Abstract

Zebrafish have become a popular organism for the study of vertebrate gene function1,2. The virtually transparent embryos of this species, and the ability to accelerate genetic studies by gene knockdown or overexpression, have led to the widespread use of zebrafish in the detailed investigation of vertebrate gene function and increasingly, the study of human genetic disease3–5. However, for effective modelling of human genetic disease it is important to understand the extent to which zebrafish genes and gene structures are related to orthologous human genes. To examine this, we generated a high-quality sequence assembly of the zebrafish genome, made up of an overlapping set of completely sequenced large-insert clones that were ordered and oriented using a high-resolution high-density meiotic map. Detailed automatic and manual annotation provides evidence of more than 26,000 protein-coding genes6, the largest gene set of any vertebrate so far sequenced. Comparison to the human reference genome shows that approximately 70% of human genes have at least one obvious zebrafish orthologue. In addition, the high quality of this genome assembly provides a clearer understanding of key genomic features such as a unique repeat content, a scarcity of pseudogenes, an enrichment of zebrafish-specific genes on chromosome 4 and chromosomal regions that influence sex determination.

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) was first identified as a genetically tractable organism in the 1980s. The systematic application of genetic screens led to the phenotypic characterization of a large collection of mutations1,2. These mutations, when driven to homozygosity, can produce defects in a variety of organ systems with pathologies similar to human disease. Such investigations have also contributed notably to our understanding of basic vertebrate biology and vertebrate development. In addition to enabling the systematic definition of a large range of early developmental phenotypes, screens in zebrafish have contributed more generally to our understanding of the factors controlling the specification of cell types, organ systems and body axes of vertebrates7–9.

Although its contributions have already been substantial, zebrafish research holds further promise to enhance our understanding of the detailed roles of specific genes in human diseases, both rare and common. Increasingly, zebrafish experiments are included in studies of human genetic disease, often providing independent verification of the activity of a gene implicated in a human disease3,5,10. Essential to this enterprise is a high-quality genome sequence and complete annotation of zebrafish protein-coding genes with identification of their human orthologues.

The zebrafish genome-sequencing project was initiated at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in 2001. We chose Tübingen as the zebrafish reference strain as it had been used extensively to identify mutations affecting embryogenesis2. Our strategy resembled the clone-by-clone sequencing approach adopted previously for both the human and mouse genome projects. The Zv9 assembly is a hybrid of high-quality finished clone sequence (83%) and whole-genome shotgun(WGS) sequence (17%), with a total size of 1.412 gigabases (Gb) (Table 1). The clone and WGS sequence is tied to a high-resolution, high-densitymeiotic map called the Sanger AB Tübingen map (SATmap), named after the strains of zebrafish used to make the map (Supplementary Information).

Table 1.

Assembly and annotation statistics for the Zv9 assembly

| Assembly | Annotation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total length (bp) | 1,412,464,843 | Protein-coding genes | 26,206 |

| Total clone length (bp) | 1,175,673,296 | Pseudogenes | 218 |

| Total WGS31 contig length (bp) | 234,099,447 | RNA genes | 4,556 |

| Placed scaffold length (bp) | 1,357,051,643 | Immunoglobulin/T-cell receptor gene segments | 56 |

| Unplaced scaffold length (bp) | 55,413,200 | Total transcripts | 53,734 |

| Maximum scaffold length (bp) | 12,372,269 | Total exons | 323,599 |

| Scaffold N50 (bp) | 1,551,602 | - | - |

| No. of clones | 11,100 | - | - |

| No of WGS31 contigs | 26,199 | - | - |

| No. of placed scaffolds | 3,452 | - | - |

| No. of unplaced scaffolds | 1,107 | - | - |

Data are based on Ensembl version 67. N50, the scaffold size above which 50% of the total length of the sequence assembly can be found.

Zebrafish are members of the teleostei infraclass, a monophyletic group that is thought to have arisen approximately 340 million years ago from a common ancestor11. Compared to other vertebrate species, this ancestor underwent an additional round of whole-genome duplication (WGD) called the teleost-specific genome duplication (TSD)12. Gene duplicates that result from this process are called ohnologues (after Susumu Ohno who suggested this mechanism of gene duplication)13. Zebrafish possess 26,206 protein-coding genes6, more than any previously sequenced vertebrate, and they have a higher number of species-specific genes in their genome than do human, mouse or chicken. Some of this increased gene number is likely to be a consequence of the TSD.

A direct comparison of the zebrafish and human protein-coding genes reveals a number of interesting features. First, 71.4% of human genes have at least one zebrafish orthologue, as defined by Ensembl Compara14 (Table 2). Reciprocally, 69% of zebrafish genes have at least one human orthologue. Among the orthologous genes, 47% of human genes have a one-to-one relationship with a zebrafish orthologue. The second largest orthology class contains human genes that are associated with many zebrafish genes (the ‘one-human-to-many-zebrafish’ class), with an average of 2.28 zebrafish genes for each human gene, and this probably reflects the TSD. A few notable human genes have no clearly identifiable zebrafish orthologue; for example, the leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF), oncostatin M (OSM) or interleukin-6 (IL6) genes, although the receptors lifra, lifrb, osmr and il6r are clearly present in the zebrafish genome. It is possible that zebrafish proteins with functionally similar activities to LIF, OSM and IL-6 exist, but that their sequence divergence is so great that they cannot be recognized as orthologues. Similarly, the zebrafish genome has no BRCA1 orthologue, but does have an orthologue of the BRCA1-associated BARD1 gene, which encodes an associated and functionally similar protein and a brca2 gene, which plays an important role in oocyte development, probably reflecting its role in DNA damage repair15.

Table 2.

Comparison of human and zebrafish protein-coding genes and their orthology relationships

| Relationship type | Human | Core relationship | Zebrafish | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One to one | - | 9,528 | - | - |

| One to many | 3,105 | - | 7,078 | 1:2.28 |

| Many to one | 1,247 | - | 489 | 2.55:1 |

| Many to many | 743 | 233 | 934 | 1:1.26 |

| Orthologous total | 14,623 | 13,355 | 18,029 | 1:1.28 |

| Unique | 5,856 | - | 8,177 | - |

| Coding-gene total | 20,479 | - | 26,206 | - |

Data and orthology relationship definitions are based on Ensembl Compara version 67 (http://www.ensembl.org/info/docs/compara/homology_method.html).

Zebrafish have been used successfully to understand the biological activity of genes orthologous to human disease-related genes in greater detail3–5. To investigate the number of potential disease-related genes, we compared the list of human genes possessing at least one zebrafish orthologue with the 3,176 genes bearing morbidity descriptions that are listed in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database. Of these morbid genes, 2,601 (82%) can be related to at least one zebrafish orthologue. A similar comparison identified at least one zebrafish orthologue for 3,075 (76%) of the 4,023 human genes implicated in genome wide association studies (GWAS).

Zv9 shows an overall repeat content of 52.2%, the highest reported so far in a vertebrate. All other sequenced teleost fish exhibit a much lower repeat content, with an average of less than 30%. This result suggests that the evolutionary path leading to the zebrafish experienced an expansion of repeats, possibly facilitated by a population bottleneck. Alternatively, the repeat content of the other sequenced teleost species may be under-represented, as these assemblies are mostly WGS16.

The majority of transposable elements found in the human genome are type I (retrotransposable elements), with more than 4.3 million placements covering 44% of the sequence, whereas only 11% of the zebrafish genome sequence is covered by type I elements in less than 500,000 instances. In contrast, the zebrafish genome contains a marked excess of type II DNA transposable elements. Indeed, 2.3 million instances of type II DNA transposable elements cover 39% of the zebrafish genome sequence (Supplementary Table 12), whereas type II repeats cover only 3.2% of the human genome.

This pronounced abundance of type II transposable elements is unique among the sequenced vertebrate genomes, and the genome sequence shows evidence of recently active type II transposable elements. The closest vertebrate species in terms of the abundance of type II transposable elements is Xenopus tropicalis (25% type II transposable elements), whereas the sequenced and annotated teleost fish (the pufferfish Takifugu and Tetraodon, the three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) and the medaka (Oryzias latipes)) each possess type II transposable element coverage of less than 10%, which may relate to the fact that the zebrafish genome diverges basally from the other sequenced and annotated teleost genomes17. Zebrafish type II transposable elements are divided into 14 superfamilies with 401 repeat families in total (Supplementary Table 12). The DNA and hAT superfamilies are the most abundant and diverse in the zebrafish genome, together covering 28% of the sequence. The type II transposable element abundance of zebrafish, or lack of retrotransposable elements, may provide an explanation for the low zebrafish pseudogene content (Supplementary Table 14).

The long arm of chromosome 4 is unique among zebrafish genomic regions, owing to its relative lack of protein-coding genes and its extensive heterochromatin. Chromosome 4 is known to be late-replicating and hybridization studies suggest that genomic copies of 5S ribosomal DNA (rDNA), which are not notably present on any other chromosome, are scattered along the long arm at high redundancy18. Immediately after the presumed centromere at approximately 24 megabases (Mb), the sequence landscape (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. A4) shows a remarkable increase in repeat content, which continues through to the telomere of the long arm. At approximately 27 Mb, the otherwise uniform presence of the satellite repeat SAT-2 on the long arm ends abruptly. This location is also the starting point of uniform MOSAT-2 distribution, a satellite repeat that is nearly absent from all other chromosomes but highly enriched on the long arm of chromosome 4. The subtelomeric region of the long arm shows a distinct distribution of repeat elements, with relatively fewer interspersed elements and an increased content of satellite, simple and tandem repeats that do not harbour 5S rDNA sequences. Moreover, the gene content is reduced on the long arm and the guanine–cytosine content is slightly increased.

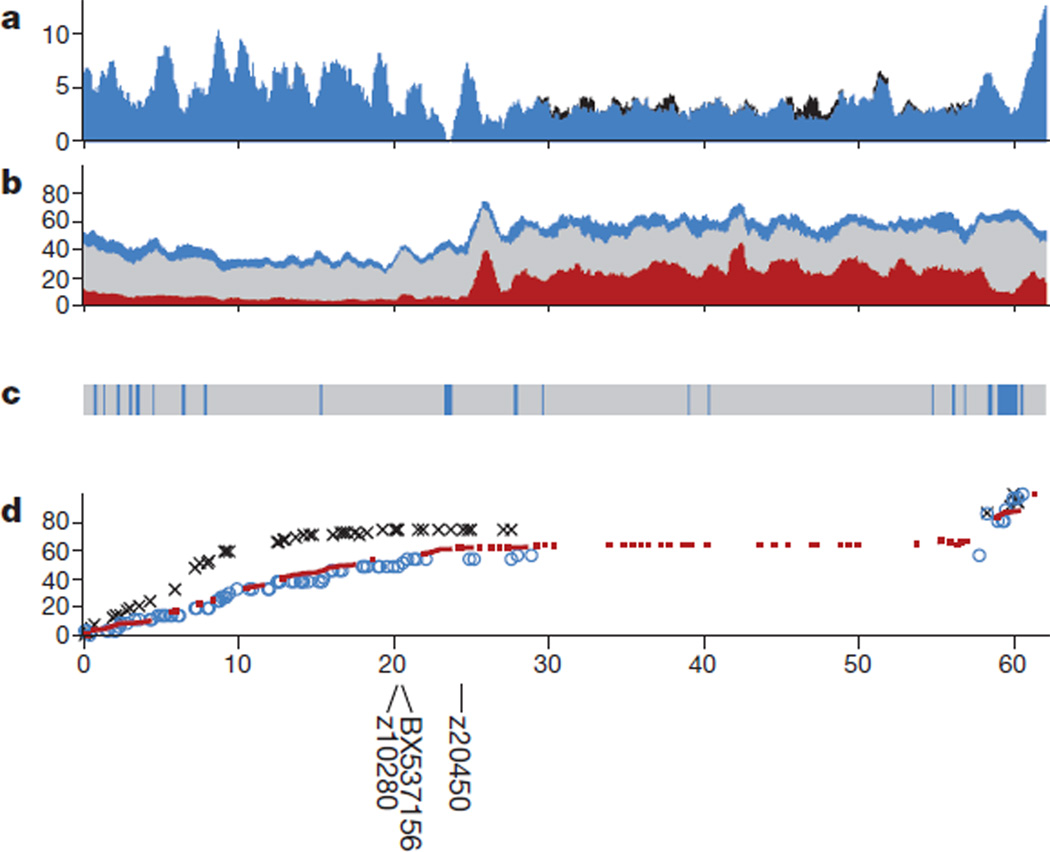

Figure 1. Landscape of chromosome 4.

a, Exon coverage (blue), stacked with coverage by snRNA exons (black). b, Stacked repeat coverage, divided into type I transposable elements (red), type II transposable elements (grey) and other repeat types (blue), including dust, tandem and satellite repeats. c, Sequence composition (grey bars, clones; blue bars, WGS contigs). d, Genetic marker placements (red, SATmap markers; blue, heat shock meiotic map markers; black, Massachusetts General Hospital meiotic map markers). Marker placements have been normalized so that the maps can be compared. Near-centromeric clones are positioned at 20Mb (BX537156), 20.2Mb (Z10280) and 24.4Mb (Z20450)28. The x axis shows the chromosomal position in Mb. a and b were calculated as percentage coverage over 1-Mb overlapping windows (y axis), with a 100-kb shift between each window. c and d were calculated over 100-kb windows. The y axis for d shows the normalization of marker positions relative to the span of the individual map. Similar graphs for the other chromosome are provided in the Supplementary Information.

The long arm of chromosome 4 also has a special structure with respect to gene orthology and synteny. Approximately 80% of the genes present have no identifiable orthologues in human. In fact, 110 genes (out of 663) have no identifiable orthologues in any other sequenced teleost genome and indeed seem to be zebrafish-specific genes. The genes in this region are highly duplicated, with 31 ancestral gene families alone providing 77.5% of the genes, the largest of which contains no less than 109 duplicates in this region. The largest of these families correspond to NOD-like receptor proteins19 with putative roles in innate immunity and zinc finger proteins. We also observed a very high density of small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) on chromosome 4, and in particular those that encode spliceosome components. The cohort of snRNAs carried on the long arm of chromosome 4 accounts for 53.2% of all snRNAs in the zebrafish genome. In addition, in a specific group of zebrafish derived recently from a natural population, the subtelomeric region of the long arm of chromosome 4 has been found to contain a major sex determinant with alleles that are 100% predictive of male development and 85% predictive of female development, suggesting that this chromosome may be, might have been, or may be becoming, a sex chromosome in this particular population20.

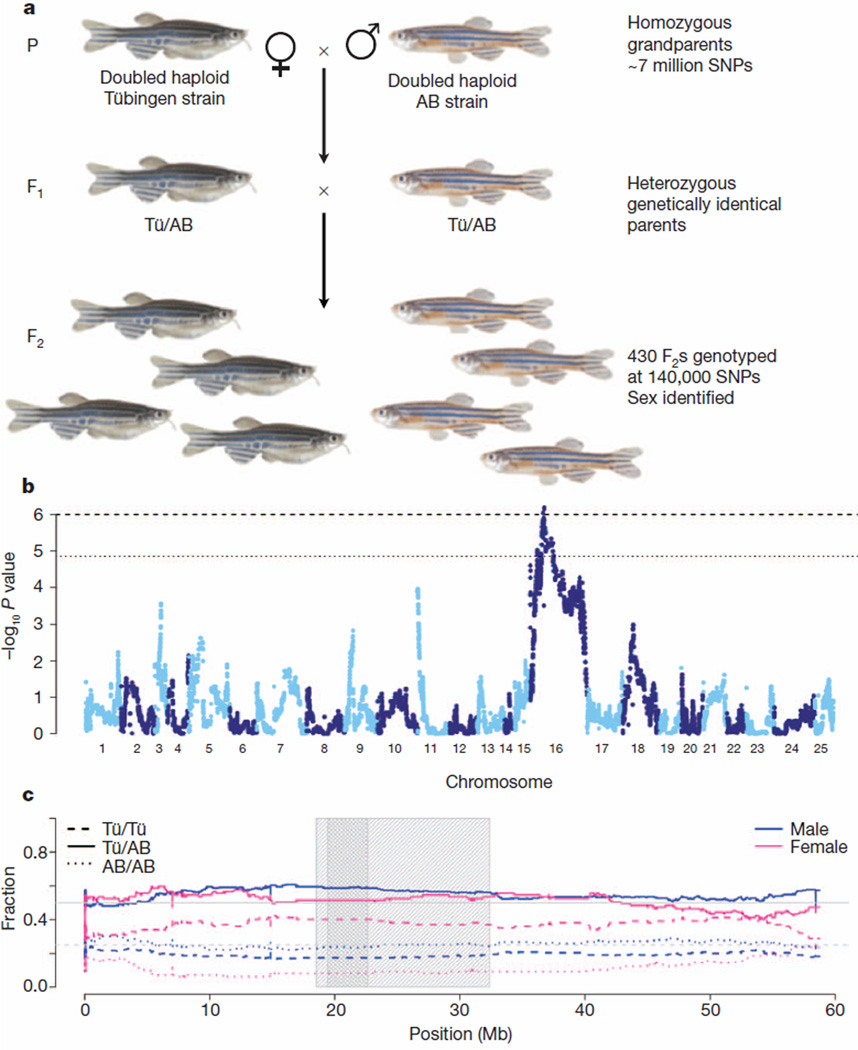

In addition to the chromosome 4 sex determinant, three other separate genomic regions have been identified as influencing sex determination, and these vary between the strains and even within the families studied20,21. Our meiotic map, SATmap, which was generated to anchor the genomic sequence, provided an opportunity to examine whether there are any strong signals for sex determination. To generate SATmap we took advantage of the fact that it is possible to create double haploid individuals that contain only maternally derived DNA, that are homozygous at every locus and that can be raised until they are fertile22 (Fig. 2a). To investigate the interesting finding that SATmap F1 fish could be either male or female while being genetically identical and heterozygous at every polymorphic locus, we sought a genetic signal for sex determination in the F2 generation, in which these polymorphisms segregate. Using morphological secondary sexual traits, we were able to score the sex of 332 genotyped F2 individuals. Although most chromosomes showed no significant genetic bias for a particular sex, we found that most of chromosome 16 carried a strong signal (P = 9.1 × 10−7) with a broad peak around the centromere (Fig. 2b, c). Homozygotes for the Tübingen (grandmaternal) allele had a very high probability of being female, whereas homozygotes for the AB (grandpaternal) allele were very unlikely to be female (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Sex determination signal on chromosome 16.

a, Breeding scheme for SATmap. Double haploid generation zero (G0) founders were sequenced to approximately 40× depth using Illumina GAII technology. We found approximately 7 million SNPs between the two SATmap founders. This number of SNPs between just two homozygous zebrafish individuals is far in excess of that seen between any two humans and is nearly one-fifth of all SNPs measured among 1,092 human diploid genomes29. Genetically identical, heterozygous F1 fish of both sexes resulted from crossing the founders. The F1 individuals were crossed to generate a panel of F2 individuals, each with its own unique set of meiotic recombinations between AB and Tübingen (Tü) chromosomes, which were uncovered by dense genotyping with a set of 140,306 SNPs covering most of the genome. b, Genome-wide P values for tests of genotype difference between sexes, arranged by chromosome. The dotted line corresponds to differences that are expected once in 100 random genome scans, and the dashed line corresponds to differences expected once in 1,000 random genome scans. The only locus that is statistically significant at these levels is on chromosome 16. c, Genotype frequencies for males and females on chromosome 16. The grey line at 0.5 corresponds to expectation for heterozygotes (solid lines) and the grey line at 0.25 corresponds to expectation for homozygotes (dashed and dotted lines). The light grey shaded box corresponds to the region in which empirical P < 0.01, the dark grey shaded box corresponds to the region in which P < 0.001.

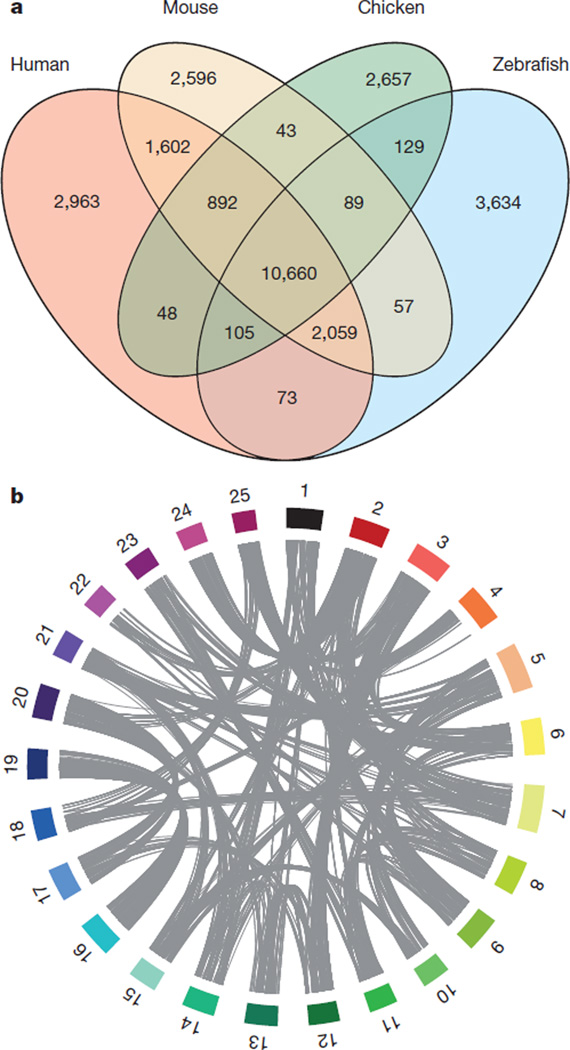

The number of protein-coding genes among vertebrates is relatively stable, although even closely related species may show great disparities in the nature of their protein-coding gene content. We carried out a four-way comparison between the proteome of two mammals (human and mouse), a bird (chicken) and the zebrafish to quantify the fraction of shared and species-specific genes present in each genome (Fig. 3a). A core group of 10,660 genes is found in all four species and probably approximates an essential set of vertebrate protein-coding genes. This number is somewhat less than the core set of 11,809 vertebrate genes identified previously as being common to three fish genomes (Tetraodon, medaka, zebrafish) and three amniotes (human, mouse, chicken)16, but the discrepancy probably reflects the improved annotation of these genomes that often results in fusing fragmented gene structures. Each taxon has between 2,596 and 3,634 species-specific genes. The notable excess observed in zebrafish may be a consequence of the WGD, because pairs of duplicated genes that arose from the WGD, but with no orthologue in amniotes, are counted as two specific genes. Furthermore, 2,059 genes are found in human, mouse and zebrafish but not in chicken, and this number is two times higher than the number of genes that are found in all amniotes but not in zebrafish (892). It is unclear whether these genes have been lost along the evolutionary branch leading to the chicken, or whether this is due to annotation or orthology assignation errors in the chicken genome.

Figure 3. Evolutionary aspects of the zebrafish genome.

a, Orthologue genes shared between the zebrafish, human, mouse and chicken genomes, using orthology relationships from Ensembl Compara 63. Genes shared across species are considered in terms of copies at the time of the split. For example, a gene that exists in one copy in zebrafish but has been duplicated in the human lineage will be counted as only one shared gene in the overlap. b, The ohnology relationships between zebrafish chromosomes. Chromosomes are represented as coloured blocks. The position of ohnologous genes between chromosomes are linked in grey (for clarity, links between chromosomes that share less than 20 ohnologues have been omitted). The image was produced using Circos30.

We identified double-conserved synteny (DCS) blocks between all sequenced tetrapods and four fish genomes (zebrafish, medaka, stickleback and Tetraodon). DCS blocks are defined as runs of genes in the non-duplicated species that are found on two different chromosomes in the species that underwent aWGD23, although the genes may not be adjacent in the duplicated species24. The DCS between zebrafish and human are represented on either side of each human chromosome (Supplementary Fig. 15). Using DCS blocks, we identified zebrafish paralogous genes that are part of DCS blocks and consistent with the locally alternating chromosomes, hence with an origin at the TSD. We identified 3,440 pairs of such ohnologues (26% of the all genes), for a total of 8,083 genes when subsequent duplications are taken into account. It is notable that although true pairs of ohnologues may exist within the same chromosome owing to post-TSD rearrangements, we excluded such cases as we cannot reliably distinguish them from segmental duplications. This number of ancestral genes retained as duplicates in zebrafish is higher, both in absolute number and in proportion, than in other fish genomes (chi-squared test, all P<3 × 10−5).

We compared the 8,083 zebrafish TSD ohnologues with human ohnologues originating from the two rounds of WGD that are common to all vertebrates and find that the two sets overlap strongly (chi-squared test, P <2 × 10−16). In general, zebrafish ohnologous pairs are enriched in specific functions (neural activity, transcription factors) and are orthologous to mammalian genes under stronger evolutionary constraint than genes that have lost their second copy.

A circular representation of ohnologue pairs (Fig. 3b) highlights chromosomes, or parts of chromosomes, that descended from the same pre-duplication ancestral chromosome (for example, chromosomes 3 and 12, 17 and 20, 16 and 19).Among zebrafish chromosomes, chromosome 16 and chromosome 19 are unique in their one-to-one conservation of synteny. Consistent with the conservation of synteny, chromosome 16 and chromosome 19 possess clusters of orthologues of genes associated with the mammalian major histocompatibility complex (MHC) as well as the hoxab and hoxaa clusters, respectively, which are each orthologous to the human HOXA cluster25.

Since the earliest whole-genome shotgun-only assembly became public in 2002, the zebrafish reference genome sequence has enabled many new discoveries to be made, in particular the positional cloning of hundreds of genes from mutations affecting embryogenesis, behaviour, physiology, and health and disease. Moreover, the annotated reference genome has enabled the generation of accurate whole-exome enrichment reagents, which are accelerating both positional cloning projects and new genome-wide mutation discovery efforts26,27.Although the zebrafish reference genome sequencing is complete, a few poorly assembled regions remain, which are being resolved by the Genome Reference Consortium (http://genomereference.org).

METHODS SUMMARY

We generated cloned libraries of large fragments of genomic DNA, assembled a physical map of large-insert clones and completely sequenced a set of minimally overlapping clones. In addition, we generated WGS sequences by end-sequencing a mixture of large- and short-insert libraries. Overlapping clone sequences were combined with WGS sequences and tied to the meiotic map, SATmap, which enabled independent placement and orientation of clones in the genome sequence. The sequence data can be found in the BioProject database, under accession number PRJNA11776.

To obtain evidence for a more complete description of protein-coding genes, we used high-throughput short-read complementary DNA sequencing and obtained a deep-coverage data set for messenger RNAs expressed in zebrafish at various stages of development and in adult tissues6. Finally, a standard Ensembl gene build, incorporating filtered elements from the complementary DNA sequencing gene build, was merged with the manually curated gene models to produce a comprehensive annotation in Ensembl version 67 (http://may2012.archive.ensembl.org/Danio_rerio/Info/Index). Detailed descriptions of all the methods used for this project are available in the Supplementary Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank R. Durbin, E. Birney, A. Scally, C. P. Ponting, E. Busch-Nentwich and R. Kettleborough for helpful discussions, as well as F. L. Marlow and P. Aanstad for critical reading and helpful comments on manuscripts. We thank the zebrafish information network (ZFIN) for funding part of the manual annotation of the zebrafish genome and the ZFIN staff for support with gene nomenclature and other genome issues. We also thank the Genome Reference Consortium for the maintenance and improvement of the zebrafish genome assembly. We are indebted to the Ensembl team for providing a browser and database that greatly facilitated the use and the analyses of the zebrafish genome. We thank A. Pirani at Affymetrix for genotyping advice support, and the Zebrafish International Resource Center (ZIRC) for distributing the SAT strain. J.H.P. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grantR01 GM085318 (to J.H.P.), NIH grant P01 HD22486 (to J.H.P.) and R01 OD011116 (later changed to R01 RR020833) (to J.H.P.). We would like to acknowledge the support of the European Commission’s Sixth Framework Programme (contract no. LSHG-CT-2003-503496, ZF-MODELS) and Seventh Framework Programme (grant no. HEALTH-F4-2010-242048, ZF-HEALTH). R.G. was supported by the German Human Genome Project (DHGP Grant 01 KW 9627 and 01 KW 9919). C.N.-V., G.-J.R. and R.G. were supported by the NIH (NIH grant 1 R01 DK55377-01A1). The Zebrafish Genome Project at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute was funded by Wellcome Trust grant number 098051.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

Author Contributions K.H., M.D.C., D.L.S., C.B., H.R.C., A.E. and K.M. wrote the manuscript and Supplementary Information. M.D.C., C.F.T., I.S., J.C.B., A.R.,S.W. andC.L. produced the SATmap. Z.N. and Y.G. produced the WGS31 assembly. J.T., W.C. and C.F.T. generated the Zv9 assembly. Previous assemblies were produced by M.C., who developed the first assembly integration process, and by S.R., T.E. and I.S. coordinated by K.H. The analyses and figures for the manuscript were produced by J.T., K.H., C.B., M.M., J.H., L.T.Q., J.A.G.-A. and J.Y. K.A., J.W., S.P., J.C., G.T., G.H., G.G., P.H. and B.K. are involved in the ongoing improvement of the zebrafish genome assembly. Manual annotation was produced by G.K.L., D.L., E.K., S.D., H.S., J.A.-K. and J.L. and coordinated by J.H. and M.W. Automated annotation (Ensembl) was provided by J.E.C., S.W., J.-H.V., S.T. and S.M.J.S. The genome sequencing was carried out by C.C., K.M., S.M., C.S., J.C., B.F., E.L., S.F.M., M.J., M.Q., D.W., A.H., J.B., S.S., K.M., B.P., J..D., C.C., K.O., B.M., G.K., B.P., A.T., N.C., C.J., S.C., M.S., R.G., P.H., N.B., C.S., J.H., K.H., G.P., J.L., H.B., C.H., D.G., D.W., C.R., L.D., K.L., L.R., K.A., D.L., S.M., R.G., C.G., D.M., S.N., G.B., S.W., M.K., J.B., C.M., E.G., M.H., N.S., D.B., D.S., J.W., A.B., S.H., K.O., M.M.-M., L.B., S.M., P.W., A.E., N.M.,M.E., R.W., G.C., J.C., A.T., D.G., C.S., R.P., R.A., E.H., A.K., J.G., N.F., R.H., P.G., D.K., C.B. and S.P. The generation of maps used in the initial assemblies and the production of clone tiling paths were carried out by R.K., S.H.,G.-J.R., Y.Z., C.R.,R.C.,D.E.,D.W., L.M.,M.D., I.G., A.B., C.M.D., Z.E.-Ü., C.E.,H.G., M.G., L.K., A.K., J.K., M.K.,M.O., S.R.-G., M.T.,R.B., F.Y., N.P.C., R.G., R.H.A.P. and C.L. K.O., B.Z. and P.J.d.J. generated and provided clone libraries. The Zebrafish Genome Project was coordinated by L.I.Z., J.H.P., C.N.-V., T.J.P.H., J.R. and D.L.S.

Author Information Sequence data have been submitted to the BioProject database under accession PRJNA11776.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Driever W, et al. A genetic screen for mutations affecting embryogenesis in zebrafish. Development. 1996;123:37–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haffter P, et al. The identification of genes with unique and essential functions in the development of the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Development. 1996;123:1–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golzio C, et al. KCTD13 is a major driver of mirrored neuroanatomical phenotypes of the 16p11.2 copy number variant. Nature. 2012;485:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature11091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panizzi JR, et al. CCDC103 mutations cause primary ciliary dyskinesia by disrupting assembly of ciliary dynein arms. Nature Genet. 2012;44:714–719. doi: 10.1038/ng.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roscioli T, et al. Mutations in ISPD cause Walker-Warburg syndrome and defective glycosylation of alpha-dystroglycan. Nature Genet. 2012;44:581–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins JE, White S, Searle SM, Stemple DL. Incorporating RNA-seq data into the zebrafish Ensembl genebuild. Genome Res. 2012;22:2067–2078. doi: 10.1101/gr.137901.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talbot WS, et al. A homeobox gene essential for zebrafish notochord development. Nature. 1995;378:150–157. doi: 10.1038/378150a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gritsman K, et al. The EGF-CFC protein one-eyed pinhead is essential for nodal signaling. Cell. 1999;97:121–132. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80720-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ober EA, Verkade H, Field HA, Stainier DY. Mesodermal Wnt2b signalling positively regulates liver specification. Nature. 2006;442:688–691. doi: 10.1038/nature04888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tobin DM, et al. Host genotype-specific therapies can optimize the inflammatory response to mycobacterial infections. Cell. 2012;148:434–446. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amores A, Catchen J, Ferrara A, Fontenot Q, Postlethwait JH. Genome evolution and meiotic maps by massively parallel DNA sequencing: spotted gar, an outgroup for the teleost genome duplication. Genetics. 2011;188:799–808. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.127324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer A, Schartl M. Gene and genome duplications in vertebrates: the one-to-four (-to-eight in fish) rule and the evolution of novel gene functions. Curr.Opin. Cell Biol. 1999;11:699–704. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe K. Robustness–it’s not where you think it is. Nature Genet. 2000;25:3–4. doi: 10.1038/75560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vilella AJ, et al. EnsemblCompara GeneTrees: complete, duplication-aware phylogenetic trees in vertebrates. Genome Res. 2009;19:327–335. doi: 10.1101/gr.073585.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodríguez-Mari A, et al. Roles of brca2 (fancd1) in oocyte nuclear architecture, gametogenesis, gonad tumors, and genome stability in zebrafish. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasahara M, et al. The medaka draft genome and insights into vertebrate genome evolution. Nature. 2007;447:714–719. doi: 10.1038/nature05846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Postlethwait JH. The zebrafish genome in context: ohnologs gone missing. J. Exp. Zool. B. 2007;308:563–577. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sola L, Gornung E. Classical and molecular cytogenetics of the zebrafish, Danio rerio (Cyprinidae, Cypriniformes): an overview. Genetica. 2001;111:397–412. doi: 10.1023/a:1013776323077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stein C, Caccamo M, Laird G, Leptin M. Conservation and divergence of gene families encoding components of innate immune response systems in zebrafish. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R251. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson JL, et al. Multiple sex-associated regions and a putative sex chromosome in zebrafish revealed by RAD mapping and population genomics. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley KM, et al. An SNP-based linkage map for zebrafish reveals sex determination loci. G3 (Bethesda) 2011;1:3–9. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Streisinger G, Walker C, Dower N, Knauber D, Singer F. Production of clones of homozygous diploid zebra fish (Brachydanio rerio) Nature. 1981;291:293–296. doi: 10.1038/291293a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellis M, Birren BW, Lander ES. Proof and evolutionary analysis of ancient genome duplication in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2004;428:617–624. doi: 10.1038/nature02424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaillon O, et al. Genome duplication in the teleost fish Tetraodon nigroviridis reveals the early vertebrate proto-karyotype. Nature. 2004;431:946–957. doi: 10.1038/nature03025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amores A, et al. Developmental roles of pufferfish Hox clusters and genome evolution in ray-fin fish. Genome Res. 2004;14:1–10. doi: 10.1101/gr.1717804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kettleborough RNW, et al. A systematic genome-wide analysis of zebrafish protein-coding gene function. Nature. doi: 10.1038/nature11992. (in the press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varshney GK, et al. A large-scale zebrafish gene knockout resource for the genome-wide study of gene function. Genome Res. 2013;23:727–735. doi: 10.1101/gr.151464.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freeman JL, et al. Definition of the zebrafish genome using flow cytometry and cytogenetic mapping. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:195. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krzywinski M, et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.