Abstract

Occlusions in single cortical microvessels lead to a reduction in oxygen supply, but this decrement has not been able to be quantified in three dimensions at the level of individual vessels using a single instrument. We demonstrate a combined optical system using two-photon phosphorescence lifetime and fluorescence microscopy (2PLM) to characterize the partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) in single descending cortical arterioles in the mouse brain before and after generating a targeted photothrombotic occlusion. Integrated real-time Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging (LSCI) provides wide-field perfusion maps that are used to monitor and guide the occlusion process while 2PLM maps changes in intravascular oxygen tension. We present the technique’s utility in highlighting the effects of vascular networking on the residual intravascular oxygen tensions measured after occlusion in three dimensions.

OCIS codes: (170.0170) Medical optics and biotechnology, (170.3650) Lifetime-based sensing, (170.1460) Blood gas monitoring, (170.5380) Physiology, (180.4315) Nonlinear microscopy, (110.6150) Speckle imaging

1. Introduction

The distribution of dissolved oxygen in the brain has proven difficult to examine at the microvascular level under baseline conditions let alone after selective flow alterations due to methodological shortcomings of classical oximetry techniques. Empirical measurements are often still made outside the vascular lumen of large vessels through invasive Clark electrodes [1,2] from which mathematical models of oxygen delivery have been developed following the theory of advection-diffusion [3,4]. More recently, three-dimensional optical imaging techniques have been shown to provide hemodynamic characterization of microvascular beds with greater sensitivity and accessibility without significant physiological perturbation [5].

In particular, techniques combining laser scanning microscopy and phosphorescence quenching for oxygen measurements have begun mapping microvascular oxygen tension. However, these techniques have proven challenging for three dimensional imaging with conventional oxygen sensitive probes [6,7] due to very low two-photon absorption cross-sections and skewed calibrations at high probe load.

A new platinum-porphyrin based phosphorescent oxygen sensor, PtP-C343 [8] has been developed with a much larger two-photon cross-section, tuned oxygen sensitivity and greater molecular dispersion in biological environments. These properties combined with its phosphorescence efficiency make PtP-C343 an effectively brighter and stable molecular probe for two-photon microscopy, resulting in greater confidence in measurements and improved three-dimensional sectioning. The new oxygen sensor has shown convincing calibration in vitro and in vivo through blood gas analysis along with application in a series of baseline [9,10] and functional activation [11,12] pO2 measurements in intravascular and interstitial tissue environments. Here, we demonstrate a two-photon lifetime microscopy technique that utilizes this new oxygen sensor for examining the vascular networking impact on intravascular oxygen tension.

We incorporate laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) in the combined system for monitoring regional cortical blood flow changes induced through photothrombosis. LSCI is a non-scanning technique that utilizes camera imaging, which enables scalable fields of view for fast and vast flow characterization albeit in a depth-integrated fashion. The technique’s relative simplicity has enabled it to quickly become a widely used modality in rodent cortical blood flow studies [13,14]. Given a fundamental reliance on statistical modeling, LSCI is largely limited to measuring relative blood flow changes [15]. Nevertheless, LSCI provides high temporal resolution for real-time analysis of cortical blood flow from multiple surface vessels in a complementary fashion to the absolute dynamics obtainable with two-photon imaging.

In this paper, we present a single optical system integrating the above techniques to make non-invasive cerebral blood flow and intravascular oxygen tension measurements before and after microvascular occlusions. We envision that the system can be a useful non-contact method for studying microvascular oxygen gradients and networking not only in the intact rodent brain but in other systems where microvascular flows are functionally relevant.

2. Methods

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at The University of Texas at Austin under guidelines and regulations consistent with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (PHS Policy) and the Animal Welfare Act and Animal Welfare Regulations.

2.1 Imaging and lifetime acquisition

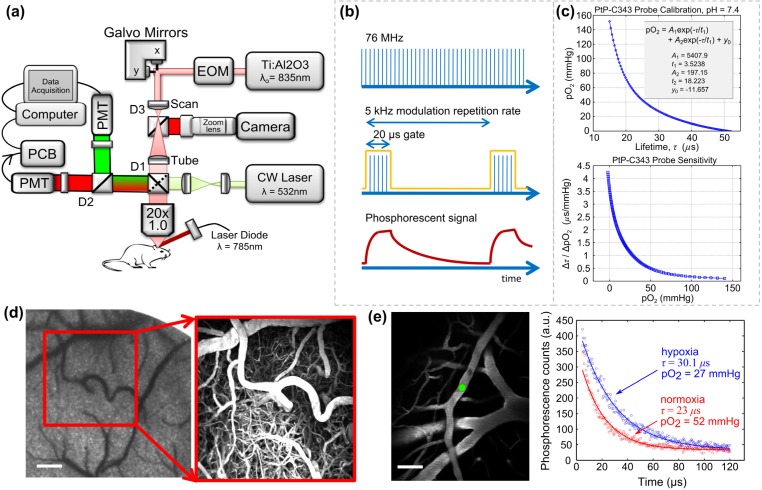

A custom-built two-photon laser scanning microscope with an integrated laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) system is presented in Fig. 1(a). A large back-aperture long working distance objective, two-inch collection optics, and un-cooled, un-housed photon-counting PMT's (H10770PB-40, Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan) were utilized to optimize collection efficiency of fluorescence and phosphorescence signals [16]. A Ti:sapphire femtosecond excitation laser (Mira 900f, 140 fs, 76 MHz, λo = 835 nm, Coherent Inc.) was tuned to optimize vascular labeling and to take advantage of the two-photon cross section of PtP-C343. An electro-optical modulator provides laser intensity control for imaging as well as temporal gating during lifetime acquisition. Laser scanning (x-y) was achieved via galvanometer mirrors and z-translation via stepper-motorization of the objective/collection subassembly. A dichroic mirror (D1) was used to separate emission from excitation. Two-channel detection enabled further spectral separation with another dichroic mirror (D2). Detected phosphorescence lifetime signals from PtP-C343 were digitized using a photon counting board (DPC 230, Becker & Hickl, Germany), while fluorescence signals were sent directly to the computer for image (Figs. 1(d)-1(e)) and linescan (Fig. 2(a)) acquisitions.

Fig. 1.

(a) Custom two-photon microscope with integrated laser speckle contrast imaging and photothrombotic light delivery. EOM: electro-optic modulator; PCB: photon counting board; D1, D2, D3 dichroic mirrors with transmissions: T > 740 nm, T > 795 nm, and T > 570 nm, respectively. (b) Laser modulation paradigm for phosphorescence measurements. Pulsed laser train is temporally gated (ON: 20 µs, OFF: 180 µs) at a 5 kHz modulation rate for measuring phosphorescence signals (see optimization in Media 1 (89KB, PDF) ) (c) Top: Sample calibration of PtP-C343. Bottom: Probe sensitivity derived from differentiating calibration curve. (d) Speckle contrast image of cortical perfusion and two photon projection of labeled vasculature over 400 µm of depth. Scale bar = 150 µm. (e) Normoxic and hypoxic phosphorescent decays from a surface arteriole (left, green circle). Scale bar = 50 µm.

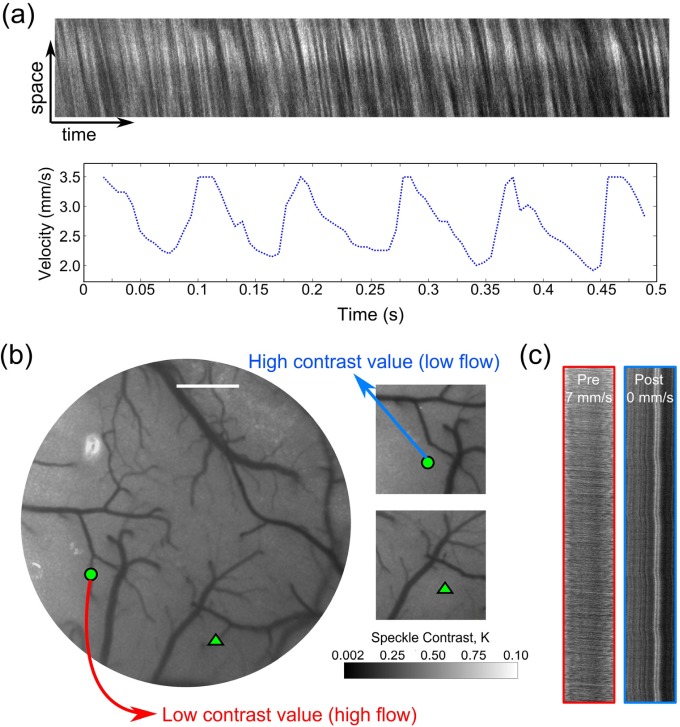

Fig. 2.

(a) Two-photon linescan from a cortical arteriole and calculated RBC speed time-course. (b) Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging of cortical flow before and after occlusion. Images shown are real-time computed speckle contrast images (5ms exposure duration) using a 7x7 pixel window, where darker pixel intensities indicate higher flow. Green circle and triangle indicate two arterioles selected for occlusion. Scale bar = 400 µm. (c) Linescans taken from Arteriole 1 (circle) are shown pre- and post-occlusion. See Media 2 (4.7MB, MOV) for real-time LSCI during photothrombosis. Intermediary halo of lower contrast around targeted vessel video are saturation artifacts of the excitation light used for photothrombosis.

The phosphorescence measurements were made in the time domain with a short gate of the pulsed excitation light (Fig. 1(b)). The instrument response was calibrated for by using a fast decaying (~4 ns lifetime) fluorescence standard to determine the temporal offset necessary to isolate the phosphorescent decay from the detected signal. After the excitation gate and offset, the remaining phosphorescent signal, I(t), was fitted for the decay constant, τ:

| (1) |

A calibration curve based on Stern-Volmer kinetics [8,17] was used to relate the lifetime measurement, τ, to a measure of pO2. Detailed calibration parameters of the probe describing the quenching efficiency under physiological conditions are shown in Fig. 1(c). The sensitivity of the probe improves with lower oxygen tensions, which lends itself to improved fidelity during the examination of deeper or higher branch order vessels and is particularly relevant for post-occlusion measurements. Temporal phosphorescence signals and their respective oxygen tensions in a cortical arteriole are shown in Fig. 1(e) under normoxic and hypoxic conditions achieved by alteration of the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2). It is important to note that the phosphorescent sensitivity is in direct contrast to the sensitivity dependence associated with Clark electrodes, where signal scales with increasing oxygen tension.

The inter-gate interval should ideally be 3-4 times longer than the longest expected phosphorescent lifetime. The unquenched lifetime of PtP-C343 is approximately 50 µs, making the lowest tolerable modulation rate to be 5 kHz. Shortening of this interval may result in insufficient sampling of the full decay and prolonging the interval (e.g. lowering the repetition rate) may reduce signal-to-noise at the decay tails. Typically, at least 12000 or 3000 excitation gates (Fig. 1(b)) have been suggested for averaging phosphorescent decays from two-photon excited focal volumes of PtP-C343 at 1% duty cycle and 10% duty cycles, respectively [10]. The number of gates is set by selecting the instrument collection time. Practically, collection times should be short enough to achieve sufficient signal-to-noise (SNR) for a desired measurement uncertainty while not delaying in vivo experiment durations excessively. A 10% duty cycle and 5 second collection time (25000 excitation gates) assured this reliability for our implementation given a priori optimization (Media 1 (89KB, PDF) ) at a fixed 6 µM probe concentration over five repeated measurements performed in vitro with an aerated saline sample. Five sequential phosphorescent decays recorded at each measurement location in vivo resulted in a 25 second temporal resolution for oxygen tension mapping. This resulted in a SNR of ~25 dB for a typical surface arteriole pO2 value of 72 ± 5 mmHg at 30 µm depth, which is an estimate of the minimum expected SNR and maximum measurement variability in this study. Particularly, SNR is of concern under high pO2 conditions (e.g. high phosphorescent quenching) and in deeper depth sections that generate and/or collect lower phosphorescence. Ultimately, the optimization of these settings is instrumentation and sample specific and therefore is necessary in anticipation of the experimental conditions.

2.2 Laser speckle contrast imaging of cortical perfusion

Regional flow maps over the cranial window were obtained using Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging (LSCI). A laser diode (λ = 785 nm) illuminated the craniotomy with oblique incidence for LSCI (Fig. 1(a)). The backscattered laser light from the specimen was imaged through the objective, passed through D1, reflected by D3 and imaged onto a camera (A641f, Basler Vision Technologies, Germany) with a zoom lens (ZOOM 7000, Navitar Inc., New York, NY). Choice of near-infrared laser diode wavelengths for LSCI is restricted by the two photon excitation center wavelength, which ultimately governs the transmission cutoff of D3. The camera focus was adjusted to be coplanar with the two photon imaging plane by coarse translation of the camera location as well as zoom lens fine focusing. Speckle contrast conversion and imaging was performed in real-time as described previously [15,18].

In brief, temporal fluctuations in the scattered laser light manifest as a blurring of the observed speckles in the image. This degree of blurring is quantified by computing the local speckle contrast (K), defined as the quotient of the standard deviation and mean pixel intensities,, over a 7x7 pixel (e.g. 9.8 x 9.8 µm in the sample plane of Fig. 1(a)) window across the raw image (not shown). Areas with higher flow in the speckle contrast images have lower contrast values and vice versa (Figs. 1(d) and 2(b)). The spatial extent of flow changes can be gauged with LSCI (Fig. 2(b)), where the gain in speckle contrast correlates inversely with the relative perfusion dynamics. Ultimately, widefield LSCI is label-free and rapid, which can be useful with 2PLM for providing multi-scale flow dynamics.

2.3 Targeted occlusion via photothrombosis

Flow interruptions are often induced by clipping large vessels upstream of the microvascular bed or introducing intraluminal sutures through the carotid artery [19–22]. These occlusion models are more suited for inducing focal to global ischemia and are too coarse and expansive for analyzing microvascular dynamics with specificity. Focused damage to the vascular endothelial lining with pulsed lasers has also recently been used to make both surface and deeper cortical occlusions in individual microvessels [23]. Studies using this occlusion model have suggested that descending arterioles serve as bottlenecks in the supply to the cortex by observing the impact on regional erythrocyte velocities [24]. This occlusion technique is promising when optimized to minimize collateral damage, but over the micro-scale there may be extravasation of blood plasma that may elevate the tissue oxygen levels and thus alter the physiological pO2 gradients acutely. Instead, we use photothrombotic occlusion of surface microvessels, which provides an optically precise mechanism for interrogating the microcirculatory flows by shutting off flow in individual vessels albeit upstream of cortical penetration.

Rose Bengal, which has been shown to be an apt photothrombotic agent with fast clearing [25–27], was injected intravenously (0.1mL, 12mg/mL dilution) immediately before green laser illumination. Targeted occlusion of a single descending arteriole upstream of cortical penetration was achieved by activation of Rose Bengal by a focused green laser (30 µm spot size, 1.5 mW, 532nm, Millenia V, Spectra Physics) introduced by switching dichroic 1 (D1) with a cold mirror (Fig. 1(a)). Real-time laser speckle contrast imaging (Fig. 2(b) and Media 2 (4.7MB, MOV) ) was utilized to monitor the occlusion progression in the vessel of interest and thereby guide the duration and location of the photothrombosis.

2.4 Animal preparation

Mice (CD-1, male, 25-30g, Charles River) were anesthetized with 80% N2/O2 vaporized isoflurane (2-3%) via nosecone. Temperature was maintained at 37°C with a feedback heating plate (World Precision Instruments Inc., Sarasota, FL). Vitals, including heart- and breath-rate, were monitored via pulse oximetry (MouseOx, Starr Life Sciences Corp., Oakmont, PA). Prior to sterile surgery, mice were administered carprofen (5mg/kg, subcutaneous) and dexamethasone (2mg/kg, intramuscular) for anti-inflammation and restriction of edema after skull removal, respectively. Surgical instruments and artificial cerebral spinal fluid (ACSF, buffered pH 7.4) exposed to incision area were sterilized via autoclave. The mouse was placed supine and the head fixed to a stereotaxic frame (Narishige Scientific Instrument Lab, Tokyo, Japan). The scalp was shaved and resected to expose skull between bregma and lambda skull sutures. A 2-3 millimeter diameter portion of skull was removed with a dental drill (Ideal Microdrill, 0.8mm burr, Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA) with frequent ACSF perfusion. Cyanoacrylate (Vetbond, 3M, St. Paul, MN) was added to exposed skull areas to facilitate dental cement adhesion. A 5-8mm round coverglass (#1.5) was then placed with a layer of ACSF over the exposed brain. The dental cement mixture was wicked around the perimeter of the cover slip and sealed to surrounding skull, while retaining gentle pressure on coverslip to keep an air-tight seal for sterility and to restore intra-cranial pressure. A layer of cyanoacrylate was applied over the dental cement as well to fill porous regions and further seal the cranial window. Animals were allowed to recover from anesthesia and were monitored for cranial window integrity and behavior normality for at least two weeks before imaging.

2.5 Experiment conduction

1. Mice were anesthetized with 1.5-2% vaporized isoflurane in N2/O2 (80/20) and remained under nosecone inhalation while in the stereotaxic frame. Vitals were monitored through pulse oximetry and arterial oxygen saturation levels were maintained at 98 ± 0.5%.

2. Preliminary imaging to identify a surface arteriole of interests was conducted via LSCI. Cortical surface arterioles, also known as pial arterioles, eventually terminate in descending arterioles (Fig. 1(d)).

3. Two-photon imaging was commenced to obtain baseline measurements of oxygen tension and RBC velocities. FITC-dextran (0.1mL, 5% w-v, Sigma) and PtP-C343 (0.1mL, 2% w-v, target 6µM in plasma) were injected retro-orbitally to label the blood plasma and to serve as an oxygen sensor, respectively.

4. pO2 measurements were made iteratively from surface to deeper regions in the cortex in the descending arteriole. Five sequential lifetime acquisitions were made at each measurement location and averaged to account for any variability.

5. After baseline measurements, targeted occlusion of the arteriole of interest was performed upstream of cortical penetration. Real-time LSCI monitoring between 5 and 50ms of exposure within the targeted vessel provided feedback on the severity and spatial extent of the occlusions. The longer camera exposures register speckle contrast changes that are more sensitive to slower flows [28].

6. Subsequently, 2PLM was repeated after occlusion. Additional surface LSCI and two-photon linescans were used to confirm clot retention after post-occlusion pO2 measurements were concluded.

3. Results

3.1 Baseline pO2 in descending arterioles

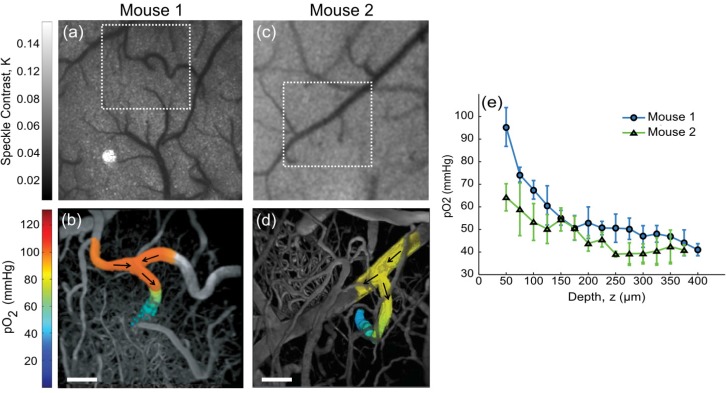

Baseline (e.g. no induced flow alteration) pO2 gradients in descending arterioles under normoxic conditions are presented in two mice (Fig. 3). Initially, laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) was performed to find regions containing descending arterioles of interest (Figs. 3(a) and 3(c)). Transverse vessel end points signify penetrating or ascending vessel segments. Branching order and relative flow strengths may be rapidly inferred from LSCI, while flow directions from two photon linescans can confirm arteriole and venule identities.

Fig. 3.

Speckle contrast images of cortical flow from Mouse 1 (a) and Mouse 2 (c). Baseline pO2 in descending arterioles. Projections of three-dimensional vascular imaging to a depth of 400 µm (b) and 375 µm (d) with pO2 measurements taken in the arterioles of Mouse 1 and 2, respectively. Arrows indicate flow direction. Scale bar = 50 µm. See Media 3 (22.2MB, MOV) for three-dimensional views of Mouse 1. (e) Baseline pO2 depth profile in descending arterioles from (b) and (d). First measurements (z = 50 µm) correspond to initial descent points. Data and error bars represent avg +/− s.d. over five measurements.

Over the length scales shown (Figs. 3(b) and 3(d)), surface intravascular levels of oxygen tension measured at several points remain within 5%. Substantial pO2 gradients are first observed with arteriole descent into the cortex. In Figs. 3(a)-3(b), the two surface arterioles flow into a single arteriole that subsequently descends into the cortical layers (see arrows, Fig. 3(b)). The second animal’s descending arteriole in Figs. 3(c) and 3(d) is fed by a single pial arteriole, which is the predominant branching paradigm observed off of the parent vessel. Both animals’ arterioles exhibit a 75% drop in oxygen tension within the first 150 µm of descent (Fig. 3(e)) despite the initial 30 mmHg surface pO2 disparity. The converging supply routes in Mouse 1 may account for the higher initial oxygen tension. A step size of 25 microns is used to sample these baseline gradients in relatively deep penetrating vessels, imaged with sufficient signal to background to nearly 400 µm (Media 3 (22.2MB, MOV) ). However, step sizes as small as one micron in depth may be achieved given the motorized objective assembly but come at the expense of temporal resolution and experiment duration. In particular, smaller steps are necessary for vessels exhibiting early networking or steeper gradients, especially those following targeted occlusions below.

3.2 pO2 after targeted-occlusion

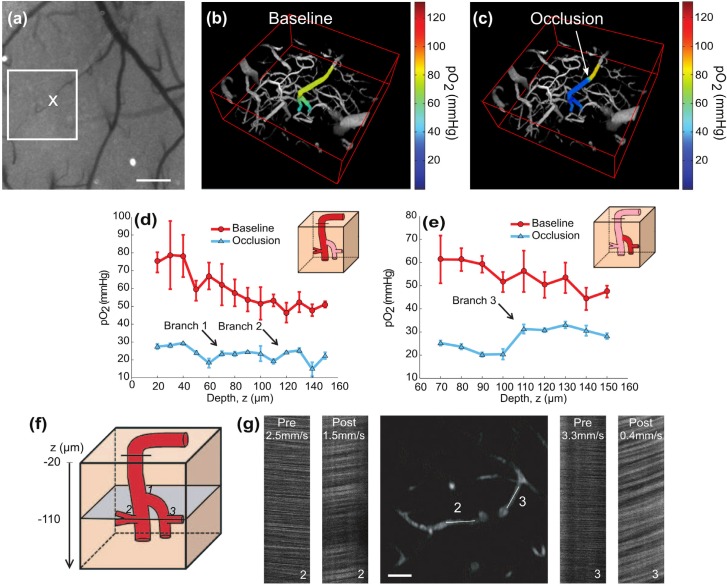

Observation 1: branching mediated pO2 distributions

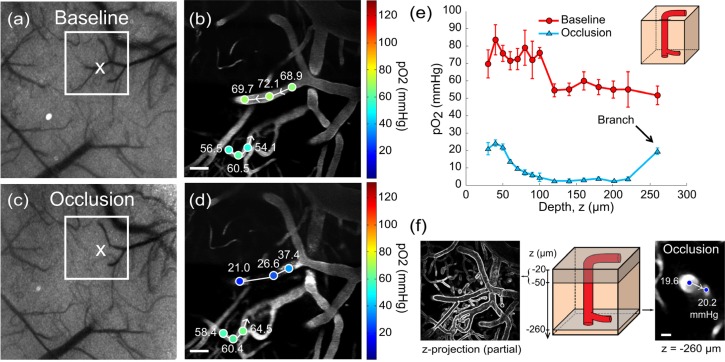

Again, LSCI provided a wide-field image of surface blood flow enabling quick targeting of a vascular region terminating in a descending arteriole, as seen in Fig. 4(a). Preliminary oxygen tension measurements were made in large portions of the surface and descending segments of the arteriole (Fig. 4(b) and Media 4 (33.3MB, MOV) ). An occlusion was made by photothrombotic clotting of the entire lumen in the surface segment of the vessel (Figs. 4(a) and 4(c)) and confirmed with two-photon linescans across the occlusion from upstream to downstream (Media 6 (549.5KB, PDF) ). Post-occlusion pO2 measurements were performed in the same vessel down to a depth of 150µm (Fig. 4(c) and Media 5 (39.2MB, MOV) ).

Fig. 4.

Targeted occlusion of an arteriole and resulting changes in oxygen tension and blood flow. (a) Baseline speckle contrast image. Two-photon imaging region is boxed and 'X' denotes photothrombosis location. Scale bar = 200 µm. (b) Baseline (Media 4 (33.3MB, MOV) ) and (c) post-occlusion (Media 5 (39.2MB, MOV) ) pO2 maps in descending arteriole. pO2 gradient downstream of occlusion significantly differs with baseline (p<002, repeated measures ANOVA). See Media 6 (549.5KB, PDF) for selected pial measurements and linescans. pO2 depth profile under baseline and post-occlusion conditions in the (d) primary descending arteriole and in a (e) secondary descending segment. Arrows denote branch points. Error bars represent avg +/− s.d. over five measurements. (f) Cartoon depicting branch points from (d) and (e) and imaging plane selection at a depth of 110 µm for (g) two-photon image and linescans in the enumerated branches. Scale bar = 25 µm.

Immediately upstream of the clot, intravascular pO2 remains consistent (90% confidence interval) with baseline measurements (Figs. 4(b)-4(c) and Media 6 (549.5KB, PDF) ). However, downstream there is a precipitous drop in pO2 (Fig. 4(c)) versus baseline measurements made over the same spatial regions (Fig. 4(b)), reaching absolute levels lower than that observed even in the deepest baseline measurement point (z = 150 µm, Fig. 4(d)). Given the low levels of post-occlusion pO2 in Fig. 4(d), the branch points with depth provide substantial pO2 elevations in the descent path. The primary arteriole branches into a second descending arteriole with comparable vessel caliber half way through the depth sampled and results in the first pO2 increment of 26% (Fig. 4(d), blue trace) after occlusion, followed by a second branch at z = 110 µm with another 26% increase in oxygen tension.

Before occlusion, both the primary and secondary descending arterioles have similar pO2 depth profiles (Figs. 4(d) and 4(e), p<0.001, ANOVA repeated measures). Two-photon linescans can provide both flow magnitude and perhaps more importantly direction to highlight flow redistributions in planar vessel segments. In Figs. 4(d)-4(g), a 31% (5 mmHg) increase in post-occlusion pO2 was observed in the primary arteriole at branch point ‘2’ and a 47% (10 mmHg) increase in the second descending arteriole at branch point ‘3′. Post-occlusion, flow reversal is observed in both branches with RBC speeds at 60% (branch point ‘2’) and 12% (branch point ‘3′) of baseline (Fig. 4(g)). The passive redistribution of flow through the branches does not scale directly with the relative pO2 increments at each branch point, highlighting that flow magnitudes alone may be poor indicators of relative oxygen supply when identifying bottlenecks and redundancy in the vascular architecture.

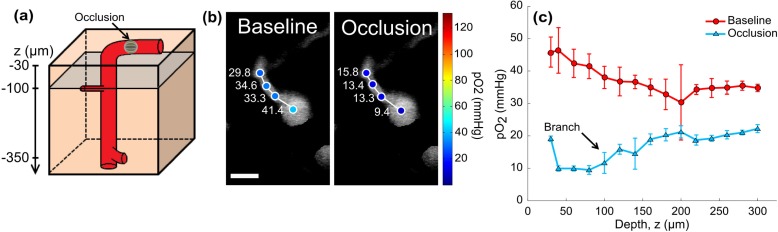

Observation 2: overlapping vessels and latent branching

Speckle imaging can be used to gauge the perfusion changes following an occlusion, particularly surrounding the arteriole of interest. The regional perfusion index is depth integrated and although does not provide the degree of vessel specificity of two-photon linescans, it is not limited to vessels flowing in the imaging plane formed by the lateral scan directions. In another mouse, baseline LSCI and two-photon imaging were performed to identify a pial arteriole leading to a descending segment for targeted occlusion in Figs. 5(a) and 5(c). It is difficult to estimate the O2 extraction by the underlying tissue given surface arterio-venous oxygen tensions alone in Figs. 5(b) and 5(d). This is partly due to the possibility of diffusional shunting between the large overlapping and neighboring vessels [9,10,29] in the more elevated planes seen in the speckle and two photon images as well as contributions from disparate underlying supply and drainage regions between the surface vessels. Ultimately, three dimensional mapping becomes necessary.

Fig. 5.

(a) Baseline and (c) post-occlusion LSCI; “X” marks location for targeted occlusion. (b) Baseline and (d) post-occlusion two-photon images and pO2 measurements in pial arteriole and venule. Arrows indicate flow direction. Scale bar = 50 µm. (e) pO2 depth profile in descending segment of pial arteriole in (a)-(d). Error bars represent avg +/− s.d. over five measurements. Baseline and occlusion pO2 gradients significantly differ (p<001, repeated measures ANOVA). (f) Partial z-projection with vascular outlines shows density of regional vasculature (left) and two photon image at z = 260 µm depicts branching point oxygen tensions (right). Cartoon (center) highlights projection depths and selected planes. Scale bar = 12 µm.

pO2 measurements were made in the descending arteriole down to its first branch seen in Fig. 5(e). The shallow baseline pO2 gradient seen in the first 80 microns of depth may be attributed to effects from the overlapping and neighboring vasculature seen in Fig. 5(f) as oxygen tensions remain within the relative measurement variability at each plane (see errorbars in Fig. 5(e)). Diffusional shunting across the vasculature can be noted with finer spatial sampling, as has been shown before using 2PLM [10]. After photothrombosis, a 70% drop in pO2 (post-/pre-occlusion) was observed in the surface segment of the descending arteriole in Fig. 5(d), followed by a low residual oxygen tension of 4 mmHg in the descending segment. Substantial branch-mediated elevation of oxygen tension is again apparent, though now observed much beneath the surface (19.6 ± 1.8 mmHg, z = 260µm, Figs. 5(e) and 5(f)). Measurements more distally into this branch also retained comparably elevated pO2 levels versus the descending arteriole (20.2 ± 2.4 mmHg in branch). Physiologically, the intravascular oxygen tensions may indicate extreme tissue hypoxia surrounding the vessel. Microcirculation studies observing substantial cell death in the cortical layers around single descending arterioles following occlusion may have sampled similar latent branching vessels [24,30]. The inherent sensitivity of the phosphorescent quenching oximetry technique noted in Figs. 1(c) and 1(e) is leveraged in mapping these residual intravascular oxygen tensions after occlusion.

Observation 3: gradient reversal in primary arteriole

Measurements of oxygen in a descending arteriole were made to a depth of 300µm in another animal, well beyond the first branch point noted in Fig. 6(a). As expected through the first branch, a decrease in pO2 away from the descending arteriole (Fig. 6(b) left) is observed consistent with blood supply exiting the primary vessel, though with insufficient fluorescence contrast to measure flow dynamics. However, this oxygen gradient is depressed if not reversed after occlusion, as pO2 levels no longer decrease in the branch more distal from the junction with the descending arteriole (Fig. 6(b) right). Additionally, the “u” shaped arteriolar gradient after occlusion shown in Fig. 6(c) may suggest flow reversal from downstream segments now supplying the main arteriole and exiting at the branch point.

Fig. 6.

(a) Depiction of a descending arteriole with plane of first branch shown in gray at a depth of approximately 85µm. (b) Two photon images showing baseline oxygen measurements in descending arteriole and first branch before and after occlusion corresponding to plane noted in (a). Reversal or depression of oxygen gradient away from primary arteriole is observed after occlusion. (c) pO2 depth profile in descending arteriole under baseline and post-occlusion conditions. Arrow indicates first pO2 measurement after branch at z = 85µm in depth. Error bars represent avg +/− s.d. over five measurements. Co-registered baseline and occlusion pO2 gradients significantly differ (p<002, repeated measures ANOVA).

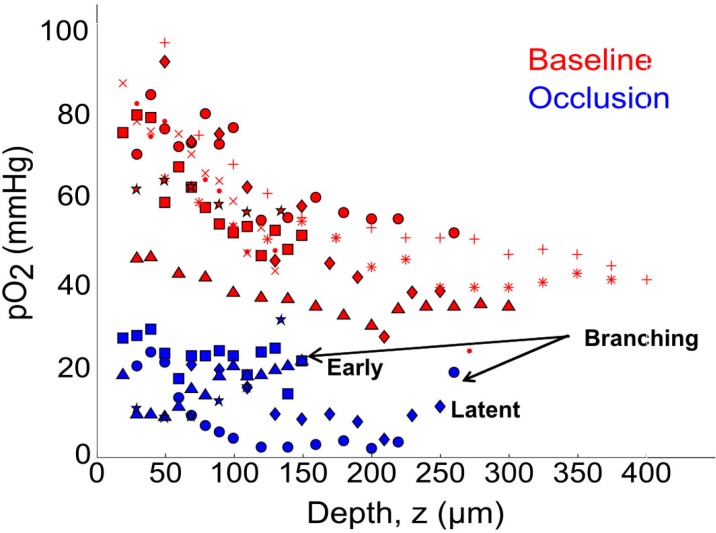

3.3 Observed pO2 gradient redistributions in summary

Our preliminary observations (Fig. 7, red symbols) register the majority of the arteriolar oxygen tension drop in depth within the first 150 µm of descent under baseline conditions (n = 9 arterioles across 8 animals) with no comparable drop in upstream surface segments over similar length scales. Beyond systemic pulse oximetry, oxygen tensions in two cortical arterioles were monitored for physiological variability (Media 7 (41.6KB, PDF) ), where repeated baseline depth profiles were observed to not significantly differ over comparable experiment durations to the occlusion studies. Chronic monitoring over multiple days may further elucidate any variability, while periodic systemic arterial blood gas analyses may be appropriate for acute settings. After occlusion (Fig. 7, blue symbols), no consistent pO2 depth profile seems retained and residual oxygen inflows varied with vascular architecture and were low in magnitude with respect to baseline. The effects of early (z ≤ 150 µm) and latent (z > 150 µm) branching after occlusion can be noted across animals in Fig. 7. This cursory depth classification of branching is juxtaposed to the steep baseline gradient observed in the elevated planes. In particular, the residual perfusion levels, oxygen tension maps, and vascular labeling as shown may be useful for examining the potential communicating roles of vessels within the regional microvascular network.

Fig. 7.

Partial pressure of O2 (pO2) depth profiles of descending arterioles under baseline (n = 9 vessels) and occlusion (n = 5 vessels) conditions across all animals. Symbols represent unique arterioles over 8 animals. “Early” branching is noted as occurring at z ≤ 150 µm, while “latent” occurring after this depth. See Media 7 (41.6KB, PDF) for repeated baseline measurements in two arterioles.

4. Discussion

Through the combination of two-photon fluorescence and phosphorescence lifetime microscopy with laser speckle contrast imaging and photothrombosis, we have presented an all-optical, non-contact system for interrogating oxygen tension and blood flow within the microcirculation. Specifically, we highlight the utility of using 2PLM for examining a large range of absolute oxygen tensions with three dimensional sectioning.

Our measurements were largely limited to single arterioles due to long acquisition times for occlusion studies which lead to the sparse sampling of vasculature. Acquisition times may be improved by increasing phosphorescent signal strength through higher intravascular concentrations of the oxygen probe and tuning the nonlinear excitation wavelength further into the near-infrared to take advantage of the probe’s improved two photon absorption cross-section [8]. This may also require use of more red-shifted vascular labeling fluorophores for structural contrast. Acquisition times may further be improved for more expansive lifetime measurements by recently reported frequency multiplexed implementations [31]. Additionally, current and emerging excitation sources for two-photon microscopy can provide sufficient signal to background for imaging to at least 700 µm beneath the dura mater [32–34]. This may be sufficient to reach most of the functionally relevant cortical layers of the mouse brain [5], but an assessment of the degree of out of plane signals will be necessary, as the sectioning ability may become coarser with deeper (z>400 µm) measurements in vivo.

Practically, photothrombosis and wide-field LSCI can be simple additions to existing two-photon lifetime microscopy systems using an available camera port and the ability to swap excitation and detection filters for the respective lasers. Rather than just the binary (e.g. flow or no flow) occlusion monitoring presented, speckle contrast images can be used for more quantitative registration with oxygen tensions by using dynamic light scattering models to convert the contrast values to estimates of the autocorrelation decay times of the speckles. These decay times more accurately decouple the flow-related contribution to the imaged speckles [14,35,36]. Finally, custom software coupling can enable seamless modality transitions as was done here within the C++ development environment.

4.1 Physiological perspectives

Ultimately, as the surface arterioles penetrate into the underlying cortex, several factors may contribute to the observed baseline oxygen depletion with depth: (1) the metabolic demand of the surrounding cortical tissue; (2) limited anastomosis in penetrating segments versus the surface [23]; (3) the change in the peri-vascular or blood-brain-barrier morphology [37]; and (4) changes in the vascularized fraction of the tissue sections with depth [38]. Further categorization by branch order, vessel size, and maximum depth of arteriole descent will be necessary before and after targeted occlusions. All these factors are measurable through labeled in vivo preparations followed by two-photon imaging as referenced. Particularly, 2PLM examination of the oxygen extraction in the resting and functionally activated brain will help corroborate previous findings of Clark electrode [2] and phosphorescence lifetime measurements made immediately outside the vascular lumen of cortical arterioles in small animals [12]. Perhaps more conclusively, this implementation can be used to bridge the findings of studies utilizing the more classical and invasive oximetry techniques for examining microvascular networking [2,39,40].

As presented, the combined optical technique can be used to highlight possible bottlenecks as well as redundancy and collateral supply by means of selective occlusions. Hemodynamic studies attempting to localize and quantify net oxygen extraction for interpreting cerebral metabolic rates [41] and fMRI signals [42] will benefit from selective and scalable flow alterations to decouple the effects of multiple vessels while obtaining flow-correlated intravascular oxygen tensions. The impact of reductions in intravascular oxygen tension on the metabolic health of the surrounding tissue may be obtained from two photon autofluorescence lifetime microscopy of NADH [43,44] as well as imaging of neuronal structural dynamics [45]. In order to further examine the functional layout of the microvascular network, occlusions and measurements may be scaled to increasing number of vessels. If expansive, the impact on cognitive function can be examined with the presence of molecular oxygen in the local microcirculation.

We have chosen cerebral microcirculation for demonstration due to its unique functional layout and relevance in neural activity through neurovascular coupling, which ultimately benefits from a non-contact hemodynamic characterization. Similar interrogations are not limited to the brain and may also be useful in other highly perfused systems provided the ability to establish optical access.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health (EB011556, NS078791), National Science Foundation (CBET-0644638) and the Coulter Foundation.

References and links

- 1.Tsai A. G., Johnson P. C., Intaglietta M., “Oxygen gradients in the microcirculation,” Physiol. Rev. 83(3), 933–963 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vovenko E., “Distribution of oxygen tension on the surface of arterioles, capillaries and venules of brain cortex and in tissue in normoxia: an experimental study on rats,” Pflugers Arch. 437(4), 617–623 (1999). 10.1007/s004240050825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang Q., Sakadžić S., Ruvinskaya L., Devor A., Dale A. M., Boas D. A., “Oxygen advection and diffusion in a three- dimensional vascular anatomical network,” Opt. Express 16(22), 17530–17541 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.017530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beard D. A., Bassingthwaighte J. B., “Modeling advection and diffusion of oxygen in complex vascular networks,” Ann. Biomed. Eng. 29(4), 298–310 (2001). 10.1114/1.1359450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shih A. Y., Driscoll J. D., Drew P. J., Nishimura N., Schaffer C. B., Kleinfeld D., “Two-photon microscopy as a tool to study blood flow and neurovascular coupling in the rodent brain,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 32(7), 1277–1309 (2012). 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estrada A. D., Ponticorvo A., Ford T. N., Dunn A. K., “Microvascular oxygen quantification using two-photon microscopy,” Opt. Lett. 33(10), 1038–1040 (2008). 10.1364/OL.33.001038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yaseen M. A., Srinivasan V. J., Sakadžić S., Wu W., Ruvinskaya S., Vinogradov S. A., Boas D. A., “Optical monitoring of oxygen tension in cortical microvessels with confocal microscopy,” Opt. Express 17(25), 22341–22350 (2009). 10.1364/OE.17.022341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finikova O. S., Lebedev A. Y., Aprelev A., Troxler T., Gao F., Garnacho C., Muro S., Hochstrasser R. M., Vinogradov S. A., “Oxygen microscopy by two-photon-excited phosphorescence,” ChemPhysChem 9(12), 1673–1679 (2008). 10.1002/cphc.200800296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakadžić S., Roussakis E., Yaseen M. A., Mandeville E. T., Srinivasan V. J., Arai K., Ruvinskaya S., Devor A., Lo E. H., Vinogradov S. A., Boas D. A., “Two-photon high-resolution measurement of partial pressure of oxygen in cerebral vasculature and tissue,” Nat. Methods 7(9), 755–759 (2010). 10.1038/nmeth.1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lecoq J., Parpaleix A., Roussakis E., Ducros M., Houssen Y. G., Vinogradov S. A., Charpak S., “Simultaneous two-photon imaging of oxygen and blood flow in deep cerebral vessels,” Nat. Med. 17(7), 893–898 (2011). 10.1038/nm.2394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parpaleix A., Houssen Y. G., Charpak S., “Imaging local neuronal activity by monitoring PO₂ transients in capillaries,” Nat. Med. 19(2), 241–246 (2013). 10.1038/nm.3059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devor A., Sakadžić S., Saisan P. A., Yaseen M. A., Roussakis E., Srinivasan V. J., Vinogradov S. A., Rosen B. R., Buxton R. B., Dale A. M., Boas D. A., “‘Overshoot’ of O₂ is required to maintain baseline tissue oxygenation at locations distal to blood vessels,” J. Neurosci. 31(38), 13676–13681 (2011). 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1968-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn A. K., “Laser speckle contrast imaging of cerebral blood flow,” Ann. Biomed. Eng. 40(2), 367–377 (2012). 10.1007/s10439-011-0469-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boas D. A., Dunn A. K., “Laser speckle contrast imaging in biomedical optics,” J. Biomed. Opt. 15(1), 011109 (2010). 10.1117/1.3285504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn A. K., Bolay H., Moskowitz M. A., Boas D. A., “Dynamic imaging of cerebral blood flow using laser speckle,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 21(3), 195–201 (2001). 10.1097/00004647-200103000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oheim M., Beaurepaire E., Chaigneau E., Mertz J., Charpak S., “Two-photon microscopy in brain tissue: parameters influencing the imaging depth,” J. Neurosci. Methods 111(1), 29–37 (2001). 10.1016/S0165-0270(01)00438-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lebedev A. Y., Troxler T., Vinogradov S. A., “Design of metalloporphyrin-based dendritic nanoprobes for two-photon microscopy of oxygen,” J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 12(12), 1261–1269 (2008). 10.1142/S1088424608000649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tom W. J., Ponticorvo A., Dunn A. K., “Efficient processing of laser speckle contrast images,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 27(12), 1728–1738 (2008). 10.1109/TMI.2008.925081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hossmann K. A., “Experimental models for the investigation of brain ischemia,” Cardiovasc. Res. 39(1), 106–120 (1998). 10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00075-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durukan A., Tatlisumak T., “Acute ischemic stroke: overview of major experimental rodent models, pathophysiology, and therapy of focal cerebral ischemia,” Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 87(1), 179–197 (2007). 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li P., Murphy T. H., “Two-photon imaging during prolonged middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice reveals recovery of dendritic structure after reperfusion,” J. Neurosci. 28(46), 11970–11979 (2008). 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3724-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armitage G. A., Todd K. G., Shuaib A., Winship I. R., “Laser speckle contrast imaging of collateral blood flow during acute ischemic stroke,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 30(8), 1432–1436 (2010). 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaffer C. B., Friedman B., Nishimura N., Schroeder L. F., Tsai P. S., Ebner F. F., Lyden P. D., Kleinfeld D., “Two-photon imaging of cortical surface microvessels reveals a robust redistribution in blood flow after vascular occlusion,” PLoS Biol. 4(2), e22 (2006). 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishimura N., Schaffer C. B., Friedman B., Lyden P. D., Kleinfeld D., “Penetrating arterioles are a bottleneck in the perfusion of neocortex,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104(1), 365–370 (2007). 10.1073/pnas.0609551104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klaassen C. D., “Pharmacokinetics of rose bengal in the rat, rabbit, dog and guinea pig,” Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 38(1), 85–100 (1976). 10.1016/0041-008X(76)90163-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson B. D., Dietrich W. D., Busto R., Wachtel M. S., Ginsberg M. D., “Induction of reproducible brain infarction by photochemically initiated thrombosis,” Ann. Neurol. 17(5), 497–504 (1985). 10.1002/ana.410170513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson C. A., Hatchell D. L., “Photodynamic retinal vascular thrombosis. Rate and duration of vascular occlusion,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 32(8), 2357–2365 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parthasarathy A. B., Kazmi S. M. S., Dunn A. K., “Quantitative imaging of ischemic stroke through thinned skull in mice with Multi Exposure Speckle Imaging,” Biomed. Opt. Express 1(1), 246–259 (2010). 10.1364/BOE.1.000246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kassissia I. G., Goresky C. A., Rose C. P., Schwab A. J., Simard A., Huet P. M., Bach G. G., “Tracer oxygen distribution is barrier-limited in the cerebral microcirculation,” Circ. Res. 77(6), 1201–1211 (1995). 10.1161/01.RES.77.6.1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shih A. Y., Blinder P., Tsai P. S., Friedman B., Stanley G., Lyden P. D., Kleinfeld D., “The smallest stroke: occlusion of one penetrating vessel leads to infarction and a cognitive deficit,” Nat. Neurosci. 16(1), 55–63 (2012). 10.1038/nn.3278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howard S. S., Straub A., Horton N. G., Kobat D., Xu C., “Frequency-multiplexed in vivo multiphoton phosphorescence lifetime microscopy,” Nat. Photonics 7(1), 33–37 (2012). 10.1038/nphoton.2012.307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobat D., Durst M. E., Nishimura N., Wong A. W., Schaffer C. B., Xu C., “Deep tissue multiphoton microscopy using longer wavelength excitation,” Opt. Express 17(16), 13354–13364 (2009). 10.1364/OE.17.013354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mittmann W., Wallace D. J., Czubayko U., Herb J. T., Schaefer A. T., Looger L. L., Denk W., Kerr J. N. D., “Two-photon calcium imaging of evoked activity from L5 somatosensory neurons in vivo,” Nat. Neurosci. 14(8), 1089–1093 (2011). 10.1038/nn.2879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horton N. G., Wang K., Kobat D., Clark C. G., Wise F. W., Schaffer C. B., Xu C., “In vivo three-photon microscopy of subcortical structures within an intact mouse brain,” Nat. Photonics 7(3), 205–209 (2013). 10.1038/nphoton.2012.336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strong A. J., Bezzina E. L., Anderson P. J. B., Boutelle M. G., Hopwood S. E., Dunn A. K., “Evaluation of laser speckle flowmetry for imaging cortical perfusion in experimental stroke studies: quantitation of perfusion and detection of peri-infarct depolarisations,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 26(5), 645–653 (2006). 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kazmi S. M. S., Parthasarthy A. B., Song N. E., Jones T. A., Dunn A. K., “Chronic imaging of cortical blood flow using Multi-Exposure Speckle Imaging,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 33(6), 798–808 (2013). 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCaslin A. F. H., Chen B. R., Radosevich A. J., Cauli B., Hillman E. M. C., “In vivo 3D morphology of astrocyte-vasculature interactions in the somatosensory cortex: implications for neurovascular coupling,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31(3), 795–806 (2011). 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsai P. S., Kaufhold J. P., Blinder P., Friedman B., Drew P. J., Karten H. J., Lyden P. D., Kleinfeld D., “Correlations of neuronal and microvascular densities in murine cortex revealed by direct counting and colocalization of nuclei and vessels,” J. Neurosci. 29(46), 14553–14570 (2009). 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3287-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duling B. R., Kuschinsky W., Wahl M., “Measurements of the perivascular PO2 in the vicinity of the pial vessels of the cat,” Pflugers Arch. 383(1), 29–34 (1979). 10.1007/BF00584471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ivanov K. P., Derry A. N., Vovenko E. P., Samoilov M. O., Semionov D. G., “Direct measurements of oxygen tension at the surface of arterioles, capillaries and venules of the cerebral cortex,” Pflugers Arch. 393(1), 118–120 (1982). 10.1007/BF00582403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yaseen M. A., Srinivasan V. J., Sakadžić S., Vinogradov S. A., Boas D. A., “Optically based quantification of absolute cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) with high spatial resolution in rodents,” Proc. SPIE 7548, 75483R–, 75483R-9. (2010). 10.1117/12.842904 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hermán P., Trübel H. K. F., Hyder F., “A multiparametric assessment of oxygen efflux from the brain,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 26(1), 79–91 (2006). 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yaseen M. A., Sakadžić S., Wu W., Becker W., Kasischke K. A., Boas D. A., “In vivo imaging of cerebral energy metabolism with two-photon fluorescence lifetime microscopy of NADH,” Biomed. Opt. Express 4(2), 307–321 (2013). 10.1364/BOE.4.000307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kasischke K. A., Lambert E. M., Panepento B., Sun A., Gelbard H. A., Burgess R. W., Foster T. H., Nedergaard M., “Two-photon NADH imaging exposes boundaries of oxygen diffusion in cortical vascular supply regions,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31(1), 68–81 (2011). 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang S., Murphy T. H., “Imaging the impact of cortical microcirculation on synaptic structure and sensory-evoked hemodynamic responses in vivo,” PLoS Biol. 5(5), e119 (2007). 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]