Abstract

Background

Despite the advantages of using high schools for conducting school-based Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) programs for adolescent substance misuse, there have been very few studies of brief interventions in these settings.

Objectives

This multi-site, repeated measures study examined outcomes of adolescents who received SBIRT services and compared the extent of change in substance use based on the intensity of intervention received.

Methods

Participants consisted of 629 adolescents, ages 14 to 17, who received SBIRT services across 13 participating high schools in New Mexico. The level of service received and number of sessions were collected through administrative records, while the number of self-reported days in the past month of drinking; drinking to intoxication; and drug use were gathered at baseline and 6-month follow-up.

Results

Brief Intervention (BI) was provided to 85.1% of adolescents, while 14.9% received brief treatment or referral-to-treatment (BT/RT). Participants receiving any intervention reported significant reductions in frequency of drinking to intoxication (p<.05) and drug use (p<.001), but not alcohol use, from baseline to 6-month follow-up. The magnitude of these reductions did not differ based on service variables. Controlling for baseline frequency of use, a BT/RT service level was associated with more days of drinking at 6 month follow-up (p<.05), but was no longer significant when controlling for number of service sessions received.

Conclusions and Scientific Significance

These findings support school-based SBIRT for adolescents, but more research is needed on this promising approach.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol and drug use among adolescents is a world-wide problem.1–3 In the US, adolescent alcohol and drug use is prevalent, with one in ten youth ages 12–17 reporting past month use of illicit drugs and 18.1% reporting binge drinking within the past month.4 Early age of onset of alcohol and drug use is associated with negative health and social outcomes.5–7 Although intervention studies to reduce alcohol and drug use among adolescents can be conducted in specialized alcohol and drug treatment settings,8 the vast majority of at-risk adolescent users do not seek and are not enrolled in specialty treatment services,4 indicating that alternative approaches are needed. One approach that is becoming more widely used with adults and is promising for adolescent populations is screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT). The rate of positive drug screens using a common survey instrument (the CRAFFT)9 for substance abuse among 12-to-17 year-olds has been found to range from 8–24% in ambulatory health settings and up to 29.5% in schools,10 underscoring the potential utility of providing SBIRT in these settings.

There is a limited but growing body of random assignment studies comparing brief interventions (BI) with treatment-as-usual for alcohol and drug-using adolescents in various settings. Findings have been mixed. For example, in a randomized trial conducted in an emergency department, adolescents ages 13–17 who received a brief motivational intervention reported lower frequency of alcohol use and heavy drinking at 12-month follow-up compared with adolescents who received standard care.11 Likewise, a recent clinical trial in an emergency department found that a brief intervention was effective in reducing aggression and alcohol-related consequences.12 However, a randomized study testing a brief computerized intervention for alcohol misuse among injured adolescents treated in an emergency department found that the intervention was no better than standard care.13 Other studies have examined brief interventions for adolescents delivered in primary care. A multisite random assignment study found office-based brief interventions to be ineffective in reducing alcohol use compared to standard care.14 And a small randomized pilot study of brief intervention in primary care with 42 at-risk teenagers found preliminary evidence for the effectiveness of the brief intervention in reducing marijuana use.15 Schools are promising venues for universally screening adolescents for alcohol and drug use problems. School-based SBIRT has the advantage of being highly accessible to students.7 Additionally, there is a large population of high school students whose alcohol and drug use does not yet rise to the level of abuse or dependence, but whose use could easily escalate to become problematic, making them potentially good candidates for BIs. Despite the obvious appeal of using schools for SBIRT interventions, there have been very few studies of brief interventions in high schools. A pilot random assignment study in Los Angeles suggested that implementing screening and brief intervention was feasible in a high school (in that almost half of the invited students participated in the intervention), but the sample size (N=18) was too small to detect significant changes in behaviors from baseline to the 3-month follow-up.16 To date, the only other random assignment study of BI conducted in a school17 was a 3-arm randomized trial with 79 12-to-17 year-olds referred for alcohol or illicit drug problems that did not rise to the level of dependence. Two brief MI sessions without parental involvement were compared with one session involving both the parent and the adolescent vs. an assessment-only control group. At 6-month follow-up, both interventions were superior to assessment only in reducing number of days drinking, binge drinking and using drugs, as well as the consequences of their use.

In 2003, the U.S. Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) invested significantly in the expansion of SBIRT in healthcare settings in 7 states. The evaluation of this national initiative, described elsewhere,18 was focused mainly on adults and did not present results for adolescents under age 18. The present study utilizes administrative and program evaluation data from the adolescent SBIRT Program in New Mexico, led by the nonprofit organization Sangre de Cristo Community Health Partnership (SDCCHP). SDCCHP implemented SBIRT in over 35 school- and community-based settings throughout New Mexico. Thus, the present study adds to the very small extant body of literature on BIs in school-based settings for adolescent substance use. It does so using a relatively large sample of students who received school-based SBIRT as delivered in actual clinical practice, in one of over a dozen communities in a large southwestern state.

The aims of the present study are to: (1) describe the design and implementation of school-based SBIRT; (2) examine outcomes of adolescents who received SBIRT services; (3) investigate the extent of differential change in substance use behaviors based on the intensity of intervention received; and (4) examine the relationship between substance use outcomes and service variables.

METHODS

Clinical Intervention

SBIRT was provided to adolescents from May 10, 2005 through May 5, 2008 in school-based health clinics throughout New Mexico. Services were delivered by 15 Behavioral Health Counselors (BHCs) who were integrated into 13 school-based health clinics (12 high schools and 1 middle school). Some BHCs covered two school sites located within their service area.

Initially, the program was designed such that the school-based health center staff conducted universal screenings for all students seen in its clinics for any reason. A demographic questionnaire, a question which asked “Are you concerned about a family member’s use of alcohol or drugs?”, and the CRAFFT,19 a brief questionnaire to identify adolescents at risk for drug or alcohol problems, were administered. The CRAFFT was used as both a screening tool and to inform clinical decisions regarding level of care. The mnemonic CRAFFT questionnaire consists of six yes/no questions: (1) “Have you ever ridden in a Car driven by someone (including yourself) who was high or had been using alcohol or drugs?” (2) “Do you ever use alcohol or drugs to Relax, feel better about yourself or fit in?” (3) “Do you ever use alcohol or drugs while you are Alone?” (4) “Do you ever Forget things you did while using alcohol or drugs?” (5) “Do your Family or Friends ever tell you that you should cut down on drinking or drug use?” and (6) “Have you ever gotten into Trouble while you were using alcohol or drugs?”

Initially, school-based health center staff reviewed the CRAFFT and made a direct referral to the on-site BHC for those who screened positive. Early in the course of the project it became apparent that integration into the health centers was not uniform across sites. At most schools, the process worked very well, yielding a large number screened and referred to the BHC. At several sites, however, the number of completed screenings and referrals to the BHCs was quite low, likely due to a combination of student concerns about confidentiality and discomfort among health center staff. In these cases the screening and recruitment procedures were revised, such that BHCs handed out the questionnaires to students in the classrooms and reviewed the scoring criteria directly with the students as a group. Students were informed that their responses would remain confidential and would not be shared with school staff or their parents. The BHCs then collected the completed forms and privately arranged for BIs directly with some of the students, based on their responses.

As a rough guideline supplied by SAMHSA, students scoring 1–4 on the CRAFFT were considered eligible for a BI, while students scoring 5 or higher were eligible for brief treatment (BT) or referral-to-treatment (RT) at one of the specialty treatment providers with whom SDCCHP had established memoranda of agreement for the purposes of the SBIRT initiative. Ultimately, however, the appropriate level and frequency of services was a clinical decision determined by the BHC after speaking with the student.

The BHCs, all Master’s level clinicians, received a uniform 80 hour training curriculum on intervention strategies and project procedures. Senior clinical supervisors monitored the BHCs and reviewed cases twice a month, providing booster training annually and as needed. The brief intervention based on motivational interviewing,20 with the goal of helping the student to weigh the costs and benefits of substance use and increase motivation for behavior change, including for participating in treatment if clinically appropriate. The Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (ACRA)21 was used as the basis of the BT level of care. The goals of ACRA include promoting abstinence, engagement in rewarding pro-social activities, the formation of positive peer relationships, and improving family relationships. Parental consent was not necessary for students 14 years and older because New Mexico allows 14-year-olds to consent to behavioral health treatment, and the evaluation was not conducted as research but as grantee performance monitoring required by SAMHSA.

Data and Sample

The present study was granted an exemption from review by the Friends Research Institute’s Institutional Review Board because the data were archival data collected by SDCCHP staff during implementation of the service project and were de-identified by SDCCHP prior to analysis by researchers from Friends Research Institute. The Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) Questionnaire was used, as required by SAMHSA, for demographics and outcome data. Demographic data only were collected for students who received screening. Data on substance use patterns in the last 30 days were collected for students who screened positive (scoring at least 1 on the CRAFFT) and received at least one service session with the BHC, while those who received BT completed the full GPRA. Every fourth student who received an intervention service was flagged for a 6-month follow-up interview using the GPRA as part of the SAMHSA-required SBIRT evaluation. Follow-up interviews were conducted by the BHCs, who reminded students that their responses were confidential.

The current study focuses on the subsample of adolescents ages 14–17 who were part of the SBIRT evaluation follow-up pool. The baseline and 6-month follow-up data for adolescents were linked with treatment records maintained by the BHCs. These records included the number of service sessions delivered and the level of intervention actually received (as opposed to services planned, regardless of whether they were received).18

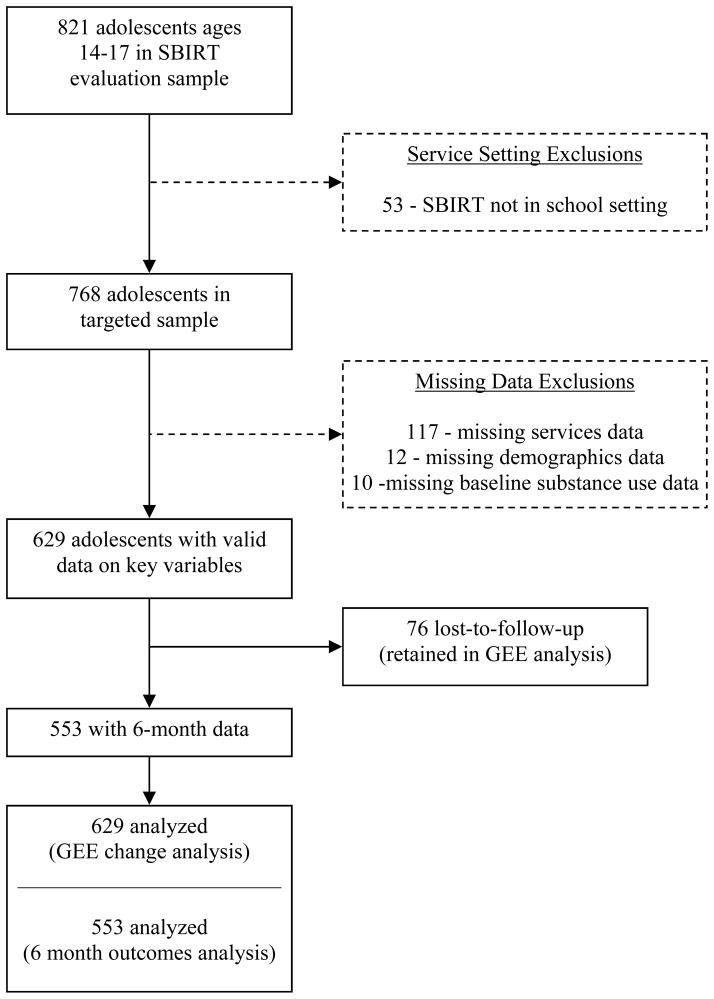

A total of 9,835 screenings were administered at the 13 school sites over the course of the project, with 3,569 students screening positive on the CRAFFT. Of those tracked for follow-up, complete data on demographic characteristics, baseline substance use behaviors, and services received were available for N=629 adolescents. Six-month follow-up data were available for 87.9% of these cases. Participants were paid $20 for completing the 6-month follow-up assessment. Figure 1 shows a data flow diagram for the study. There were no significant baseline differences in days of drug use (p=.70), alcohol use (p=.26), or drinking to intoxication (p=.13) between students who were lost to follow-up (n=76) and students who were successfully interviewed at 6 months (n=553). Comparing the final analysis sample to the larger sample of adolescents who were not part of the evaluation sample but were eligible for SBIRT services, there were no differences on age, Hispanic ethnicity, race, baseline days of drinking, or baseline days of alcohol intoxication. However, the analysis sample had slightly higher representation of females (50.2% vs. 56.0%; p<.01).

FIGURE 1.

Analysis sample data flow.

Measures

The following measures were drawn from the GPRA and the service records of the SDCCHP BHCs, and are operationalized as follows:

Demographics

Demographic variables included age (in years), gender, and Hispanic ethnicity. A dummy series was created to represent race, including American Indian/Alaska Native and Other/multiple races, with White as the reference category.

Frequency of Substance Use

These three variables, assessed at baseline and again at 6-month follow-up, included the self-reported number of days in the past 30 days that the student: (1) used any illicit drugs (including use of non-prescribed psychotropic pharmaceuticals), (2) used alcohol, and (3) was intoxicated from alcohol.

Change from Baseline to Follow-up

A binary variable was created to capture Interview Time Point (0=baseline; 1=6-month follow-up).

Services Received

Information on services received for each student was collected through regular administrative case reporting by the SDCCHP BHCs. A binary variable was created to indicate the level of intervention received (0=BI alone; 1=BT/RT), while a continuous variable was created that showed the number of service encounters with each adolescent patient.

Statistical Analysis

The analyses of change in substance use over time and based on service delivery variables were conducted by Generalized Estimation Equations (GEE) with unstructured correlations and robust standard errors. Due to the distribution of the three outcome variables, the GEEs were specified with the negative binomial family and log link function. GEE analyses estimated the overall population-averaged magnitude of change in each outcome from baseline to follow-up, and whether change in substance use frequency over time differed by service level. Dependent variables included the number of days of illicit drug use, days of alcohol use, and days of drinking to intoxication in the past 30 days, all of which were assessed at baseline and repeated at 6-month follow-up. Demographic characteristics (gender, age, race, and ethnicity) were used as control variables. The between-subjects factor was Service Level (BI vs. BT/RT), while the repeated factor was Interview Time Point (baseline vs. 6-month follow-up). Their interaction gauged the extent of differential change as a function of service level. This analysis made use of all available data, including cases lost to follow-up.

The analysis was also conducted with subsamples of adolescents who were determined to be at risk and reported past 30 day use of drugs (n=200), alcohol (n=265), and drinking to intoxication (n=231) at baseline, in order to evaluate the extent of change in substance use frequency for this potentially higher-risk group who reported recent use at baseline. Separate analyses were also conducted to examine the effect of number of service encounters within each service level (BI and BT/RT) using similar models that included Number of Service Sessions interacted with Time in lieu of Service Level.

In addition to the analysis of relative change, analyses were conducted examining the number of days of use of drug and alcohol and drinking to intoxication at 6 month follow-up for each of the three outcomes. Negative binomial regression was used, controlling for the baseline value of the dependent variable and demographics. Service variables were entered as predictors in a two step fashion, controlling for service level (BI vs. BT/RT) in the first step, and adding service sessions in the second step.

RESULTS

Patient Sample

Characteristics of adolescents in the SDCCHP follow-up sample, stratified by level of intervention received (BI; BT/RT), are shown in Table 1. Most adolescents who received SBIRT services got BI only (85.1%), while 14.9% received BT or RT. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between students who received BI and students who received BT/RT in terms of gender, race, or Hispanic ethnicity. Adolescents who received BT/RT were slightly younger than those who received BI only (M=15.7 v. 15.4, p<.05).

TABLE 1.

Demographic, substance use, and service differences among adolescents who received brief intervention (BI) or brief treatment/referral to treatment (BT/RT).

| BI (n=535) | BT/RT (n=94) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Demographics*

|

|||

| Female Gender, Percent | 50.47 | 48.94 | .82 |

| White, Percent | 92.34 | 88.30 | .34 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN), Percent | 6.36 | 9.57 | |

| Other race/multiple races, Percent | 1.31 | 2.13 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity, Percent | 81.68 | 74.47 | .12 |

| Age, M(SD)

|

15.67 (1.03) | 15.41 (1.06) | .03 |

|

Substance Use (baseline)*

|

|||

| Number of days of illicit drug use in last 30 days, M(SD) | 3.54 (8.15) | 8.76 (11.92) | <.001 |

| Number of days of alcohol use in last 30 days, M(SD) | 1.46 (3.21) | 3.01 (4.83) | .003 |

| Number of days of alcohol intoxication in last 30 days, M(SD)

|

1.30 (2.98) | 2.70 (4.71) | .006 |

|

Substance Use (6 month follow-up)†

|

|||

| Number of days of illicit drug use in last 30 days, M(SD) | 2.32 (6.70) | 5.39 (9.95) | <.001 |

| Number of days of alcohol use in last 30 days, M(SD) | 1.14 (3.02) | 2.44 (3.63) | <.001 |

| Number of days of alcohol intoxication in last 30 days, M(SD)

|

1.01 (2.85) | 1.85 (3.09) | .015 |

|

Services Received*

|

|||

| Number of sessions with Behavioral Health Counselor, M(SD) | 1.14 (0.50) | 4.17 (3.49) | <.001 |

| Received only one service session, Percent | 89.35 | 14.89 | <.001 |

Notes.

N=629;

N=553 for whom follow-up data is available. Fischer’s exact test used for categorical variables. Independent samples t test with unequal variance used for continuous variables.

Relationships between substance use and service categories were as expected, with students who would receive BT/RT reporting significantly higher baseline frequency of drug use, alcohol use, and alcohol to intoxication (all ps<.001) than students who would go on to receive BI. There were considerable differences in the number of sessions for each service category. Nearly 90% of adolescents who received BI had just one session with the BHC, whereas approximately 15% of those who received BT/RT had only a single service session.

Because SBIRT inherently bridges the gap between prevention and treatment, SBIRT services were delivered to adolescents determined to be at-risk for substance abuse based on the SDCCHP screening. Not all of these students reported substance use within the past 30 days on the GPRA. Of the youth who were determined to be at risk for substance misuse based on the SDCCHP screening and interaction with the SDCCHP BHCs, 31.8% reported using illicit drugs within the last 30 days, while 42.1% and 36.7% reported consuming alcohol and drinking to intoxication within the last 30 days, respectively. Overall, almost half reported zero baseline days for all three of these variables (47.4%). Of those students who reported illicit drug use in the past 30 days (N=200), 85% reported using only marijuana. Only 8.5% who reported using illicit drugs did not use any marijuana, although, overall, 71% did not use marijuana in the last 30 days.

Change in Substance Use Frequency

Table 2 shows the results of the GEE analyses for days of illicit drug use, days of alcohol use, and days of drinking to intoxication. The Pre-Post Time main effects indicate that adolescents receiving SBIRT services reported significant reductions in drug use from baseline to 6-month follow-up (χ2 (1)=17.57; p<.001). Students also reported significant reductions in days of drinking to intoxication (χ2 (1)=4.92; p<.05), and a non-significant reduction in days of consuming alcohol (χ2 (1)=2.68; p=.10). Examination of estimated likelihoods showed that, from baseline to 6-month follow-up, the predicted counts declined by 36.9% for days of drug use and 22.8% for days of drinking to intoxication. The predicted count for days of alcohol use did not decline significantly.

TABLE 2.

Results of Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) analyses examining differential change for BI vs. BT/RT among adolescents in the NMSBIRT program

| In the last 30 days, number of days of: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Illicit Drug Use | Alcohol Use | Alcohol Intoxication | |

| b(SE) | b(SE) | B(SE) | |

| Female Gender | −0.12 (0.17) | −0.01 (0.15) | −0.02 (0.16) |

| Age (in years) | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.11 (0.07) | 0.19 (0.07)** |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.21 (0.30) | −0.01 (0.27) | 0.15 (0.29) |

| Other/multiple races | −0.43 (0.56) | −1.52 (0.58)** | −1.38 (0.68)* |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | −0.26 (0.23) | −0.29 (0.19) | −0.13 (0.20) |

| Pre-Post Time Effect | −0.43 (0.13)*** | −0.23 (0.12) | −0.22 (0.13) |

| Received BT/RT (ref=BI only) | 0.90 (0.17)*** | 0.71 (0.19)*** | 0.73 (0.19)*** |

| Pre-Post x BT/RT | −0.06 (0.22) | 0.082 (0.23) | −0.08 (0.23) |

| Constant | 1.11 (1.19) | −1.17 (1.06) | −2.62 (1.06)* |

Notes: N=629 (baseline); 553 (follow-up).

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001. The reference category for race is White. Ethnicity is considered a separate variable from race.

Service effects

Service effects were examined to determine whether, relative to baseline substance use frequency, the magnitude of change in substance use was different for adolescents who received BI from those who received BT/RT. While adolescents with higher baseline frequency of substance use were more likely to receive a higher level of intervention (i.e., BT or RT as opposed to BI alone), the nonsignificant Time x Service Level interaction effect indicated that the pattern of change from baseline to follow-up did not differ as a function of services delivered for any of the outcomes (p=.77, .72, and .72 for drug use, alcohol use, and alcohol intoxication, respectively; Table 2).

Additional analyses examined potential effects of frequency of service sessions on changes in substance use from baseline to 6 month follow-up, within each of the BI and BT/RT service categories. Across all of these analyses, nonsignificant interaction effects for Time x Number of Service Sessions revealed that the magnitude of change over time did not vary significantly with number of service sessions for either the BI or the BT/RT subgroups (for the drug use, alcohol, and alcohol intoxication models, respectively, in the BI subgroup: p=.49, .78, and .88; in the BT/RT subgroup: p=.83, .33, and .21).

Service variables controlling for baseline substance use frequency

Analyses were also conducted examining the relationship between service variables and substance use outcomes while controlling for baseline substance use frequency. As expected, the baseline value of the dependent variable was the strongest predictor of 6 month outcomes in all of the models (ps<.001 for all three). Neither service level nor number of sessions were associated with the outcome for either days of illicit drug use or of alcohol intoxication. However, as shown in Table 3, a BT/RT service level was associated with greater number of days of alcohol use at 6 month follow-up (χ2 (1)=6.20; p<.05). When number of service sessions was added to the model, this service level effect was no longer significant (p=.28). Number of service sessions also did not independently predict the 6 month outcome in this model (p=.26).

TABLE 3.

Negative binomial regression predicting days of alcohol use at 6 month follow-up.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| b(SE) | b(SE) | |

| Female Gender | −0.31 (0.20) | −0.28 (0.20) |

| Age (in years) | 0.03 (0.10) | 0.05 (0.10) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.02 (0.47) | 0.00 (0.47) |

| Other/multiple races | −0.11 (0.86) | −.15 (0.86) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | −0.11 (0.30) | −0.11 (0.30) |

| Baseline days of alcohol use | 0.17 (0.04)*** | 0.17 (0.04)*** |

| Received BT/RT (ref=BI only) | 0.66 (0.27)* | 0.38 (0.35) |

| Number of Sessions | 0.08 (0.07) | |

| Constant | −0.61 (1.57) | −0.89 (1.58) |

Notes: N=553 for whom follow-up data is available.

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001. The reference category for race is White. Ethnicity is considered a separate variable from race.

Current User Subsample Analysis

As described above, about half of the at-risk adolescent sample reported not using illicit drugs or alcohol within the last 30 days. Table 4 shows dichotomized (yes/no) tabulations of past 30 day drug use, alcohol use, and drinking to intoxication at baseline and follow-up for the 553 adolescents for whom follow-up data is available. For all three outcomes, the majority of the sample reported no current substance use both at baseline and at follow-up. Based on calculations from Table 4 for the abstainer and current user subsamples, only 7.8% of those who reported no past 30 day illicit drug use at baseline transitioned to use at follow-up, while 45.0% of baseline users were abstainers at follow-up. For alcohol use, 20.3% of those who did not drink at baseline reported drinking at follow-up, but over half (51.1%) of drinkers transitioned to abstinence at follow-up. A similar pattern was evident for drinking to intoxication. Thus, the significant decreases in substance use frequency appear to be largely driven by a substantial proportion of the sample that transitioned from active use to abstinence following the intervention(s).

TABLE 4.

Abstinence vs. current use status at baseline and follow-up.

| ILLICIT DRUG USE | 6-month Follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Abstinent | Current User | ||

| Baseline | Abstinent | 344 (62.2%) | 29 (5.2%) |

|

|

|||

| Current User | 81 (14.7%) | 99 (17.9%) | |

|

| |||

| ALCOHOL USE | 6 month Follow-up | ||

| Abstinent | Current User | ||

| Baseline | Abstinent | 260 (47.0%) | 66 (11.9%) |

|

|

|||

| Current User | 116 (21.0%) | 111 (20.1%) | |

|

| |||

| ALCOHOL TO INTOXICATION | 6-month Follow-up | ||

| Abstinent | Current User | ||

| Baseline | Abstinent | 297 (53.7%) | 61 (11.0%) |

|

|

|||

| Current User | 104 (18.8%) | 91 (16.5%) | |

Note: Current use is defined as any reported use within the last 30 days. Percentages represent the proportion of the total sample that fall in each category.

N=553 cases for whom both baseline and follow-up data are available.

Abstinence refers to past 30 day abstinence, not lifetime abstinence.

GEE analyses were also conducted on subsamples of current users who reported past 30 day substance use at baseline for each of the three outcomes. As expected (due to regression to the mean and the findings of the previous analyses, which included a sizable number of adolescents who were abstinent at baseline), the Time Effect was especially pronounced in these analyses (ps<.001 for all three outcomes). The predicted count for each outcome decreased from baseline to 6-month follow-up by 47.2%, 41.2%, and 46.7% for days of illicit drug use, alcohol use, and alcohol intoxication, respectively.

For all of the outcomes, there was no significant interaction effect between Time Point and receipt of BT/RT, mirroring the findings for the full sample (p=.95, .40, and .63 for illicit drugs, alcohol, and alcohol intoxication, respectively). Similarly, within the BI and BT/RT subgroups, the magnitude of change from baseline to follow-up did not significantly differ as a function of number of service sessions. These findings indicate that, like in the full sample, the effect of Time was not moderated by services received in the subsample that reported past 30 day substance use at baseline.

DISCUSSION

During this project, SBIRT was successfully implemented in 13 schools throughout rural New Mexico, which resulted in nearly 10,000 screenings to identify youth at-risk for substance use. Given the very limited existing literature on adolescent SBIRT, strengths of this study include the relatively large sample size (N=629), the singular focus on adolescents ages 14–17 (which other studies often group with young adults), the large Hispanic population, its multi-site design in natural services settings, the availability of information on service variables, and a fairly robust (87.9%) 6–month follow-up rate.

Students who received an intervention (regardless of intensity level) reported decreases in self-reported days of drinking to intoxication at 6-month follow-up. These results support the findings of the two small clinical trials of BI in school-based settings.7,16 In addition, our sample reported decreases in self-reported drug use at follow-up as compared to baseline. This decrease in drug use over time supports the findings of D’Amico and colleagues15 who, in a random assignment study with 42 participants aged 12–18 seen in a primary care clinic, noted a greater decrease in marijuana use at 3-month follow-up for those who received a BI as compared to usual care. Our findings of change over time can be considered especially robust given that a large proportion of adolescents determined to be at-risk reported no past 30 day substance use at baseline, and remained abstinent at follow-up. Those who reported recent use at baseline had substantial reductions by 6-month follow-up for days of drug use, alcohol use, and drinking to intoxication, although we cannot determine the extent to which these changes can be attributed to regression toward the mean phenomenon. Due to the inconclusive findings from this and other studies, future randomized clinical trials need to investigate whether higher-risk adolescents actually receive greater impact from SBIRT services.

Fully 85% of the study participants who reported illicit drug use reported using solely marijuana in the past 30 days at baseline, and only 8.5% of those students who used illicit drugs did not report using marijuana. Alcohol use and alcohol to intoxication was reported by 42% and 37% of participants at baseline, respectively. The finding that alcohol and marijuana use, as opposed to other illicit drug use, are the predominant problems facing adolescents is consistent with U.S. epidemiologic data4 and has been reported elsewhere.22

The SAMHSA guidelines for the project recommended a higher intensity of intervention (i.e., BT) for those students who reported more problematic alcohol or drug use. Indeed, we found that those with higher self-reported frequency of substance use were more likely to receive BT as compared to BI and were also seen more often by the BHC. The findings with respect to service variables are of some importance, though they must be considered preliminary due to limitations in the study design. The analyses of change found no evidence for differential trajectory of substance use based on service level. Even when controlling for baseline level of use, service variables had little effect on substance use frequency at 6 month follow-up. Service level was associated with outcome only for frequency of alcohol use, with those who received BT/RT reporting more days of drinking at follow-up. One explanation for this finding is that the baseline frequency of drinking is an inadequate indicator of problem severity. On the other hand, it is possible that exposure to greater intensity levels of intervention are not associated with better outcomes beyond those produced by BI. This conclusion, while somewhat counterintuitive, has been reported for adult populations in a recent Cochrane Collaboration review on BIs in medical settings.23 While the limitations of the current study design make these findings tenuous, their implications are considerable if replicated in more rigorous studies with adolescents. They would allow that early, brief interventions can be effective and would permit the provision of services to more students, as compared to providing more intense services to fewer students, without incurring greater personnel costs.

The current study offers several lessons for implementing SBIRT in school settings. Confidentiality poses special challenges in a school-based setting, and the project was designed with this challenge in mind. The BHCs were integrated into existing school-based health centers that were operated by local clinics or health departments. This offered an existing medical infrastructure within which to implement the project that was located within (but was operationally separate from) the schools. Students were informed that BHCs were not school employees and that their records would not be shared with school staff. BHCs also addressed other issues related to psychological well-being and behavioral health. This expansion of their role allowed them to meet a fuller range of needs, and also helped to avoid the perception among students or school staff that the sole focus of BHCs was on substance use. These arrangements allowed the BHCs to assure confidentiality within the normal limits for health care in a school environment. Another lesson for implementation is the importance of staff buy-in. To this end, SDCCHP clinical supervisors made presentations to school staff to orient them to the project, and continued to communicate about challenges and successes throughout the course of the initiative. Different schools bring different assets and challenges, and what works in one school may not translate to another. Thus, it is important to allow flexibility in determining precise operational procedures without compromising project objectives.

There are several limitations to the present study, many of which are rooted in the inherent limitations of retrospective analysis of administrative data for large projects. Only a limited number of common measures were available for all intervention recipients, and participants’ alcohol and drug use was based on self-report only. While this is an accepted research method in this population,24 its reliability has varied in studies in which comparisons were made with objective measures25 or in repeated surveying during longitudinal research.26 Although the project was designed to mitigate confidentiality concerns, it is possible that such concerns impacted both the accuracy of self-report and willingness to utilize services. The present report used a pre-post design in which the students served as their own controls. In the absence of a no-treatment control group it is not possible to rule out changes in alcohol or drug use related to maturation or social desirability impacting self-report. Additionally, we cannot rule out natural fluctuations due to regression to the mean. This is a concern for comparisons of BI and BT/RT on change in frequency of use as well, since those receiving higher intensity services presumably were at higher risk for substance misuse. However, service variables had little effect on frequency of illicit drug use or alcohol intoxication at 6 months when controlling for baseline level of use, although differences based on services received were observed for frequency of drinking. Data are not available on utilization of services outside of the school-based SBIRT program, although participation in such services could potentially impact outcomes. While the analysis sample was very similar to the larger number of adolescents served through the SBIRT initiative on most measures, it included a higher proportion of females and thus may not be perfectly representative. This could be due to short interruptions in evaluation that are unavoidable in large-scale projects in which the primary focus is service delivery rather than data collection. Finally, while the large Hispanic population and inclusion of non-urban locations strengthens the study, it is not known how well these findings would generalize to other population groups or areas of the country.

Despite these limitations, the current study provides a rare look at SBIRT services for adolescents as delivered in real-world, rural school-based settings in a southwestern state. Although school-based SBIRT appears to be a promising approach to preventing, identifying and treating students at risk for alcohol and drug problems, more rigorous research is needed to establish its efficacy and to make evidence-driven determinations with regard to service structure. The current study implies several directions for future research. Future research should establish definitively the effectiveness of school-based SBIRT using randomized trials. It will also be important to determine the cost-effectiveness of providing such services, particularly in comparison to lengthier preventive interventions commonly delivered in school settings. Finally, future research should examine different implementation models for school-based SBIRT and optimize the service mix offered based on the experimental and naturalistic evidence.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by Grant TI 15958 from the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, (SAMHSA), Bethesda, MD (Dr. Gonzales) and grant R01 DA026003 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, MD (Dr. Schwartz).

We wish to thank Melissa Morsell Irwin and Beth Ruppert for their assistance with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest:

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Marsden J, Stillwell G, Barlow H, et al. An evaluation of a brief motivational intervention among young ecstasy and cocaine users: no effect on substance and alcohol use outcomes. Addiction. 2006;101:1014–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCambridge J, Strang J. The efficacy of single-session motivational interviewing in reducing drug consumption and perceptions of drug-related risk and harm among young people: results from a multi-site cluster randomized trial. Addiction. 2004;99:39–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Analysis. Vol. 1. Vienna: UNODC; 2005. World Drug Report. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. NSDUH Series H-39, HHS Publication No SMA 10–4609. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; 2010. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncan S, Salter A, Duncan T, Hops H. Adolescent alcohol use development and young adult outcome. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;49:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CY, O’Brien MS, Anthony JC. Who becomes cannabis dependent after onset of use? Epidemiological evidence from the United States: 2000–2001. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winters KC, Leitten W, Wagner E, Tevyaw TL. Use of brief intervention for drug abusing teenagers within a middle and high school setting. Journal of School Health. 2007;77:196–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breslin C, Li S, Sdao-Jarvie K, Tupker E, Ittig-Deland V. Brief Treatment for Young Substance Abusers: A Pilot Study in an Addiction Treatment Setting. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight JR, Sherrit L, Shrier LA. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:607–614. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knight JR, Harris SK, Sherritt L, et al. Prevalence of positive substance abuse screen results among adolescent primary care patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:1035–1041. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.11.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spirito A, Monti PM, Barnett NP, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department. J Pediatr. 2004;145:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:527–535. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maio RF, Shope JT, Blow FC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an emergency department-based interactive computer program to prevent alcohol misuse among injured adolescents. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boekeloo BO, Jerry J, Lee-Ougo WI, et al. Randomized trial of brief office-based interventions to reduce adolescent alcohol use. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:635–642. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.7.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Amico E, Miles JN, Stern S, Meredity LSBMIfTaRoSUCARPSiaPCC. Brief Motivational Interviewing for Teens at Risk of Substance Use Consequences: A Randomized Pilot Study in a Primary Care Clinic. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grenard JL, Ames SL, Wiers RW, Thush C, Stacy AW, Sussman S. Brief intervention for substance use among at-risk adolescents: a pilot study. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:188–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winters KC, Leitten W. Brief intervention for drug-abusing adolescents in a school setting. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:249–254. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madras BK, Compton WM, Avula D, Stegbauer T, Stein JB, Clark HW. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:280–295. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, Farrell M, Vander Bilt J, Shaffer HJ. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:591–596. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godley SH, Meyers RJ, Smith JE, et al. The Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (ACRA) for adolescent cannabis users. Vol. 4. Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deas D. Evidence-based Treatment for alcohol use disorders. Pediatrics. 2010;121(s4):s348–s354. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaner EFS, Dickinson HO, Beyer F, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007. 2007;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2003. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53(SS-2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams RJ, Nowarzki N. Validity of adolescent self-report of substance use. Substance Use & Misue. 2005;40:299–311. doi: 10.1081/ja-200049327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Percy A, McAlister S, Higgins K, McCrystal P, Thornton M. Response consistency in young adolescents’ drug use self-reports: a recanting rate analysis. Addiction. 2005;100:189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]