Abstract

Objectives

To characterize paediatric presentations of stabbing to emergency departments across London and to audit existing referral rates to the police and social services against the new standard set by the General Medical Council.

Design

Retrospective multi-centre service evaluation/audit.

Setting

All emergency departments within London.

Participants

Patients under 18 years of age presenting to emergency departments with non-accidental stabbing between 1 April 2007 and 30 April 2009.

Main outcome measures

Patient age, nature of assault, assailant, injuries and management. Rates of documented referral to police and social services, as mandated by GMC guidance.

Results

A total of 381 presentations were identified from 20 out of the 32 hospitals in London, 160 of whom were less than 16 years old. The majority were seen only by emergency department staff and only a minority (28%) were admitted. Three died in the departments. A knife was the commonest weapon and the limbs the most common site of injury. Referrals to police were documented in only 30% of patients (43% if <16 years old) and to social services in 16% (31% if <16 years old) of those discharged. In the majority, there was no documentation (police 64%, social services 79%).

Conclusions

A significant number of paediatric stabbings present to emergency departments across London. The majority of these are discharged directly from departments. Of those discharged, documentation regarding referral rates to Police and Social Services was poor, and documented referral rates low. This study covered a period prior to the introduction of new General Medical Council guidance and a repeat audit to assess subsequent documented referrals is required.

Introduction

Stabbings of children and young people in London are sadly rarely out of the news and an apparent increase in frequency is of national concern.1,2 There is currently little published data quantifying and exploring the interactions of these patients with emergency departments and hospital services.1,2

Hospital Episode Statistics document only those admitted and so present only the tip of an iceberg of cases. A recent audit by the Helicopter Emergency Medical Service highlighted an increasing frequency of major paediatric trauma related to stabbing; however, it provides little information of minor injuries. The Metropolitan Police, British Crime Survey, Offending, Crime and Justice Survey and the Youth Justice Board Surveys similarly present incomplete aspects of stabbing-related injuries and do not address interactions with, or management by, health services.3–6 Their validity has also been challenged following premature government reporting.3

Past anecdotes have highlighted cases whereby individuals whom initially present to emergency departments having sustained a minor stab wound, go on to be murdered or suffer more significant violent trauma at a later date. Consequently, such initial presentation with a minor stab wound could provide a potential opportunity to identify individuals at further risk of violent injury and instigate interventions aimed at preventing injury and death. Such interventions require non-medical services and the sharing of information with other agencies, notably the Police and Social Services.

In 2009, the General Medical Council issued guidelines mandating the sharing of information on all non-accidental stabbings (adult and paediatric) with the police and also highlighted that ‘Any child or young person under 18 arriving with a gunshot wound or a wound from an attack with a knife, blade or other sharp instrument will raise obvious child protection concerns. You must inform an appropriate person or authority promptly of any such incident’.7 In most cases, this authority will be the local social services. This emphasizes the need to consider such cases as non-accidental injury/child maltreatment. Whilst not traditionally considered as such, these cases are examples of deliberate injury to a child by another individual, adult or child, and as such a clearly documented assessment of risk and appropriate instigation of safeguarding procedures and referrals should form a key aspect of their management.

In 2009, a local audit at the North Middlesex Hospital, a District General Hospital in North London, highlighted the high number of paediatric patients presenting with stab wounds to the emergency department and a low referral rate to the police and social services. Expanding this audit a Pan-London study of stabbing in the under 18 population was initiated with the aims of retrospectively establishing the frequency and nature of under 18s presenting to emergency departments with stab wounds and auditing documented referral rates to the police and social services. Initiated in 2009, this study assesses rates, prior to the introduction of the General Medical Council guidelines and so assesses existing practice against a new standard.

Methods

Each of the 32 emergency departments in London was approached to participate in this study. A trainee was identified to conduct the study in each unit. Patients less than 18 years of age who presented with non-accidental stabbing between 1 April 2007 and 31 April 2009 were identified. Due to the range of computer and coding systems in use across London hospitals, it was left to individual departments to decide how best to identify such cases. Cases of accidental stabbing and deliberate self-harm were excluded.

An anonymized pro forma was then completed using only the emergency department notes including details of patient demographics, circumstances of assault, nature of injuries, medical management and whether parents and the police and social services had been documented as informed.

In accordance with the guidelines produced by the Advisory Group on the Operation of NHS Research Ethics Committees, no explicit ethical approval was needed for this audit led by service needs.8

Results

Data collection and demographics

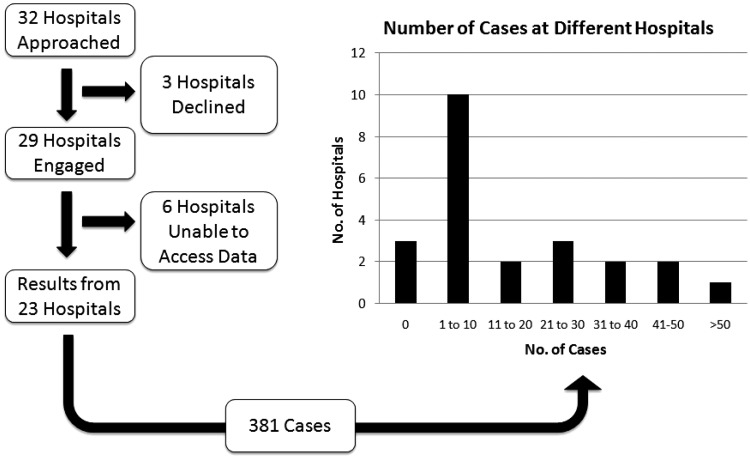

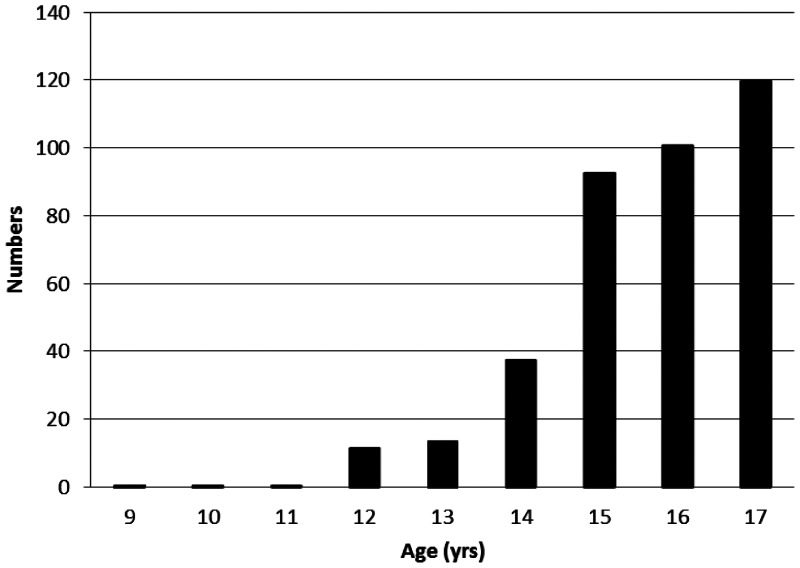

Of the 32 emergency departments in London, 29 participated in this study. Six departments were unable to identify cases and so could not provide data. Three hospitals reported no cases. From the remaining 20 hospitals, 381 presentations of stabbing were reported (Figure 1). Of the 381 presentations, 160 were of children less than 16 years old. The age distribution is shown in Figure 2. The male:female ratio was 10.5:1. The majority of cases presented outside normal working hours with 25% presenting between 1700 and 2100 and 64% between 2100 and 0900. Fifty-three percent were documented as presenting accompanied by the emergency services (either London Ambulance Service or Metropolitan Police). In 35% (19% for those <16 years), there was no documentation as to who they were accompanied by.

Figure 1.

Data collection; responses from Emergency Departments and distribution of cases.

Figure 2.

Age distribution of cases. Of the 381 cases, 160 were in young people less than 16 years old.

Characteristics of assault

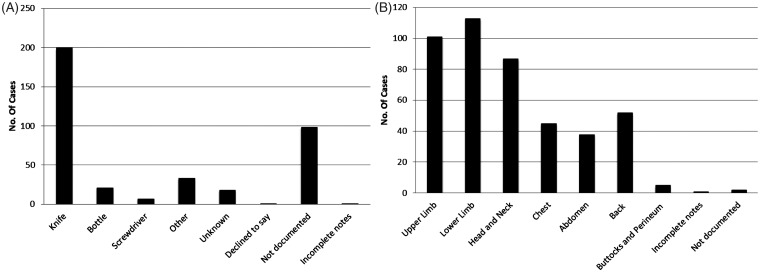

A knife was the documented weapon in 52% of cases followed by a bottle in 5% (Figure 3). In 25%, there was no documentation within the emergency department notes about what type of weapon was used. Other weapons included broken glass, machetes, screwdrivers and axes.

Figure 3.

Nature of assault. (A) Weapons used. (B) Site of injury. 21% of presentations had wounds to >1 site.

The street was the commonest documented location of assault (29%) (in 39% no location was documented). There were also a number of stabbings in the home (n = 21) and at schools (n = 27).

The assailant(s) were documented as ‘gang’ or ‘group of youths’ in 50 cases. In 47%, the assailant was documented as ‘unknown’; however, on discussion with staff working in departments with high case loads, they felt that in a proportion of such cases the assailant was known, but the victim did not wish to disclose. In 38%, details of the assailant were not documented.

Nature and management of injury

The limbs were the commonest site of injury (upper limb, n = 101; lower limb, n = 113). The head and neck were injured in 87 presentations, the chest in 45 and the abdomen in 38 (Figure 3). In 21% of presentations, injuries were recorded in more than one of these areas.

The majority of patients were seen by emergency department doctors, and 58% were only seen by an emergency department doctor. Twenty-eight percent of cases were admitted. Three patients in this cohort died within the emergency department.

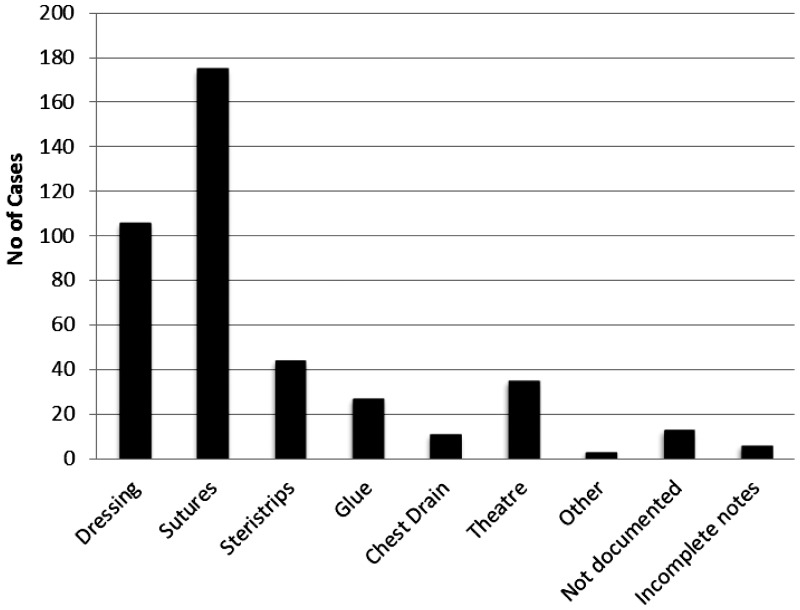

Most cases required simple management (dressings/sutures/strips/glue) (Figure 4). However, a significant minority, 12% (16% of <16 year olds), required more invasive management either through insertion of chest drains or an operation.

Figure 4.

Management of cases. 28% of cases were admitted. 12% (16% of those <16 year old) required either surgery or chest drain insertion.

Safeguarding procedures

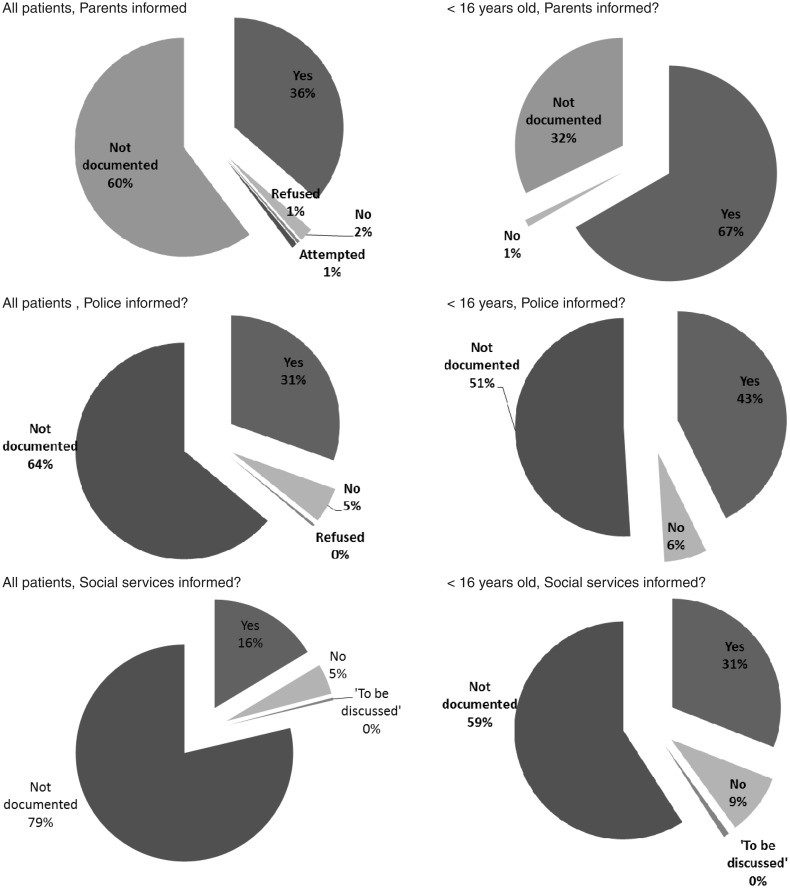

Of patients discharged directly from emergency departments the proportion of cases in which parents and the police and social services were documented as being informed is summarized in Figure 5. These results show overall documented referral rates to the police and social services of 31% and 16%, respectively. In a high proportion (64% and 79%, respectively), there was no documentation relating to these safeguarding procedures within the emergency department notes. Whilst rates were higher when analysis was restricted to those <16 years old, documentation remained poor and documented referrals to the police and social services remained below 50%.

Figure 5.

Child protection procedures. Documented referral rates of patients discharged from Emergency Departments. Documented rates of informing parents, Police and Social Services. n = 263 for all patients, n = 110 for those patients<16 years old. (23 [14 for <16 year olds] excluded from ‘Parents informed?’ as data not collected in pilot study, eight further patients excluded due to incomplete/unavailable notes.)

Further findings

Though not designed to identify such cases, this study identified two cases whereby a young person presented with one minor stabbing and later represented following a more serious stabbing at a later date. In both cases, there was no documentation of informing the police or social services at first presentation.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the scale of morbidity caused by knife crime and stabbing within the capital, in addition to the more publicized mortality. The majority of cases identified in this audit were minor injuries, generally presenting out of hours to emergency department doctors and not requiring admission. Of concern, but in accordance with past anecdotes, some of these young people returned at a later date with more severe injuries. This highlights the vulnerable position in which some young people live and highlights the need to consider and address safeguarding and social issues in such patients. Of these discharged young people, documentation regarding referral rates to the police and social services was generally poor. Where documented, referral rates were low. In addition, documentation regarding the circumstances of the assault was also generally low. Such information is of importance when assessing the risk of future harm to the child.

The nature of the computer systems, coding, the three hospitals that did not take part and the exclusion of minor injury and ambulatory units will have led to this audit missing a substantial proportion of cases.

Only emergency department notes were studied; therefore, this audit is likely to underestimate referrals to police and social services as it will have missed cases where referrals were made but not documented, made prior to arrival by emergency services or later through safety net procedures, which may not be documented in these emergency department notes. Social services will also be informed by the police through the Form 78/Merlin system. Consequently, referral rates are likely to be higher than shown in Figure 5. However, we believe that doctors should be considering these patients in the same manner as cases of suspected non-accidental injury child maltreatment in younger children; in particular, ensuring that discussions and decisions regarding child protection issues and referrals are clearly documented within emergency department notes.

Despite missing a large number of cases, this is the largest cohort of paediatric stab victims studied and gives us valuable information about the nature of such stabbings in children and young people and their management within emergency departments in London. These results also demonstrate how paediatric stabbing is a problem not only limited to trauma centres, but seen right across the capital’s hospitals. Whilst the development of the trauma network will alter the hospital of presentation of major trauma patients, a substantial proportion in this cohort self present and the majority of this cohort were minor injuries. Consequently, paediatric stabbing is likely to continue to be seen in the majority of emergency departments across London.

The timeframe of this audit necessarily resulted in comparing existing practice with a new standard and so re-audit covering a period subsequent to the General Medical Council guidelines is essential to ensure that practice has improved and to continue the audit cycle. This is ongoing in several trusts. To promote the improvement of such practice, the results of this audit have been distributed to emergency departments across London, and at National Meetings, emphasizing that child protection processes should be considered for all paediatric victims of stabbing, and that such patients should be managed in the appropriate manner as non accidental injury/child maltreatment. Specific education of staff has also occurred in some trusts.

Whilst this study was carried out within London, 58% of stabbings in England occur outside the capital.3 The results of this study, particularly the large numbers of minor injuries, and the previously unmet need to address the social aspects of these patients’ care are applicable across the UK, and particularly in other urban centres. Though legislation and recommendations vary across the globe, a non-accidental stab wound to any child should raise concerns for their future safety.

DECLARATIONS

Competing Interests

None declared

Funding

None declared

Ethical approval

In accordance with the guidelines produced by the Advisory Group on the Operation of NHS Research Ethics Committees, no explicit ethical approval was needed for this audit led by service needs

Guarantor

AGS

Contributorship

Pilot study conducted by SG. AGS led the Pan-London study which was co-ordinated by JRA and CW. Further contributors are acknowledged in the acknowledgements. AM provided expert Accident and Emergency Input. The paper was prepared by JRA and reviewed and modified by all other authors

Acknowledgements

We thank the following contributors for the efforts in collecting and submitting data: Abbas Khakoo, Adrian Jugdoyal, Amutha Anapantha, Anthony Gareats, Cherry Alviani, Dan Harris, Deniz Gurtin, Didi Ratnasinghe, Duncan Brooke, Ed Abrahamson, Fernand Ohanusi, Geraint Morris, Gillian Park, Harry Woodwood, Helen Doolittle, Jane Bayreuther, Johanna Reed, John Jackman, John Knottenbelt, Jon Lewin, Judah Eastwell, Julie Bak, Kat Hunter, Kumudini Gomez, Laiy Pourghomi, Louise Woodgate, Mary Doyle, Melanie Chan, Nandita Parmar, Nick Ware, Nicola Brown, Nicola McDonald, Nilesh Patel, Paul Riley, Phil Dart, Rachel Moll, Rahul Chodhari, Rashmi Patel, Rita Das, Rumina Hassan-Ali, Ruth Mew, Sabeena Obaray, Sarah Mills, Sathish Bangalore, Sharmi Sivakumaran, Sophie Davis, Sophie Weiss, Su Blackburn, Susie Gabbie, Syed Masud, Tom Rossor, Turan Huseyin, Vanessa Chow and William Glazebrook. In addition, we thank the background administrative staff across all participating hospitals for their help and support.

Provenance

This article was submitted by the authors and peer reviewed by Szymon Tokarczyk

References

- 1. Konig T, Knowles CH, West A, et al. Stabbing: data support public perception. BMJ 2006; 333: 652–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crewdson K, Lockey D, Weaver A, Davies GE. Is the prevalence of deliberate penetrating trauma increasing in London? Experiences of an urban pre-hospital trauma service. Injury 2009; 40: 560–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berman G. Knife Crime Statistics. Standard Note SN/SG4304, London: House of Commons Library, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 4. See http://www.met.police.uk/crimefigures/ (last checked 13 April 2013)

- 5. See http://www.crimesurvey.co.uk/ (last checked 21 April 2013)

- 6. MORI Five-Year Report: An Analysis of Youth Survey data. See http://yjbpublications.justice.gov.uk/en-gb/Resources/Downloads/MORI5yr.pdf (last checked 21 April 2013)

- 7. General Medical Council. Confidentiality: Supplementary Guidance, GMC 2009. London: General Medical Council, 2009.

- 8. Ad Hoc Advisory Group on the Operation of NHS Research Ethics Committees, Differentiating Audit, Service Evaluation and Research. November 2006. See www.nres.nhs.uk (last checked 21 April 2013)