Abstract

Magnetic field fluctuations arising from fundamental spins are ubiquitous in nanoscale biology, and are a rich source of information about the processes that generate them. However, the ability to detect the few spins involved without averaging over large ensembles has remained elusive. Here, we demonstrate the detection of gadolinium spin labels in an artificial cell membrane under ambient conditions using a single-spin nanodiamond sensor. Changes in the spin relaxation time of the sensor located in the lipid bilayer were optically detected and found to be sensitive to near-individual (4 ± 2) proximal gadolinium atomic labels. The detection of such small numbers of spins in a model biological setting, with projected detection times of 1 s [corresponding to a sensitivity of ∼5 Gd spins per Hz1/2], opens a pathway for in situ nanoscale detection of dynamical processes in biology.

Keywords: nitrogen-vacancy center, biophysics, nanomagnetometry

The development of sensitive and highly localized probes has driven advances in our understanding of the basic processes of life at increasingly smaller scales (1). In the last decade there has been a strong drive to expand the range of probes that can be used for studying biological systems (2–6), with emphasis on the detection of atoms and molecules in nanometer-sized volumes to gain access to information that may be hidden in ensemble averaging. However, at present there are no nanoprobes suitable for directly sensing the weak magnetic fields arising from small numbers of fundamental spins in nanoscale biology, occurring naturally (e.g., free radicals) or introduced (e.g., spin labels). These can be a rich source of information about processes at the atomic and molecular level. Magnetic resonance techniques such as electron spin resonance (ESR) have played an important role in the development of our understanding of membranes, proteins, and free radicals (7); however, ESR sensitivity and resolution are fundamentally limited to mesoscopic ensembles of at least 107 spins with a sensitivity of ∼2 × 109 spins per Hz1/2 (8). In a typical ESR application, small electron spin label moieties are attached to the system of interest and their environment is investigated through spin measurements on the labels. Because of the large ensemble required, nanoscopic detail at the few-spin level can be lost in the averaging process. Recently, magnetic resonance force microscopy techniques have demonstrated single-spin detection (9–11), but these require cryogenic temperatures and vacuum. Here, we demonstrate a nanoparticle probe––a nitrogen-vacancy spin in a nanodiamond––which is situated in the target structure itself and acts as a nanoscopic magnetic field detector under ambient conditions with noncontact optical readout. We use this probe to detect near-individual spin labels in an artificial cell membrane at a projected sensitivity of ∼5 Gd spins per Hz1/2, effectively bridging the gap between traditional ESR ensemble-based techniques and the ultimate goal of few-spin nanoscale detection under biological conditions.

Results and Discussion

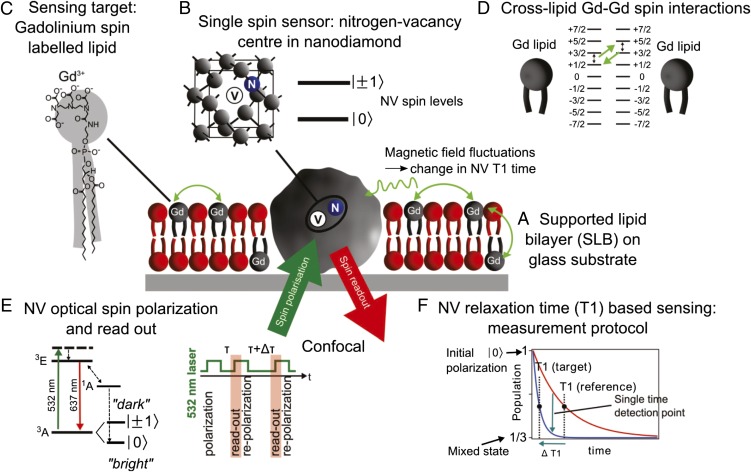

The overall setup of our experiment is shown schematically in Fig. 1A. The nanoparticle probe is the single spin of a nitrogen-vacancy (NV) center contained in a nanodiamond particle (Fig. 1B). NV nanodiamonds are attractive nanoprobes for biology as they exhibit low toxicity and are photostable (12–14). Here, we investigate the magnetic field sensing capabilities of the NV center in a biological context. Around these NV nanodiamonds we formed a supported lipid bilayer (SLB) on a glass substrate. The SLB was created with lipids labeled with Gd3+, a common MRI contrast agent with spin 7/2 (Fig. 1C), which produces characteristic magnetic fluctuations in the lipid environment (Fig. 1D) and form our detection target. The ground state of the NV center has a zero-field splitting of D = 2.87 GHz between the |0〉 and |±1〉 spin levels and optical-based spin-state readout is possible due to the significantly lower fluorescence of the |±1〉 compared with the |0〉 state (15) (Fig. 1E). These properties have led to demonstrations of dc and ac magnetic field detection using single NV spins (16–18), and wide-field detection schemes using ensembles of NV centers (19–22). For biological applications, where atomic level processes produce magnetic field fluctuations, it has been proposed that changes in the quantum decoherence of the NV spin could provide a more sensitive detection mechanism (23–25). Ensemble relaxation-based imaging has been demonstrated with subcellular resolution and detection of ∼103 spins (26). Toward the goal of using single NV spins as in situ nanomagnetometer probes in biology, quantum measurements on single NV spins have been carried out in a living cell (27), and with the recent detection of external spins in well-controlled environments (28–33), the critical milestone is to demonstrate nanoscopic external spin detection in a biological context. Here we achieve this with near-individual spin sensitivity by monitoring the relaxation time (T1) of a single NV spin probe (Fig. 1 E and F) embedded in the SLB target itself. In addition, our results indicate that the NV spin is sensitive to cross-lipid magnetic fluctuations arising from the small number of Gd labeled lipids in the SLB in the vicinity of the nanodiamond (Fig. 1 A and D).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of nanoscopic detection of spin labels in an artificial cell membrane using a single-spin nanodiamond sensor. (A) SSLB is formed around a nanodiamond immobilized on a glass substrate. (B) Nanodiamond contains a single NV optical center which acts as a single-spin sensor by virtue of the magnetic levels in the ground state. (C) Gd spin-labeled lipids are introduced into the SLB. (D) Magnetic field fluctuations arising from Gd spin labels affect the quantum state of the NV spin, measured through the NV relaxation time, T1. (E) Electronic energy structure of the NV center showing the fluorescence cycle and optical spin readout of the spin states |0〉 and |±1〉, and the protocol for the T1 measurement. (F) Schematic illustration of the T1 measurement. The relaxation of the NV spin in the target environment is compared to that in the reference environment. Measurement at a single time point in the evolution allows faster detection.

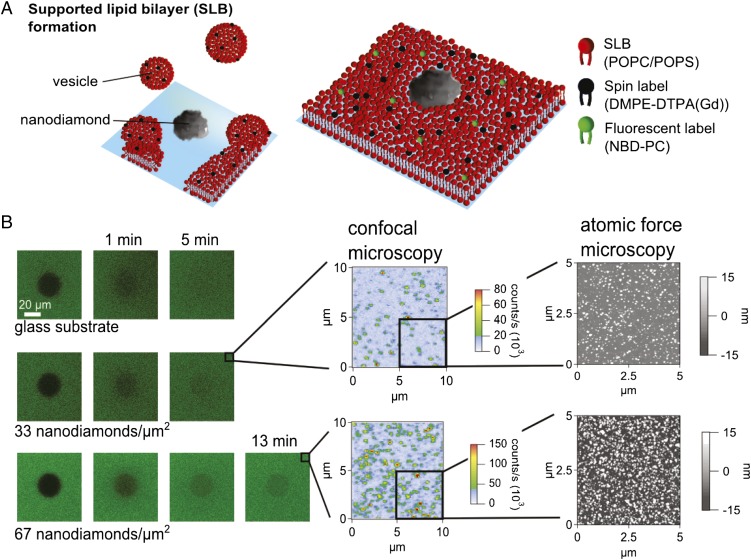

The SLB was formed on the nanodiamond–glass substrate in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) solution via the vesicle fusion technique (34) (Fig. 2A), and characterized by both fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Fig. 2B; SI Text). AFM investigations showed that the SLB formed mainly around the nanodiamond particles (mean size = 15.9 ± 9.5 nm). The T1 time of the NV spin was measured by optically polarizing into the |0〉 state and measuring the probability P0(t) of finding the NV in the |0〉 state at a later time t through spin-state fluorescence contrast. In a low background field the |±1〉 spin states of the NV are approximately degenerate so the P0(t) decays as

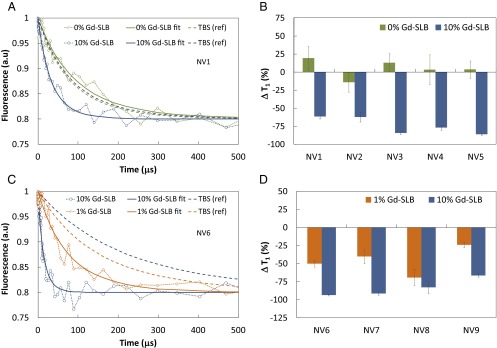

This form is a consequence of the three-state nature of the NV spin manifold and the broad spectrum of the target spin bath (see SI Text for the derivation). Fig. 3A (green dashed curve) shows P0(t) (normalized fluorescence) for a single NV center (NV1) under the TBS control conditions. Fitting to Eq. 1, we obtain a reference relaxation time T1[TBS] = 117 ± 11 μs. T1[TBS] includes intrinsic nanodiamond sources of relaxation such as N donors (electron spin bath), and 13C spins (nuclear spin bath), but is dominated by surface electronic spins fluctuating in the gigahertz regime. After the formation of a SLB without Gd spin labels (under the same TBS conditions), the measurement was repeated on the same NV (green data points) to give T1[SLB] = 139 ± 18 μs, showing no statistically significant change for the unlabeled lipid case. Removal of the SLB, which included a 2-min oxygen plasma-etching step, was followed by a new TBS reference T1 measurement (blue dashed curve). Upon formation of the SLB with Gd spin-labeled lipids at 10% (wt/wt) concentration (blue data points), we observed a 61% reduction in the NV relaxation time to T1[SLB:Gd] = 48 ± 3 μs.

Fig. 2.

Formation and characterization of SLB on nanodiamond/glass substrates. (A) SLBs were formed by the vesicle fusion technique and characterized by FRAP. (B) Confocal images of FRAP measurements directly after the bleaching cycle for a SLB+10% (wt/wt) of the Gd spin label and 1% (wt/wt) of a fluorescent label. For characterization, three different substrate conditions were investigated. Confocal and AFM images show nanodiamond density and size distribution.

Fig. 3.

Detection of spin-labeled lipids in a SLB using the T1 time of single NV spins in nanodiamonds. (A) Relaxation of the spin of a single NV center (NV1) in a nanodiamond in a SLB without spin labels (green) and in a SLB with 10% (wt/wt) Gd spin labels (blue). (B) Percentage change in T1 (relative to TBS) of five single NV spins (NV1–NV5) in distinct nanodiamonds: SLB+0% Gd (green) and SLB+10% Gd (blue). (C) Relaxation of the spin of NV6 for SLB+ 10% Gd (blue) and SLB+1% Gd (orange). (D) Concentration dependence of the percentage change in T1 for a set of centers, NV6–NV9. The data in B and C, after fitting to determine the relaxation times, have been scaled to the same asymptotic value for ease of presentation. All error bars represent the fitting uncertainties at the 95% confidence interval. Solid curves are the corresponding fits of the data to Eq. 1 that determine T1. Dashed curves correspond to the fitted data of the corresponding reference TBS measurement before each SLB measurement.

To demonstrate the consistency of the effect, this sequence was performed for five NV centers (NV1–NV5), in distinct nanodiamonds. Fig. 3B shows the percentage changes in the T1 times for all five NV centers relative to their TBS reference values. For the SLB with no spin labels there is no statistically significant change, verifying that the NV T1 relaxation time remains intact under control conditions. For the SLB labeled with 10% Gd the average reduction in the NV T1 relaxation time from the reference value is 74 ± 6%, and is remarkably consistent across the set of nanodiamonds. We next investigated the Gd concentration dependence of the change in the T1 relaxation time. In Fig. 3C the T1 curves of a single NV center (NV6) are given for 10% and 1% Gd concentrations, showing the change in T1 decreasing as the number of proximate Gd spins is reduced. The percentage changes in T1 from the respective TBS reference values as a function of Gd concentration are given in Fig. 3D for another set of four individual NV centers (NV6–NV9), confirming this trend.

To understand these results quantitatively, we consider the quantum evolution of the NV spin in the presence of magnetic field fluctuations arising from the various atomic processes involving the Gd spins in the SLB (SI Text). The characteristic timescales of these fluctuations produce specific changes in the measured T1 relaxation time of the NV spin from the reference value. In terms of external sources of decoherence, the quantum evolution of the NV spin is determined by the overall spectral distribution function  , which is governed by the characteristic environmental magnetic field fluctuation frequency fe. The Gd-labeled lipid environment produces magnetic field fluctuations (due to cross-lipid Gd–Gd spin dipole interactions, motional diffusion of individual Gd-labeled lipids, and intrinsic Gd spin relaxation effects, each with characteristic frequencies

, which is governed by the characteristic environmental magnetic field fluctuation frequency fe. The Gd-labeled lipid environment produces magnetic field fluctuations (due to cross-lipid Gd–Gd spin dipole interactions, motional diffusion of individual Gd-labeled lipids, and intrinsic Gd spin relaxation effects, each with characteristic frequencies  ,

,  , and

, and  , respectively), that each contribute to fe. From

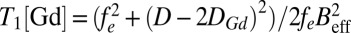

, respectively), that each contribute to fe. From  we obtain the NV relaxation time T1[Gd] due to Gd–lipid effects:

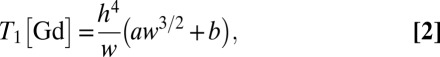

we obtain the NV relaxation time T1[Gd] due to Gd–lipid effects:  , where

, where  is the characteristic Gd–NV dipolar magnetic field interaction, h is the NV depth below the nanodiamond surface, σ is the areal Gd spin density, and DGd is the zero-field splitting parameter of the Gd spin, with the dominant contribution to T1 coming from the 2DGd transition. We note that the 4DGd and 6DGd transitions are too far detuned from D to have any significant effect on T1. We obtain

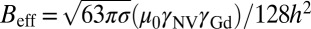

is the characteristic Gd–NV dipolar magnetic field interaction, h is the NV depth below the nanodiamond surface, σ is the areal Gd spin density, and DGd is the zero-field splitting parameter of the Gd spin, with the dominant contribution to T1 coming from the 2DGd transition. We note that the 4DGd and 6DGd transitions are too far detuned from D to have any significant effect on T1. We obtain  by integrating the Gd–Gd dipolar autocorrelation function over a planar SLB distribution to give

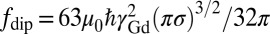

by integrating the Gd–Gd dipolar autocorrelation function over a planar SLB distribution to give  . For the diffusion of Gd lipids in the SLB we obtain

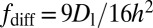

. For the diffusion of Gd lipids in the SLB we obtain  , where Dl is the Gd-lipid diffusion constant. The intrinsic Gd spin relaxation is characterized by

, where Dl is the Gd-lipid diffusion constant. The intrinsic Gd spin relaxation is characterized by  (35). For the NV depths expected in these 16-nm nanodiamonds and Gd concentrations used here, the effect of Gd–Gd interactions on the NV relaxation time dominates over Gd diffusion effects. Expanding around the low Gd density limit we arrive at a theoretical model for the NV relaxation time T1[Gd], due to proximate Gd labeled lipids:

(35). For the NV depths expected in these 16-nm nanodiamonds and Gd concentrations used here, the effect of Gd–Gd interactions on the NV relaxation time dominates over Gd diffusion effects. Expanding around the low Gd density limit we arrive at a theoretical model for the NV relaxation time T1[Gd], due to proximate Gd labeled lipids:

|

where w is the %wt/wt Gd-lipid concentration, and a and b are constants involving the physical parameters D, DGd, and fin (SI Text). Because the nanodiamond surface spins comprise a 2D distribution we also obtain T1[TBS] ∝ h4. Hence there is a cancellation of the depth dependence in the percentage change in relaxation times, ΔT1[SLB:Gd]/T1[TBS], which may explain the uniformity of the effect across the set of NV nanodiamonds shown in Fig. 3B.

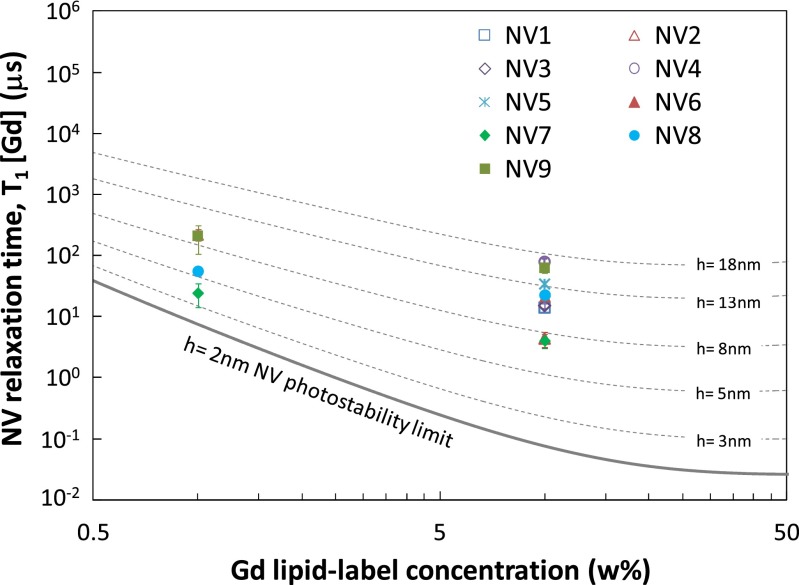

To directly compare our data with Eq. 2, we extract T1[Gd] by subtracting the reference rate (i.e., Γ1[Gd] = Γ1[SLB:Gd] − Γ1[TBS]) and in Fig. 4 plot this quantity for all NV1–NV9 against Gd concentration w. Generally, the data points lie in a NV depth range consistent with the measured AFM nanodiamond size distribution, indicating that we observe T1[Gd] times in broad agreement with those predicted by Eq. 2. The trend to shallower NV depths as we move from 10% → 1% Gd-lipid concentration is consistent with the etching step in the processing of the sample between the 10% and 1% measurements, which is likely to have removed several nanometers of material from the nanodiamonds. However, we note that for low concentrations we also expect some deviation to the scaling in Eq. 2 due to the statistics of low Gd spin numbers.

Fig. 4.

NV relaxation time due to the presence of Gd spin-labeled lipids, T1[Gd], as a function of Gd-lipid concentration (%wt/wt) for all measured centers, NV1–NV9 (data points). Theoretical curves (dashed) based on Eq. 2 are given for a range of NV depths h with a lower bound h = 2 nm corresponding to the photostability limit (36).

The effective number of spins detected, Neff, for a given Gd concentration w is estimated by comparing the rms field expectation 〈B2〉1/2 at the NV contributing to the change in relaxation time integrated over all Gd spins in the membrane, to that of a single Gd spin at distance h, to obtain  (SI Text). Using the NV depth range h ∼ 8 ± 5 nm from the AFM distribution, we arrive at a lower bound estimate of the effective number of spins detected of 4 ± 2 (1% Gd) and 28 ± 24 (10% Gd). Finally, from the data we can determine projected single time-point detection times assuming the reference TBS value has been well characterized and the measured fluorescence contrast is normalized. For the case of NV7, which had a relatively fast value of T1[TBS], to detect the fluorescence change at the 95% CL corresponding to 1% Gd–SLB at a single time point requires a total measurement time of ∼1.3 s (SI Text).

(SI Text). Using the NV depth range h ∼ 8 ± 5 nm from the AFM distribution, we arrive at a lower bound estimate of the effective number of spins detected of 4 ± 2 (1% Gd) and 28 ± 24 (10% Gd). Finally, from the data we can determine projected single time-point detection times assuming the reference TBS value has been well characterized and the measured fluorescence contrast is normalized. For the case of NV7, which had a relatively fast value of T1[TBS], to detect the fluorescence change at the 95% CL corresponding to 1% Gd–SLB at a single time point requires a total measurement time of ∼1.3 s (SI Text).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated nanoscopic magnetic detection of spin labels in an artificial cell membrane using the T1 relaxation time of a single-spin NV nanodiamond probe. Our results for Gd-labeled lipid concentrations down to 1% (wt/wt) correspond to the detection of near-individual Gd spin labels, with projected single time-point detection times of order 1 s. The data are in broad agreement with cross-lipid Gd–Gd spin interactions as the dominant atomic process detected. These results highlight the potential of the NV–nanodiamond system as a nanoscopic magnetic probe in biology, which circumvents the fundamental problems associated with ensemble averaging.

Materials and Methods

Nanodiamond Preparation.

Nanodiamond was purchased from VanMoppes (SYP 0–0.03) and irradiated with high-energy electrons (2 MeV with a fluence of 1 × 1018 electrons per cm2) and vacuum annealed at 800 °C for 2 h at the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (Takasaki, Japan). The powder was heated to 425 °C in air for 3 h, dispersed in water, and sonicated with a high-power sonicator (Sonicator 4000, Qsonica2) for 30 h. The suspension was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 120 s and the supernatant was removed and used as stock suspension. For the adsorption of nanodiamonds, cleaned glass substrates (No. 1, Menzel) were immersed in a 1 mg/mL solution of polyallylamine hydrochloride (70 kDa) in 0.5 M NaCl in Milli-Q water for 5 min. After rinsing with Milli-Q water, the stock nanodiamond suspension was diluted × 50 in Milli-Q water and then applied to the coverslip for 5 min, before rinsing again. The glass substrates were treated in a 40-W oxygen plasma [25% oxygen in argon, 40 standard cubic centimeters per minute (sccm) flow rate] for 5 min to remove the polyelectrolyte from the substrate. AFM in air was performed with an Asylum MFP-3D in tapping mode with cantilevers from Olympus (AC160TS, 42 N/m).

Formation of SLBs.

All chemicals are of analytical grade reagent quality if not otherwise stated. The lipids (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc.) 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (sodium salt) (POPS), and 1-palmitoyl-2–12-[(7-nitro-2–1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)amino]dodecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine were dissolved in chloroform and the spin label 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (gadolinium salt) (DMPE-DTPA(Gd)) was dissolved in the mixture chloroform:methanol:water (65:35:8) (vol:vol:vol). The lipids were mixed in the desired ratios and were dried under a stream of nitrogen for 1 h followed by resuspension in TBS buffer. TBS buffer was prepared by mixing 10 mM Tris(hydroxymethyl)-aminomethane (Sigma-Aldrich Pty. Ltd.) and 150 mM sodium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich Pty. Ltd.) in water with the pH adjusted to 7.4 by stepwise addition of 1 M hydrochloric acid. Milli-Q water [18.2 MΩ and at most 4 ppm total organic carbon (TOC), Millipore] was used throughout. The buffer was filtered through 0.2-μm filters (PALL Acrodisc Syringe Filter) before use. SLBs were formed with vesicles extruded 31 times through two stacked, 100-nm pore-size polycarbonate membranes (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc.) at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL with an exposure time of 1 h (overnight exposure for quantum measurements in liquid cell). The vesicle size was measured by dynamic light-scattering resulting in an average size of 113  3 nm (SD). Before the formation of SLBs, 3 mM

3 nm (SD). Before the formation of SLBs, 3 mM  (

( , Chem-Supply Pty. Ltd.) was added to the buffer solution. This improved the adhesion onto the negatively charged, glass surface (37). After the measurements the liquid cell was cleaned with 2% (vol/wt) of SDS in water and isopropyl alcohol and thoroughly rinsed with water. Before quantum measurements the coverslip was treated in a 40-W oxygen plasma (25% oxygen in argon, 40 sccm flow rate) for 2 min.

, Chem-Supply Pty. Ltd.) was added to the buffer solution. This improved the adhesion onto the negatively charged, glass surface (37). After the measurements the liquid cell was cleaned with 2% (vol/wt) of SDS in water and isopropyl alcohol and thoroughly rinsed with water. Before quantum measurements the coverslip was treated in a 40-W oxygen plasma (25% oxygen in argon, 40 sccm flow rate) for 2 min.

T1 Measurements.

Confocal imaging was performed on a home-built microscope using an oil-immersion objective (100×, Nikon). T1 measurements were performed using a Spincore PulseBlaster card and a Fast ComTech P7889 Multiple-Event Time Digitizer card. Typical measurement time for a full evolution of a T1 curve was 1 h. Spin-relaxation curves were fitted using Eq. 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council under the Centre of Excellence Scheme (project no. CE110001027), the Centre for Neural Engineering (University of Melbourne), European Research Council Project SQUTEC (Spin Quantum Technologies), European Union Project DINAMO (Development of diamond intracellular nanoprobes for oncogen transformation dynamics monitoring in living cells), and the Baden-Wuerttemberg Foundation. S.K. was supported by a Swiss National Science Foundation fellowship PBEZP3-133244. F.C. is supported by the Australian Research Council Australian Laureate Fellowship Scheme (project no. FL120100030).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1300640110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Michalet X, et al. Quantum dots for live cells, in vivo imaging, and diagnostics. Science. 2005;307(5709):538–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1104274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ament I, Prasad J, Henkel A, Schmachtel S, Sönnichsen C. Single unlabeled protein detection on individual plasmonic nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2012;12(2):1092–1095. doi: 10.1021/nl204496g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorgenfrei S, et al. Label-free single-molecule detection of DNA-hybridization kinetics with a carbon nanotube field-effect transistor. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6(2):126–132. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heller DA, et al. Multimodal optical sensing and analyte specificity using single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4(2):114–120. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li JF, et al. Shell-isolated nanoparticle-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nature. 2010;464(7287):392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsumoto K, Subramanian S, Murugesan R, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC. Spatially resolved biologic information from in vivo EPRI, OMRI, and MRI. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9(8):1125–1141. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borbat PP, Costa-Filho AJ, Earle KA, Moscicki JK, Freed JH. Electron spin resonance in studies of membranes and proteins. Science. 2001;291(5502):266–269. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5502.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blank A, Dunnam CR, Borbat PP, Freed JH. Pulsed three-dimensional electron spin resonance microscopy. Appl Phys Lett. 2004;85(22):5430–5432. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rugar D, Budakian R, Mamin HJ, Chui BW. Single spin detection by magnetic resonance force microscopy. Nature. 2004;430(6997):329–332. doi: 10.1038/nature02658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mamin HJ, Poggio M, Degen CL, Rugar D. Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging with 90-nm resolution. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2(5):301–306. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Degen CL, Poggio M, Mamin HJ, Rettner CT, Rugar D. Nanoscale magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(5):1313–1317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812068106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu CC, et al. Characterization and application of single fluorescent nanodiamonds as cellular biomarkers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(3):727–732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605409104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neugart F, et al. Dynamics of diamond nanoparticles in solution and cells. Nano Lett. 2007;7(12):3588–3591. doi: 10.1021/nl0716303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang YR, et al. Mass production and dynamic imaging of fluorescent nanodiamonds. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3(5):284–288. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gruber A, et al. Scanning confocal optical microscopy and magnetic resonance on single defect centers. Science. 1997;276(5321):2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balasubramanian G, et al. Nanoscale imaging magnetometry with diamond spins under ambient conditions. Nature. 2008;455(7213):648–651. doi: 10.1038/nature07278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maze JR, et al. Nanoscale magnetic sensing with an individual electronic spin in diamond. Nature. 2008;455(7213):644–647. doi: 10.1038/nature07279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balasubramanian G, et al. Ultralong spin coherence time in isotopically engineered diamond. Nat Mater. 2009;8(5):383–387. doi: 10.1038/nmat2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maletinsky P, et al. A robust scanning diamond sensor for nanoscale imaging with single nitrogen-vacancy centres. Nat Nanotechnol. 2012;7(5):320–324. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinert S, et al. High sensitivity magnetic imaging using an array of spins in diamond. Rev Sci Instrum. 2010;81(4):043705. doi: 10.1063/1.3385689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pham LM, et al. Magnetic field imaging with nitrogen-vacancy ensembles. New J Phys. 2011;13(4):045021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Acosta VM, et al. Broadband magnetometry by infrared-absorption detection of nitrogen-vacancy ensembles in diamond. Appl Phys Lett. 2010;97(17):174104–174103. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole JH, Hollenberg LCL. Scanning quantum decoherence microscopy. Nanotechnology. 2009;20(49):495401. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/49/495401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall LT, Cole JH, Hill CD, Hollenberg LCL. Sensing of fluctuating nanoscale magnetic fields using nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;103(22):220802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.220802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall LT, et al. Monitoring ion-channel function in real time through quantum decoherence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(44):18777–18782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002562107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinert S, et al. 2013. Magnetic spin imaging under ambient conditions with sub-cellular resolution. Nature Communications 4:1607.

- 27.McGuinness LP, et al. Quantum measurement and orientation tracking of fluorescent nanodiamonds inside living cells. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6(6):358–363. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grotz B, et al. Sensing external spins with nitrogen-vacancy diamond. New J Phys. 2011;13(5):055004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGuinness LP, et al. 2012. Ambient nanoscale sensing with single spins using quantum decoherence. arXiv:1211.5749.

- 30.Mamin HJ, Sherwood MH, Rugar D. 2012. Detecting external electron spins using nitrogen-vacancy centers. Physical Review B 6(19):195422.

- 31.Grinolds MS, et al. Nanoscale magnetic imaging of a single electron spin under ambient conditions. Nature Physics. 2013;9(4):215–219. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mamin HJ, et al. Nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance with a nitrogen-vacancy spin sensor. Science. 2013;339(6119):557–560. doi: 10.1126/science.1231540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staudacher T, et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy on a (5-Nanometer)3 sample volume. Science. 2013;339(6119):561–563. doi: 10.1126/science.1231675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McConnell HM, Watts TH, Weis RM, Brian AA. Supported planar membranes in studies of cell-cell recognition in the immune system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;864(1):95–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(86)90016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bertini I, et al. Persistent contrast enhancement by sterically stabilized paramagnetic liposomes in murine melanoma. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(3):669–672. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradac C, et al. Observation and control of blinking nitrogen-vacancy centres in discrete nanodiamonds. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5(5):345–349. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossetti FF, Bally M, Michel R, Textor M, Reviakine I. Interactions between titanium dioxide and phosphatidyl serine-containing liposomes: Formation and patterning of supported phospholipid bilayers on the surface of a medically relevant material. Langmuir. 2005;21(14):6443–6450. doi: 10.1021/la0509100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.