Abstract

Background

Cysteinyl leukotrienes contribute to asthma pathogenesis, in part through CysLT1 receptor (CysLT1R). Recently discovered lineage-negative type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) potently produce IL-5 and IL-13.

Objectives

We hypothesized that lung ILC2 may be activated by leukotrienes through CysLT1R.

Methods

ILC2 (Thy 1.2+ lineage-negative lymphocytes) and CysLT1R were detected in the lungs of WT, STAT6−/−, and RAG2−/− mice by flow cytometry. Levels of Th2 cytokines were measured in purified lung ILC2 stimulated with leukotriene D4 (LTD4) in the presence or absence of the CysLT1R antagonist montelukast. Calcium influx was measured by Fluo-4 intensity. Intranasal LTD4 and LTE4 were administered to naive mice and levels of ILC2 IL-5 production determined. Finally, LTD4 was co-administered with Alternaria repetitively to RAG2−/− mice (have ILC2) and IL-7R−/− mice (lack ILC2) and total ILC2 numbers, proliferation (Ki-67+) and BAL eosinophils measured.

Results

CysLT1R was expressed on lung ILC2 from WT, RAG2−/−, and STAT6−/−naïve and Alternaria-challenged mice. In vitro, LTD4 induced ILC2 to rapidly generate high levels of IL-5 and IL-13 within six hours of stimulation. Interestingly, LTD4, but not IL-33, induced high levels of IL-4 by ILC2. LTD4 administered in-vivo rapidly induced ILC2 IL-5 production that was significantly reduced by montelukast pre-treatment. Finally, LTD4 potentiated Alternaria-induced eosinophilia as well as ILC2 accumulation and proliferation.

Conclusions

We present novel data that CysLT1R is expressed on ILC2 and LTD4 potently induces CysLT1R-dependent ILC2 production of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. Additionally, LTD4 potentiates Alternaria-induced eosinophilia and ILC2 proliferation and accumulation.

Keywords: Asthma, Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells, Cysteinyl Leukotrienes, CysLT1R

Introduction

Type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) have recently been discovered and encompass the originally named natural helper cells, nuocytes, and innate type 2 helper cells1–4. ILC2 do not express known lineage markers (lineage-negative) and produce large amounts of IL-5 and IL-13 in response to cytokines IL-33 and/or IL-251–3. In mice, studies have demonstrated the presence of ILC2 in the gastro-intestinal tract, mesenteric fat and lymph nodes, spleen, liver, bone marrow and lung1–3, 5–8, while studies in humans have detected ILC2 in GI tract, lung, BAL, and nasal polyps7, 9. Importantly, ILC2 have been shown to contribute to airway hyperresponsiveness and type-2 lung inflammatory responses in mice infected with influenza virus and after challenge with multiple allergens including Alternaria, papain, house dust mite and OVA8, 10–14. Thus, these reports suggest a role for ILC2 in asthma pathogenesis.

In addition to Th2 cytokines, cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs) play an established role as mediators in human asthma15–18 as well as contribute to lung inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness and airway remodeling in mice19–22. CysLTs are lipid mediators derived from arachidonic acid and are generated by mast cells, eosinophils, macrophages and dendritic cells23. Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 (CysLT1R) is the high-affinity receptor for leukotriene D4 (LTD4) and is expressed on structural cells such as airway smooth muscle cells as well as immune cells including eosinophils, mast cells, macrophages and dendritic cells24–26. There is over 80% sequence homology between human and mouse CysLT1R allowing for studies to be performed in mice utilizing pharmacologic blockade with CysLT1R antagonists such as montelukast20, 21.

Th2 cytokines including IL-4 and IL-13 have been shown to upregulate CysLT1R on various cell types in humans and direct IL-13 administration to airways of mice increases CysLTs26–28. Further, human Th2 cells were recently shown to selectively express CysLT1R when compared with Th1 cells, and stimulation of Th2 cells with cysteinyl leukotrienes induced calcium influx, chemotaxis and IL-13 production that was dependent on CysLT1R29, 30. Collectively, these reports strongly suggest that Th2 cytokines and CysLTs/CysLT1R regulate each other reciprocally. Evidence is mounting that ILC2, similar to Th2 cells, may contribute significantly to type 2 lung inflammation and hyperresponsiveness through IL-5 and IL-13 production8, 10–14, and we hypothesized that ILC2 may be activated by CysLTs and promote cytokine production or proliferative responses.

Previous studies have demonstrated that IL-33 and/or IL-25 are the primary inducers of ILC2 expansion and cytokine production1–3. These reports utilized reporter mice stimulated with IL-25 or IL-33 to identify ILC2 populations and further showed that in-vitro stimulation of purified ILC2 with IL-25 and/or IL-33 led to dramatic increases in IL-5 and IL-13 production, but very little IL-41–3, 31. More recently, a report showed that ILC2 obtained from human nasal polyp tissue stimulated with thymic stromal lymphopoeitin (TSLP) led to induction of Th2 cytokine production including IL-432. Apart from IL-33, IL-25, and possibly TSLP, additional mediators that regulate ILC2 cytokine production and expansion are not known and may be important in asthma pathogenesis.

Here we report the novel findings that CysLT1R is expressed on lung ILC2 in mice and that LTD4 potently induces CysLT1R-dependent ILC2 production of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. Additionally, LTD4 potentiates Alternaria-induced eosinophilia and ILC2 proliferation and accumulation. Thus, these studies are the first to provide a link between type 2 innate lymphoid cell responses and leukotriene mediators known to contribute to asthma pathogenesis.

Methods

Mice, airway challenges and pharmacologic interventions

Six to eight week old male and female WT C57BL/6, RAG2−/−, IL-7R−/−, and STAT6−/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and bred in-house. Mice were challenged with either a single intranasal dose (25 µg or 100 µg) of Alternaria alternata extract (lot nos. 177372 and 161037) and euthanized 12 hrs, 24 hrs, or 3 days later or received four challenges over 10 days as we have previously reported14. In some experiments, naïve WT mice received intranasal LTC4, LTD4 or LTE4 (100 ng in 2.5% ethanol, Cayman Chemical) and were euthanized three hours later. Mice were treated with intragastric montelukast (0.2 mg in 1% DMSO, Cayman Chemical) or 1% DMSO in PBS given daily for three days prior to LTD4 or LTE4 challenge. In other experiments, RAG2−/− mice received intranasal Alternaria (25ug) with or without LTD4 (100ng, Cayman chemical). All studies were approved by the University of California San Diego Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Lung and bone marrow processing

BAL fluid was obtained by intratracheal insertion of a catheter and five lavages with 0.7 mL 2% BSA (Sigma)14. Lungs were placed in RPMI and single cell suspensions were obtained using a gentleMACS dissociator (Miltenyi) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Live total BAL and lung cells were counted using a flow cytometer (Accuri C6, BD Biosciences). Bone marrow was isolated from both tibias and fibulas as we have previously described33.

Flow Cytometry

Lung single-cell suspensions or BAL cells were first incubated with a monoclonal antibody to CD16/CD32 (24G.2) for 10 min to block Fc receptors. BAL cells were stained with PerCP-conjugated CD45.2, PE-conjugated Siglec-F, APC-conjugated Gr-1, and FITC-conjugated CD11c (eBioscience). BAL eosinophils were identified as Siglec F-positive CD11c-negative cells. To identify lung ILC2, lung cells were stained with PerCP-conjugated CD45.2 (eBioscience) and lineage staining was performed only with FITC antibodies that included FITC-conjugated lineage cocktail (Biolegend), CD11c (eBioscience), NK1.1 (eBioscience), CD4 (eBioscience), CD5 (BD Biosciences), CD8 (BD Bioscience), FcεR1 (Biolegend), TCRβ (BD Bioscience), TCRγδ (Biolegend), and CD19 (Biolegend). Lung cells were also stained with APC-conjugated Thy1.2 (eBioscience) and ILC2s were identified as lineage-negative Thy1.2-positive lymphocytes14. Lung Th2 and non-Th2 cells were identified by T1/ST2-positive (MD biosciences) or negative CD4+ lymphocytes, respectively. To identify ILC2 CysLT1R expression, lung cells were stained with polyclonal rabbit to the C-terminus portion of CysLT1R (Cayman Chemical) after permeabilization or with polyclonal rabbit to the EC3 extracellular portion of CysLT1 R34 (clone RB34, kindly provided by Dr. Joshua Boyce, Harvard, Boston) without permeabilization followed by PE conjugated F(ab′)2 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (eBioscience). In some experiments, CysLT1R blocking peptide (Cayman Chemical) and C-terminus CysLT1R Ab in 10:1 ratio were incubated for three hours prior to staining of lung cells by permeabilized methods. Intracellular IL-5 staining was performed after 104 lung cells per well were incubated in a 96-well plate for 16–18 hours with 10 ng/mL IL-2 (R&D Systems), 10 ng/mL IL-7 (R&D Systems), and Golgi-Plug (BD Biosciences) followed by fixation and permeablization (BD Biosciences) and staining with PE-conjugated IL-5 or isotype control (eBioscience). Ki-67 staining was performed using a FoxP3 staining kit (eBioscience) followed by APC-conjugated Ki-67 (eBioscience)14. Flow cytometry was performed with an Accuri C6 cytometer (BD Biosciences) and sample data were further analyzed with Flow Jo software (Tree Star).

ILC2 Cell Sorting and Culture

WT mice received three or four 25µg intranasal Altemaria challenges over 9–10 days prior to FACS sorting in order to expand ILC2. Sorting of ILC2 (CD45+ lineage-negative Thy1.2 positive lymphocytes) was performed using a FACS Aria cell sorter (BD Biosciences). Purified ILC2 (>99%) were rested for 40 hours in 10ng/mL IL-2 and IL-7 (R&D Systems) in a 96-well flat bottom plate (40,000 cells per well). Prior to stimulation, the media was changed and ILC2 were cultured for six hours with IL-33 (30ng/ml, R&D Systems) or LTD4 (10−6 M or 10−8 M in 0.5% ethanol, Cayman). In some wells, ILC2 were pre-treated with 1 µM montelukast in 0.5% ethanol (Cayman) for two hours prior to stimulation with LTD4. After six hours of stimulation, supernatants were collected for cytokine analysis by ELISA.

Calcium signaling

Purified ILC2s were cultured with 10 ng/mL each of IL-2 and IL-7 and rested for at least 3 days prior to calcium signaling experiments. Calcium signaling was detected with a Fluo-4 Direct Calcium Assay Kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Calcium influx was recorded in the FL2 channel of an Accuri C4 flow cytometer as previously reported35 and 10−6 M LTD4 was added after 60 seconds of recording. In some experiments, ILC2s were incubated at 37°C with 1 µm Montelukast prior to performing calcium tracer studies.

ELISA for BAL cytokines and CysLT1R

ELISA of cell culture supernatants for IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 (all R&D Systems) and BAL CysLT Enzyme Immunoassay (Cayman Chemical) were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and read with a microplate reader (model 680, Bio-Rad).

RT and real-time PCR

FACS sorted lung ILC2, CD4+ T1ST2+ and CD4+ T1ST2- cells were lysed using TRIzol (Life technologies) to isolate RNA. An aliquot of total RNA (0.5 µg) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Roche) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Diluted cDNA was subject to real-time PCR using SYBR Green I master (Roche) and the RT-PCR–specific primers. The oligonucleotide primer sequences were as follows: CysLT1R forward, 5′-CAACGAACTATCCACCTTCACC-3′ and CysLT1R reverse, 5′- AGCCTTCTCCTAAAGTTTCCAC-3′; L32 forward, 5′-GAA ACT GGC GGA AAC CCA-3′; L32 reverse, 5′-GGA TCT GGC CCT TGA ACC TT-3′. Data are presented as normalized to housekeeping gene L32 using Roche LightCycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics, Germany).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software. Mann-Whitney test or unpaired t-test was used where indicated. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

CysLT1R is expressed on lung and bone marrow ILC2

We have previously reported the presence of type 2 innate lymphoid cells in the lungs of mice defined as CD45+ lineage-negative Thy1.2 positive lymphocytes14. ILC2 lack surface marker expression of CD3, CD4, CD8, TCRβ, TCRβ, CD5, CD19, B220, NK1.1, Ter119, Gr-1, CD11c and FcεR11–3. This combination excludes B, T, NK, and NKT cells as well as mast cells, basophils, granulocytes, dendritic cells and macrophages. Lung ILC2 express T1/ST2 (IL-33R), Sca-1, c-kit, IL-7R, Thy 1.2, CD25, and CD4414 and have a phenotype most consistent with previously described natural helper cells1. We will now refer to these cells as type 2 innate lymphoid cells as is standard convention based on consensus4.

To determine whether ILC2 express the cysteinyl leukotriene 1 receptor, CysLT1R, we stained single cell suspensions from the lungs of naïve WT mice for FACS analysis. We used both permeabilized and non-permeablized protocols for staining as CysLT1R can be expressed both on the cell surface as well as nuclear membrane34. Lineage-negative Thy1.2 positive lymphocytes showed strong CysLT1R expression with permeabilization using the C-terminus antibody (Fig 1A). To determine whether the CysLT1R antibody we used was specific for CysLT1R, we incubated some samples with CysLT1R specific blocking peptide (amino acids 318–337). Samples incubated with CysLT1R blocking peptide had complete abrogation of CysLT1R staining demonstrating antibody specificity for CysLT1R. To confirm the presence of CysLT1R on ILC2, we also performed staining with an antibody specific to the extracellular EC3 region (RB34) of CysLT1R in the absence of permeabilization34 (Fig 1B). Staining with the RB34 antibody further demonstrated expression of CysLT1R on ILC2. Additionally, we assessed the levels of CyLT1R mRNA by qPCR in FACS purified ILC2 from the lungs of Alternaria-challenged mice compared with levels from sorted lung Th2 cells (CD4+T1/ST2+) and non-Th2 cells (CD4+T1/ST2-). We detected increased CysLT1R mRNA levels in ILC2 compared to Th2 cells, known to express CysLT1R36, and very little expression in non-Th2 cells (Fig 1C). To determine if CysLT1R was expressed on bone marrow ILC2, we performed similar staining with bone marrow from naïve mice (Fig 1D) and found that ILC2 in the bone marrow express CysLT1R similar to lung ILC2. Thus, lung and bone marrow ILC2 from WT naïve mice express CysLT1R suggesting that ILC2 may be primed to respond to cysteinyl leukotrienes.

Figure 1. CysLT1R is expressed on lung and bone marrow type 2 innate lymphoid cells.

Single cell suspensions from lungs of naïve mice were stained with CD45, lineage (CD3, CD4, CD5, CD8, CD19, Gr-1, CD11b, CD11c, B220, Ter-119, NK1.1, FcεR1, TCRβ, and TCRγδ), and Thy1.2. ILC2 gated on CD45+ lineage-negative Thy1.2+ lymphocytes (A, left). Cells were then stained with a C-terminus antibody for CysLTR1 with and without blocking peptide using permeabilized methods (A, right). (B) ILC2 from naïve WT mice were stained with an antibody to the extracellular portion of CysLT1R (RB34) using non-permeabilized methods. (C) CysLT1R mRNA levels from FACS purifed lung ILC2, CD4+T1/ST2+, and CD4+T1/ST2- cells from WT mice receiving 4 challenges with Alternaria. Data shown from triplicate samples, p < 0.05, Mann-whitney. (D) Bone marrow was taken from naïve WT mice and processed for FACS analysis of ILC2 CysLT1R expression using the RB34 antibody. (E) Lung ILC2 CysLT1R expression from WT and STAT6−/− mice and (F) from RAG2−/− mice after staining with the RB34 antibody. Plots representative of at least two independent experiments, control antibody staining in solid grey.

CysLT1R is expressed on lung ILC2 independent of STAT6 and RAG2

Previous reports have suggested that IL-4 and IL-13 can upregulate CysLT1R expression on different cell types27, 37. As downstream IL-4 and IL-13 signaling is primarily mediated through signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6)38, we sought to determine whether STAT6 was required for ILC2 CysLT1R expression. Lung ILC2 from naïve STAT6 deficient (STAT6−/−) mice displayed similar surface levels of CysLT1R compared with ILC2 from WT mice (Fig 1E). RAG2−/− lack B and T cells but have innate lymphoid cell populations including lung ILC21, 7, 8, 14. ILC2 from lungs of RAG2−/− mice displayed expression of CysLT1R (Fig 1F). Thus, lung ILC2 expression of CysLT1R is constitutive and independent of STAT6 or presence of adaptive immune cells.

ILC2 expression of CysLT1R is stable after allergen challenges

We next determined whether ILC2 expression of CysLT1R was further upregulated after mice were challenged with intranasal allergen. We have previously demonstrated that mice receiving a single intranasal challenge with the fungal allergen Alternaria develop innate eosinophilia, increased BAL IL-5 and IL-13, and ILC2 activation14, 33. Lung ILC2 from mice that received one challenge of Alternaria maintained similar CysLT1R expression compared with PBS control challenged mice when measured at 24 hours and 3 days after challenge. ILC2 from mice that received four challenges with Alternaria over 10 days, a protocol that induces a strong adaptive Th2 response and increased IgE14, also had similar CysLT1R expression compared to PBS challenged mice (Fig 2A & B). Additionally, STAT6−/− (Fig 2A) and RAG2−/− (Fig 2B) ILC2 maintained expression of CysLT1R after single and multiple challenges with Alternaria, though we observed slightly decreased expression on ILC2 from RAG2−/−mice compared with WT mice at baseline (Fig 1F), 24 hours and three days after challenge. Overall, this suggests that ILC2 expression of CysLT1R is stable after allergen challenge and is not significantly affected by absence of STAT6 or adaptive immune cells.

Figure 2. ILC2 expression of CysLT1R is stable after allergen challenges and independent of STAT6 or RAG2.

WT, STAT6−/−, and RAG2−/− mice were administered a single intranasal challenge with Alternaria allergen once and lung cells obtained at 24 hours and 3 days or given 4 challenges over 10 days. Single suspensions of lung were stained for ILC2 and surface CysLT1R using the RB34 antibody or control antibody (grey). Histograms gated on lung ILC2 (CD45+ Lineage-negative Thy1.2+ lymphocytes). (A) WT and STAT6−/− ILC2 CysLT1R expression in Alternaria-challenged mice at 24 hours, 3 days, or 10 days. (B) WT and RAG2−/− ILC2 CysLT1R expression in Alternaria-challenged mice at 24 hours, 3 days, or 10 days. Plots representative of two independent experiments at each time point, control antibody staining in solid grey.

Leukotriene D4 potently induces ILC2 Th2 cytokine production through CysLT1R

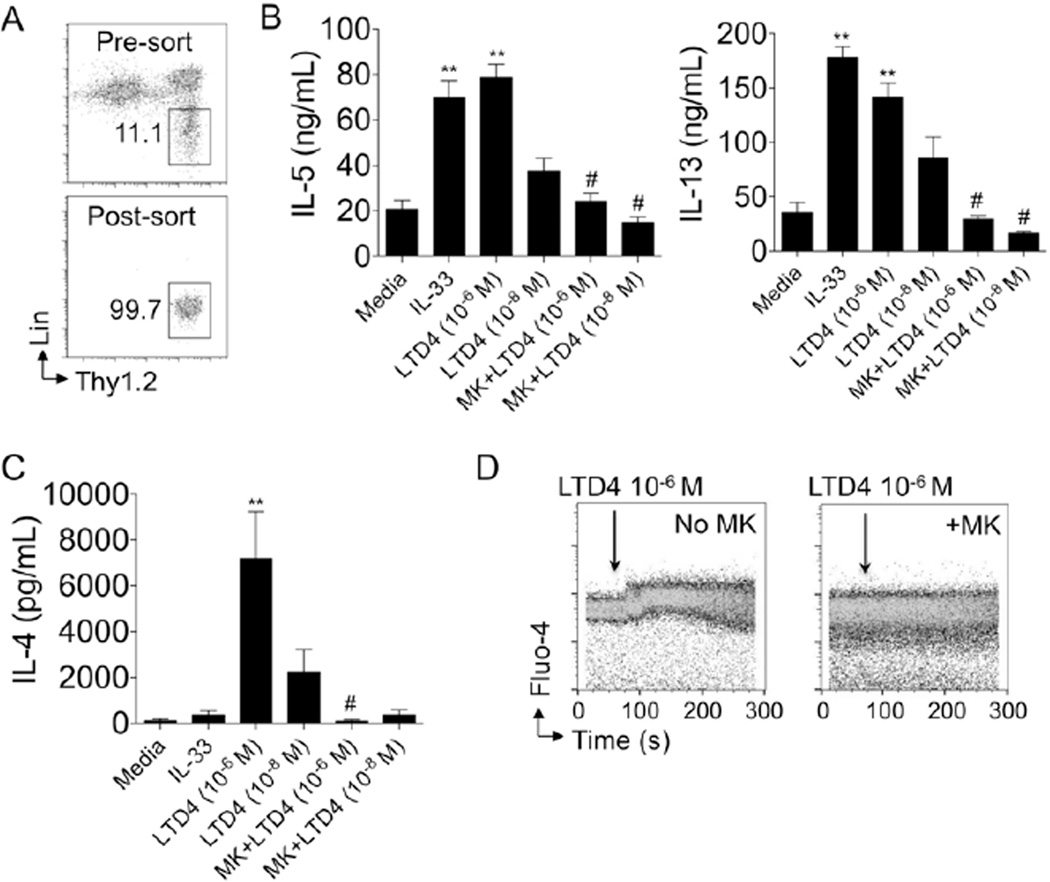

To determine whether cysteinyl leukotrienes can activate lung ILC2, we performed FACS sorting of lung ILC2 from mice that received 3–4 Alternaria intranasal challenges in vivo. Lung ILC2 expand from approximately 10,000 per mouse to over 100,000 per mouse after three to four Alternaria challenges, thus facilitating in vitro studies with a greater number of purified cells. After sorting, we obtained a greater than 99% pure ILC2 population (Fig 3A) and then rested the cells for two days with media changes prior to stimulation studies. Rested ILC2 were cultured with IL-33 and LTD4 with and without the cysLT1R antagonist montelukast for six hours prior to collecting culture supernatant for ELISA. ILC2 stimulated with IL-33 (30ng/ml) produced large amounts of IL-5 and IL-13 (over 60 ng/ml of IL-5 and 150 ng/ml of IL-13, Fig 3B) as previously reported1–3, 31. Interestingly, LTD4 (10−6 M) induced similar levels of IL-5 and only slightly lower levels of IL-13 compared with IL-33. Pre-treatment with montelukast abrogated the LTD4-induced IL-5 and IL-13 production. Previous in vitro studies have shown that ILC2 produce large amounts of IL-5 and IL-13, but very little IL-4 and only after phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) plus ionomycin stimulation1–3, 31. Strikingly, lung ILC2 (40,000 cells/well) stimulated with 10−6 M of LTD4 produced over 6 ng/ml of IL-4 (Fig 3C). In contrast, IL-33-stimulated ILC2 produced no significant increase in IL-4 compared to media as is consistent with previous reports. Further, cells that were cultured for two hours with montelukast before LTD4 stimulation produced very low levels of IL-4 that were comparable to media. Taken together, LTD4 induces a dose-dependent increase in IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 that is mediated by CysLT1R. In contrast to LTD4, the established ILC2 activator IL-33 failed to induce IL-4 production.

Figure 3. Leukotriene D4 induces ILC2 Th2 cytokine production through CysLT1R.

(A) Lung ILC2 were expanded in-vivo after 3 Alternaria challenges followed by FACS sorting and resting for 40 hours prior to in-vitro studies. Pre- (top) and post-sort (bottom) ILC2% shown. (B) IL-5, IL-13 and (C) IL-4 levels determined by ELISA from supernatants of purified ILC2 were stimulated with IL-33, LTD4 (10−6 M and 10−8 M) for 6 hours with and without 1 µM montelukast pre-treatment for 2 hours. (D) ILC2 Fluo-4 intensity over time in seconds after LTD4 10−6 M was added at 60 seconds without montelukast (left) and after pre-treatment with montelukast (right). Data in A & D are representative of two independent experiments and B & C are combined from triplicate wells of each condition of two independent experiments. MK = montelukast. ** P < 0.005 compared to media, # p < 0.01 compared to the same dose of LTD4 alone, Mann-whitney.

CysLT1R is a G protein-coupled receptor that rapidly promotes calcium influx when activated. To determine whether LTD4 could induce ILC2 calcium influx directly, we cultured sorted ILC2 (Fig 3A) from the lungs of mice with the calcium tracer Fluo-4 and used flow cytometry to measure changes in calcium influx35. LTD4 was added to purified ILC2 at 60 seconds and Fluo-4 intensity was measured (Fig 3D). Some ILC2 were pre-treated with the CysLT1R antagonist montelukast. ILC2 that received LTD4 without pre-treatment had a rapid and significant increase in calcium influx after LTD4 was added. In contrast, calcium influx was abrogated in ILC2 that received montelukast prior to the addition of LTD4. Thus, LTD4 directly and rapidly induces lung ILC2 calcium influx dependent on CysLT1R.

CysLTs are rapidly induced by Alternaria challenge in a STAT6 dependent manner

We have previously reported that ILC2 are activated within hours after a single airway exposure to Alternaria, a clinically relevant aeroallergen associated with severe asthma14. To determine whether CysLTs are increased after Alternaria challenge and thus may be available to activate ILC2, we performed ELISA for CysLTs in the BAL of challenged and unchallenged mice. BAL from WT mice showed an increase in CysLTs 12 hours after a single Alternaria challenge compared with PBS challenged mice (Fig 4A). A previous report showed that BAL CysLTs are increased after direct administration of IL-13 to the airways of mice28. As IL-13 downstream signaling occurs through STAT6, we assessed levels of BAL CysLTs in STAT6−/− mice after Alternaria challenge. Impressively, the increased BAL level of CysLTs in WT mice was completely abrogated in STAT6−/− mice receiving Alternaria challenge. Thus, rapid production of CysLTs occurs in the airway after exposure to a clinically relevant allergen, and is dependent on STAT6.

Figure 4. STAT6 dependent CysLTs are induced by Alternaria and promote ILC2 IL-5 production in vivo.

(A) BAL CysLTs measured from naïve WT and STAT6−/− mice 12 hours after a single intranasal challenge with 100 mg of Alternaria. 9 mice/group Alternaria challenged, 3 mice per group PBS, Mann-whitney,**P < 0.005. (B) WT naïve mice received a single intranasal challenge with LTC4, LTD4, LTE4, or PBS and some mice were administered three doses of intragastric montelukast before challenges. Lung cells obtained three hours after challenge were cultured overnight with protein transport inhibitor and stained for ILC2 intracellular IL-5. Lung ILC2 (left) were gated and intracellular IL-5 from mice receiving LTC4, LTD4 and LTD4 with (bottom row) and without montelukast (top row). Control antibody staining and ILC2 IL-5 from mice receiving PBS challenge as shown. MK = montelukast. Data shown is representative of 2–3 independent experiments.

LTD4 increases IL-5 producing ILC2 in-vivo dependent on CysLT1R

To determine whether LTD4 can activate ILC2 in vivo, we administered a single intranasal challenge of LTD4 to WT mice and performed FACS analysis for ILC2 intracellular IL-5 (Fig 4B). Single cell lung suspensions were obtained 3 hours after LTC4, LTD4 or LTE4 challenge and cultured overnight with a protein transport inhibitor and stained for ILC2 intracellular IL-5 the following day. Some groups of mice received three daily doses of montelukast by oral gavage before LTC4, LTD4 or LTE4 challenge. Mice receiving LTC4, LTD4 or LTE4 had a significantly increased percentage of IL-5 producing ILC2 (21.6, 30.2 and 22.0%, respectively) compared with PBS challenged mice (10.6%). Mice receiving montelukast prior to LTC4 and LTD4 administration had significantly reduced IL-5 producing ILC2 (13.2% and 11.8%, respectively) compared with LTC4 or LTD4 alone. However, montelukast pre-treatment did not significantly affect the percent of LTE4-induced IL-5-producing ILC2 (20.0%). Thus, all three cysteinyl leukotrienes induce IL-5 production by lung ILC2 in-vivo though only LTC4 and LTD4-induced IL-5 production was inhibited by an antagonist of CysLT1R.

LTD4 potentiates Alternaria-induced eosinophilia and ILC2 accumulation and proliferation

To investigate whether LTD4 has a potentiating effect on ILC2 during repetitive allergen challenges, we administered four intranasal challenges of Alternaria alone or with LTD4 to RAG2−/− and IL-7R−/− mice. RAG2−/− mice possess lung ILC2 (Fig 5 A) but lack B and T cells and allowed for determination of LTD4s effects on innate non-B non-T cell populations. In contrast, IL-7R−/− mice lack ILC2 (Fig 5A) and have severely reduced B and T compartments. RAG2−/− mice that received four intranasal challenges with Alternaria have increased percent of ILC2 compared with naïve RAG2−/− mice (Fig 5A). Further, mice that received LTD4 and Alternaria had an increased percent (Fig 5A) and approximately three-fold increase in total numbers of lung ILC2 (Fig 5B) compared with mice that received Alternaria only. We have previously reported that lung ILC2 proliferate, as identified by Ki-67+ staining, and accumulate in the lung after mice are exposed to Alternaria14. Thus, we assessed whether LTD4 increased the proliferation of lung ILC2 and detected significantly increased numbers and percent of Ki-67+ ILC2 in mice receiving Alternaria and LTD4 compared with mice receiving Alternaria only (Fig 5B). We then determined numbers of IL-5 producing ILC2 in the lungs of both groups of mice and found increased IL-5+ ILC2 in mice administered Alternaria and LTD4 compared with mice given Alternaria only (Fig 5C). We also assessed levels of BAL eosinophils in both RAG2−/− mice and IL-7R−/− and detected increased eosinophils in mice receiving LTD4 in RAG2−/− mice (Fig 5C). In contrast, IL-7R−/− mice that do not have ILC2 failed to mount an eosinophilia after administration of Alternaria with or without LTD4. These studies demonstrate that LTD4 potentiates lung ILC2 proliferation, accumulation as well as airway eosinophilia independent of adaptive immunity.

Figure 5. LTD4 induces accumulation and proliferation of lung ILC2 and potentiates Alternaria-induced eosinophilia.

RAG2−/− and IL-7R−/− mice received 4 intranasal challenges with Alternaria alone or with LTD4. (A) Representative FACS plots of ILC2 % from pooled lungs of naïve RAG2−/− (left) and IL-7R−/− mice (middle left) and RAG2−/− mice after 4 challenges with Alternaria alone (middle right) or with LTD4 (right). (B) Total ILC2 per mouse (left), Ki-67+ ILC2 (middle) and percent Ki-67% ILC2 in mice receiving Alternaria alone or with LTD4 (right). (C) Total IL-5+ lung ILC2 (top) from RAG2−/− mice and BAL eosinophils (bottom) from RAG2−/− and IL-7R−/− mice receiving 4 intranasal challenges with Alternaria alone or with LTD4. Total ILC2, Ki-67, and IL-5 ILC2/mouse are from two independent experiments with pooled lungs from 2 mice per group (t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005). BAL eosinophils from 8 mice per group (Mann-whitney,*P < 0.05).

Discussion

Our studies demonstrate several novel findings. First, we show that CysLT1R is expressed on lung and bone marrow ILC2 in unchallenged mice and remains expressed on lung ILC2 after allergen challenges independent of STAT6 and B and T cells. Second, stimulation of purified ILC2 with leukotriene D4, the dominant ligand of CysLT1R, results in robust IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 production dependent on CysLT1R. Third, LTD4 administered to airways of mice regulates ILC2 IL-5 production, proliferation, and potentiates allergen-induced airway eosinophilia independent of adaptive immunity. Our results have significant potential implications for type-2 diseases including allergic asthma where CysLTs are increased and available to potentially activate lung ILC2.

We demonstrated that CysLT1R is expressed on lung ILC2 constitutively and remains expressed after Alternaria challenges. CysLT1R has been detected on immune cells in the airways of human asthmatics compared with normal controls and increases during severe asthma exacerbations39. CysLT1R has also been found to be upregulated after administration of IL-13 to the airways of mice and on various human cell types in-vitro after IL-4, IL-5, or IL-13 stimulation26, 27, 40–42. We have previously found that mice exposed to the fungal allergen Alternaria develop rapid increases in airway IL-5 and IL-1314, though we did not detect an increase in ILC2 CysLT1R expression levels at several time points after Alternaria challenge compared to ILC2 in naïve mice, even in the absence of STAT6. In contrast, we found that STAT6 regulated the induction of CysLTs in airway after Alternaria challenge despite not affecting the level of ILC2 CysLT1R expression. Thus, ILC2 CysLT1R expression is constitutive and stable suggesting that ILC2 are primed to respond to CysLTs that are found at elevated levels in the asthmatic airway.

We found that LTD4 strongly induces purified lung ILC2 to produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. Previously, ILC2 have been shown to produce large amounts of IL-5 and IL-13, but very little, if any, IL-41–3, 31. In these reports, IL-33 was used to stimulate ILC2 and we obtained similar results after purified lung ILC2 were cultured with IL-33. The finding that IL-33 induces IL-5 and IL-13, but not IL-4, may not be specific to ILC2 as a previous report demonstrated that conventional CD4+ T cells stimulated with IL-33 differentiate into IL-5 and IL-13, but not IL-4, producing cells43. The IL-33-induced Th2 differentiation was dependent on known IL-33R signaling molecules p38 and MyD8844. Further, mouse ILC2 have been shown to produce IL-4 after stimulation with PMA and ionomycin1 and when human ILC2 were stimulated with TSLP32. Taken together, this suggests that ILC2 have the capacity to produce a significant amount of IL-4 and the lack of IL-4 production from ILC2 in previous studies may be more related to the downstream effects of IL-33 on lymphocytes. Consistent with our findings that LTD4 stimulates ILC2 Th2 cytokine production, cysteinyl leukotrienes have been previously shown to induce IL-4 production from eosinophils45 and Th2 cells29 as well as IL-5 from mast cells46, 47.

Our results demonstrate that administration of LTC4, LTD4 or LTE4 in-vivo induces ILC2 IL-5 production and montelukast pretreatment inhibited the IL-5 production induced by LTC4 and LTD4, but not LTE4. A few possibilities may explain these findings. LTC4 might directly bind to ILC2 CysLT1R or undergo conversion in-vivo to LTD4 resulting in higher affinity binding to CysLT1R. In contrast, LTE4 may bind to a receptor other than CysLT1R on ILC2 to induce IL-5 production. Consistent with this, one report demonstrated that LTE4-potentiated airway inflammation was dependent on the purinergic receptor P2Y12, but not CysLT1R or CysLT2R48, in an adaptive immune model using OVA as the antigen. Thus, it is interesting to speculate that there may be several receptors on ILC2 that bind leukotrienes and potentially regulate ILC2 cytokine production and proliferation.

We detected increased accumulation and proliferation of ILC2 in the lung when LTD4 was repetitively administered along with Alternaria to RAG2−/− mice. Cysteinyl leukotrienes have been shown in vitro to induce proliferation of mast cells34, 49 and LTE4 has been shown to be more potent than LTD4 in promoting mast cell proliferative responses49, 50. As discussed, LTD4 can be rapidly converted to LTE4 in vivo and it is possible that either or both LTD4 and LTE4 can act directly or indirectly to promote ILC2 proliferation and accumulation48. Additional receptors for cysteinyl leukotrienes independent of cysLT1R and cysLT2R likely exist51 and may help to explain some of our findings once characterized and applied to future ILC2 studies. Interestingly, we administered LTD4 repetitively with and without Alternaria to WT mice (not shown) and found very little effect on LTD4-induced ILC2 proliferation. WT mice administered repetitive Alternaria challenges alone develop a very strong adaptive Th2 response as well as robust ILC2 proliferation that may not be further enhanced by exogenous LTD4. Further, ILC2 proliferation may not be sufficiently induced by LTD4 alone in-vivo and likely requires other signals present during allergen challenge. Finally, though our results suggest that ILC2 accumulate in the lung through local proliferation (Ki-67+ cells), we cannot exclude that LTD4 may promote chemotaxis of ILC2 as previously reported with CD34+ progenitor cells52.

In summary, we present novel findings that ILC2, a recently discovered population of cells that includes natural helper cells and nuocytes1, 2, can be activated by leukotriene D4 to rapidly produce large amounts of Th2 cytokines in a CysLT1R dependent manner. If such findings can be translated to humans, a leukotriene-ILC2 pathway may promote tissue eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness in diseases such as asthma and aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease in which CysLTs are increased.

Key Messages.

Lung Type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) express CysLT1 receptor.

Leukotriene D4 rapidly and robustly induces lung ILC2 calcium influx and IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 production in a CysLT1R-dependent manner.

Leukotriene D4 potentiates Alternaria-induced ILC2 accumulation, proliferation and airway eosinophilia.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Joshua Boyce (Harvard) for kindly providing the RB34 CysLT1R antibody and Dr. Nora Barrett (Harvard) for the staining protocol. We also appreciate the assistance of Cheryl Kim and Anthony Jose at the flow cytometry core at The La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology with cell sorting.

Grant support: NIH grant 1K08AI080938-01A1, NIH U19 Opportunity Fund Award, ALA/AAAI Allergic Respiratory Diseases Award to T.A.D. and AI 38425, AI 70535, AI 72115 to D.H.B.

Abbreviations

- APC

Allophycocyanin

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- CysLT1R

Cysteinyl leukotriene 1 receptor

- FITC

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- LTD4

Leukotriene D4

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PE

Phycoerythrin

- PerCP

Peridinin-chlorophyll-protein complex

- PMA

Phorbol myristate acetate

- RAG2

recombination activating gene 2

- STAT6

signal transducer and activator of transcription 6

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Moro K, Yamada T, Tanabe M, Takeuchi T, Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, et al. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature. 2010;463:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TK, et al. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367–1370. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Price AE, Liang HE, Sullivan BM, Reinhardt RL, Eisley CJ, Erle DJ, et al. Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11489–11494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003988107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spits H, Artis D, Colonna M, Diefenbach A, Di Santo JP, Eberl G, et al. Innate lymphoid cells--a proposal for uniform nomenclature. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:145–149. doi: 10.1038/nri3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brickshawana A, Shapiro VS, Kita H, Pease LR. Lineage-Sca1+c-Kit-CD25+ Cells Are IL-33-Responsive Type 2 Innate Cells in the Mouse Bone Marrow. J Immunol. 2011;187:5795–5804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Q, Saenz SA, Zlotoff DA, Artis D, Bhandoola A. Cutting edge: natural helper cells derive from lymphoid progenitors. J Immunol. 2011;187:5505–5509. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Abt MC, Alenghat T, Ziegler CG, Doering TA, et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1045–1054. doi: 10.1031/ni.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang YJ, Kim HY, Albacker LA, Baumgarth N, McKenzie AN, Smith DE, et al. Innate lymphoid cells mediate influenza-induced airway hyper-reactivity independently of adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:631–638. doi: 10.1038/ni.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mjosberg JM, Trifari S, Crellin NK, Peters CP, van Drunen CM, Piet B, et al. Human IL-25- and IL-33-responsive type 2 innate lymphoid cells are defined by expression of CRTH2 and CD161. Nat Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ni.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halim TY, Krauss RH, Sun AC, Takei F. Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity. 2012;36:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartemes KR, Iijima K, Kobayashi T, Kephart GM, McKenzie AN, Kita H. IL-33-responsive lineage- CD25+ CD44(hi) lymphoid cells mediate innate type 2 immunity and allergic inflammation in the lungs. J Immunol. 2012;188:1503–1513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barlow JL, Bellosi A, Hardman CS, Drynan LF, Wong SH, Cruickshank JP, et al. Innate IL-13-producing nuocytes arise during allergic lung inflammation and contribute to airways hyperreactivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.041. e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein Wolterink RG, Kleinjan A, van Nimwegen M, Bergen I, de Bruijn M, Levani Y, et al. Pulmonary innate lymphoid cells are major producers of IL-5 and IL-13 in murine models of allergic asthma. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1106–1116. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doherty TA, Khorram N, Chang JE, Kim HK, Rosenthal P, Croft M, et al. STAT6 regulates natural helper cell proliferation during lung inflammation initiated by Alternaria. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303:L577–L588. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00174.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters-Golden M, Henderson WR., Jr. Leukotrienes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1841–1854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenzel SE, Larsen GL, Johnston K, Voelkel NF, Westcott JY. Elevated levels of leukotriene C4 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from atopic asthmatics after endobronchial allergen challenge. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:112–119. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu MC, Dube LM, Lancaster J. Acute and chronic effects of a 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor in asthma: a 6-month randomized multicenter trial. Zileuton Study Group. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:859–871. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)80002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korenblat PE. The role of antileukotrienes in the treatment of asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001;86:31–39. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)62309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irvin CG, Tu YP, Sheller JR, Funk CD. 5-Lipoxygenase products are necessary for ovalbumin-induced airway responsiveness in mice. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L1053–L1058. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.6.L1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henderson WR, Jr., Chiang GK, Tien YT, Chi EY. Reversal of allergen-induced airway remodeling by CysLT1 receptor blockade. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:718–728. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200501-088OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson WR, Jr., Tang LO, Chu SJ, Tsao SM, Chiang GK, Jones F, et al. A role for cysteinyl leukotrienes in airway remodeling in a mouse asthma model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:108–116. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.1.2105051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson WR, Jr., Lewis DB, Albert RK, Zhang Y, Lamm WJ, Chiang GK, et al. The importance of leukotrienes in airway inflammation in a mouse model of asthma. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1483–1494. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanaoka Y, Boyce JA. Cysteinyl leukotrienes and their receptors: cellular distribution and function in immune and inflammatory responses. J Immunol. 2004;173:1503–1510. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Figueroa DJ, Breyer RM, Defoe SK, Kargman S, Daugherty BL, Waldburger K, et al. Expression of the cysteinyl leukotriene 1 receptor in normal human lung and peripheral blood leukocytes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:226–233. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parameswaran K, Liang H, Fanat A, Watson R, Snider DP, O'Byrne PM. Role for cysteinyl leukotrienes in allergen-induced change in circulating dendritic cell number in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyce JA. Mast cells and eicosanoid mediators: a system of reciprocal paracrine and autocrine regulation. Immunol Rev. 2007;217:168–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thivierge M, Stankova J, Rola-Pleszczynski M. IL-13 and IL-4 up-regulate cysteinyl leukotriene 1 receptor expression in human monocytes and macrophages. J Immunol. 2001;167:2855–2860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vargaftig BB, Singer M. Leukotrienes mediate murine bronchopulmonary hyperreactivity, inflammation, and part of mucosal metaplasia and tissue injury induced by recombinant murine interleukin-13. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:410–419. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0032OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xue L, Barrow A, Fleming VM, Hunter MG, Ogg G, Klenerman P, et al. Leukotriene E4 activates human Th2 cells for exaggerated proinflammatory cytokine production in response to prostaglandin D2. J Immunol. 2012;188:694–702. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parmentier CN, Fuerst E, McDonald J, Bowen H, Lee TH, Pease JE, et al. Human T(H)2 cells respond to cysteinyl leukotrienes through selective expression of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1136–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koyasu S, Moro K. Innate Th2-type immune responses and the natural helper cell, a newly identified lymphocyte population. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11:109–114. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283448808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mjosberg J, Bernink J, Golebski K, Karrich JJ, Peters CP, Blom B, et al. The Transcription Factor GATA3 Is Essential for the Function of Human Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells. Immunity. 2012;37:649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doherty TA, Khorram N, Sugimoto K, Sheppard D, Rosenthal P, Cho JY, et al. Alternaria Induces STAT6-Dependent Acute Airway Eosinophilia and Epithelial FIZZ1 Expression That Promotes Airway Fibrosis and Epithelial Thickness. J Immunol. 2012;188:2622–2629. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang Y, Borrelli LA, Kanaoka Y, Bacskai BJ, Boyce JA. CysLT2 receptors interact with CysLT1 receptors and down-modulate cysteinyl leukotriene dependent mitogenic responses of mast cells. Blood. 2007;110:3263–3270. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vines A, McBean GJ, Blanco-Fernandez A. A flow-cytometric method for continuous measurement of intracellular Ca(2+) concentration. Cytometry A. 2010;77:1091–1097. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prinz I, Gregoire C, Mollenkopf H, Aguado E, Wang Y, Malissen M, et al. The type 1 cysteinyl leukotriene receptor triggers calcium influx and chemotaxis in mouse alpha beta- and gamma delta effector T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:713–719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamoureux J, Stankova J, Rola-Pleszczynski M. Leukotriene D4 enhances immunoglobulin production in CD40-activated human B lymphocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:924–930. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goenka S, Kaplan MH. Transcriptional regulation by STAT6. Immunol Res. 2011;50:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s12026-011-8205-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu J, Qiu YS, Figueroa DJ, Bandi V, Galczenski H, Hamada K, et al. Localization and upregulation of cysteinyl leukotriene-1 receptor in asthmatic bronchial mucosa. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:531–540. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0124OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chavez J, Young HW, Corry DB, Lieberman MW. Interactions between leukotriene C4 and interleukin 13 signaling pathways in a mouse model of airway disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:440–446. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-440-IBLCAI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thivierge M, Doty M, Johnson J, Stankova J, Rola-Pleszczynski M. IL-5 up-regulates cysteinyl leukotriene 1 receptor expression in HL-60 cells differentiated into eosinophils. J Immunol. 2000;165:5221–5226. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Early SB, Barekzi E, Negri J, Hise K, Borish L, Steinke JW. Concordant modulation of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor expression by IL-4 and IFN-gamma on peripheral immune cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:715–720. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0252OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurowska-Stolarska M, Kewin P, Murphy G, Russo RC, Stolarski B, Garcia CC, et al. IL-33 induces antigen-specific IL-5+ T cells and promotes allergic-induced airway inflammation independent of IL-4. J Immunol. 2008;181:4780–4790. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liew FY, Pitman NI, McInnes IB. Disease-associated functions of IL-33: the new kid in the IL-1 family. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:103–110. doi: 10.1038/nri2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bandeira-Melo C, Hall JC, Penrose JF, Weller PF. Cysteinyl leukotrienes induce IL-4 release from cord blood-derived human eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:975–979. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.124269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mellor EA, Frank N, Soler D, Hodge MR, Lora JM, Austen KF, et al. Expression of the type 2 receptor for cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLT2R) by human mast cells: Functional distinction from CysLT1R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11589–11593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2034927100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mellor EA, Austen KF, Boyce JA. Cysteinyl leukotrienes and uridine diphosphate induce cytokine generation by human mast cells through an interleukin 4-regulated pathway that is inhibited by leukotriene receptor antagonists. J Exp Med. 2002;195:583–592. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paruchuri S, Tashimo H, Feng C, Maekawa A, Xing W, Jiang Y, et al. Leukotriene E4-induced pulmonary inflammation is mediated by the P2Y12 receptor. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2543–2555. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiang Y, Kanaoka Y, Feng C, Nocka K, Rao S, Boyce JA. Cutting edge: Interleukin 4-dependent mast cell proliferation requires autocrine/intracrine cysteinyl leukotriene-induced signaling. J Immunol. 2006;177:2755–2759. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paruchuri S, Jiang Y, Feng C, Francis SA, Plutzky J, Boyce JA. Leukotriene E4 activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and induces prostaglandin D2 generation by human mast cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16477–16487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705822200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Austen KF, Maekawa A, Kanaoka Y, Boyce JA. The leukotriene E4 puzzle: finding the missing pieces and revealing the pathobiologic implications. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.046. quiz 15-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bautz F, Denzlinger C, Kanz L, Mohle R. Chemotaxis and transendothelial migration of CD34(+) hematopoietic progenitor cells induced by the inflammatory mediator leukotriene D4 are mediated by the 7-transmembrane receptor CysLT1. Blood. 2001;97:3433–3440. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]