indicate that PhI(OAc)2 alters the stereochemical course of the aminopalladation step. Prior studies have shown that ligands play a critical role in modulating of nucleopalladation stereoselectivity.14 Most germane to the reactivity described here, Weinstein and Stahl recently demonstrated that Pd(TFA)2 exhibits greater proclivity for trans-aminopalladation relative to Pd(OAc)2 in Wacker-type oxidative amidation reactions.14d This trend can be rationalized by recognizing that substitution of an anionic ligand by an alkene in the trans-aminopalladation pathway will be more facile with less basic (i.e., less strongly coordinating) anionic ligands. Basic anionic ligands facilitate deprotonation of the amide nucleophile to afford a Pd–amidate intermediate that undergoes cis-aminopalladation of the alkene.15 In light of these considerations, we speculate that the Lewis acidic character of PhI(OAc)2 facilitates displacement of acetate from Pd(OAc)2 by the alkene and favors a trans-aminopalladation pathway.16,17

Conclusions

We have identified reaction conditions that enable the alkene substrate to be used as the limiting reagent in the aminoacetoxylation of terminal and internal alkenes. Furthermore, we have obtained evidence that PhI(OAc)2 influences the stereochemical course of Pd(OAc)2-mediated aminopalladation of alkenes, shifting the reaction from a cis- to a trans-selective process.

Experimental Section

General considerations

MS (ESI-LCMS) experiments were performed using a C8 (5 cm x 4.6 mm, 5 μm particles) column with a linear elution gradient from 100% H2O (0.5% HCO2H) to 100% MeCN in 13 min at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min.

General procedure for the aminoacetoxylation reaction (Table 1)

A Pyrex tube equipped with a stirrer bar is charged with 59 mg phthalimide (0.4 mmol, 1.0 eq) and 15 mg bis(benzonitrile)palladiumdichloride (0.04 mmol, 0.1 eq). Then, 0.6 mL of absolute dichloroethane are added via syringe and the solution is stirred at 70 °C for 1h. At this point, 260 mg iodosobenzene diacetate (0.80 mmol, 2.0 eq) and a previously prepared solution of 0.40 mmol of alkene with 14 mg of 4-tert-butylcatechol (0.08 mmol, 20%) are added. The resulting solution is sealed and stirred at 70 °C for 12h. After cooling to room temperature, the solution is washed with a 2%-solution of KOH (5 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (4 x 10 mL). The organic phases were combined, dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by chromatography (silica gel, neutralized with n-hexane/Et3N (3%) and then n-hexane/ethyl acetate, 3/1, v/v) to give the pure product.

3-Butoxy-2-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)propyl acetate (2a)

Obtained as colorless oil; 92 mg, 72% of yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 0.84 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H), 1.36–1.16 (m, 2H), 1.54–1.42 (m, 2H), 2.00 (s, 3H), 3.41 (dt, J = 9.3, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.48 (dt, J = 9.3, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (dd, J = 10.0, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (dd, J = 10.0, 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.62–4.44 (m, 2H), 4.73 (tdd, J = 8.2, 6.6, 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (dd, J = 5.5, 3.1 Hz, 2H), 7.86 (dd, J = 5.4, 3.1 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 13.8, 19.1, 20.7, 31.6, 50.2, 61.7, 67.3, 70.9, 123.3, 131.8, 134.0, 168.3, 170.6. IR ν(cm−1): 2958, 2932, 2871, 1743, 1709. HRMS: calcd for C17H21NO5Na: 342.1317, found: 342.1304.

3-(Benzyloxy)-2-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)propyl acetate (2b)

Obtained as colorless oil; 93 mg, 66% of yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.00 (s, 3H), 3.89 (dd, J = 9.9, 6.4 Hz, 1H), 3.98 (dd, J = 9.9, 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.64–4.44 (m, 4H), 4.86–4.73 (m, 1H), 7.42–7.13 (m, 5H), 7.74 (dd, J = 5.5, 3.0 Hz, 2H), 7.86 (dd, J = 5.4, 3.1 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 20.7, 50.2, 61.6, 66.7, 73.0, 123.4, 127.6, 127.7, 128.4, 131.8, 134.1, 137.6, 168.2, 170.6. IR ν(cm−1): 3063, 3031, 2950, 2871, 1741, 1707. HRMS: calcd for C20H19NNaO5: 376.1161, found: 376.1150.

3-Acetoxy-2-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)propyl benzoate (2c)

Obtained as yellow oil; 104 mg, 71% of yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.05 (s, 3H), 4.66 (dd, J = 6.9, 4.5 Hz, 2H), 4.75 (dd, J = 11.4, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 4.81 (dd, J = 11.4, 7.7 Hz, 1H), 4.90–4.96 (m, 1H), 7.41 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.55 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (dd, J = 5.4, 3.0 Hz, 2H), 7.88 (dd, J = 5.5, 3.0 Hz, 2H), 7.97 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 20.8, 49.7, 61.3, 61.9, 123.6, 128.5, 129.9, 131.7, 133.3, 134.4, 166.1, 168.1, 170.6. IR ν(cm−1): 3023, 2961, 2929, 1175, 1711, 1601. HRMS: calcd for C20H17NNaO6: 390.0954, found: 390.0936.

2-(1,3-Dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)-3-(octyloxy)propyl acetate (2d)

Obtained as yellow oil; 60 mg, 40% of yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 0.87 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.18–1.28 (m, 10H), 1.48–1.51 (m, 2H), 2.01 (s, 3H), 3.40 (dt, J = 9.3, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 3.49 (dt, J = 9.1, 6.4 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (dd, J = 10.0, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 3.93 (dd, J = 10.0, 8.3 Hz, 1H), 4.47–4.57 (m, 2H), 4.71–4.77 (m, 1H), 7.75 (dd, J = 5.5, 3.1 Hz, 2H), 7.87 (dd, J = 5.4, 3.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 14.2, 20.9, 22.8, 26.2, 29.3, 29.5, 29.6, 31.9, 50.3, 61.8, 67.4, 71.4, 123.5, 131.9, 134.2, 168.4, 170.8. IR ν(cm−1): 2926, 2855, 1776, 1710. HRMS: calcd for C21H29NNaO5: 398.1943, found: 398.1940.

2-(1,3-Dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)-3-phenylpropyl acetate (2e)

Obtained as colorless oil; 73 mg, 56% of yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.99 (s, 3H), 3.20 (dd, J = 13.9, 6.4 Hz, 1H), 3.36 (dd, J = 14.0, 10.0 Hz, 1H), 4.50 (dd, J = 11.3, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 4.62 (dd, J = 11.3, 9.3 Hz, 1H), 4.88–4.75 (m, 1H), 7.37–7.08 (m, 5H), 7.70 (dd, J = 5.5, 3.0 Hz, 2H), 7.79 (dd, J = 5.4, 3.1 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 20.7, 34.9, 51.8, 63.4, 123.2, 126.8, 128.6, 128.9, 131.6, 133.9, 136.8, 168.2, 170.6. IR ν(cm−1): 3062, 3028, 2927, 1771, 1707. HRMS: calcd for C19H17NNaO4: 346.1055, found: 346.1067.

3-(2-(Benzyloxy)phenyl)-2-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)propyl acetate (2f)

Obtained as yellow oil; 90 mg, 50% of yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.93 (s, 3H), 3.30 (dd, J = 7.8, 5.1 Hz, 2H), 4.47 (dd, J = 11.2, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 4.63 (dd, J = 11.3, 9.1 Hz, 1H), 4.93–4.99 (m, 1H), 5.06–5.12 (m, 2H), 6.75 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (dd, J = 7.4, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (td, J = 7.9, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.49 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.66 (dd, J = 5.5, 3.0 Hz, 2H), 7.74 (dd, J = 5.4, 3.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 20.8, 30.6, 50.5, 63.9, 70.2, 111.8, 120.8, 123.2, 125.8, 127.4, 127.9, 128.4, 128.6, 130.9, 131.8, 133.9, 137.2, 156.9, 168.3, 170.6. IR ν(cm−1): 3064, 3030, 2929, 2871, 1738, 1708. HRMS: calcd for C26H23NNaO5: 452.1474, found: 452.1474.

2-(1,3-Dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)-3-(2-methoxyphenyl)propyl acetate (2g)

Obtained as yellow oil; 76 mg, 51% of yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.98 (s, 3H), 3.19–3.28 (m, 2H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 4.48 (dd, J = 11.4, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 4.68 (dd, J = 11.4, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 4.90 (tdd, J = 9.3, 6.3, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (td, J = 7.4, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (td, J = 7.9, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (dd, J = 5.5, 3.0 Hz, 2H), 7.79 (dd, J = 5.4, 3.1 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 20.9, 30.5, 50.6, 55.3, 63.7, 110.4, 120.5, 123.2, 125.4 128.4, 130.9, 131.9, 133.9, 157.8, 168.4, 170.7. IR ν(cm−1): 3020, 2959, 2937, 1774, 1709. HRMS: calcd for C20H19NNaO5: 376.1161, found: 376.1168.

2-(1,3-Dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)-1-phenylpropylacetate (2h)

Obtained as a white solid; 105 mg, 81% of yield. m.p: 112–113 °C (CH2Cl2/hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.60 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 2.10 (s, 3H), 4.75 (dq, J = 9.1, 6.9 Hz, 1H), 6.30 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.14–7.21 (m, 3H), 7.33 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.62 (dd, J = 5.4 and 3.0 Hz, 2H), 7.69 (dd, J = 5.4, 3.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 15.3, 21.3, 50.4, 76.2, 123.2, 127.8, 128.4, 128.6, 131.6, 134.0, 137.5, 167.8, 169.9. IR ν(cm−1): 3035, 2984, 2927, 2854, 1770, 1704. HRMS: calcd for C19H17NO4Na: 346.1055, found: 346.1072.

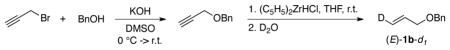

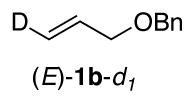

Synthesis of deuterated substrate probe (E)-1b-d1

A solution of KOH (2.69 g, 48 mmol) in DMSO (25 mL) was cooled in an ice bath and treated sequentially with benzyl alcohol (6.48 g, 60 mmol) and propargyl bromide (4.76 g, 40 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h at r.t. before being diluted with Et2O and H2O. The organic layer was separated, washed with H2O, dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. Flash chromatography afforded benzyl propargyl ether (5.07 g, 87 %).

The benzyl propargyl ether (1.46 g, 10 mmol) was treated with (C5H5)2ZrHCl (Schwartz reagent, 3.23 g, 12.5 mmol) in anhydrous THF (45 mL). After 10 min, the solution turned black, and the reaction was then quenched with D2O (7.4 mL), and stirring was continued overnight. The mixture was then diluted with Et2O, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated. The mixture was then purified by chromatography giving 1.26 g (86 %) of the product.

Compound (E)-1b-d1 is a known compound.18 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): d 7.30 (m, 5H), 5.96 (dtt, J = 17.2, 6, 1.6 Hz), 5.30 (dt, J = 17.2, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 4.53 (s, 2H), 4.03 (dd, J = 6, 4.4 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): d 138.3, 134.6, 128.4, 127.7, 127.6, 72.1, 71.1 (t, J = 1.9 Hz).

Procedures for the reaction of deuterated substrate (E)-1b-d1 (Scheme 7)

Stereochemical assignments of products (Z)-4-d1 and (E)-4-d1 were achieved from NOESY-1D analysis of 419 (see the supporting information). The stereochemical assignments of products erythro-2b-d1 and threo-2b-d1 were achieved after derivatization and 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis (see below and the supporting information).

(a) With PhI(OAc)2 as oxidant

In a dried glass tube, Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 (5.2 mg, 0.02 mmol, 10 mol %), PhI(OAc)2 (128.8 mg, 0.04 mmol, 2 equiv.), phthalimide (29.4 mg, 0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) were dissolved in DCE (0.25 mL), and then (E)-1b-d1 (59.6 mg, 0.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) was added. After the reaction mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 24 h, the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel with a gradient eluant of petroleum ether and ethyl acetate to afford (Z)-4-d1, erythro-2b-d1 and threo-2b-d1.

(b) With O2 as the oxidant

In a dried glass tube, Pd(OAc)2 (4.5 mg, 0.02 mmol, 10 mol %), phthalimide (29.4 mg, 0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) were dissolved in DCE (0.4 mL), charged with oxygen and then (E)-1b-d1 (59.6 mg, 0.4 mmol, 2 equiv.) was added. After the reaction mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 18 h, the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel with a gradient eluant of petroleum ether and ethyl acetate to afford (E)-4-d1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): d 7.88 (m, 2H), 7.75 (m, 2H), 7.27 (m, 5H), 5.65 (s, 1H), 4.53 (s, 2H), 4.36 (s, 2H).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): d 7.88 (m, 2H), 7.75 (m, 2H), 7.27 (m, 5H), 5.43 (s, 1H), 4.54 (s, 2H), 4.35 (s, 2H).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.98 (s, 3H), 3.87 (dd,J = 6.4, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 3.96 (dd, J = 80, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 4.48–4.57 (m, 3H), 4.74–4.81 (m, 1H), 7.24–7.28 (m, 5H), 7.71–7.74 (m, 2H), 7.83–7.85 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 20.7, 50.0, 61.2 (t, J = 22.4 Hz), 66.6, 72.9, 123.3, 127.6, 127.7, 128.3, 131.7, 134.0, 137.5, 168.2, 170.6. HRMS: calcd for C20H22DN2O5: 372.1664, found: 372.1668. IR ν(cm−1): 3088, 3063, 3031, 2868, 1740, 1708.

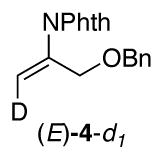

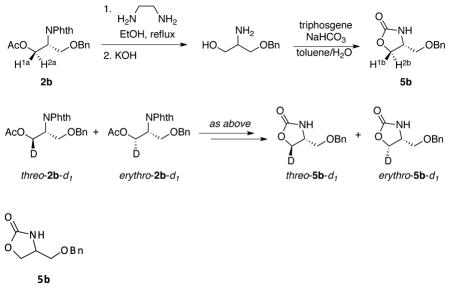

The structure of isomers erythro-2b-d1 and threo-2b-d1 were characterized by conversion to a heterocyclic product with diagnostic J-coupling and chemical shift differences. Protio-derivative 2b was converted to 5b20 to identify the chemical shifts of the two protons H1a and H2a. The chemical shifts of H1a and H2a were assigned based on the J-values in the 1H NMR spectrum of 5b in benzene-d6 (see figure S3 in the supporting information). 2b-d1 was similarly converted to 5b-d1, and the ratio of H1b : H2b corresponded to the ratio of isomers erythro-2b-d1 : threo-2b-d1 (see figure S4 in the supporting information).

1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) d 7.15 (m, 5H), 6.19 (br, s, 1H), 4.07 (s, 2H), 3.58 (dd, J = 8.7, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 3.46 (dd, J = 8.7, 5.3 Hz, 1H), 3.13 (m, 1H), 2.70 (m, 2H).

1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) d 7.15 (m, 5H), 6.26 (br, s, 1H), 4.07 (s, 2H), 3.56 (d, J = 8 Hz, 0.42H), 3.45 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 0.57H), 3.13 (dt, J = 6, 6 Hz, 1H), 2.75-2.67 (m, 2H).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

KM and CM thank the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (CTQ2011-25027) for financial support. The authors thank Dr. J. Benet-Buchholz, Dr. E. C. Escudero-Adán, Dr. M. Martínez-Belmonte and Dr. E. Martin for the crystal structure analyses. YW and GL thank National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21202185) for financial support. ABW and SSS thank the NIH (R01 GM067173) for financial support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information: 1H NMR spectra for stereochemical analyses; 1H and 13C NMR spectra of new compounds; X-ray crystallographic data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

Contributor Information

Shannon S. Stahl, Email: stahl@chem.wisc.edu.

Guosheng Liu, Email: gliu@mail.sioc.ac.cn.

Kilian Muñiz, Email: kmuniz@iciq.es.

References

- 1.Alexanian EJ, Lee C, Sorensen EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:7690–7691. doi: 10.1021/ja051406k.Liu G, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7179–7181. doi: 10.1021/ja061706h.For a related aminoetherification reaction, see: Desai LV, Sanford MS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:5737–5740. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701454.

- 2.(a) Iglesias A, Pérez EG, Muñiz K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:8109–8111. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Muñiz K, Kirsch J, Chávez P. Adv Synth Catal. 2011;353:689–694. [Google Scholar]; (c) Martínez C, Muñiz K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:7031–7034. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Zeni G, Larock RC. Chem Rev. 2004;104:2285–2309. doi: 10.1021/cr020085h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Beccali EM, Broggini G, Martinelli M, Sottocornola S. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5318–5365. doi: 10.1021/cr068006f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Minatti A, Muñiz K. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:1142–1152. doi: 10.1039/b607474j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kotov V, Scarborough CC, Stahl SS. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:1910–1923. doi: 10.1021/ic061997v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Jensen KH, Sigman MS. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:4083–4088. doi: 10.1039/b813246a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) McDonald RI, Liu GS, Stahl SS. Chem Rev. 2011;111:2981–3019. doi: 10.1021/cr100371y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For leading references, see: Canty AJ, Denney MC, Skelton BW, White AH. Organometallics. 2004;23:1122–1131.Dick AR, Kampf JW, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12790–12791. doi: 10.1021/ja0541940.Powers DC, Ritter T. Nat Chem. 2009;1:302–209. doi: 10.1038/nchem.246.Deprez NR, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:11234–11241. doi: 10.1021/ja904116k.Powers DC, Lee E, Ariafard A, Sanford MS, Yates BF, Canty AJ, Ritter T. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:12002–12009. doi: 10.1021/ja304401u.Powers DC, Ritter T. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:840–850. doi: 10.1021/ar2001974.Muñiz K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9412–9423. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903671.Hickman AJ, Sanford MS. Nature. 2012;484:177–185. doi: 10.1038/nature11008.

- 5.Additionally, single crystal X-ray analysis of 2h also established the relative stereochemistry to be threo, which suggests a unified pathway for internal alkenes (see the supporting information for details).

- 6.Fles D, Majhofer B, Kovac M. Tetrahedron. 1968;24:3053–3057. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sibbald PA, Rosewall CF, Swartz RD, Michael FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15945–15951. doi: 10.1021/ja906915w.Iglesias Á, Álvarez R, de Lera AR, Muñiz K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:2225–2228. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108351.Reductive elimination from PdIV–alkyl complexes with inversion of stereochemistry is also supported by analogy to fundamental studies of PtIV–alkyl complexes: Williams BS, Goldberg KI. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2576–2587. doi: 10.1021/ja003366k.Stahl SS, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:2182–2192. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980904)37:16<2180::AID-ANIE2180>3.0.CO;2-A. and references therein.

- 8.Byers PK, Canty AJ, Crespo M, Puddephatt RJ, Scott JD. Organometallics. 1988;7:1363–1367. [Google Scholar]

- 9.For examples of discrete PdII complexes in which oxidative cleavage of a PdII–C bond may proceed with either inversion or retention of stereochemistry, see: Coulson DR. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:200–202.Wong PK, Stille JK. J Organomet Chem. 1974;70:121–132.Bäckvall JE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977;18:467–468.Bäckvall JE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;19:163–166.Zhu G, Ma S, Lu X, Huang Q. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1995:271–273.

- 10.Desai LV, Hull KL, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9542–9543. doi: 10.1021/ja046831c.For a relevant precedent involving Csp3–O reductive elimination from PtIV, see: Khusnutdinova JR, Newman LL, Zavalij PY, Lam YF, Vedernikov AN. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2174–2175. doi: 10.1021/ja7107323.

-

11.Substrate (E)-1b-d1 also avoids the complication associated with potential reversible β-hydride elimination leading to a more thermodynamically favored product rather than the diagnostic alkene isomer. For example, substrate 1i could exhibit this complication, as depicted below (we thank Prof. Datong Song, University of Toronto, for drawing our attention to this potential complexity):

- 12.The poor diastereoselectivity observed for reductive elimination of aminoacetoxylation product erythro- vs. threo-2b contrasts the excellent stereoselectivity observed for reductive elimination of aminoacetoxylation product threo-2i (cf. Scheme 3) and products derived from other internal alkene substrates. Presumably, the different selectivity is associated with the different reactivity of secondary benzylic vs. primary aliphatic alkyl–Pd intermediates.

- 13.A similar analysis of cis- vs. trans-aminopallation has been employed in the aminoetherification reaction in ref. 1c.

- 14.For discussion of the factors that contribute to nucleopalladation stereoselectivity, see reference 3f and Nakhla JS, Kampf JW, Wolfe JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2893–2901. doi: 10.1021/ja057489m.Liu G, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6328–6335. doi: 10.1021/ja070424u.Keith JA, Henry PM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9038–9049. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902194.Weinstein AB, Stahl SS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:11505–11509. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206702.

- 15.For further analysis of anionic ligand effects in amidopalladation reactions, see: Ye X, Liu G, Popp BV, Stahl SS. J Org Chem. 2011;76:1031–1044. doi: 10.1021/jo102338a.Ye X, White PB, Stahl SS. J Org Chem. 2013;78:2083–2090. doi: 10.1021/jo302266t.

- 16.NMR spectroscopic analysis of solutions of Pd(OAc)2 and PhI(OAc)2 did not provide evidence for a ground-state interaction between these species, but this result cannot exclude a kinetic effect in which iodine(III) facilitates displacement of acetate by an alkene.

- 17.Reactions between phthalimide and PhI(OAc)2 could afford hypervalent iodine–phthalimide adducts, such as PhI(OAc)(NPhth) and PhI(NPhth)2; however, it is not clear how the formation of such species would alter the stereochemical course of amidopalladation of the alkene. For references describing species such as PhI(OAc)(NPhth) and PhI(NPhth)2, see the following: Hadjiarapoglou L, Spyroudis S, Varvoglis A. Synthesis. 1983:207–208.Kim HJ, Kim J, Cho SH, Chang S. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16382–16385. doi: 10.1021/ja207296y.Moriyama K, Ishida K, Togo H. Org Lett. 2012;14:946–949. doi: 10.1021/ol300028j.

- 18.Yagi K, Oikawa H, Ichihara A. Biosci Biotech Bioch. 1997;61:1038–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 19.4 is a known compound: Rogers MM, Kotov V, Chatwichien J, Stahl SS. Org Lett. 2007;9:4331–4334. doi: 10.1021/ol701903r.

- 20.Product 5b is a known compound. The 1H NMR was consistent with the data in the literature: Bégis G, Cladingboel DE, Jerome L, Motherwell WB, Sheppard TD. Eur J Org Chem. 2009:1532–1548.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.