Abstract

We previously reconstituted Z rings in tubular multilamellar liposomes with FtsZ-YFP-mts, where mts is a membrane-targeting amphiphilic helix. These reconstituted Z rings generated a constriction force but did not divide the thick-walled liposomes. Here we developed a unique system to observe Z rings in unilamellar liposomes. FtsZ-YFP-mts incorporated inside large, unilamellar liposomes formed patches that produced concave distortions when viewed at the equator of the liposome. When viewed en face at the top of the liposome, many of the patches were seen to be small Z rings, which still maintained the concave depressions. We also succeeded in reconstituting the more natural, two-protein system, with FtsA and FtsZ-YFP (having the FtsA-binding peptide instead of the mts). Unilamellar liposomes incorporating FtsA and FtsZ-YFP showed a variety of distributions, including foci and linear arrays. A small fraction of liposomes had obvious Z rings. These Z rings could constrict the liposomes and in some cases appeared to complete the division, leaving a clear septum between the two daughter liposomes. Because complete liposome divisions were not seen with FtsZ-mts, FtsA may be critical for the final membrane scission event. We demonstrate that reconstituted cell division machinery apparently divides the liposome in vitro.

Keywords: bacteria, cytoskeleton, tubulin

Bacterial cytokinesis is generated by a complex ring-shaped structure comprising more than a dozen proteins. It is called a Z ring because the primary cytoskeletal framework is made by filamentous temperature-sensitive Z (FtsZ). FtsZ has a globular core homologous to tubulin, and at its C terminus there is an ∼50 amino acid unstructured peptide linker, followed by an ∼17 amino acid peptide that binds FtsA (see ref. 1 for a review of FtsZ). FtsA has a C-terminal amphipathic helix that inserts into the membrane, and it therefore serves to tether FtsZ to the membrane. FtsA is also the primary dock for most of the downstream division proteins. FtsA proteins from Streptococcus pneumoniae and Thermotoga maritima have been shown to assemble into actin-like filaments in vitro (2, 3). FtsA from Escherichia coli has been described as “recalcitrant” and difficult to work with in vitro (4). However, a mutant termed FtsA* has been shown to facilitate cell division in vivo (5, 6) and to be amenable to in vitro experiments (7).

We previously achieved the reconstitution of Z rings in vitro using an engineered construct FtsZ-YFP (yellow fluorescent protein)-mts, where mts is an amphipathic helix that can tether FtsZ directly to the membrane, bypassing FtsA (8). The Z rings assembled spontaneously when FtsZ-YFP-mts was incorporated with GTP into multilamellar tubular liposomes, and they generated a constriction force without the need for any other protein. The constriction force generated invaginations of the liposome wall but not a complete septation. The lack of complete septation may be due to the thickness of the wall in the multilamellar liposomes and/or an intrinsic inability of FtsZ-YFP-mts to achieve complete sepation.

In the present study, we developed a unique reconstitution system that let us answer three major questions. (i) Can we achieve reconstitution in unilamellar liposomes? (ii) Can we achieve reconstitution using the natural two-protein system, where FtsA tethers FtsZ to the membrane? (iii) Can we achieve complete division and septation of liposomes?

Results

We used the previously developed emulsion method (9) to obtain unilamellar spherical liposomes with FtsZ (and FtsA* when wanted) inside (Fig. S1 A and B). However, there were problems in observing the structures in the light microscope when suspended in a simple aqueous solution. First, liposomes floating in solution were constantly moving, making it difficult to photograph. Second, liposomes often burst when they contacted the glass surface. Third, it was difficult to achieve distortion into a tubular shape, which is preferable for formation of Z rings. Although several sophisticated methods have been proposed using laser tweezers and/or micromanipulators (10, 11), we found that simply mixing the liposomes with a low concentration of agarose resolved all of these problems. We mixed the liposome solution with agarose immediately after formation by the emulsion method. Because the low concentration of agarose hardened slowly at room temperature, the mixture easily spread in the narrow space between the slide glass and the coverslip. When the agarose hardened, the liposomes were motionless, and clear images could be acquired (Fig. 1). The shear induced during the spreading distorted the liposomes into a variety of shapes, including spherical and tubular shapes as shown below.

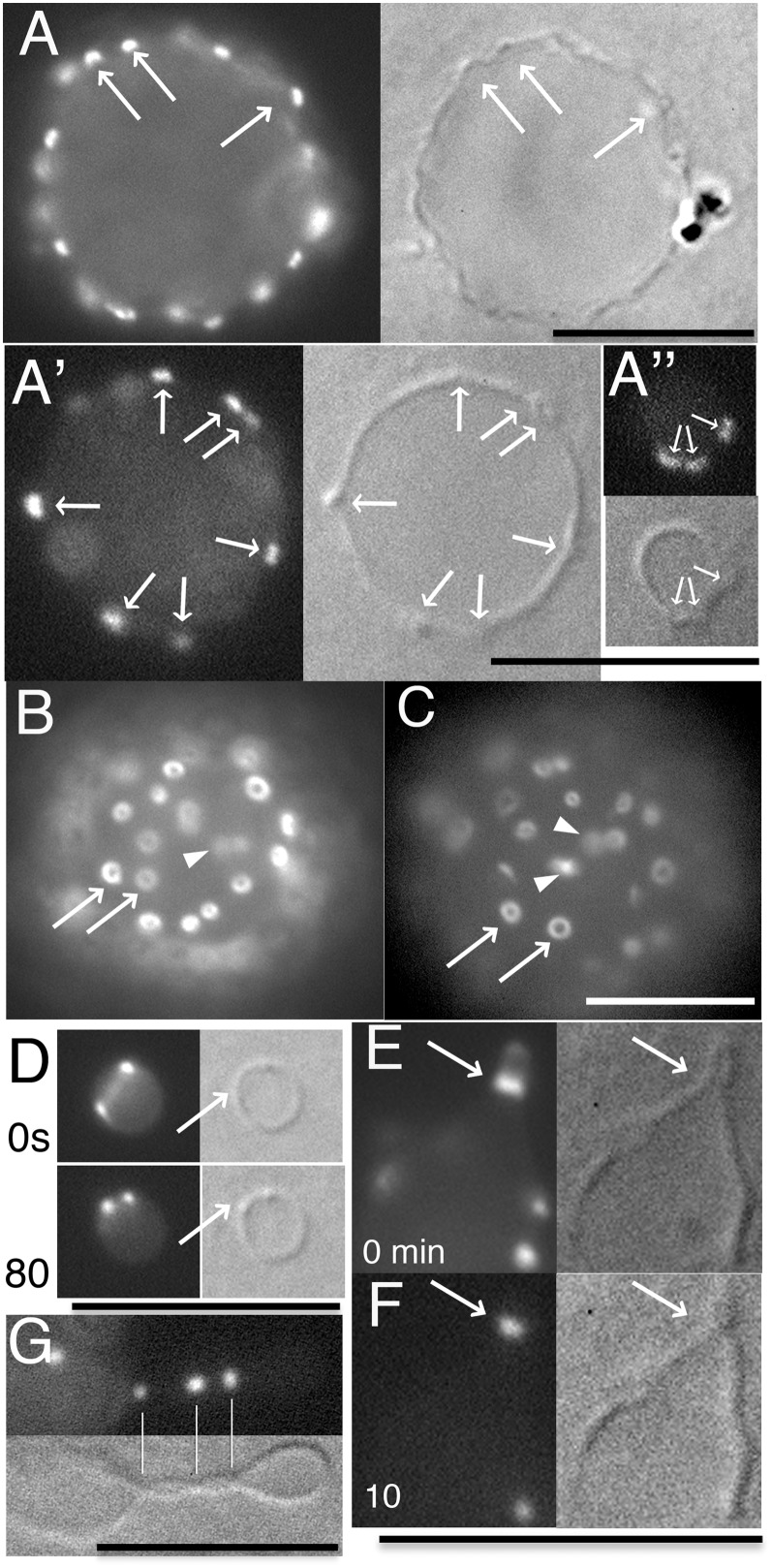

Fig. 1.

Z rings and related structures formed by FtsZ-YFP-mts in unilamellar liposomes, without FtsA*, immobilized in a soft agarose gel. (A, A′, and A″) The focus is on a plane through the middle of the liposome. The DIC image (Right) shows many membrane protrusions, which are concave depressions as seen from inside the liposome. The fluorescence signal shows small patches of FtsZ-YFP-mts at these sites (arrows). A′ and A″ show vesicles with more sparse patches to more easily identify them with membrane protrusions. (B) The focus is on the upper surface of the same liposome as in A. Small Z rings are seen on the inner surface of liposome (arrows). Patches (arrowheads) were also observed. (C) Another liposome viewed en face, showing Z rings and patches. (D) A Z ring on the inner surface of a small liposome appeared as two bright dots connected by a faint line. After 80 s, the Z ring had decreased in diameter. The bright dots (Z ring seen edge on) were also visible in the DIC images (arrows). (E) A Z ring formed in a cylindrical protrusion. (F) The Z ring shown in E constricted the protrusion 10 min later. The arrows indicate Z rings and constriction sites. (G) FtsZ foci in this thin tubular extension are exactly localized at the membrane kissing points. These Z rings are smaller than the 250-nm resolution of the light microscope. In all experiments, liposomes contained 7 µM FtsZ-YFP-mts with 1 mM GTP. (Scale bar, 10 µm.)

Z-Ring Assembly and Membrane Bending by FtsZ-YFP-mts.

We first applied this agarose method to FtsZ-YFP-mts inside large spherical unilamellar liposomes. We were able to acquire much clearer images of the patches of FtsZ-mts on the inner surface of liposomes (Fig. 1A) compared with those without agarose (Fig. S1D). These patches depended on FtsZ polymerization, as we previously described (Fig. S1C). When imaged at the equator of the liposome, the patches coincided with bending distortions of the membrane (Fig. 1A, arrows). The bending produced projections toward the outside of the liposome, which corresponded to concave depressions, as viewed from the inside of the liposome, similar to the concave depressions formed on the outside of liposomes in our previous study (12). This correlation is more easily seen in liposomes with a small number of patches (Fig. 1 A′ and A″). Importantly, when we imaged these patches en face, on the upper surface of large spherical liposomes, we saw that many of them had the shape of a small rings, ranging from 600 to 1,500 nm in outside diameter and with a hole in the center. The frequency of these rings in the en face section suggests that many of the patches seen at the equator (Fig. 1A) are rings seen edge on. We also found some smaller dots, which may be small rings where the central hole is not resolved. In addition to the rings, there were some amorphous patches similar to those we have seen before on the outside surface of liposomes (Fig. 1 B and C, arrowheads) (12). Some patches were elongated and may be precursors of longer bundles that develop under some conditions (Fig. 2). These small Z rings appear to maintain the membrane bending into concave depressions. One possible scenario is that the FtsZ initially forms patches, with short protofilaments running in several directions, and these initiate the bending into concave depressions. These patches then reorganize into rings that run around the periphery of the depression and maintain its bending.

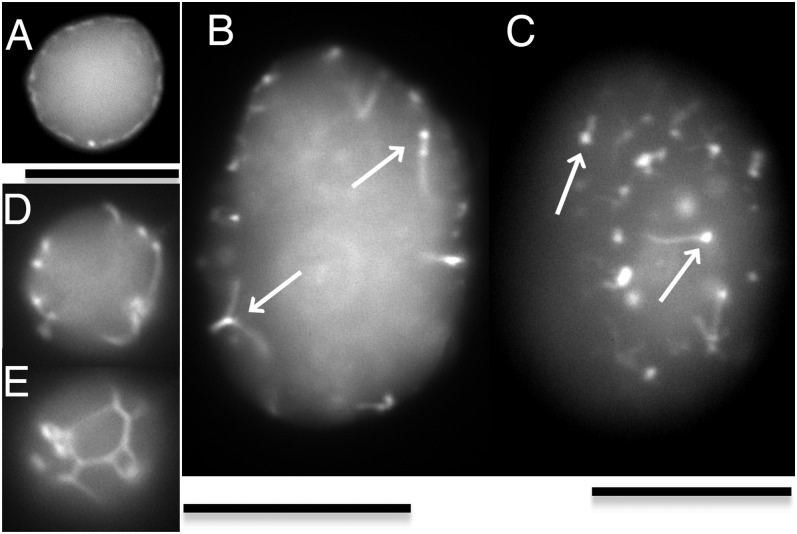

Fig. 2.

Localization of FtsZ-YFP assembled with FtsA* in unilamellar liposomes immobilized in a soft agarose gel. (A) FtsZ-YFP associated with the membrane at small puncta and more diffusely. Much of the diffuse fluorescence in the center of the liposome may be soluble FtsZ-YFP. (B) FtsZ-YFP filament bundles growing from foci (arrows). The image is focused on a plane through the middle of the liposome, and the bundles grow mostly into the liposome center. (C) This is the same liposome in B but the focus is on the upper surface. Some bundles appear to grow along the liposome membrane. (D and E) The FtsZ-YFP bundles grow and connect, forming a network on the membrane. The focus is on a plane through the middle of the liposome for the upper panel and on the upper surface of the same liposome for the lower panel. In one set of quantitative experiments, the diffuse membrane binding distribution shown in A was seen in 2.5% (5/200) of liposomes. The bundle formation shown in B–E was seen in 14% of liposomes (28/200). Almost all liposomes had foci on the membrane and/or inside liposomes. Liposomes contained 7 µM FtsZ-YFP, 7 µM FtsA*, 2 mM GTP, and 0.5 mM ATP. (Scale bars, 10 µm.)

Fig. 1D shows a small vesicle with a single Z ring, appearing as two bright dots (the Z ring seen in projection at the edge) connected by a thin line. This Z ring appears to constrict from 0 to 80 s, but it does not constrict the vesicle. Rather it seems to slide along the side of the vesicle to achieve the smaller diameter. Its more constricted form may approach the structure of the small rings seen en face in Fig. 1 B and C, although it is not producing a concave depression.

Some of the liposomes adopted thin, tubular extensions, in which we often found Z rings, generally at sites of constriction (Fig. 1E). In the most constricted rings, we could not resolve the gap of the membrane wall, indicating that the diameter of the constriction is less than the 250-nm resolution of the light microscope (Fig. 1G). The fluorescence from FtsZ-mts was exactly localized as a spot at the constriction site. We also found skinny unilamellar tubular liposomes that had multiple small Z rings. These Z rings were localized at kissing points of the membrane constrictions in the differential interference contrast (DIC) image (Fig. 1G; Fig. S2). Therefore, we think that Z rings produced by FtsZ-mts are able to constrict to less than 250 nm, but may not achieve full division.

Z-Ring Assembly, Vesicle Constriction, and Complete Septation by FtsZ Plus FtsA*.

To reconstruct more natural Z rings in liposomes, we turned to a mixture of FtsZ and FtsA, which is the native membrane tether for FtsZ (13). We were unable to obtain useful reconstitutions using WT FtsA. The mutant FtsA* (5, 7, 14) gave much better results as an expression protein and was used for all studies. FtsZ-YFP (which has YFP following the C-terminal, FtsA-binding peptide) showed a variety of localization patterns when assembled inside liposomes with FtsA*, ATP, and GTP. In 2.5% of liposomes, FtsZ associated with the membrane, most likely through FtsA*, and was evenly distributed on the membrane, with some more intense foci (Fig. 2A). In the same conditions, 14% of liposomes showed FtsZ assembled into bundles (Fig. 2 B and C). These bundles often sprouted from foci, which might be nucleation centers of FtsZ filaments. The bundles grew into the liposome interior (Fig. 2B) or along the liposome membrane (Fig. 2C). In some liposomes, these bundles connected with each other and formed net structures on the inner surface of liposomes (Fig. 2 D and E). These net structures formed by FtsZ bundles did not show constrictions and may have a substructure different from Z rings. Without GTP, we did not see any significant structure except some dots or rarely small rod like structures on the membrane.

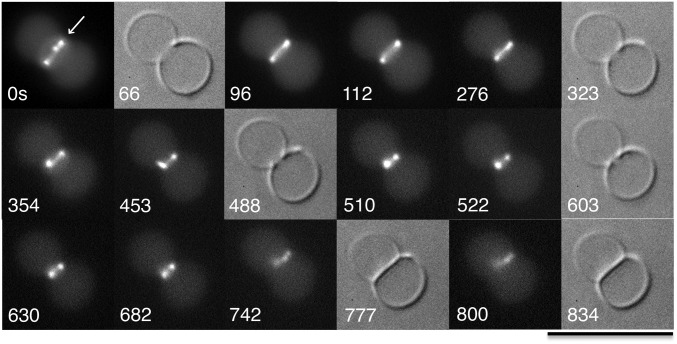

A small fraction of liposomes had Z rings that were localized at constriction sites. Some of these Z rings actually showed continued constriction in time-lapse recordings. Our best example is shown in Fig. 3. A large diameter Z ring, which was initially located at the moderately constricted site, continued to constrict and developed a highly constricted invagination within several minutes. At 488 and 603 s, the DIC images still show a narrow gap between the invaginating edges, and at 510, 522, 630, and 682 s, the fluorescence shows the two-dot structure characteristic of a Z ring. At 742 s, however, the two-dot structure has dispersed and shifted to one side, and at 777 s, the DIC image shows that the gap has been replaced by a continuous septum. This liposome appears to have completed division. Probably the division was completed between 682 and 742 s. Two additional examples of apparent complete division are shown in Figs. S3 and S4 and are described in the figure captions.

Fig. 3.

Time lapse recording of liposome division by FtsZ-YFP plus FtsA*. The recording started with a Z ring (arrow) at a moderate constriction at time 0. The constriction deepened over time. There is a clear gap at the constriction site at 603 s, but at 777 s, the gap is replaced with a complete septum. The liposome contained 7 µM FtsZ-YFP, 7 µM FtsA*, 2 mM GTP, and 0.5 mM ATP. (Scale bar, 10 µm.)

Quantification of results has been difficult because of the low frequency of Z rings assembled in liposomes and their highly dynamic property. However, in one large experiment, we found 42 Z rings and followed them over time, with the following results. Fourteen Z rings constricted to apparently complete septation; 14 Z rings constricted the liposomes but not to complete septation; and 24 Z rings were located at a visible constriction site that did not change their diameters during the ∼20 min of observation. In another large experiment, we checked 400 liposomes to see if Z rings were formed. These liposomes were checked within 20 min after starting the reaction in order not to miss Z rings that had already progressed to a high level of constriction. We found eight Z rings, meaning that 2% liposomes had a Z ring. Therefore, 1.3% liposomes [(14 + 14)/42 × 2%] showed progressive constriction during the observation.

To thoroughly confirm that the Z ring is generating the liposome division, we followed negative controls containing FtsZ and FtsA* but no GTP. We imaged more than 200 liposomes for 1 h. Most liposomes showed a static structure, and a few showed small shape changes, examples of which are shown in Fig. S5. The clearly progressing constrictions or divisions as shown in Fig. 3 and Figs. S3 and S4 were never observed, indicating that liposome constrictions and division are generated only by active Z rings, requiring GTP.

When GTP was replaced with the GMPCPP, a slowly hydrolyzable GTP analogue, we found large foci but no structures like Z rings. We then tested the effect of omitting ATP, which is required for FtsA* assembly (2, 3). Recruitment of FtsZ-YFP to the membrane was reduced without ATP, perhaps because the affinity of monomeric FtsA* to the FtsZ filaments and/or the membrane is lower than that of polymerized FtsA. We did not find any Z rings in liposomes in the absence of ATP.

Discussion

Using our unique system to observe Z rings in unilamellar vesicles, we successfully addressed the three questions raised in the Introduction. (i) The membrane-targeting FtsZ construct FtsZ-YFP-mts assembled patches on the inside of the liposome. When the patches were viewed en face, on the top surface of the larger vesicles, many appeared to be small Z rings, ∼600–1,500 nm in diameter, parallel to the plane of the membrane. These small Z rings did not achieve division but seemed to generate concave bending of the membrane, as viewed from the inside of the liposome. Additionally, the FtsZ-YFP-mts appeared able to generate Z rings that constricted when confined to smaller diameter tubular liposomes. (ii) The natural, two-protein system of FtsZ plus FtsA* produced small patches and elongated bundles of FtsZ attached to the membrane, presumably tethered via the FtsA*. (iii) Most importantly, the FtsZ-FtsA* was able to produce Z rings that encircled liposomes and occasionally achieved complete constriction and septation.

Reconstitution of Z rings in giant unilamellar vesicles, using the two-protein system FtsA and FtsZ, has been attempted previously (15). FtsA alone localized to the walls of the liposome; FtsZ alone formed small clumps and some fibers, dispersed in the vesicle interior and adherent to the membrane. When FtsZ and FtsA were mixed, they colocalized to fibers and clumps in the interior of the vesicle. The FtsZ appeared to dislodge the FtsA from the membrane. The failure to form Z rings in this study might be attributed to a number of experimental differences. The previous study used wild-type FtsA rather than the more tractable mutant FtsA* that we found important. It used a fivefold excess of FtsZ, whereas we had the best results with from half to equimolar FtsZ against FtsA. Finally, it incorporated 50 mg/mL Ficoll in the reconstitutions, a crowding agent that may cause the FtsZ protofilaments to associate into bundles. These bundles, sometimes appearing as clumps, may have prevented the assembly of the much thinner ribbons of protofilaments that constitute Z rings.

Although both FtsZ-YFP-mts and FtsZ-YFP/FtsA* formed Z rings in unilamellar liposomes and generated constriction force, they behaved differently. First, unlike FtsZ-YFP-mts, FtsZ-YFP/FtsA* did not form multiple concave depressions and small Z rings on the surface of large liposomes. Second, complete division was not observed with the membrane-targeted FtsZ. These results suggest that the FtsA* plays a role in organizing Z-ring assembly and in the final scission event. These events may involve assembly of FtsA* into polymers on the membrane, which serve to organize FtsZ protofilaments (2, 3). Another possibility is that the bond between FtsA* and the C-terminal peptide of FtsZ, which was reported to be very weak, Kd ∼ 50 µM (3), may be more readily reversible than the direct insertion of the mts of FtsZ-YFP-mts into the bilayer. This weak interaction may permit the disassembly of the Z ring in the final stage of division. This situation may also explain why FtsZ-YFP-mts can form multiple concave depressions and Z rings on the almost flat surface of large liposomes, whereas FtsZ-YFP/FtsA* cannot.

There are several possible reasons for the low frequency of Z-ring assembly and constriction. In our liposome system, it takes about 10 min from the time of liposome formation to observation under the microscope. Some liposomes might have finished division within this period. However, the most likely impediment is the size and shape of the liposomes, which was not easily controlled in our soft agarose gels. Many of the liposomes were up to 50 µm diameter, which is much larger than the maximum diameter of ∼5 µm that we had previously observed for Z-ring assembly in tubular liposomes (8). The shape of the liposome is probably also an important factor, with an elongated shape being more favorable for Z-ring assembly, constriction and division.

The surface area of each liposome in our system is fixed. If a spherical liposome divided into two equal spheres, the total surface area would have to be equal to that of the mother liposome. This situation would require that the total volume of the daughter liposomes be reduced by 30%. Because the lipid bilayer is impermeable to salt, this would cause a large increase in osmotic pressure in our buffer condition. This increase may stall Z-ring constriction. However, liposomes with an elongated or tubular shape may avoid the osmotic pressure increase: one precise tubular geometry can divide into two identical spheres conserving both total surface area and total volume (16). In this case, the Z ring would only need to generate a force sufficient to bend the membrane. In our system, the agarose gel may impose additional constraints. If division took place after the agarose gel had hardened, the expanding daughter spheres/shrinking parental tube would need to compress/stretch the gel, and this would require significant force. It is likely in our experiments that the initial constriction and accompanying shape change takes place before the gel hardens, minimizing the need for this extra force. We note that the liposomes are frequently not perfect spheres but asymmetric (Fig. S4), which could allow progression of the septum with minimal further compression/stretching of the gel.

The constraints of constant surface area and volume are averted in living cells because they are able to assemble new membrane that can accommodate the increased volume, as well as the formation of a septum. Indeed, there are certain cells that normally use FtsZ, but can be converted to cell wall–less L forms, which achieve division in the complete absence of FtsZ (17, 18). We have suggested that these divisions may be affected by an excess production of cell membrane, which could produce invaginations that eventually fuse to divide the cell (19). Recent studies have shown that membrane fluidity plays a crucial role in the division of these L forms and suggested that biophysical processes of the membrane alone might have been sufficient for the division of primitive cells (20, 21). The FtsZ-FtsA system greatly increases the efficiency of the process and is able to achieve division in the absence of excess membrane synthesis.

Materials and Methods

Protein Preparation.

The C-terminal YFP (Venus) fusion of FtsZ (FtsZ-YFP) and membrane targeted FtsZ (FtsZ-YFP-mts) were prepared as previously described (8, 22). Briefly, the soluble fraction of FtsZ-YFP or FtsZ-YFP-mts was precipitated with 30% saturated ammonium sulfate followed by anion exchange chromatography on a resource Q column.

FtsA-R286W (FtsA*) was expressed in C41 cells [derivative of BL21 (23)] from pWM1690, which was provided by William Margolin (University of Texas-Houston Medical School, Houston, TX) (7). This plasmid adds a His6-T7 tag at the N terminus. An optical density at 600 nm = 0.5, cells were induced overnight with 1 mM isopropyl beta-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 37 °C. Cells were collected by centrifugation and suspended in buffer A (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.9, 50 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA) with 400 µg/mL lysozyme. After two cycles of freeze-thaw, the cells were sonicated followed by centrifugation for 20 min at 32,000 rpm (rotor Ti41.2; Beckman). The pellet was suspended in buffer B (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.9, 350 mM KCl, 10% glycerol), containing 1% Triton X-100. This suspension was centrifuged for 20 min at 32,000 rpm (rotor Ti41.2; Beckman), and the supernatant was collected. The supernatant was applied to a Talon column, washed with buffer B containing 1% Triton X-100, and then extensively washed with buffer B without Triton X-100. FtsA* was eluted with buffer B containing 160 mM imidazole. The total yield was about 10 mg FtsA* from 1 L bacterial culture. DTT was added to 0.1%, and the protein was stored at −80 °C.

All proteins were dialyzed in polymerization buffer, HMKCG [50 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 7.7, 5 mM MgAc2, 300 mM KAc, 50 mM KCl, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol] containing 0.1% DTT. FtsA* was centrifuged after dialysis to remove precipitated protein. FtsA* lost activity after multiple freeze-thaw cycles in HMKCG. Protein concentrations were determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay using BSA as a standard for FtsA*. YFP absorption was used to determine concentrations of FtsZ-YFP and FtsZ-YFP-mts as previously described (22).

Liposome Preparation and Observation.

We used the emulsion method to prepare unilamellar liposomes (9). Phosphatidylcholine (PC) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-{phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)} (DOPG) dissolved in methanol at 10 mg/mL were mixed at a 4:1 volume ratio. Twenty-five microliters of the mixture in a microtube was dried with air current followed by the addition of 250 µL of mineral oil. To disperse phospholipid in mineral oil, the mixture was sonicated 20 times for 2 s and then left at room temperature for 5 h. The FtsZ-YFP/FtsA* assembly reaction was prepared in a microtube. The typical condition was 7 µM FtsZ-YFP, 7 µM FtsA*, 2 mM GTP, 0.5 mM ATP, and 0.05% DTT in HMKCG. We placed 5 µL of this reaction solution in 125 µL of the mineral oil and phospholipid mixture described above and mixed vigorously to form an emulsion. This emulsion mixture contained small aqueous micelles of FtsZ-YFP and FtsA, surrounded by a lipid monolayer and suspended in mineral oil. This 130-µL oil suspension was layered on 50 µL of HMKCG buffer as an external feeding solution, followed by low speed centrifugation (1400 × g for 3 min; Costar microcentrifuge). When they passed through the lipid monolayer at the boundary between the oil and aqueous phases, the micelles became unilamellar liposomes, with a single lipid bilayer containing FtsZ-YFP and FtsA* (9). Twenty microliters of 1% agarose in HMKCG at 60–65 °C was added to 50 µL of the unilamellar liposomes and quickly mixed before placing on a glass slide. A 22 × 60-mm coverslip was put on top to spread the solution it before it hardened. If the 7 µM FtsZ-YFP is hydrolyzing GTP at 5 per min, the 2 mM GTP would last about 60 min. The liposomes were observed by DIC and fluorescent microscopy as previously described (12). Focus was adjusted in DIC before taking fluorescent images.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM66014.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1222254110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Erickson HP, Anderson DE, Osawa M. FtsZ in bacterial cytokinesis: Cytoskeleton and force generator all in one. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2010;74(4):504–528. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00021-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lara B, et al. Cell division in cocci: Localization and properties of the Streptococcus pneumoniae FtsA protein. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55(3):699–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szwedziak P, Wang Q, Freund SM, Löwe J. FtsA forms actin-like protofilaments. EMBO J. 2012;31(10):2249–2260. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martos A, et al. Isolation, characterization and lipid-binding properties of the recalcitrant FtsA division protein from Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geissler B, Elraheb D, Margolin W. A gain-of-function mutation in ftsA bypasses the requirement for the essential cell division gene zipA in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(7):4197–4202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0635003100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard CS, Sadasivam M, Shiomi D, Margolin W. An altered FtsA can compensate for the loss of essential cell division protein FtsN in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64(5):1289–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beuria TK, et al. Adenine nucleotide-dependent regulation of assembly of bacterial tubulin-like FtsZ by a hypermorph of bacterial actin-like FtsA. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(21):14079–14086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808872200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osawa M, Anderson DE, Erickson HP. Reconstitution of contractile FtsZ rings in liposomes. Science. 2008;320(5877):792–794. doi: 10.1126/science.1154520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noireaux V, Libchaber A. A vesicle bioreactor as a step toward an artificial cell assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(51):17669–17674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408236101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inaba T, et al. Formation and maintenance of tubular membrane projections require mechanical force, but their elongation and shortening do not require additional force. J Mol Biol. 2005;348(2):325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans EA. Minimum energy analysis of membrane deformation applied to pipet aspiration and surface adhesion of red blood cells. Biophys J. 1980;30(2):265–284. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(80)85093-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osawa M, Anderson DE, Erickson HP. Curved FtsZ protofilaments generate bending forces on liposome membranes. EMBO J. 2009;28(22):3476–3484. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pichoff S, Lutkenhaus J. Tethering the Z ring to the membrane through a conserved membrane targeting sequence in FtsA. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55(6):1722–1734. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geissler B, Shiomi D, Margolin W. The ftsA* gain-of-function allele of Escherichia coli and its effects on the stability and dynamics of the Z ring. Microbiology. 2007;153(Pt 3):814–825. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/001834-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiménez M, Martos A, Vicente M, Rivas G. Reconstitution and organization of Escherichia coli proto-ring elements (FtsZ and FtsA) inside giant unilamellar vesicles obtained from bacterial inner membranes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(13):11236–11241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.194365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terasawa H, Nishimura K, Suzuki H, Matsuura T, Yomo T. Coupling of the fusion and budding of giant phospholipid vesicles containing macromolecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(16):5942–5947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120327109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leaver M, Domínguez-Cuevas P, Coxhead JM, Daniel RA, Errington J. Life without a wall or division machine in Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 2009;457(7231):849–853. doi: 10.1038/nature07742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lluch-Senar M, Querol E, Piñol J. Cell division in a minimal bacterium in the absence of ftsZ. Mol Microbiol. 2010;78(2):278–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erickson HP, Osawa M. Cell division without FtsZ—a variety of redundant mechanisms. Mol Microbiol. 2010;78(2):267–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mercier R, Domínguez-Cuevas P, Errington J. Crucial role for membrane fluidity in proliferation of primitive cells. Cell Rep. 2012;1(5):417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mercier R, Kawai Y, Errington J. Excess membrane synthesis drives a primitive mode of cell proliferation. Cell. 2013;152(5):997–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osawa M, Erickson HP. Chapter 1 - Tubular liposomes with variable permeability for reconstitution of FtsZ rings. Methods Enzymol. 2009;464:3–17. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)64001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miroux B, Walker JE. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: Mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J Mol Biol. 1996;260(3):289–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.