Abstract

Objective

Effective behavioral diabetes interventions for Mexican-Americans are needed. This manuscript documents the specific efforts to recruit Mexican-American adults for a trial testing a diabetes community health worker (CHW) self-management intervention. The unexpected limited yield of these efforts and lessons learned for recruitment in this population are discussed.

Design

Behavioral randomized controlled trial, community-based participatory research approach

Setting

Chicago

Participants

Mexican-American adults with type 2 diabetes

Outcome Measures

Screening and randomization

Methods

Initial eligibility criteria included Mexican heritage, treatment with oral diabetes medication, residence in designated zip codes, planned residence in the area for two years, and enrollment in a specific insurance plan.

Results

Recruitment through the insurer resulted in only one randomized participant. Eligibility criteria were relaxed and subsequent efforts included bilingual advertisements, presentations at churches and community events, postings in clinics, partnerships with community providers, and CHW outreach. Zip codes were expanded multiple times and insurance criteria removed. CHW outreach resulted in 53% of randomized participants.

Conclusions

Despite strong ties with the target community, culturally appropriate recruitment strategies involving community representation, and a large pool of potential participants, significant challenges were encountered in recruitment for this diabetes intervention trial. Researchers identified three key barriers to participation: study intensity and duration, lack of financial incentives, and challenges in establishing trust. For future research to be successful, investigators need to recognize these barriers, offer adequate incentives to compensate for intervention intensity, and establish strong trust through community partnerships and the incorporation of community members in the recruitment process.

Keywords: Diabetes, Community health workers, Mexican-American, Recruitment, Community-based participatory research, Behavioral randomized controlled trial

Introduction

Despite improvements in the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes, ethnic disparities in diabetes outcomes continue to widen. In 2007, 12.4% of Mexican-American adults had physician-diagnosed diabetes, which is twice as high as the rate for non-Hispanic whites.1 Mexican-American adults also had higher mortality from diabetes, along with greater rates of diabetic complications including end-stage renal disease and retinopathy.2–3 Culturally-sensitive interventions that target behavioral diabetes risk factors are needed to combat these disparities.

The implementation of interventions is slowed by challenges associated with enrolling racial/ethnic minority populations into randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Barriers include issues of trust, study time and effort, financial and language issues, and research team cultural competency.4–5 As a result of these barriers, direct targeting of Mexican-American adults into intervention research is limited and a standard effective recruitment method for this population does not exist.6–7 Current research and guidelines recommend a multimodal approach including: 1) Culturally appropriate strategies;4,8 2) Adequate time investment in community;9 3) Community engagement at the level of the health center, key personnel, and patients;8–11 4) Community trust;9–10,12 and 5) Involvement of community representatives and community health workers.12

The Mexican-American Trial of Community Health Workers (MATCH) incorporated these recommended methods into its recruitment plan. MATCH, funded by the National Institutes of Health, was a RCT testing the effectiveness of a community-based behavioral self-management intervention to reduce diabetes morbidity and mortality for Mexican-Americans. The study was set in Chicago, home to the nation’s fourth largest population of Mexican-Americans. Despite investigators’ strong ties with the target community, culturally appropriate recruitment strategies involving community representation, and a large pool of potential participants, significant recruitment challenges arose. This manuscript documents the specific efforts, their yield, and lessons learned in the recruitment of Mexican-American adults with type 2 diabetes for an intensive behavioral intervention trial.

Methods

MATCH Trial Details

The MATCH trial tested a 24-month diabetes self-management intervention delivered by CHWs. The trial was designed to have a large “dose” of the behavioral intervention in order to promote significant behavior change. After the baseline data collection and randomization, participants would receive either 36 mailed tip sheets or 36 home visits by community health workers (CHWs). CHWs are lay people from the target community who share language and cultural values with the target population. They receive specific training to educate and assist members of their community in gaining control over their health and lives.13 The CHW home visits provided self-management skills and diabetes information targeted to individual participant needs. The tip sheets were bilingual and covered a generic version of the diabetes and self-management curriculum delivered by the CHWs.

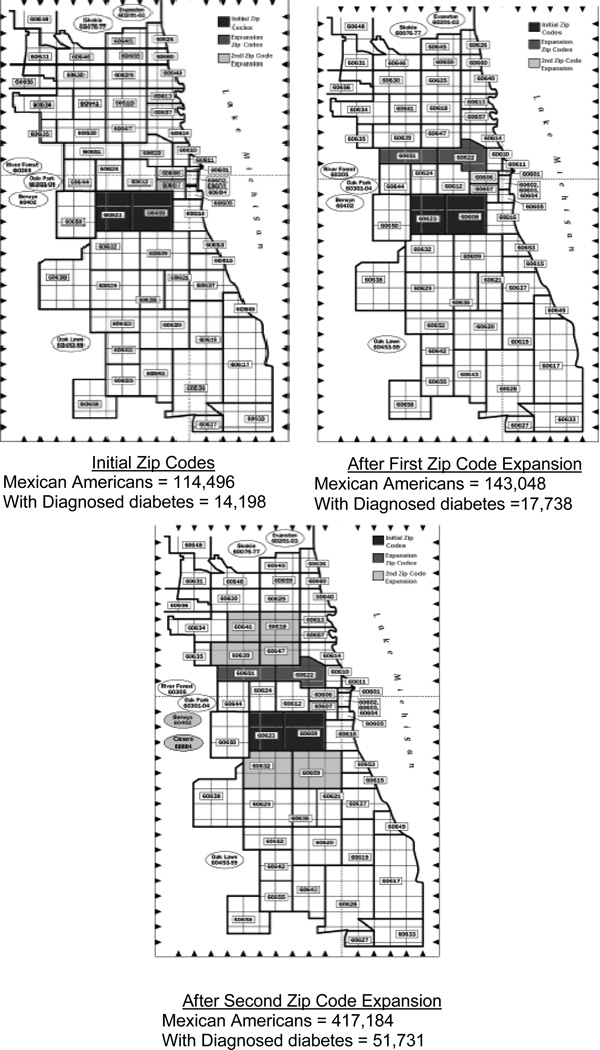

Initial study eligibility criteria included: 1) Mexican-American heritage, 2) type 2 diabetes, 3) treatment with oral diabetes medication, 4) residence in one of two zip codes, 5) planned residence in the area for two years, and 6) enrollment in a specific insurance plan. Two specific zip code areas were chosen because they contain a very high density of Mexican-Americans. Assuming a diabetes prevalence of 12.4%,1 the potential pool of participants in these zip codes was 14,198.14 The insurer was initially intended to be the primary recruitment source to ensure that all participants would have access to medications and glucose meters. Several insurers in the Chicago area were approached to participate in the study. One thought they had a sufficient number of clients to meet the study needs and agreed to perform the recruitment.

Data Collection

Screening for the study was performed by two bilingual bicultural research assistants. Due to HIPAA regulations, study research assistants were not able to use the insurance company rosters or clinic lists to directly contact potential participants. Instead, representatives from the insurer or clinics called potential participants who then had to contact the research assistants (usually by telephone) to be screened for eligibility. The research assistants noted all reasons for not passing the screener. They also asked about and documented the referral source for each participant.

Human Subjects Protection

This study was approved by the Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from participants at the time of enrollment.

Results (see Figures 1 and 2)

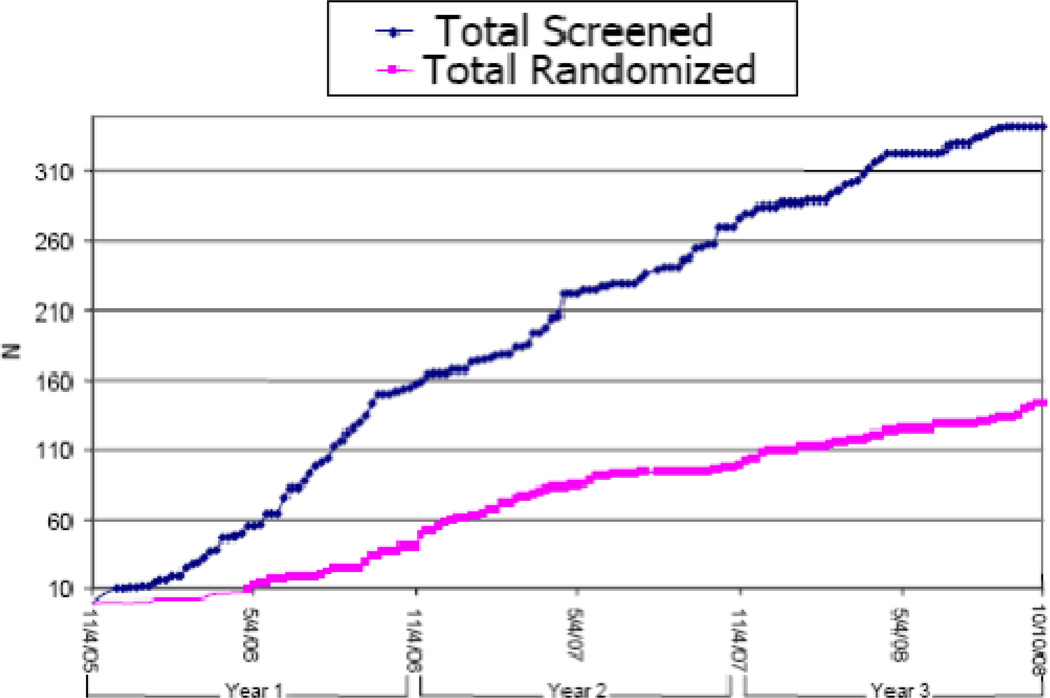

Figure 1.

Recruitment screening and randomization rates for the Mexican American Trial of Community Health (MATCH) Workers (Final: 343 screened, 144 randomized)

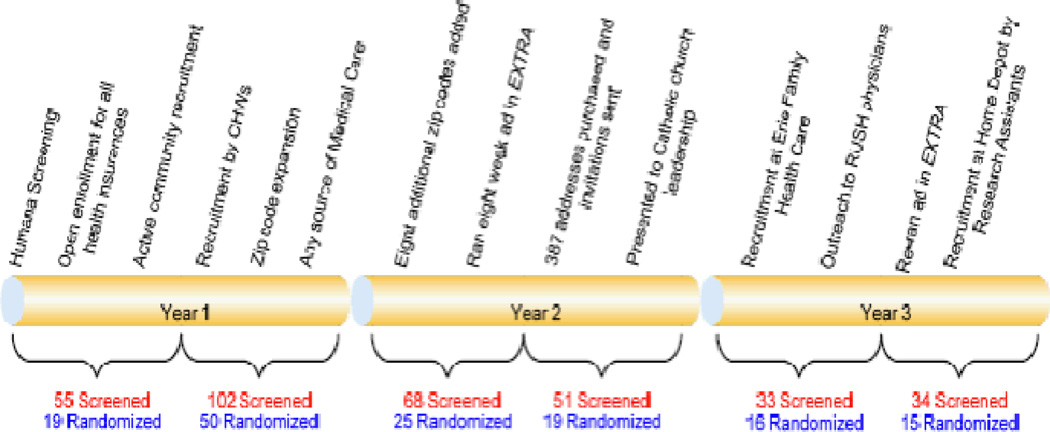

Figure 2.

Recruitment methods and associated results for the Mexican American Trial of Community Health (MATCH) Workers (Final: 343 screened, 144 randomized)

Recruitment methods implemented

Twelve months were allocated to complete recruitment of 144 participants. The insurer reported 259 Hispanic enrollees with diabetes, but after vigorous attempts by the insurance agency staff (up to 10 letters/phone calls per person reported), only one participant was randomized. At that point, the insurer-based recruitment plan was abandoned and a community-based recruitment plan implemented. This community-based plan incorporated all the recommended recruitment methods for Latino populations including the use of culturally appropriate strategies, adequate time investment for trust development, community engagement at multiple levels, and community health worker involvement.4,8–12

Knowledge of the community and the development of trust was the result of a long history of work and partnerships in this community. In 1988, the principal investigator (SKR) founded an academic practice in a storefront in this community which developed into a large successful practice. Over the past 15 years, the principal investigator has also implemented a wide range of partnerships with health and service agencies in this community which resulted in a substantial knowledge of community services, leaders, and norms. Another investigator (MAM) has volunteered for 10 years in this community where she has conducted research and service programs in partnership with local agencies.

Since trust was already established and community partnerships were in place, the first change in the recruitment strategy was to open recruitment to all types of insurance coverage to take advantage of these partnerships. Investigators and research assistants began to spread the message of the study throughout the target community by targeting all health related facilities and key personnel at these locations. Using primarily Spanish, they posted advertisements and made personal appearances at neighborhood clinics, service agencies, pharmacies, businesses, and churches. Bilingual tear-off fliers, discussions with staff, and information tables before and after church were used. Several local physician offices were offered financial compensation to review their records and call eligible patients. These offices expressed interest in the offer but did not generate any lists of potential participants.

CHWs did not participate in initial recruitment efforts because of their role as the primary interventionists. Additionally, there was concern that the CHWs’ belief in the value of their work would make it difficult for them to recruit people into a study with a control intervention. Ten months after the start of recruitment, the CHWs asked investigators if they could help in recruitment. They agreed to provide no promise of their services. The CHWs, well known in the community, used their community connections to facilitate recruitment. They gave presentations at neighborhood clinics, agencies, and residence homes. They also sought out individuals in clinics and the Mexican consulate. Investigators simultaneously relaxed two main inclusion criteria: eligible zip codes were expanded outward (see Figure 3), and patients who were not insured but had reliable access to medications through their clinic were included.

Figure 3.

Recruitment zip codes and potential participant numbers*

The investigators, research assistants, and CHWs continued to attend local events, clinics, agencies, churches, and businesses to promote the study during the second year. Zip codes were expanded again (see Figure 3). Marketing methods—specifically ads in a Spanish-language newspaper and direct mailings using a commercially-purchased list—were implemented. Participants were asked to refer friends and family members.

In the third year, outreach efforts in the community continued. The investigators strengthened a partnership with a well-respected community clinic by formally going through the clinic’s research board and establishing a financial contract. Clinic staff was paid to call their patients to invite study participation. If their patients were interested, the call was transferred directly to the research assistant or the research assistant’s contact information was given. Recruitment was completed in thirty-eight months.

Success of various methods (Table 1)

Table 1.

Recruitment sources for the Mexican American Trial of Community Health Workers (MATCH)

| Source | Screened N |

Randomized N |

% of total randomized |

% randomized from each source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advertisement | 35 | 12 | 8% | 34% |

| Church/Community Center | 12 | 5 | 3.5% | 42% |

| Community Event | 31 | 7 | 5% | 23% |

| Friend/Family | 20 | 11 | 8% | 55% |

| Medical Provider | 31 | 13 | 9% | 42% |

| Community Health Workers | 146 | 77 | 53.5% | 53% |

| Other* | 68 | 19 | 13% | 28% |

| Total | 343 | 144 | 100% | 42% |

Includes those who have not heard of MATCH, have heard of MATCH but did not list how they heard, and who listed their source as other

The largest number of participants was obtained through CHW outreach. They referred 146 potential participants, with 77 subsequently randomized. The next largest number of participants said they didn’t know how they heard about the study. Some participants (31 screened, 13 randomized) came from medical provider/clinic referrals which included referrals from the community clinic partnership that was developed in the third year. Additional referrals came from advertisements and family/friends. Very few participants came from community events and church/community centers despite many efforts to recruit from these sources.

Discussion

Despite the implementation of a multimodal community-based recruitment plan and a large potential pool of participants, recruitment for this diabetes trial was significantly more difficult than expected. The main challenge was identifying potential participants interested in being screened. From discussion with the research assistants, CHWs, and community representatives, investigators identified three key barriers which likely contributed the most to this challenge: study intensity and duration, lack of financial incentives, and challenges in establishing trust with potential participants.

This intervention is more intensive than most described in the previous studies of Latino recruitment methods: it entailed a two-year intervention period and 36 intervention points. Because travel for long periods of time would compromise data collection and intervention dose, potential participants were excluded if they anticipated being out of the country for more than four months a year. When describing the study to potential participants, investigators and staff noted that the study intensity and duration often seemed intimidating. Additionally, lack of certainty regarding travel plans was a barrier to participation for many individuals.

Investigators chose not to provide financial incentives because they wanted to test the intervention in real-world conditions. They also assumed that people would view the study services offered as valuable. Over time, investigators gained appreciation for the time pressures felt by participants and realized that compensation, at least for the data collection visits, would have improved participation.

Despite linguistic and cultural competence and a long history of engagement with the target community, the investigators and research assistants did not easily establish trust with potential participants. The sponsoring hospital was unfamiliar to most participants. Investigators were informed by a neutral community liaison that some community clinics feared the academic center would try to steal their patients. Additionally, by presenting the study at almost every clinical and service agency in the target community, investigators committed long hours to canvassing widely, rather than allocating that time towards the development of fewer, more-focused and trusted partnerships with agencies and community-based organizations. Once a strong partnership was formed with a well-respected community clinic, recruitment efforts improved because the patients of the clinic trusted their clinic’s recommendation to participate and the clinic trusted the academic center to respect their practice. This is similar to the experience of Davis et al. in rural communities.10

The CHWs provided additional evidence of the importance of generating trust. They excelled at recruitment because they were familiar trusted faces in the community and because they spent a lot of time with community agencies and people, much more so than the investigators and research assistants. The CHWs had both ascribed and achieved credibility in their community, while investigators and researchers had only ascribed credibility. Ascribed credibility typically includes education, experience, and ethnicity—basically the individual’s initial judgment or expectations based on status. Achieved credibility, however, takes time. It includes gaining the individual’s trust based on actual performance or competency, including perceived cultural knowledge and awareness, and use of skills that are culturally sensitive.15

Overall, 42% of those screened were randomized into the MATCH trial. This was a good screening-to-randomization ratio taking into consideration the lack of financial incentives and time commitment involved in MATCH. The intensity of a trial can be a barrier to recruitment. While other trials with Latinos have reported higher screening-to-recruitment ratios,11, 16–17 we believe the lower intensity of the interventions was a significant factor in their higher recruitment rates.18 Different racial/ethnic groups also respond differently to recruitment efforts.6 For MATCH, once people agreed to be screened, a significant barrier had already been overcome. The people who participated in screening were interested and motivated despite cultural issues, trust barriers, and time commitments. This was likely because the majority of those screened were initially approached by CHWs or their medical providers.

Another method in our study that yielded different results than in other studies was the community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach. The use of a strong CBPR approach for recruitment into a cancer trial resulted in a large sample of low-income Latinos for Larkey et al.12 In the recruitment of Latino patients for other cancer trials, Sheppard et al. reported that the inclusion of multicultural staff, use of the Latino media, incorporation of social networks, use of spokespersons, and culturally tailored messages resulted in a 96% participation rate of those eligible.4 We incorporated these elements but with much less success. A review of three other cancer studies showed recruitment results more consistent with ours, despite their incorporation of culturally-relevant messages, community member referral networks, and awareness of community realities.8

Implications for Future Research

Intensive behavioral interventions for Latino populations are needed to reduce the impact of type 2 diabetes in this growing population. The experiences in the MATCH trial provide several new considerations for future endeavors. Because of the tremendous variation among Latino populations and reactions to different interventions, recruitment plans should be determined de novo for each study. However, behavioral intervention research in Mexican-American populations should take into account the following:

Avoid optimistic projections of participation. Make eligibility criteria as broad as possible from the start in order to screen a large number of potential participants.

Avoid optimistic projections of participation. Make eligibility criteria as broad as possible from the start in order to screen a large number of potential participants.

An intensive exploration of motivators and barriers to participation should be assessed before the start of recruitment.9,19 Qualitative methods such as focus groups and key informant interviews can be useful to obtain this information.

Plan to engage the target community early and through multiple approaches.8–9,19

Invest the time to cultivate a few strong, mutually-beneficial partnerships with highly committed, well respected agencies.11

Recruiters with language competence may not be sufficient to gain confidence with vulnerable immigrant populations. CHWs or other trusted neighbors can be more effective.

Acknowledgments

The Mexican American Trial of Community Health Workers is funded by grant number R01 DK061289 from The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) at the National Institutes of Health. The design, development, and implementation of the MATCH study, and the work described in this paper, would not have been possible without the efforts of promotoras Pilar Gonzalez, Susana Leon, Maria Sanchez, and the staff of Centro San Bonifacio. Estamos agradecidos.

References

- 1.Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Adults: 2007, Table 8, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed 18 January 2010];2009 Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_240.pdf.

- 2.Age-Adjusted Percentage of Adults with Diabetes Reporting Visual Impairment by Race/Ethnicity, United States, 1997–2007; Centers for Disease Health Interview Survey; 2009. [Accessed 18 January 2010]; Available from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/visual/dtltable5.htm.

- 3.Age-Adjusted Incidence of End-Stage Renal Disease Related to Diabetes Mellitus (ESRD-DM) per 100,000 Diabetic Population, by Race/Ethnicity and Sex, United States, 1980–2006; United States Renal Data System. [Accessed 18 January 2010];National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009 Available from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/esrd/Fig5Detl.htm.

- 4.Sheppard VB, Cox LS, Kanamori MJ, et al. Brief report: if you build it, they will come: methods for recruiting Latinos into cancer research. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:444–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med. 2006;3:e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Khorazaty MN, Johnson AA, Kiely M, et al. Recruitment and retention of low-income minority women in a behavioral intervention to reduce smoking, depression, and intimate partner violence during pregnancy. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:233. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le HN, Lara MA, Perry DF. Recruiting Latino women in the U.S. and women in Mexico in postpartum depression prevention research. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11:159–169. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larkey LK, Ogden SL, Tenorio S, Ewell T. Latino recruitment to cancer prevention/screening trials in the Southwest: setting a research agenda. Appl Nurs Res. 2008;21:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NHLBI. Working Group. Bethesda, MD: Summary and Recommendations. NHLBI; 2003. Jul-Aug. [Accessed 25 March 2009]. Epidemiologic Research in Hispanic Populations. Opportunities, Barriers and Solutions. Available from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/meetings/workshops/hispanic.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis RM, Hitch AD, Nichols M, Rizvi A, Salaam M, Mayer-Davis EJ. A collaborative approach to the recruitment and retention of minority patients with diabetes in rural community health centers. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eakin EG, Bull SS, Riley K, Reeves MM, Gutierrez S, McLaughlin P. Recruitment and retention of Latinos in a primary care-based physical activity and diet trial: The Resources for Health study. Health Educ Res. 2007;22:361–371. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larkey LK, Gonzales JA, Mar LE, Glantz N. Latina recruitment for cancer prevention education via Community Based Participatory Research strategies. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witmer A, Seifer SD, Finocchio L, Leslie J, O'Neil EH. Community health workers: integral members of the health care work force. Am J Pub Health. 1995;85(8):1055–1058. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.8_pt_1.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Census Bureau. Census 2000. [Accessed 10 July 2009]; Available at http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DatasetMainPageServlet?_program=DEC&_submenu1d=&_lang=en&_ts=.

- 15.Sue S. Cultural competency: From philosophy to research and practice. J Community Psychol. 2006;34:237–245. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramos-Gomez F, Chung LH, Gonzalez Beristain R, et al. Recruiting and retaining pregnant women from a community health center at the US-Mexico border for the Mothers and Youth Access clinical trial. Clin Trials. 2008;5(4):336–346. doi: 10.1177/1740774508093980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joseph G, Kaplan CP, Pasick RJ. Recruiting low-income healthy women to research: an exploratory study. Ethn Health. 2007 Nov 12;(5):497–519. doi: 10.1080/13557850701616961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oddone EZ, Olsen MK, Lindquist JH, et al. Enrollment in clinical trials according to patients race: experience from the VA Cooperative Studies Program (1975–2000) Control Clin Trials. 2004 Aug 25;(4):378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marín G, Marín B. Research with Hispanic Populations. Applied Social Research Methods Series, v23. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1991. pp. 38–39. [Google Scholar]