Abstract

PURPOSE

Whether patients with 1 or more chronic illnesses are more or less likely to receive recommended preventive services is unclear and an important public health and health care system issue. We addressed this issue in a large national practice-based research network (PBRN) that maintains a longitudinal database derived from electronic health records.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional study as of October 1, 2011, of the association between being up to date with 10 preventive services and the prevalence of 24 chronic illnesses among 667,379 active patients aged 18 years or older in 148 member practices in a national PBRN. We used generalized linear mixed models to assess for the association of being up to date with each preventive service as a function of the patient’s number of chronic conditions, adjusted for patient age and encounter frequency.

RESULTS

Of the patients 65.4% had at least 1 of the 24 chronic illnesses. For 9 of the 10 preventive services there were strong associations between the odds of being up to date and the presence of chronic illness, even after adjustment for visit frequency and patient age. Odds ratios increased with the number of chronic conditions for 5 of the preventive services.

CONCLUSIONS

Rather than a barrier, the presence of chronic illness was positively associated with receipt of recommended preventive services in this large national PBRN. This finding supports the notion that modern primary care practice can effectively deliver preventive services to the growing number of patients with multiple chronic illnesses.

Keywords: preventive health services, chronic disease, primary health care, comorbidity

INTRODUCTION

It has long been argued that competing demands in the primary care encounter are barriers to the effective delivery of clinical preventive services.1 One estimate is that 7.4 hours of a primary care clinician’s workday would be needed to provide services recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF),2 clearly impossible given competing demands for acute care, chronic care, and other responsibilities.

An alternative perspective is that encounters primarily for other reasons, particularly for chronic illnesses that entail frequent clinician contacts, would facilitate delivery of clinical preventive services. Research to date on this issue has yielded inconsistent findings. A 1997 study showed that patients with chronic illness were less likely to receive recommended preventive services,3 as did a more recent report focused only on patients with diabetes mellitus.4 In contrast, other reports have shown positive associations between chronic disease comorbidity and osteoporosis screening,5 and between rheumatoid arthritis and dyslipidemia and osteoporosis screening.6

All existing reports are limited by the number of practices, patients, preventive services, and chronic illnesses analyzed. In this report, we analyze the cross-sectional association between receipt of 10 preventive services recommended by the USPSTF and the prevalence of 24 chronic illnesses among 667,379 active patients aged 18 years or older in 148 practices affiliated with a national primary care practice-based research network (PBRN).

METHODS

The study was conducted in PPRNet, a PBRN founded in 1995,7 which now comprises 233 practices in 43 states. Unique among US PBRNs is the PPRNet database, which is derived from the Practice Partner electronic health record (EHR) (McKesson Corporation) used in each participating practice. The longitudinal database contains anonymized demographic and clinical data and is updated quarterly through automated data extracts.

For this report, we used the PPRNet database updated as of October 1, 2011. Practices that had begun to use Practice Partner on or after January 1, 2010, were excluded from the analyses to better assure adequate time for recording of chronic illnesses and delivery or recording of prior preventive services. Practices whose primary specialty was not family practice or general internal medicine or those with fewer than 100 active patients aged at least 18 years were also excluded. Patients were defined as active in the practice if there was a progress note recorded in the EHR within 1 year of October 1, 2011.

Demographics, problems, diagnoses, procedures, vital signs, preventive services, laboratory results, and progress note titles recorded in the EHR from active patients were included in the analyses. Data from problem and diagnoses lists were used to assess the prevalence of the chronic conditions; all data elements were used to assess receipt of preventive services. Because the EHR allows free-text data entry, PPRNet uses computer algorithms for pattern matching and expert review to assign International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes to diagnoses, Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) for laboratory data, and an internal dictionary for other data elements. From audits conducted in the early phases of these analyses for the chronic conditions included in this report, we have determined that, compared with review by a clinician, our approach has at least 99% sensitivity and 99% specificity for identification of these diagnoses.

The preventive services studied are all grade A or B screening recommendations of the USPSTF: screening for high blood pressure, lipid disorders, cervical cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, urogenital chlamydial infection, type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults with elevated blood pressure, alcohol misuse, depression, and osteoporosis.8 The 24 chronic conditions studied represent a broad spectrum of illnesses relevant to primary care practice and are conditions of priority for comparative effectiveness research.9,10

The proportion of patients up to date with a given preventive service was calculated by dividing the number of patients who had received the service in the recommended interval by the number of patients eligible for the service. The prevalence for each chronic condition studied was calculated by dividing the number of patients with the condition by the number of active patients. The total number of chronic conditions (of the 24 studied) was also determined for each patient. Encounter frequency was defined for each patient as the number of progress notes between October 1, 2010, and September 30, 2011.

For each preventive service, we first calculated the unadjusted percentages of eligible patients who were up to date for those with 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 or more chronic illnesses. We then used generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs)11 to model the up-to-date status with the preventive service (yes/no) as a function of the patient’s number of chronic conditions, treating number of chronic conditions as a categorical variable with 6 categories (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ≥5). All GLMMs incorporated logit link functions and accounted for clustering of patients within practices by means of random practice effects with compound symmetry error structures. In essence, the GLMMs served as hierarchical logistic regression models. Models for each preventive service were constructed with covariate adjustment for patient age and encounter frequency. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were computed and reported.

RESULTS

One hundred seventy-two practices provided data as of October 1, 2011. Eight practices that had begun comprehensive use of Practice Partner on or after January 1, 2010, were excluded, as were 11 whose primary specialty was not family practice or general internal medicine, and 5 because they had fewer than 100 active adult patients. One hundred forty-eight practices with 667,379 active adult patients remained in the analytic data set. Specialty distribution among the 148 practices was 77.0% family practice, 16.2% internal medicine, and 6.8% combinations of primary care specialists and other physicians. Among the patients, 58.2% were female and 41.7% were male; sex was not recorded in 0.1% of the patients. The age distribution was as follows: 18 to 34 years 23.8%, 35 to 44 years 15.9%, 45 to 54 years 19.4%, 55 to 64 years 18.8%, 65 to 74 years 12.1%, 75 to 84 years 7.0%, and 85 or more years 3.0%.

Table 1 lists the 24 chronic conditions and the prevalence of each diagnosis as of October 1, 2011. Hyperlipidemia and hypertension were the most prevalent diagnoses, each affecting one-third of the patients. Among the 667,379 active patients, the proportion with 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 or more chronic conditions was 34.6%, 20.1%, 14.9%, 11.2%, 7.7%, and 11.5%, respectively.

Table 1.

Chronic Conditions Prevalence Among 667,379 Active Patients in 148 Practices as of October 1, 2011, in Order of Frequency

| Chronic Condition | No. With Condition | % With Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 223,653 | 33.51 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 220,053 | 32.97 |

| Depression | 124,596 | 18.67 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 99,658 | 14.93 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 79,641 | 11.93 |

| Obesity | 79,407 | 11.90 |

| Osteoarthritis | 66,255 | 9.93 |

| Asthma | 58,900 | 8.73 |

| Osteoporosis and osteopenia | 43,700 | 6.55 |

| Migraine | 37,756 | 5.66 |

| Coronary disease | 32,867 | 4.92 |

| Atherosclerosis | 31,638 | 4.74 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 29,005 | 4.35 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 22,496 | 3.37 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 19,227 | 2.88 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 14,487 | 2.17 |

| Heart failure | 11,241 | 1.68 |

| Alcohol use disorders | 8,594 | 1.29 |

| Dementia | 7,361 | 1.10 |

| Peptic ulcer | 7,242 | 1.09 |

| Chronic liver disease | 6,951 | 1.04 |

| Epilepsy | 6,893 | 1.03 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 6,357 | 0.95 |

| Parkinson’s disease or syndrome | 1,886 | 0.28 |

Table 2 displays the 10 preventive services, the relevant time and demographic parameters for each, the number of eligible patients, and percentage up to date. Almost all eligible patients had a blood pressure recorded in their EHR. Three-quarters were up to date with glucose screening for elevated blood pressure and with cholesterol screening. About one-half of eligible patients were current with mammography screening and bone mineral density screening, and just over two-fifths with any form of colorectal cancer screening or Papanicolaou smears for cervical cancer screening. Only 1 in 5 had recorded screening for depression or at-risk drinking, and 1 in 6 for screening for urogenital chlamydial infection.

Table 2.

Grade A and B Recommendations of US Public Service Task Force Studied, Eligible Patients for Each Service, and Percentage Up to Date as of October 1, 2011

| Preventive Service | Interval y | Age y | Sex | No. of Eligible Patients | Up to Date % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure measurement | 2 | ≥18 | Both | 667,379 | 96.80 |

| At-risk drinking assessment | 2 | ≥18 | Both | 667,379 | 22.57 |

| Depression screen | 2 | ≥18 | Both | 667,379 | 18.75 |

| Total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol | 5 | ≥35 | Male | 446,502 | 73.16 |

| ≥45 | Female | ||||

| Blood glucose measurement if last blood pressure >135/80 mm Hg | 3 | ≥18 | Both | 348,084 | 76.10 |

| Colorectal cancer | a | 50–74 | Both | 274,716 | 43.71 |

| Papanicolaou smear | 3 | 21–64 | Females | 268,850 | 42.63 |

| Mammogram | 2 | 50–74 | Females | 150,452 | 52.95 |

| Bone density | Any | ≥65 | Females | 86,200 | 47.71 |

| Urogenital chlamydia | 1 | 18–24 | Females | 43,762 | 13.39 |

Colonoscopy within 10 years, sigmoidoscopy within 5 years, or fecal occult blood test within 1 year.

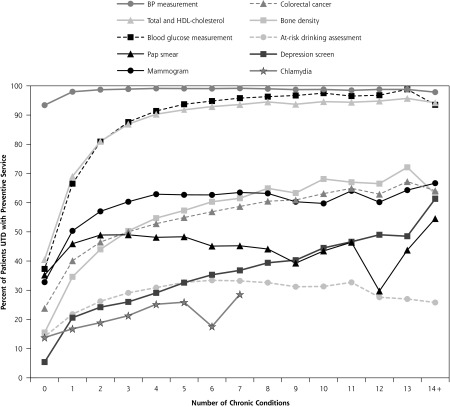

The unadjusted associations between being up to date with each preventive service and the number of chronic conditions are depicted in Figure 1. For each preventive service, there is a curvilinear relationship with the number of chronic conditions, with an increased likelihood of being up to date with a preventive service as the number of chronic conditions increases from 0 to 4 or 5. At that point, for the most part, the association plateaus, and there are no further increases in the proportion of patients up to date with the preventive service as the number of chronic conditions increases above 5. Blood pressure measurement is an exception to the pattern; it seems to plateau once there is at least 1 chronic condition.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted associations between being up to date with each preventive service and the number of chronic conditions.

BP = blood pressure; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; Pap = Papanicolaou; UTD = up to date.

Table 3 shows the association between being up to date with each of the preventive services and the number of chronic conditions, adjusted for patient age and encounter frequency. For each preventive service other than screening for urogenital chlamydia, there are strong associations between the odds of being up to date and the presence of chronic illness, even after adjustment for visit frequency and patient age. Adjusted odds ratios increase with the number of chronic conditions, most prominently for depression screening, but also for cholesterol, diabetes, colorectal cancer, and bone density screening.

Table 3.

Odds of Being Up to Date With Preventive Service Based on Number of Chronic Conditions Compared With Patients With No Chronic Conditions, Adjusted for Patient Age and Encounter Frequency

| Chronic Conditions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Preventive Service | 1 OR (95% CI) |

2 OR (95% CI) |

3 OR (95% CI) |

4 OR (95% CI) |

≥5 OR (95% CI) |

| Blood pressure measurement | 2.9 (2.8–3.0) | 4.4 (4.1–4.7) | 5.0 (4.6–5.4) | 5.7 (5.2–6.3) | 4.3 (3.9–4.6) |

| At-risk drinking assessment | 1.7 (1.7–1.8) | 2.3 (2.3–2.4) | 2.7 (2.7–2.8) | 2.9 (2.8–3.0) | 3.1 (3.0–3.2) |

| Depression screen | 6.3 (6.1–6.4) | 9.2 (8.9–9.4) | 11.7 (11.3–12.0) | 14.8 (14.4–15.4) | 21.8 (21.1–22.5) |

| Total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol | 3.1 (3.1–3.2) | 6.1 (6.0–6.3) | 9.4 (9.2–9.7) | 13.0 (12.5–13.5) | 16.2 (15.6–16.8) |

| Blood glucose measurement if last blood pressure >135/80 mm Hg | 2.6 (2.5–2.7) | 4.7 (4.6–4.9) | 6.7 (6.5–6.9) | 8.8 (8.4–9.2) | 11.1 (10.6–11.6) |

| Colorectal cancer | 1.9 (1.8–1.9) | 2.3 (2.2–2.3) | 2.5 (2.4–2.6) | 2.7 (2.6–2.7) | 2.9 (2.8–3.0) |

| Papanicolaou smear | 1.4 (1.3–1.4) | 1.5 (1.4–1.5) | 1.4 (1.4–1.4) | 1.3 (1.2–1.3) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) |

| Mammogram | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) | 2.2 (2.1–2.3) | 2.4 (2.3–2.5) | 2.5 (2.4–2.6) | 2.1 (2.1–2.2) |

| Bone density | 2.9 (2.7–3.1) | 4.0 (3.8–4.3) | 5.0 (4.6–5.3) | 5.8 (5.4–6.2) | 6.9 (6.4–7.3) |

| Urogenital chlamydia | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.5 (0.3–1.0) |

DISCUSSION

In this study of two-thirds of a million adult patients from 148 primary care practices across the United States, we have found strong positive associations between receipt of clinical preventive services and the presence of chronic illnesses. These associations persisted regardless of the number of chronic illnesses. This finding is in contrast to oft-expressed concerns that increasing patient complexity (defined as having more than 1 chronic illness) impedes the delivery of preventive services because of competing demands.1 Our findings persisted even after adjustment for age and encounter frequency, suggesting that it is something in the nature of the care provided to these patients that accounted for the finding of increased attention to prevention.

The explanation for our findings is unclear. Most PPRNet practices have attended PPRNet meetings and/or participated in PPRNet quality improvement research projects that emphasize the importance of evidence-based care, team care, and use of EHR decision support, such as preventive services reminders. PPRNet also provides quarterly clinical quality reports to member practices, which include practice-, provider-, and patient-level data on the preventive services studied, as well as other quality indicators for acute and chronic illness care. It could be that practices, using these reports as chronic illness registries, may have attended to preventive services in addition to the chronic illness when conducting outreach efforts to patients. Such outreach efforts might not be directed to patients without chronic illness. It could also be that care management activities inherent in encounters for chronic illness care, such as ordering tests and arranging follow-up, provide the context for provision of preventive services. Indeed, a direct observation study of primary care clinicians found that preventive services were delivered during 39% of visits for chronic illness.12

There are several potential limitations of our report. One is confounding by condition. For example, that the odds ratios for cholesterol and blood glucose measurement increased with the number of chronic conditions could be confounded by several of the most common chronic conditions, such as diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia, being themselves indications for these services. A subanalysis excluding the 79,641 patients with diabetes mellitus, however, did not alter the strong positive association between blood glucose measurement for elevated blood pressure and the number of chronic conditions. Excluding the 220,053 patients with hyperlipidemia attenuated but did not eliminate the association between screening for total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and patient complexity. That the odds of screening for depression, colorectal cancer, and bone mineral density also increased with the number of chronic conditions mitigates the possibility of confounding being responsible for most of the observed associations.

As in any secondary analysis, we could not independently validate our data sources, the diagnoses, and preventive services data in the EHRs of patients in the participating practices. A specific concern relevant to this limitation is the possibility of information bias, which might be present if practices or members of practices were both more diligent in recording chronic illnesses and receipt of a preventive service. It is unlikely that this potential bias was responsible for our study findings for 2 major reasons. First, the observed associations were strong, which would not have occurred unless most of the practices were affected by information bias, an unlikely occurrence. Second, the observed associations were present for 9 of the 10 preventive services, most of which are documented in ways other than direct entry, including automated downloading of laboratory and procedure results.

A final limitation is that, despite the relatively large, geographically diverse, sample of practices and clinicians included in this study, all were users of a single EHR and voluntary members of a PBRN. The extent to which the findings from this group of practices can be generalized across all primary care settings in the United States and other countries with similar health care systems is unknown. Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings support the notion that modern primary care practices, facilitated by tools like EHRs and joined in learning networks such as PBRNs, can overcome competing demands and effectively deliver preventive services to the growing number of patients with multiple chronic illnesses.13 Epidemiologic studies suggest that principles of the patient-centered medical home facilitate preventive services delivery.14,15 Empirical evidence points to the positive impact on preventive services delivery of EHR-based reminders and standing orders for nonclinician staff,16 as well as multicomponent interventions using audit and feedback, academic detailing, and practice facilitation.16,17 Whether these strategies have a similar impact among patients with multiple chronic illnesses is a subject for future research.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Jodie Riley for contributing to the data acquisition and Vanessa Congdon for contributing to the data analyses for this report.

Footnotes

Prior presentations: The work presented in this manuscript has not been previously presented.

Conflicts of interest: PPRNet/MUSC has a research and development contract with McKesson and Dr Ornstein is the principal investigator. Drs Jenkins and Wessell receive salary support from the contract. Drs Litvin and Nietert do not have any conflicts of interest to report.

Funding support: This study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Grant number 1R24HS019448.

References

- 1.Jaén CR, Stange KC, Nutting PA. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract. 1994;38(2):166–171 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Østbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):635–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fontana SA, Baumann LC, Helberg C, Love RR. The delivery of preventive services in primary care practices according to chronic disease status. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(7):1190–1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owens MD, Beckles GL, Ho KK, Gorrell P, Brady J, Kaftarian JS. Women with diagnosed diabetes across the life stages: underuse of recommended preventive care services. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(9):1415–1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeJesus RS, Chaudhry R, Angstman KB, et al. Predictors of osteoporosis screening completion rates in a primary care practice. Popul Health Manag. 2011;14(5):243–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bili A, Schroeder LL, Ledwich LJ, Kirchner HL, Newman ED, Wasko MC. Patterns of preventive health services in rheumatoid arthritis patients compared to a primary care patient population. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31(9):1159–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ornstein S, Jenkins J. The Practice Partner Research Network: Description of a Novel National Research Network of Computer-based Patient Records Users. Carolina Health Services and Policy Review. 1997;4:145–151 [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/recommendations.htm Accessed Jun 6, 2012

- 9.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Health Care Program Priority Conditions for Comparative Effectiveness Research. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/index.cfm/submit-a-suggestion-for-research/how-are-research-topics-chosen/ Accessed Jun 13, 2012

- 10.Committee on Comparative Effectiveness Research Prioritization, Institute of Medicine Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=12648&page=R1 Accessed Jun 13, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCulloch CESS. Generalized, Linear, and Mixed Models. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stange KC, Flocke SA, Goodwin MA. Opportunistic preventive services delivery. Are time limitations and patient satisfaction barriers? J Fam Pract. 1998;46(5):419–424 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fortin M, Stewart M, Poitras ME, Almirall J, Maddocks H. A systematic review of prevalence studies on multimorbidity: toward a more uniform methodology. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(2):142–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrante JM, Balasubramanian BA, Hudson SV, Crabtree BF. Principles of the patient-centered medical home and preventive services delivery. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(2):108–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaén CR, Ferrer RL, Miller WL, et al. Patient outcomes at 26 months in the patient-centered medical home National Demonstration Project. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):S57–67; S92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nemeth LS, Ornstein SM, Jenkins RG, Wessell AM, Nietert PJ. Implementing and evaluating electronic standing orders in primary care practice: a PPRNet study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(5):594–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mold JW, Aspy CA, Nagykaldi ZOklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network Implementation of evidence-based preventive services delivery processes in primary care: an Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(4):334–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]