Abstract

A 44-year-old man is presented here with 14 years of chronic purulent sinusitis, a chronic fungal rash of the scrotum, and chronic pelvic pain. Treatment with antifungal therapy resulted in symptom improvement, however he was unable to establish an effective long-term treatment regimen, resulting in debilitating symptoms. He had undergone extensive work-up without identifying a clear underlying etiology, although Candida species were cultured from the prostatic fluid. 100 genes involved in the cellular immune response were sequenced and a missense mutation was identified in the Ras-binding domain of PI3Kγ. PI3Kγ is a crucial signaling element in leukotaxis and other leukocyte functions. We hypothesize that his mutation led to his chronic infections and pelvic pain.

Introduction and Materials and Methods

Case Report

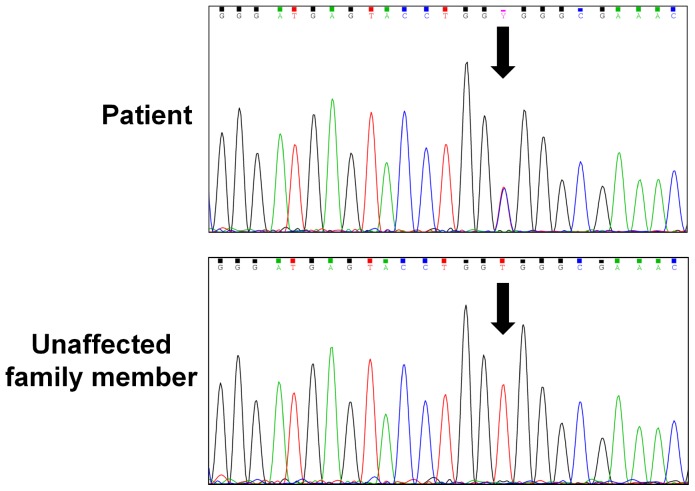

A 44 year-old male presented with 14 years of chronic infections and pelvic pain. Although subject to frequent respiratory and gastrointestinal infections since childhood, his pelvic pain began at age 30. Following initiation of antibiotic and corticosteroid treatment for acute sinusitis, he developed a painful erythematous scrotal rash. His core symptoms are presented in Table S1. He initially attempted treatment with antifungals with mild improvement, but his rash gradually worsened over time. After another course of antibiotics for acute sinusitis, his rash spread to the glans penis and he subsequently developed severe urethral, testicular, and pelvic pain. He also began having chronic purulent sinusitis, and since that time he has struggled to control his upper respiratory symptoms, pelvic pain, and scrotal rash. The dynamics of his symptoms over time is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Dynamics of Symptoms over Time.

Rash and sinusitis symptom severity presented on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being worst. NIH-CPSI scores presented on the respective scales: NIH-CPSI Pain Domain: 0–21, NIH-CPSI Voiding Domain: 0–10, NIH-CPSI Quality of Life Impact Domain: 0–12 and Total NIH-CPSI Score: 0–43 (from Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ Jr, Nickel JC, Calhoun EA, et. al. (1999) The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Urol 162∶369-75.

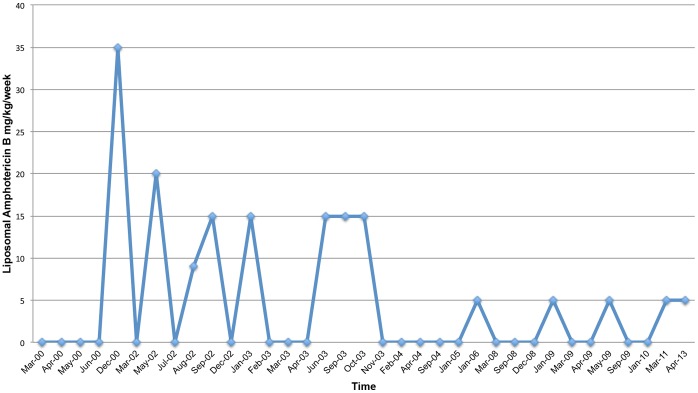

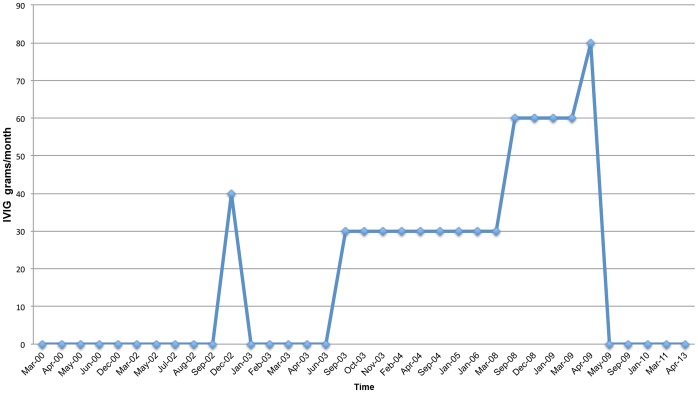

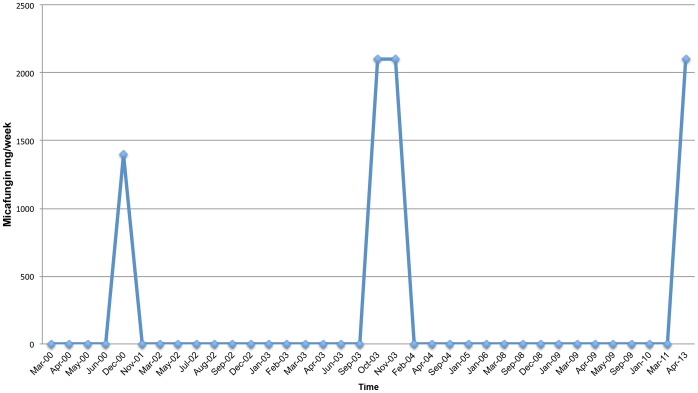

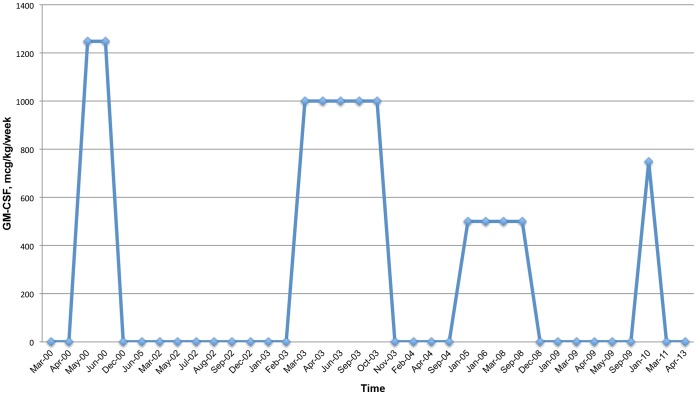

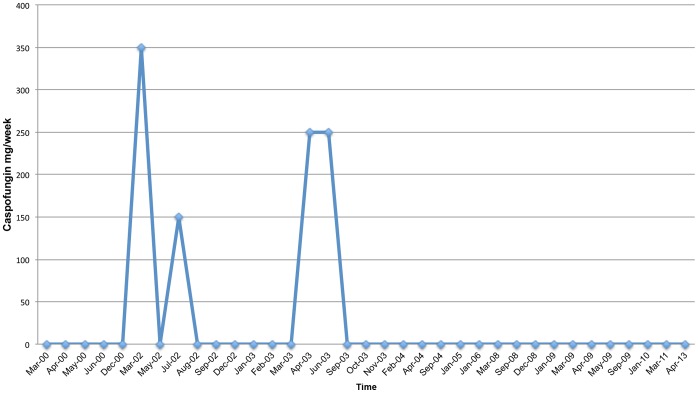

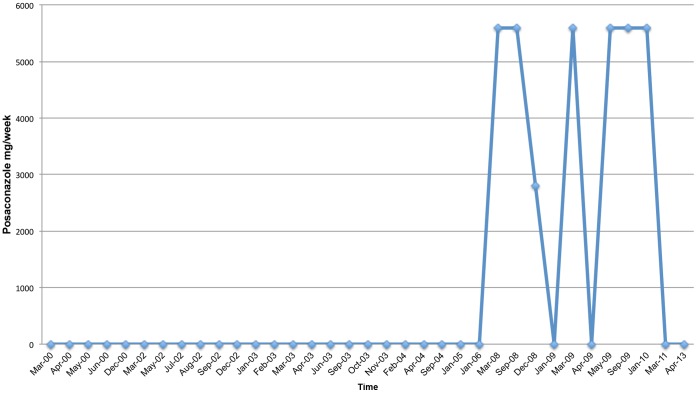

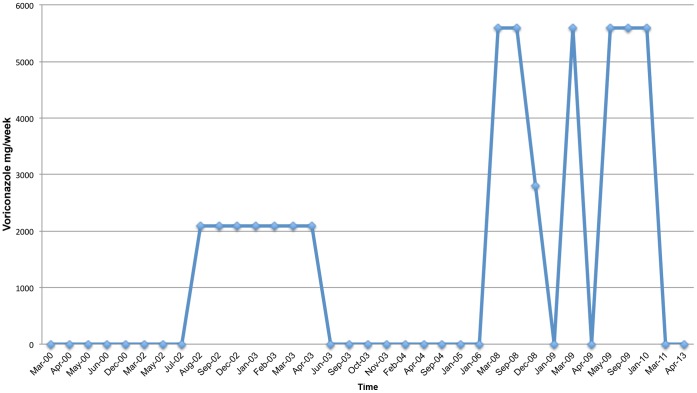

He has undergone treatment with numerous immunologic and antifungal therapies including G-CSF, IFN-gamma, GM-CSF, IVIG, IL-2, fluconazole, amphotericin B, micafungin, itraconazole, caspofungin, voriconazole, with varying levels of success (Figures 2–8). He experienced substantial improvement of his pelvic pain and skin lesions and mild improvement of his upper respiratory symptoms with micafungin but had to forego therapy for financial reasons (Figure 1 and Figure 5). Other regimens including GM-CSF (Figure 3) with fluconazole and amphotericin (Figure 2) with caspofungin (Figure 4) have also helped control symptoms, but to a lesser degree. He has consistently noted worsening of his pelvic pain, rash, and upper respiratory symptoms with antibiotic treatments. Unfortunately, medication costs and side effects have prohibited the establishment of a successful long-term regimen. His pelvic pain and the fatigue associated with his symptoms have significantly impacted his quality of life. His pelvic pain limits his ability to sit for long periods of time, and his sinusitis is associated with pharyngitis, headaches, fatigue, and malaise. These symptoms have limited his ability to work, exercise, maintain a social life, and enjoy dating or sexual activity.

Figure 2. Liposomal Amphotericin B (AmBisome) Treatment Schedule.

Figure 8. IVIG Treatment Schedule.

Figure 5. Micafungin Treatment Schedule.

Figure 3. GM-CSF Treatment Schedule.

Figure 4. Caspofungin Treatment Schedule.

Figure 6. Posaconazole Treatment Schedule.

Figure 7. Voriconazole Treatment Schedule.

He has undergone extensive work-up, which has failed to identify a unifying underlying diagnosis (Tables 1, 2, and 3 and Tables S2, S3, S4). Prostatic fluid and ejaculate cultures, however, have grown multiple Candida species (Table 4), and immunologic testing has demonstrated anergy to Candida antigen (Table S3).

Table 1. WBC, Flow Cytometry (CD4/CD8) Cell, and NK Cell Profile.

| Test | March 1999 | May 2000 | September 2000 | Units | Reference Range |

| WBC | 6.9 | 27.7 | 5.7 | K/cumm | 4.5–11 |

| RBC | 4.75 | 4.63 | 5.05 | M/cumm | 4.30–5.90 |

| HGB | 15.3 | 14.4 | 15.9 | g/dL | 13.9–18.0 |

| HCT | 46.2 | 41.3 | 44 | % | 39–55 |

| PLT | 179 | 189 | 178 | K/cumm | 130–400 |

| NEU | 66.1 | 89 | 60 | % | 45.7–75.1 |

| LYM | 18.6 | 7 | 25.3 | % | 14.6–41 |

| MONO | 10.8 | 4 | 6.2 | % | 4–12.4 |

| EOS | 4.1 | 1 | 8 | % | 0–5.6 |

| BASO | 0.4 | 0 | 0.5 | % | 0–1.2 |

| NEU | 4.6 | 24.6 | 3.4 | # | 1.5–8.5 |

| LYM | 1.3 | 1.8 | # | 1–4.8 | |

| MONO | 0.7 | 1.1 | # | 0.2–0.8 | |

| EOS | 0.3 | 0.2 | # | 0–0.7 | |

| BASO | 0 | 0 | # | 0–0.2 | |

| Flow Cytometry | |||||

| TOTAL WBC | 6900 | 27700 | 5700 | /cumm | 3800–10800 |

| LYMPH % | 93 | 3 | 25.3 | % | 10–40 |

| LYMPH ABS # | 850 | 831 | 1442 | /cumm | 1200–3700 |

| CD3% | 77 | 71 | 74.2 | % | 60–84 |

| CD3 ABS # | 658 | 590 | 1070 | /cumm | 670–2450 |

| CD4% | 52 | 43 | 43.2 | % | 32–57 |

| CD4 ABS # | 439 | 357 | 623 | /cumm | 400–1500 |

| CD8% | 23 | 23 | 25.9 | % | 14–35 |

| CD8 ABS # | 192 | 191 | 373 | /cumm | 140–950 |

| CD4:CD8 RATIO | 2.26 | 1.87 | 1.668 | ratio | 0.80–3.20 |

| Natural killer function | 5 | N/A | N/A | LU | 20–250 |

| CD 16/56% | N/A | N/A | 11.1 | % | 3.2–23.7 |

| CD 16/56 ABS | N/A | N/A | 160 | CELLS/UL | 45–523 |

Table 2. STD and Hepatitis Panel Results.

| Test | Sample | 1999 | 2008 | Reference |

| RPR | Serum | Nonreactive | N/A | Nonreactive |

| HBsAg | Serum | Negative | N/A | Negative |

| HBsAb | Serum | Negative | N/A | Negative |

| HBcAb | Serum | Negative | N/A | Negative |

| HCV AB | Serum | Negative | N/A | Negative |

| HIV I & II antibodies | Serum | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | Urine | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Urine | Negative | Negative | Negative |

Table 3. Imaging Test and Special Test/Procedure Results.

| Test/Procedure | Date | Result |

| Imaging Tests | ||

| CT chest | 2008 | Minimal lung scarring, previous spinal surgery |

| CT pelvis | 2008 | Prostate not enlarged (3.8×2.6 cm), no calcifications |

| Surgeries | ||

| Cystoscopy | Declined | N/A |

| Bilateral endoscopic and laser frontomaxiloethmoidsphenoidectomies, septoplasty and submucous resection of turbinates | 1998 | Diagnosis: Severe obstructive rhinosinusitis with deviated nasal septum and hypertrophic turbinates |

| Procedures | ||

| Cystoscopy | Declined | N/A |

Table 4. Fungal Culture and Sensitivity Testing Results (Prostatic Fluid and Ejaculate).

| Isolate | Candida albicans | Candida glabrata | Periconia species | |||

| Source | Prostatic secretions | Ejaculate | Ejaculate | |||

| Date | January 2000 | March 2002 | August 2003 | |||

| MIC, mcg/mL @ | 24 hrs | 48 hrs | 24 hrs | 48 hrs | 24 hrs | 48 hrs |

| Amphotericin B | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 5-FC | N/A | N/A | 2 | 4 | N/A | N/A |

| Ketoconazole | N/A | N/A | 0.125 | 0.125 | N/A | N/A |

| Fluconazole | 0.25 | 0.25 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 32 |

| Itraconazole | < = 0.015 | < = 0.015 | 0.125 | 0.125 | N/A | N/A |

| Voriconazole | N/A | N/A | < = 0.125 | < = 0.125 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Posaconazole | < = 0.015 | < = 0.015 | 0.06 | 0.06 | N/A | N/A |

| Caspofungin | N/A | N/A | < = 0.125 | < = 0.125 | 8 | 8 |

We hypothesized that defects in the cellular immune response may underlie his clinical condition, as we have demonstrated previously in other chronic fungal infections. [1], [2] The current study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Children’s Hospital Boston, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. The individual in this manuscript has given written informed consent to publish these case details, as outlined in the PLoS consent form available at: http://www.plosone.org/static/plos_consent_form.pdf.”

Results

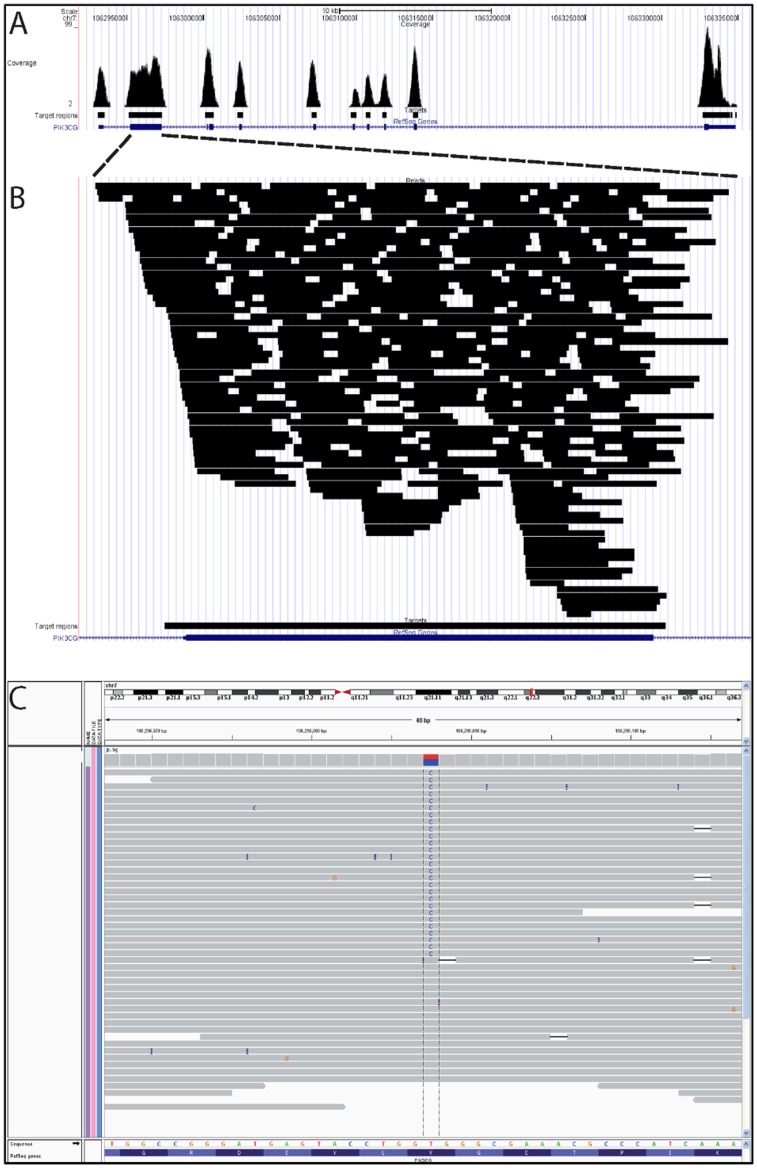

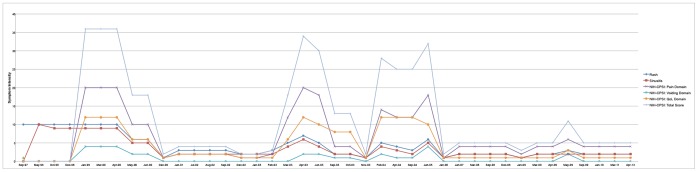

A panel of 100 genes known to induce or modulate the immune response was sequenced, [1] revealing a heterozygous mutation in the gene PIK3CG, corresponding to a Val282Ala amino acid substitution in the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase gamma (PI3Kγ) protein (Tables 5 and 6, Figures 9 and 10). The brother and the father of the patient tested negative for this mutation in PIK3CG, suggestive of a de novo mutation. Unfortunately, this could not be definitively confirmed by the DNA analysis of the patient’s mother, as she was deceased (Table 7). The mutation is not a known polymorphism, based on its absence in 100 in-house exome datasets from individuals of European ancestry, and from 179 individuals sequenced as part of the 1000 genomes project. [3] Based on a Grantham score of 64, this mutation is predicted to be poorly tolerated for maintaining protein conformation.

Table 5. Coverage Statistics of the Exome Sequencing Procedure of the Patient.

| SMB | |

| Total mapped | 21112862 |

| On target* | 72.34% |

| Near target** | 25.26% |

| Off target*** | 2.40% |

| Average target coverage | 30.03 |

On target: mapping to bases included in the array design

Near target: In 500 basepair (approximate fragment length) proximity of array targets

Off target: Mapping to other genomic positions in the genome

Table 6. Summary of All Genetic Variants Detected in the Patient.

| CMC-SMB | |

| Total variants | 895 |

| of those SNVs | 794 |

| of those indels | 101 |

| Known SNPs (dbSNP 130) | 827 |

| In-house variants | 91 |

| Novel variants | 57 |

| of those coding (non-synonymous) | 7 |

| of those minimal 20% variant reads | 1 |

Figure 9. Coverage of the PI3KCG Gene Specifically.

Figure 10. Validation of Mutation by Sanger Sequencing.

Table 7. Family History.

| Relative | Status/Description |

| Mother | Deceased: Colon cancer. Chronic respiratory symptoms in response to mold in the office building where she worked. She subsequently became very sensitive to air pollution, tobacco smoke, and molds. Migraine headaches that kept her in bed for days. Alcohol caused severe headaches, which would lead to vomiting. Two miscarriages, two other pregnancies (patient and his brother) uneventful |

| Father | Alive, well, 75-years old. Hypertension. Cataract surgery, otherwise in good health |

| Brother | 37- years old. History of frequent ear infections as a child. Current symptoms: severe acne, hives, and rosacea. Ongoing difficulties with coordination, experiences tics in his eyebrows. Ongoing sleep difficulties, but MRI and psychiatric examination were not indicative of any pathological conditions. Has difficulty keeping a job, lives with father |

| Maternal grandfather | Deceased of stomach cancer at age 77, otherwise healthy prior to cancer onset |

| Maternal grandmother | Deceased at age 90 |

| Paternal grandmother | Deceased of breast cancer in her 70 s |

| Paternal grandfather | Deceased of a heart attack in his late 60 s |

Discussion

We present a patient with chronic infections and pelvic pain, found to have a novel missense mutation in PI3Kγ: a signaling molecule involved in a wide variety of cellular functions, including leukotaxis. There are currently no descriptions of PIK3GC germline mutations in humans with associated clinical phenotypes. We hypothesize that the patient’s mutation is responsible both for his predisposition to chronic infections and his chronic pelvic pain.

Chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) is defined as greater than three months of pelvic pain over a six month period with no established etiology based on routine testing. [4] Pain symptoms can occur in the perineum, lower abdomen, testicles, penis, and with ejaculation, and patients can also experience voiding dysfunction. CPPS has been estimated to account for nearly two million annual physician visits, [5] and its impact on quality of life is similar to or greater than angina, congestive heart failure, Crohn’s disease, and diabetes mellitus. [6] While the etiology and pathophysiology are not well understood, many experts favor a model of CPPS as a heterogeneous condition, with multiple potentially overlapping etiologies existing along a spectrum. This patient’s history may suggest a chronic fungal infection, or potentially an autoimmune process precipitated by an inciting fungal infection, as the cause of his CPPS. While infectious and autoimmune mechanisms have been proposed in CPPS, they have never been proven responsible in specific cases. Furthermore, while multiple levels of evidence support a genetic underpinning in CPPS, a specific mutation has never been proven responsible. Recent evidence from the Northwestern University Prostatitis Research group implicates mast cells in the pathogenesis of CPPS. [7], [8] Activation may result in the release of vasoactive and inflammatory molecules in response to unknown triggers. [9] This activation is known to be significantly dependent on PI3K-γ. [10].

Despite a wide range of roles in cells throughout the body, PI3Kγ has largely been studied for its importance within the immune system, where it participates in leukotaxis and other elements of the immune response. Class I PI3Ks are heterodimers consisting of a catalytic and a regulatory subunit that is further grouped into Class IA and IB, each with respective isoforms. Class IA PI3Ks are activated by receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), whereas class IB is activated through G protein coupled receptors (GPCR). [11], [12] PI3Kγ consists of a catalytic subunit, p110γ, and regulatory subunits, p101 or p84/p87. [13] Upon binding of chemokines or other ligands to GPCRs, PI3Kγ is activated through binding to the βγ subunit of a heterotrimeric G-protein. PI3Kγ activation is also enhanced by binding of the GTPase Ras to the Ras-binding domain of p110γ, which lies directly adjacent to the catalytic domain. [13] This initiates the signaling cascade that results in chemotaxis in multiple leukocyte lineages, both within the adaptive and innate immune responses. In addition, it activates other leukocyte functions, including the oxidative burst in neutrophils. [14] In vivo models have demonstrated decreased inflammation and susceptibility to infections when PI3Kγ function is abrogated, making it an attractive target in the treatment of inflammatory, allergic and autoimmune diseases. [14], [15].

Beer-Hammer and colleagues demonstrated that p110γ contributes to T and B cell development, and is variably expressed throughout the hematopoietic process. [16] The γ catalytic subunit plays a very different role from other IB class members, directly interacting with the G-protein βγ dimers and Ras proteins. Several studies have looked at p110γ/p110δ mutants p110γ-deficient animals, homozygous for a KD p110δ mutant, show profound T cell lymphopenia accompanied by multiple organ inflammation,[15], [17]–[19] while mutations only in p110γ primarily causes defects in neutrophil and mast cell function. [19] These mutations have shown specificity in affecting TCR-induced T cell activation. [18] PI3Kγ has been implicated in leukocyte migration, regulation of T-cell proliferation and cytokine release, 10 and most recently mast cell activation. 20 Overexpression of p110γ was shown to induce oncogenic transformation of chicken embryo fibroblasts, if Ras binding occurred. 21 P110γ overexpression has also been documented in chronic myeloid leukemia, 22 presenting it as an potential oncogene through the recent literature.

The Val282Ala mutation occurs within the Ras-binding domain of the p110γ subunit of PI3Kγ. Functional studies will be necessary to determine the specific effect of the Val282Ala mutation on the activity of PI3Kγ, but one can hypothesize that decreased activity could suppress the immune response by inhibiting leukocyte migration and function. This could explain the patient’s history of frequent and chronic infections. Additionally, it could potentially explain his chronic pelvic pain, through several different mechanisms. The history suggests that the patient’s cutaneous fungal infection likely spread to the urinary tract after extending to the glans penis, and may have subsequently involved the urethra, epididymis, testicles, prostate, or other areas within the genitourinary system. With failure to completely eradicate the infection due to impaired leukocyte activity, chronic infection alone may have caused his pain symptoms. Another possibility is that the initial infection within the genitourinary system may have been effectively treated by antifungal therapy but subsequently incited an autoimmune process, which can result from infection via multiple mechanisms. [23] Alternatively, a mutation in PI3KCG that resulted in over-activation could cause inflammation through an autoimmune mechanism, resulting in chronic pelvic pain. Further studies will be necessary to determine the activity of the mutant protein and elucidate the exact mechanisms of injury.

Supporting Information

Core Symptoms.

(DOCX)

Immunoglobulin and IgG Subclass Profile.

(DOCX)

Lymphocyte Antigen and Mitogen Proliferation Assays.

(DOCX)

Toll-Like Receptor Function Assays.

(DOCX)

Funding Statement

This work was supported by a Vici Grant of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. van de Veerdonk FL, Plantinga TS, Hoischen A, Smeekens SP, Joosten LA, et al. (2011) STAT1 mutations in autosomal dominant chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. N Engl J Med 365: 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chai LY, Naesens R, Khoo AL, Abeele MV, van Renterghem K, et al. (2011) Invasive fungal infection in an elderly patient with defective inflammatory macrophage function. Clin Microbiol Infect 17: 1546–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, et al. (2010) A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 467: 1061–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krieger JN, Nyberg L, Nickel JC (1999) NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. JAMA 282: 236–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Collins MM, Stafford RS, O’Leary MP, Barry MJ (1998) How common is prostatitis? A national survey of physician visits. J Urol 159: 1224–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McNaughton Collins M, Pontari MA, O’Leary MP, Calhoun EA, Santanna J, et al. (2001) Quality of life is impaired in men with chronic prostatitis: the Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Gen Intern Med 16: 656–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Done JD, Rudick CN, Quick ML, Schaeffer AJ, Thumbikat P (2012) Role of mast cells in male chronic pelvic pain. J Urol 187: 1473–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Quick ML, Mukherjee S, Rudick CN, Done JD, Schaeffer AJ, et al. (2012) CCL2 and CCL3 are essential mediators of pelvic pain in experimental autoimmune prostatitis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 303: R580–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desireddi N, Campbell P, Stern J, Sobkoviak R, Chuai S, et al.. (2008) Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha as possible biomarkers for the chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol 179: 1857–1861; discussion 1861–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10. Hirsch E, Katanaev VL, Garlanda C, Azzolino O, Pirola L, et al. (2000) Central role for G protein-coupled phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma in inflammation. Science 287: 1049–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stephens L, Smrcka A, Cooke FT, Jackson TR, Sternweis PC, et al. (1994) A novel phosphoinositide 3 kinase activity in myeloid-derived cells is activated by G protein beta gamma subunits. Cell 77: 83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stephens LR, Eguinoa A, Erdjument-Bromage H, Lui M, Cooke F, et al. (1997) The G beta gamma sensitivity of a PI3K is dependent upon a tightly associated adaptor, p101. Cell 89: 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pacold ME, Suire S, Perisic O, Lara-Gonzalez S, Davis CT, et al. (2000) Crystal structure and functional analysis of Ras binding to its effector phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma. Cell 103: 931–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barberis L, Hirsch E (2008) Targeting phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma to fight inflammation and more. Thromb Haemost 99: 279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Camps M, Rückle T, Ji H, Ardissone V, Rintelen F, et al. (2005) Blockade of PI3Kgamma suppresses joint inflammation and damage in mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Med 11: 936–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beer-Hammer S, Zebedin E, von Holleben M, Alferink J, Reis B, et al. (2010) The catalytic PI3K isoforms p110gamma and p110delta contribute to B cell development and maintenance, transformation, and proliferation. J Leukoc Biol 87: 1083–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ji H, Rintelen F, Waltzinger C, Bertschy Meier D, Bilancio A, et al. (2007) Inactivation of PI3Kgamma and PI3Kdelta distorts T-cell development and causes multiple organ inflammation. Blood 110: 2940–2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alcázar I, Marqués M, Kumar A, Hirsch E, Wymann M, et al. (2007) Phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma participates in T cell receptor-induced T cell activation. J Exp Med 204: 2977–2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Garçon F, Patton DT, Emery JL, Hirsch E, Rottapel R, et al. (2008) CD28 provides T-cell costimulation and enhances PI3K activity at the immune synapse independently of its capacity to interact with the p85/p110 heterodimer. Blood 111: 1464–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laffargue M, Calvez R, Finan P, Trifilieff A, Barbier M, et al. (2002) Phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma is an essential amplifier of mast cell function. Immunity 16: 441–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kang S, Denley A, Vanhaesebroeck B, Vogt PK (2006) Oncogenic transformation induced by the p110beta, -gamma, and -delta isoforms of class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 1289–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hickey FB, Cotter TG (2006) BCR-ABL regulates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-p110gamma transcription and activation and is required for proliferation and drug resistance. J Biol Chem 281: 2441–2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ercolini AM, Miller SD (2009) The role of infections in autoimmune disease. Clin Exp Immunol 155: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Core Symptoms.

(DOCX)

Immunoglobulin and IgG Subclass Profile.

(DOCX)

Lymphocyte Antigen and Mitogen Proliferation Assays.

(DOCX)

Toll-Like Receptor Function Assays.

(DOCX)