Abstract

Polyacrylamide hydrogels can be used as chemically and physically defined substrates for bacterial cell culture, and enable studies of the influence of surfaces on cell growth and behaviour.

Since its introduction by Robert Koch in 1882,1, 2 agar has been the most commonly used substrate for the growth and study of bacteria. Agar consists of alternating blocks of D-galactose and 3,6-anhydro-L-galactose and is a polysaccharide with a variety of characteristics that are useful for culturing bacteria: 1) it is biocompatible; 2) it is inert to metabolism and degradation by bacteria; 3) it remains gelled at the range of temperatures commonly used for bacterial culture; and 4) it forms a hydrogel with a large volume fraction of bound water that hydrates cells in contact with the polymer.3 Other classes of hydrogels, including gellan,4 alginate,5 xanthan gum,6 guar gum,7 and most recently Eladium™ 8 have been used as substrates for bacterial culture; however, they have not supplanted agar. These polymers share at least one shortcoming in common with agar for bacterial studies: chemical variability. The heterogeneity in the structure and the length of the polysaccharide chains of agar is influenced by the conditions for its isolation from marine algae.3, 9 The variability of agar makes it difficult to define and reproduce the chemical and physical properties of this hydrogel for bacterial studies.

Another disadvantage of agar for microbiological studies is the limited variability of surface chemistry that can be presented to cells. This characteristic is particularly important, as the chemistry of surfaces in contact with the outer cell wall influences bacterial physiology, behaviour, and growth.10-12 The chemical modification of agar is possible, but is not a widely used route for controlling the surface chemistry of this hydrogel.13-15 The introduction of classes of biocompatible synthetic polymers with defined chemical and physical properties for microbiological studies may transcend the limitations of agar and find applications in bacterial culture and cell biology.

Polyacrylamides (PAs) are a class of biocompatible hydrogels that have been instrumental in studying the influence of substrate stiffness on mammalian cell morphology.16-19 Importantly, the physical properties of PA—including, stiffness, porosity, and shear modulus—can be controlled during its synthesis.20 The most common approach to the synthesis of PA hydrogels is via the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide (1) in the presence of the cross-linker N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide (2) (Fig. 1). Different PA building blocks are commercially available, inexpensive, and enable control over the chemical and physical properties of PA (Fig. 1). Furthermore, several efficient approaches have been described for the synthesis of N-substituted acrylamide analogues that can be incorporated into PA hydrogels to introduce new surface chemistry.21 Another strategy for the synthesis of chemically diverse PA substrates is the copolymerization of 1 and 2 with acrylic acid or an acrylamide analogue containing a succinimidyl ester and the subsequent chemical modification of these moieties.22 Despite the ease of preparing PA substrates with defined chemical and physical properties, and a growing body of literature describing studies in mammalian cell biology, this hydrogel has been relatively unexplored for the study and culture of bacterial cells.23, 24

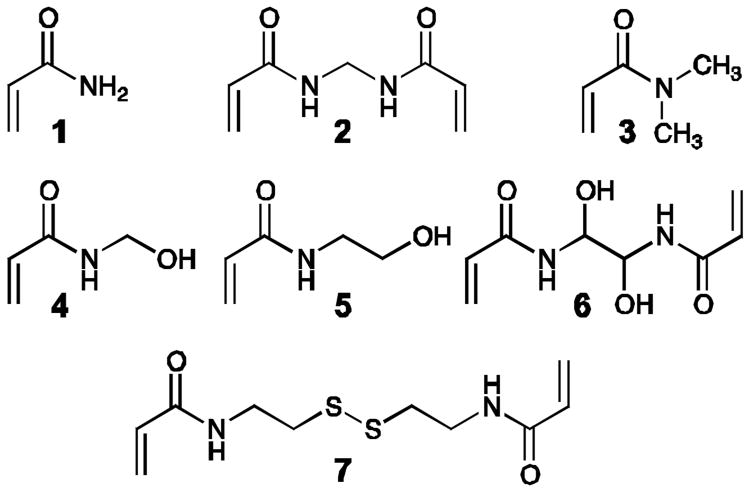

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of monomers (1, 3-5) and crosslinkers (2, 6-7).

In this manuscript we introduce and characterise PA hydrogels as a platform for the culture, study, and isolation of bacteria. We demonstrate the effects of surface chemistry and stiffness on bacterial cell growth and characterise growth rates. We demonstrate that PA chemistry affects community growth and spreading and discuss an approach for removing cells from substrates using reversible PA gels.

We observed that the free-radical polymerization of 1 and 2 produced polymers containing monomers and oligomers that were not incorporated into the polymer network and were toxic to bacteria.25 To remove these compounds, we incubated the gels in water prior to infusing them with liquid nutrient media (see Supplementary Information). Incorporating glutathione into the washing step aided in the neutralization of these toxic components.26

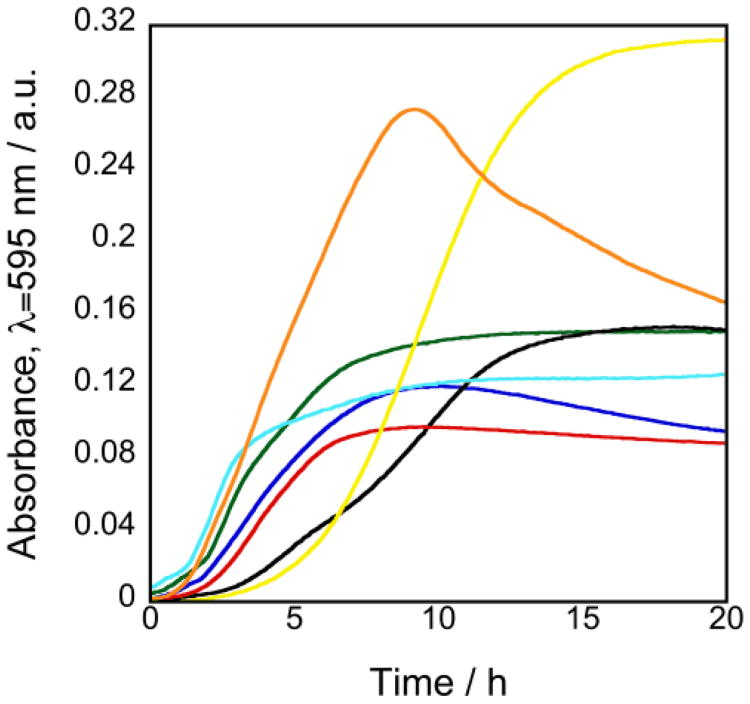

All of the strains we tested grew on PA gels consisting of 1 (1.0 M) and 2 (0.02 M) infused with liquid, including the Gram-negative bacteria Escherichia coli BW25113, Proteus mirabilis HI4320, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, and Serratia marcescens ATCC 274; and the Gram-positive bacteria Bacillus subtilis 168 and Staphylococcus epidermidis 3004 (Fig. 2). Other formulations of 1 and 2 also supported the growth of these strains (data not included). The growth of these bacteria on PA displayed three phases that are characteristic of the growth of bacteria in liquid culture and on agar surfaces: 1) lag phase; 2) exponential growth; and 3) stationary phase.

Fig. 2.

Growth of different bacterial strains on PA. PA hydrogels consisting of 1 (1.0 M) and 2 (0.02 M) were cast in the wells of a 24-well plate, and individual wells were inoculated with E. coli BW25113 (blue), P. mirabilis HI4320 (green), P. aeruginosa PAO1 (black), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (red), S. marcescens ATCC 274 (cyan), S. epidermidis 3004 (yellow), or B. subtilis 168 (orange) and incubated at 37 °C for 20 h. We measured the absorbance at λ=595 nm at 5 min intervals. The data indicates the mean absorbance value at each time point (n=4).

We measured the growth of E coli BW25113 on PA gels consisting of a range of different monomers and crosslinkers (1-7, Fig. 1) and observed small differences in growth rates (Table 1). Cell growth on gels consisting of a combination of crosslinker 2 with monomer analogues 3-5 was slower than with 1+2 (P<0.01). The growth of cells on gels consisting of a combination of 1 with crosslinkers 6 and 7 was similar to 1+2 (P>0.01). This observation indicates that alteration of the surface chemistry by changing the monomer can influence bacterial growth.

Table 1.

The growth rate of E. coli depends on the chemistry of the monomer.

| Gel Composition | 1+2 | 3+2 | 4+2 | 5+2 | 1+6 | 1+7 |

| Doubling Time (min) | 42 ± 4.5 | 48 ± 6.7 | 52 ± 5.2 | 53 ± 4.9 | 47 ± 4.4 | 43 ± 3.2 |

Agar substrates are significantly stiffer than PA gels. To explore whether substrate stiffness alters cell physiology by affecting cell growth, we compared the growth of cells of E. coli BW25113 on PA gels ranging in stiffness from 1.4 kPa (1, 0.5 M) to ∼50 kPa (1, 2.0 M). The doubling time did not change significantly with increasing acrylamide concentration (P>0.01; see Supplementary Information) or with increasing agar percentage (Fig. 3). However, the doubling time on agar was significantly lower than on PA; this difference likely arises from the difference in the rate of nutrient diffusion through the hydrogels (Fig. S2). PA hydrogels can be prepared with different combinations of chemistry and stiffness that will enable studies of mechanisms bacteria use to sense their physical environment.

Fig. 3.

Cell growth rate is independent of hydrogel stiffness. Open circles represent PA gels (from left to right, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 M 1; all 0.02 M 2), open squares represent agar (from left to right, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, and 2.5% w/v). The data indicates the mean doubling time ± S.D. (n=4).

Many bacteria use extracellular organelles and the secretion of biomolecules to tether themselves to surfaces prior to or during growth. The attachment of cells to surfaces during growth can prevent the collection and analysis of entire communities of cells from surfaces, particularly when cells form biofilms.11 Cell attachment can complicate the study of cell-surface interactions and the effects of surfaces on bacterial growth. To overcome irreversible attachment of cells to surfaces, we designed PA substrates that can be dissolved after bacterial growth. We synthesised reversible PA gels by polymerizing 1 with bis(acryloyl)cystamine (7), which contains a disulphide bond that can be reduced after cell growth. Similarly, hydrogels that incorporate N,N′-dihydroxyethylene bisacrylamide (6) as a crosslinker can be incorporated into PA hydrogels that dissolve upon treatment with sodium periodate.27

We synthesised PA hydrogels consisting of 1 (2.0 M) and 7 (0.02 M), infused the gel with nutrients, and cultured cells of E. coli BW25113 on the substrate surface. We released cells by dissolving the gel using tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP; 10 mM), collected the cells, and cultured them on 1.5% agar gels containing LB media to determine whether TCEP treatment affected their viability; nearly all of the cells were released and 100% of these were viable (see Supplementary Information). Importantly, this characteristic enables the collection of entire populations of cells growing on hydrogel surfaces for analysis and further experiments, and ensures that cells in contact with the substrate are retrieved and studied.

In this paper, we introduce PA substrates as an alternative to agar for microbial cell culture and studies. Over the last 130 years, agar has been the central material used for microbial culture and isolation. However, a lack of control over the chemical and physical properties of agar limits its application in probing the interactions between bacteria and surfaces. The addition of PA to the suite of microbiological techniques and materials for culturing and studying microorganisms can complement agar and other microbiological reagents. The chemically and physically defined features of PA may enable studies of microorganisms in conditions that more closely mimic their native environment.

It is widely recognised that the physical properties of the environment play a role in mammalian cell behaviour;16, 17 however, this connection was recognised only recently for bacteria.28, 29 For example, 10% of all genes in the S. enterica genome are differentially regulated between growth on 0.6%(w/v) and 1.5% (w/v) agar.30 Apparently subtle differences in the physical properties of polymers produce dramatic genetic differences, which influence the biochemistry of bacteria. New opportunities for manipulating the physical and chemical microenvironment of cells may play an important role in the study of bacterial-environmental interactions. Similar to agar, PA is inexpensive and is routinely prepared in biological laboratories for protein purification. A significant advantage of PA over agar is the ease and precision of control over the physical and chemical properties of hydrogels. There are several areas in which PA substrates need to be optimised for microbiology studies, including the incubation time required to remove the toxic unpolymerised monomers and oligomers. Two approaches to transcend this limitation include altering the polymerization conditions and adding a biologically compatible reagent that reacts with acrylamide via a Michael-type addition and renders it non-toxic.

We do not envision polyacrylamide as a replacement for agar for the routine culturing of laboratory strains; instead we see it as a step toward the introduction of new classes of polymers for microbiological studies. The use of PA opens up opportunities for studying the relationship between bacterial cells and their environment, as well as the study of microorganisms that have previously been thought to be unculturable in the laboratory. Interfacing PA substrates for cell culture with methods for controlling the spatial organization of cells on surfaces may open new doors in the study and engineering of microbes and their communities.31-35

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by USDA, DARPA, March of Dimes Foundation (5-FY10-483), and the Alfred P. Sloan Research Foundation. We thank Max Salick and Wendy Crone for assistance with tensile testing measurements. HHT was supported by a NIH Molecular Biosciences Training Grant (T32 GM07215), and LDR was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Detailed experimental procedures and additional doubling time data. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

References

- 1.Hitchens AP, Leikind MC. Journal of Bacteriology. 1939;37:485–493. doi: 10.1128/jb.37.5.485-493.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koch R. Review of Infectious Diseases. 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armisen R, Galatas F, Phillips G, Williams P. Handbook of hydrocolloids. 2009:82–107. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shungu D, Valiant M, Tutlane V, Weinberg E, Weissberger B, Koupal L, Gadebusch H, Stapley E. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1983;46:840–845. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.4.840-845.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Augst AD, Kong HJ, Mooney DJ. Macromolecular Bioscience. 2006;6:623–633. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200600069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babbar SB, Jain R. Current Microbiology. 2006;52:287–292. doi: 10.1007/s00284-005-0225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain R, Anjaiah V, Babbar SB. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2005;41:345–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2005.01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gognies S, Belarbi A. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2010;88:1095–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2800-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira-Pacheco F, Robledo D, Rodríguez-Carvajal L, Freile-Pelegrín Y. Bioresource Technology. 2007;98:1278–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Copeland MF, Weibel DB. Soft Matter. 2009;5:1174–1187. doi: 10.1039/B812146J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renner LD, Weibel DB. MRS Bulletin. 2011;36:347–355. doi: 10.1557/mrs.2011.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strahl H, Hamoen LW. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 2010; pp. 12281–12286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hearn MT. Methods in Enzymology. 1987;135:102–117. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)35068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo Y, Shoichet MS. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:2315–2323. doi: 10.1021/bm0495811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miron T, Wilchek M. Methods in enzymology. 1987;135:84–90. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)35066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang YL. Science. 2005;310:1139–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engler A, Bacakova L, Newman C, Hategan A, Griffin M, Discher D. Biophys J. 2004;86:617–628. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engler AJ, Richert L, Wong JY, Picart C, Discher DE. Surface Science. 2004;570:142–154. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rehfeldt F, Engler AJ, Eckhardt A, Ahmed F, Discher DE. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2007;59:1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker B, Murff R. Polymer. 2010;51:2207–2214. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lele B, Kulkarni M. US Patent 6,369. 2002;249

- 22.Brandley BK, Weisz OA, Schnaar RL. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262:6431–6437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodin VB, Bulatova RF, Domotenko LV, Inkovskaya TE, Artyukhin VI. Prikladnaia Biokhimiia i Mikrobiologiia. 1992;28:623–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tiesler E, Seah KC. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie, Parasitenkunde, Infektionskrankheiten und Hygiene 1 Abt, Originale. 1973;224:247–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Starostina N, Lusta K, Fikhte B. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 1983;18:264–270. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tong GC, Cornwell WK, Means GE. Toxicology Letters. 2004;147:127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Connell PB, Brady CJ. Analytical Biochemistry. 1976;76:63–73. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90264-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harshey RM, Matsuyama T. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 1994; pp. 8631–8635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lichter JA, Thompson MT, Delgadillo M, Nishikawa T, Rubner MF, Van Vliet KJ. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:1571–1578. doi: 10.1021/bm701430y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Q, Frye JG, McClelland M, Harshey RM. Molecular Microbiology. 2004;52:169–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ingham C, Bomer J, Sprenkels A, van den Berg A, de Vos W, van Hylckama Vlieg J. Lab on a Chip. 2010;10:1410–1416. doi: 10.1039/b925796a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ingham CJ, Sprenkels A, Bomer J, Molenaar D, van den Berg A, van Hylckama Vlieg JET, de Vos WM. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 2007; pp. 18217–18222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim HJ, Boedicker JQ, Choi JW, Ismagilov RF. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 2008; pp. 18188–18193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weibel DB, Lee A, Mayer M, Brady SF, Bruzewicz D, Yang J, DiLuzio WR, Clardy J, Whitesides GM. Langmuir. 2005;21:6436–6442. doi: 10.1021/la047173c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu L, Robert L, Ouyang Q, Taddei F, Chen Y, Lindner AB, Baigl D. Nano Letters. 2007;7:2068–2072. doi: 10.1021/nl070983z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.