Abstract

The acutely swollen knee is a common presentation of knee pathology in both primary care and the emergency department. The key to diagnosis and management is a thorough history and examination to determine the primary pathology, which includes inflammation, infection or a structural abnormality in the knee. The location of pain and tenderness can aid to localization of structural pathology even before radiological tests are requested, and indeed inform the investigations that should be carried out. Aspiration of an acutely swollen knee can aid diagnosis and help relieve pain. The management of the swollen knee depends on underlying pathology and can range from anti-inflammatory medication for inflammation to operative intervention for a structural abnormality.

Introduction

The knee is injured more frequently than any other joint in the body because it is part of a weight-bearing limb, and second, it does not have the stability procured by the joint congruity of the hip and ankle.1

As with all conditions, a thorough history and examination often provides enough information for a provisional diagnosis to be made, the need for onward referral to be determined and investigations to be instituted.

Aims of the review

This review aims to inform those in the primary care and emergency department setting as to how to assess and manage the swollen knee.

The review was performed by selecting appropriate papers from a PubMed search using the terms ‘swollen knee’ and ‘knee swelling’, ‘knee effusion’ and ‘knee haemarthrosis’ and combining this with the senior author's (CG) own experiences.

Anatomy

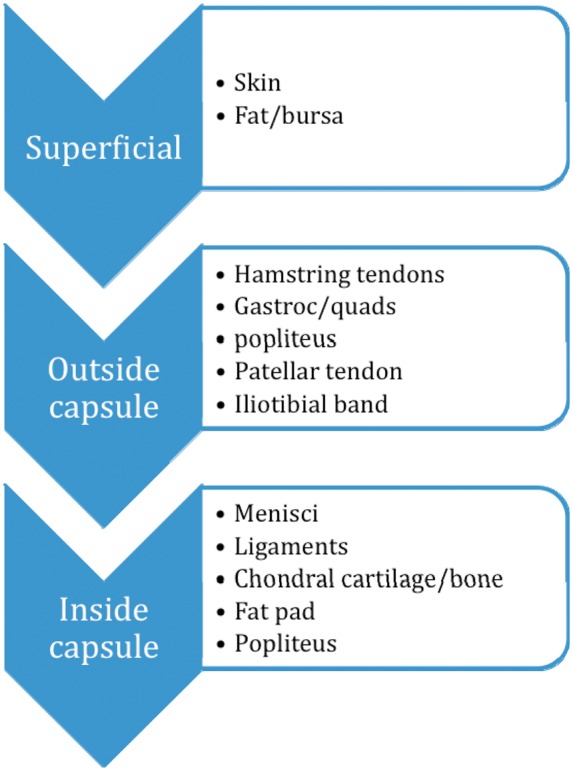

In determining the causes of an acutely swollen knee one should think anatomically (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Anatomically determining the causes of acutely swollen knee pathology (referred pain from the back, hip and nerves not included)

Pain

The presence of pain in the swollen knee should trigger a thorough pain history. This includes:

Site of pain. Approximately 69% of patients can localize their pain and point to a specific area in the knee that the pain occurred.2

Factors that exacerbate or bring on the pain are also important. For example, if the pain is particularly worse when the patient is twisting or turning at pace, this may indicate either a meniscal tear or instability related to a cruciate ligament injury.

Aetiology of knee pain

Pain when ascending or descending stairs may indicate pathology from the patellofemoral joints. This is a direct result of the increase contact pressures on the patella when the knee is loaded in a flexed position.3 There is an increased incidence of patellofemoral disorders in women.4

Night pain is red flag symptom. The most common cause of night pain in the adult is a severe degenerative arthritis.5 However, night pain in a child or a young adult may indicate an underlying pathology such as infection or neoplasm. The presence of night pain in an older patient with normal plain radiology of the knee may also be a red flag symptom.

Localization of pain

It is important to bear in mind the possibility of referred pain either from the spine or the ipsilateral hip.

The patient's description of knee pain is helpful in the differential diagnosis.6 Most patients are able to localize the pain in their knees to either the medial or lateral side or the posterior aspect. Some patients describe the pain as being ‘all around their knee’ or on the anterior aspect. The broad categories of knee pathology can be cross-referenced against the descriptive location of the pain. These can be further subdivided into pathologies relating to specific age groups as shown in Table 1. While these are generalizations, and there is significant cross-over, this does allow the clinician to establish some form of diagnostic framework (Table 1).

Table 1.

Table of diagnostic framework for aetiology of knee pain depending on location of pain and age of patient

| Age (years) | 9–15 | 15–30 | 30–60 | >60 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location of pain | ||||

| Anterior/stair pain | Chondromalacia/Osgood – Schlatter disease | Chondromalacia/patellar maltracking (and dislocation)/ jumper's knee/fat pad inflammation/saphenous nerve irritation/bursitis | Left column plus osteochondral defect patella/ | Patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis (PFJ OA) |

| Medial | Medial meniscus tear, osteochondritis dissecans/medial collateral ligament (MCL) injury | Left plus ostochondral defect/injury/pes anserinus bursitis | Left plus medial OA/SONK | Medial OA/SONK |

| Lateral | Discoid lateral meniscus (LM) osteochondral defect | Plus LM tear/popliteus syndrome/ lateral collateral ligament (LCL) injury/ lliotibial band (ITB) syndrome | Plus lateral OA/ Lateral PFJ OA | Lateral OA/PFJ |

| Posterior | MM/LM tear/tumour/ popliteus pathology/ sciatic/tibial nerve irritation | Baker's cyst/popliteal aneurysm/sciatic referred pain | ||

| Non-specific | Exclude referred pain from hip/spine/tumour/ infection/inflammation | |||

Mechanism of injury

When the injury occurs during sport, it is important to determine whether or not the patient was able to continue his/her sport or weight bear immediately after the injury. If not this implies a more severe injury, perhaps of the ligaments or bones. In terms of the direction of impact of the knee, some patients are able to determine whether their knee deformed into hyperextension, varus or valgus, or into a rotatory deformity. It is possible to speculate on the structures that may have been injured according to the deforming forces in the knee. For example, a tackle to the outside (lateral) aspect of the knee playing rugby would result in a valgus deforming force, thus stretching or tearing the medial collateral ligament.

A direct blow to the front of the knee may damage the patellofemoral joint; a blow to the side may rupture the collateral ligament; twisting injuries are more likely to cause a torn meniscus or a cruciate ligament tear.7

Non-contact forces are also an important cause of knee injury. A study examining the mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury reported 71% were due to non-contact and 28% due to contact (one patient was unsure of mechanism of injury). Most of these were sustained at foot strike with the knee close to full extension and landing in external rotation. Non-contact forces were classified as sudden deceleration prior to change of direction or landing motion, while contact injuries occurred as a result of valgus collapse of the knee.8

Onset of swelling

A swelling that occurs immediately after an injury is suggestive of a significant haemarthrosis, i.e. bleeding due to damage to a structure such as bone or ligament. Classically, a swelling that occurs 24–36 h after injury can be due to either a sympathetic effusion or a slowly forming haemarthrosis, caused, for example, by a meniscal injury.9

Associated symptoms

Red flag symptoms include fevers and sweats with the sensation of heat in the knee. These are suggestive of an infective pathology, especially in the absence of an associated injury. However, a resolving haemarthrosis may also cause some warmth in the knee. In either case, a patient with a haemarthrosis should be regarded as having a serious ligament or bony injury until proved otherwise.10 The presence of a fat fluid level on a lateral X-ray implies a lipohaemarthrosis, which is pathognemonic for an intrarticular knee bone fracture.

Locking and giving way

Symptoms of locking may occur immediately after injury or more commonly, after the initial acute, severe phase of injury has resolved. These symptoms are suggestive of a mechanical block, usually to extension in the knee.

Causes of mechanical block include:

Loose body;

A torn piece of meniscus caught between the femoral and tibial condyles;

Chondral or osteochondral fragments;

Occasionally, a torn anterior cruciate ligament with tissue blocking extension.

Giving way can be caused by the mechanical block as above, or instability from ligamentous pathology. Sportsmen often describe instability as the inability to “trust their knee”, especially when turning at pace. One further cause of locking or giving way is a perceived mechanical phenomenon due to patellofemoral pathology, either patellofemoral chondral wear, degeneration or mal-tracking. While this is not a true mechanical locking the patient perceives the sensation of locking, particularly after rising from a seated position after a long period or when squatting.11

Disability

The degree of difficulty the patient experiences with mobilization indicates the disability the patient is suffering as a result of their knee pain. In older patients studies have shown that function in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis (OA) is determined more by pain and obesity than by radiological structural changes.12 In these patients it is therefore essential to assess mobility, ability to perform shopping and limitation of activities of daily living before considering treatment.

In younger, more athletic patients, specific sporting activities require the ability to perform specific knee movements. For example, a rugby player with a anterior cruciate tear may be asymptomatic with his day-to-day activities off pitch but be unable to perform pivoting movements at an increased pace during the game and thus warrant surgical intervention.

Childhood infection and deformity should be inquired of

History of childhood infection or deformity may be predisposed to early degenerative change.13

Treatments that have already been instituted

Many patients have undergone physiotherapy, steroid injection or previous arthroscopy. The success of previous therapies guides further management.

If a patient has not undergone physiotherapy this may be the first port of call particularly in anterior knee pain related to patellofemoral joint dysfunction. History of previous surgery, in particular total knee replacement or cruciate ligament reconstruction, associated with new onset of symptoms should warrant a referral to the orthopaedic surgeon.

Examination

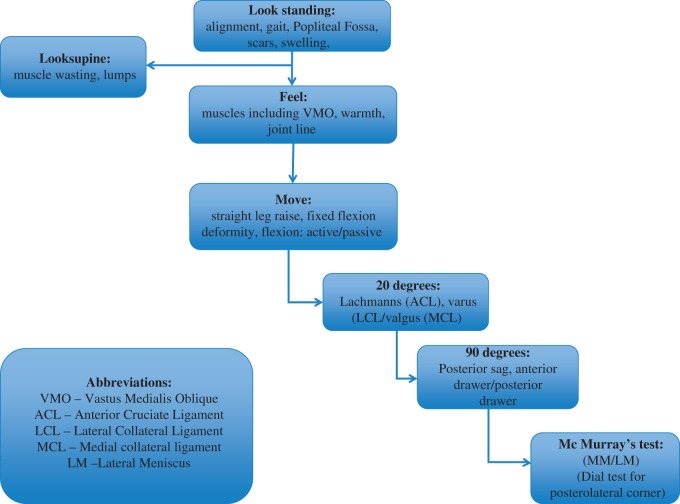

When palpating the knee, it is particularly important to appreciate the anatomical structures that are being palpated. Muscle wasting is also appreciated better when the muscles are palpated in contraction rather than just inspected (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram summarizing the sequential steps required to perform an adequate examination of the knee joint

The ‘straight leg raise’: distinguishing fixed flexion from extensor lag

An intact straight leg raise implies an intact extensor mechanism. If the patient is able to straight leg raise with no flexion deficit this implies a fully functioning, strong intact extensor mechanism.

However, if the patient can only perform a ‘straight leg raise’ by lifting the knee in flexion, and this flexion does not disappear passively, this implies a flexion deformity. If the flexion deficit corrects passively this implies an extensor lag, indicating a weakness of the extensor mechanism (Video 1).

Anterior cruciate ligament testing

The anterior drawer should be performed at 80 degrees of flexion. It is essential that the hamstring tendons be palpated to ensure that these are relaxed. The anterior drawer should be performed with the thumbs over the tibial tubercle with a gentle rocking movement backward and forward from the examiner, carefully inspecting the tibial plateau at the joint line (see Picture 1). If the examiner sits on the ipsilateral foot, the patient should be warned of this prior to sitting. The anterior drawer is graded I = increased compared with unaffected side but with good end point (0–5 mm displacement), II soft end point, (5–10 mm), III grossly lax >10 mm.

The posterior drawer test is similarly performed and graded but with a posterior force being applied to the tibia.

Lachmann's test is performed at between 20 and 30 degrees of flexion. The best way to relax the hamstring tendons is to rest the ipsilateral thigh over the examiner's contralateral knee at the level of the mid thigh. A gentle anterior translation of the tibia is attempted on the femur (Figure 2).

Picture 1.

Demonstration of an anterior draw test

The Lachmann's test is regarded as more sensitive than the anterior drawer test especially in acute ruptures.14

The ACL consists of two functional bundles: anteromedial and posterolateral. The Lachmann's test, notionally at least, stresses the posterolateral bundle of the anterior cruciate ligament whereas the anterior drawer test stresses the anteromedial bundle of the ACL.

Other tests

Varus and valgus testing should be performed at 0 and 20 degrees. At 0 degrees the posterior capsule acts as a secondary restraint to varus and valgus. At 20 degrees varus and valgus are thought to be primarily due to the lateral collateral and medial collateral laxity, respectively.

Thus, a knee that shows excessive varus or valgus in extension indicates more damage to the soft tissue, which may include the posterior capsule.

The McMurray's test has been classically described to examine for a meniscal tear. This test can irritate the patient and cause pain and is not advised to be performed with a patient with an irritable knee. However, it is possible to perform a McMurray's test on patients with less irritable, less apprehensive knees.

The dial test can be performed either prone or supine and is for posterolateral corner instability.

Finally, it is important to complete any examination with an assessment of the neurovascular status of the limb.

Further videos are available online.

Referral to a specialist

When considering a referral, this physician should ask question ‘Does this patient need further diagnosis or operation?’ (Table 2).

Table 2.

Indications for referral to specialist

| Indications | |

|---|---|

| Red flag symptoms | Night pain, weight loss, fevers or history of cancer |

| Persistent pain | Failed physiotherapy, recurrent unexplained pain |

| Previous surgical intervention | Previous joint replacement or ligament reconstruction |

| Multiple pathology involving the spine, hip and knee | Suspected inflammatory arthropathy |

Specialist referrals should be sought if an acute knee injury is suspected, in particular suspected ligament injury, meniscal tear or bony injury.

One other indication for specialist referral is if the source of pain is suspected as referred or multifactorial. Knee pain referred from the hip or concomitant hip or knee degenerative change or arthritis may require diagnostic local anaesthetic injection into either the hip joint or the knee joint to determine the exact nature of the pain.15

Conventionally, concomitant ipsilateral degenerative hip and knee pain should be dealt with by performing the hip replacement prior to knee replacement. This is because studies have shown knee pain to improve after ipsilateral hip arthroplasty.16

Equip the patient adequately to ensure efficiency of a specialist opinion

It is valuable in having the history and examination in the referral letter.

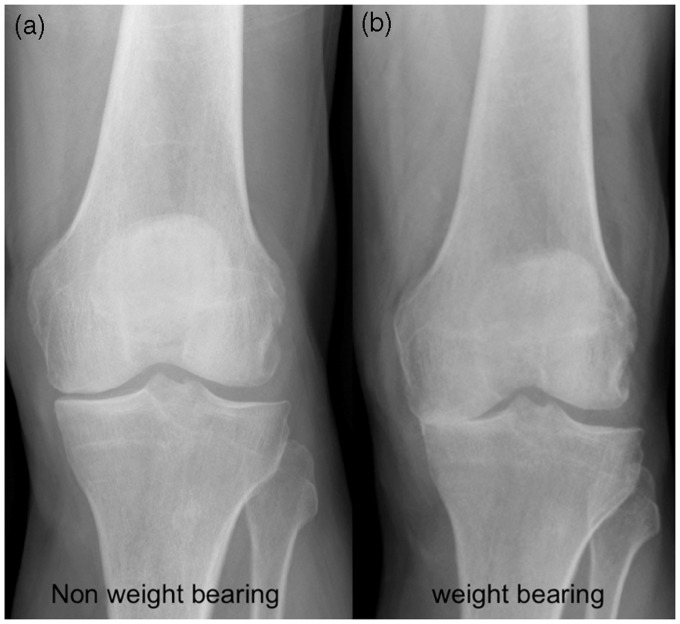

Weight bearing AP, lateral and skyline views of the knee are also of value. If the patient can weight bear, these provide far more information regarding the degree of degenerative changes as the weight-bearing status stresses the knee and reveals degenerative change that may not be otherwise revealed by a pain supine view (Figure 3).17

Figure 3.

Non-weight-bearing (left) and weight-bearing (WB) (right) views of the same knee demonstrating predominantly medial compartment OA, which is only apparent in the WB views

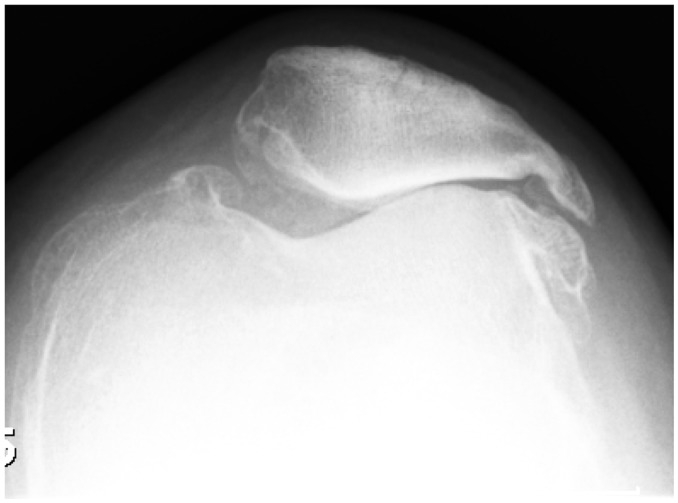

Skyline views of the patella are of value to eliminate patellofemoral degenerative change (Figure 4).18

Figure 4.

A skyline view of a left knee demonstrating patello-femoral OA

MRI scan

MRI scans are of value only if an adequate history and examination has been performed, as the details on the request form help focus the radiologist when reporting the scans.

In older patients (>65 years) the presence of a pathology and MRI scan does not necessary indicate the exact cause of pain.19

Many patients aged over 65 years will demonstrate on MRI scanning either patellofemoral degenerative change or medial meniscal tear, or commonly both pathologies. Clinical tenderness over the medial joint line will help determine if the medial meniscal tear is symptomatic and truly the cause of the patient's symptoms, or whether this is an incidental finding.

Therefore, MRI scans are advised in patients aged less than 60 years with suspected meniscal ligament injury or a lump or recurrent anterior knee pain.

In those patients over the age of 60 years an MRI scan, in the primary care setting, is recommended in the presence of a normal plain radiograph, or if there are red flag symptoms or a specific pathology is being sought after (e.g. spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee [SONK]).

Other investigations, bone scans can be performed to investigate multiple joint pains, or if neoplasm is suspected.

Haematological markers

Relevant hematological markers are listed in Table 3.

Aspiration of a swollen knee

Aspiration of a swollen knee can aid diagnosis, as the aspirate can be tested for microscopy, culture and sensitivity and for crystals present in conditions such as gout. Aspiration of an acutely swollen knee may yield either frank blood, indicating a significant ligament or meniscal injury, or blood mixed with fat globules (lipohaemarthrosis), which is pathognemonic of a fracture.

Table 3.

Valuable blood tests

| Test | Indications |

|---|---|

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate/c reactive protein | Infection/inflammation |

| Vitamin D | Ethnicity, wearing covered clothing (e.g. burkha), vegan diet |

| Alkaline phosphatase | Bone enzyme activity |

| Calcium | Disorders of calcium metabolism (e.g. hypo/hyperparathyroidism) |

| Auto-antibodies (e.g. Rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide) | Autoimmune diseases (e.g. Rheumatoid arthritis) |

A trained professional should carry aspiration out using sterile aseptic non-touch technique with local anaesthetic infiltration via a superolateral approach to the joint with the patient supine. In the acute setting aspiration of a tense haemarthrosis can provide good symptomatic relief.

Management of common conditions

Meniscal tears

The management of meniscal tears depends on the symptoms and degree of disability. A locked knee (implying the inability to extend the knee) does require emergency treatment in the form of MRI scan followed by arthroscopy to either repair or resect the meniscus causing the locking.20

Peripheral meniscal tears which are undisplaced with only minor symptoms of pain but no mechanical symptoms or locking, can be managed conservatively in the first six weeks with the restriction of activity including deep flexion, and twisting, as these can heal.

It is especially important that in the older patient, the clinician distinguishes anterior knee pain as a result of patellofemoral pathology, from medial pain due to a medial meniscal tear.

In most patients with a meniscal tear, who are symptomatic for greater than six weeks, arthroscopy is required.

Arthroscopy can involve either repairing or resecting the torn meniscus.

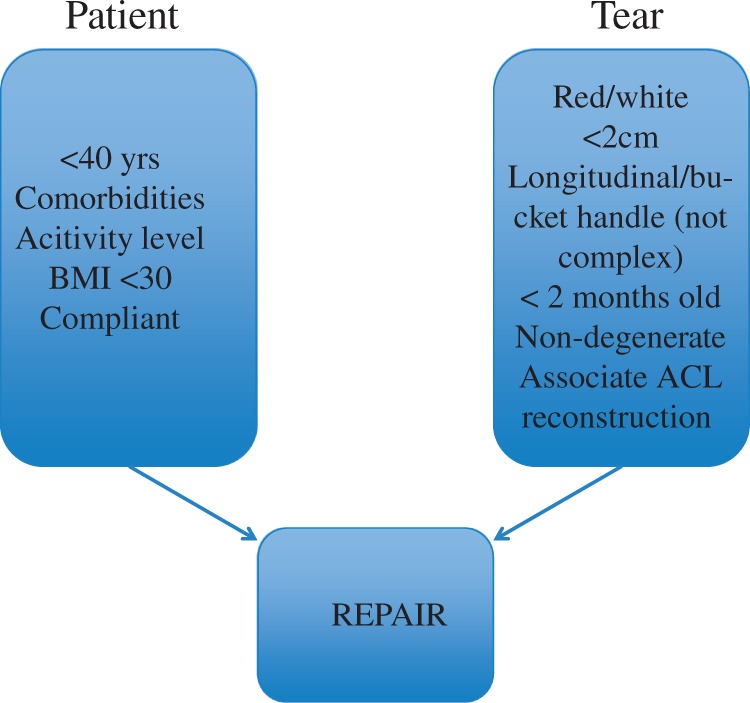

Certain tears that are amenable to arthroscopic repair

These include a tear in a young patient (aged < 40 years) which is less than six weeks old and is peripheral and longitudinal in nature.21 In children and adolescents, there should an especially low threshold for repairing the meniscus if at all possible, as resection can predispose to early degenerative change (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Indications for meniscal repair rather than resection

Anterior cruciate ligament injury

Determining whether or not an anterior cruciate ligament rupture requires conservative or surgical management is a clinical challenge. A Cochrane review in 2005 showed there was insufficient evidence to determine current practice.22 In reality, however, our decisions are made by assessing:

Age of patient, younger patients (<20 years) have a poorer prognosis when managed conservatively, as they are more likely to develop early degenerative change than if ACL reconstruction is undertaken.23

Activity demands of the patient: a patient aspiring to continue contact sports, twisting sports (e.g. squash, skiing), is more likely to experience giving way of the ACL-deficient knee and require reconstruction.

Obesity: reconstruction is less likely to succeed in a patient with a BMI > 30.24

There is significant debate as to which type of graft to use for ACL reconstruction. Most popular options include autograft (hamstring or patella tendon) or allograft from cadaveric donors. Current literature recommends the use of autograft in young athletes, as those treated with allograft ACL reconstruction were significantly more likely to experience clinical failure requiring revision reconstruction.25

There has also been literature on artificial grafts such as the LARS ligament but these are still not widely used due to the poor performance of artificial grafts in the past.26

Osteoarthritis in the knee

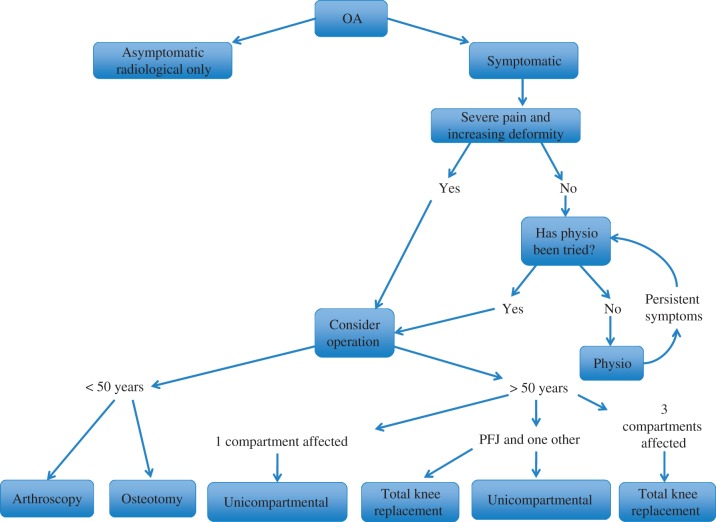

Figure 6 shows a decision tree for OA of the knee.

Figure 6.

Flow chart of treatment pathways for OA

The decision for treatment is determined by:

Patient symptoms (e.g. rest pain, night pain, mobility less than half a mile warrants arthroplasty);

Patient preference and expectations;

Radiological or arthroscopic evidence of severity and extent of arthritis (Figure 6).

Picture 2.

Demonstration of Lachmann's test

Conclusion

An adequate history and examination is essential in managing the patient with an acutely swollen knee.

The indication for operation depends on the underlying pathology, the degree of symptoms that the patient experiences and patient preference/expectations.

Specialist referral is encouraged in patients with intense swelling, a locked knee, suspected fracture or with recurrent swelling. The presence of red flag symptoms should also stimulate referral.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

None declared

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Guarantor

CG

Contributorship

Both the authors

Acknowledgements

None

Provenance

Submitted; peer reviewed by Sulaiman Alazzawi

References

- 1. Kruseman N, Geesink RGT, van der Linden AJ et al. Acute knee injuries: diagnostic & treatment management proposals. See http://arnos.unimasas.nl/show.cgi?fig1?46875 (last checked 5 April 2013)

- 2.Thompson LR, Boudreau R, Hannon MJ, et al. The knee pain map: reliability of a method to identify knee pain location and pattern. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61: 725–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powers CM, Lilley JC, Lee TQ. The effects of axial and multi-plane loading of the extensor mechanism on the patellofemoral joint. Clin Biomech 1998; 13: 616–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Csintalan RP, Schulz MM, Woo J, McMahon PJ, Lee TQ. Gender differences in patellofemoral joint biomechanics. Clinical Orthopaed Related Res 2002; 402: 260–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolhead G, Gooberman-Hill R, Dieppe P, Hawker G. Night pain in hip and knee osteoarthritis: a focus group study. Arthritis Care Res 2010; 62: 944–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergfeld J, Ireland ML, Wojtys EM, Glaser V. Pinpointing the cause of acute knee pain. Patient Care 1997; 31: 100–7 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Louis S, Warwick D, Nayagam S. Apley's System of Orthopaedics and Fractures. Edition 8, London: Hodder Arnold Publishers, 2001.

- 8.Boden BP, Dean GS, Feagin JA, Jr, et al. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Orthopedics 2000; 23: 573–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Calmbach W, Hutchens M. Evaluation of patients presenting with knee pain: part 1. History, physical examination, radiographs and laboratory tests. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:907–12. [PubMed]

- 10.Maffulli N, Binfield PM, King JB, Good CJ. Acute haemarthrosis of the knee in athletes. A prospective study of 106 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1993; 75: 945–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixit S, DiFiori JP, Burton M, Mines B. Management of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Am Fam Physician 2007; 75: 194–202 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creamer P, Lethbridge-Cejku M, Hochberg MC. Factors associated with functional impairment in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000; 39: 490–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nade S. Acute septic arthritis in infancy and childhood. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1983; 65: 234–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitsou A, Vallianatos P. Clinical diagnosis of ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament: a comparison between the Lachman test and the anterior drawer sign. Injury 1988; 19: 427–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crawford RW, Gie GA, Ling RS, Murray DW. Diagnostic value of intra-articular anaesthetic in primary osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1998; 80: 279–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W, Geller JA, Nyce JD, Choi JK, Macaulay W. Does ipsilateral knee pain improve after hip arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470: 578–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altman RD, Fries JF, Bloch DA, et al. Radiographic assessment of progression in osteoarthritis. Arthritis & Rheum 1987; 30: 1214–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies AP, Vince AS, Shepstone L, Donell ST, Glasgow MM. The radiologic prevalence of patellofemoral osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002; 402: 206–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phan CM, Link TM, Blumenkrantz G, et al. MR imaging findings in the follow-up of patients with different stages of knee osteoarthritis and the correlation with clinical symptoms. Eur Radiol 2006; 16: 608–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson MW. Acute knee effusions: a systematic approach to diagnosis. Am Fam Physician 2000; 61: 2391–400 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shybut T, Strauss EJ. Surgical management of meniscal tears. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 2011; 69: 56–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linko E, Harilainen A, Malmivaara A, Seitsalo S. Surgical versus conservative interventions for anterior cruciate ligament ruptures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 18: CD001356–CD001356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mizuta H, Kubota K, Shiraishi M, Otsuka Y, Nagamoto N, Takagi K. The conservative treatment of complete tears of the anterior cruciate ligament in skeletally immature patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995; 77: 890–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kowalchuk DA, Harner CD, Fu FH, Irrgang JJ. Prediction of patient-reported outcome after single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 2009; 25: 457–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pallis M, Svodoba SJ, Cameron KL, Owens BD. Survival comparison of allograft and autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction at the United States Military Academy. Am J Sports Med 2012; 40: 1242–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Machotka Z, Scarborough I, Duncan W, Kumar S, Perraton L. Anterior cruciate ligament repair with LARS (ligament advanced reinforcement system): a systematic review. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol 2010; 7: 29–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]