Abstract

Background

Femoral neck fractures (FNFs) comprise 50% of geriatric hip fractures. Appropriate management requires surgeons to balance potential risks and associated healthcare costs with surgical treatment. Treatment complications can lead to reoperation resulting in increased patient risks and costs. Understanding etiologies of treatment failure and the population at risk may decrease reoperation rates.

Questions/purposes

We therefore (1) determined if treatment modality and/or displacement affected reoperation rates after FNF; and (2) identified factors associated with increased reoperation and timing and reasons for reoperation.

Methods

We reviewed 1411 records of patients older than 60 years treated for FNF with internal fixation or hemiarthroplasty between 1998 and 2009. We extracted patient age, sex, fracture classification, treatment modality and date, occurrence of and reasons for reoperation, comorbid conditions at the time of each surgery, and dates of death or last contact. Minimum followup was 12 months (median, 45 months; range, 12–157 months).

Results

Internal fixation (hazard ratio [HR], 6.38) and displacement (HR, 2.92) were independently associated with increased reoperation rates. The reoperation rate for nondisplaced fractures treated with fixation was 15% and for displaced fractures 38% after fixation and 7% after hemiarthroplasty. Most fractures treated with fixation underwent reoperation within 1 year primarily for nonunion. Most fractures treated with hemiarthroplasty underwent reoperation within 3 months, primarily for infection.

Conclusions

Overall, hemiarthroplasty resulted in fewer reoperations versus internal fixation and displaced fractures underwent reoperation more than nondisplaced. Our data suggest there are fewer reoperations when treating elderly patients with displaced FNFs with hemiarthroplasty than with internal fixation.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Femoral neck fractures (FNFs) are common, accounting for approximately 50% of all hip fractures [30]. The number of people in the United States older than 65 years in 2010 was 40 million and will nearly double to 80 million by 2040 [21]. With this elderly population increase, the rate of hip fractures is expected to increase from less than 2 million in 1990 to more than 6 million by 2050 [28]. The increasing yearly prevalence and morbidity and mortality associated with FNFs have led to extensive research and multiple publications on which to base treatment decisions [1, 4, 5, 9, 19, 25, 26, 31, 33, 36, 38, 42, 45, 47–49, 51].

Patient factors relevant to the treatment of this injury include age, activity, comorbidities, functional demands, and the perceived risk of secondary surgery [3, 9, 21–23, 33, 44, 45, 51]. These must be considered alongside surgeon preference and fracture variables that include displacement, fracture pattern, comminution, and bone quality [7, 11, 21, 25, 45, 51]. Treatment options include nonsurgical management [13, 35, 36], internal fixation with multiple cannulated screws [11, 22, 24, 31, 40, 47, 51, 52], hemiarthroplasty [3, 8, 18, 24, 54], or THA [3, 5, 10, 12, 42, 50].

As a result of the widely published differences in the reoperation rates after initial surgical treatment of nondisplaced [7, 11–13, 21, 45, 47] versus displaced FNFs [3, 8, 18, 22, 31, 38, 42, 44, 52], research has been directed at looking separately at nondisplaced or displaced fractures. Evidence of better hip function scores, quality of life, and lower reoperation rates of THA compared with internal fixation strongly supports the use of THA in healthy, cognitively intact patients [3, 8, 10, 28, 42, 43, 50, 51]. The use of internal fixation in FNFs has been associated with reoperation rates ranging from 10% to 49% [18, 21, 22, 24, 42, 44] compared with 0% to 24% for hemiarthroplasty [5, 18, 36, 44], resulting in a more costly treatment strategy than hemiarthroplasty [1, 25]. Despite increased complications and technical difficulties associated with salvage of failed fixation [16, 23, 34], some argue the higher reoperation rate is offset by the benefits of preservation of the native femoral head and avoidance of potential complications associated with arthroplasty [2, 13, 31]. Mortality at 1 year ranges from 14% to 36% but without differences in mortality between fixation and hemiarthroplasty at 1, 5, and 10 years [8, 18, 19, 31, 36, 37]. Fixation is associated with higher risk of contralateral hip fracture than arthroplasty [48]. Despite the growing amount of research on this subject, no clinical consensus exists regarding how to best treat FNFs with the primary intention of avoiding reoperation in an effort to avoid additional risks to these patients.

Therefore, our purpose was to (1) determine if treatment modality and/or displacement affected reoperation rates after FNF; and (2) identify factors associated with increased reoperation and the timing and reasons for reoperation.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed our institutional electronic medical record from 1998 to 2009 using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision and Current Procedural Terminology codes associated with FNFs (27235, 27236, 27132, and 27130) and identified 1788 patients. For this study we included patients meeting the following criteria: age older than 60 years and treatment for FNF. We excluded 377 patients sustaining trauma beyond a simple fall, those with concurrent malignancies, extracapsular hip fracture (OTA/AO 31-B2.1 [31]), prior surgery to the ipsilateral proximal femoral region, and those receiving open reduction or treatment other than internal fixation or hemiarthroplasty. Among the 1788 charts reviewed, 1411 patients (1494 hips) with FNF treated with fixation or hemiarthroplasty met inclusion criteria. Thirteen cases of nondisplaced fractures treated with hemiarthroplasty were excluded, because the standard of care at this institution during this time was to perform internal fixation on nondisplaced fractures unless extenuating circumstances led the surgeon to choose differently. We assumed that the factor(s) that led to the decision in these patients would qualify these cases as outliers. There were 117 patients excluded owing to lack of 1 year of followup. Reoperation-free survival analysis was performed on 1294 patients (1364 hips) who died without reoperation, were followed at least 1 year without reoperation, or underwent reoperation. There were 620 patients treated for a left hip fracture, 604 patients treated for a right hip fracture, and 70 patients treated for bilateral hip fractures. One thousand thirteen fractures (74%) were in females and 351 (26%) were in males. The average age at index surgery was 81 years (SD, 8; range, 60–106 years). Minimum followup of the 1364 fractures was 0 month (median, 23 months; range, 0–157 months), which included 847 (65%) cases in which the patient died, one of whom died the date of surgery yielding the minimum range of 0. Among 1364 total cases, there were 227 reoperations during followup. The remaining patients with 1137 fractures were censored at the last contact date or date of death with a minimum followup of 12 months (median, 45 months; range, 12–157 months) for patients who survived without reoperation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Revision-free survival estimate (number of patients remaining)

| Garden stage | Surgery type | Median revision-free survival | Estimated percent revision-free survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month | 3 months | 12 months | 36 months | |||

| Nondisplaced | IF (N = 358) | NR* | 98.0% (N = 336) | 95.3% (N = 311) | 86.8% (N = 251) | 82.1% (N = 136) |

| Displaced | HA (N = 667) | NR* | 96.5% (N = 591) | 94.7% (N = 545) | 94.2% (N = 474) | 93.1% (N = 270) |

| IF (N = 339) | NR* | 95.5% (N = 303) | 86.3% (N = 259) | 65.7% (N = 177) | 56.4% (N = 102) | |

* NR = median revision-free survival was not reached; IF = internal fixation; HA = hemiarthroplasty.

The indications for fixation were (1) nondisplaced fractures; (2) stable fractures; or (3) minimally displaced fractures amenable to closed reduction with intact posteromedial cortex. The indications for hemiarthroplasty were (1) minimally displaced fractures with disrupted posteromedial cortex; or (2) displaced fractures. The contraindications for surgery were (1) nonambulatory patients with severe dementia; or (2) patients deemed too unhealthy for surgery. Six hundred ninety-seven (51%) of the fractures were treated with fixation and 667 (49%) were treated with hemiarthroplasty. Three hundred fifty-eight (26%) of the fractures were nondisplaced and all were treated with fixation. A total of 1006 fractures (74%) were displaced, of which 667 were treated with hemiarthroplasty and 339 were treated with fixation. For both surgical treatments, surgery was performed or overseen by one of 20 senior staff physicians. Patients treated with multiple screws underwent reduction through closed means on a fracture table and implant placement as described by Probe and Ward [41]. Three ASNIS III (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) 6.5-mm cannulated screws were used for fixation on all patients with a fourth screw added if posterior comminution was present [30]. All hemiarthroplasties were performed using a Hardinge lateral approach combined with a modular stem using third-generation cementing techniques.

Postoperatively, patients were allowed to weightbear with unrestricted hip motion as tolerated and were evaluated and managed by a physical therapist. Patients were discharged to nursing homes, skilled nursing facilities, or rehabilitation centers with continuation of physical therapy or were discharged to home with home physical therapy if deemed capable. All patients had their incision evaluated at 2 weeks. Reductions were assessed intraoperatively by fluoroscopy and with routine radiographs at 6 weeks for all patients and were taken accordingly when pain, reinjury, or patient complaint caused concern.

Data obtained from chart review included patient age, sex, surgery performed, date of surgery, fracture classification, complications leading to reoperation, and dates of last contact or death. Patients’ death records were obtained from our state’s vital statistics based on name, date of birth, and sex. Reoperation was defined as any operation performed owing to complications of the primary procedure. Reason for reoperation was identified retrospectively from review of orthopaedic and radiologic records and classified based on a Cochrane review classification [37] as (1) minor (removal of fixation, closed reduction of dislocated prosthesis); (2) moderate (arthroplasty after fixation, surgical drainage, open reduction of dislocated prosthesis, resection arthroplasty or similar removal of implant and femoral head); or (3) major (conversion of hemiarthroplasty to THA or other revision arthroplasty, periprosthetic fracture). There were six reasons for reoperation in the fixation group according to the primary etiology, which included nonunion, avascular necrosis, prominent hardware from collapse causing pain or screw protrusion through the femoral head, deep infection, periprosthetic fracture, and early loss of reduction. There were seven reasons for reoperation in the hemiarthroplasty group, including deep infection, periprosthetic fracture, heterotopic ossification, dislocation, femoral component loosening, hematoma, and superficial infection.

Fracture displacement was categorized as either nondisplaced or displaced by one of two methods. For patients sustaining their fracture after August 2002, digital radiographs were available for review by one of the authors (TR). Fractures were categorized as nondisplaced if they were AO/OTA 31B3.1-3 (Garden Stages 1 and 2 [20]) and categorized as displaced if they were 31B3.1-3 or 31B2.3 (Garden Stages 3 and 4). The intergrader agreement for Garden Stages 1, 2, 3, and 4 fractures is reportedly low (kappa, 0.03–0.56) but high (kappa, 0.67–0.77) for nondisplaced (Garden Stages 1 and 2) and displaced (Garden Stages 3 and 4) fractures [17, 36, 55]. A subset of radiographs was used to assess and ensure interobserver reliability with two board-certified trauma surgeons and four chief residents. Consistent with previous reports, intergrader reliability was greater than 90% for nondisplaced and displaced fracture groups [17, 35, 55]. For patients sustaining a fracture before August 2002, radiographic images were not available and displacement classification was discerned through review of orthopaedic and radiographic records. We considered this acceptable, because dichotomous classification (displaced/nondisplaced) reportedly has high intergrader reliability [17, 36, 55]. Early loss of reduction was defined as displacement from the surgical reduction within 3 months, determined by the treating surgeon to be unacceptable.

Case characteristics were summarized according to reoperation status (reoperation versus no reoperation) using descriptive statistics, mean (SD), or median (minimum-maximum) for continuous variables and frequency (percent) for categorical variables. Reasons of reoperation were summarized according to displacement and surgery type as frequency (percent). Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis (p < 0.05) was performed using age, sex, surgery type, and displacement status. A univariate Cox proportional hazards regression model (p < 0.05) using surgery type was applied to the displaced FNFs. Age, sex, time to reoperation, and reasons for reoperation were evaluated secondarily for their influence on reoperation rates. Implant survival was calculated for each case using Kaplan-Meier analysis. Patients who did not undergo reoperation were censored at last contact date or date of death. SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA) was used for data analysis.

Results

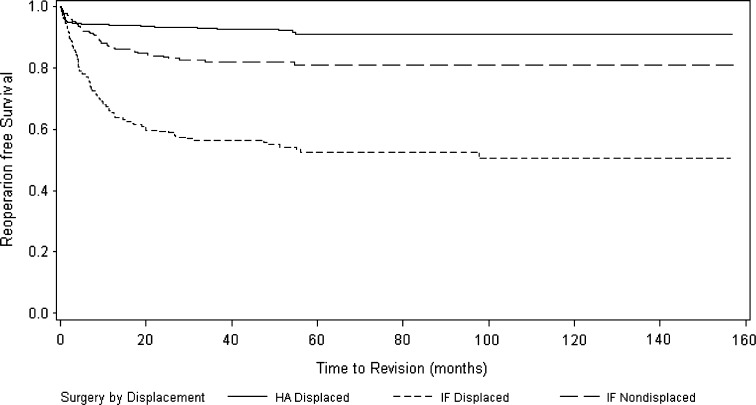

Treatment and displacement affected the rate of reoperation in patients with FNFs. Treatment with internal fixation (hazard ratio [HR], 6.38; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.51–9.05) and the presence of a displaced fracture (HR, 2.92; 95% CI, 2.12–4.02) were independently associated with increased risk of reoperation (Table 2). A total of 233 patients (227 fractures) required reoperation for an overall rate of 16.6%. For hemiarthroplasty and internal fixation overall, the reoperation rates were 6.6% and 26.3%, respectively. When comparing reoperation rates between surgery types in the displaced fractures only, fractures treated with internal fixation were greater than six times more likely to undergo reoperation (HR, 6.56; 95% CI, 4.65–9.24), with a reoperation rate of 6.6% for hemiarthroplasty and 38% for internal fixation (Table 3). The reoperation rate for nondisplaced fractures (all internal fixation) was 15.1%. Reoperation-free survival estimate at 1 year for the nondisplaced fixation group was 86.8% (95% CI, 82.5%–90.1%). The displaced group estimates were 94.1% for hemiarthroplasty and 65.7% for fixation (Fig. 1) (Table 1).

Table 2.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression for revision-free survival

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.17 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.00 | |

| Female | 0.99 (0.74–1.32) | 0.93 |

| Surgery type | ||

| Hemiarthroplasty | 1.00 | |

| Internal fixation | 6.38 (4.51–9.05) | < 0.001 |

| Displacement | ||

| Nondisplaced | 1.00 | |

| Displaced | 2.92 (2.12–4.02) | < 0.001 |

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Table 3.

Surgery type according to reoperation by displacement

| Variable | No reoperation | Reoperation | HR (95% CI) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nondisplaced only | ||||

| Internal fixation | 304 (84.9%) | 54 (15.1%) | ||

| Displaced only | ||||

| Hemiarthroplasty | 623 (92.4%) | 44 (6.6%) | 1.00 | |

| Internal fixation | 210 (62%) | 129 (38.1%) | 6.56 (4.65–9.24) | < 0.001 |

* Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression model was used; HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Fig. 1.

The Kaplan-Meier reoperation-free survival estimates are shown according to treatment and displacement. Hemiarthroplasty resulted in fewer reoperations versus internal fixation and displaced fractures underwent reoperation more than nondisplaced. The lines indicate the amount of time from surgery to revision for hemiarthroplasty (HA) displaced, internal fixation (IF) displaced, and IF nondisplaced fractures, respectively. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals at last followup: HA displaced (0.88–0.94), IF displaced (0.43–0.58), and IF nondisplaced (0.76–0.85).

Age and sex were not significant variables in the rate of reoperation (Table 2). For timing, most reoperations after fixation occur within 1 year and most reoperations after hemiarthroplasty occur within 3 months. In the patients treated with fixation, 42 (78%) with nondisplaced fractures who had reoperations and 101 (78%) with displaced fractures who had reoperations underwent reoperation within 1 year from surgery (Table 4). Thirty-three (75%) of the reoperations in patients treated with hemiarthroplasty occurred within 3 months. Nonunion was the most common reason for reoperation in the patients with nondisplaced fractures and displaced fractures treated with internal fixation. Infection was the leading reason for reoperation in patients with displaced fractures treated with hemiarthroplasty. Avascular necrosis, prominent screws, dislocation, and other reasons for reoperation were seen less commonly (Table 5).

Table 4.

Number of reoperations during each interval and number of cumulative reoperations

| Each interval | Nondisplaced | Displaced | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reoperation | IF (N = 358) | IF (N = 339) | HA (N = 667) |

| 0–1 month | 7 | 15 | 22 |

| 1–3 months | 9 | 28 | 11 |

| 3 months to 1 year | 26 | 58 | 3 |

| 1–3 years | 11 | 22 | 4 |

| More than 3 years | 1 | 6 | 4 |

| Cumulative | Nondisplaced | Displaced | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reoperation | IF (N = 358) | IF (N = 339) | HA (N = 667) |

| Within 1 month | 7 | 15 | 22 |

| Within 3 months | 16 | 43 | 33 |

| Within 1 year | 42 | 101 | 36 |

| Within 3 years | 53 | 123 | 40 |

IF = internal fixation; HA = hemiarthroplasty.

Table 5.

Reasons for reoperation

| Reoperation reason | Nondisplaced fracture | Displaced fracture Internal fixation | Hemiarthroplasty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal fixation (N = 358) | (N = 339) | (N = 667) | |

| Nonunion | 20 (5.6%) | 62 (18.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Avascular necrosis | 9 (2.5%) | 19 (5.6%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Prominent screws/screw protrusion | 12 (3.4%) | 18 (5.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 6 (1.7%) | 7 (2.1%) | 4 (0.6%) |

| Removal of heterotopic bone | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Dislocation | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (0.9%) |

| Femoral component loosening | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (0.7%) |

| Early loss of reduction | 7 (2.0%) | 18 (5.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Hematoma | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.3%) |

| Superficial infection | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.4%) |

| Deep infection | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (1.5%) | 23 (3.4%) |

| No reoperation | 304 (84.9%) | 210 (61.9%) | 623 (93.4%) |

| Reoperation classification Total (% of reoperations; % of total) |

|||

| Minor | 11 (20.4; 3.1) | 19 (14.7; 5.6) | 3 (6.8; 0.5) |

| Moderate | 37 (68.5; 10.3) | 103 (79.8; 30.3) | 28 (63.6; 4.2) |

| Major | 6 (11.1; 1.7) | 7 (5.4; 2.1) | 13 (29.5; 1.9) |

Discussion

The increasing yearly prevalence and morbidity and mortality associated with FNFs demands the medical community’s attention with the purpose of optimal management. Successful management requires the surgeon to balance potential risks and healthcare costs associated with surgery for FNF. One of these risks is reoperation. Higher reoperation rates have been associated with the use of fixation in FNFs [5, 18, 21, 22, 37, 39, 43, 45] resulting in a more costly treatment than hemiarthroplasty [1, 25]. Other associated risks of fixation include increased contralateral hip fractures [49] and complications and technical difficulties associated with salvage of failed fixation [16, 23, 34]. Despite the higher reoperation rates for internal fixation, advocates of this procedure argue this risk is offset by the benefits of preservation of the native femoral head and avoidance of potential complications of arthroplasty [2, 13, 31]. No clinical consensus exists regarding how to best treat FNFs with the primary intention of avoiding reoperation to avoid additional risks to patients. Therefore, our purpose was to (1) determine if treatment modality and/or displacement affected reoperation rates after FNF; and (2) identify factors associated with increased reoperation and the timing and reasons for reoperation.

We caution readers of the limitations of our study. First, postoperative radiographs were reviewed only for hip fractures on which reoperation was performed. This possibly could lead to underestimation of the occurrence rates of each mechanism of failure. For example, dislocation that undergoes closed reduction in the emergency room and does not proceed to surgery would not be included as a failure in this study. Despite this, our primary outcome measure was reoperation and therefore by design did not include failures not leading to reoperation. Second, during this study period, the treatment modality for displaced FNFs was determined by each staff physician but in keeping with the literature and standard of care at this institution. A shift of treatment modality occurred in 2001, and by 2006, internal fixation of displaced fractures rarely was performed at our institution unless patient factors prevented them from being able to undergo arthroplasty. Leading up to this shift, multiple publications were released noting the efficacy of internal fixation of displaced femoral neck fractures [14, 16, 25, 27, 41–43, 50, 52]. Overall, the inability to control for the exact treatment modality applied in each case is cause for caution in generalizing our results. Third, small variations in surgical technique by the surgeons involved were likely with the many patients treated. Because there was no way to control for these variations retrospectively, they may have had a negative or positive effect, which is not readily evident. However, because surgeon variability was inevitable, but approach and implant remained constant, our findings related to treatment can be attributed more confidently to the surgery rather than the surgeon. Fourth, complications were classified according to minor, moderate, and major based on type of reoperation. This classification scheme did not account for nonsurgical complications and subsequent reoperations because they were not recorded in our chart review. This possibly could contribute to underestimation of the overall morbidity of the procedure and therefore the severity classification. Whether a patient underwent reoperation was our primary end point and would not be affected by this. Fifth, length of followup is a possible limitation of our results. Late complications of hemiarthroplasty such as acetabular erosion and femoral component loosening can take years to develop [3, 46] and may not have been captured in our study. Although longer followup could have increased the detection of these complications, Parker et al. [38] reported very few reoperations after 3 years with minimum followup of 9 years. Finally, we did not analyze cognitive status or function. Cognitive status may affect how well a patient tolerates recovery, which could affect the reoperation rate [9, 22]. A patient’s functional status influences the risk of certain complications such as periprosthetic fracture and acetabular wear leading to reoperation. A measure of functional status also would help to determine the impact of treatment on quality of life [5, 18, 31, 44, 51]. Cognition and functional status could not be adequately assessed retrospectively. However, the large sample size in this study helped to offset the absence of these variables. The data in this study are the result of many patients being treated by 20 senior staff surgeons. Although approach and implant remained constant, it is likely small variations in technique did exist offering real-world applicability to our outcomes.

Bearing in mind these limitations, our data support the use of hemiarthroplasty in the treatment of displaced FNFs. Treatment with internal fixation and fracture displacement was independently associated with increased rates of reoperation, and displaced fractures treated with internal fixation were more likely to undergo reoperation. Our reoperation rates for displaced fractures of 38.1% and 6.6% in internal fixation and hemiarthroplasty, respectively, are within the range reported in the literature (Table 6). In a study by Parker et al. [39], reoperation rates were 6.6% for hemiarthroplasty versus 38.1% for internal fixation. We found the same reoperation rates for hemiarthroplasty and internal fixation. The reoperation rate for patients with nondisplaced fractures treated with internal fixation was 15.1% in our study with 45 months followup. This was within the range reported by others (Table 7). Although our rate was much higher than the 11.7% reoperation rate reported by Conn and Parker [13], it was corroborated in the study by Bjorgul and Reikeras [7]. This could be partially attributable to the greater than 90% followup at 1 year, our large sample size, and long-term followup. Furthermore, our study is retrospective, and therefore we would expect an actual failure rate to be even higher than our findings.

Table 6.

Comparison of studies of reoperation rates for displaced fractures

| Study | Study type | Followup (months) | Intervention | Hemiarthroplasty | Internal fixation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemiarthroplasty | Internal fixation | Reoperations/total | Total reoperation rate (%) | Reoperation/total | Total reoperation rate (%) | |||

| Frihagen et al. [18] | RCT | 24 | Bipolar cemented lateral approach | 2 cancellous screws | 11 of 108 | 10.2 | 47 of 111 | 42.4 |

| Parker and Gurusamy [37] | RCT | 24 | Uncemented Austin Moore | 3 AO screws | 15 of 229 | 6.6 | 86 of 226 | 38.1 |

| Davison et al. [14] | RCT | 60 | Thompson HA or cemented bipolar | AMBI compression screw and two-hole plate | 6 of 187 | 3.2 | 28 of 93 | 30.1 |

| Bjorgul and Reikeras [6] | Prospective | 72 | Exeter cemented HA | Olmed screws | 9 of 455 | 2 | 54 of 228 | 23.7 |

| Blomfeldt et al. [8] | RCT | 24 | Uncemented Austin Moore | 2 cancellous screws | 1 of 30 | 3.3 | 10 of 30 | 33.3 |

| Roden et al. [44] | RCT | 60 | Varikopf bipolar HA | 2 von Bahr screws | 8 of 47 | 17 | 34 of 53 | 64.2 |

| Soreide et al. [47] | RCT | 12 | Christiansen bipolar HA | von Bahr screws | 5 of 53 | 9.4 | 9 of 51 | 17.6 |

| Svenningsen et al. [50] | RCT | 36 | Christiansen bipolar HA (cementation unknown) | Compression screw versus McLaughlin nail plate | 8 of 59 | 13.6 | 16 of 110 | 14.5 |

| van Vugt et al. [54] | RCT | 36 | Cemented bipolar HA | Dynamic hip screw | 7 of 22 | 31.8 | 6 of 21 | 28.6 |

| van Dortmont et al. [53] | RCT | 24 | Thompson cemented unipolar HA | 3 AO screws | 1 of 29 | 3.4 | 4 of 31 | 12.9 |

| Puolakka et al. [42] | RCT | 24 | Thompson cemented unipolar HA | Ullevaal screws | 1 of 15 | 6.7 | 7 of 16 | 43.75 |

| Current study | Retrospective | 45 | Cemented bipolar HA | 3 cancellous screws | 44 of 667 | 6.6 | 129 of 339 | 38.1 |

RCT = randomized controlled trial; HA = hemiarthroplasty.

Table 7.

Comparison of current and published studies, nondisplaced

| Study | Study type | Followup (months) | Internal fixation | Total cases | Reoperations | Avascular necrosis | Nonunion | Periprosthetic fracture | Superficial infection | Deep infection | Other | Total reoperation rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lagerby et al. [31] | RCT | 12 | Richards or Uppsala screws | 75 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.7 |

| Phillips and Christie [40] | Prospective | 41 | Watson-Jones nail | 72 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9.7 |

| Gjertsen et al. [22] | Prospective | 12 | Olmed screws, Hansson pins, cancellous screws | 4310 | 436 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.1 |

| Hui et al. [25] | Prospective | 6 | Sliding hip screw | 29 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 31 |

| Chen et al. [11] | Prospective | 6 | Cancellous screws | 37 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16.2 |

| Bjorgul and Reikeras [7] | RCT | 38 | 2 Olmed screws | 225 | 42 | 10 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 18.7 |

| Conn and Parker [13] | Prospective | 15 | 3 cancellous screws | 375 | 45 | 15 | 24 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 11.7 |

| Doran et al. [15] | RCT | 29 | 2 hook pins | 58 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10.4 |

| Barnes et al. [4] | Prospective | 36 | Crossed screws, Smith-Petersen nail, or nail plate | 295 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.1 |

| Current study | Retrospective | 45 | 3 cancellous screws | 358 | 54 | 9 | 20 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 15.1 |

Categories marked with 0 were either stated as 0 or not reported; the definition of early loss of reduction was variable in each report. Some included this type of failure as nonunion; RCT = randomized controlled trial.

Most reoperations occurred within 1 year and 3 months for the fixation and hemiarthroplasty groups, respectively. Most failures after fixation were attributable to late complications such as nonunion and avascular necrosis. Greater than half of the reoperations after hemiarthroplasty, in contrast, are the result of a short-term complication, infection. Reoperation more than 3 years from the primary surgery occurred in seven of 697 patients (1.0%) after fixation and four of 667 patients (0.5%) after hemiarthroplasty supporting prior reports of relatively few long-term complications of these procedures [39, 45].

Our nonunion reoperation rates of 5.6% and 18.3% for nondisplaced and displaced fractures, respectively, treated with internal fixation, were in keeping with those reported in the literature (Table 8). Rates of reoperation secondary to avascular necrosis in our patient population were 2.5% and 5.6% for nondisplaced and displaced fractures, respectively. These rates are also consistent with rates in prior reports (Table 8). Ten percent of the nondisplaced group and 30% of the displaced group underwent a moderate reoperation (Table 5). This challenges the view that reoperations of failed fixation procedures are minor. Fixation failures may be explained by an elderly patient’s bone quality, disruption of vascular supply, and inherent instability of displaced fractures [12, 40]. A total of 6.6% of displaced fractures treated with hemiarthroplasty underwent reoperation; deep infection (3.4%) was the leading cause. Our infection rate is within previously reported rates ranging from 0% to 18% reported by Bhandari et al. in their meta-analysis [5]. Absent from our list of complications leading to reoperation is acetabular erosion. Haidukewych et al. [24] reported similar results in a long-term survivorship study with one case of acetabular erosion in 212 hemiarthroplasties.

Table 8.

Comparison of studies of complications with displaced fractures

| Study | Treatment | Total/reoperation | Complications | Early loss of reduction | Prominent screws/screw protrusion | Dislocation | Component loosening | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVN | Nonunion | |||||||

| Frihagen et al. [18] | 2 cancellous screws | 111/47 | 6 | 40 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 0 |

| Bipolar cemented | 108/11 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Parker et al. [39] | 3 AO screws | 226/86 | 11 | 78 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Uncemented Austin Moore | 229/15 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | |

| Davison et al. [14] | AMBI compression hip screw and two-hole plate | 93/28 | 8 | 22 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thompson HA or cemented bipolar HA | 187/6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Bjorgul and Reikeras [6] | Olmed screws | 228/54 | 8 | 35 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Exeter cemented HA | 455/9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | |

| Blomfeldt et al. [10] | 2 cancellous screws | 30/10 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Uncemented Austin Moore | 30/4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Roden et al. [44] | 2 von Bahr screws | 52/34 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Varikopf bipolar HA | 47/8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

| Soreide et al. [47] | von Bahr screws | 51/9 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Christiansen bipolar HA | 53/5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | |

| Svenning-sen et al. [50] | Compression screw or McLaughlin nail plate | 110/16 | 17 | 25 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Christiansen bipolar HA (cementation unknown) | 59/8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| van Vugt et al. [54] | Dynamic hip screw | 21/6 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cemented bipolar HA | 22/7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| van Dortmont et al. [53] | 3 AO screws | 31/4 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thompson cemented unipolar HA | 29/1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Puolakka et al. [42] | Ullevaal screws | 16/7 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thompson cemented unipolar HA | 15/1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Current study | 3 cancellous screws | 339/129 | 19 | 62 | 18 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| Cemented bipolar HA | 667/44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 | |

| Study | Acetabular erosion | Periprosthetic fracture | Hematoma | Superficial infection/wound dehiscence | Deep infection | Heterotopic ossification | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frihagen et al. [18] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 0 | |

| Parker et al. [39] | 0 | 6 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Davison et al. [14] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Bjorgul and Reikeras [6] | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Blomfeldt et al. [10] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Roden et al. [44] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | |

| Soreide et al. [47] | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Svenning-sen et al. [50] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| van Vugt et al. [54] | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| van Dortmont et al. [53] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Puolakka et al. [42] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Current study | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

AVN = avascular necrosis; HA = hemiarthroplasty; categories marked with 0 were either stated as 0 or not reported; the definition of early loss of reduction was variable in each report. Some included this type of failure as nonunion.

Increasing evidence supports the use of hemiarthroplasty over internal fixation in an elderly population with FNFs. Although hemiarthroplasty is not without its complications, the data indicate a lower failure rate with fewer reoperations, lower contralateral fractures, and overall lower costs with its implementation. Furthermore, our reoperation rate of 15.1% for nondisplaced fractures suggests that uncomplicated healing with treatment by fixation is not universal and that one of every seven patients can expect to undergo a second operation.

Acknowledgments

We thank John M. Hamilton BA, and Juhee Song PhD, for data accrual and statistical analysis of our manuscript, respectively.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Alolabi B, Bajammal S, Shirali J, Karanicolas PJ, Gafni A, Bhandari M. Treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly: a cost-benefit analysis. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23:442–446. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31817614dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angelini M, McKee MD, Waddell JP, Haidukewych G, Schemitsch EH. Salvage of failed hip fracture fixation. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23:471–478. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181acfc8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker RP, Squires B, Gargan MF, Bannister GC. Total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty in mobile independent patients with a displaced intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck: a randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2583–2589. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes R, Brown JT, Garden RS, Nicoll EA. Subcapital fractures of the femur: a prospective review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58:2–24. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.58B1.1270491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Swiontkowski MF, Tornetta P, 3rd, Obremskey W, Koval KJ, Nork S, Sprague S, Schemitsch EH, Guyatt GH. Internal fixation compared with arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the femoral neck: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1673–1681. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjorgul K, Reikeras O. Hemiarthroplasty in worst cases is better than internal fixation in best cases of displaced femoral neck fractures: a prospective study of 683 patients treated with hemiarthroplasty or internal fixation. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:368–374. doi: 10.1080/17453670610046271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjorgul K, Reikeras O. Outcome of undisplaced and moderately displaced femoral neck fractures. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:498–504. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blomfeldt R, Törnkvist H, Eriksson K, Söderqvist A, Ponzer S, Tidermark J. A randomised controlled trial comparing bipolar hemiarthroplasty with total hip replacement for displaced intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:160–165. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B2.18576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blomfeldt R, Tornkvist H, Ponzer S, Soderqvist A, Tidermark J. Internal fixation versus hemiarthroplasty for displaced fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients with severe cognitive impairment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:523–529. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blomfeldt R, Tornkvist H, Ponzer S, Soderqvist A, Tidermark J. Comparison of internal fixation with total hip replacement for displaced femoral neck fractures: randomized, controlled trial performed at four years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1680–1688. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen WC, Yu SW, Tseng IC, Su JY, Tu YK, Chen WJ. Treatment of undisplaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly. J Trauma. 2005;58:1035–1039; discussion 1039. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Chiu FY, Lo WH. Undisplaced femoral neck fracture in the elderly. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1996;115:90–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00573448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conn KS, Parker MJ. Undisplaced intracapsular hip fractures: results of internal fixation in 375 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;421:249–254. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000119459.00792.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davison JN, Calder SJ, Anderson GH, Ward G, Jagger C, Harper WM, Gregg PJ. Treatment for displaced intracapsular fracture of the proximal femur: a prospective, randomised trial in patients aged 65 to 79 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:206–212. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B2.11128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doran A, Emery RJ, Rushton N, Thomas TL. Hook-pin fixation of subcapital fractures of the femur: an atraumatic procedure? Injury. 1989;20:368–370. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(89)90017-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estrada LS, Volgas DA, Stannard JP, Alonso JE. Fixation failure in femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;399:110–118. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200206000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frandsen PA, Anderson E, Madsen F, Skjodt T. Garden’s classification of femoral neck fractures: an assessment of inter-observer variation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:588–590. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B4.3403602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frihagen F, Nordsletten L, Madsen JE. Hemiarthroplasty or internal fixation for intracapsular displaced femoral neck fractures: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335:1251–1254. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39399.456551.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao H, Liu Z, Xing D, Gong M. Which is the best alternative for displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly? A meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:1782–1791. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2250-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garden RS. Low-angle fixation in fractures of the femoral neck. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43:647–663. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gjertsen JE, Fevang JM, Matre K, Vinje T, Engesaeter LB. Clinical outcome after undisplaced femoral neck fractures. Acta Orthop. 2011;82:268–274. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.588857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gjertsen JE, Vinje T, Engesaeter LB, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Furnes O, Fevang JM. Internal screw fixation compared with bipolar hemiarthroplasty for treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:619–628. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haidukewych GJ, Berry DJ. Salvage of failed treatment of hip fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:101–109. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haidukewych GJ, Israel TA, Berry DJ. Long-term survivorship of cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty for fracture of the femoral neck. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;403:118–126. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200210000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hui AC, Anderson GH, Choudhry R, Boyle J, Gregg PJ. Internal fixation or hemiarthroplasty for undisplaced fractures of the femoral neck in octogenarians. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76:891–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iorio R, Healy WL, Lemos DW, Appleby D, Lucchesi CA, Saleh KJ. Displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly: outcomes and cost effectiveness. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;383:229–242. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200102000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain NB, Losina E, Ward DM, Harris MB, Katz JN. Trends in surgical management of femoral neck fractures in the United States. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:3116–3122. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0392-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kannus P, Parkkari J, Sievänen H, Heinonen A, Vuori I, Jävinen M. Epidemiology of hip fractures. Bone. 1996;18(Suppl):57S–63S. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kauffman JI, Simon JA, Kummer FJ, Pearlman CJ, Zuckerman JD, Koval KJ. Internal fixation of femoral neck fractures with posterior comminution: a biomechanical study. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13:155–159. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keating J. Femoral neck fractures. In: Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown CM, Tornetta P, editors. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. pp. 1561–1596. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lagerby M, Asplund S, Ringqvist I. Cannulated screws for fixation of femoral neck fractures: no difference between Uppsala screws and Richards screws in a randomized prospective study of 268 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:387–391. doi: 10.3109/17453679808999052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu-Yao GL, Keller RB, Littenberg B, Wennberg JE. Outcomes after displaced fractures of the femoral neck: a meta-analysis of one hundred and six published reports. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:15–25. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, Broderick JS, Creevey W, DeCoster TA, Prokuski L, Sirkin MS, Ziran B, Henley B, Audigé L. Fracture and dislocation compendium—2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(Suppl):S1–S133. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200711101-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyamoto RG, Kaplan KM, Levine BR, Egol KA, Zuckerman JD. Surgical management of hip fractures: an evidence-based review of the literature. I: femoral neck fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:596–607. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200810000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozturkmen Y, Karamehmetoğlu M, Azboy I, Açikgöz I, Caniklioğlu M. [Comparison of primary arthroplasty with early salvage arthroplasty after failed internal fixation for displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients] [in Turkish] Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2006;40:291–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker MJ. Garden grading of intracapsular fractures: meaningful or misleading? Injury. 1993;24:241–242. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(93)90177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parker MJ, Gurusamy K. Internal fixation versus arthroplasty for intracapsular proximal femoral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD001708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Parker MJ, Khan RJ, Crawford J, Pryor GA. Hemiarthroplasty versus internal fixation for displaced intracapsular hip fractures in the elderly: a randomised trial of 455 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:1150–1155. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B8.13522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parker MJ, Pryor G, Gurusamy K. Hemiarthroplasty versus internal fixation for displaced intracapsular hip fractures: a long-term follow up of a randomised trial. Injury. 2010;41:370–373. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips JE, Christie J. Undisplaced fracture of the neck of the femur: results of treatment of 100 patients treated by single Watson-Jones nail fixation. Injury. 1988;19:93–96. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(88)90081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Probe R, Ward R. Internal fixation of femoral neck fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:565–571. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200609000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puolakka TJ, Laine HJ, Tarvainen T, Aho H. Thompson hemiarthroplasty is superior to Ullevaal screws in treating displaced femoral neck fractures in patients over 75 years: a prospective randomized study with two-year follow-up. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 2001;90:225–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ravikumar KJ, Marsh G. Internal fixation versus hemiarthroplasty versus total hip arthroplasty for displaced subcapital fractures of femur: 13 year results of a prospective randomised study. Injury. 2000;31:793–797. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(00)00125-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roden M, Schon M, Fredin H. Treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures: a randomized minimum 5-year follow-up study of screws and bipolar hemiprostheses in 100 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:42–44. doi: 10.1080/00016470310013635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rogmark C, Carlsson A, Johnell O, Sernbo I. A prospective randomised trial of internal fixation versus arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the neck of the femur: functional outcome for 450 patients at two years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:183–188. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B2.11923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rogmark C, Flensburg L, Fredin H. Undisplaced femoral neck fractures: no problems? A consecutive study of 224 patients treated with internal fixation. Injury. 2009;40:274–276. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soreide O, Molster A, Raugstad TS. Internal fixation versus primary prosthetic replacement in acute femoral neck fractures: a prospective, randomized clinical study. Br J Surg. 1979;66:56–60. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800660118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Souder CD, Brennan ML, Brennan KL, Song J, Williams J, Chaput C. The rate of contralateral proximal femoral fracture following closed reduction and percutaneous pinning compared with arthroplasty for the treatment of femoral neck fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:418–425. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stromqvist B, Hansson LI, Nilsson LT, Thorngren KG. Hook pin fixation in femoral neck fractures: a two-year follow-up study of 300 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;218:58–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Svenningsen S, Benum P, Nesse O, Furset OI. [Femoral neck fractures in the elderly: a comparison of 3 treatment methods] [in Norwegian] Nord Med. 1985;100:256–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tidermark J, Ponzer S, Svensson O, Söderqvist A, Törnkvist H. Internal fixation compared with total hip replacement for displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly: a randomised, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:380–388. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.85B3.13609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tidermark J, Zethraeus N, Svensson O, Tornkvist H, Ponzer S. Quality of life related to fracture displacement among elderly patients with femoral neck fractures treated with internal fixation. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16:34–38. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Dortmont LM, Douw CM, van Breukelen AM, Laurens DR, Mulder PG, Wereldsma JC, van Vugt AB. Cannulated screws versus hemiarthroplasty for displaced intracapsular femoral neck fractures in demented patients. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 2000;89:132–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Vugt AB, Oosterwijk WM, Goris RJ. Osteosynthesis versus endoprosthesis in the treatment of unstable intracapsular hip fractures in the elderly: a randomised clinical trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1993;113:39–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00440593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zlowodzki M, Bhandari M, Keel M, Hanson BP, Schemitsch E. Perception of Garden’s classification for femoral neck fractures: an international survey of 298 orthopaedic trauma surgeons. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125:503–505. doi: 10.1007/s00402-005-0022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]